In children’s fantasy, enchanted realism and magical realism, there is often an arc word (leitwort) which enters popular lexicon, or sticks in the mind long after the reader leaves the story. These magic words sometimes become a part of the child’s own imaginative play, an improvised version of early childhood fan fiction.

Where Do Magic Words Come From?

Imagine a baby on the verge of learning to speak. For all of her life she has been inarticulate — she wants something, but all she can do is cry or say “Uh, uh, uh!” Then, somehow, the purpose of speech is revealed to her, and after what must be a tremendous struggle, the power of speech. Though we all once experienced it, it is hard now to picture the immense thrill of power we must have felt the first time we cried “Mommy!” or “Cookie!” and saw what we desired appear. From this experience, surely, comes the power of magic words and spells in fairytales.

Small children like simple, repetitive rhymes and games, just as they like repetitive or cumulative folktales such as The Gingerbread Man. As they grow older and more competent linguistically they become impatient with such tales; they learn that the magic spell doesn’t always work and that words don’t always mean what they seem to mean.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grownups: The subversive power of children’s literature

Examples of Magic Words and Spells

- Nickety Nacketty Noo Noo Noo by Joy Cowley, in which the spell is in the title

- Harry Potter is full of them: Riddikulus, Obliviat, Alohomora etc.

- The Magic Faraway Tree series by Enid Blyton features trees which whisper ‘wisha wisha’, which as a child reader sent a tingle down my spine. While this onomatopoeia doesn’t directly function as a magic word, it signals that the children have entered an enchanted realm.

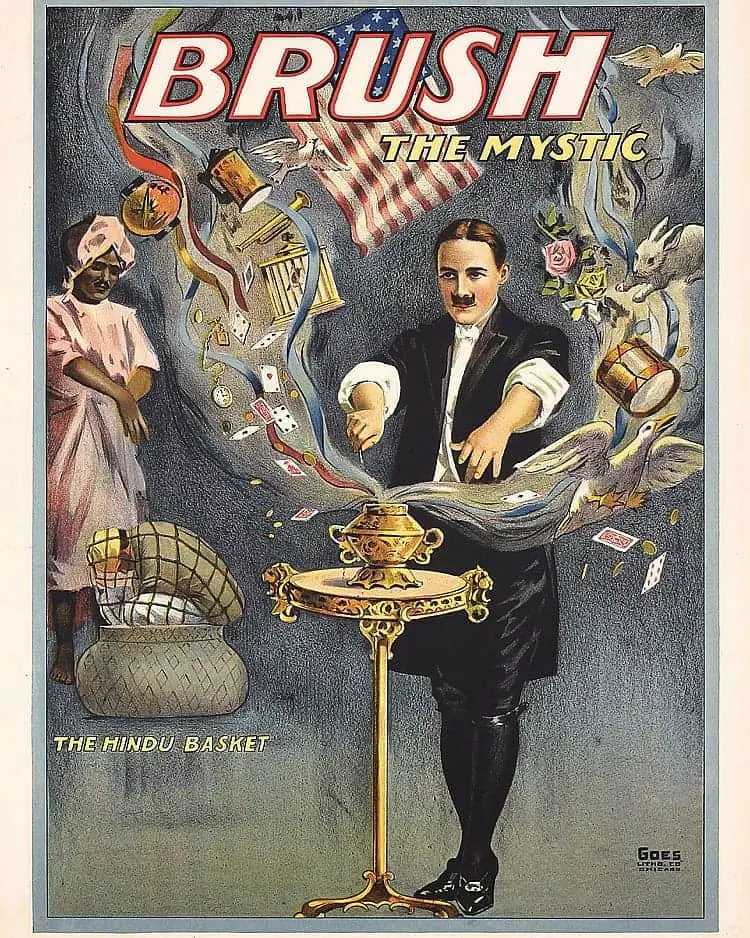

| Abracadabra | In the late 17th century this word was used as a charm to ward off illness. The word comes from Latin and was first recorded in a 2nd-century poem by Q. Serenus Sammonicus. . It comes from the Hebrew phrase abreq ad hâbra, meaning ‘hurl your thunderbolt even unto death’. It was usually inscribed inside an inverted triangle. |

| Presto! | From Italian ‘quick, quickly’, from late Latin praestus ‘ready’. In modern English, it’s usually ‘Hey, presto!” This is because magicians started using ‘Hey presto!’ in the late 18th century. English speakers first borrowed presto from Italian as a musical term. |

| Shazam | This is relatively new, dating only from the 1940s, and a guy called Gomer Pyle, who popularised the Marvel Comics word. |

| Ta-da! | This is from the art deco era, and is simply mimetic, meaning it’s the sound we imagine is made when a magician makes a flourish and presents something magical to the audience. |

| Voila! | French (voilà) from the 1700s, basically means ‘Look!’ |

EXAMPLES OF MAGICAL WORDS AND SPELLS FROM FICTION

- “Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble” [Macbeth]

- “Hubble, bubble, toil and trouble” [Roald Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes]

- “Hubble bubble, toil and trouble, make this task a little double” [The Witches]

- “Hubble, bubble, cauldron bubble” [The Three Witches]

- “By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes” [Macbeth]

- “Double, double, toil and trouble” [Macbeth]

- “Eye of newt and toe of frog” [Macbeth]

- “Mathematici, aperite portas” [The Faerie Queene, written by Edmund Spenser in 1596]

- “Sesame, open!” [Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, from One Thousand and One Nights, also known as Arabian Nights, compiled in the 9th century]

- “Hic haec hoc” [The Mysterious Stranger, written by Mark Twain in 1908]

- “Misticus, latinus, marinus” [The Necromancers, written by Robert Hugh Benson in 1909]

- “Xiccarph” [The King in Yellow, written by Robert W. Chambers in 1895]

- “Agla” [The Key of Solomon, written in the 14th or 15th century]

- “Alohomora” [The Magus, written by Francis Barrett in 1801]

- “Abracadabra/ABC/Mermaid lass of the glass hill sea,/A-flip your tail/And a-flop to me/Twenty and twenty is ten/you see.” [The Witch Family by Eleanor Estes]

- “Higitus Figitus” [The Sword in the Stone]

- “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” [Cinderella]

- “Alakazam!” [Bewitched]

- “Sim Sala Bim” [Bewitched]

- “Higgledy-piggledy” [The Worst Witch]

- “Wingardium Leviosa” [The Worst Witch]

- “Expecto Patronum” [The Worst Witch]

- “Flickum bicus” [Bedknobs and Broomsticks]

- “Treguna Mekoides Trecorum Satis Dee” [Bedknobs and Broomsticks]

- “Hocus pocus” [The Anatomy of Legerdemain: The Art of Jugling, written by H. Dean in 1722]

- “Hocus Pocus” [The Berenstain Bears and the Spooky Old Tree]

- “Aloha mura” [Hocus Pocus]

- “Abracadabra” [The Magic School Bus: Rides Again]

- “Zippity zoppity, give me the hoppity” [Chicka Chicka Boom Boom]

- “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe” [The Secret Series]

- “Kalamazoo, Alakazam, Alakazoop!” [The Littles]

- “Shazam!” [The Marvel Family]

- “Magic words two and two, take us where we want to go!” [The Magic Tree House]

- “Shazam” [Shazam!]

- “Presto chango” [Unknown]

- “A la Peanut Butter Sandwiches” [Adventure Time]

- Bippity Boppity Boo [Cinderella]

- Klaatu barada nikto [The Day the Earth Stood Still]

- Scrumdidlyumptious [Charlie and the Chocolate Factory]

- “Conjunctivitis!” [Matilda]

- “Transformo!” [Matilda]

- “Iocane Powder” [The Princess Bride]

- “Zim zala bim” [Sabrina, the Teenage Witch]

- “Hex, little frog, do your duty” [Halloweentown]

- “Asesino de reyes” [The Kingkiller Chronicle by Patrick Rothfuss]

- “Shazam” [The Sandman by Neil Gaiman]

- “Klytus, I’m bored. What plaything can you offer me today?” [Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond]

- “Gestae, scelerum, et mea fata” [The Witcher by Andrzej Sapkowski]

- “Fus Ro Dah” [The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim video game]

- “Aiaiaiaiaiai” [The Aeneid by Virgil]

- “Sancta Camisa” [The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett]

- “Semper Fidelis Tyrannosaurus” [The Dresden Files by Jim Butcher]

- “In praeceptis meis dirige me” [The Black Company by Glen Cook]

- “Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul, ash nazg thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul” [The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien]

- “Ex oblivione, ex abysso, ex machina” [The Library at Mount Char by Scott Hawkins]

- “Eisenguard” [The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan]

- “Klaatu barada nikto” [Army of Darkness]

- “Zim zam shabam” [The Fairly OddParents]

- “Mezmerelda’s incantation” [The Little Mermaid TV series]

- “Alakazam” [The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends]

- “Bewitch us, twitch us, make us a sandwich” [Looney Tunes]

- “Cackle cackle, Madame Medusa” [The Rescuers]

- “Mimsy, borogoves, and slithy toves” [Tiny Toon Adventures]

- “By the power of Greyskull” [Masters of the Universe, directed by Gary Goddard]

The name, and the words ‘hocus pocus,’ which were often chanted during tricks involving sleight of hand, is a corruption of the Latin blessing from the Catholic mass, Hoc est corpus meum, meaning“This is my body.”

What makes a good magic word?

For the answer to this, I turn to the work of scholars who have studied nursery rhymes. Nursery rhymes have a proven track record for memorability and infiltration into the real lives of children (and caregivers).

In her paper “From nursery rhymes to childlore: orality and ideology“, Catalina Millán Scheiding writes about the enduring popularity of nursery rhymes under the following headings:

- Rhythm — rhythm is an especially important aspect of the prosody of nursery rhyme (along with intonation, stress and tempo of speech). Then there’s isochrony (e.g. whether a language is stress-timed or syllable timed). Children’s rhymes tend to have a ‘binary structure’ e.g. quatrains, or four-beat lines (Baa Baa Black Sheep). Some have proposed that this is because they mimic heartbeats, which we remember from our time in the womb. Nursery rhymes often offer a sense of closure in their rhythm. This is known as a ‘closed circular structure’. Scheiding offers Baa Baa Black Sheep as an example of this. John Prine’s Prine’s rhythmic delivery of “Illegal Smile” is likewise phrased ‘like a children’s sing-along, emphasizing the final two syllables of each line: “I chased a rainbow down a one-way street — dead end/And all my friends turned out to be insurance — sales men.”’

- Musicality — refers to metrical pattern and how rhythm is marked. English is an example of a ‘stress timed language’, which means native English speakers in most dialects around the world leave the same length of time between stressed syllables. (Māori background speakers in New Zealand often speak native English without the stress timing, borrowing Māori syllable timing unrelated of whether they also speak Te Reo Māori.) ‘Musicality’ of an utterance will partly depend on who is uttering it.

- Repetition — Binary structures lend themselves to repetition. Rhyme is another form of repetition and the following observation is especially interesting:

Rhymes are generally rooted in the sensory world and make reference to people, objects, and actions, but not ideas, although ideas can and are inferred and assumed from the short actions found in the rhymes. This situational nature makes rhymes more recognizable, as the objects and actions they depict are related to the culture they belong to, and can be found in daily actions. A rhyme could then be recalled and ‘activated’ when in contact with any of these domestic activities which it mentions.

Debbie Pullinger, From Tongue to Text: A New Reading of Children’s Poetry

- Formulaicity — babies initially learn language as ‘units’ and later as linked strings of words, initially unaware of divisions. Much adult language is also formulaic, and these shared phrases are an important part of a community’s identity.

- Language as Play — Memorable phrases are phrases which form the basis of play. Audiences incorporate them into play and build on them, using the original as a model. Where magic words and rhymes accompany movement (e.g. clapping, skipping, jumping) they become more memorable. Memorable phrases are performative (contrasting with descriptive).

Magic Words Revisited

- Nickety nacketty noo noo noo appeals because of its repetition, its musicality and its rhythm.

- Wisha wisha is beautifully onomatopoeic, and whenever I hear wind blowing through trees, I think they are saying ‘wisha wisha’. This is in line with Pullinger’s theory that the best nursery rhymes (and also the best magic words) are situational, found in daily actions (or natural phenomena).

Header painting: The Magic Circle 1886 by John William Waterhouse 1849-1917