Before we had clocks, humans paid more attention to the sky and environment. Read older classics such as the novels of Thomas Hardy and notice how characters make use of all their senses once the sun goes down. They couldn’t simply flick on a light. Even though candles have long been available, they were expensive. My own Northern Irish peasant ancestors were well-accustomed to darkness.

I know this partly because an optometrist told me I have large pupils which don’t dilate down all that well. Especially when young, I had no trouble navigating the dark. Like many child readers, I was constantly told to turn on a light.

Clocks (and later, home lighting) changed our entire mode of being:

So kind of 13th, 14th century, mechanical clocks start diffusing and they start in Italy, but they rapidly go from city to city and towers are trying to one off other towers and they would ring bells. And it led to the city kind of literally running like clockwork, like they ring the bell and everybody wakes up and then has breakfast and then there’s the lunch bell and so the city begins to run like clockwork. But the clock doesn’t diffuse into the Middle East and other cultures didn’t seem to have the immense interest in getting a clock the way the Europeans do.

Joe Henrich on the Preposterous Universe podcast

Industrialisation also put an end to genuine beliefs about certain magical times of day.

THE BLUE HOUR

The blue hour is mostly a photography and art concept. Especially on older cameras, photographs taken at the ends of the day turn out better than when taken under bright sunlight. The blue hour comes from French l’heure bleue and refers to the period of twilight when the sun dips below the horizon, causing residual sunlight to cast a blue light over the landscape.

Photographers love it because the light is soft enough to emphasise the most of the dark areas of the scene but doesn’t require any additional light source. Landscapes look magnificent.

“Blue Hour” is an informal rather than a scientific term. It happens at both ends of the day. But it doesn’t last long. That’s what makes it precious. If you want to catch it in the morning, get up 30 minutes before sunrise. If you want to notice it in the evening, blue “hour” happens about 10 to 15 minutes after the sun has set.

Although the term “blue hour” suggests a different shade of blue, it can also refer to the various colours which appear during these minutes. “Blue” hour might actually be yellow, red or orange. This all depends on where you are, the quality of the air and the time of year.

In the illustration below, Tom Lovell takes the concept of “blue hour” and flips it. For parents of young children, there’s nothing magical about the late afternoon. It’s a time when patience runs out and kids run wild before settling down for the evening.

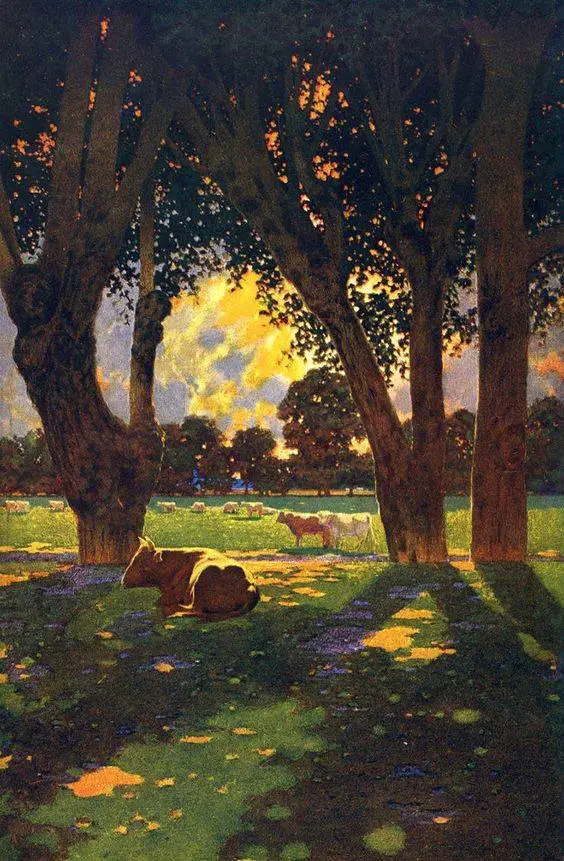

THE MAGIC / ENCHANTED / GOLDEN HOUR

Like “blue hour”, “golden hour” is a term used by photographers. You might also hear “magic hour”, especially among cinematographers.

You might also hear “the gloaming” or “divine light” to describe this diffusion of sunlight.

Why else does this time of day feel so special, apart from the majestic colours of the sky? Because this is a liminal time of night, marking the transition between light and dark.

I’ve collected some of my favourite paintings and illustrations of sunlight and sunrise here.

THE MAGICAL HOURS UNDER CLOAK OF DARKNESS

Toys Come Alive At Night

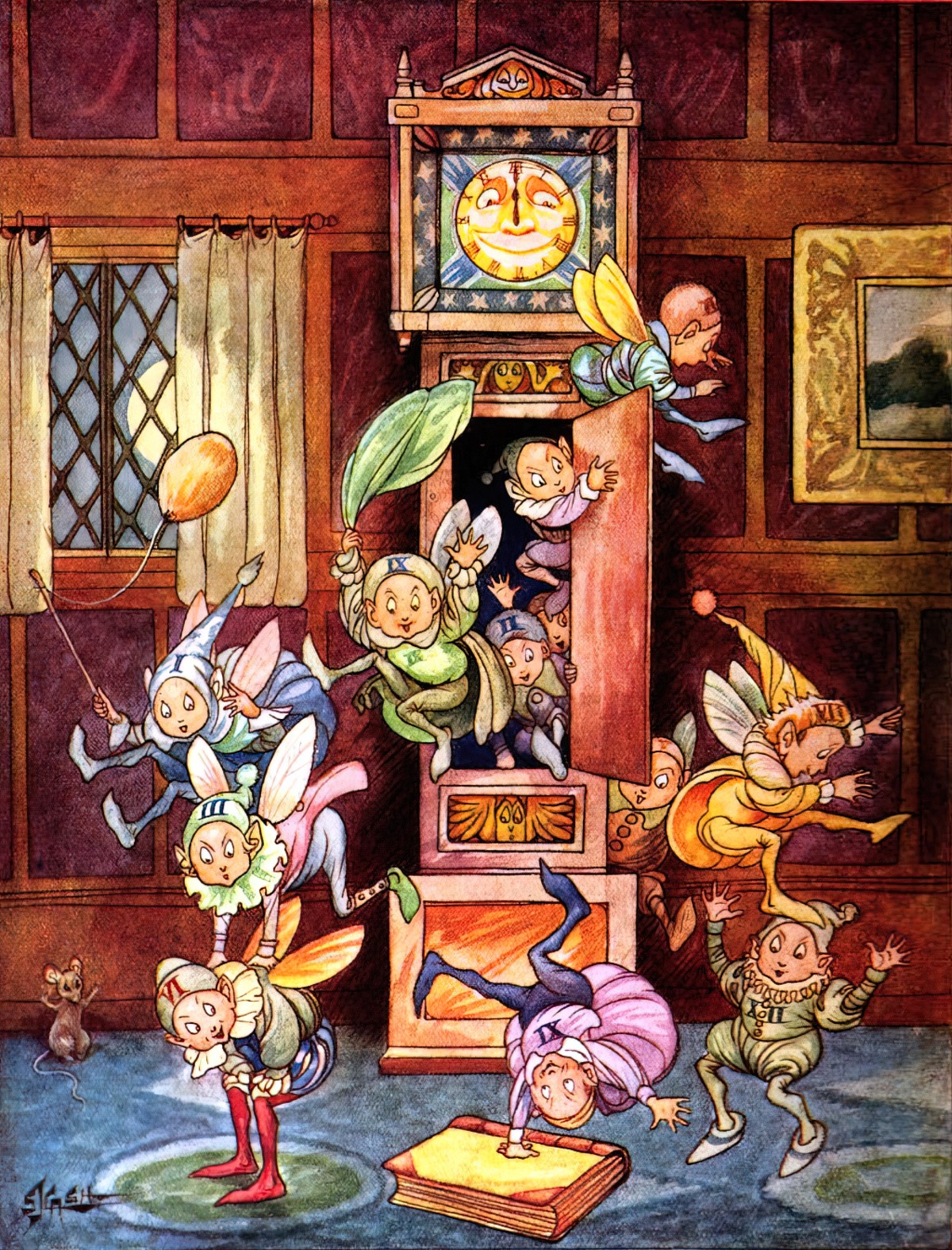

In children’s books, toys and pets become animated when the humans are asleep.

It was the clock that spoke next, startling them with his flat brass voice. “I might remind you of the rules of clockwork,” he said. “No talking before midnight and after dawn, and no crying on the job.”

The Mouse and His Child by Russell Hoban

“He’s not on the job,” said the seal. “We’re on our own time now.”

“Toys that cry on their own time sometimes cry on the job,” said the clock, “and no good ever comes of it. A word to the wise.”

Witching Hour

Witching hour refers to a time of night when witches, devils, demons, ghosts and other supernatural beings are at their most powerful.

WHAT TIME IS WITCHING HOUR?

There is controversy about when witching hour occurs.

Some people say it’s midnight. Others say 3 am. The horror film The Exorcism of Emily Rose utilised this older notion of 3 am. In the world of the story, evil forces mocked the Holy Trinity at 3 am. 3 am also happens to be the inverse of 3 pm. Is is thought that Jesus died at 3 pm. If we fall into the mindset of dualities and inversions, the inverse of 3 pm is clearly not good.

Self-designated witches do in fact consider the number three an important number. (cf. the Threefold Laws and the Triple Goddess.) Nine is also significant precisely because it’s 3 times 3. We might say ‘witching hour’ is midnight and 3 am is ‘devil’s hour. Devil’s hour is at its most potent on the night of Halloween, when the veil between the dead and the living is at its thinnest.

There’s a superstition that waking spontaneously at 3 am in a state of terror means the Devil just paid you a visit, either literally or in your dreams.

Others say witching ‘hour’ is between the hours of 9 pm and 3 am. Most contemporary people would say midnight.)

We know that witching hour is a notion of a magical time when the barrier between the other world and where undead, restless entities may be able to pass over from the other world into the material world. This includes witches and their familiars. Shakespeare used it a fair bit in his plays. Witching hour is generally considered to be between midnight and 3 a.m. in England’s Early Modern period.

One explanation (perhaps post hoc) is that Jesus died at 3 pm, creating a holy aura. And 3 am is the opposite.

I prefer the theory that we are more frightened of that hour of the morning, partly because it’s pitch black, partly because our brains are tired and less able to repress scary thoughts, and also because metabolism is optimised for sleep. This means the brain is also optimised for death. Statistically speaking, it is slightly more likely that we’ll die at this time of the night than at any other time of day. Metabolism is in a slump. There’s a reason why we call overnight work “the graveyard shift”.

For those with a baby in the house, this time of night is also when the baby wakes up for a feed, as it awakened by some outside force.

The 2013 movie The Purge taps into the feeling that beings around us (in this case regular humans) have a deep-seated desire to break free and commit evil. This evil is normally repressed, but only by societal rules.

A wealthy family is held hostage for harboring the target of a murderous syndicate during the Purge, a 12-hour period in which any and all crime is legal.

The Purge synopsis

During the Witch Craze, censure settled upon the so-called witches, thought to be practising non-Christian acts under the cloak of darkness.

Even when supernatural creatures stay quiet, fairytales evince the concept of a magical midnight. Cinderella’s magic will evaporate at ‘the stroke of midnight’.

Likewise, werewolves turn into their wolf form at midnight when where’s a full moon.

MAGIC AT MIDNIGHT BY PHYLLIS ARKLE AND ECCLES WILLIAMS (1967)

Wild Duck glanced down from the inn sign he was painted on, and saw Hare from the nearby Hare and Hounds inn hurrying past. He took Hare’s advice and flapped stiffly down, and so for the first time took part in an adventure that began every midnight and ended every dawn.

SANCTIFIED DEMONS OF THE NIGHT

While some people believe evil happens in the dead of night, others sanctify the fear by re-imagining a benevolent creature instead. Below is an illustration of an angel who arrives to help out with the crops. In Scandinavia, we find folklore about the tomten, who visit on cold, snowy nights and check in on your children and farm animals.

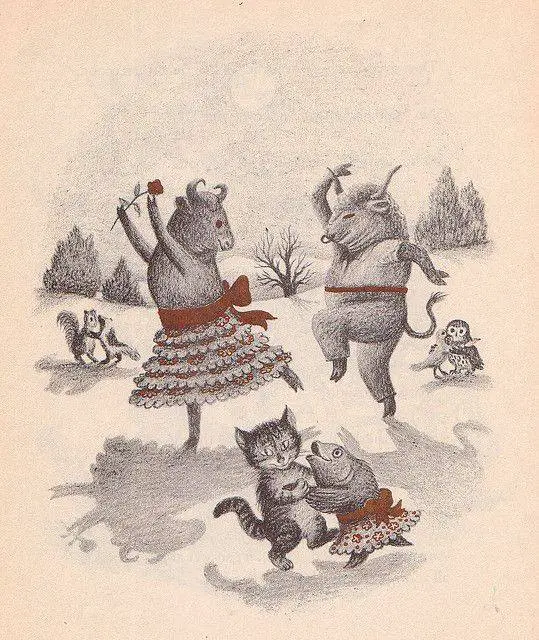

Children’s picture books, especially the carnivalesque kind, also aim to make darkness less scary. The world typically comes alive at night but instead of evil doings, they come out to have fun. There’s laughing and dancing, friendship, frolicking and discovery.

Quite often night-time in children’s stories is as brightly lit as the day. This takes most of the fear away.

Western children have a hard time with that time of the day between being sent to bed (on their own) and falling asleep. There’s A Sea In My Bedroom by Margaret Wild is a good example of that particular fear turned into metaphor. The West has many, many stories for children with the pedagogical function of rendering the lonely night-time less lonely and with less scary monsters.

THIRTEEN O’CLOCK

There’s also a notion that there’s an inbetween hour, which regular humans can’t access. Enid Blyton utilised this in her story Thirteen O’Clock. The story takes place in the middle of the day. Witches arrive on broomsticks after a boy blows thirteen on a dandelion clock.