The word ‘wink’ is sometimes used in relation to children’s literature. Below I take a look at how authors ‘wink’ at their audiences, and also compare the 20th century paternal wink to a more modern version, which includes the youngest readers rather than going over their heads.

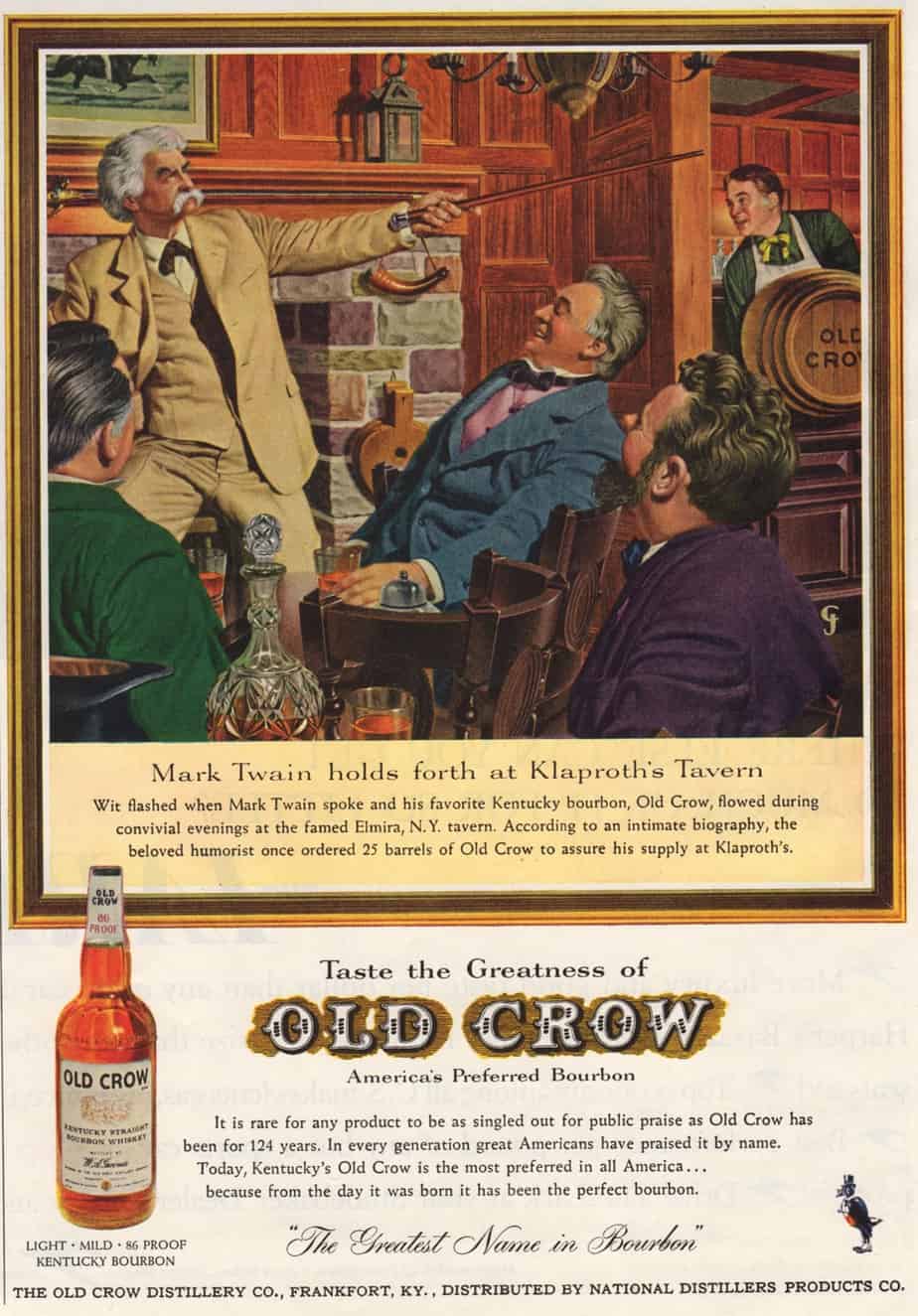

You may notice that each of the examples I’ve collected below are written by men. I’m not sure if this is a coincidence, but the Mark Twain Wink has a distinctly avuncular feel to it. I’ll be on the look out for examples of the Mark Twain Wink written by women, but they’re not as easy to find.

This doesn’t mean women have not ever written this exact humour. Take Jane Austen, and the famous first line of Pride and Prejudice:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Jane Austen

This is the narrator winking at the audience. As we read on, it might easily be the sort of witty observation that comes out of Mr Bennett, but it’s coming out of an unseen narrator with a character of their own. When these observations come out of a character rather than a narrator, the technique has been called The Mark Twain Wink, but we might also call it the Jane Austen Wink. Look for it especially in (male) avuncular characters, however. The gendering is still there. It’s no coincidence that Mr Bennett’s voice is the winky one — he is male, white, middle class, formally educated and the 18th century version of the ironic hipster.

The 20th Century Mark Twain Wink

“Can I have a pig too, Pop?” asked Avery

Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White

“No, I only distribute pigs to early risers,” said Mr. Arable.

In his Annotated Charlotte’s Web, Peter Neumeyer describes the above narrative technique as an example of a ‘wink’, explaining that the word ‘distribute’ is an unusual and humorously inappropriate choice. Neumeyer also proposes that White learned this humour from Mark Twain. (Ernest Hemingway said once that all modern literature comes from Twain.)

You don’t have to read far into anything by Mark Twain to find an example. From the first page of Tom Sawyer:

She did not finish, for by this time she was bending down and punching under the bed with the broom, and so she needed breath to punctuate the punches with. She resurrected nothing but the cat.

Tom Sawyer

The wink comes from the verb choice, ‘resurrected’, as an old lady searches for a naughty boy, thinking he’s under the bed. Do young readers understand the meaning of ‘resurrect’? They can deduce from context. But do they typically understand its wider connotations connected to death, and that the old lady is feeling comically murderous, and that Twain deems cats so lazy that they may as well be dead? Also on the first page:

She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out among the tomato vines and ‘jimpson’ weeds that constituted the garden.

Tom Sawyer

‘Constituted’ is another unexpected verb choice, comedic because of the dissonance between the pathetic plants described versus the ten dollar word ‘constituted’. This only serves to emphasise that the ‘garden’ is hardly worthy of being called a garden at all.

No Tom. So she lifted up her voice at an angle calculated for distance and shouted

Tom Sawyer

This is perhaps a less obvious example of a wink. Mark Twain is describing the frantic search for a naughty boy, and ‘calculated’ is hardly the state-of-mind we’d expect of someone angry and on a bit of a rampage. But again Twain has chosen a verb for its dissonance.

Back to E.B. White and the ‘distribute pigs’ example.

I borrow the term ‘Mark Twain Wink’ from Peter Neumeyer, who describes the technique as a ‘skewing’ or ‘dislocation of diction’. This wink appeals to a dual audience because only a sophisticated reader will fully appreciate it:

One may “distribute” candy, but hardly pigs, in a context such as this. … Thus, suddenly and ever so slightly, White has skewed the diction in his text, making Mr. Arable sound more like White, or like a narrator who winks at the reader over the heads of the characters.

Such “winking” is a device that was much used in the nineteenth century by writers such as William Thackeray, who employed it in his fairy tale The Rose and the Ring.

Although White now merely suggests his own bemusement through the voices of his characters, later he will break the surface of his story by using an intrusive narrator—an “I” voice—who actually steps right into the story to comment on proceedings.

The same Twain-like dislocation of the diction is seen in a letter White wrote to the vice president of the Consolidated Edison company when he was informed that his refrigerator might be discharging poisonous gas and that he should leave his window open: … ‘I do not want to open a window. It would be very unpopular with the cook.’

The Annotated Charlotte’s Web, Peter Neumeyer

Likewise, A.A. Milne also winked at adult co-readers of Winnie-the-Pooh. E.H. Shepard also winked via the illustrations. There is much irony between the words and the pictures, for example when Pooh is stuck in the hole because he’s eaten too much honey. Christopher Robin reads him a ‘sustaining’ book, which happens to be an ABC book, and opens to the page for ‘Jam’. Both Milne and Shehard make fun of the child.

It’s also in the narration. By opening chapters with “In which…” Milne establishes a formal diction we might expect of legal documents or committee meeting minutes. Dissonantly, each episode of Winnie-the-Pooh is famously about nothing much at all, where opponents are revealed to be nothing worth worrying about, where The Hundred Acre Wood is a utopia where nothing at all can hurt you.

Once upon a time, a very long time ago now, about last Friday, Winnie-the-Pooh lived in a forest all by himself under the name of Sanders.

Chapter 1, IN WHICH WE ARE INTRODUCED TO WINNIE-THE-POOH AND SOME BEES, AND THE STORIES BEGIN

(“What does ‘under the name’ mean?” asked Christopher Robin. “It means he had the name over the door in gold letters, and lived under it.”

“Winnie-the-Pooh wasn’t quite sure,” said Christopher Robin. “Now I am,” said a growly voice. “Then I will go on,” said I.)

Milne’s example goes beyond dissonant word choice and relies upon the adult’s understanding that to ‘go under the name of’ means it’s not your real name. Christopher Robin, child stand-in, asks what that means and the narrator gives him an incorrect definition. Together, A.A. Milne and the adult reader are laughing at the naivety of our child co-readers. In the next line, we laugh together at the child’s transparent wish to not seem stupid by pretending the question came from a stuffed toy. The adult is also laughing at the observation that, to children, ‘last Friday’ seems a very long time ago, because time seems to pass more slowly for children.

In The Mouse and His Child (1967) Russell Hoban also makes use of the Mark Twain Wink. The elephant in the toy shop functions as Charlotte the spider does in Charlotte’s Web and says this after The Child (a clockwork mouse) asks if the elephant is his mama:

“Certainly not!” snorted the elephant. “Really,” she said to the gentleman doll [actually to the adult co-reader], “this is intolerable. One is polite to the transient element on the counter, and see what comes of it.”

The Mouse and His Child, Russell Hoban

The mouse’s speech is genuinely childlike, like that of Wilbur. But in both Charlotte’s Web and in The Mouse and His Child, there is an adult-like character contrasting with the voice of the genuine child (main) character.

The Wink in Peter Pan and Wendy

In the story, Wendy hopes the boys will die like English gentlemen. She is genuine when saying it but the knowing audience realises Wendy is acting the part of a mother rather than actually being mother. This parallels how the boys are playing at death. There is a message here for the audience who understands the difference between reality and play, and as Diane Purkiss puts it in her book about fairies and fairy stories, Troublesome Things, ‘Patriotism and self-sacrifice are not the innate feelings of innocence, but carefully crafted and constructed sentiments.’

This Peter Pan example shows that the wink isn’t always singularly jocular; winks can allow adults to read ‘children’s literature’ at a more political level than children can understand. This is how a work can sometimes function as pure fun for children, but political and… well… creepy, for adults.

The Wink In Contemporary Children’s Stories

Examples above are from an earlier Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Are publishers still publishing middle grade fiction which wink at the adult reader, deliberately over the child’s head?

In picture books, I’ve heard the term ‘wink’ used differently. Picture book author Katrina Moore thinks of picture book structure like this:

- Set up

- Escalation

- Climax/Low Point

- Resolution

- Wink

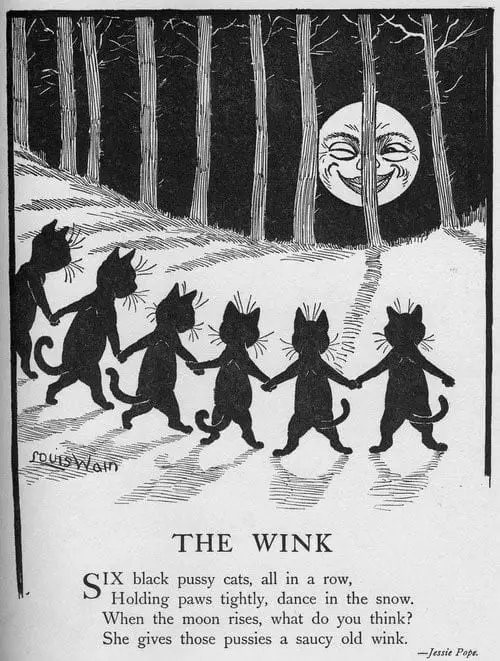

Unlike the Mark Twain Wink, the wink Moore describes is aimed squarely at the young reader. Readers of all ages are meant to understand the picture book wink, which can take various forms:

- A wink that the same story will play out again, this time with a slight variation e.g. The Pigeon Wants A Puppy by Mo Willems

- A wink that although the adults in the story don’t believe in magic, the magic is real within the veridical world of the story e.g. The Polar Express by Chris van Allsburg

The following book description describes the wink ending perfectly. The 2007 Lebanese picture book is called مل اكن اقصد (It was not my intention), written by Samar Mahfuz, illustrated by Baraj Lena Merhej:

The story of a girl who does stupid things that carry consequences. But each time she learns from her own mistakes. A glimmer in her eyes is reminiscent at the end of this album that she thinks about another stupid thing…

The World Through Picture Books

I put it to you that contemporary children’s books do not typically wink over their heads. Young readers are expected to understand all of the jokes, laughing alongside any adult co-readers, perhaps even getting more of the jokes. In my experience, kids are better than adults at picking out humorous details in an illustration. Today’s young readers are highly visually literate.

It’s no doubt possible to find modern examples of jokes which go over children’s heads, but it’s difficult to find examples from the bestseller lists. What has led to this change in storytelling culture?

Are modern children more sophisticated? I suspect so. Today’s young readers have seen a huge amount of story compared to the children of the 1950s. That difference alone, apart from other significant societal changes, sets today’s young readers apart.