“Marriage á la Mode” (1921) is a Modernist short story by Katherine Mansfield, first published in a December edition of The Sphere: An Illustrated Newspaper for the Home. Magazines don’t normally publish summery stories in winter, but it makes more sense to know this magazine was aimed at British citizens living in the colonies.

This story was later published in The Garden Party And Other Stories.

Love letters are a risky business. Revealing yourself to another person opens the risk of rejection, but if you had to do it onstage? What if the recipient of your ardour and your expression of vulnerability thought it was funny, and shared your most private, loving self with others for jokes?

Have you ever sent a love letter? What about a revealing email? A selfie? A naked selfie? This story is 100 years old, but we are still sharing ourselves with others in ways that leaves footprints. In fact, we now do this in a variety of uber-revealing ways. People we trust still betray us by sharing our secrets more widely, without our permission. With the Internet, the size of the audience, and the size of possible shame, has grown many times over. The point of shame in this story is probably even more relatable to a contemporary audience.

This specific kind of betrayal has been explored in other works of fiction. Take “My Mother’s Dream” by Alice Munro. The narrator writes of her dead father:

…the cute and perky girls, who had run after him, writing him sentimental letters and knitting argyle socks? He wore the socks when he could, he pocketed the presents, and he read the letters out in bars for a joke.

“My Mother’s Dream”, Alice Munro

In “Marriage á la Mode” the trespass is even worse. This is a spouse making fun of her life partner, the person she vowed to love and respect.

Why would a wife read her husband’s heartfelt love letter aloud to their mocking friends? What’s the psychology behind it? This is the question Mansfield explores and foregrounds in “Marriage á la Mode”.

Everyone has friends who were killed in the War. Everyone gives up something when they marry.”

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

THE TITLE

Why has Katherine Mansfield called this story “Marriage á la Mode”? I have no idea if this has anything to do with anything, because the phrase “Marriage á la Mode” had entered the general lexicon by the time Mansfield wrote her (possibly completely unrelated) short story but there’s a famous series of narrative paintings that also go by this name.

Marriage A-la-Mode is a series of six pictures painted by William Hogarth between 1743 and 1745, intended as a pointed skewering of 18th-century society. They show the disastrous results of an ill-considered marriage for money or social status, and satirises patronage and aesthetics. … Hogarth challenges the traditional view that the rich live virtuous lives, and satirises arranged marriages. In each piece, he shows the young couple and their family and acquaintances at their worst: engaging in affairs, drinking, gambling, and numerous other vices. This is regarded by some as his finest project…

Wikipedia, where you can also see the paintings.

(Incidentally, Hogarth also created the famous Harlot’s Progress paintings and etchings, a story archetype which we can apply to a great many stories.)

I’m just going to assume Mansfield was familiar with the Hogarth series of paintings by the same name.

So, to what extent might she be using the Hogarth illustrations as pastiche? A National Gallery art critic describes Hogarth’s character development of the Countess in the paintings like this:

- a sniffling teenage girl in scene one

- turns into a sly sex kitten in scene two

- a sybaritic (self-indulgent) grande dame in scenes three, four and five

- and a remorseful suicide in scene six

As for the setting of the paintings, ‘there is no moral centre in this world; its empty values lead to disease, unhappiness and violent death’. The art critic suggests late 1990s analogues for Hogarth’s characters: ‘Nowadays at the Countess’s morning levee you’d find a pop star, an interior decorator, an astrologer and maybe an art dealer. The Earl would be just as likely to pass out from a surfeit of cocaine than from drink. Otherwise, not much seems to have changed since 1744.’

For a modern reader untrained in art history, Hogarth’s paintings are difficult to read without an art critic guiding you through. Importantly, though, these paintings were easily decoded by a 1744 audience of all levels of education. Tropes change. Symbols change.

Pehaps this has been said many times and I’m pointing out the obvious, but it seems Mansfield has borrowed Isabel’s emotional arc from the same-named Hogarth paintings. In her marriage to Charles, she started out as a teenage girl (even after two children she still looks 14), she is subsequently drawn into a world of ‘sly’ friends whose sexuality defines them. She self-indulgently reads her husband’s letter for their amusement and then, when alone, she is remorseful.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

William

The story opens on a Saturday afternoon with a man called William on his way home from London to spend Sunday with his family, disappointed with himself that he’s once again forgotten to buy a gift for his two young sons.

Notice how William relaxes fully when stretched out in his first-class smoker. He ‘flings down’ in the corner of the carriage and is most at home when busied with his work. This activity quietens the ‘familiar dull gnawing in his breast’, which I imagine, in contemporary langauge, is ‘anxiety’. (Later in the story Mansfield does use the word ‘anxious’ to describe William.)

There’s also a contemporary phrase for how William commandeers his own space on the shared public transport: “Manspreading”.

It’s interesting to consider that a privileged, well-salaried white man taking up more than his share of space in the world (symbolised by his spreading out on the train) might privately feel so invisibilised in his own home with his own family.

The servants were talking as if they were alone in the house. Suddenly there came a loud screech of laughter and an equally loud “Sh!” They had remembered him.

“Marriage á la Mode”

Mansfield counterbalances the empathy we might feel for William by guiding the reader through his unkind judgements as he looks out the window. He decides a red-faced woman is ‘hysterical’ (a.ka. “crazy”, straight from the misogynist’s playbook), and the ‘black-faced workman’ is ‘filthy’. This upper-class feeling of abjection for lower socio-economic classes plays out as a generalised feeling of disgust which goes well beyond a denotative description of dirt on a face. In 1920s London, the poor were literally considered a different breed. (Katherine Mansfield herself imagined she felt affinity for the servant class, possibly because she felt so different from her own family. This comes across in her writing.)

Isabel isn’t the only character in this story trying on another reality for size. Mansfield is making use of a technique known as ‘side-shadowing‘ when she shows us how William imagines being greeted by his wife:

The same thing happened every Saturday afternoon. When he was on his way to meet Isabel there began those countless imaginary meetings. She was at the station, standing just a little apart from everybody else; she was sitting in the open taxi outside; she was at the garden gate; walking across the parched grass; at the door, or just inside the hall.

And her clear, light voice said, “It’s William,” or “Hillo, William!” or “So William has come!” He touched her cool hand, her cool cheek.

The exquisite freshness of Isabel! When he had been a little boy, it was his delight to run into the garden after a shower of rain and shake the rose-bush over him. Isabel was that rose-bush, petal-soft, sparkling and cool. And he was still that little boy. But there was no running into the garden now, no laughing and shaking. The dull, persistent gnawing in his breast started again. He drew up his legs, tossed the papers aside, and shut his eyes.

“Marriage á la Mode”

If the history of art is anything to go by, the imaginary woman staring out to sea (or whatever) has sustained many a man on a long journey. And really, who doesn’t long to be greeted warmly after returning home after a long absence?

That said, it’s not lost on me that William is conflating his wife with the childhood memory of a bush — a very sensuous bush, but still. A bush. Surely Mansfield is poking a little fun at William, so we might understand how Isabel could dismiss him as ridiculous, later in the story.

And it’s not lost on me that William (for all we know) hasn’t given a single thought to his sons (nor to Isabel?) until he’s literally on the train home to see them. Otherwise, we might deduce, he’d have found the boys gifts during the week. He seems to be a man who buries himself wholly in his work. Like many men of that era, continuing into the present, he has been acculturated to believe that his main contractual obligation to his family is providing in an economic sense.

He has now referred to Isabel’s friends as “precious” and “poets” which is a clear indication that he doesn’t have much time for the arty-farty flaneurs of this world. There is only one correct way to be a man, and William is it.

The word “poet” may be used euphemistically here, as it was in gay personal ads of early 20th century London. When men quoted certain poets and writers, they were signalling their orientation. This may seem hopelessly euphemistic to a modern audience, but to quote Edward Carpenter, Oscar Wilde or Walt Whitman in a 1920s personal ad was widely understood by all at the time to be blatantly, dramatically, outrageously gay.

Paddy and Johnny

The sons are indistinguishable from one other, typical kids. They expect as much from their parents as the parents can give, always angling for more.

These two are particularly ‘spoilt’, to use an old-fashioned word. When Mansfield tells us the boys have access to ‘Russian toys, French toys, Serbian toys — toys from God knows where’ she is telling us that William has the earning power to provide a very nice upper-middle class life for this English family. (Either that or a salaried position combined with inherited wealth.) The boys are generous handing around their sweets, probably because they’re privileged and understand there’s always more where those came from.

Isabel

We hear of Isabel before we ‘meet’ her on the page. Whereas William is described in the very first sentence as a sentimental type, his wife Isabel has ‘scrapped the old donkeys and engines and so on because they were so “dreadfully sentimental” and “so appallingly bad for the babies’ sense of form”.’

She is such a snob that she thinks a visit to a major art gallery (The Royal Academy) would be ‘certain immediate death to any one…’ Here’s the book all about the works on display at The Royal Academy in 1920 in case you’re interested to see the work which Isabel comically sees as beneath her and her boys. We already know that Isabel wants to be different. Her greatest fear: to be run-of-the-mill. What an unfortunate position to find yourself in, then: married to a well-salaried man, living in the 1920s equivalent of suburbs having produced not one but two male heirs. Isabel has done exactly as the world expects of a woman.

Why might Isabel eschew the sort of art on display at a national institution such as The Royal Academy? Could it be because certain artists have been excluded from that building? Could it be too hegemonic for the alternative Isabel?

And what to make of Mansfield’s phrase ‘The new Isabel’? The word ‘new’ stands out like a beacon to the reader.

“It’s so important,” the new Isabel had explained, “that they should like the right things from the beginning […]

The new Isabel looked at him her eyes narrowed, her lips apart.

“Marriage á la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

We are clearly seeing Isabel through William’s eyes at this point in the story, though her new persona is the narrator’s judgement as well. She’s trying something on for size, and William has begun to notice. But what? And why?

“ISABEL’S PRECIOUS FRIENDS”

William describes the friends as a bunch, not as individuals. He hasn’t observed them keenly enough to tell these intruders apart:

Isabel’s precious friends didn’t hesitate to help themselves… Isabel’s young poets

This small group of friends consider themselves family, in it for the long haul:

“Paint what?” said Bill loudly, stuffing his mouth with bread.

“Us,” said Isabel, “round the table. It would be so fascinating in twenty years’ time.”

“Marriage á la Mode”

MOIRA MORRISON

William blames Moria Morrison for changing his wife into something she was not when he met her. The trip to Paris seemed to nail the coffin of old Isabel;

But the imbecile thing, the absolutely extraordinary thing was that he hadn’t the slightest idea that Isabel wasn’t as happy as he. God, what blindness! He hadn’t the remotest notion in those days that she really hated that inconvenient little house, that she thought the fat Nanny was ruining the babies, that she was desperately lonely, pining for new people and new music and pictures and so on. If they hadn’t gone to that studio party at Moira Morrison’s – if Moira Morrison hadn’t said as they were leaving, “I’m going to rescue your wife, selfish man. She’s like an exquisite little Titania” – if Isabel hadn’t gone with Moira to Paris – if – if …

“Marriage á la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

(Titania is a character in William Shakespeare’s 1595–1596 play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the play, she is the queen of the fairies. Due to Shakespeare’s influence, later fiction has often used the name “Titania” for fairy queen characters in general.)

Because this is Katherine Mansfield, who had husbands, “wives” and everyone in between, I read an erotic aspect into the relationship between Isabel and Moira, even before the campness of her friends is made unambiguously evident within scenes. Moira clearly feels aesthetic attraction for Isabel, at the very least.

Bobby Kane

At first I think Bobby Kane is Isabel and William’s servant because he’s garnered an infantalising nick name and he’s also been charged with the job of buying sweets. Then he’s required to sit next to the driver, but when he speaks, his language is highly descriptive and poetic. I understand at this point that he is one of “Isabel’s Poets”.

“I’ve chosen them because of the colours. There are some round things which really look too divine. And just look at this nougat,” he cried ecstatically, “just look at it! It’s a perfect little ballet.”

Like a child, Bobby Kane hasn’t paid for the sweets himself. Isabel pays for them when the shop owner comes out, and Bobby goes from looking scared to delighted, again childlike. This detail tells us that Isabel (and William, by extension) are paying for the poets’ life of leisure. This is no doubt part of Isabel’s appeal to the poets, who have positioned her as their mother figure.

Of course, effeminate men were locked out of the well-paid workplace as women were, so finding a ‘fag hag’ benefactor was one way to get by in such overtly discriminatory times. That said, Isabel’s relationship with her friends is as commensal as her relationship with her husband. Let the record show, the husband himself enjoys a commensal relationship with patriarchal capitalism. Everyone is someone else’s bitch.

Bobby Kane is wearing no hat (‘bareheaded’ was unusual in those days) and is dressed all in white. A white suit was probably made of linen. In short, he’s wearing 1920s men’s casual wear. Without a hat, with his sleeves ‘rolled up to the shoulders’ he was inappropriately attired, and dressing to show off his biceps (not just for the heat).

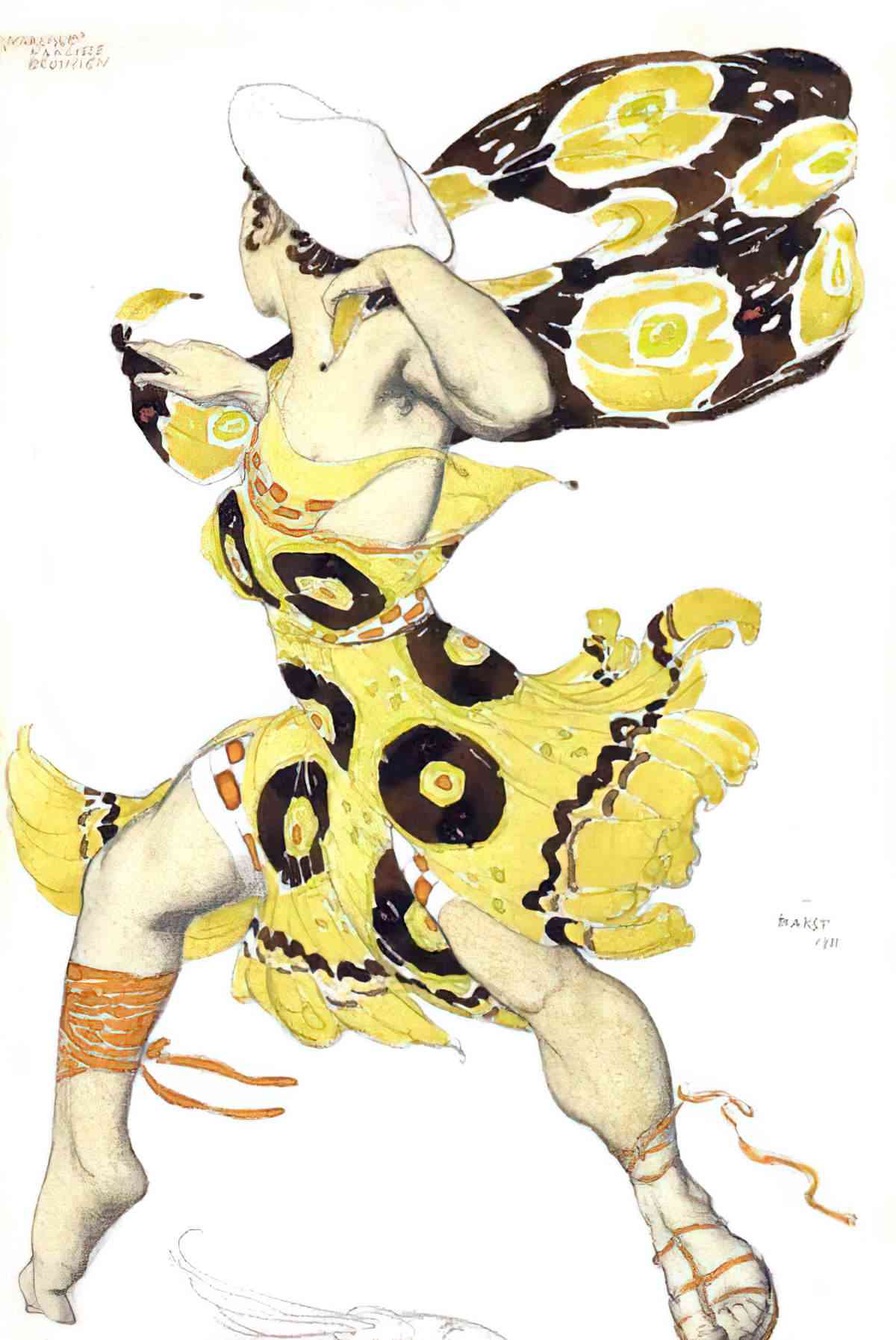

What does Bobby mean when he asks if he should wear his Nijinsky dress? Maybe he means the famous photo of Nijinsky dressed as a mostly naked faun, or maybe he means something like this:

Bill Hunt

Bill is better able than the other Poets to try and draw William into the social scene around Isabel, though he ultimately fails in that. William is simply too different.

Dennis Green

Isabel’s friend Dennis playfully flirts with the strait-laced William:

We shall have to anoint ourselves with butter,” said Dennis. “May thy head, William, lack not ointment.”

William sees this flirtation for what it is. But rather than join in, says he’d better sit up front near the driver.

Dennis’s main role in the story is to provide comnedic commentary, turning their everyday happenings into the titles of yet-to-be-created works of art e.g. “A Lady with a Box of Sardines”, said Dennis gravely. It’s unclear whether Dennis is speaking with intended gravity or whether he’s mocking himself and his own people. Either way, Mansfield is using him as a choric figure.

SETTING OF MARRIAGE A LA MODE

WEATHER

When William meets Isabel at the station with her annoying poet friends in attendance, it is a very hot day, so hot that they’ve tried to find ice (and failed). Is Mansfield using the heat metaphorically here? Hot as in erotic? In describing the weather is she describing a sexual charge permeating across this band of poets, zipping through Isabel, skipping William?

LOCATION

As far as I can make out, “Bettingford Station” is not a real place, but is English enough to sound like a realworld station, somewhere South of London (‘he was taking nothing down to the kiddies’).

This story happens around London, the London of 100 years ago. Katherine Mansfield herself was very familiar with this culture after three years at Queens College, right in the heart of the city. Queens College was remarkably progressive for its time, and allowed its girls to go walking about unchaperoned! (So long as they went in pairs.) Mansfield and her sisters lived wonderfully cultured lives, visiting cafes and art galleries and restaurants. (What did Mansfield make of The Royal Academy, I wonder. Is she parodying the snobbish Isabel or did she really find it kitsch?)

QUEER LONDON

Allocishet people living in the 1920s typically had a complete and utter conceptual hole in their understanding of attraction and gender identity. (Even today people often conflate the two.) The concepts of heterosexuality, bisexuality and homosexuality only started to appear in medical journals in the late 1800s. These words and concepts took much longer to become mainstream.

It would never cross William’s mind that Isabel might be enjoying a separate erotic life with her poet freinds, because good wives and mothers were thought to be devoid of sexual desire, for starters. And lesbians? What are lesbians, exactly? If the 1920s concept of lesbianism were understood, the word ‘bisexual’ referred only to certain types of organisms. If Isabel is bi-, William will never see that because she is married to him. His binary view of men, women and sexuality will keep him blind.

All up, there is simply no way that a straight-edge man like William is ever going to understand what the Japanese called the ‘floating world’, and which was absolutely thriving in 1920s London (and New York, and Paris), before the dominant-culture straights ever learned about it, and tried their darnedest (in the 1950s and 60s) to eradicate queer spaces entirely.

A LITERARY ALLUSION

There’s an illusion to a play which became more and more popular over the 20th century, especially in amateur theatre: The Maid of the Mountains. The play gained in popularity after it was made into a film in the early 1930s.

On their way back to the house from swimming, we catch the tail end of Moira trying to persuade Isabel to persuade William to buy them all a gramophone so that they might listen to the soundtrack of this play. Isabel protests and urges Moira to be kind to William. In what way is Moira teasing William? Here’s what the play is about. It’s got a convoluted plot, but might we read Isabel as Teresa, who feels remorse for betraying her man? Or perhaps these characters think the play is an escapist piece of kitsch, and are making fun of William, who would be just the sort of straight-edge guy to buy a mainstream soundtrack like that, if he were to ever purchase something fun and frivolous such as a gramophone.

WHO IS WILLIAM BASED ON?

Katherine Mansfield’s father, Harold Beauchamp, was such an important man in New Zealand that he spent Christmas with Richard Seddon, and when in London, met with actual royalty, as you do. But Harold was not aristocracy himself. He was more like William, who Mansfield created for this story: a man who is good at his job and able to provide a big country house with servants for his wife and children.

Has she recreated a fictional version of her own father? It’s an interesting thought, but can remain only a thought. When Isabel says in “Marriage á la Mode”, “But we couldn’t have gone on living in that other poky little hole, William. Be practical, at least! Why, there wasn’t enough room for the babies even” Mansfield might as well be describing the Beauchamp house on Tinakori Road, occupied before they moved to Karori. If you’ve ever visited the historic Tinakori cottage in Wellington, you’ll be amazed to see how ‘poky’ it is, especially when considering how many people were living there: The Beauchamps plus Annie’s mother and two younger sisters, three babies. Harold Beauchamp did the New Zealand equivalent of moving his family from the capital out to the suburbs for a healthy country lifestyle, while remaining sufficiently proximal to maintain capital connections and salary.

We don’t know how much real power the fictional William wields. But Katherine’s father Harold Beauchamp was a genuinely powerful man, and after reading Mansfield biographies I don’t think he was short on confidence, though Mansfield surely noticed a gap between how Harold Beauchamp was regarded in the world and how ordinary he was in his own home. Surely this applies to all children of wealthy and famous parents. There’s the ‘public’ parent and the ‘parent at home’. There will always be a difference.

Biographers have said that Annie — Harold’s wife and Katherine’s mother — was pretty cold to her family in general, though I like to think Harold and Annie made good travelling companions. They spent a good deal of time travelling alone together without their children in tow. (The kids stayed in New Zealand and were looked after by Mrs Dyer, Annie’s mother.)

The Beauchamp couple spent so much time overseas that when Katherine did see her own parents, she’d have regarded them as strangers, perhaps with a more detached eye than if Annie and Harold had been a bigger part of her life. Most of us don’t regard our own parents as ‘real people’ until there’s some distance between us, typically after we become adults ourselves and leave home. Mansfield would’ve experienced that view of her parents a lot earlier.

It’s possible the young Mansfield observed an anxious-avoidant dance between her parents, always a little strange to her, with Harold seeking more connection and Annie seeking more independence. However, I can only guess about that. Perhaps Mansfield experienced this dynamic in one of her own relationships, or witnessed it among friends. At any rate, the presentation of this dynamic in a fictional story shows Mansfield witnessed it somewhere.

It seems likely to me that Mansfield observed it first in the non-queer but somewhat transactional marriage between her parents, and then later experienced the masking required of Isabel herself.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MARRIAGE A LA MODE

SHORTCOMING

Mansfield paints a picture of two people in two very different marriages. Unfortunately for them, it’s the same marriage. It may be a mixed orientation marriage (MOM) — a straight man married to a queer woman.

We can say for sure that Isabel craves a freer kind of life. Isabel is hemmed in by the strict societal expectations for upper-middle class mothers.

DESIRE

William wants to spend weekend leisure time with his wife and two sons. He wants to feel important to them.

OPPONENT

Isabel has different plans, or rather, has found herself among people who have turned themselves into furniture around her home, making plans for her. These people are her friends, yes, sure, but they are also using Isabel to access William’s wealth.

These friends don’t respect William as a person. They find him boring and ridiculous. To them, he must represent the exact life they abhor, a hegemonic life from which they are excluded.

PLAN

The plan has already been set in motion: The Poet friends have basically moved in with Isabel. At Isabel’s they swim, sleep, party and eat like kings. This works for the most part, because Isabel’s husband is based in London.

We can see throughout this story that Isabel is starting to push back on this plan of theirs. She suggests sardines for dinner (a cheap fish) but the following day she realises the salmon she’d planned to eat sparingly has mysteriously disappeared. The reader, alongside Isabel, realises she’s being taken advantage of. Although this couple is well-off, they are not so wealthy that their riches are a bottomless pit.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘battle’ of this story is the reading of the private letter, to an audience who laughs at William as the butt of their joke.

Isabel does this heinous thing to her husband, and when it comes to heartstrings, mine are in sympathy with William.

ANAGNORISIS

But it’s easy to forget what it was like for women living in the 1920s, pre- birth control, pre- equal rights in the workplace, pre- equal pay for equal work, and so on. This lack of freedom applied to the wealthy women like Isabel as well as to the women lower on the foodchain.

We learn, too, that she married young, so young in fact, that even after having children she still looked to William like a teenager:

Isabel wore a jersey and her hair in a plait; she looked about fourteen.

Is Mansfield inviting us to cast judgement on Isabel by setting her up as a false person with no true identity of her own?

If Isabel is craving a bit of a party life, that’s because she had no adult life of her own before becoming a mother.

Modern audiences are harsh on a character who behaves differently in different situations. We call these people ‘fake’. We don’t trust them. I should say WEIRD readers (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic) have little time for these characters, because other cultures (especially East Asian audiences) appreciate that different situations require different behaviours in order for a society to function.

William is an example of a fictional character who remains wilfully, resolutely blind to his situation. This sort of story ending has been called the ‘antiepiphany’. Mansfield was a fan. It’s a feature of Impressionist narrative that people don’t really change. (Likewise, Laura decides not to understand anything at the end of “Her First Ball”. )

We suspect that William had his chance to understand what’s really going on in his own house, if only he’d read some of the poems he found pushed down the side of the couch:

One fished up yet another little paper-covered book of smudged-looking poems … He thought of the wad of papers in his pocket, but he was too hungry and tired to read.

“Marriage á la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

Or maybe there’s nothing of use in the poems per se; this reluctance to know what’s been stuffed down the side of his own couch is more symbolic of a wider propensity to Not Look.

But on the page, it’s actually Moira who is shown to literally shut her eyes:

Moira was asleep. Sleeping was her latest discovery. “It’s so wonderful. One simply shuts one’s eyes, that’s all. It’s so delicious.”

“Marriage á la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

Ironically, of all the characters in this story, Moira has the best handle on the socio-economic dynamics between the entire cast. She knows that her two gay friends are hanging around Isabel for Isabel’s ability to pay for things like salmon, and for her nice big house within easy distance of their spiritual home of London. Moira knows that Isabel is only play-acting this suburban life of matrimony, and it’s only a matter of time before Isabel will drop the mask with her, if she hasn’t already.

What is the meaning of “marriage lines”? Unfortunately if you search for this phrase the feed is clogged with a whole lot of rot about palm reading.

The characters in this short story clearly aren’t talking about that. They seem to be talking about the marriage vows, but then why does one of the party think “they’re only for servants”? An artlcle called Living in sin: unmarried relationships in Victorian Britain offers part of the answer:

For the Victorians, relationships outside marriage tended to be surreptitious rather than openly acknowledged. The poor, dependent upon landlords, employers, and occasionally charity, needed to maintain a good reputation just as much as the wealthy, if not more so. The diarist and clergyman Francis Kilvert wrote of one couple being evicted from their home simply because they were unmarried, and the receipt of social support could depend on showing one’s ‘marriage lines’. This was a society that drew a sharp distinction between the married and the unmarried.

Here is an excellent run-down of “marriage lines” and why the marriage certificate was given to the bride, not to the groom. (tl:dr; A woman’s status in life was heavily tied to her status as a wife. The marriage certificate was therefore given to her.)

When Isabel sees her friends not as four but as forty, they have turned into a swarm rather than a group, their presence no longer wanted. She includes herself as one of the four: ‘shallow, tinkling, vain’. (She’s gone to her room to have this unwelcome epiphany about herself, similar to Miss Brill.)

NEW SITUATION

Isabel has become emotionally distant from her own husband, drawn into the world of her non-mainstream friends. They have helped teach Isabel to despise the world that William represents.

It is only by shaming him in the worst possible way, and by experiencing remorse, that she is able to remember that she loves him. She feels pity for him, which is her way back into feeling love, reminiscent of many abusive dynamics.

At the very end she faces a clear, on-the-page moral dilemma:

Isabel sat up. Now was the moment, now she must decide. Would she go with them, or stay here and write to William. Which, which should it be? “I must make up my mind.”

“Marriage á la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

Mansfield first gives us a false ending, telling us that of course Isabel chooses her husband. But the final paragraph gives us the real ending: She chooses her friends, hoping to manage her friendships alongside her marriage. As a moral dilemma, Isabel’s predicament works well for narrative purposes. There is no decision she can make that is a good one. Perhaps some commentators see that there is a clear-cut right answer for Isabel: ditch the friends, be loyal to your husband, love.

But at what price to Isabel? She’s attracted to this queer communty for a reason.

In Katherine Mansfield: A Study of the Short Fiction, J.M. Kobler asks readers to consider two possibilities for Isabel. In Aristotlian terms, is she ‘incontinent’ or is she ‘self-indulgent’? Here’s the difference:

Incontinent: She knows the right thing to do. She just doesn’t do it. She doesn’t write to William, no matter how much she may want to.

Self-indulgent: She has no idea that what she’s doing is wrong, that she’s causing harm to her husband by prioritising her friends over him, and also depleting their finances by letting them leech.

Clearly, Isabel falls into the category of ‘incontinent’. Kobler goes into all the evidence in favour of incontinence over self-indulgence. Clearly, he is correct. Isabel knows full well the impact she’s having on her husband.

But commentators who avoid queer interpretation of Katherine Mansfield are missing an entire layer.

Queer by definition is whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an identity without an essence. ‘Queer’ then, demarcates not a positivity but a positionality vis-a-vis the normative–a positionality that is not restricted to lesbians and gay men, but is in fact available to anyone who is or who feels marginalized because of her or his sexual practices: it could include some married couples without children, for example, or even (who knows?) some married couples with children.

Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography By David M. Halperin

Queer theory is vital when getting to the heart of this story because it moves us away from asking what is natural versus unnatural, and forces us to readjust our lens to what is normative versus deviant. We can only understand how power works when we consider what the hegemonic culture considers normative. This includes power at the most personal level, even the power held between two individuals, within a marriage.

The really interesting question of “Marriage a la Mode” is this: If Isabel cannot prioritise William above her friends, the normative, non-deviant, obviously ‘correct’ choice, why can’t she?

Why is Isabel wearing a mask (the ‘new Isabel’, the ‘new’ laugh)? What is the function of this mask? There’s no way of answering that layer without asking why Isabel is drawn to this — very obviously, on-the-page — queer cast of friends.

The answer to this must be extrapolated. Mansfield was in no position to put this part of her stories on the page, however clear the implications may seem from the distance of 100 years later.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Katherine Manfield was an interesting personality and her biography inevitably becomes epitext.

Mansfield was described as often looking like she was wearing some kind of mask. In a more metaphorical sense, we know she jumped with enthusiasm at the chance to travel to the other side of the world and reinvent herself. She went by many names (though we remember her best as Katherine Mansfield). Her various names were a type of mask.

Katherine reinvented herself again when she left New Zealand the second time, never to return. Whatever we say about the fictional Isabel, we can say this for sure about her creator: Mansfield was someone who spent her life trying on various personas.

And why might she have done that? Ha. She was a woman. As a child she was dismissed as fat by her mother, the designated ‘difficult’ daughter, the smart, streetwise student who didn’t do well at school and wasn’t really expected to. She wanted to become a musician but was never quite good enough. Most significantly of all, perhaps, Mansfield was bisexual, when there was no word to even describe her orientation. The best Mansfield could do in imagining what it might look like to be attracted to women was to imagine herself married to a woman. (We see this in an erotic story she wrote as a teenager about her friend Vere). It was (at least for a long time) beyond even the highly imaginative Katherine Mansfield to imagine relationships modelled by contemporary relationship anarchists, for instance.

Of course Katherine Mansfield wore a mask. She was not brought up in an environment which allowed her to be herself. Whenever she stepped out of the closet, and let’s be honest, she was constitutionally not built to really ever be in it, she was punished for her transgression. She was sent back to England as a ‘remittance woman’ (to save her family from shame). Her friendships with girls at school had been considered unnatural, her subsequent relationships with men too hasty.

The character of mask-wearing Isabel did not emerge in a cultural vacuum. It’s simply not enough to conclude that Isabel is two-faced and leave it at that. By default this summons a misogynistic old chesnut: that women are simply built like that.

RESONANCE

Stories teach Western audiences over and over: you can’t be happy unless you’re living your authentic self, in public. Cue all the coming-out stories which dominate LGBT narrative, and all the picture books of the Elmer the Elephant variety, which teach us from birth that if we only feel proud of our individuality, everyone else will respect us, too.

But is that really true? Is it always safe to come out as gay? As gender diverse? As neurodiverse…?

Hell no. Let’s spare a thought for the Isabels of this world, required to keep their masks on, balancing their conservative lives against transgressive selves. The mask sometimes slips. Eventually it’s likely to fall off. But not yet.

Isabel is doing her husband subtle but very real damage by keeping it on. He can’t name it. He can’t put anything into words, because the words don’t exist in his world. He most certainly sees that Isabel has surrounded herself with gay friends, but he can’t see that she has chosen them as much as they have chosen her. Importantly, Isabel can’t name her feelings, either. The greater hermeutical injustice is done unto Isabel.

In “Marriage á la Mode”, I believe Mansfield was exploring the specific damage that culturally enforced inauthenticity can do to the unwitting partner in a traditional marriage, Queerness aside, marriages of this era were very often authentic in some ways (loving) but not in others (sexual). In fact, a marriage borne entirely of economic necessity was run-of-the-mill in an era when women’s only hope at a comfortable life was to ‘marry well’. Transactional interactions were enough. Other forms of attraction were a nice-to-have, but no reason to end a marriage.

I feel terribly for William, arse that he is. He’s a patriarch, make no bones about that, but when he’s not acting like a big manly man, he’s accused of being ‘sentimental’. This guy can’t win, either. The allocishet patriarchy is painful for everyone, ya see?

Sorry as I feel for William, has Mansfield painted a damning picture of two-faced party-gal Isabel?

Mansfield has painted a damning picture of marriage. Marriage as strait-jacket.

When it comes to the individuals depicted in this particular story, she’s given us enough info to apportion blame very carefully. We must use insight unavailable to the fictional, ignorant, hapless William: William, with all of his white, masculine, 1920s privilege and no genuine, human insight at all into his young wife.

William’s vision of Isabel will continue to exist mainly in the imaginary snippets of her he has learned to dream up.

FURTHER READING

Brindle, Kym. “‘Mysterious Epistles’: Letters Home in Katherine Mansfield’s Short Stories.” Journal of New Zealand Literature (JNZL), no. 38.2 (2020): 15–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26944126.

Header illustration: William Bolin, artist painting a woman in a wedding dress, 1924