In the early 1800s, the Grimm Brothers collected a fairy tale called “The Old Woman In The Woods” and included it for publication in Household Tales. Is Shirley Jackson’s “The Man In The Woods” a riff on that, or something different altogether?

(Find Jackson’s story collected in Dark Tales.)

I’ll be arguing that “The Man in the Woods” is an overt but subtle feminist commentary on the ‘nature’ of things — men are the heads of households, women belong in the kitchen (metonym for domesticity and exclusion from public life), and all men must tacitly accept this gender hierarchy. Moreover, no woman (or femme) is exempt from the gendered hierarchy; it affects ‘strong’ women as much as it affects the coquettish ones.

Be honest: As you read this story yourself, were you outraged at Christopher’s response when he learned the women who cooked a delicious meal for him were required to sleep on the kitchen floor? Were you irritated that Christopher instead accepted the way of things out this way, and took a walk around the patriarch’s garden, commenting on the roses? Or did you, like Christopher, accept this homely set-up as the ‘natural way of things’?

Fortunately for us, Shirley Jackson gives feminist readers a wish fulfilment fantasy. By accepting ‘the natural way of things’, Christopher the young patriarch in training is about to become one with nature himself.

This post also delves a little into the meaning of ‘objectification’, since Christopher is shown to be doing this to the women of the house, and proposes a replacement theory for objectification as suggested by Julia Serano.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE OLD WOMAN IN THE WOODS” CLASSIC FAIRYTALE

Let’s take a look at the allusory tale. (Is it really an allusion?) I believe it is. In this variety of household tales, one character saves another from permanent entrapment, which is exactly what Christopher does not do. (If he had tried to release the women of the house from their domestic imprisonment, he would probably have saved himself at the same time.)

- A peasant girl is travelling through the woods with her master and mistress when robbers appear and murder everyone except the girl.

- Traumatised, she eventually slumps helplessly on the ground, prays, and resolves to die.

- A white dove appears, gives her a key and leads her to a tree. The tree opens. She finds bread and milk. Next, a comfortable mattress to sleep on. This tree closet keeps giving and giving. She doesn’t want to leave the forest now. She has everything she needs. Her new tree-given clothes are even better than royal clothes.

- But one day the dove requires something in return. She must find an old woman who lives in a cottage in the woods, sneak past into her room full of rings and find the only simple ring among the many jewels.

- There’s a bit of a kerfuffle inside the house, but the old woman is old, the young woman is young, so the peasant girl is able to retrieve the only simple ring in the house, which happens to be held in the beak of a caged bird held in a cage by the old woman.

- Who is a witch, of course. Long ago she put a curse on a prince and turned him into a tree, though he’s allowed to be a dove for two hours per day.

- When the peasant girl returns to the tree with her ring, the tree grows arms, puts its branch-arms around her and reveals himself as a very eligible bachelor.

- Next, all his servants and horses morph back into their original forms.

- Peasant girl and prince marry, then live happily ever after.

“The Old Woman In The Wood” isn’t really about an old woman at all, but is a rags-to-riches story of a peasant girl who becomes a princess. If anyone’s ‘in the wood’, it’s the prince.

What I want to know is, the backstory and future prospects of the witch’s captured bird — the one who made sure to give the girl the simple ring in its beak.

Also, why not enter the cottage at night when the witch is asleep? (In other versions, she waits until the witch leaves the house.)

This fairytale is just one of many ancient stories about characters who get lost in the deep, dark woods, meet with magic and must defeat a creepy old person who lives in a cottage and hates the world or wants something from her in return for basic sustenance.

LOST-IN-THE-WOODS TALES

To name but a few of the enduring ones:

Hansel and Gretel

This one contains all the good stuff: terrible parents, cannibalism, an edible house. No wonder it’s found endurance. You were very likely exposed to this story as a kid.

Jorinde (she/her) and Joringel (he/him)

If you’re German you likely know this one, but if you’re not German, chances are you don’t. “Jorinde and Joringel” is the German title collected by the Brothers Grimm. The story is known in many English translations as “Jorinda and Jorindel.”

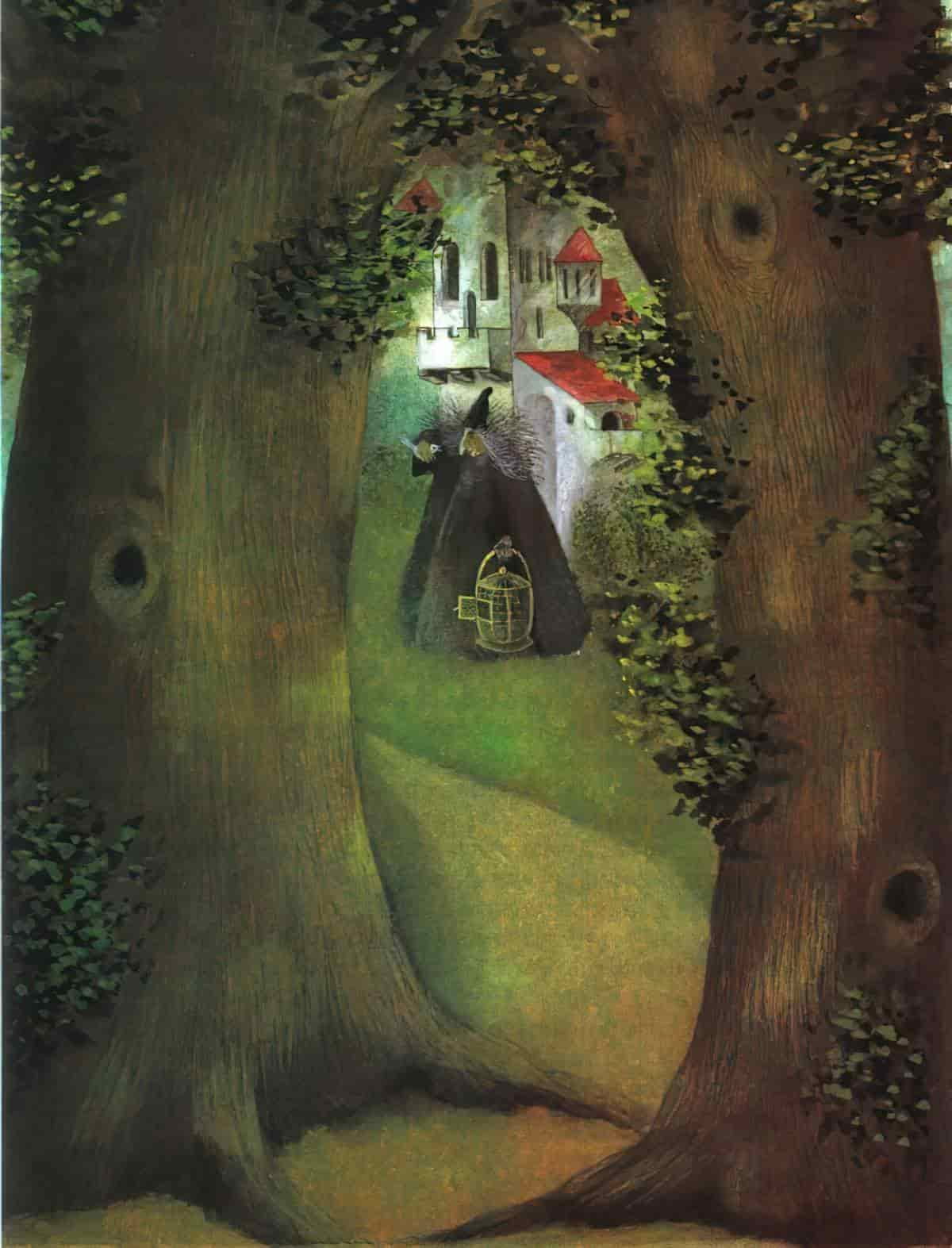

Again we’ve got the witch in the woods. Is she witch or fairy? That part’s not clear. (Fairies can fall anywhere on the morality spectrum anyhow.) She lives in a castle in the forest. You would, wouldn’t you, if you can shapeshift? I mean, if you can transmogrify your own body, you’d turn your hut into prime real estate, right? With no neighbours? Plenty of privacy? With a jacuzzi, tennis court… Strangely, though, she hunts her own food.

She likes bird meat, I mean birds, pretty birds for their plumage, I mean bird meat. Wild pretty bird meat. Although humans have been hunting and gathering for millennia already, suddenly when a solitary old woman does it, somehow it’s creepy now. It’s not like she eats humans.

Wait, but does she? Does it count if you turn a human into bird meat first? Two young lovers are going for “a walk” in the forest. (This tale was clearly an Urban Legend of long ago, reminiscent of Have Sex And Die stories like “The Hook”.) This witch turns the girl into a nightingale. Joringel gets petrified. I guess the old lady doesn’t eat nightingales though because she sets the birdy version of Jorinde free, cackling about how she’ll never see her lover again, ahhahaaa!

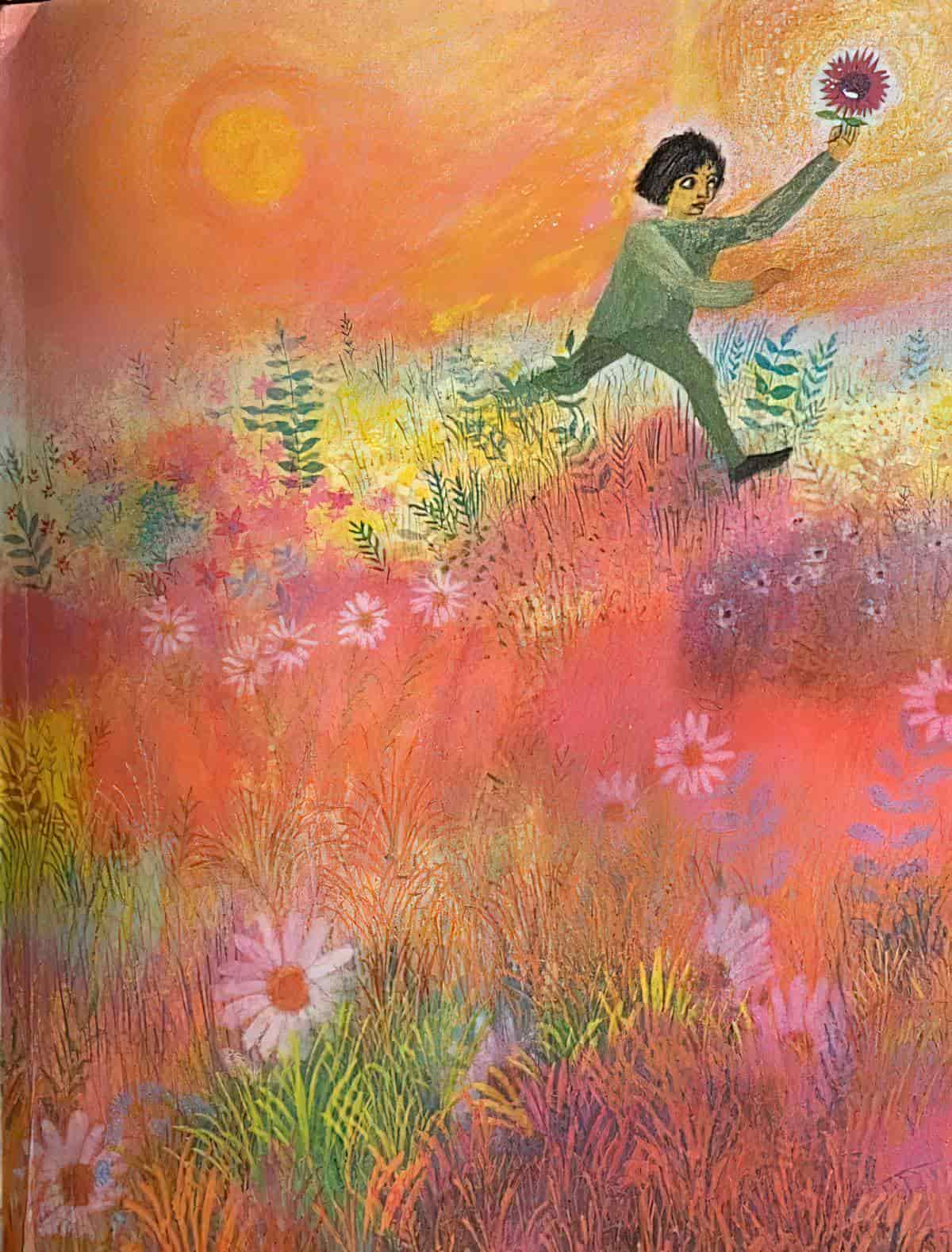

But Joringel still has consciousness. (I hope he doesn’t get itches. That would be mighty annoying to get itches if you’re made of stone.) He can only but dream. One night he dreams of a flower which is the key to breaking the witch’s spell. He’s not petrified all the time, and is able to creep around looking for this white flower.

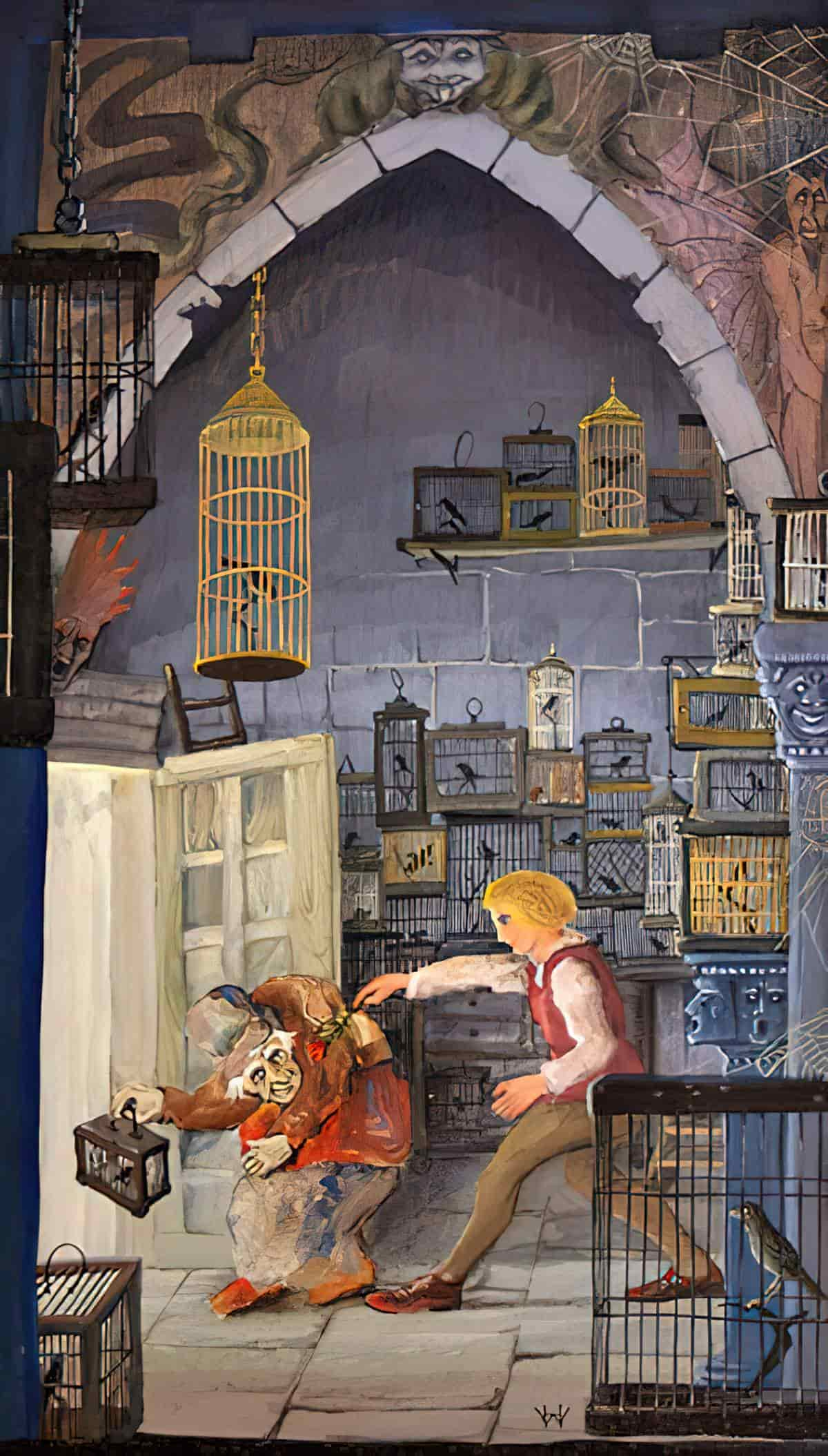

He returns to the castle where the witch is feeding her caged birds. With him holding that flower, the witch is unable to put any curses on him. He realises a bird in one of the cages is actually Jorinde. He touches her with the flower and she turns back into a woman (hopefully after she is let out of the cage, otherwise that could hurt). Then he turns all the other birds back into women.

We don’t know what happens next, but I wonder if this will be some kind of bride plus many concubines arrangement. (Seven thousand concubines, to be precise. That’s how many birds there were, and a few hundred of them nightingales.)

And I want to know more about the witch. Why did she cage only beautiful young women? Is her sexual/romantic orientation ‘birds’, but only beautiful young women can turn into beautiful birds? (This isn’t even how birds work — the most beautiful birds tend to be male, for show-off purposes.) Oh well, human gender was only conceptualised in the mid 20th century. (How The Clinic Made Gender by Sandra Eder, 2022.)

The Hut In The Wood/Forest

When people go deep into the woods, horrible things ensue. They are inhabited by inbred hillbillies, barbarian tribes, psychopathic killers, wicked fairy folk, monsters, and dangerous animals of every sort. Malevolent eyes gaze from every shadow. Perhaps even the trees themselves attack them. The woods could be cursed. There are strange noises in both the day and the night. People disappear. People go insane.

Don’t Go In The Woods, TV Tropes

This time, the lost girl’s father is a woodcutter. He tells her to bring him lunch so he doesn’t have to walk all the way home for it, but unfortunately the girl loses her way. She does find an old grandpa who talks to animals living in a creepy, two-storied house. In return for cooking him a feed he agrees to let her sleep in an upstairs bed, but the creepy old mofo follows her upstairs, opens a trapdoor (presumably built especially for this purpose) and drops her into his cellar as punishment for… getting lost, I guess? She should’ve poisoned his dinner.

Anyway, the woodcutter actually has two daughters and, wouldn’t you know it, the same thing happens to her. The very next day! You’d think they’d all be out looking for the eldest, missing daughter, wouldn’t you? But no, she must be expendable. (She’s probably ugly?) Nope, there are three daughters because of course there are.

The third daughter won’t suffer the same fate. That’s not how fairytales work. Twice establishes a pattern, now it must be broken. Sure enough, the youngest daughter does not get dropped by trapdoor into the cellar. Instead she wakes at midnight to the sound of the entire house tearing apart and is transported to a luxurious palace.

Why? Because she was especially nice to his animals. The creepy old man is actually a (still creepy) young prince who had been cursed by a witch. (Methinks he fully deserved it.) Apparently, only a beautiful young woman who is kind to animals could break the spell. But although the older sisters had cooked for him in return for a bed, they hadn’t been sufficiently kind to his animals, so he made them char-burner servants for life, or at least until they had learned to be kind to animals.

(Kindness is for femmes, of course. I deduce the witch actually put a curse on the horrible young prince hoping he himself would learn some kindness, but the extraordinary level of kindness demonstrated by the youngest daughter passing by broke it on his behalf.)

FEATURES OF LOST-IN-THE-WOODS FAIRYTALES

In these stories it often happens that some kind of bewitching has happened to royalty, and only a beautiful, marriageable young woman can break the curse.

The witch may look like a harmless little old lady but she has secret, invisible powers which make her dangerous. This thinking is what led to the Witch Craze of the Middle Ages, of course, when people really did believe every village and hamlet had a witch. The witches were the most disposable members of society — elderly, barren women, unable to work.

The forest stands in for the subconscious. That’s why forests are so hopelessly lonely. Once you turn inwards, you’re alone with yourself. You confront your deepest fears (and desires). A return to civilisation is a return to interactive society.

Vladamir Propp listed 31 plot points of all fairytales (though not all fairy tales contain all 31 plot points).

Note that the heroine of a fairy tale is not simply the femme presenting equivalent of a hero. A heroine is simply ‘good’ (passive) whereas a hero is expected to fight for a cause. Another way of categorising the main characters of fairy tales: Seekers versus Victim-Heroes. (Seekers are those young men who leave home to seek their fortune. Victim-heroes are peasant girls and bad things happen when she leaves the house.)

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE MAN IN THE WOODS” BY SHIRLEY JACKSON

STEP ONE: GENDER INVERSION

The first inversive thing: Shirley Jackson has taken a man and got him lost in the woods. Not a nubile young woman at all. There’s no backstory to this guy. He appears on stage in statu nascendi. Is he in a fugue state? (Is that even a thing? I learned it off Breaking Bad.) In any case, we can read this Lost In The Forest story as a trip into his own subconscious.

Wearily, moving his feet because he had nothing else to do, Christopher went on down the road, hating the trees that moved slowly against his progress, hating the dust beneath his feet, hating the sky, hating this road, all roads, everywhere.

Shirley Jackson, the opening sentence to “The Man in the Woods”

This guy’s on a Fatal Forced March.

All we are told is that he has come into his subconscious “at a crossroads”, which of course symbolises some kind of moral dilemma, probably with two choices as bad as each other.

There’s a cat. Where there’s a shadowy cat, we can expect a witch to appear.

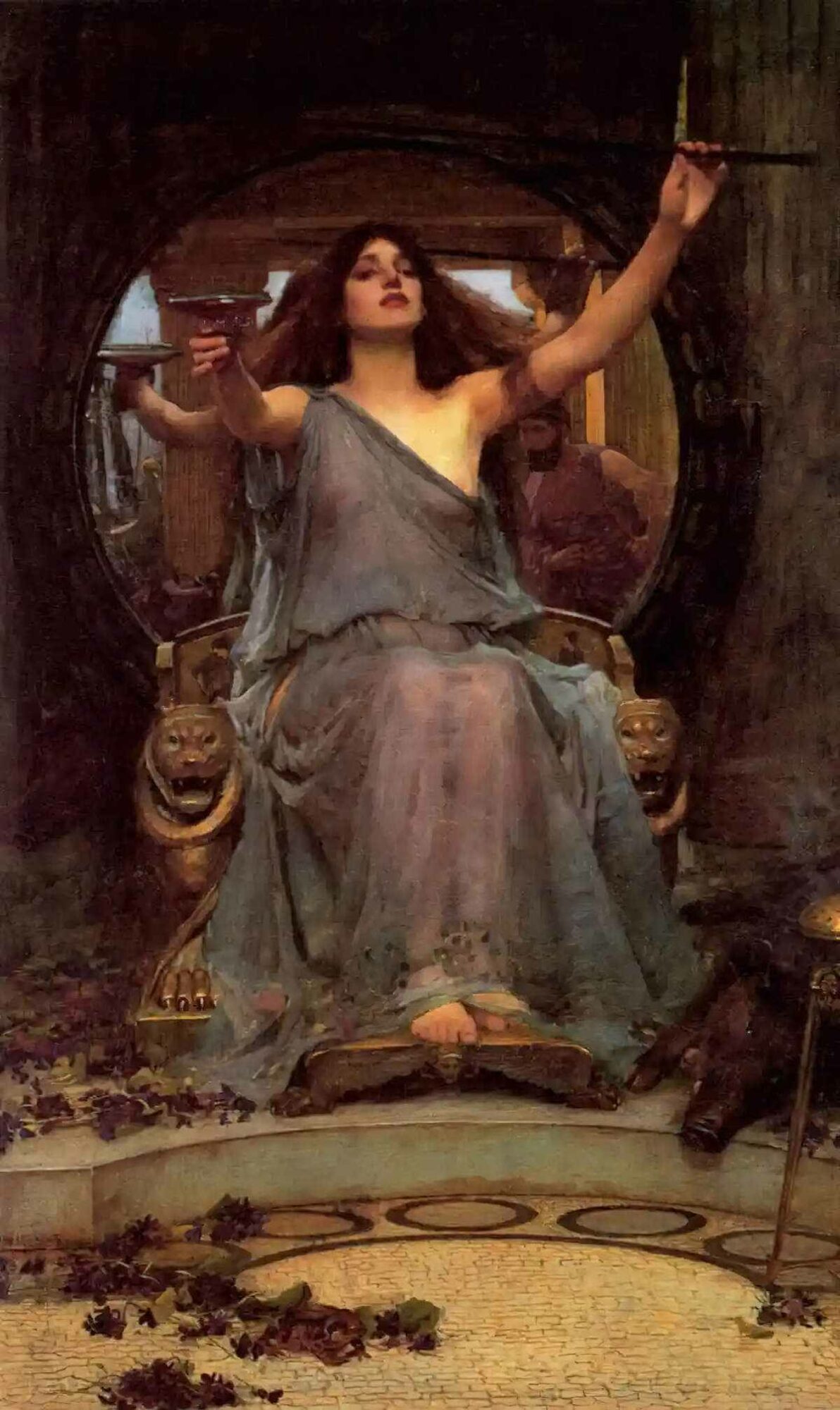

Sure enough, he happens upon a cottage. The witch inside is not some generic old woman but named as Circe.

WHO IS THE ORIGINAL CIRCE?

Circe is the first great witch in literature, described by Homer as “goddess or girl, we couldn’t tell” and when she’s first seen by Odysseus’ men she seems a sweet young weaver, weaving ‘ambrosial fabric sheer and bright,/ by that craft known to the goddesses of heaven.” Before her loom she sings ‘a chill, sweet song’.

Circe doesn’t seem to be a witch at all. Yet she is accused of: enthralling men, turning them into swine and making them impotent (sexually and otherwise).

But Jackson has not just inverted the gender of the lost character for the sake of it. Inversion does not equal subversion, but this tale is subversive as well. The more I read of Jackson’s tales, the more I conclude she’s as subversive as the great Angela Carter. But unlike Carter, Jackson doesn’t tend to be hailed as a feminist writer. My take: Jackson was simply more subtle about it.

OBJECTIFICATION, MY DUDE? EVEN WHEN YOU’RE LOST IN THE WOODS?

First, let’s talk about objectification. Actually, I’ve just read Sexed Up by Julia Serano, so I don’t want to talk about ‘objectification’ anymore. The problem with that word: There’s nothing wrong with objectification when we are objectified by sexual partners who know us also as whole people. Serano advocates for a replacement: the stigma model of sexualization (an evolution of research by Erving Goffman).

The stigma model of sexualization readily accommodates those sorts of scenarios [consensual objectification within a sexual setting], as it is understood that stigmas are simply social meanings that some people subscribe to while others do not.

Sexed Up, Julia Serano

Serano explains how this applies to trans women in particular, then how some feminists have used the objectification argument to ban pornography:

Anti-pornography feminists seem to rely on the attraction/objectification model, in which objectification is viewed as wholly negative because it dehumanizes women more generally. In contrast, sex-positive feminists seem to be working primarily from the stigma model of sexualization (even if they do not explicitly call it by this name), which explains why they place so much emphasis on destigmatizing women’s sexualities and desires provided that they occur consensually.

Sexed Up, Julia Serano

Serano also prefers the stigma model of sexualisation over ‘objectification’ because it is more encompassing. (When a man is called a pussy c*cksucker, this is him being sexualized, meaning reduced to his sexual parts. I would add that even when men are sexualized, femmes are always implicated because a man isn’t easily sexualized without invoking imaginatively female body parts and acts, as evinced by Serano’s examples.)

What has all this to do with Shirley Jackson’s Lost-In-The-Woods fairytale mash-up?

THE MALE GAZE

I think there’s a feminist reason why Jackson has got a man lost in the woods then made him encounter a (so-called) witch, and also another (strangely imperturbable) man.

When the woman in the cottage opens the door, completely out of habit, Christopher sizes her up, gender-wise and sexually. (Julia Serano also talks about that.) Maybe the woman is doing the same to him, except it seems more likely she is sussing him out for danger:

The woman stood back and looked for a minute at Christopher, her eyes searching and wide; he looked back at her and saw that she was young, not so young as he would have liked, but too young, seemingly, to be living in the heart of a forest.

Shirley Jackson, “The Man In The Woods”

Shirley Jackson doesn’t explain what is meant by ‘not so young as he would have liked’, and we don’t know the age of Christopher. (For all we know at this point, Christopher is a teenage boy and “The Man in the Woods” is the man who lives in the cottage.) Jackson just lets that one hang for now, though we learn later that he’s in college, or was.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE LIGHT

Christopher continues sizing her up. She might look older if the light were better. Next, his eyes travel down her body. Shirley Jackson describes Circe, basically, as she appears in famous paintings. (Obviously, John William Waterhouse has fully sexualised Circe — tamed her for our consumption — by dressing her in a sheer green dress, one nipple exposed as if by accident.) Turns out this woman is actually called ‘Phyllis’, which has a different ring to it now than when the story was written. (It’s now an ‘old lady’ name.)

For the purposes of Shirley Jackson’s story, Phyllis is surely an allusion to the daughter of Sithon, Thracian king. (I mean, she has used an allusion to “The Odyssey“?)

Phyllis is a tragic figure who suicides by hanging when she realises a man, Demophon, won't be coming home for her. But in another version her demise is a bit different. It's Demophon who dies. She's given him a casket, which he's only supposed to open if he's given up hope of ever returning to her. Horrified by whatever's inside, he rides his horse at such great speed that the horse can't manage the pace. The horse stumbles. Demophon falls on his own sword in a terrible accident. Either way, the story's not great for Phyllis.

Here’s what I think: Like Penelope in “The Odyssey”, Phyllis has to stay at home. She doesn’t get her own mythic journey because she’s not allowed out. Instead, only the men in her world get to leave the house. She spends her entire life pining after them.

But as we will see in Christopher’s case, a mythic journey into the woods doesn’t necessarily involve a character arc. In fact, it would seem to Shirley Jackson (writing this in the mid 20th century) that no matter what happens, it’s two steps forward, one step back for women, and men are no help at all. It’s a constant battle for feminists.

THE TWO TYPES OF WITCHES

Here’s the thing about witch archetypes: They’re either young, nubile, sexually alluring tricksters or they’re undesirable, invisibilized old hags. Those are the two bins we dump them (women) into. Actually, here’s the thing about any scary, powerful femme-coded supernatural character: All of them are tamed in story via sexualisation. The siren is an excellent example. Sirens are terrifying big black birds which kill sailors. How to tame them? Reimagine them for your own sexual pleasure. Same deal with witches.

I’m certain Shirley Jackson was aware of this bifurcation of women, because this Christopher guy she created has turned up on Circe’s doorstep and desperately tries to work out whether he needs to dump her into the sexy bin or the hag bin. How old is this chick, exactly? If only the lighting were better! Notice how grateful he is for the light — not just because light equals comfort and food but because it also illuminates what category of woman he might be dealing with here!

Light or no light, he’s taken his chances. He’s already inside by the time firelight illuminates the situation. This femme is young, ‘though not as young as he would have liked’, so he comes inside hoping to take refuge for the night.

Another witch stands by the stove (Circe).

SUBMISSIVE PHYLLIS

When speaking to Christopher, Phyllis does this thing with her eyes. I may never have noticed had I not recently read this by trans non-binary femme, Kate Bornstein:

As part of learning to pass as a woman, I was taught to avoid eye contact when walking down the street; that looking someone in the eye was a male cue. Nowadays, sometimes I’ll look away, and sometimes I’ll look someone in the eyes — it’s a behavior pattern that’s more fun to play with than to follow rigidly. A femme cue (not “woman,” but “femme”) is to meet someone’s eyes (usually a butch), glance quickly away, then slowly look back into the butch’s eyes and hold that gaze: great, hot fun, that one! None of this is written down or even particularly enforceable, but in my part of the world, all of this was required for membership in the gender woman. (Of interest is that these are also universal cues of submission.)

Kate Bornstein, Gender Outlaw p33

The thing Phyllis does with her eyes:

When she spoke she looked away from Christopher, turning her overlarge eyes on him again only when she stopped speaking.

Shirley Jackson, “The Man in the Woods”

CIRCE’S STRENGTH

Whereas Phyllis is feminine and bashful, Circe is unusually strong. She carries this big, heavy pot from the stove.

Significantly, Circe goes by two names. Her powerful name (which she says she prefers) and the diminutive Aunt Cissy. The diminutive domesticates her, renders her weak and homely, charitable and motherly. This is why Christopher is surprised by her strength. (Take the hint, man. Leave now.) Two names also suggests duplicity (in stories).

But three kerosene lamps on the mantle suggest three inhabitants of the house. Sure enough, Christopher is not the only man in this house. After some emphasis on the cat (called Grimalkin — we now wonder if the cat led/lured Christopher here), Oakes appears — an old man, cult-leader type with a resonant voice of authority. He’s clearly the boss of the ladies, even though they all wear the same green robe with no shoes.

OAKES AND OAK TREES

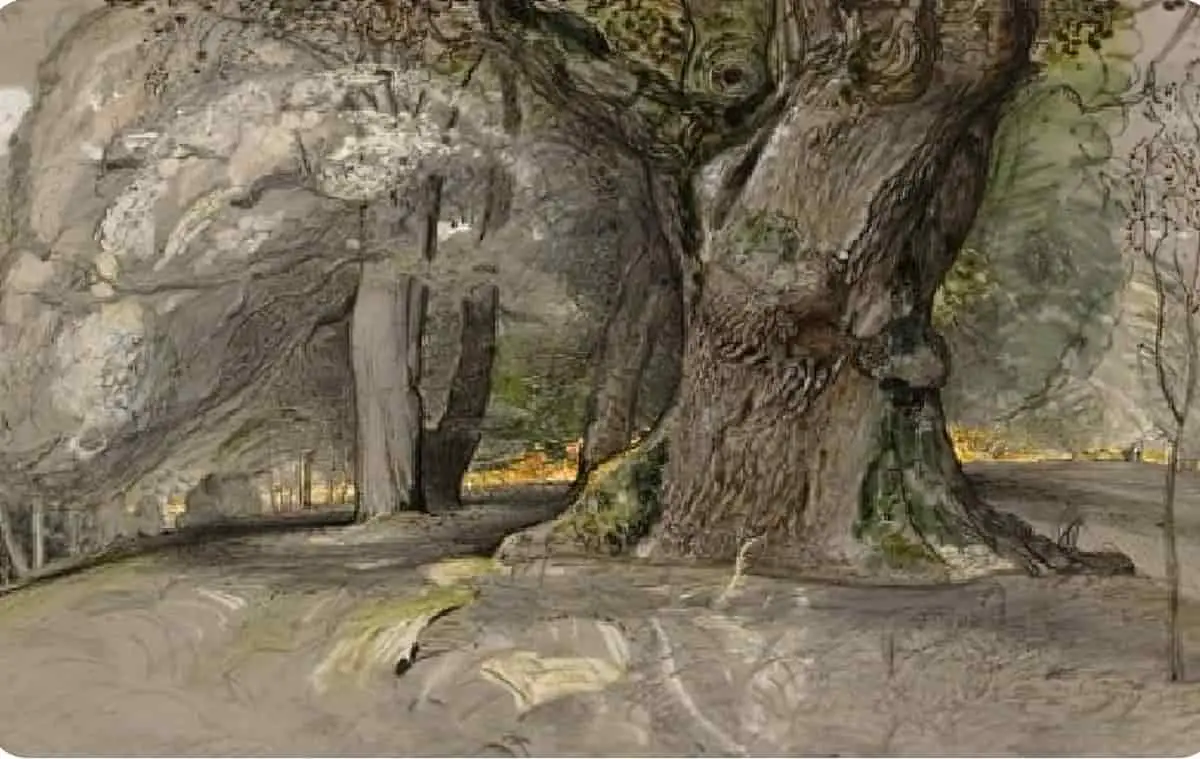

Fittingly, for someone so close to the trees — metaphorically and literally — he’s called ‘Oakes’. (Oak trees live a very long time — sometimes over 1,000 years. It is said that an oak spends 300 years growing, 300 years living and 300 years in slow decline.)

Although oak trees live a long time, there may be some symbolic connection to death, since coffins (in the West) are traditionally made of hard wood such as oak. At times the poorest people have been forbidden to make use of coffins when they die, saving such precious wood for the wealthy. (In China coffins might be made of fine wood or cypress, and even more costly.)

Humans tend to make a cult of trees. Many ancient traditions posit the existence of a primal tree that embodies eternal life. Reverence surrounds the Bodhi Tree, in Bodh Gaya, India; the Cypress of Abarkhuh, in Iran; the Hibakujumoku trees, in Hiroshima, which withstood the atomic blast. There are trees of life, and trees of death. In Schubert’s song “Der Lindenbaum,” from the death-haunted cycle “Winterreise,” a linden tree calls to a disconsolate wanderer, “Come to me, friend, / Here you will find rest.” Thomas Mann makes much of that song in “The Magic Mountain,” finding it symbolic of a civilization hurtling toward its own destruction.

article by Alex Ross The Bristlecones Speak Learning from the World’s Oldest Trees In the January 20, 2020 issue of The New Yorker

Whichever way we parse it, our guy Christopher is coming close to death. (As happens in pretty much every Odyssean mythically structured story over the last 3,000 years.)

Notice how the old man ‘bows his head’. The way Jackson describes his posture, she might be personifying an actual oak tree. “Yes, all those trees,” he says, meaningfully. Hopefully readers have picked up the comparison even though hapless Christopher clearly hasn’t.

The man-as-tree thing comes directly from “The Old Woman In The Woods,” as you may recall, though Jackson is doing something different with it.

This Oakes fellow is steady, too steady in his dealings with his guest. “That need not concern you,” he says when describing where the onions come from (down near the river, fyi). None of this concerns Christopher.

But here’s how food works in fairy tales: Once the visitor eats from this world, he’s done for. The world becomes part of him. (Handy traveller’s tip: Never accept food from fairies until you know for sure they’re goodies.) I’m not getting a ‘goodies’ vibe here, are you?

CAT FIGHT

The house tabby fights with the black cat who led Christopher here, which is the beginning of the battle sequence of the story.

CHRISTOPHER SPENDS THE NIGHT

He should probably twig to the fact he was in a story with tree people when he found his mattress stuffed with leaves? (See what I did there?)

MAN-TO-MAN-CHAT

The following morning, Oakes is hardly talking but refers to the women as his ‘handmaidens’. They’re not allowed out of the kitchen unless they get his go-ahead.

Outside, Christopher makes smalltalk about the roses, which he doesn’t seem to realise are alive, or at least ‘alive’ so far as Oakes is concerned.

CHRISTOPHER’S ABOUT TO GET TRUSSED AND COOKED

The handmaidens are preparing a huge feast but are pretty cagey about what it’s for. Christopher’s getting antsy. Then a trussed pig comes out. Everyone knows that, if cooked, humans taste like pork, right? I mean, I can’t tell you how I know that, but I must have got it from pop culture. (I looked it up so you don’t have to: Yes, it tastes like pork but looks more like beef.)

In the final three paragraphs, point of view moves away from Christopher’s close third person to omniscience. As the narrative camera rises, we see the handmaidens and Oakes conspire to kill Christopher down by the river, and we’ve had enough clues to realise he’ll be fed to the trees… I think? Roses need fertilizer, right?

A regular, generous application of well rotted animal manure or compost and blood and bone are perfect for roses.

Treloar Roses

If you come across roses in a Shirley Jackson story, beware. Here’s another rosy horror from the same Dark Tales collection: “The Possibility of Evil“.

RESONANCE

Do you think this short story says anything? About protecting trees? About hapless young men who see and participate in gender oppression, do nothing about it except to join in and enjoy the spoils of women-relegated-to-the-kitchen, then die a grizzly death, killed by an archetypal patriarch?

I suspect “The Man in the Woods” is mainly cathartic. Christopher may go into the metaphorical woods, but he doesn’t take the opportunity to investigate his own relationship to the patriarchy. In feminist fiction, at least, such men get their just desserts.

By another reading, we might understand the trees to mean that this (patriarchy) is indeed the natural order of things and nothing can be done about it, because the social world (just like the natural world deep in the woods) has evolved over millennia.

In a poem about elm trees, Louise Gluck says this:

Elms by Louise Gluck All day I tried to distinguish need from desire. Now, in the dark, I feel only bitter sadness for us, the builders, the planers of wood, because I have been looking steadily at these elms and seen the process that creates the writhing, stationery tree is torment, and have understood it will make no forms but twisted forms.