We love stories about tricksters who get away with stuff. But we don’t want them to get away with stuff forever. We want them to be found out.

For instance, when Emerson Moser retired from Crayola and revealed that he is colour blind, he made sure that this one little detail of his career would eclipse all others. I’m not sure if this is what he intended, but that is his Internet legacy.

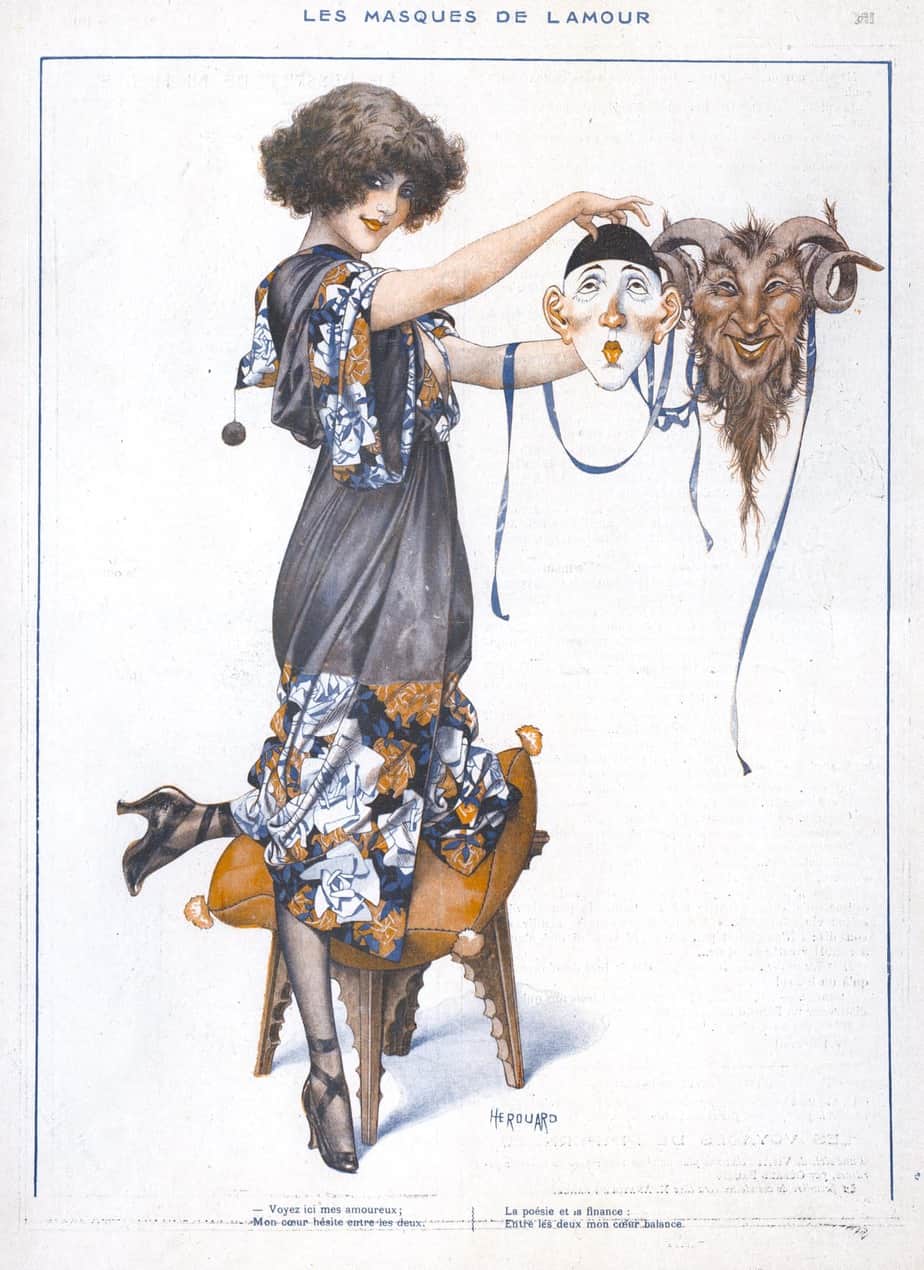

Audiences love masks. More specifically, we love the slipping of the mask. Our love for the mask may explain the wide appeal of celebrity gossip:

I’ve come to realize that my main attraction to celebrity gossip comes from a fascination with slipping facades. I don’t care what celebrities eat for breakfast or what they buy at Whole Foods, but I like it when they lose their shit: the Britney Spears breakdown, Lindsay Lohan’s downward spiral, Paris Hilton going to jail, etc. I’m sure part of it is just base, ugly schadenfreude on my part, but there’s something else too. Their public images are so carefully micromanaged and manipulated and wrapped in Teflon, and there’s something exhilarating about seeing the mask slip once they stop giving a shit.

Suzanne Riveca at The Short Form

There is an ever more acute difference — and an intolerableness — between my inner self, which I know is the real me, and various faces of the outside world.

from Patricia Highsmith’s diaries

No life, no matter how successful and exciting it might be, will make you happy if it is not really your life. And no life will make you miserable if it is genuinely your own.

Carol S. Pearson, Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World

When creating characters for fiction, storytellers sometimes draw a distinction between what Michael Hauge refers to as ‘identity’ (masks) and ‘essence’.

- Identity refers to the faces people present to the world, also known as masks.

- Essence is the (one) true self.

This distinction is more clear in some non-Western cultures, for example in Japan. Japanese culture draws a clear distinction between ‘omote’ and ‘ura’ (public face and private face). The words literally mean ‘front’ and ‘behind’.

We may not have widely understood words to describe this in English, but the distinction is clear in our history of storytelling. The underlying message of most stories is the same no matter the genre: It’s only when a mask (false identity) comes off that true happiness can be found.

(Interestingly, this is not how Japanese culture sees it. In Japan, the ‘omote’ face is a necessary ‘mask’ for a harmonious society.)

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.

Oscar Wilde

Lie to yourself about this and you will

Frank Bidart, “Queer”

forever lie about everything.

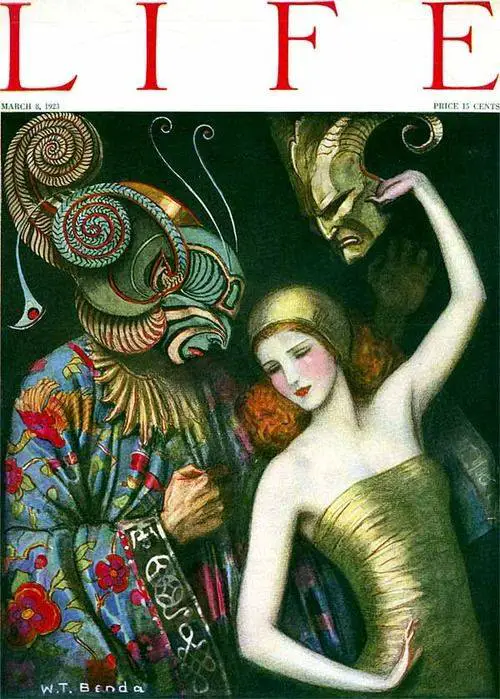

A Brief History of Masks

Like the veil, another aspect of costume worn in front of the face, the mask has a dualistic nature, and can indicate:

- The sacred

- The profane

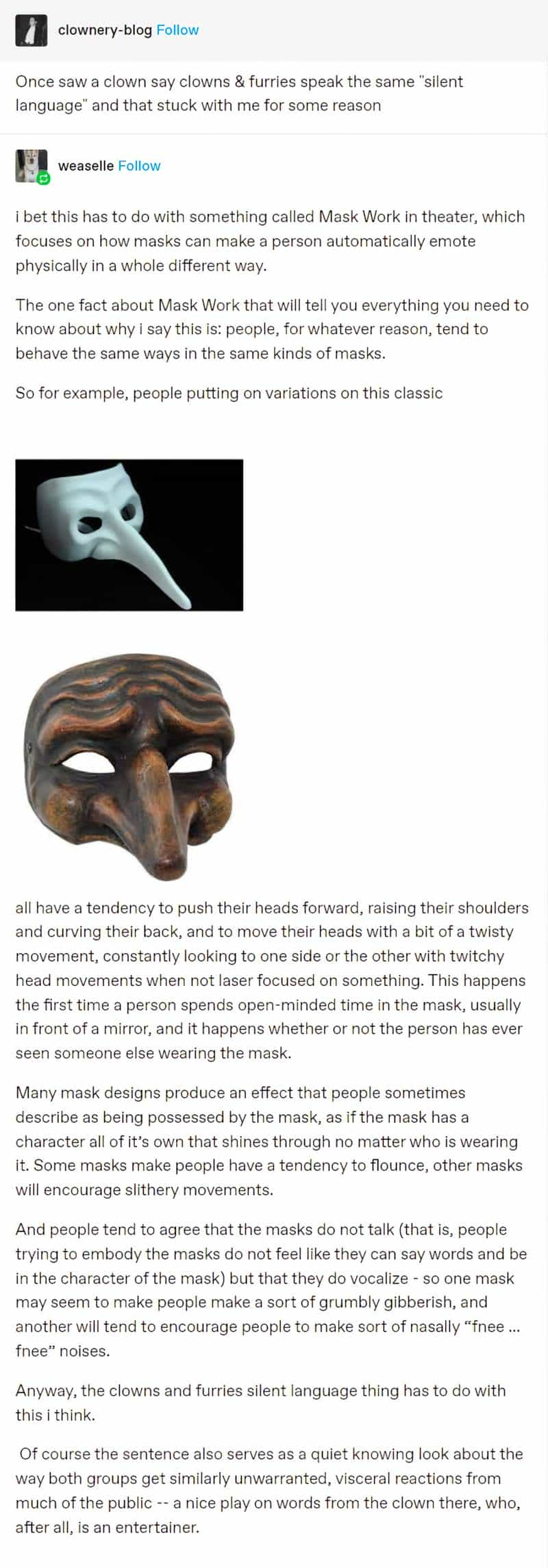

And both at the same time. This can be seen in a stock character such as the Harlequin, whose mask (alongside the diamond-patterned clothing) is an indispensable part of the costume.

Some think the word ‘mask’ comes from Arabic maskharat, which means clown.

Go back into antiquity and humans across cultures have used masks as a way to transform themselves, often as a way to try and become closer to the gods. (Maybe coming closer to the gods helps us come to terms with death?)

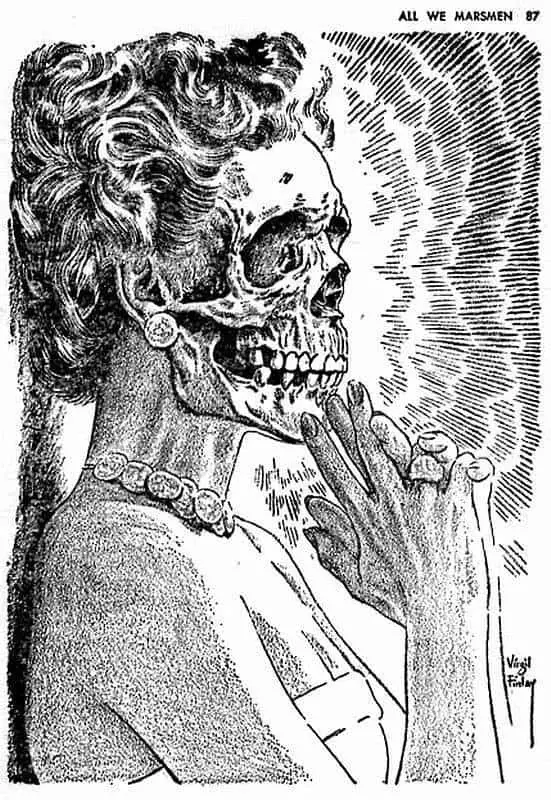

The Victorian fascination with death extended to the production of a range of Memento Mori, objects designed to remind the owner of the death of a loved one and indeed, their own eventual demise. These took several forms, locks of hair cut from the dead were arranged and worn in lockets, death masks were created and the images and symbols of death cropped up in all sorts of everyday paintings and sculptures. Photographs of dead relatives became an increasingly popular feature of family albums, often in a lifelike pose with a rosy colouring and even open eyes painted over eyelids.

Victorians and the Art of Dying

Faces are ‘masked’ in various ways:

- Sooted cheeks (Ancient Rome)

- Red noses (devils from the Middle Ages)

- Actual masks (in the Italian commedia dell’arte, see Harlequin)

- Bismuth and rouge (in the English version of commedia dell’arte)

- Flour (in old French farces)

- Burnt cork (in the ‘n*gger’-minstrel shows)

- Make up (at Shrovetide, a festival/carnival before Lent)

It’s hard to find a culture where there wasn’t some kind of mask wearing. Reasons for wearing masks vary:

- To embody spirit helpers

- As a haven for dead ancestors and animal spirits

- As a place for demons/gods

- In dance and mime, to exorcise evil spirits and other bad things

- To catch the soul of a living being (including plants), and then send it back to the spirit world, generally so that humans can keep benefitting from it

Masks and dance go hand in hand, probably because as Lommel said in 1991, ‘ceremonies demand ever-new creative impulses’.

It is a thousand pities never to say what one feels.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway

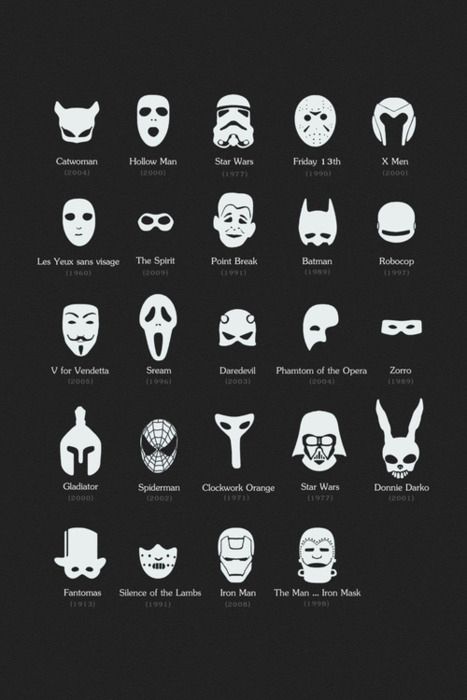

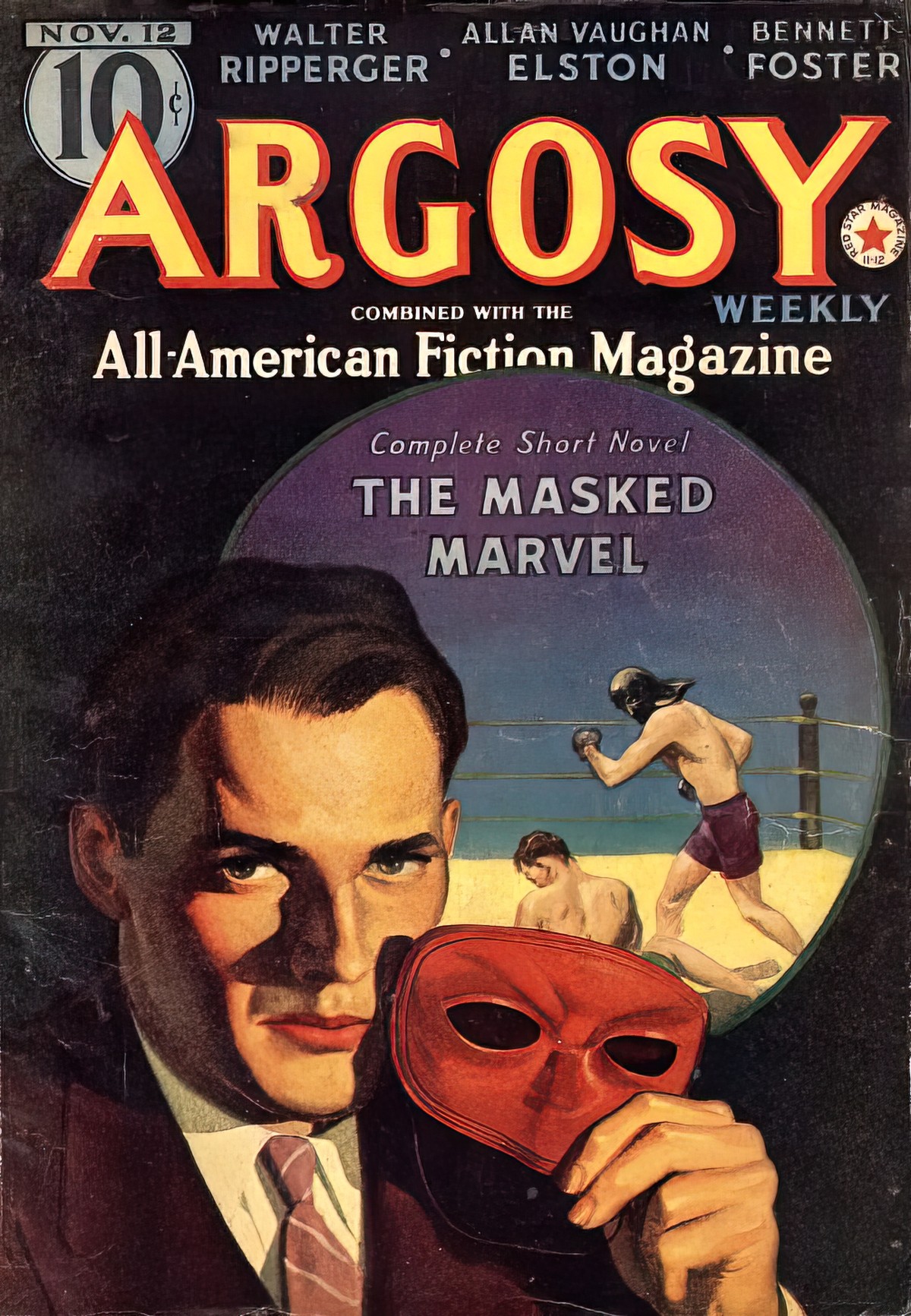

Modern Storytelling Genre And Masks

The ‘mask’ of modern storytelling no longer looks like an actual mask/rouge/red nose. The mask comes in many forms, and I mean it here to refer to any kind of deception or inauthenticity.

The Love Genre

This omote/ura distinction is important in the love genre. The audience is clued in about who is right for each other because even if the romantic pair start off fighting (fight fight, kiss kiss trope), they eventually get to know the other’s essence. All other romantic rivals never get past the ‘identity’ stage of knowing.

Comedies

The transgression comedy is all about masks. A character tries to get away with something by posing as somebody else. The audience is in superior position, waiting with glee for the mask to come off. When it does, this big scene is full of comedy. We’ve been anticipating it, so it’s especially satisfying.

Tootsie is the tentpole example of a transgression comedy. A man dresses as a woman because he’s ruined his reputation in Hollywood and needs work. (If he dresses as a woman he assumes a whole new identity.)

A lot of The I.T. Crowd episodes are transgression comedy. Jen Barber is the biggest fraud, having secured the job as head of I.T. by bluffing. It is soon revealed that this is part of her character in general, to the last detail. In a later episode she buys shoes that are too small because she wants people to believe she has dainty little feet. Roy is a little duplicitous but not smart about it. Jen’s duplicitous nature contrasts with the personality of Moss, who says exactly what’s on his mind and takes everything literally.

In the “Kicking Up A Stink” episode of Kath and Kim, Sharon has found a job as a bootcamp leader, but the mask comes off when she invites Kim along. Kim isn’t one bit scared of her and walks off, prompting a mass exodus, ruining Sharon’s session.

Thrillers

The transgression thriller — surprisingly, perhaps — has the same structure as a transgression comedy. It’s just the entire tone and plot details that are different.

By the way, the structure looks like this, courtesy of The Narrative Breakdown podcast:

Discontent – someone is unhappy about something

Transgression with a mask – peculiar to comedy and thrillers

Transgression without a mask – midpoint disaster when the mask is ripped off

Dealing with consequences

Spiritual Crisis – happens in almost every story

Growth Without a Mask

Another name for the transgression thriller is ‘the wrong man thriller’. Hitchcock was a big fan. He would set up a falsely accused innocent. Over the course of the story the truth is revealed.

Examples Of Wrong Man Thrillers:

- Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man

- North By Northwest

- In children’s literature: Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolf

- Modern indie film: I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore

Horror Stories

It is said that horror stories exist to define what is normal by showing us what isn’t. There’s a long tradition of horror monsters who act because ‘the devil made them do it’. Equally lazy but more modern: The horror monster is ‘psychotic’.

The horror genre is beginning to move more solidly into a phase where the audience discovers the ‘true identity’ of the monster and finds that in fact we are looking at the darkest parts of ourselves. This is widely known as The Shadow In The Hero.

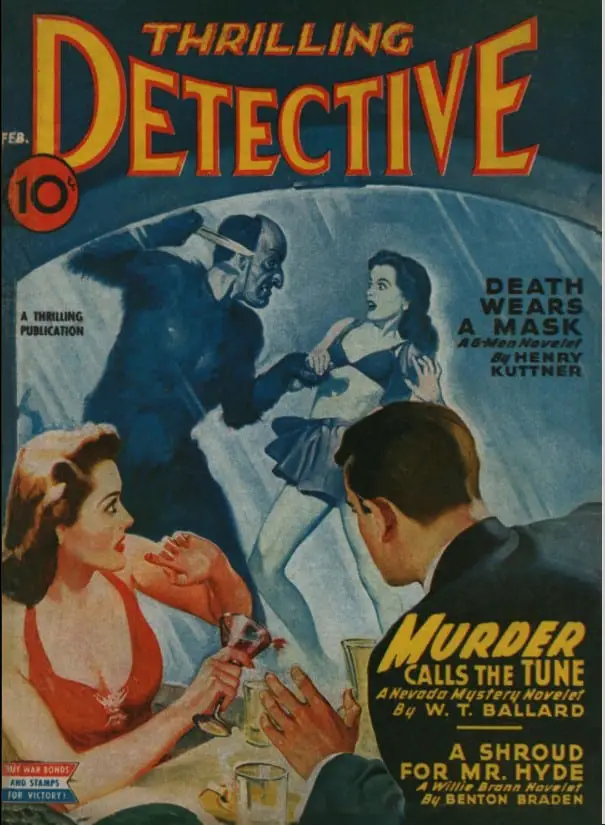

A stand-out example of a vampire horror story is “The Mask” by Richard Marsh, which appeared in Marvels and Mysteries in 1900. A homicidal madwoman adept in the art of mask-making transforms herself into a raving beauty and threatens to suck the blood of the hero.

Types Of Masks In Storytelling

…masks depend on people for care, and the people depend upon the masks to acquire certain states of control over their environment which are normally beyond human means of achievement … Power is an important concept here. If

Harold Blau,

mistreated, the masks have vengeful powers, which act as important sanctions.

Actual Masks

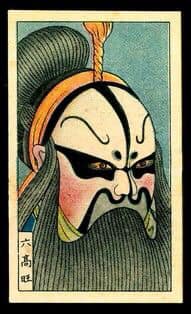

Masks are used in all cultures around the world, especially in rituals and ceremonies. Masks play an important social function.

The masks used in ancient Greek theatre are based on the culture of the ancient Dionysian cult. Thespis was the first writer to use a mask in stage writing. Members of the chorus wore masks to distinguish them from the main actors. There was a good logistical reason for this: The same actors were able to play a variety of roles in the same play. Also, the actors were men. Masks allowed them to play women, starting a tradition which is still utilised today (problematically).

Another logistical reason for stage masks: A bland-featured mask utilised over and over again distracts from the individual character and forces the audience to focus on that character’s actions.

Posing As Someone You’re Not

These characters are based on the ancient trickster archetype.

Behaviours include:

- Bluffing to secure social or economic advantage (Jen Barber in The IT Crowd).

- Dressing in disguise to get away with a crime (the pigeon in the pilot episode of We Bare Bears)

- Acting as someone with a different personality (Nom Nom the YouTube sensation Koala in We Bare Bears acts loveable but is actually evil.)

Walter White makes out he’s a nerdy, science teacher type (which works because he was), when in fact he’s the local drug lord.

The 2003 movie Thirteen by Catherine Hardwicke is a coming-of-age drama about two girls who pretend to be what they’re not. The structure involves the coming off of a mask. For much of the movie Tracy Freeland is acting as a pseudo-adult, ditching her mother who she still needs very much in favour of a girl who has not been so well protected from the world. How does Hardwicke wrap up this story? It’s a story chock full of conflict — arguments with Tracy’s mother, father, brother, teacher and former best friends. Therefore the ‘big struggle sequence’ needs something extra. In this case it’s the coming off of the mask. After rejection from Tracy’s mother, Evie Zamora outs Tracy to everyone as a thief, self-harmer, drug abuser and all-round evil person. While this portrait of her is not quite right either, it is in this scene that Tracy’s mother finally gets the full picture regarding what’s been going on with her daughter. The mask is finally off. In the outtake scene we see Tracy on a roundabout (a regression to childhood), emitting a primal scream. The torment of keeping up this facade of rebel has passed.

American Beauty involves two big masks: The teenage beauty who pretends sexual experience to disguise her complete inexperience, and the military neighbour with internalised homophobia. This contrasts with Kevin Spacey’s character, who takes off his mask at the beginning of the film and lives as his true, lazy, hedonistic self.

In some ways, Office Space is the comedy version of American Beauty. After hypnosis gone wrong, the hedonistic, don’t-give-a-damn side of Peter Gibbons is left. Comedy comes from the fact that this works to his advantage. Peter is now seen to have ‘leadership qualities’. Nerdy office workers pretend to be money launderers, knowing nothing at all about money laundering. This is a film with masks at every level — even the guy selling homeless magazines door-to-door is a well-spoken college student.

In both American Beauty and in Office Space, the double-identity characters are set up in contrast with people living as their true selves. Peter Gibbons meets a waitress who is so true to herself that she quits her horrible waitressing job by giving her boss the middle finger over an argument about not showing enough ‘flair’. Joanna is literally unable to pretend to be who she is not. Joanna in turn contrasts with her hyper-enthusiastic (but fake) boss. Michael Bolton is another character unable to fake anything with conviction, which is why it’s so funny to watch him try to pretend (in an important job interview) that he likes the singer Michael Bolton. Another character living his true life is Peter’s redneck labourer neighbour, whose basic urges make him crass but also relatable. Office Space has a happy ending because every character is living life as their true selves, ditching fake identities. American Beauty is a tragedy because characters are punished for their false presentations. In both films the message is identical: Faking who you are cannot possibly lead to happiness.

Makeovers

In the “Hello Nails!” episode of Kath and Kim, Kim gives Sharon a makeover. In a comedy, a makeover is a sure sign that the story will have the structure of transgression comedy.

Makeovers in non-comedies are often supposed to ‘reveal’ one’s true attractiveness, matching the attractive personality underneath. This is a fairytale view of humanity — that ideally, good people should look beautiful otherwise there’s an uncomfortable dissonance.

In comedies the real self is the unadorned version, which is why things don’t work out when the awkward, gawky Sharon Strezlecki tries to dress elegantly.

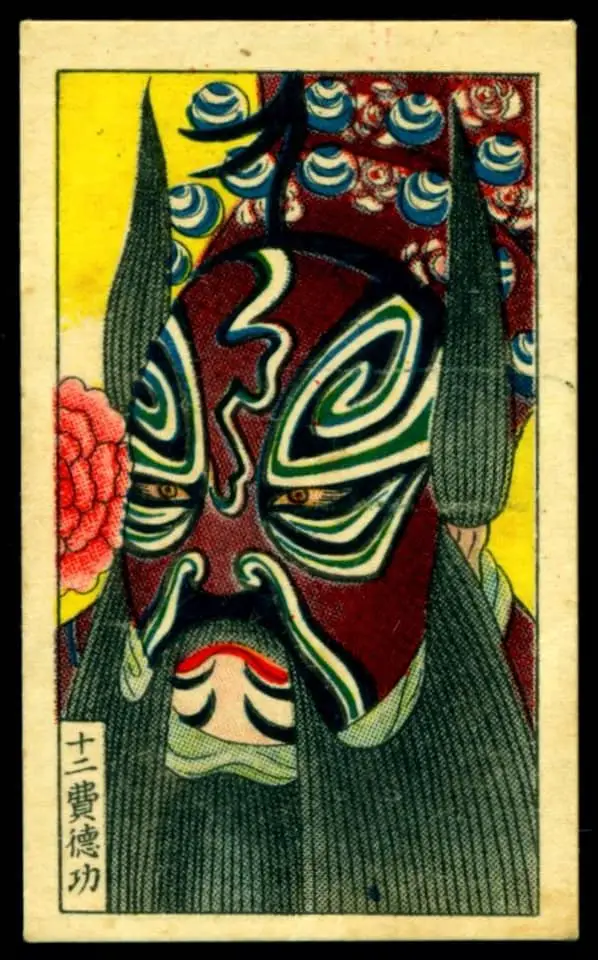

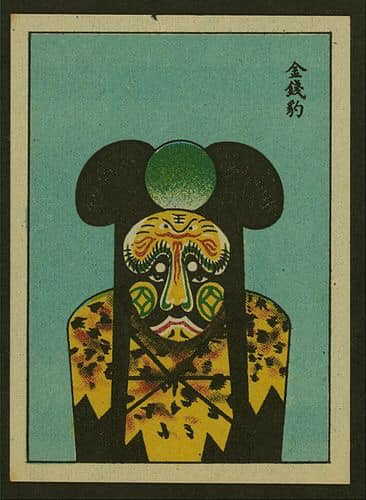

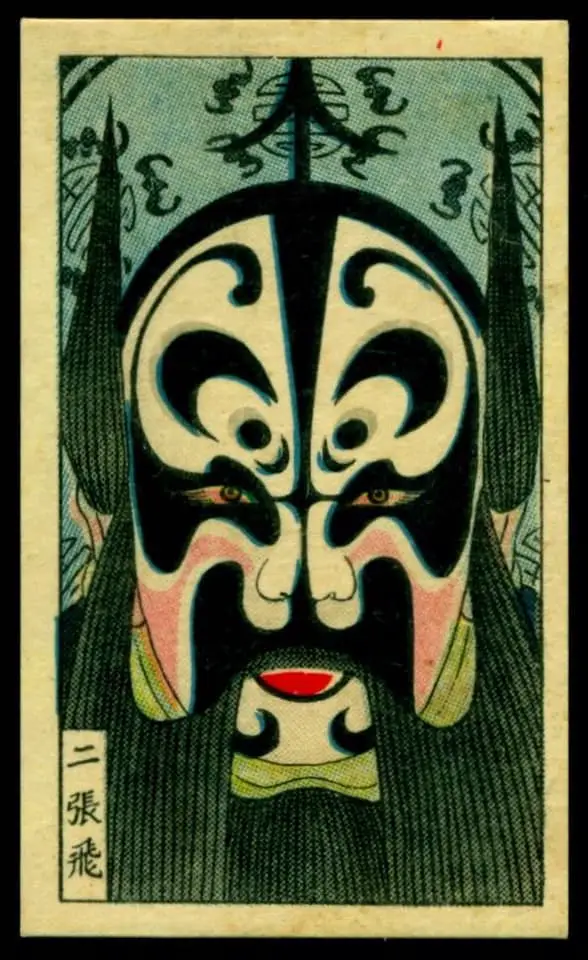

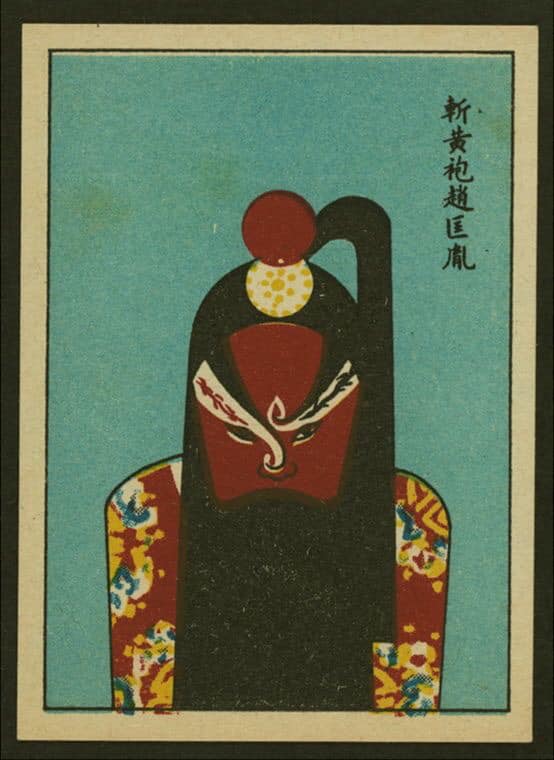

Chinese Opera Masks as illustrated on cigarette cards 1920s

Cross dressing

There is one type of mask often used in comedy, and it is used in almost every major children’s film. At some point a male character dresses as a female character to achieve some goal.

I feel Tootsie becomes more problematic as time goes on, with transgender feminists pointing out for us the downsides of equating feminine presentation with duplicity. In Tootsie, at least, Dustin Hoffman’s character dresses as Dorothy not with the main intention of exploiting femininity by bewitching men with fake feminine wiles, but in order to apply for jobs otherwise not open to him, and to disguise his own well-known male identity.

But in many stories for children, the male characters dressing as femme characters are using a mask of femininity to get away with behaviours which are manipulative in a sexualised way. A terrible example of that is the Australian middle grade book The Bad Guys by Aaron Blabey. Yet this is a very popular book and few question its ideology.

This storyline is highly problematic. The message is that femininity equals duplicity >> women are manipulative liars >> “Lock her up”.

I’ve said more about that here: Liars in Storytelling.

Masked Settings

The lovely setting later revealed to be hiding misery and crime is the setting equivalent of peeling a mask off a person. The masked setting is known as a snail under the leaf setting.

This is why mystery stories often work well thematically in tranquil little towns. The crime peels back the mask of civility to reveal the more troubling reality beneath the surface.

See also: How Can Setting Be A Character?

Are Western Storytellers Correct?

A few years ago I read a book called The People You Are by Rita Carter, which presents quite a different thesis of human behaviour.

Carter’s main argument is that there is no ‘one true self’. She argues that humans have the ability to change according to circumstance, and that we are rewarded for doing so. We are one way with our colleagues, another way with our families, and neither one of these ‘people’ takes precedence over the other.

The dominant idea in modern storytelling contrasts with this psychological view. No matter the genre, we are told time and again that that there is ’one true self’. This version of the self must make its way to the surface and be somehow ‘exposed’ before happiness can be found.

This view of human nature may age contemporary stories in the way that ‘one true love’ romance stories now seem old-fashioned to us, in the era of serial monogamy. Some pushback on that:

My problem is that people always say ‘don’t be afraid to just be yourself!’ and like…it’s not that I’m afraid, I just don’t know how to do that? Because I want to get super jacked and tattooed and never wear make-up and have plaid shirts and shave off my hair, and I also want to wear pretty dresses and high heels and learn how to do eyeliner properly and grow my hair out real long, and I want to be intimidating and confident and Speak My Mind and Take No Shit but I also want to be soft and kind and for people to think I’m cute, and I want to be seen as smart and well-read and respected but I also want to be seen as down to earth and approachable and fun…and I have no idea which if any of those people are actually ‘myself’ or if they’re all just a variety of exciting disguises.

Blog of Impossible Things

Since culture prioritises the view of the personality as a ‘singlet’ (hence the popularity of astrology, as explained in Carter’s book), readers generally have little time for a fictional character who does one thing in one context, then seems to be completely different in another. Multiple selves in a single character may be one of those things which doesn’t work too well in fiction even if it would reflect real life. Certainly, if not written well, the reader may blame the author for failing to create an authentic and consistent personality, even though none of us is one hundred percent consistent in real life.

I believe moving past this idea of ‘one true self’, which includes all stories in which someone ‘finds’ their ‘true self’ needs a bit more pushback. It might be closely related to moving past the gender binary, and has particular impact on those who live in a more gender expansive manner, which is hopefully all of us.

SEE ALSO

Twins, arch-nemeses, imagined selves, ‘Sliding Doors plots‘… all of these are used in fiction to convey the idea of multiple selves without actually writing multiple selves.

In politics and economics, a Potemkin village is any construction (literal or figurative) whose sole purpose is to provide an external façade to a country which is faring poorly, making people believe that the country is faring better.

The best knock-offs in the world are in China. There are plenty of fake designer handbags and Rolexes but China’s knock-offs go way beyond fashion. There are knock-off Apple stores that look so much like the real thing, some employees believe they are working in real Apple stores. And then there are entire knock-off cities.

Duplitecture, 99% Invisible

FURTHER READING

“Be Brave. Be Real. Be Weird.” The perfect tagline for a middle grade novel about removing the mask and being happy.

A moving middle-grade debut for anyone who’s ever felt like they don’t belong.

Brian has always been anxious, whether at home, or in class, or on the basketball court. His dad tries to get him to stand up for himself and his mom helps as much as she can, but after he and his brother are placed in foster care, Brian starts having panic attacks. And he doesn’t know if things will ever be “normal” again . . . Ezra’s always been popular. He’s friends with most of the kids on his basketball team—even Brian, who usually keeps to himself. But now, some of his friends have been acting differently, and Brian seems to be pulling away. Ezra wants to help, but he worries if he’s too nice to Brian, his friends will realize that he has a crush on him . . .

But when Brian and his brother run away, Ezra has no choice but to take the leap and reach out. Both boys have to decide if they’re willing to risk sharing parts of themselves they’d rather hide. But if they can be brave, they might just find the best in themselves—and each other.

The Intimate Act Of Performing Pain by Caroline Reilly. For chronically ill people, masking pain is a form of protection.

Header painting: Arthur Hughes – The Property Room