“Man-Size in Marble” (1893) is a gothic short story by Edith Nesbit. You can read it at Project Gutenberg, as part of Nesbit’s Grim Tales collection. This tale is her most widely anthologised short story.

What must it be like to be ahead of one’s time? It’s happened to scientists over the years. The guy who worked out there are an infinite number of infinities ploughed a lonely furrow — none of his contemporary colleagues bought his whacky theories about that. In the end, decades later, whaddaya know, he was right.

When it comes to writers ahead of their time, a standout example is E. Nesbit. For more on why, I’ve dedicated a separate article.

In this story, Nesbit is critiquing gender essentialism of the day, in which men were seen as rational and dynamic while women were seen as sensitive and passive. She does not critique this with a simple gender inversion. As I have noticed in the past, the gender flip is not especially good as a vehicle for critique anyway.

Interestingly, Nesbit was famously scared of the dark.

I spend a bit of time on book recommendation sites and modern parents are still buying Enid Blyton. I wish someone, once in a while, would place E. Nesbit in the hands of modern kids, if we insist that classics aren’t classics unless they’re 50 to 100 years old. You’ll find Nesbit’s children’s books have aged far less terribly than everyone else’s.That’s because Nesbit was a leftie feminist. And here’s the thing about leftie feminism: What looks radical today looks sensible after a few decades, even to conservatives.

Aside from children’s literature, Nesbit wrote short stories (for adults). “Man-sized In Marble” is her best-known example, though most people who know of Nesbit probably don’t know her for her short stories at all.

THE GOTHIC TRADITION

As explained below, Nesbit chose gothic conventions to convey her ideas. What are gothic conventions, exactly? I have wondered that myself and went into it here.

‘Man-Size in Marble’’ (1893) is both a successful Gothic chiller and a more politicized investigation of the plight of the artistically ambitious New Woman under patriarchy. It posits that while Gothic’s anti-feminism during the fin de siècle (end of the [nineteenth] century) is an increasingly familiar topic of study, little attention has yet been paid to the ways in which Gothic can also serve as a means of critiquing such attitudes. Through a close reading of Nesbit’s story and a comparison with other relevant texts of the era, the essay suggests that the author’s own radicalism, often overlooked by those who stereotype her as a writer for children*, encourages her to expose the violence inherent within late nineteenth-century social systems. For Nesbit, the Gothic is the perfect instrument for such a project.

abstract of E. NESBIT’S NEW WOMAN GOTHIC by Nick Freeman

*Though it’s doubtful meant this way here, the phrasing of ‘overlooked by those who stereotype her as a writer for children’ may encourage an interpretation that, had Nesbit ONLY been a writer for children, this would have indeed been a lesser thing. This is an attitude that has plagued children’s literature since the beginning of children’s literature. In fact, children’s literature must appeal to both adults and children and is therefore one of the most difficult things to write.

- Mrs Dorman the housekeeper is a classic Gothic archetype. She’s the Cassandra figure who warns of impending doom but no one believes her. She’s the Madwoman or the Old Wife. However, in this feminist story she is more than an archetype. She is indeed old and wise with a deep store of local knowledge. She refuses the neat division between legend and history. She is presented as the inverse of a Londoner. Mrs Dorman has a symbolic name. She oversees the transmission of stories between the ancient village and its newcomers.

- Laura is the virginal character (although not literally, since she’s newly married).

- The narrator is the hero of his own story, according to him. If he wet his pants and ran away screaming, he’s not going to tell us, is he.

- The setting of the church and graveyard is a classic setting for Gothic horror.

- Your typical gothic horror includes members of the clergy. In this tale the clergy are conspicuous by their absence — the ending does not encourage us to believe there’s a God looking after us all, though that’s what Jack thinks.

- By the 1890s gothic fiction was becoming increasingly violent. This story is quietly, off-the-page violent, but shocking for its time. There are several reasons why readers were developing a higher tolerance for gore — newspapers were reporting crimes in greater detail; the library system collapsed and this led to relaxed censorship; writers of realist fiction were pushing the boundaries with stark horror; magazines wanted shorter short stories which meant writers were cramming in more content via shock value.

- The symbolism is Catholic, which makes this part of British Gothic tradition — a ‘Latinate, idolatrous and regressive world at odds with the progressive rationalism and secular statehood inaugurated by Henry VIII’s break with Rome’. (Women and the Victorian Occult).

- This story belongs to a subcategory of the gothic tale, about sinister ceremonies, anniversaries and rites. These are pagan in origin. Other examples: “Pallinghurst Barrow” and “Wolverden Tower” by Grant Allen, “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson. In film we have The Wicker Man, which ends in fire. However, Nesbit’s rites have their origins in Catholicism.

- Nesbit made use of folklore and Gothic conventions but some of it is her own invention completely.

STORYWORLD OF “MAN-SIZE IN MARBLE”

BRENZETT

“Man-size In Marble” is set in Brenzett, which today has a population of about 400. There’s not much to it. Nesbit herself lived in Kent most of her life, though she was born in what is now Greater London. When I looked Brenzett up on Wikipedia I learned that this story is one of the most famous things about it. On the map you’ll find it about halfway between Hastings and Dover.

1893

This story was published in 1893, a significant year for New Zealand women such as myself. In September 1893 New Zealand became the first self-governed nation to extend the right to vote to women. In England suffrage came much later — they needed a world war to prove women’s mettle. But Edith Nesbit would’ve been well aware of these changes on the wind.

THE NEW WOMAN

1893 was the era of the so-called “New Woman”. Even without the vote, British feminists were encouraging independence, and advised women receive an education of their own. Of course, it was only women from the middle and upper classes who could afford to take this advice. Almost all of the fertile women in England who remained unmarried in the second half of the 1800s were from the upper classes and I surmise they preferred it that way. But these women were considered useless to society (what is a woman for, if not to provide sex and children for men?) and some put forth arguments that these women should be shipped off to the colonies, where there was a wife drought. (I wonder how many women were shipped here to Australia for that reason, against their will?)

MEN ARE MEN AND WOMEN ARE WOMEN!

During the 1880s and 1890s, there was a moral panic about how they were living in ‘sexual anarchy’ (according to writer George Gissing). All the established rules about sexual identity and behaviour were felt to be breaking down. This upsets conservatives.

I believe we have entered another moral panic in the last five years or so, as trans people are finally having their moment, and as non-binary people are requesting we use their preferred pronouns.

HALLOWEEN

The Catholic All Saints tradition is now expressed in America as Halloween. All Saints Day wasn’t the only date associated with the supernatural. People used to stay up all night ‘porch-watching’. They would stay up all night in the church porch hoping to see the wraiths of all the local parishioners parade by. This would let them know who would die in the coming year. However, this wasn’t an All Saints thing to do — most people would’ve done it on St Marks Eve (April 24).

Girls were thought to have special access to these supernatural powers. They’d be able to perform acts of divination and learn who their future husbands would be. People would light bonfires. Go back far enough (into the Medieval era) and Christians thought that souls in Purgatory would be purged by the holy fire. The feast of All Saints was an attempt to relieve the ghosts stuck in Purgatory.

Protestantism rejected all this supernatural nonsense and All Saints was removed from the English church calendar in 1559. Still, all of this remained useful to writers of gothic horror.

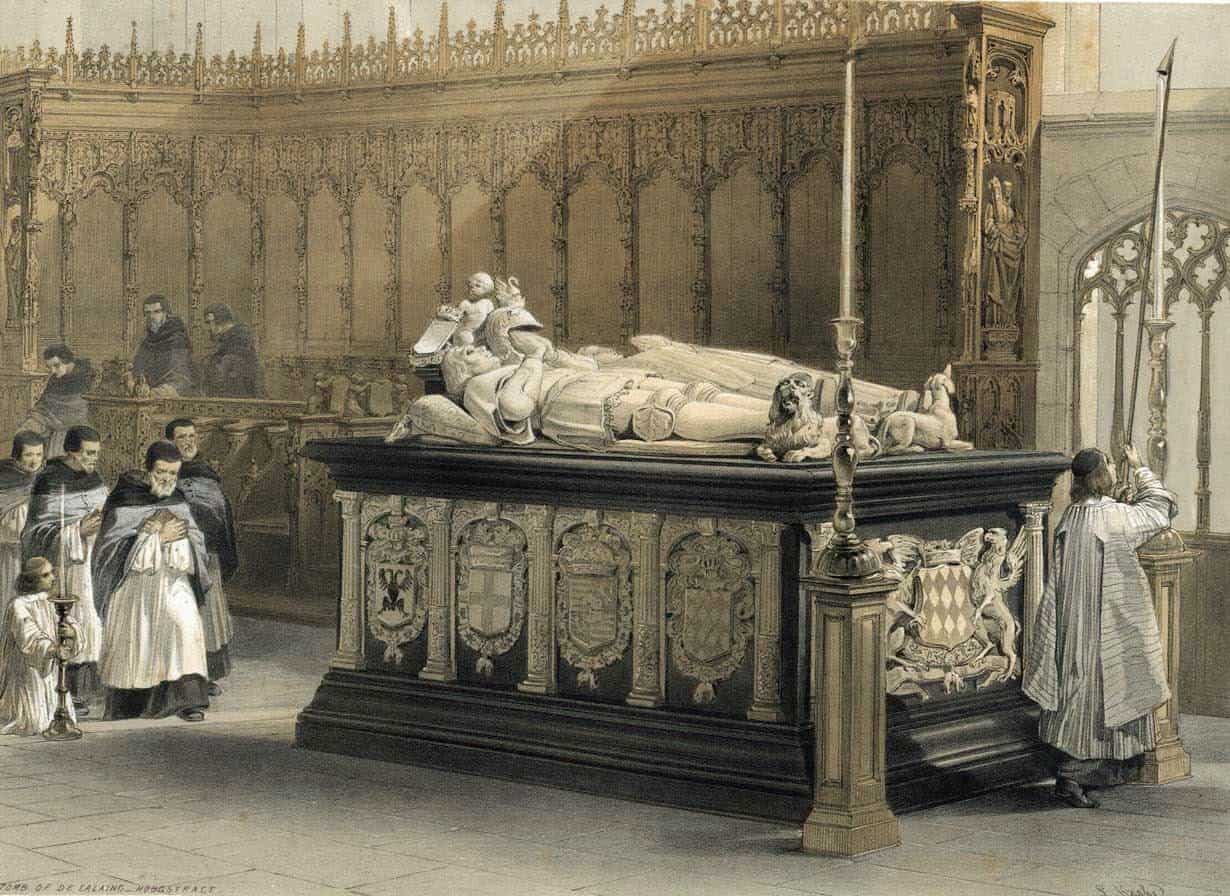

KNIGHTS IN CHURCHES

To better understand this story, it’s important to know the Catholic tradition of burying knights in important places — the closer to the altar, the more important they’d been. Supposedly.

Another impressive feature of [Saint John’s Co-Cathedral] is the collection of marble tombstones in the nave in which were buried important knights. The more important knights were placed closer to the front of the church. These tombstones, richly decorated with in-laid marble and with the coats of arms of the knight buried below as well as images relevant to that knight, often telling a story of triumph in big struggle, form a rich visual display in the church.

Wikipedia

STORY STRUCTURE OF “MAN-SIZE IN MARBLE”

The plot of “Man-size in Marble” isn’t the most interesting thing. Far from it. If this short story contained only the surface layer of the spooks in a church, I’d have called it underwhelming. Instead, the most interesting thing about this story is the characterisation of the young newly wedded man, whose attitude towards his wife comes through during his night of indescribable terror. In true Gothic convention, the story opens with a paragraph in which the narrator tells the reader the events contained within are indeed true. As you’ll see below, we are to read this ironically. This is a story critiquing Jack’s ‘rationalism’. The narration is a first person male, which fooled quite a few people at the time into thinking the author was male. This was useful.

SHORTCOMING

Man, I don’t like this Jack guy. How much of this was intended by Nesbit and how much is my modern interpretation? There’s an unanswerable question, even bearing in mind Nesbit was ahead of her own time. Jack has been described as a ‘floppy-collared aesthete’. I’m reminded of Nathaniel P from the following contemporary novel:

Waldman’s novel ‘offers a mercilessly clear view into a man’s mind as he grows tired of a worthy woman‘, which isn’t what Nesbit’s story does, but both offer insight into a man who, on the surface, is feminist but dig a little deeper and although he is not sexist, he is nonetheless constitutionally inclined to uphold the system of misogyny. (For a clear delineation between sexism and misogyny, go no further than Down Girl by Kate Manne.) Jack doesn’t treat women as adults. He treats his wife like a child by refusing to tell her what he has learned about the house from Mrs Dorman, as it might upset her. Nathaniel Piven, a thirty-something-year-old Brooklyn novelist and burgeoning public intellectual, is thoughtful yet careless, open-minded yet absurdly entitled.— The New Yorker review

Jack reminds me of Nathaniel P. because both are New Age Guys (for their era); neither are alpha males; both are aesthetes; both are writers and both appear to be in touch with their emotions. When Jack finds Laura crying he tries to comfort her with “don’t cry, or I shall have to cry too, to keep you in countenance, and then you’ll never respect your man again”. This snippet of dialogue tells us layers of things about Jack:

- He is blithely dismissing his wife’s emotions

- He makes a show of having emotions himself

- But the code of masculinity dictates he couldn’t possibly give in to them

- Because his job as husband is to be first and foremost respected by his wife.

- Ergo, this is performative empathy.

As I read the opening to “Man-size In Marble” I’m reminded of that show Escape to the Country and all those city people who go touring various country houses — oftentimes none of the houses are good enough and we learn the city folk didn’t really want to move to the country after all. Well, these two do eventually find a house to their liking, fussy as they are, and then the husband complains they don’t have any money. Next minute they’ve employed a ‘peasant woman’ to do all the housework.

‘Poor’ is such a variable concept, isn’t it? These two aren’t poor poor. They are living in ‘genteel poverty’, like the women in Sense and Sensibility. I mean, if you can afford to employ someone from a lower class to do all your drudgery work, you ain’t poor. When the peasant woman housekeeper takes off, this guy won’t believe her reasons. She tells him her niece is sick. He doesn’t buy it because the niece has always been sick. It doesn’t occur to him that sick people often get sicker — no, it’s all about him.

Jack speaks for Laura and Mrs Dorman throughout the story, refusing to take either of them seriously. He loves folklore but treats Mrs Dorman as a Victorian anthropologist might a tribal elder — perhaps here, Nesbit is satirizing the folklore “collectors” of the period such as Edward Clodd — and patronizes Laura with a pet name “Pussy”. He also persistently trivialises her art despite the fact that it seems to be their only earned income; while Laura is writing, he passes his time in sketching “wonderful cloud effects”. Whether her tales are “little magazine stories” or stories for the little magazines that were so much a feature of the 1890s’ literary scene, Jack sees them as insignificant, fit only for the “Monthly Marplot”. His disdain for “the jingling guinea” is what one would expect from an aesthete of the period, but it shows, too, a worrying inability to face up to the economic realities of his marriage.

Nick Freeman

At this point I refer you all to The Wife (both book and film), by Meg Wolitzer. Jack’s rationalism is at odds with the outlook of the story’s women: it is his adherence to it that ultimately brings about his “life’s tragedy”.

The story begins with a confession of rationalism’s limits, a frequent Gothic device as well as a rebutt fo the positivism that was making Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes so pouplar in the early 1890s. … For much of the story, howeer, he is quite happy to live by rationalist principles, signally a clear divide between himself, the seemingly superstitious female characters, and maybe, by extension, the villages as a whole: the Irish outsider, Dr Kelly, is after all the “only neighbour” with whom Jack socializes. The more intuitive Laura is less imprisoned by this gospel, though…her sensitivity is not enough to save her from an awful fate, perhaps because her attitudes to social class are less radical than Nesbit’s own. The “village people” are, she says, “awfully sheepy”, and if one won’t do a thing, one may be quite sure none of the others will”.

Nick Freeman

His wife, Laura, is the one who won’t listen to the housekeeper (according to Jack), and is very much down in the dumps about losing Mrs Dorman — this means they will have to do all the housework themselves. And by ‘they’, we do mean Laura, don’t we. “Don’t worry your pretty little head about it,” the husband tells her. “There will still be time to do art even if we have to do everything ourselves.” Meanwhile, it’s a point of pride that he’s useless around the house. He tells us he has surprised himself by doing an excellent job of washing the plates. Well, if you’ve ever seen that documentary series where they take a modern family and make them live like it’s 1900, you’ll already know this, but the loss of the housekeeper really does mean the loss of the young wife’s artistic life. The husband doesn’t realise it because he’ll be swanning around doing the bare minimum at home (a bit of polishing here and there, fixing what’s broken and so on) but the day to day drudgery of cooking, cleaning and washing will be the dawn-to-dusk job of his wife. Soon children will arrive and there will be literally no time for her to pursue her creative goals.

In short, this guy has plenty of Shortcomings. But it’s up to the reader to pick up on those, because it’s written in first person so we have no detached narrator to guide us in this direction. Would a guy from 1893 have had the same reaction as I just had?

DESIRE

At the beginning of the story, the narrator’s number one Desire is to find a nice country house for himself and his new wife so they can lead an artistic country life together.

OPPONENT

They find themselves a housekeeper but it goes tits up when she leaves. Now he will have less time to pursue his creative goals. The Minotaur Opposition is of course the spooks in the church.

Faced with Mrs Dorman’s absence, Laura worries that “I shall have to cook the dinners and wash up all the hateful, greasy plates … and we shall never have any time for [creative] work.”. The statues will not stand for her transgressions, and a collision between flesh and blood and calcified tradition is inevitable. In this respect, it is notable that they no longer have names, for they are less individuals in themselves than representatives of a reactionary brutality that destroys those who oppose it.[…] Quiescent for most of the time, the forces embodied by the stone knights have not been wholly vanquished by those of progress and modernity and are yet capable of wreaking havoc when roused.

Nick Freeman

If that last paragraph isn’t a perfect description of misogyny, I don’t know what is. Nesbit’s Stone Knights = misogyny.

Sexism is the ideology that supports patriarchal social relations, but misogyny enforces it when there’s a threat of that system going away. — Kate Manne

PLAN

He will try to persuade their excellent housekeeper to come back. He will also wheedle out of her why it is she has left, presumably so he can tell her that her reasons for leaving are not adequate. He doesn’t exactly set out to solve the mystery of What Spooked The Housekeeper, but he does happen to wander into the church at the exact time on All Saint’s that the statues are meant to come to life. (Coincidence works fine in gothic fiction, which is inherently melodramatic.)

BIG STRUGGLE

While the narrator is chatting to the local blokes about spooks his wife is busy getting murdered. This happens off-the-page. Though at first pretty comical, consider this a symbolic rape and the finger as phallus. Not so comical now. No wonder that was left off the page. Writers are often advised to put the Battle on the page, otherwise the reader feels cheated. A lot of build-up over nothing. Bear in mind that this story is a Gothic ghost story in the same way that Alice Munro’s “The Love Of A Good Woman” is a murder mystery — i.e., not at all. Readers expecting genre fiction may be disappointed. Why did Nesbit choose the husband as narrator, which meant he wouldn’t be there to see his wife get murdered? Well, first, what we can’t see is indeed more scary. So there’s that. But also, this isn’t about the spooky walking statues at all. It’s about the young husband and his patriarchal attitude towards his wife.

ANAGNORISIS

In her ghost stories Nesbit uses the supernatural as a catalyst to precipitate an emotional crisis. This technique achieved criticism of Victorian proprieties.

Nesbit has used Catholic iconography to critique traditions of divination. After we learn she is dead we realise Laura was not protected by all those candles at all. She is ‘wedded’ to the stone knights, not to her mortal husband. Nesbit’s marble knights were once men, part of a Roman Catholic tradition which allowed their wealthy relatives to buy them a place beside the altar, even though the knights had done terrible things (‘deeds’) in their lifetimes. Of course, they’re continuing to do terrible things beyond the grave. They have no place beside the altar. Nesbit is critiquing the practice. And if we haven’t realised it by now, we know that if Jack had treated his wife as a fully-functioning adult and warned her of impending doom, Laura might still be alive.

NEW SITUATION

The ending has been described by David Stuart Davies as “cruel and unhappy”. Unlike more straight-up gothic horrors, there’s no suggestion that the characters are being protected by Providence.

EXTRAPOLATION

I extrapolate that this guy won’t be getting his housekeeper back. I guess he’ll leave the area and find another wife, and he’ll never be quite the same again. If the young woman was killed, can this be a feminist story? The question has been asked. I argue that it can because, as I keep saying, subversion works better than inversion (in which ‘inversion’ would result in an ending in which the vulnerable maiden toughens up and defeats her opponents).

“Man-Size In Marble” is instead an example of subversion, but not at a plot level — at a metaphorical level. Nesbit kills Laura not to punish her, but to demonstrate the latent violent inherent in the sexual politics of the period. Many New Women are confronted by representatives of the patriarchal order, but the encounter is usually staged in solidly realist surroundings like those of Gissing’s The Odd Women (1893). By injecting Gothic fantasy into what seems at first an unexceptional tale of newly wedded bliss, Nesbit is able to provide both the shock expected of the genre, especially in short stories, and imbue her fiction with an underlying sense of ideological dissatisfaction.

Nick Freeman

FURTHER READING

Another short story which utilises trees and what has been called ‘feminist tree politics’ is “The Name-Tree” by Mary Webb.