**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Material” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. Find it in Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You (1974), republished in A Wilderness Station: Selected Stories 1968-1994, or in Selected Stories (1996).

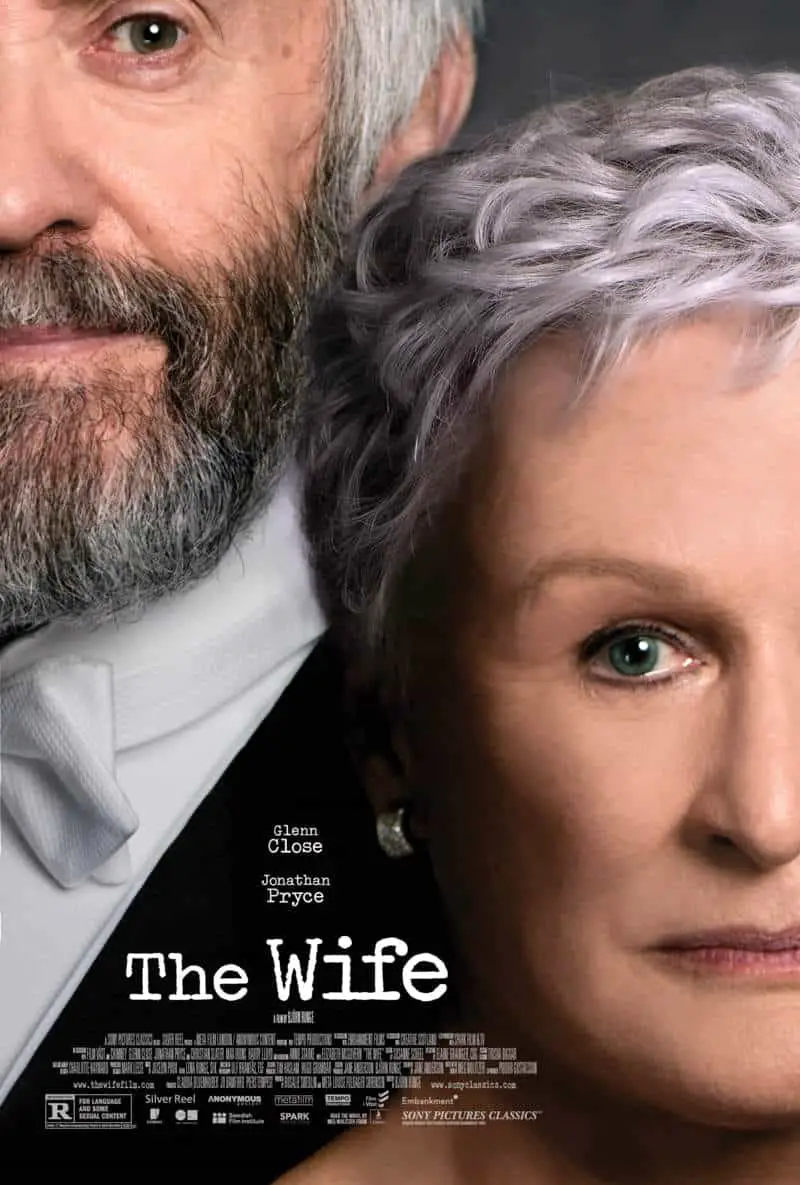

Alice Munro investigated the topic of gender and fiction writing in “The Office“. In that earlier piece, a middle-class mother with a burning desire to write hires an office space in town. She hopes to remove herself from home duties for dedicated thinking and writing time. However, the middle-aged male landlord won’t give her any peace and quiet, feeling himself entitled to her time and attention. I liken that short story to Meg Wolitzer’s novel The Wife. (There’s also a 2017 film adaptation.)

Below is the sadly familiar story of a (real world) woman writer whose jealous husband can’t deal with her success:

Before we were a couple, my husband and I became friends in a creative writing workshop at university. I think that fact communicates some of the tension in our marriage, particularly in the last years. I was working as a writer and editor; he was working as an attorney. When I got good news related to my writing – a publication, a grant, an invitation – I sensed him wince inwardly. So I stopped sharing good news. I made myself small, folded myself up origami tight. I cancelled or declined upcoming events: See, I’ll do anything to make this marriage work.

When poet Maggie Smith’s Good Bones went viral, it helped to expose a faultline at the centre of her marriage. What happened when the true dynamic of her relationship was revealed? by Australian author Maggie Smith

Now to Alice Munro’s short story. “Material” comes at the topic of gender and writing from a different angle from the examples listed above.

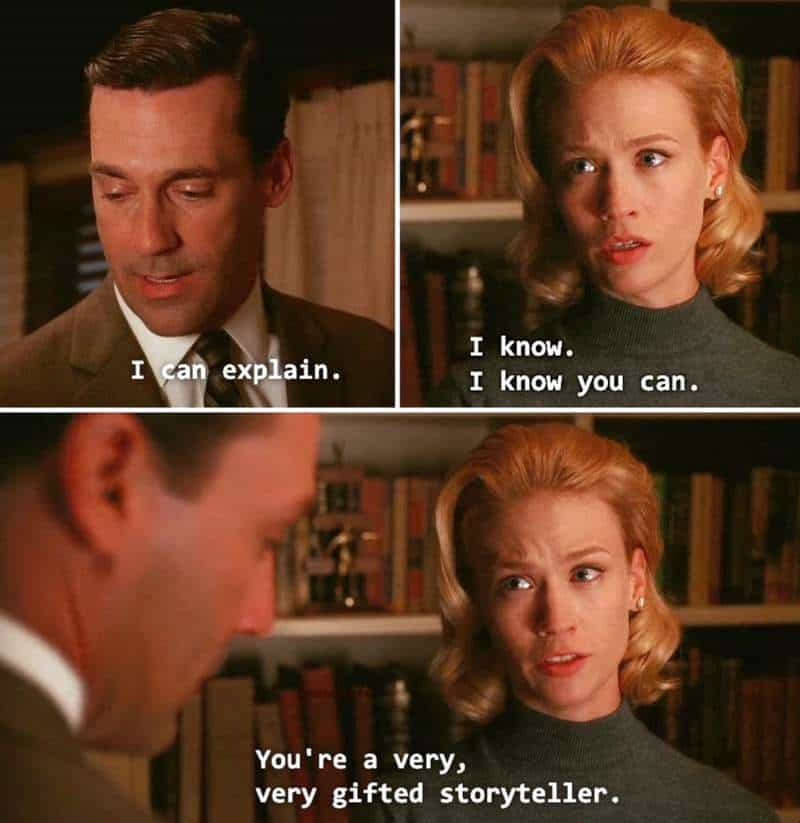

In this narrative, the (ex-)wife of a male author harbours absolutely no literary aspirations of her own (despite just having written a story of Alice Munro quality, ha). Instead, she is relegated to the place of a helpmate, running her life around his. Through proximity and familiarity, she learns that whatever writerly glamour makes him attractive to the (largely female) reading public as a writer evaporates in the domestic sphere.

Later, as his ex wife, she understands very well, at close range, that his public persona is little more than a careful construction. In a way she admires him for this. Another part of her is angry about it the privilege and sway that he has, especially over women.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “MATERIAL”?

It’s fun to run an AITA on this one. (“Am I The A$$hole”?: A subreddit phenomenon.)

AITA for letting my husband turn off the basement pump so he could get some sleep, knowing full well our neighbour’s house might flood?

Edited to add: The pump was turned off not just because of the noise. It’s expensive to run, and we spend a goodly proportion of our household income on keeping it going, even though it’s not our upstairs residence that would ever be flooded.

First time writing. I am not the writer; my husband is the writer of the house.

Myself 27(F) and my husband 29(M) live in Vancouver. We are currently pregnant with our first child.

The landlord’s daughter lives in the basement of our rented house. We call her ‘the harlot’, but only ironically. I’ve no idea why we settled on that word. We mean it in a classy way. Let’s call her ‘Dotty’. Dotty is a fitting name, almost symbolic.

She’s been married before, husband left her. Health isn’t great. And let me tell you, I hear all about it. This woman is a massive oversharer. It’s true she’s had a bad run with illnesses, miscarriages and whatnot, but I even know the heaviness of her monthly flow. God knows why she tells me such things. Hoping to find a friend in the woman upstairs, perhaps?

Dotty’s not the nicest woman to look at. She looks like a bag woman who takes buses. In fact she does ride buses.

At first we drank tea together, than progressed to beer. I enjoy going down to the basement because when I am with my husband — who is a writer — I get to tell him stories of my own, with Dotty as material. This evens the balance sheet a bit between us, since he’s the one who fancies himself a writer, and to be fair, he is one. I gave it up long ago, even though we met through a writing group.

Anyway, I’m pretty sure Dotty is, indeed, a harlot. She has gentleman visitors in the middle of the day, when I’ll catch her tipsy and in her night-wear. My husband has read about harlots in books, and they tend to look just as frumpy as Dotty does.

We sometimes overhear Dotty singing and playing piano, badly. We stop what we’re doing and listen, for the entertainment value. I don’t suppose Dotty and I can ever really be friends. We just happen to be sharing the same building.

My husband is a writer. He’s a very intelligent man and requires absolute silence to write. He refuses to tell Dotty to stop the music, and requires me to do it, because apparently I encourage her. Sometimes he’s in a great mood, though. I have no bearing on his moods — it all depends on how his writing is going. Sometimes I do wonder if he loves me as much as he loves his play-in-progress.

At certain times of the year we get a lot of melting in our street. This requires a pump to run all night, to keep the basement from flooding. Unfortunately, due to my husband’s sensitivity to noise, he is unable to get a good night’s rest when that pump is going. Then the lack of sleep impacts his ability to work the next day.

So he turned it off, and then persuaded me to keep it off. I was very reluctant, knowing full well that the melting snow might flood Dotty’s residence. But then again, there was a chance she’d be fine down there?

However, Dotty’s place did flood, and all because Hugo turned that pump off. But Dotty is too simple to realise it was our fault. She’s used to bad things happening to her, and is quite fatalistic about the whole thing.

I suppose it is fate. I mean, I never asked to be married to a man with such noise sensitivity, and Hugo never asked for his noise sensitivity either. That pump really was irritating him. Nor were we to know that the basement would definitely flood if we turned off the pump. If we knew for sure that would happen, we surely wouldn’t have done it.

Anyway, I’ve never tampered with the pump myself, and I’d have had to work out how to turn it back on in the dead of night, in a rain storm. Also, my husband told me I was being ‘alarmist’, and I supposed I believed him. I can overreact sometimes. He steadies me in that way husbands so often do.

AITA for letting that pump stay turned off, and for letting the harlot-in-residence think the flooding was an act of God? I sort of realise now that the pump should have been kept going, but do I really owe Dotty the full story? Isn’t she better off thinking the flooding of her residence is no one’s fault?

UPDATE: 17 Years Later.

I know this wasn’t my question, but Hugo and I did end up getting a divorce. It wasn’t directly because of this, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve realised how much women kowtow to men’s opinions. Gaslighting is an overused word, but what do we call it when our husbands tell us we’re overreacting when in fact we are simply being considerate and sensible?

Even when we know better, women — perhaps especially we white women — find it easier to just submit to our husbands in many small ways. Over the course of a life together, this wears on the soul. He never hit me, but he was a master of the big sulk.

As I said, that sulky, self-centred husband is my ex-husband now. He’s gone on to marry someone else. He had three children with her, then married someone else again. He had another three children with the latest wife. The older he gets, the younger his wives. The current one was his student. I didn’t realise then what I know now; that Hugo is a serial monogamist, and only likes the beginnings of things. The pattern was yet to be established. I suppose I can’t blame myself for falling for him, though you’d think the third wife would be wary.

The one daughter we had together is now 17. Hugo is no longer in either of our lives. But now and then we do see new fiction published and occasionally I take a peek. It was actually my current husband who placed his latest short story collection in my hands.

I no longer know who my daughter’s father is, as a person, but his published fiction offers strange insights. For instance, I recently read his latest piece and recognised the historical inspiration. He’s only gone and written a fictionalised version of Dotty from next door, recalled after all those years. He’s even got her facial expressions down pat. I can’t for the life of me work out how he’d have remembered such detail, because he never spoke to Dotty, not that I can remember. Did his picture of Dotty come entirely second-hand, from my descriptions of our times together?

Though now I really think about it, maybe he did see more of Dotty than I realised at the time. When he cautioned me to mind my own business, was he really The Bigger Person, or could it be that he was utilising Dotty’s services himself, on the sly? Oh, probably not. But I’ll never know, will I, because you can never really know a person. Not even when you’re married to him. Perhaps especially not then, because we tell ourselves stories about our partners, moulding them mentally into the people we wish them to be.

I’m remarried now to another man. This time I avoided marrying a writer. I’m with an engineer. This go around, I thought I was marrying someone completely different. After all, my current husband is from Romania, an entirely different country from myself and my first husband. But the older I get, the more I realise I’ve married basically the same person, in many ways. There must be something in me — or in the wider culture — pushing me towards such partnerships. Or perhaps the dominant culture conspires to push heterosexual partnerships in a general proscribed direction — a frustratingly common dynamic in which the man is the dominant partner, his wife playing second-fiddle.

Despite knowing many details, I never really knew my first husband and I’ll never entirely know this one, either. Sometimes I wonder who I’m looking at. Has my engineer husband really forgotten how to speak Romanian, or has he fabricated his entire back story? I have had these thoughts. They’re fleeting. People are both predictable and unknowable, a strange combination to live with. In some ways I have become my first husband in this new relationship — I get into my moods; my second husband knows to leave me alone.

We all have many selves, but I’ve made peace with that now. I decided not to send Hugo a letter, reconnecting after all these years about our shared bank of memories about ‘the harlot-in-residence’. At first I admired the story, and felt Dotty to be lucky to have been immortalised by a famous writer (who I thought would never make it). But when I sat down to write it, I became quite angry. As much as I admire the men in my life for making a go of things, it turns out I have this deep-seated, inchoate resentment which surfaces only occasionally.

RESONANCE OF “MATERIAL” BY ALICE MUNRO

THE CONSTRUCTED SELF

I believe this story construction (of two husbands, one from the past) allows Alice Munro to convey a more general idea about constructed personalities. Munro has taken the clear example of writers (an establishment she knows very well) to illuminate how we all have public constructions of ourselves, and different constructions which we show to our intimate partners. But the phenomenon applies to everyone. We don’t have to be a writer. There’s nothing special about writers in this regard. It’s simply most obvious in writers.

At one point, the narrator critiques her ex-husband’s bio. Any writer will be familiar with the slightly odd request in which they are required to provide an author bio, but in third person. I’ve had to do this myself at times and it’s weird. Here is Hugo’s bio from the 1970s. Note how closely it resembles a social media bio — in content if not in length:

Hugo Johnson was born and semi-educated in the bush, and in the mining and lumbering towns of Northern Ontario. He has worked as a lumberjack, beer-slinger, counter-man, telephone lineman and sawmill foreman, and has been sporadically affiliated with various academic communities. He lives now most of the time on the side of a mountain above Vancouver, with his wife and six children.

“Material” by Alice Munro

“With his wife and six children”. Hugo has an older child he doesn’t mention. Also not mentioned: That three of the children are by his second wife, and the eldest of the younger three was born before Hugo had finished his relationship with Mary Frances.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TITLE

Alice Munro wrote “Material” long before the age of the Internet, where every online person (that’s most of us) have a constructed persona which is “materially” different from our real-world persona. Plenty has been said about this elsewhere; this “falsity” inherent to nutshell social media biographies was the topic of cultural commentary for the first decade or so of this new millennium.

But people have stopped mentioning it so much now. Probably because we are so used to the notion that “real” life is not reflected by social media. In fact, the social media version probably isn’t even considered “false” anymore. It is simply expected that we show our “best selves” online. Why wouldn’t you? After all, whatever you put online stays there forever. We are all hustlers now, and our online lives inseparable from our off-line lives. We can all expect to be ‘researched’ — by potential friends and love interests, by employers, by customers. Our survival depends on curation.

So in one aspect, this 1970s short story is saying nothing new to contemporary readers. On the other hand, Munro has written a story with enduring resonance which speaks particularly to 21st century readers.

Here’s another story about a basement pump (the likes of which I am utterly unfamiliar, living as I do, in Australia).