“Loneliness” is a (very) short story by Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz, translated into English by Celina Wieniewska and published in The New Yorker in 1977. Although the story appeared to English audiences in 1977, long after WW2, Bruno Schulz lived from 1892-1942. This story appeared in one of Bruno Schulz’s two short story collections, published 1937.

The author was killed by the Gestapo at the age of 50 while walking home with a loaf of bread. He had written and published two books. Another was partially written; other works have been lost. Bruno Schulz is considered one of Poland’s best 20th century authors.

Like many very short stories (this is a single page in The New Yorker) the language is dense and feels like a poem. (Especially the final sentence, I would say.)

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATION

Celina Wieniewska has more recently been criticised for trying too hard to make Schulz’s work palatable to English speakers. There are now other translations of his work out there.

There’s something about reading literature in translation; even if you don’t know a single word of the original language, you can still hear it in the translation.

PARATEXT OF “LONELINESS”

The narrator, an age-old pensioner, contemplates his loneliness — his room is described in detail, he extends metaphors that describe himself as a field mouse and a church mouse, he thinks about his inability to leave his room.

Introduction in The New Yorker (November 14, 1977)

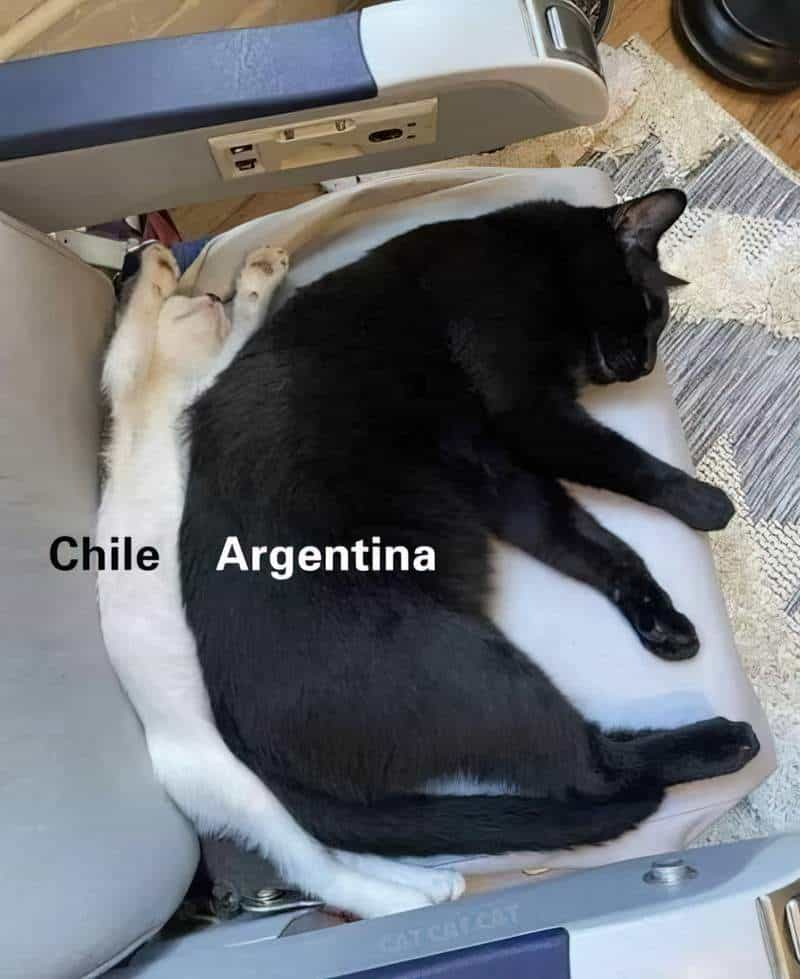

More recently, Chilean poet, short story writer and novelist Alejandro Zambra chose “Loneliness” to read at The New Yorker Fiction podcast and discussed the story with Deborah Treisman. Zambra notes that Schulz is often compared to Kafka, and Schulz even encouraged that comparison by making reference to Kafka in another story from the same collection.

But Zambra is careful to point out the difference. Schulz has a ‘weird sense of humour’. At the same time, his writing is very complex. For all the Kafka analogies, Schulz is unique.

Alejandro Zambra does not think “Loneliness” is Schulz’s ‘best’ story, but it is his ‘favourite’. This is an interesting distinction. Do you have a favourite story which you do not consider to be the author’s ‘best’? It seems to me, sometimes our ‘favourite’ story is the one which contains the most resonant and relatable details.

As you read “Loneliness”, pay attention to the contradictions and juxtapositions. The master contradiction: living and dying (I would say, that space smack bang in the middle). All other juxtapositions support this larger juxtaposition between life and death:

- A bird’s eye view of a room from above, yet the narrative camera zooms in on the flies (which are tiny)

- A white night, yet there’s no moon, so where is the light coming from? (When reading Schulz, be prepared for ‘each sentence to have a mistake’ of the sort a writing teacher may try to correct.)

- An opening which tells us the narrator is dead: ‘immortal and posthumous’. The reader must sit with the discomfort of not knowing whether this guy is a literal ghost, or living a ghostly existence inside the room of his old age (which is also his childhood nursery).

By the way, many stories by Bruno Schulz relate to the father. Here, the father is not present.

SETTING OF “LONELINESS”

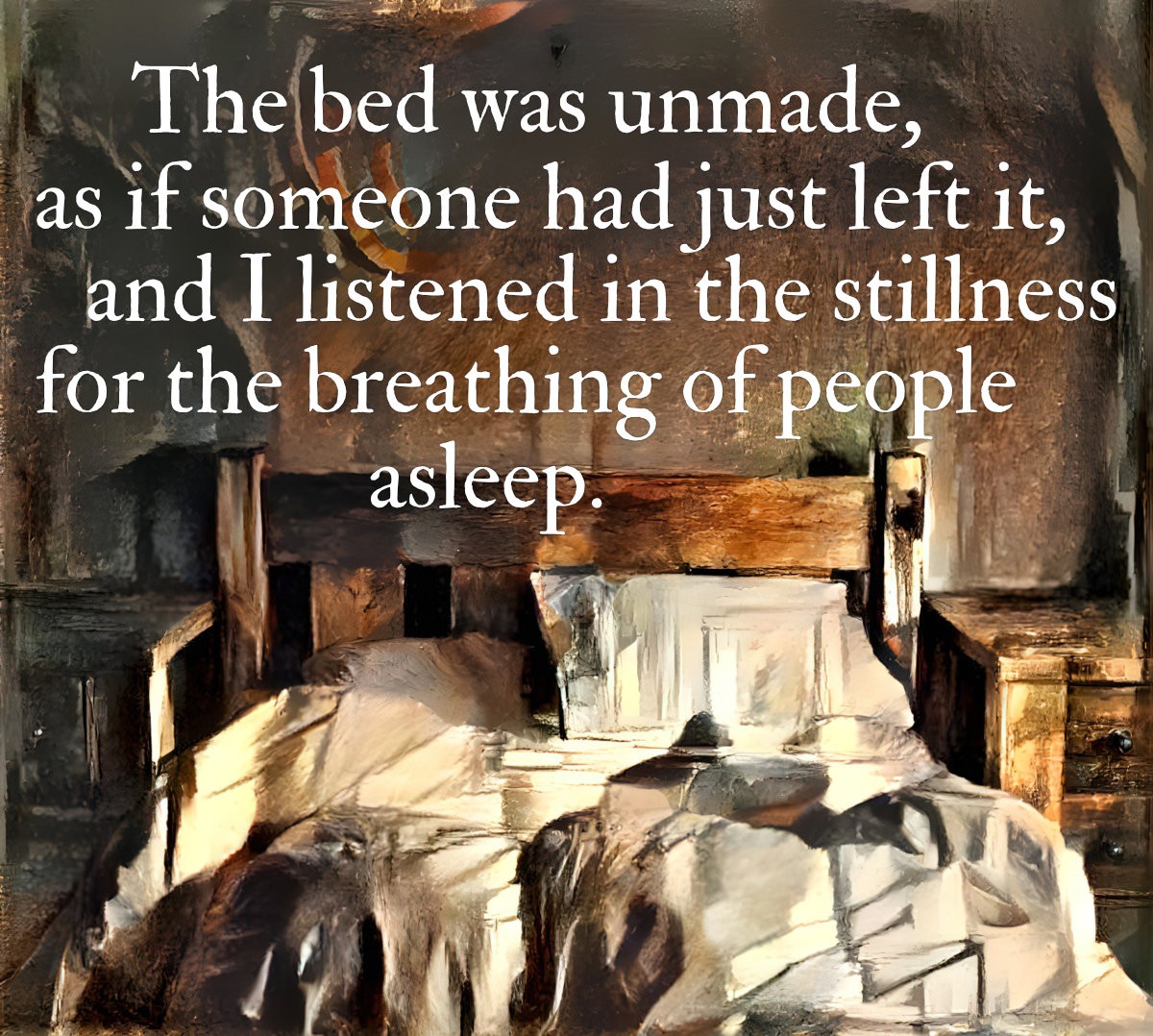

This story is the ultimate timeless story, working with what we might call ‘fairytale time’, kairos rather than chronos. Obviously, the narrative is somewhat modern, as the man is living in the room of a recognisable house, appointed with a mirror, a bed, a curtain rail and therefore a window. But that’s about all we know about the room, which could be anywhere. The narrator arrives in statu nascendi, and could therefore be any of us.

The more details a writer gives, the less universal the story. However, contradicting that, the following is also true: A few well-chosen details are necessary to universalise a story. Well-chosen, resonant details help readers identify with character. A wholly unrecognisable character fails to universalise an experience.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “LONELINESS”

SHORTCOMING

Okay so we don’t know if the old man is dead or alive. I think he’s in that liminal space right before death, a space we can only imagine. But imagine we must, because we’ll all be there one day. (Unless we’re killed instantly, I guess?)

We do know the character is old, but how do we know he is a man (and not another gender)? Extrapolation: Male is the default, but aside from that, we know the author was a man, and there are no overt feminine markers. He thinks of doing somersaults on that curtain rail, suggesting a youth of great upper body strength. (For that, a male puberty is usually necessary.) That said, the tricks taking place on that curtain rail are beyond Simone Biles.

I prefer to think of the narrator as without gender. When this character looks in the mirror he fails to see himself; he has lost sense of self, and surely this would include his own sense of gender.

What we do know: He is not entirely with us, talking to us. For me this narrative is a metaphor for dementia, or perhaps simply for very advanced age, in which other people (and other people’s opinions) simply don’t mean that much anymore because you’re looking death in the eye. At times the narrator seems to be talking to himself, but then he suddenly remembers he is telling a story, and that stories have listeners. “Oh, right, you’re here,” he seems to be saying.

There’s also this: This story is about an attempt to remember what you don’t really remember. “I don’t know, I don’t know, I can’t explain”, on repeat.

DESIRE

Here’s the thing about first person intradiegetic narrators: They tell stories as way of understanding themselves and their situation. There are genre exceptions: Perhaps a criminal first person narrator is trying to exonerate themself. But in general, narrators don’t tell stories to their readers so much as to and for themselves. The numerous grammatical questions sprinkled throughout this short story underscores the questioning raison d’être of this type of narrative.

What would the narrator like to understand? This aspect is absolutely a collaboration between writer and reader (note, by ‘writer’ I don’t mean the narrator). The reader is required to approach a story such as this metaphorically before it means anything at all. I mean, we’re even told to do this, right there on the page, when the narrator directly addresses the reader: ‘This, of course, is to be understood as a metaphor’.

METAPHOR FOR DEATH

For me, this is what the story is about. Specifically, the type of death preceded by years and months of dementia.

METAPHOR FOR BEING A WRITER

Writers (and other artists) may engage with this story on another level.

Schulz breaks the fourth wall by imploring us to read the story metaphorically. Importantly, the author withholds the meaning of the metaphor. “Showing the trick but not showing the trick; still there is a trick.” While writing you are transforming yourself all the time, and also searching. Also while writing, you don’t know where you’re going. Schulz says in the story he’s not in control of his metaphors. They control him. “Ever since my childhood I love to have a bird’s eye view of my room.” The writer looks down as action unfolds, omnisciently able to see everything. Bruno Schulz goes beyond the present and relates to the sacred, to something bigger than us. It’s not joyous, but painful.

Also, it’s often said writing is a lonely existence. Is it, though? Depends what you mean by ‘lonely’. I feel the loneliest people are those who are unable to populate their imaginations with characters, fictional, real, spiritual or otherwise. (I have no idea what I mean by ‘otherwise’.)

In this reading, the final sentence turns the story itself into the character’s door.

METAPHOR FOR A RETURN TO CHILDHOOD

Any story about a very old person is likely to put experienced readers in mind of childhood, as it does for Treisman and Zambra. We tend to think of life as a cycle (or circle) in which elderly people return to the dependency and also the playfulness of childhood. Many, many writers have done just that.

I personally get nothing about childhood from the page, though acknowledge that Zambra clearly does, mostly because of that one detail mentioned above: The narrator likes to imagine a room as if from above. Zambra remembers doing this in his own childhood. (In contrast, I’ve never done that.)

METAPHOR FOR LONELINESS

But shouldn’t we pay attention to the title, in trying to decipher what the story means below the surface? (Plenty of works of art are confusing as heck until we go back to the title.)

Treisman says, “Perhaps being a writer is a lonely thing.” (Linking the writing metaphor to the title.)

Loneliness takes many forms, and however the reader parses this story metaphorically, the metaphor will come back to loneliness. There’s the literal loneliness of being stuck in a room with no company. There’s the loneliness of reflecting on childhood (or any time in history) and understanding you can never go back. There’s the loneliness of being in your own head (as a writer must be) and never being ‘on the same page’ as another human being.

No one in your life is with you constantly. No one is completely on your side.

“I Know Him So Well”, Elaine Paige. (This lyric used to haunt me as a kid in the 80s.)

There’s also the loneliness of preparing for death which, like birth, is a solitary experience, even if you happen to be surrounded by loved ones around your hospital bed or whatever.

OPPONENT

‘Complete narratives require opposition’. This is such a fundamental feature of story that opponents are very easy to pick in almost all narratives. Not only that, we can pick different levels of opponent (the opponents who are on your side, the Minotaur opponent, the opponents who at first appear to be friends…)

But who is the opponent in this story? How to craft opposition when a man is locked inside a room on his own. Not only that, he stays in the room. His mind is as locked-in as his body is; there is no backstory in which he recalls a time when he was arguing with his… whoever.

This is what makes the story function more like a poem. This story is atmospheric rather than a complete narrative. The lack of ‘on the page opposition’ is the reason why.

Even the plainest short story is a poem.

V.S. Pritchett

Could we not argue that the man’s main opponent is himself? Yeah, sure, but that’s always the case in every story. For storytelling purposes, what we’re actually talking about in that case is the character’s ‘ghost’ or ‘fatal flaw’.

PLAN

In my reading, this is a man who has lost a grip on his memories, confined not only to this room but to the present moment. The ‘door’ represents the portal to the other side (death). It is an act of bravery to imagine that door, because in imagining it, he must face death.

Those of us who have never faced life-threatening illness find it hard to imagine ‘making the decision to stay alive’. At least, I have trouble with that. I asked a friend who’d had cancer how that works. Healthy bodies stay alive despite us, but my friend told me, “Yes, when you’re really sick you must make the decision to stay alive.”

I’m reluctant to say too much about this, because ‘willing oneself alive’ has an unfortunate counter-reading in our Western culture in which everyone is responsible for their own health, well-being (and death). To say that someone is ‘choosing to go’ is not in any way the same as saying someone is ‘giving up’ because they’re not ‘brave’ enough or whatever.

For more on that, Barbara Ehrenreich has written extensively on the American attitude towards ‘fighting cancer’ in her book ‘Smile or Die’, which haha, was considered by marketing teams too much for Americans, so Americans get a different title from those of us who bought the book elsewhere. (Americans got Bright-sided. If that’s not the ultimate infantilization, I don’t know what is.)

I read “Loneliness” as an experience of dementia because, before learning more about it (and observing it second hand), I comforted myself with the idea that even if I couldn’t remember what I’d eaten for lunch, I would still have my memories. After all, sometimes people with dementia take great delight in revisiting the past. The past folds onto the present.

However, the scariest thing about dementia is this: The ability to enjoy memories also goes. No assiduous building up a lifetime’s supply of wonderful moments then spending the final years of life living in memory. (“Why didn’t I think in advance about stocking up?”)

No, that’s not how dementia works. Dementia eventually forces people to live in the moment. This narrator is living in the moment, and is pretty good at it, too: “I have always been a lighthearted field mouse, I have lived from day to day without a care for the morrow, trusting in my starveling’s talent.” This contradicts the popular Aesopian wisdom extolled in fables such as “The Ants and the Grasshopper”.

He’s even able to expand it with a type of psychosis: He is becoming part of the larger consciousness again, by morphing into the body of the mouse, paying attention to the sounds made by tiny life forms (though cannot actually hear the sound of any wood worm), noticing the death of the flies and the ephemeral nature of all life. Even in recalling his aunt in the long grey dress, he becomes her. If this guy is really old, surely the aunt is already dead. Hence the greyness of her dress. He is preparing himself mentally to join her in death.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

If we read this story as the struggle of a man in the face of death, then the struggle has been finding sufficient bravery to face death’s door. The opening sentence suggests he has already found this bravery. Then he tells us how it was done, perhaps in order that we may be helped.

The author’s biography provides interesting counterpoint here, because Schulz never made it to old age. He lived under the spectre of death as a Jewish man during the Holocaust and he was probably killed in exactly the way he feared he would be: By Nazis, while performing a mundane, workaday task. Buying bread, of all things.

ANAGNORISIS

Short stories sometimes end with this, the epiphanic moment, the self-revelation, whatever we want to call it. So it is here.

Alejandro Zambra jokes that the final sentence would do well on social media and garner many likes. It’s one of those things that sounds like popular self-help advice (though not in a negative way).

NEW SITUATION

There’s no suggestion that anything happens beyond dying. The moment of death must be left off the page because a dead person can’t write a story, right?

RESONANCE

Alejandro Zambra tells us that the isolation of the covid-19 pandemic had him thinking about this story a lot. It is essentially a dark story of confinement. On the surface level, the story is about someone locked in a room.

Anyone who has ever been alone (especially in a room, especially after facing old age) is likely to get something out of this story.

FURTHER READING

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History

The twentieth-century artist Bruno Schulz was born an Austrian, lived as a Pole, and died a Jew. First a citizen of the Habsburg monarchy, he would, without moving, become the subject of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic, the Second Polish Republic, the USSR, and, finally, the Third Reich.

Yet to use his own metaphor, Schulz remained throughout a citizen of the Republic of Dreams. He was a master of twentieth-century imaginative fiction who mapped the anxious perplexities of his time; Isaac Bashevis Singer called him “one of the most remarkable writers who ever lived.” Schulz was also a talented illustrator and graphic artist whose masochistic drawings would catch the eye of a sadistic Nazi officer. Schulz’s art became the currency in which he bought life.

In Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History (Norton, 2023), Benjamin Balint chases the inventive murals Schulz painted on the walls of an SS villa―the last traces of his vanished world―into multiple dimensions of the artist’s life and afterlife. Sixty years after Schulz was murdered, those murals were miraculously rediscovered, only to be secretly smuggled by Israeli agents to Jerusalem. The ensuing international furor summoned broader perplexities, not just about who has the right to curate orphaned artworks and to construe their meanings, but about who can claim to stand guard over the legacy of Jews killed in the Nazi slaughter.

New Books Network