A Long Way From Chicago by Richard Peck is a Newbery Honor book from 1998, set in the era of The Great Depression. An adult narrator looks back and remembers his wily trickster grandmother. This book is one of the most moving and well-written children’s books I’ve read, at once comical and resonant.

This is the first of a trilogy. The second is A Year Down Yonder. The third is A Season Of Gifts.

Mary Alice remembers childhood summers packed with drama. At fifteen, she faces a whole long year with Grandma Dowdel, well known for shaking up her neighbors-and everyone else. All Mary Alice can know for certain is this: when trying to predict how life with Grandma might turn out . . . better not.

The eccentric, larger-than-life Grandma Dowdel is back in this heart-warming tale. Set 20 years after the events of A Year Down Yonder , it is now 1958 and a new family has moved in next door: a Methodist minister and his wife and kids. Soon Grandma Dowdel will work her particular brand of charm on all of them: ten-year-old Bob Barnhart, who is shy on courage in a town full of bullies; his two fascinating sisters; and even his parents, who are amazed to discover that the last house in town might also be the most vital.

As Christmas rolls around, the Barnhart family realizes that they’ve found a true home, and a neighbor who gives gifts that will last a lifetime.

THE COVER OF A LONG WAY FROM CHICAGO

On all the various covers of A Long Way From Chicago the image of Joey in the plane features strongly. In one of the chapters Grandma finagles Joey a ride on a plane at the country fair but the plane ride itself is very much secondary to the chapter, in which we and the child characters learn the extent of Grandma’s cunning — as well as how tricks can somehow backfire.

So what’s with the centrality of the plane illustration?

Rumours are things with wings, too.

A Long Way From Chicago, p 118

Later in the story, a few years after Joey has ridden in that plane at the circus, Grandma shows him the power of rumour and gossip. It can be used for good, or it can be used for evil. Most often, it’s somewhere in the middle.

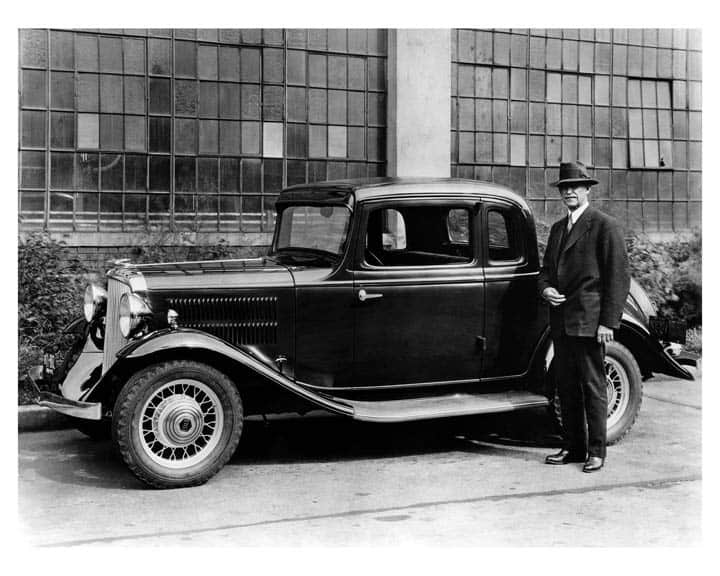

The car Joey loves to drive, not coincidentally, is called a ‘terraplane’ (a vehicle that ‘flies’ across terrain). The terraplane was a type of automobile produced by the Hudson Motor Company, previously called Essex. This particular type of car was designed to be more affordable, for families.

The Terraplane and I were becoming as one.

Historically literate readers will be keenly aware that Joey will come of age just as WW2 breaks out. I read this story without really acknowledging that fact, but in the final chapter we realise it is so, and of course he wants to fly planes. The experiences of his childhood summers with Grandma have lead to his wish to be a fighter pilot.

For more see The Symbolism Of Flight In Children’s Literature.

NARRATION AND TRUTH

The boy narrator is Joey Dowdel, a first person storyteller. His sister is Mary Alice Dowdel, two years younger.

Because there is a full year elapsing between each story, the children change a lot. While each summer with Grandma teaches Joe something elemental about life, a lot of the change happens off the page, in the way that kids of that age change a lot year by year, regardless of what they’re doing.

The ageing of the children is the thread propelling the story forward in a linear direction. This line gives shape to the separate incidents taking place each summer. Without this narrative thrust the incidents would suffer the same problem as any journey story — the various characters and incidents would seem disconnected and the story as a whole would seem scattered.

Is this a coming-of-age story, then? Yes, but only insofar as any story about kids this age is a coming-of-age story. But this story isn’t about Joey and it’s not much about Mary Alice, either. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a bystander narrator entering a community and the star of this story is the grandmother he spends summers with. Eventually, the grandchildren learn all the tricks of their grandmother, picking people’s shortcomings to do what they feel is good in the community.

Truth is a popular topic when it comes to middle grade literature, and the same applies here. When you were little you were told to never lie. But now you’re in middle childhood you’re starting to realise that good people lie for good reasons. Look and learn. That’s what’s happening in this book.

The choice of narration is an excellent vehicle for this kind of theme:

“Are all my memories true? Every word, and growing truer with the years.”

This is a twisted spin on unreliable narration — Joey is old enough now to have a deeper understanding of the things he experienced as a child. Whereas we might expect old Joe’s memory for exact details to have faded somewhat, we are to trust his general interpretation of events, and the wisdom he brings to this long-ago story.

“We knew kids lie all the time, but Grandma was no kid, and she could tell some whoppers. Of course the reporter had been lied to big time up at the cafe, but Grandma’s lies were more interesting, even historical. […] What little we knew about grown-ups didn’t seem to cover Grandma.”

“[The ghost — actually cat — in the coffin] was a story that grew in the telling in one of those little towns where there’s always time to ponder all the different kinds of truth.”

SETTING OF A LONG WAY FROM CHICAGO

When these scenes take place it is always August — the hottest time of the year.

That first summer it is 1929.

THE WIDER WORLD

This is the America of:

- Al Capone, Bugs Moran

- The St Valentine’s Massacre

- Prohibition — alcohol is banned, which achieves little but serve to make bootleggers rich.

- Joey and Mary Alice’s family in Chicago has no car telling us they don’t need one due to living in a city but also that they’re from an ordinary middle class family. By 1931 the Great Depression hasn’t yet ‘bottomed out’ but is heading that way.

THE COUNTRY/CITY DIVIDE

In Chicago there are characters such as the real life John Dillinger, who robbed banks with two female accomplices. Richard Peck makes reference to these in part to contrast Chicago with this small town.

Once in the country, Joey is the ingenue narrator, describing the town as an outsider. (This is a useful trick because readers are also outsiders.) Joey tells us that back then, Chicago has an ‘evil’ reputation.

- Prairie chickens can still be seen waddling about

- Horses are still common in the rural towns, though the rich family in town drives a Hupmobile.

- Fireworks — baby-wakers, torpedoes, bigger one is called a Cherry bomb

- Snowball bushes grow in Grandma’s yard, which later come in handy for breaking a fall. I doubt they’re all that soft to land on, but they certainly have that image.

- Grandmother lives in a small town ‘the railway tracks cut in two’. We know how sleepy and unexciting it is because we are told that people stand out under their verandahs to see the train pass by. This town is somewhere between Chicago and St. Louis.

- “The Coffee Pot was where people went to loaf, talk tall, and swap gossip.” Story arenas need some local meeting place for the community. Gilmore girls also has a coffee house, as does Twin Peaks, Friends, 13 Reasons Why and many other stories about a community of people. Especially cosy stories.

- There is a local Holy Rollers church — ragtime and tambourines in the church at night. A Holy Rollers church refers colloquially to Christian churches of the Pentecostal or Holiness type — the kind where there is a lot of singing, standing up, moving about and falling down. It can be used derisively but has also been reclaimed by members of these churches themselves. There’s also the more staid United Brethen Church, where they have the rummage sale.

CHARACTERS IN THIS STORYWORLD

Fictional small towns where nothing much usually happens almost always have a town gossip. Effie Wilcox is the town gossip in A Long Way From Chicago, “whose tongue is attached at the middle and flaps at both ends.” Cosy mysteries need town gossips because the (usually old ladies) who solve the mysteries don’t have easy ins at the local police station (though they’re often related somehow to a copper.) Likewise, kids benefit hugely from a town gossip — being kids, their main insight into the adult world comes from hearing adults talk. A variety of mysteries happen in each of these chapters and I initially expected Effie Wilcox to feature more prominently, but as it happens, Grandma herself somehow has her own ear to the ground.

Wolf Hollow also has a town gossip, as does Anne of Green Gables, in Rachel Lynde.

Also like Anne of Green Gables, A Long Way From Chicago features a mouse in the food (milk, though planted). This must have been a reasonably common occurrence in rural areas before fridges and modern housing. The grandmother is a trickster archetype — a common character archetype beloved by audiences. She’s getting up to tricks like a character out of a Roald Dahl novel, putting the mouse in the milk. I’m reminded of The Twits.

FOOD

They eat things like green beans and fatback for dinner followed by layer cake. For breakfast: pancakes and corn syrup, fried ham and potatoes and onions. See also: The Evolution Of Fictional Breakfasts.

Nehi is a type of orange pop sold for a nickel a bottle. There are also grapettes, Dr Peppers.

Lack of refrigeration affects what they can eat. Food is home cooked and homegrown, especially at Grandma’s house, as she abhors spending money.

ENTERTAINMENT

- Mary Alice is reading The Hidden Staircase by Carolyn Keene (a Nancy Drew mystery novel). The Nancy Drew stories are themselves mysteries, and Mary Alice’s interest in helping people out may have influenced her decision to harbour a runaway.

- Tom Mix movies — an American actor well-known for his cowboy movies. Westerns were popular at this time — it wasn’t until after the world wars that Westerns turned into anti-Westerns.

- Skipping ropes, skipping chants about presidents, puzzles of famous people.

- Tap dancing is popular with girls due to Shirley Temple.

DIALECT

Some of it is regional, some owing to the era.

- Working like bird dogs

- You’uns instead of y’all.

- Throwed instead of thrown

- Lit running means ‘started running’

- Chilrun

- Pecks of potatoes

- Dagnab it

- Stir yer stumps

- ‘Specialty house’ equals a privy equals an outside toilet

- Skin to the church and get their maw and paw.

- One of the characters is called ‘Miz’, which at first looks like an unnecessary call to attention of the woman’s unmarriageability, but it’s no such thing — at that time in that part of America women were called ‘Miz’ So-and-so, and it was simply a respectful generic used traditionally. This applied to the American South and places like St Louis.

Family means what you need it to, here. Though Aunt Puss is no blood relation of Grandma’s, the grandchildren are, yet Grandma does not acknowledge to Aunt Puss that they are her own.

TIME

Peck’s treatment of time in this novel borrows from the Gothic tradition.

There are still people alive in this story who fought in the Civil War. It is clear from The River Between Us that Richard Peck’s reason for writing for children (or at least part of it), is to connect young readers to generations they’ve just missed out on knowing. As an older writer, this is something he can do for us.

In A Long Way From Chicago, Aunt Puss exists as a link to this earlier era. Aunt Puss has dementia and hasn’t noticed the passing of time. She thinks Grandma, Joey and Mary Alice are all the same age.

This does something for the reader’s appreciation of time. A Long Way From Chicago was first published in 1998, so the young reader is about 3 generations younger than Joey, 5 younger than Grandma and 6 younger than Aunt Puss.

But here we all are, each of us a child at some point, each of us connected by this story. Scholars would use the word ‘chronotope’ to describe the treatment of time in literature. Below we have a good explanation of why the Gothic chronotope is particularly well suited to coming-of-age stories like Peck’s:

The Gothic chronotope is often a place, very often a house, haunted by a past that remains present. As a child grows, more and more experiences, good and bad, displace into memory, forming the intricate passages where bits of his or her past get lost, only to re-emerge at unexpected times. The child’s mind becomes a crowded, sometimes frustratingly inaccessible place at the same time as his or her body morphs in uncomfortable ways. […] Gothic motifs of the uncanny are particularly apt for the metaphorical exploration of the vicissitudes of adolescent identity. The uncanny emerges in the adolescent novels they explore to both highlight change and trigger it. It becomes a complex metaphor for the transition the characters undergo with respect to their place in their families and their family history. […] the Gothic also offers fertile ground to explore beyond the conventions of the family to the adolescent’s place in larger social and cultural constellations of identity The results can affirm psychological models of development of they can open those models of development up to scrutiny and critique.

The Gothic In Children’s Literature: Haunting The Borders

The expedition into the past is further extended in the Centennial Summer chapter, when the town lives in the past for a week and dresses in old-fashioned clothes. This is when Joey meets the very old man who apparently fought in the Mexican War. Joey can hardly believe it — the Mexican War was so long ago. Joey himself will be fighting in a war when he gets older. These experiences, where he meets people who have lived through similar events before him, will contribute to his understanding of why he is fighting.

STORY STRUCTURE OF A LONG WAY FROM CHICAGO

This novel could be considered a series of interconnected short stories. I wasn’t surprised to read that the first chapter began as a short story, but Richard Peck realised he could get a lot more mileage out of Grandma Dowdel, so continued writing. Because each chapter is a short story in its own right, it’s possible to break down the structure of each one separately — each has its own desire/plan/big struggle/self revelation sequence. Instead I’ll make some general observations.

SHORTCOMING

Grandma Dowdel comes across — at first — as a misanthropist. She keeps to herself, doesn’t seem to have any friends in town and is so good at lying and tricking that she seems to be on the sociopathic spectrum. Her mistrust of people seems her main shortcoming, shown in the first chapter by the Cowgill boys picking on her as a target, first shooting her letterbox, next hoping to steal her gun.

DESIRE

Grandma Dowdel is gradually revealed to be not a misanthropist but a kind-hearted person who fights for the little guy. She is probably something like INTJ on the Myers-Briggs.

Grandma wants to make the world a better place. At least, her little town. She does not want glory for doing so — she wants to be left alone to do her good deeds. These deeds in themselves give her purpose. Her reasons for doing these things come from within. Unlike the vast majority of rural Americans at that time, Grandma Dowdel is wholly unconnected to the local (Holy Roller) church.

Although Grandma is the main character of interest in this story, Joey himself undergoes the classic ‘doubling down of desire’ that you often see in stories when the main character is required to do something against their will. Joey does not want to spend summers with his grandmother in hillbilly county.

Is Illinois really hillbilly country?

‘Hillbilly’ towns are found in Appalachia (Upstate New York, Western Pennsylvania, East Central and Southeastern Ohio, Western Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama).

However, another hillbilly region could be considered people residing in the Shawnee Forest region of Southern Illinois, or the Illinois Ozarks as they are called, and also South Central Missouri. This area starts around Rolla then heads southwest to Springfield and south into the Northern 2/3 of Arkansas.

The Ozarks and Appalachia are what make up the primary region of “hillbilly” country. Note that hillbillies are therefore not exclusive to the South, as they reside in a good chunk of Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Upstate New York.

But sure enough, when we get to almost the middle of the book, both he and his sister have changed their mind. They now both actively want in on these adventures with Grandma:

I don’t think Grandma’s a very good influence on us,” Mary Alice said. It had taken her a while to come to that conclusion, and I had to agree. It reconciled us some to our trips to visit her. Mary Alice was ten now. I believe this was the first year she didn’t bring her jump rope with her. And she no longer pitched a fit because she couldn’t take her best friends, Beverly and Audrey, to meet Grandma. “They wouldn’t understand,” Mary Alice said.

We weren’t so sure Mother and Dad would either. Since we still dragged our heels about going, they didn’t noticed we looked forward to the trip.

A Long Way From Chicago, Page 61 (out of 148 pages total)

This change in desire is marked with the odd snippet of dialogue in which Joey accidentally comes out with regional dialect.

In each chapter Richard Peck sets up the desire without telling us that’s what he’s doing. For instance, in The Phantom Brakeman the story opens with Joe and Mary Alice at The Coffee Pot enjoying a Nehi soda. We’re told these drinks cost exactly a nickel. We’re also told how hot it is, and that there’s no air-conditioning, and just plunging one arm into a barrel of water provides relief. Later, when Joe is asked to do something for a nickel, it’s very clear to us just how much Joe wants that drink. We didn’t know that the heat of summer and the price of the drink were going to be significant — at the time it seems like Peck is simply setting the scene.

OPPONENT

Everyone in town is against Grandma Dowdel.

There is the town gossip, the Cowgill boys in the second chapter, the policemen who want to keep drifters out of town, whereas Grandma wants to provide them with a good feed. Then there’s the comical opponent Rupert Pennypacker, who has made an excellent gooseberry pie.

“The Day Of Judgement” chapter also has Joey wanting something badly for the first time — to go for a ride in the plane at the Country Fair. He really wants his grandmother to win the pie competition because then he’ll have the opportunity.

PLAN

Each chapter is a new summer and a new vignette in which Grandma comes up against someone and wins the big struggle by hard work and wits.

Grandma is described as ‘a little grey shape, mouselike’. Mice are smart tricksters themselves. They may be depicted in children’s books as weak and helpless — most often as child stand-ins — but Richard Peck takes the reality of the mouse here when he compares the grandmother to one. Mice are small but they are very brave, and extremely resourceful. They’ve learnt to thrive around people, living on the edge of civilisation. The mouse is an extended metaphor for the grandmother.

As well as mice, Grandma is also associated with gooseberries. Being a sour fruit, the gooseberry is a motif for Grandma’s general demeanour. When Grandma dresses up for the fair, this is the human equivalent of adding sugar to a gooseberry pie to make it palatable.

This is Hillbilly county and from what I learnt reading Hillbilly Elegy, Grandma works by ‘Hillbilly justice’. She’ll lie, thieve, threaten, trick and practise hard to get what she wants. Since the law has their own selfish agenda, she’ll happily take things into her own hands.

BIG STRUGGLE

While each chapter has its own big struggle, the big struggles do not ascend in any approximation to a dramatic arc. Peck has used a variety of big struggle scenes, including slapstick falling from a window to threats with actual guns, but often it takes a less deadly tone.

ANAGNORISIS

Joey realises that he wants to become a fighter pilot, that his sister is growing into a woman, that things change even though children don’t want them to.

NEW SITUATION

Joey sees his grandmother (perhaps for the last time?) as his army train zooms past her house in the middle of the night. She has lit up her house like a Jack-o-lantern even though she is normally really stingy with lighting.

The full meaning of the title now becomes clear. “A Long Way From Chicago” refers to all the international places Joe will visit via plane during the war.

A young adult novel ends not with happily ever after, but at a new beginning, with the sense of a lot of life left to be lived.

Richard Peck