I often ask African friends who have immigrated to America what most struck them when they arrived. Their answer is always a variation on a theme—the loneliness.

David Brooks

There is a loneliness that can be rocked. Arms crossed, knees drawn up, holding, holding on […] Then there is the loneliness that roams. No rocking can hold it down. It is alive.

Toni Morrison

Best cure for loneliness is solitude.

Marianne Moore

Confronted by too much emptiness … the brain invents. Loneliness creates company as thirst creates water. How many sailors have been wrecked in pursuit of islands that were merely a shimmering?

Margaret Atwood

I am lonely, yet not everybody will do. I don’t know why, some people fill the gaps but other people emphasize my loneliness.

Anais Nin

WILD GEESE

You do not have to be good.

Mary Oliver (1935-2019)

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

It is true when you are by yourself and you think about life, it is always sad. All that excitement and so on has a way of suddenly leaving you, and it’s as though, in the silence, somebody called your name, and you heard your name for the first time.

Katherine Mansfield

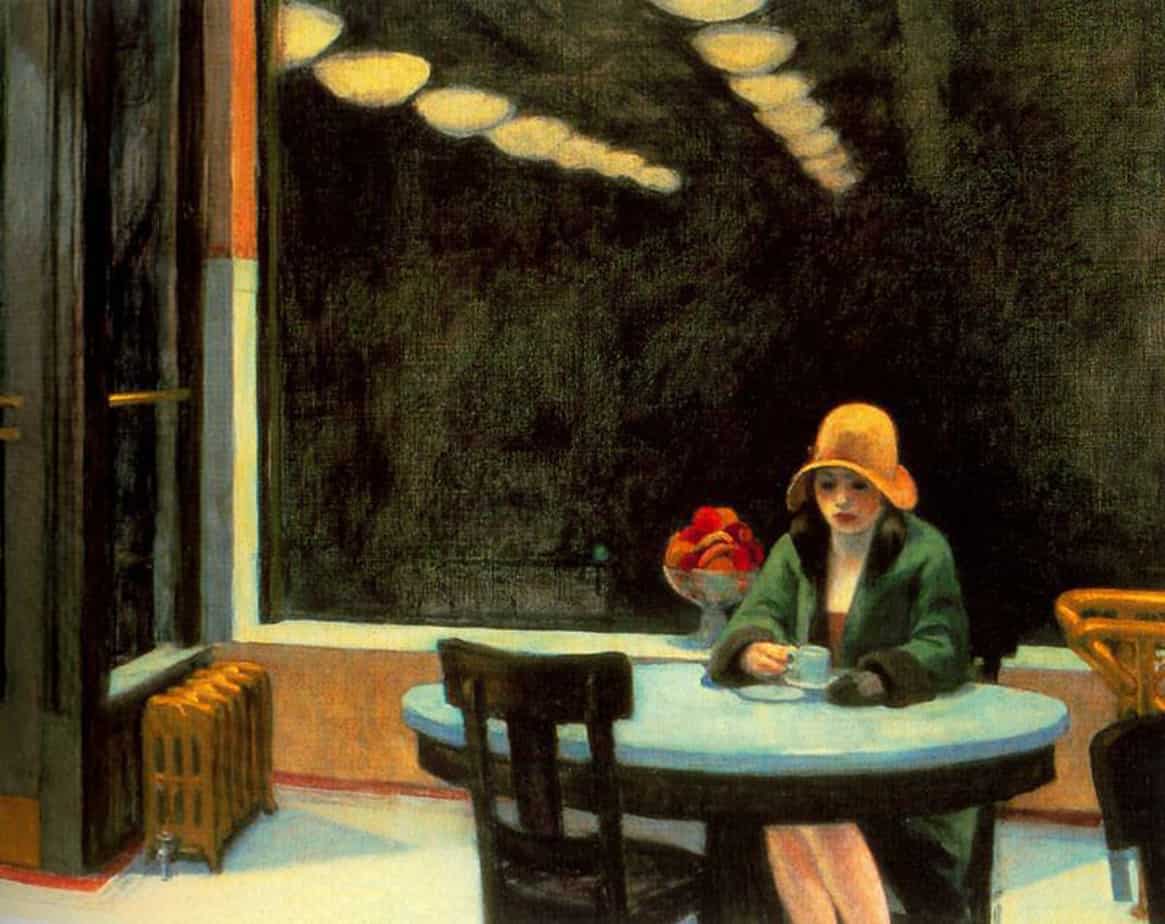

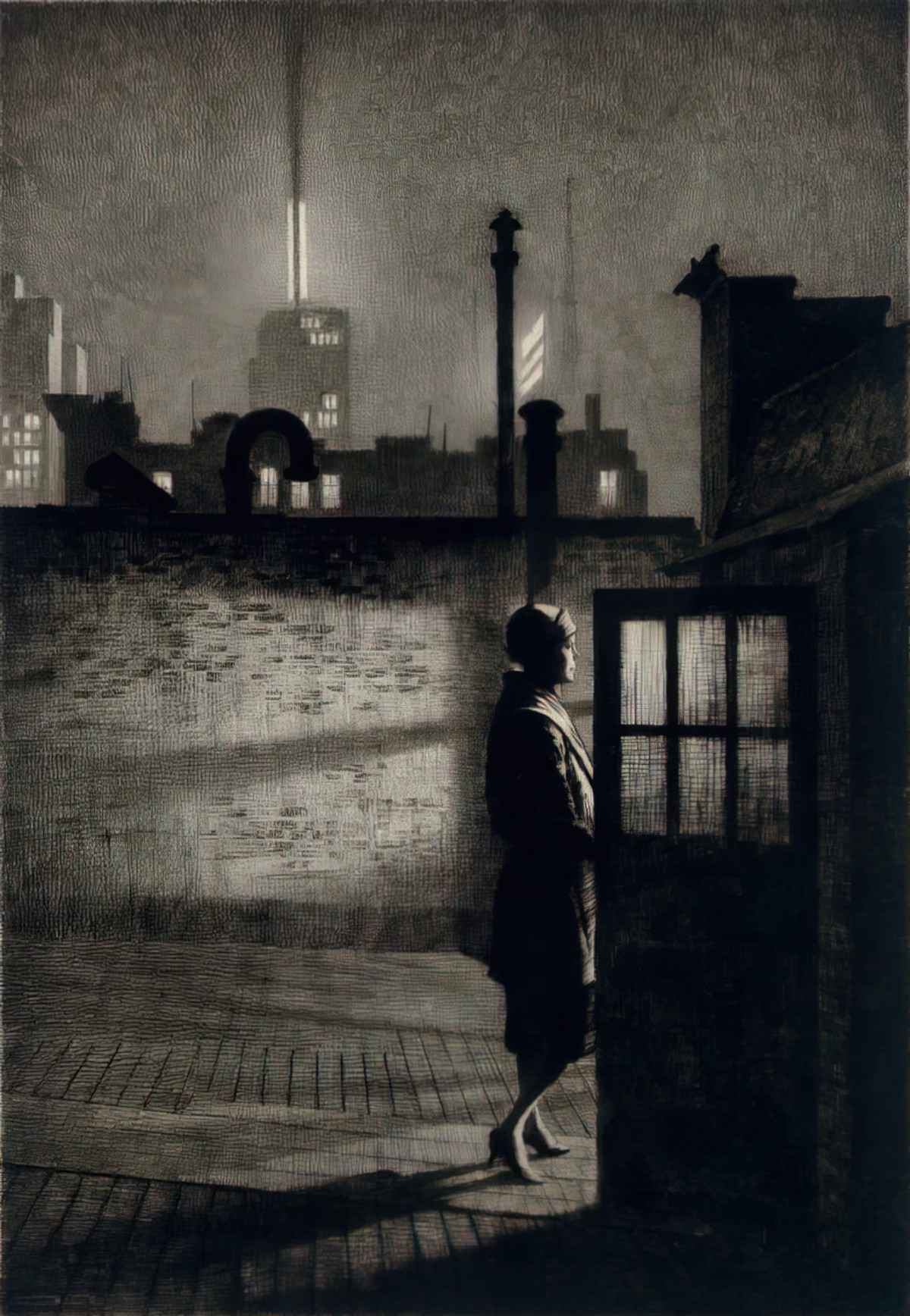

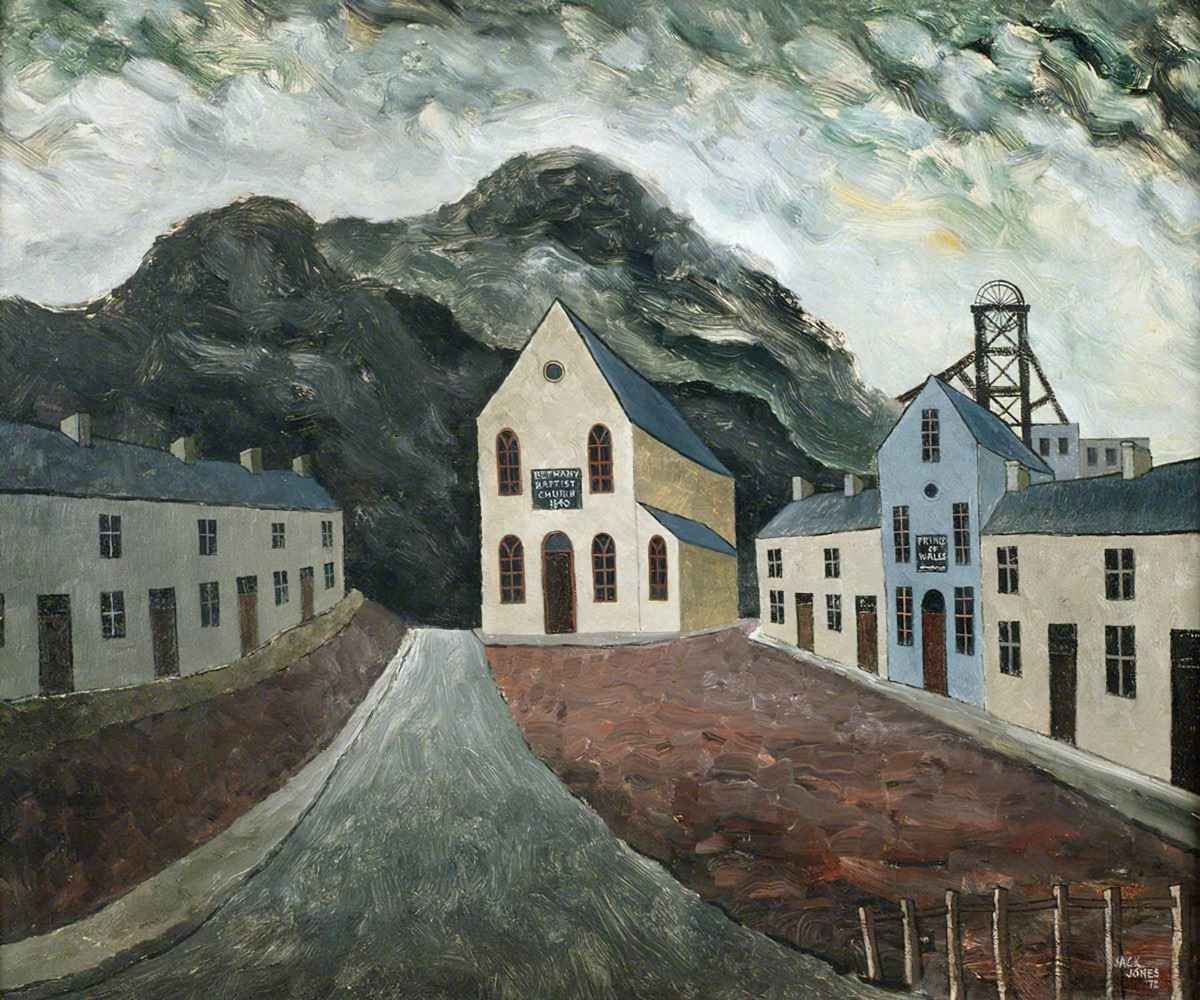

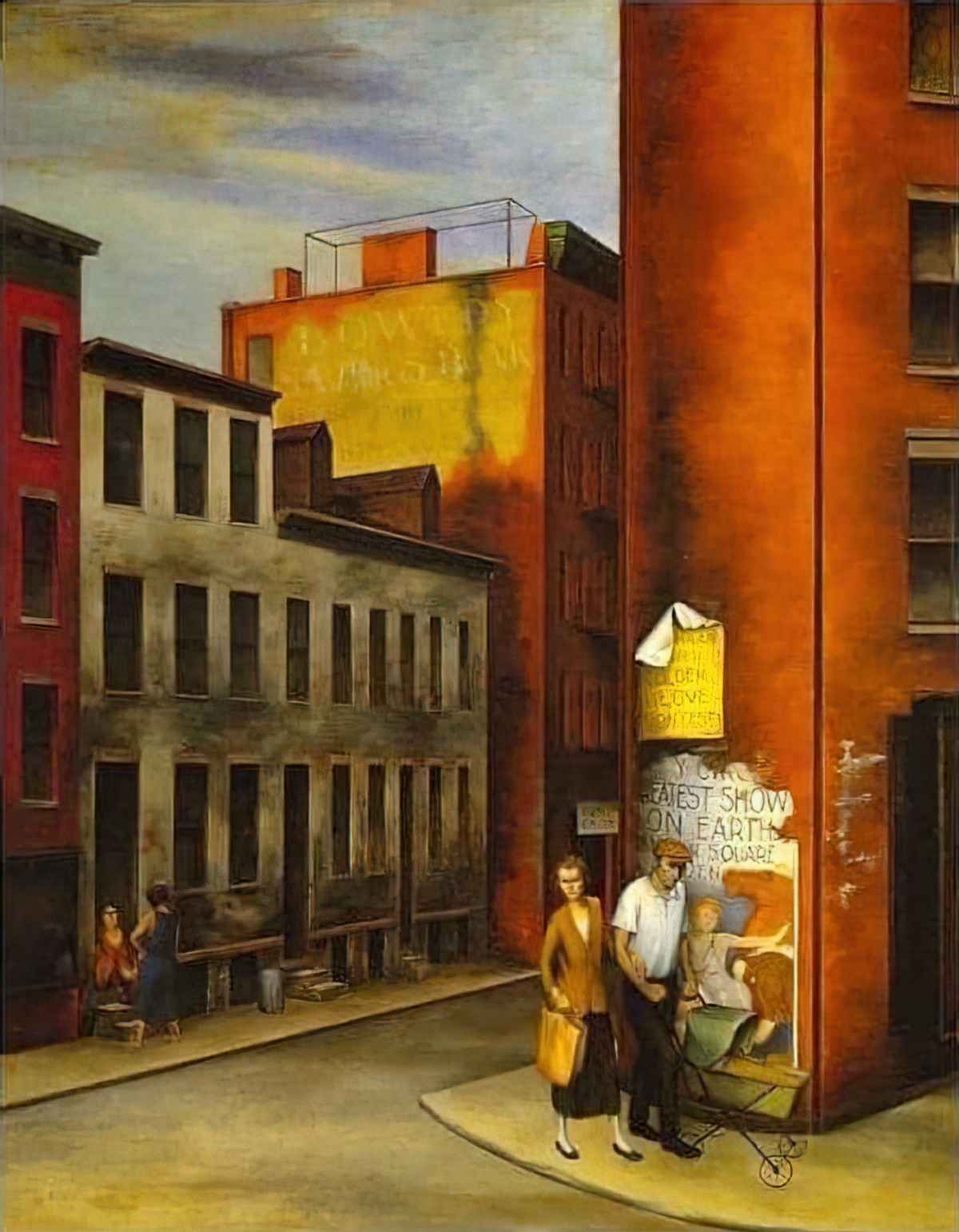

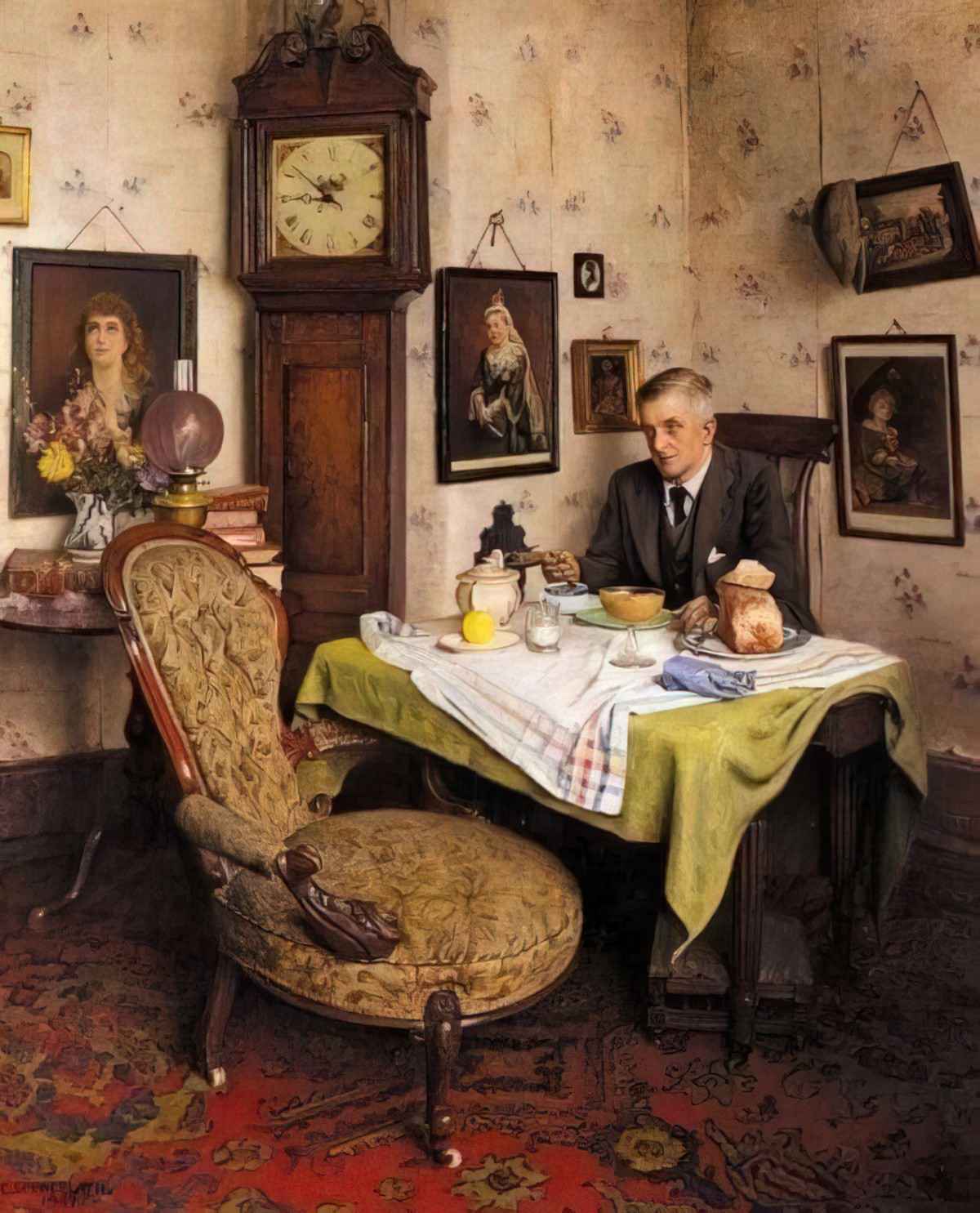

Edward Hopper was a master at depicting loneliness with paint. The sense of isolation is achieved with colour and composition. Eyes don’t meet, or not at the same time. Body language is closed off. Figures are small inside vast spaces, their heads far from the top of the canvas. They gaze from windows as if longing for connection. Edward Hopper did not call this emotion ‘loneliness’, however:

Why did Hopper not want to talk about loneliness? Perhaps he wanted to avoid conflating ‘loneliness’ with ‘isolation’ and in this he was right, as shown by more recent psychological research.

There is only a weak correlation between social isolation (not seeing others) and loneliness, so we don’t necessarily need to fear becoming lonely.

Holly Walker

“Liverpool Art & Illustration – markmyink” has this to say about Hopper’s Automat painting:

Automats were open at all hours of the day and were also ‘busy, noisy and anonymous. They served more than ten thousand customers a day.’ Moreover, the woman is sitting in the least congenial spot in the entire restaurant for introspection.

‘They were clean, efficient, well-lit and – typically furnished with round Carrera marble tables and solid oak chairs like those shown here – genteel.’

By the time Hopper painted his picture, automats had begun to be promoted as safe and proper places for the working woman to dine alone.

Edward Hopper was influenced by a number of artists including Martin Lewis.

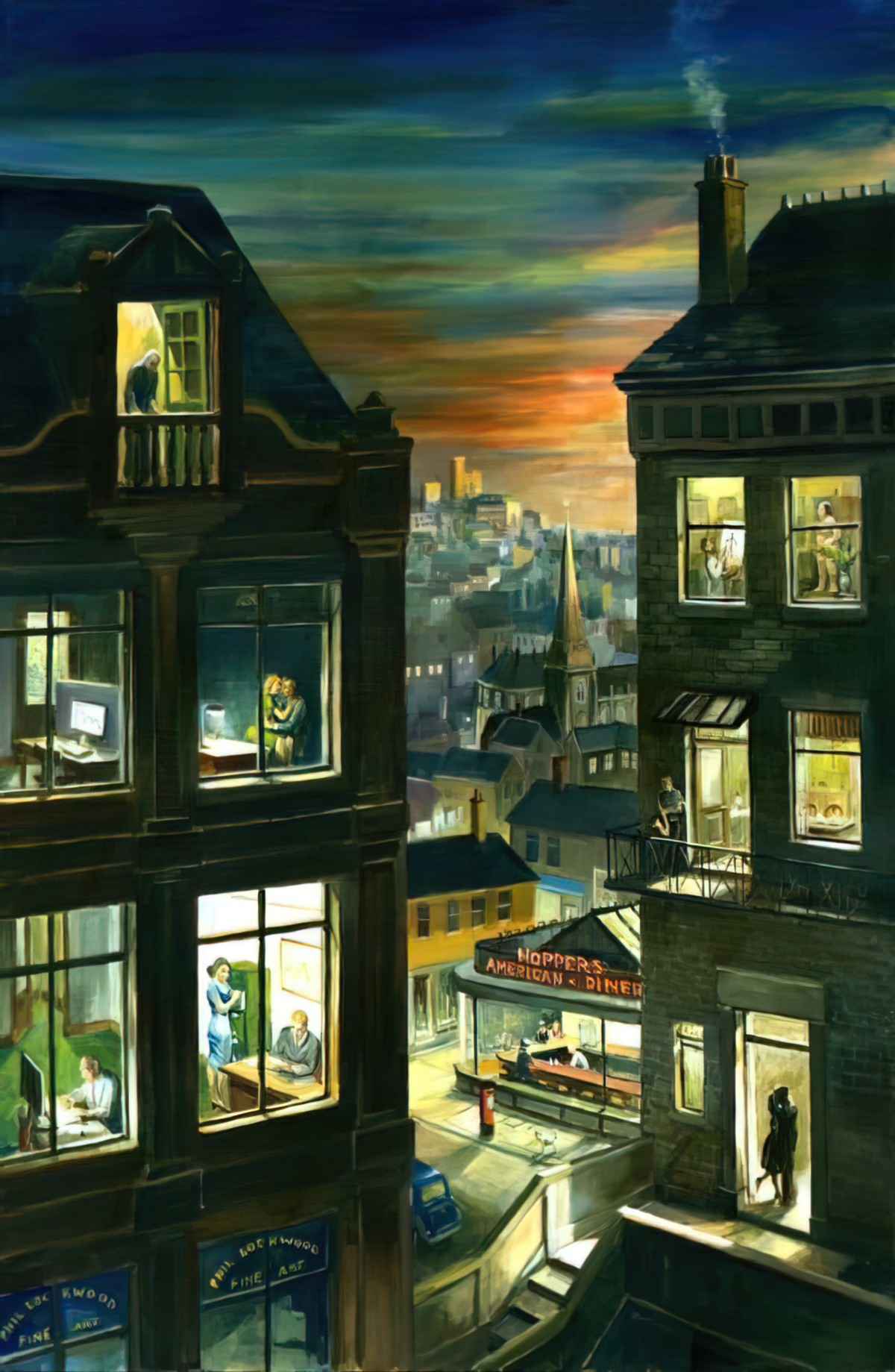

Phil Lockwood, who used to teach art in Sheffield, took Hopper’s famous painting of the lonely American diner and zoomed out to offer a peopled view. Do you think he’s removed the loneliness, or is it still there?

Hopper’s paintings feature spaces–urban exteriors and interiors–that are geometric in their architecture and stone-cold in their apparently stripped-down simplicity. Nevertheless, he imbues these spaces with an uncanny emotionality that reflects complexity, evokes an inanition, and elicits poignancy.

Edward Hopper & Loneliness: Studying “The Loneliness Thing” from The Collector

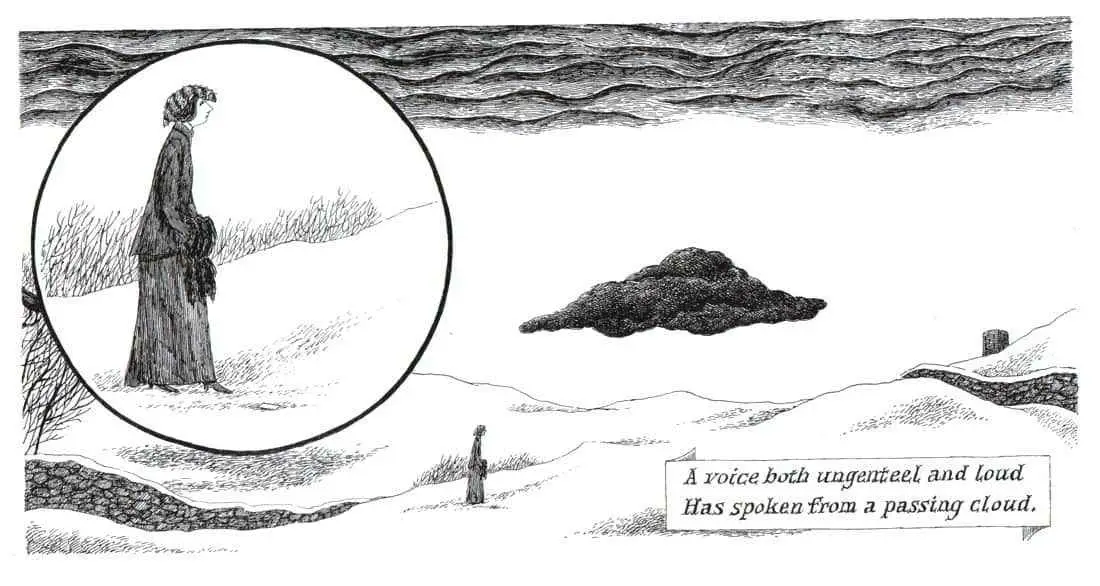

Artist David Inshaw’s image below has a loneliness to it.

Images of young women and girls with their backs turned to the viewer, contemplating a single building in the middle distance are reminiscent of a famous 1948 painting called Christina’s world by painter Andrew Wyeth.

Artists and filmmakers have been creating pastiches of this lonely work since then.

And here are some men alone on an open plain. Archetypal scenes of the Western.

These images feel like the openings to Thomas Hardy novels, which open with an image of a lonely character moving within a scene.

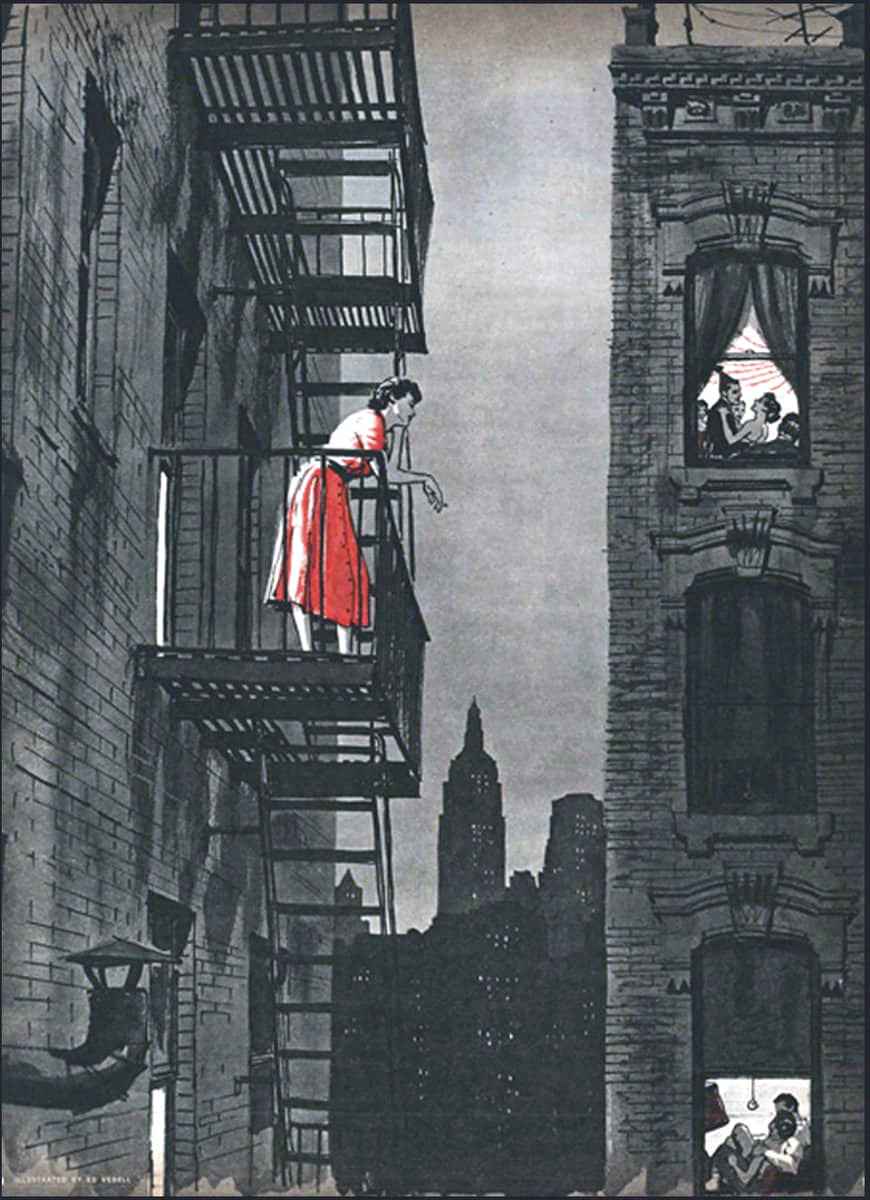

Another artist who depicts loneliness is O. Louis Guglielmi. The painting below includes a girl playing alone, an empty chair on a balcony and a street mostly devoid of decoration.

Alain de Botton doesn’t like the concept of ‘single’ versus ‘in a relationship’. He instead prefers to think of ‘connected’ people and ‘disconnected’ people. This makes more sense because you can still feel lonely even when ‘in a relationship’. Simply having people nearby doesn’t quell loneliness; it really is all about connection.

A CATEGORISATION OF LONELINESS

Not everyone means the same thing when talking about loneliness. Until now, most research on loneliness has focused on social isolation. Yet social isolation and feeling lonely aren’t the same at all. Loneliness most often derives from the experience of feeling like you are different from the people around you and also misunderstood by them.

At The Spinoff, Holly Walker explains the following categories:

- EMOTIONAL LONELINESS: related to the lack or loss of an intimate other

- SOCIAL LONELINESS: feeling unconnected to a wider social network, such as friends, family, and neighbours

- EXISTENTIAL LONELINESS: related to a feeling of lacking meaning and purpose in life.

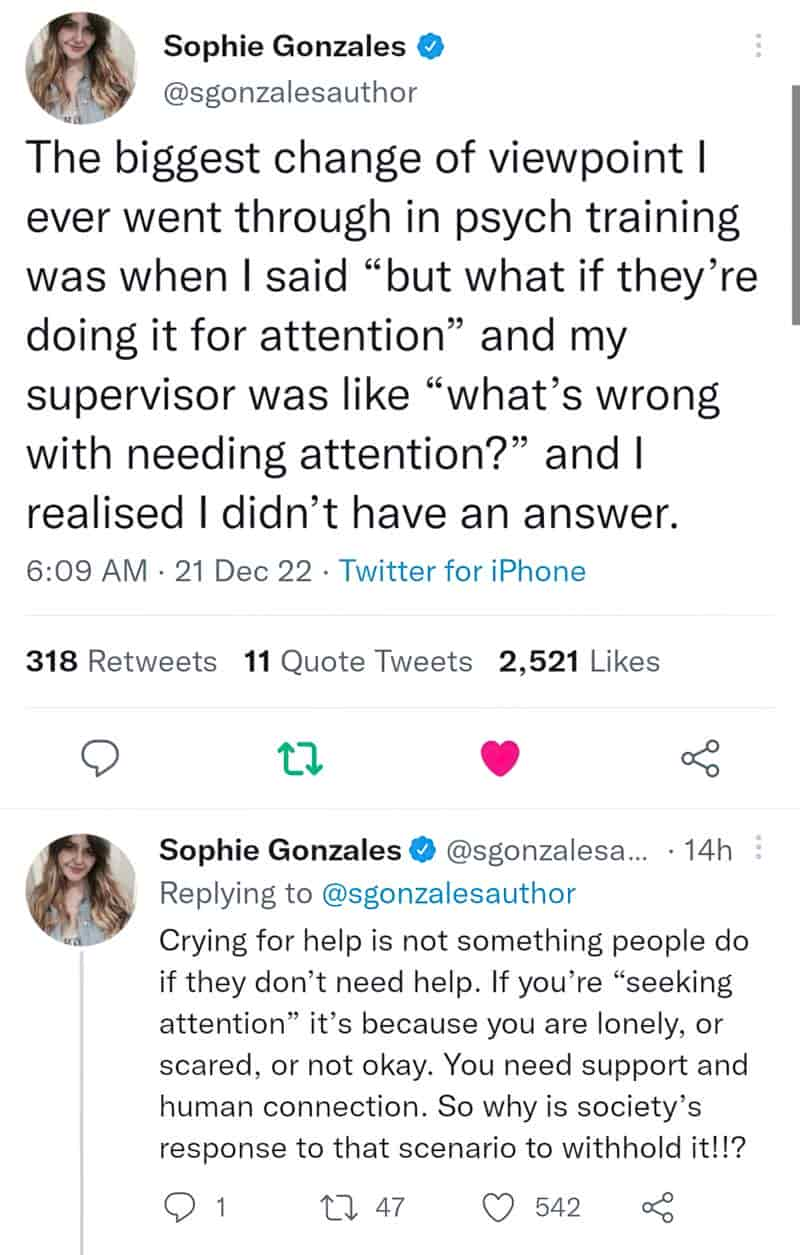

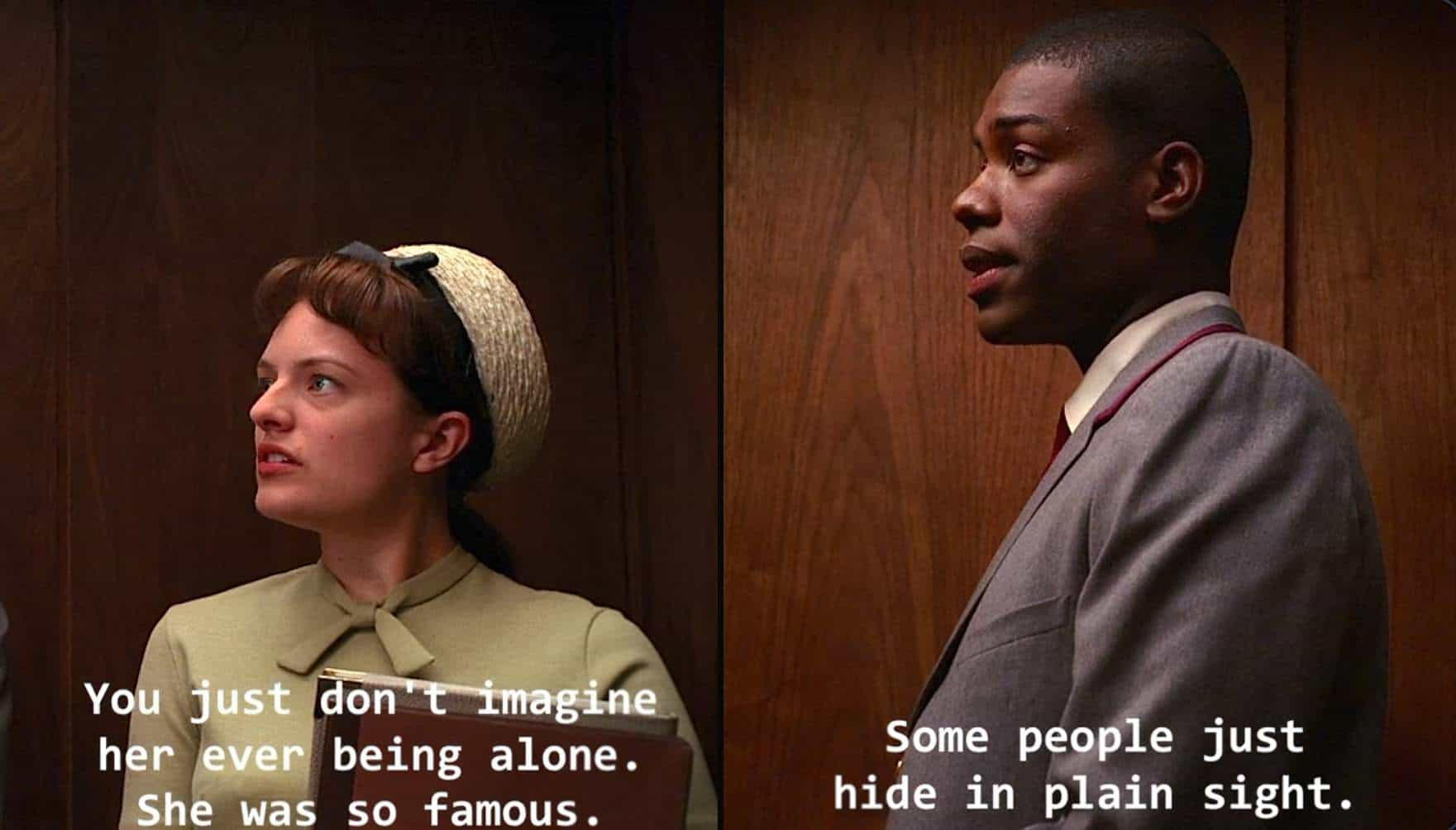

A good example of a story about existential* loneliness: Taxi Driver. Tagline: On every street in every city in this country, there is a nobody who dreams of being a somebody. I believe this particular type of ‘loneliness’ is connected to the feeling that no one is paying attention to you. In stories it frequently leads to a character doing something for attention.

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

On the subcategorisation of social and emotional types of loneliness, a paper entitled “Who are the lonely? A typology of loneliness in New Zealand” breaks social connectedness into four different profiles. One of its authors spoke with Jim Mora on Radio New Zealand:

- HIGH LONELINESS (5.7%). This group comprise the most introverted, emotionally unstable and score poorest in wellbeing. This is a much smaller percentage than some other loneliness studies would suggest, but it depends where researchers draw the loneliness line. Chronic loneliness has a very real effect on health, affecting every kind of mortality, impacting sleep.

- LOW LONELINESS (57.9%). These people don’t really feel lonely at all. This NZ percentage reflects UK and USA statistics.

- APPRECIATED OUTSIDERS (29.1%) Appreciated outsiders receive acceptance from others but feel like social outsiders. These people experience experience and support in the social connections that they do have.

- SUPERFICIALLY CONNECTED (7.2%) The superficially connected are the opposite to ‘Appreciated outsiders’. They have many ‘friends’ but do not enjoy close connections with many or any of them. This group had moderate wellbeing, but ‘appreciated outsiders’ are relatively higher in wellbeing despite greater introversion and neuroticism.

Hannah Hawkins-Elder explains that in reality loneliness is more of a spectrum than a lonely/not-lonely binary because all of us feel lonely at different times. Loneliness forces us to seek social connection, so this is an important emotion, drawing us back into society.

The song Do Do Do (Dansu) feels a bit like an updated version of Eleanor Rigby with its character sketches of loneliness.

LONELINESS AND AGE

Young adults (18-24 year olds) tend to score highest on loneliness in general, followed by the elderly and people with chronic health issues, neurodiversities and similar. British people feel most alone at the average age of 37, which may be quite an arbitrary age.

People look to social media for encouraging loneliness in young people. Social media enables a high quantity of friends but does not encourage authenticity. It’s easier to wear a mask online. We see everyone’s well-lit shop window on the Internet, not their messy storerooms. That said, social media apps are changing in a way which aims to do a better job at fostering authentic connections online, for example by encouraging sharing and chat between smaller groups of people who know each other well.

The 18-24 age is a very liminal, volatile time when we are still forging our own identities. We are quite often leaving home or moving cities, starting new work where we lack confidence. Connecting with others has the prerequisite for finding your people, so we must all understand who we are as people before forging deep, close personal connections. This takes time, and social media aside, may explain why young people are the loneliest demographic. However, this theory requires more research.

Christopher, let’s face it, is gaga over her. Of course, right now their sex life is probably very exciting, and they undoubtedly think that will last, the way new couples do. They think they’re finished with loneliness, too.

This thought causes Olive to nod her head slowly as she lies on the bed She knows that loneliness can kill people — in different ways can actually make you die.

Olive Kitteridge, Elizabeth Strout, p83

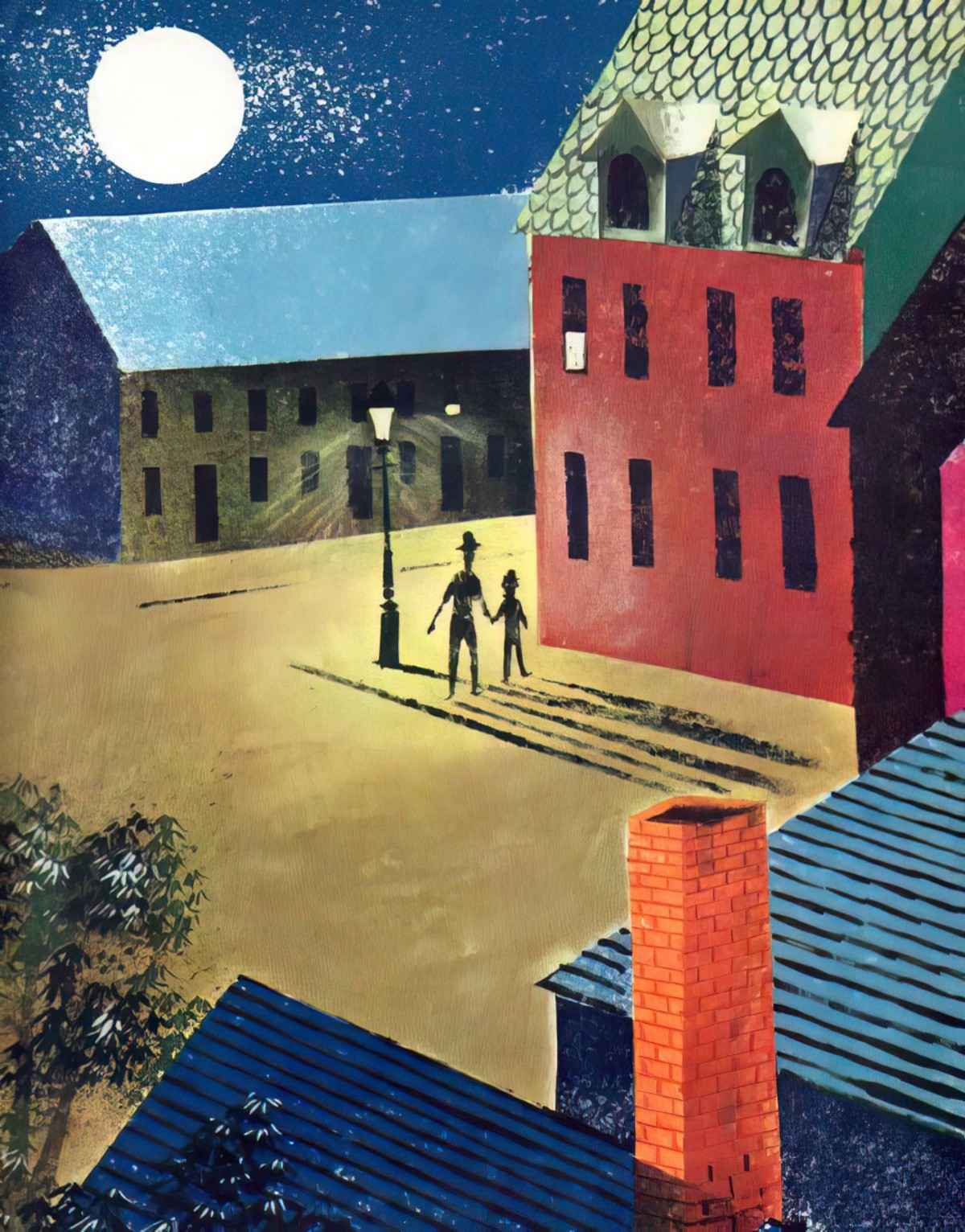

LONELINESS AND THE MOON

In images and stories about loneliness, the moon often features large in the background. This connection goes back a long way. “To the Moon” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) is an ode to the moon, functioning as a symbol of loneliness.

A companion to Shelley’s poem would be the children’s book Owl At Home by Arnold Lobel.

Why might the moon be so connected to loneliness? When we are far from loved ones and look up at the moon we know that those separated from us are also seeing the same object. The moon is one of the few objects which can unite humankind. I speculate that this feeling is related to a psychological experience known as The Overview Effect.

LONELINESS IN FICTION

LONELINESS AND THE IMAGINATION

Other people are so necessary to our mental health that when we have no people around us, we start to hallucinate.

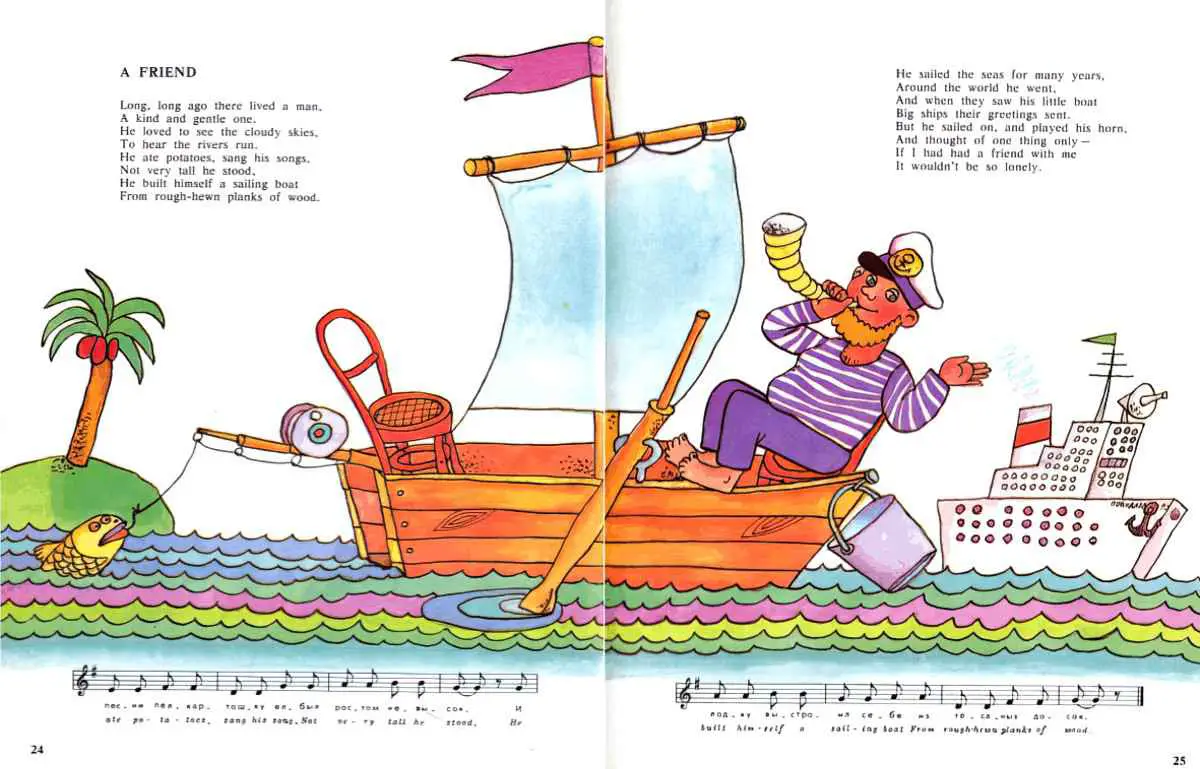

Some of the most compelling descriptions of sensed presences come from lone sailors, mountain climbers, and Arctic explorers who have experienced hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. In one amazing 1895 incident, Joshua Slocum, the first person to circumnavigate the globe in a sailboat singlehandedly, said he saw and spoke with the pilot of Christopher Columbus’s ship The Pinta. Slocum claimed that the pilot steered his boat through heavy weather as he lay ill with food poisoning.

Psychology Today

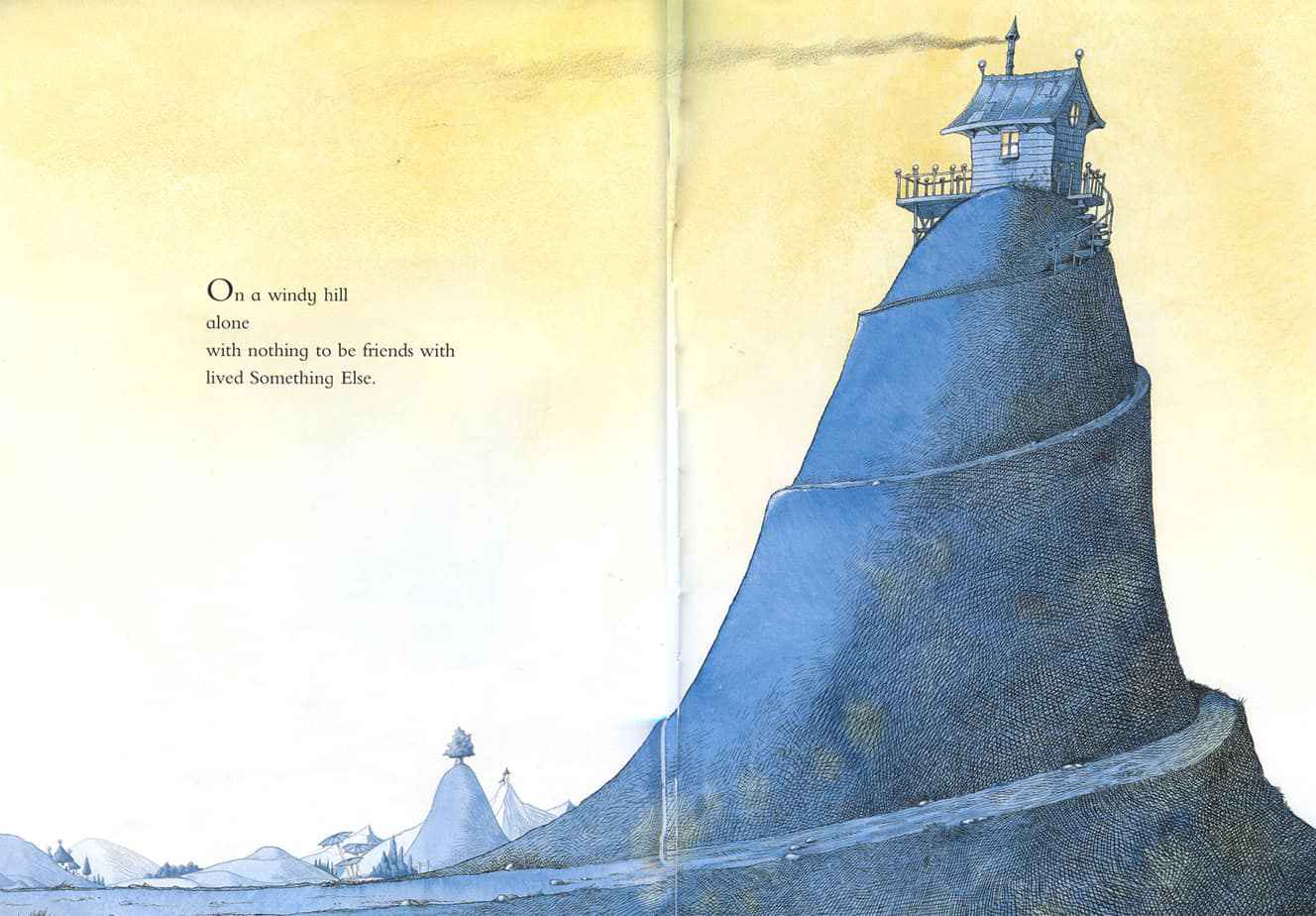

LONELINESS IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

“I’m lonely,” she said.

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

The old gardener pushed his cap back on his bald head and stared at her a minute.

“Art tha’ th’ little wench from India?” he asked.

Mary nodded.

“Then no wonder tha’rt lonely. Tha’lt be lonelier before tha’s done,” he said.

All stories about friendship start from a place of loneliness. Since many children’s stories are about friendship, many start off with lonely main characters. This explains why the trope of the child moving houses is so enduring — everyone is lonely when they move to a new place, faced with the daunting task of starting friendships from scratch.

- Lucy Pevensie is alienated from her older siblings for having a wild imagination but by the end of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe she is a fully included equal.

- Fern is alienated from her farming family The Arables for caring too much about pigs, but soon makes barnyard friends. Initially her mother is worried about this, but the doctor reassures the mother that animal friends are just fine. Whatever it takes to quell the loneliness.

- Picture books are less about loneliness than middle grade literature, though all small children experience a kind of loneliness after being required to sleep alone in their own bed. There exist many Western picture books about that particular experience. Tropes include monsters under the bed and imaginative trips into the night, with carnivalesque guests who may or may not be imaginary. The postmodern picture books of Anthony Browne have a lonely aesthetic (see for example Gorilla), though these picture books tend to appeal to an older audience.

- Somebody Loves You, Mr. Hatch by Eileen Spinelli is a picture book which ostensibly ends happily because a lonely man is appreciated by his wider community despite the revelation that a box of chocolates from a secret Valentine was not meant for him at all. However, I’m not consoled by this ending. Mr Hatch is your classic ‘appreciated outsider’ who is clearly in want of a lover.

There is an unwritten rule in children’s stories that empathetic young characters cannot remain lonely. Lane Moore wrote The Art of Being Alone for adults, and in this interview she talks about all the reading she did as a kid, in which every lonely character ended up with a loving home, from Anne of Green Gables to Matilda. This didn’t reflect Moore’s own childhood experience of loneliness, which continues into adulthood. So perhaps we need revise that unwritten rule.

In his collection Eleven Kinds Of Loneliness, Richard Yates includes a short story about a boy who starts at a new school and becomes ostracised by his peers, helped to fit in by his well-meaning young teacher. So far, so good — you might read it to your child and they’d understand every beat. But why is “Glutton For Punishment” a short story for adults? By the end this young boy has lost the support of his teacher as well as his peers. His loneliness looks set to continue. We don’t accept that ending in stories for children, which must end with hope and at least one friend to quell the interminable loneliness.

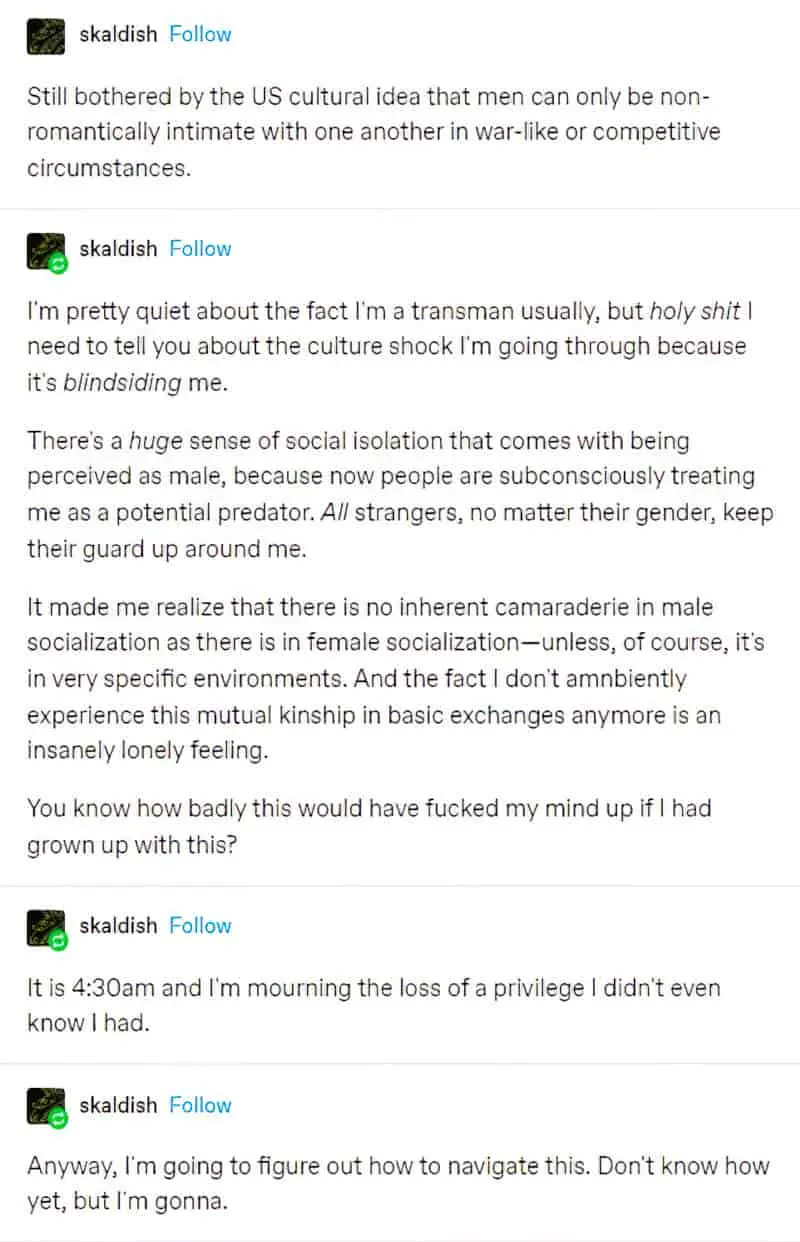

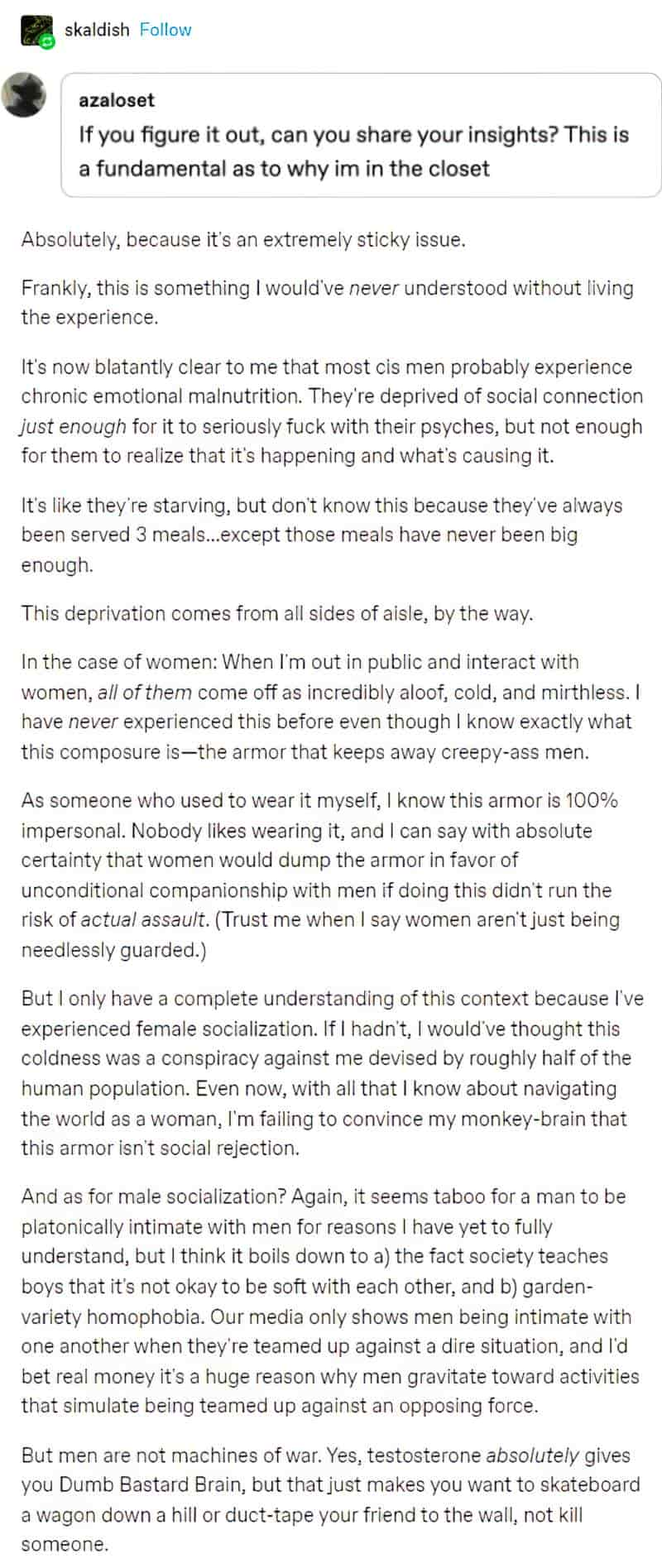

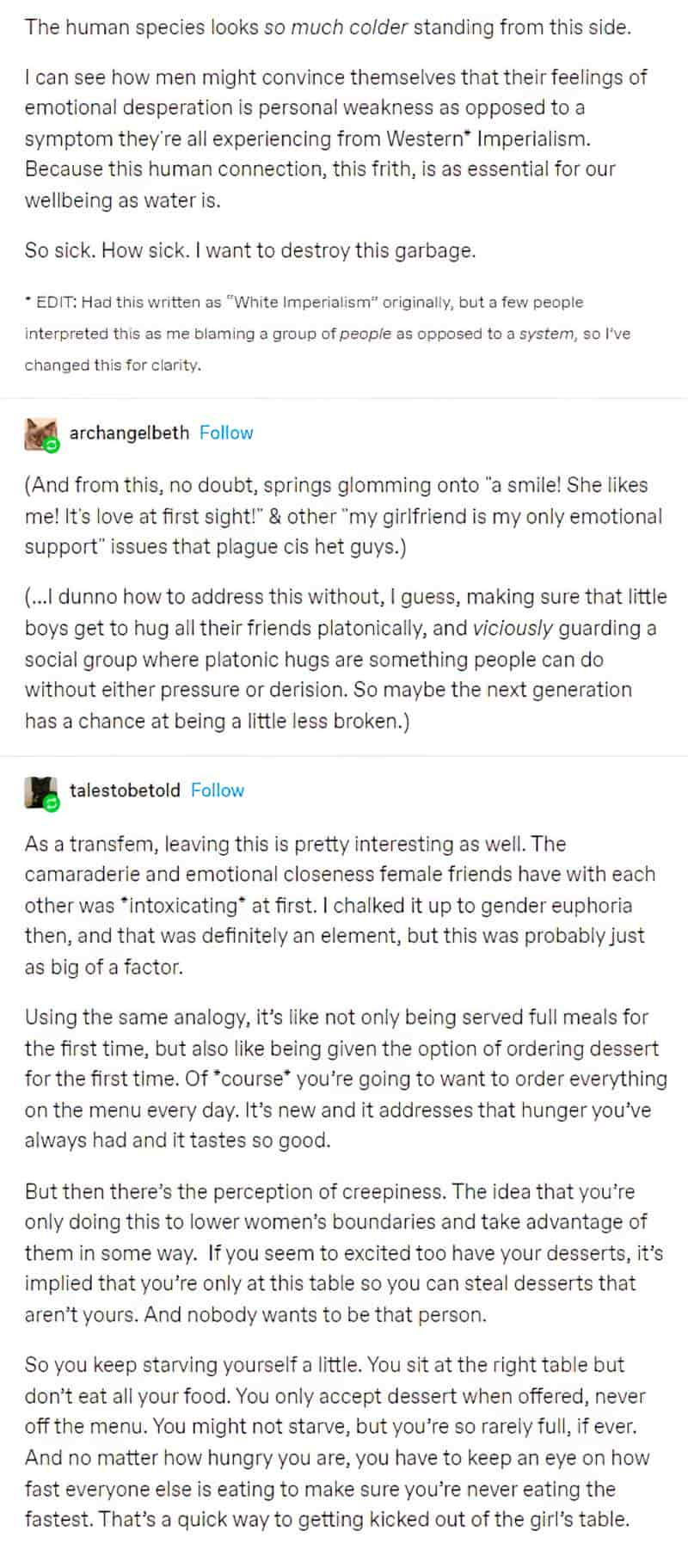

THE LONELINESS OF MEN

LONELINESS AND FICTIONAL MEN

We would rather electrocute ourselves than spend time in our own thoughts. This was demonstrated in a controversial 2014 study in which 67 per cent of male participants and 25 per cent of female participants opted to give themselves unpleasant electric shocks rather than spend 15 minutes in peaceful contemplation. I would like to know why so many more male participants than female participants preferred the electric shocks.

Like children’s stories, many fictional narratives for adults are also about loneliness followed by a happy ending of friendship, though in stories for adults, some stories end on loneliness, with no relief in sight. This marks a difference between the sort of narrative accepted for adult readership versus those accepted for child readership. A story which begins and ends with loneliness is considered a tragedy.

Hud based on the novel by Larry McMurtry is a good example of that kind of tragedy.

Hud is an excellent example of a character who cannot form deep connections because he plays by the rules of toxic masculinity. He cannot form a close connection with a woman because he uses them and assaults them. He cannot form a close connection with his father because he is in direct competition with him for patriarchal control of the farm. Ditto for his nephew, who initially looks up to him.

The Wrestler is another excellent peek into male loneliness, though again, this story is a tragedy.

There’s another type of story which so far predominantly stars men: The story of the man who gets himself a doll. There are two standout examples of this in film: Her and Lars and the Real Girl.

THE SPECIFIC LONELINESS OF THE MIDDLE AGED WOMAN

The “Sex Machine” episode of the Hidden Brain podcast outlines the history of sex objects, going back to Prometheus who created humanity from clay. Likewise, Pygmalion seemed to enjoy fashioning women to his own tastes (he carved a woman out of ivory) and we see the influence of that ancient myth in modern storytelling.

Most middle-aged women are surrounded by people, partly because of the extra caregiving duties experienced by women in midlife (for both children and elderly parents) and also because more women tend to work in people-oriented roles such as nursing and teaching and human resources.

Though she didn’t use this terminology, Irish author Marian Keyes explained on the How To Fail podcast that she feels like an appreciated outsider much of the time, and the main character of Grown Ups is also an appreciated outsider, a fifty-year-old woman who gets social gatherings organised, pays for them, does the dishes at a party and ultimately feels a little like she is buying her friends by performing all this labour.

There’s a teacher archetype who fits into the appreciated outsider category. Richard Yates also includes one of these types of loneliness in his Eleven Kinds of Loneliness collection. “Fun With A Stranger” is the character study of an end-of-career teacher who does not know how to connect with her students, though she tries to with the best of intentions. Though told from the point of view of a student, this woman’s loneliness shines through. A teacher is a prime example of a person surrounded by people, but because of the need for emotional distancing, and due to the intensity of the job, I suspect appreciated outsiders can be found in schools everywhere.

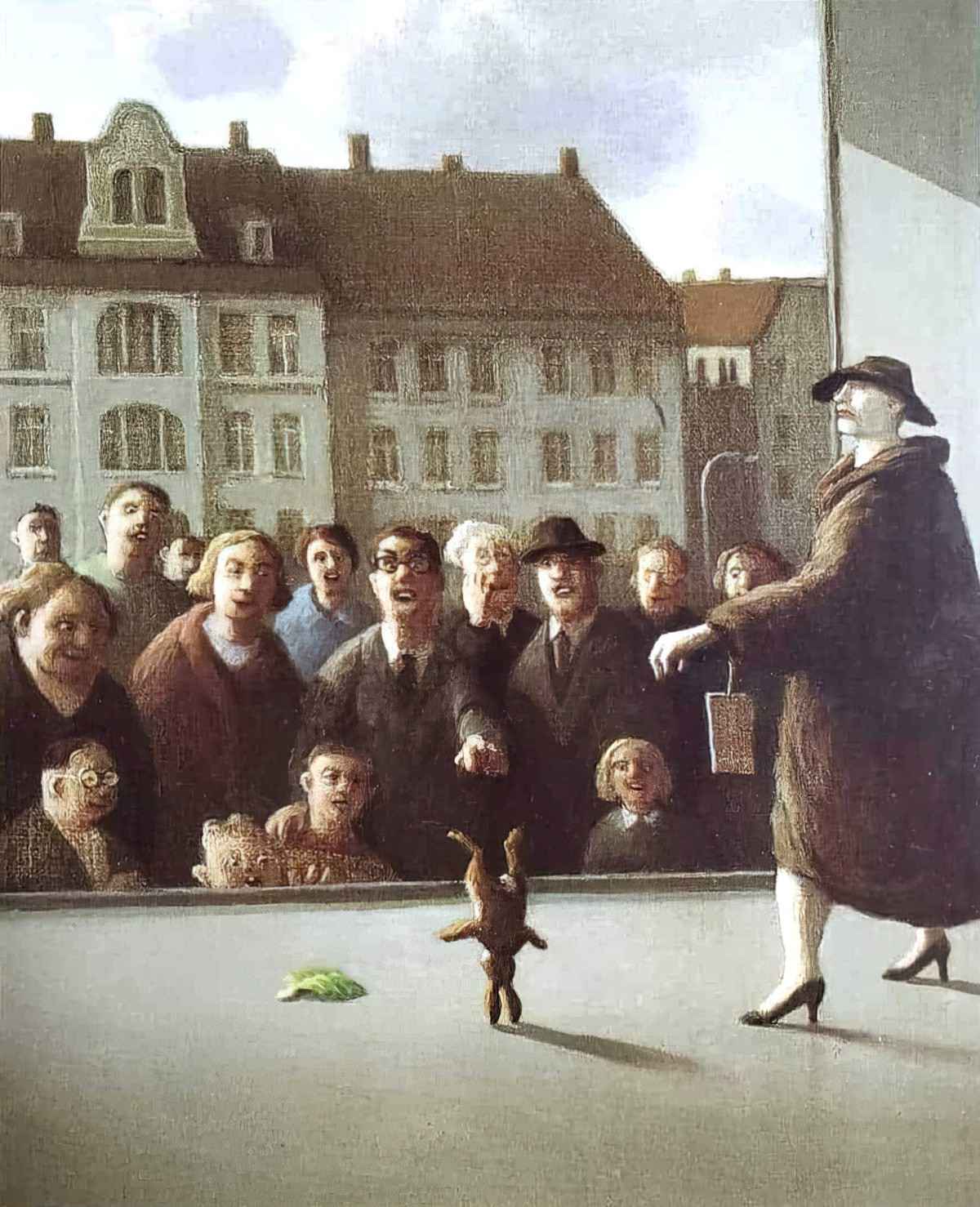

The loneliness of the performer is similar. Surrounded by people, the performer is nonetheless alone on their stage.

A GOOD WINTER BY GIGI FENSTER

The main character of Gigi Fenster’s novel A Good Winter is a lonely middle-aged woman called Olga. Olga makes herself useful to others, taking charge of the body corporate, offering gardening advice. But when she develops an unhealthy obsession with another middle-aged woman in her apartment block, swooping in to offer practical help when the other woman’s daughter experiences personal tragedy, things go downhill.

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman is a popular contemporary novel about a thirty-year-old woman so lonely she attempts to take her own life. The ideological issues of this novel are covered in detail here. (Is there something lonely-sounding about the name Eleanor? Cf. Eleanor Rigby.

Like Olga of Gigi Fenster’s novel, Eleanor misreads social situations and other people’s intentions, creating an ironic gap between narrator and reader.

This is the sort of narration that some readers tend to encode as autism, though autistic women are, to a tee, far more reflective than either of these characters, creepy and comedic in turn. Also, by the time autistic people are fifty years old, there is no statistical difference between the ability of an autistic person and a neurotypical person when it comes to reading other people. (For more on that, see Unmasking Autism by Dr Devon Price.)

Convenience Store Woman

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata is often compared to Eleanor Oliphant. She does something very odd to avoid scrutiny as an unmarried woman nearing middle age. But was she ever really lonely? The Convenience Store Woman partners up with someone she doesn’t even really like, and immediately discovers she is now accepted by mainstream society. No one cares if they’re good together; they only care that she’s partnered. Now they can regard her as Normal.

I’d like to read a story that ends with this particular anagnorisis, and Convenience Store Woman comes pretty close to it:

There are far too many absolute cinnamon rolls who are unhappily alone, and waaaaaaaay too many selfish jerks celebrating golden wedding anniversaries and stinking up R/relationships to ever conclude that romantic love is distributed fairly according to merit.

Captain Awkward

LONELINESS AND KATHERINE MANSFIELD

Katherine Mansfield wrote many lonely women across her short stories. Standouts include:

- Miss Brill, who sits on her on in a park and imagines social connectedness by making up backstories about complete strangers, then returns to her room with the new understanding that she is probably too old to be married and must remain forever alone.

- Linda Burnell of the Prelude trilogy is a mother living in a three-generational household yet remains interminably lonely, perhaps due to post-natal depression or similar. Beryl is unmarried and romantically lonely, though I’d argue she is less lonely than Linda, who is married to hapless Stanley. Beryl knows how to console herself with her imaginative powers.

- Pearl Button is playing alone in her front yard but enjoys a lovely social day after she is whisked away by some Maori women.

- In “The Doll’s House“, two girls are ostracised due to their lower social class. The sisters still have each other, however. We can extrapolate that their exclusion will forge a stronger sisterly bond.

- “A Dill Pickle” is another story about an unwed woman living in genteel poverty, but she is not so lonely that she will marry just anyone.

- “The Escape” features a married couple who live on different emotional planets.

- In “The Tiredness of Rosabel“, Rosabel goes through her life surrounded by people but utterly alone and hungry. This story highlights the inherent loneliness of a large city.

- “Psychology” is a more uplifting story because an unmarried woman seems to have found a way to deal with sexual loneliness, and it involves more than one person.

LONELINESS AND CARSON MCCULLERS

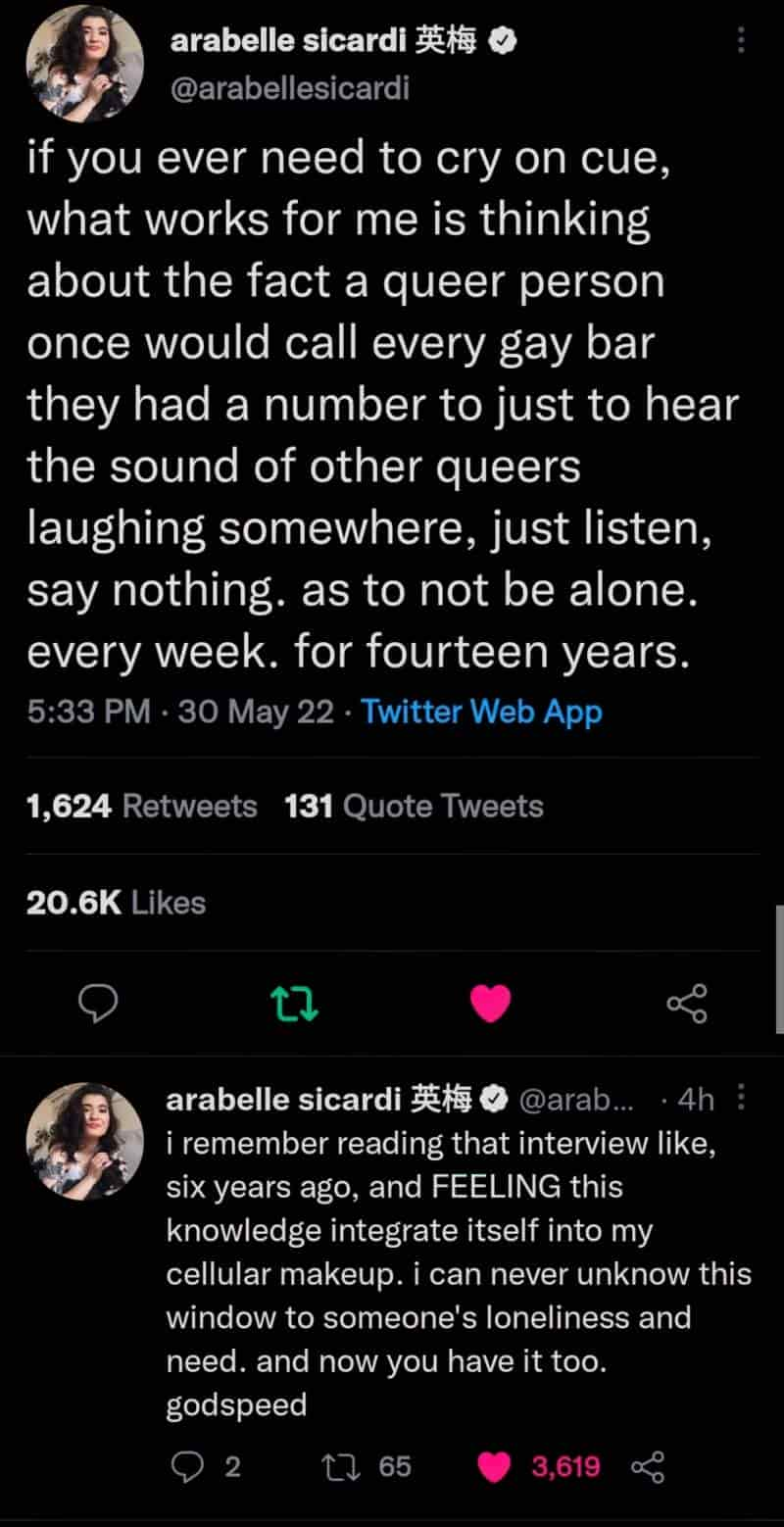

2oth century American writer Carson McCullers is another writer who delved deep into the experience of loneliness across her work. Perhaps the phrase most associated with McCullers is “the we of me”. This comes from the novel The Member of the Wedding and has been especially resonant for the queer community, who commonly watch on as straight peers and friends get on with the business of living their straight lives, partnering up and settling down, leaving queer people behind to forge our own paths.

“The trouble with me is that for a long time I have just been an I person. All people belong to a We except me. Not to belong to a We makes you too lonesome.”

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

She was afraid of these things that made her suddenly wonder who she was, and what she was going to be in the world, and why she was standing at that minute, seeing a light, or listening, or staring up into the sky: alone.

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

There are all these people here I don’t know by sight or by name. And we pass alongside each other and don’t have any connection. And they don’t know me and I don’t know them. And now I’m leaving town and there are all these people I will never know.”

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

McCullers touches on the link between loneliness and solipsism:

“Listen,” F. Jasmine said. “What I’ve been trying to say is this. Doesn’t it strike you as strange that I am I, and you are you? I am F. Jasmine Addams. And you are Berenice Sadie Brown. And we can look at each other, and touch each other, and stay together year in and year out in the same room. Yet always I am I, and you are you. And I can’t ever be anything else but me, and you can ever be anything else but you. Have you ever thought of that? And does it seem to you strange? ”

Carson McCullers, Member Of The Wedding

Carson also considered love no salve for loneliness. Love can sometimes exacerbate it.

First of all, love is a joint experience between two persons — but the fact that it is a joint experience does not mean that it is a similar experience to the two people involved. There are the lover and the beloved, but these two come from different countries. Often the beloved is only a stimulus for all the stored-up love which had lain quiet within the lover for a long time hitherto. And somehow every lover knows this. He feels in his soul that his love is a solitary thing. He comes to know a new, strange loneliness and it is this knowledge which makes him suffer. So there is only one thing for the lover to do. He must house his love within himself as best he can; he must create for himself a whole new inward world — a world intense and strange, complete in himself. Let it be added here that this lover about whom we speak need not necessarily be a young man saving for a wedding ring — this lover can be man, woman, child, or indeed any human creature on this earth.

Carson McCullers

She wished there was some place where she could go to hum it out loud. Some kind of music was too private to sing in a house cram fall of people. It was funny, too, how lonesome a person could be in a crowded house.

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter

The following observation only seems more timely today than when McCullers was writing it, now that more people go by identity labels (due to neurodivergence, queerness, disability etc.):

After the first establishment of identity there comes the imperative need to lose this new-found sense of separateness and to belong to something larger and more powerful than the weak, lonely self. The sense of moral isolation is intolerable to us.

Carson McCullers, The Mortgaged Heart: Selected Writings

For you see, when us people who know run into each other that’s an event. It almost never happens. Sometimes we meet each other and neither guesses that the other is one who knows. That’s a bad thing. It’s happened to me a lot of times. But you see there are so few of us.”

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

McCullers also understood the lonely concept of fernweh:

It is a curious emotion, this certain homesickness I have in mind. With Americans, it is a national trait, as native to us as the roller-coaster or the jukebox. It is no simple longing for the home town or country of our birth. The emotion is Janus-faced: we are torn between a nostalgia for the familiar and an urge for the foreign and strange. As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.

Carson McCullers

LONELINESS AND ALICE MUNRO

A well-known feature of Alice Munro’s writing: She writes a lot about carers. And carers are the loneliness demographic, alongside the people they care for.

According to experts, the group is one of the poorest, loneliest, and most overworked cohorts in the country.

The latest national Carer Wellbeing Survey published this month collected responses from more than 5,000 carers.

It found they were almost twice as likely to report having low wellbeing compared to other Australians, and were much more likely to report feeling lonely regularly — at 38.6 per cent, compared with 19.3 per cent of non-carers.

National survey shows unpaid carers’ wellbeing continues to decline, and advocates say it’s time they got a break, Australia’s ABC

Homesickness: Culture, Contagion, and National Transformation in Modern China

Carlos Rojas‘s new book is a wonderfully transdisciplinary exploration of discourses of sickness and disease in Chinese literature and cinema in the long twentieth century. As its title indicates, Homesickness: Culture, Contagion, and National Transformation in Modern China (Harvard University Press, 2015) focuses particularly on what Rojas calls “homesickness,” a condition wherein “a node of alterity is structurally expelled from an individual or collective body in order to symbolically reaffirm the perceived coherence of that same body.”

Sickness and disease, here, are not just signs of weakness and instability, but are also potential sources of dynamic transformation. In three major parts of the book set in three years – 1906, 1967, and 2006 – Rojas places immunology, biomedicine, literature, and film into a conversation that spans the work of Richard Dawkins; writers Liu E, Ng Kim Chew, Zeng Pu, Jin Tianhe, Lu Xun, Hu Fayun, Yan Lianke, and Yu Ha; immunologist Dr Metchnikoff; and directors King Hu, Tsai Ming-liang, and Jia Zhangke (among many others).

In each case, Homesickness contextualizes literary work within a broader historical context that allows readers to understand the relationships between contemporary tropes – or memes – of Self and Other as they manifest in concerns about healthy and sick bodies at many different scales. It’s well worth reading for those interested in Chinese literature or film, the history and literature of biomedicine, and/or the ways that discourses of immunology and modernity have mutually shaped one another.

New Books Network

McCullers believed American loneliness was a special kind. They called loneliness “the great American malady”:

The loneliness of Americans does not have its source in xenophobia; as a nation we are an outgoing people, reaching always for immediate contacts, further experience. But we tend to seek out things as individuals, alone. The European, secure in his family ties and rigid class loyalties, knows little of the moral loneliness that is native to us Americans.

Carson McCullers

I think we look for the differences in people because it makes us less lonely.

Carson McCullers

Once you have lived with another, it is a great torture to have to live alone.

Carson McCullers, The Ballad of the Sad Café and Other Stories

I am not meant to be alone and without you who understands.

Carson McCullers

In his face there came to be a brooding peace that is seen most often in the faces of the very sorrowful or the very wise. But still he wandered through the streets of the town, always silent and alone.

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter

Everyone is very busy denying the last time they were lonely, but trust me, it happens. It isn’t just being a solo act, though that contributes; I know women and men who stand in their back yards, safe in the bosom of their family, at the height of their careers, and stare up into the old reliable silver-maple tree, mentally testing its capacity to hold their weight.

“Glory Goes and Gets Some” by Emily Carter

- 123 Ambrose and His Orchestra — I’m So Alone With The Crowd (YouTube)

- Rex Allen — I’m So Alone With The Crowd (c. 1945) (YouTube)

The song “Main Girl” by Charlotte Cardin is about the specific loneliness of being the ‘other’ girl rather than a guy’s ‘main girl’. Stories generally feature, centre and create empathy for ‘the main girl’, and Cardin wanted to tell the other side for a change.

So often in books, or in movies, one character looks at another character and understands in a precise way what that person is feeling. So often in real life, one person wants to be understood, but obscures her feelings with unrelated words and facial expressions, while the other person is trying to remember whether she did or didn’t turn off the burner under the hard-boiled eggs.

Criss Cross by Lynne Rae Perkins

FURTHER READING

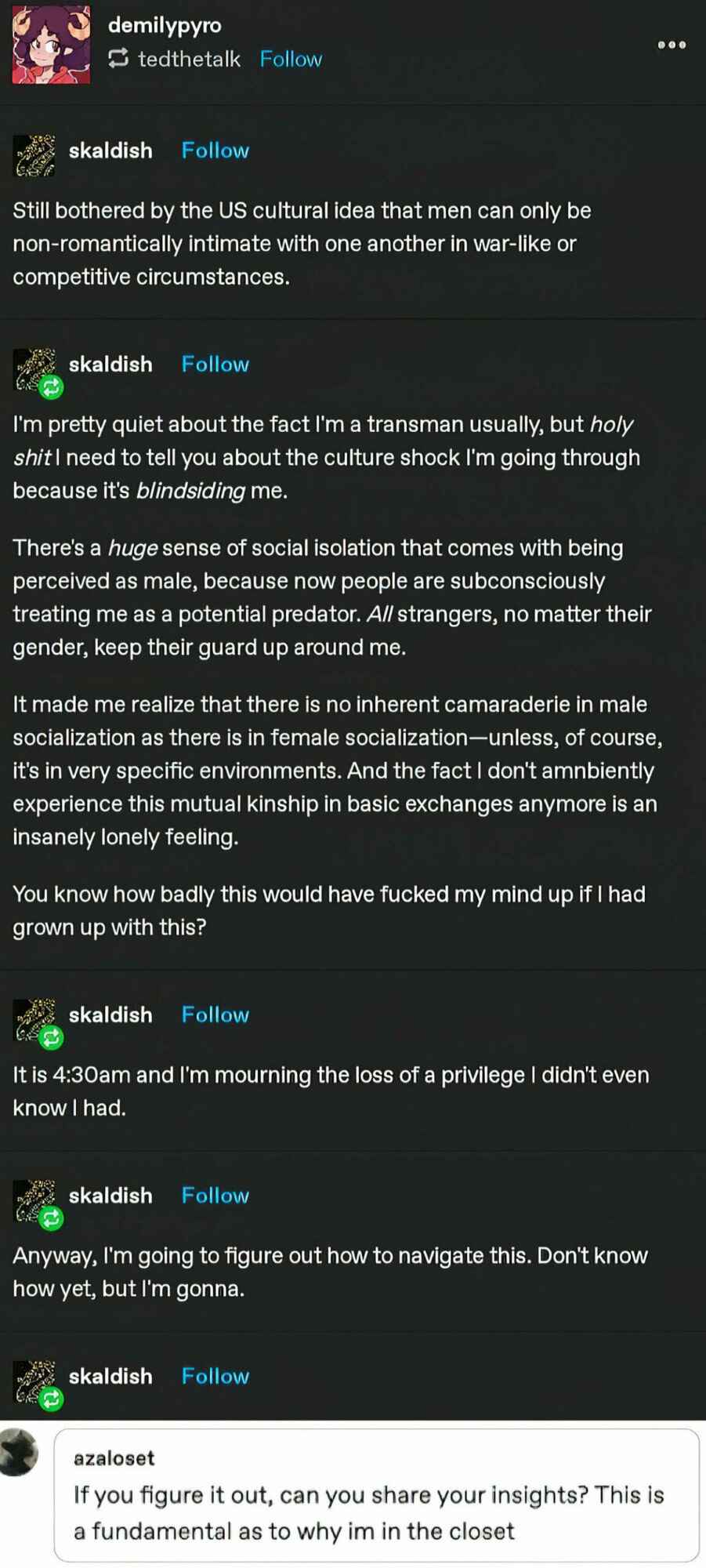

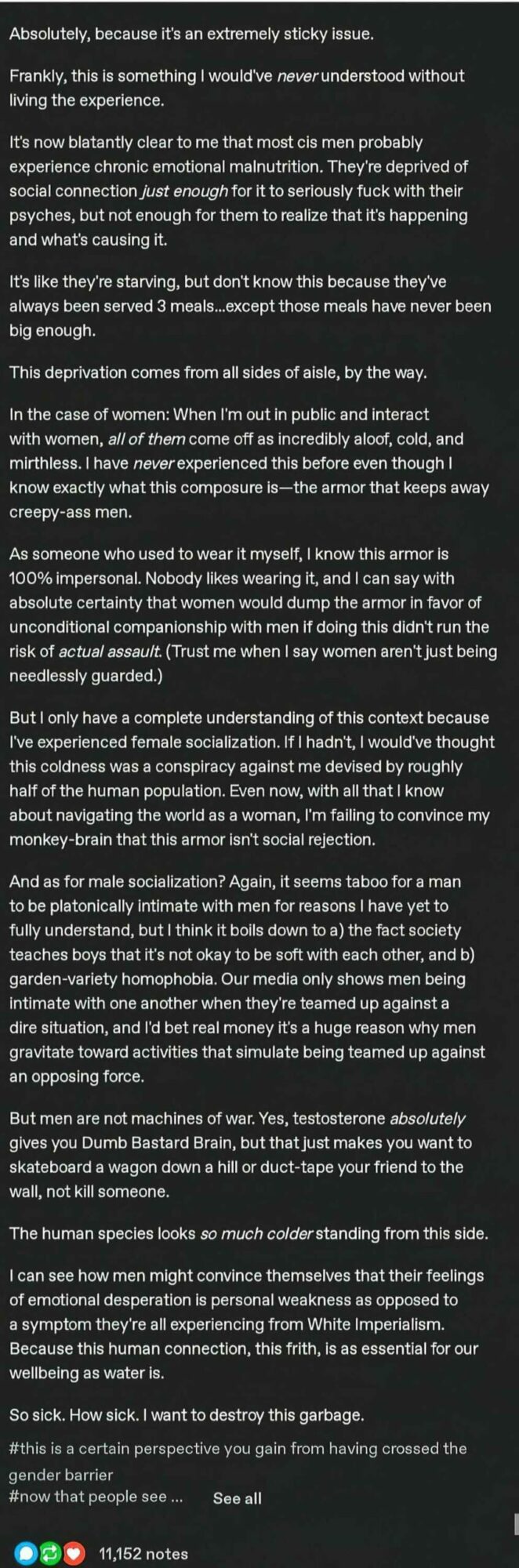

Trans men are well-placed to speak to the specific loneliness of men compared to women, as the cultures are different.

“And there is a dignity in people; a solitude; even between husband and wife a gulf; and that one must respect, thought Clarissa, watching him open the door; for one would not part with it oneself, or take it, against his will, from one’s husband, without losing one’s independence, one’s self-respect—something, after all, priceless.”

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

“Modern life seems set up so that we can avoid loneliness at all costs, but maybe it’s worthwhile to face it occasionally. The further we push aloneness away, the less are we able to cope with it, and the more terrifying it gets. Some philosophers believe that loneliness is the only true feeling there is. We live orphaned on a tiny rock in the immense vastness of space, with no hint of even the simplest form of life anywhere around us for billions upon billions of miles, alone beyond all imagining. We live locked in our own heads and can never entirely know the experience of another person. Even if we’re surrounded by family and friends, we journey into death completely alone.”

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

UNSEEN, UNHEARD, UNDERVALUED BY JANINA SCARLET

Have you ever felt like you’re shouting into the void for someone to just see you and to acknowledge that you exist, that you have value, that you are loved?

That feeling-like no one can really see who you are, like no one really gets it, that’s loneliness. The truth is everyone feels lonely. It is a universal emotion, one we all experience at one point or another, but we have also been made to feel ashamed, oppressed and stigmatised about experiencing it.

Being seen means that someone notices you and includes you.

Being heard means to be listened to without interruption, gaslighting or invalidation, but rather with compassion and understanding.

Being valued means being respected and treated with compassion and kindness. When all three of these needs are met, we experience a sense of belonging.

Human beings need more than access to food, sleep and water to survive. We also need to feel that sense of belonging, understanding and support.

FRIENDSHIP LOVE LANGUAGES

A lot of times we think of love languages as between intimate partners. I included a chapter which talks about friendship love languages, which is [about] how we want to be received and supported by our friends, let’s say when we’re going through a hard time.

Some people genuinely want advice when they’re struggling. Some people want someone to listen and validate them or maybe to come over and keep them company or send them a present for instance, to say, “Hey, I’m thinking of you. Here’s a care package.” I encourage people to think about what they need in their difficult time and to let their friends know so there can be this conversation … with their chosen family.

Unseen, Unheard, Undervalued with Janina Scarlet published Wednesday 18 October 2023 at Psychologists Off The Clock podcast

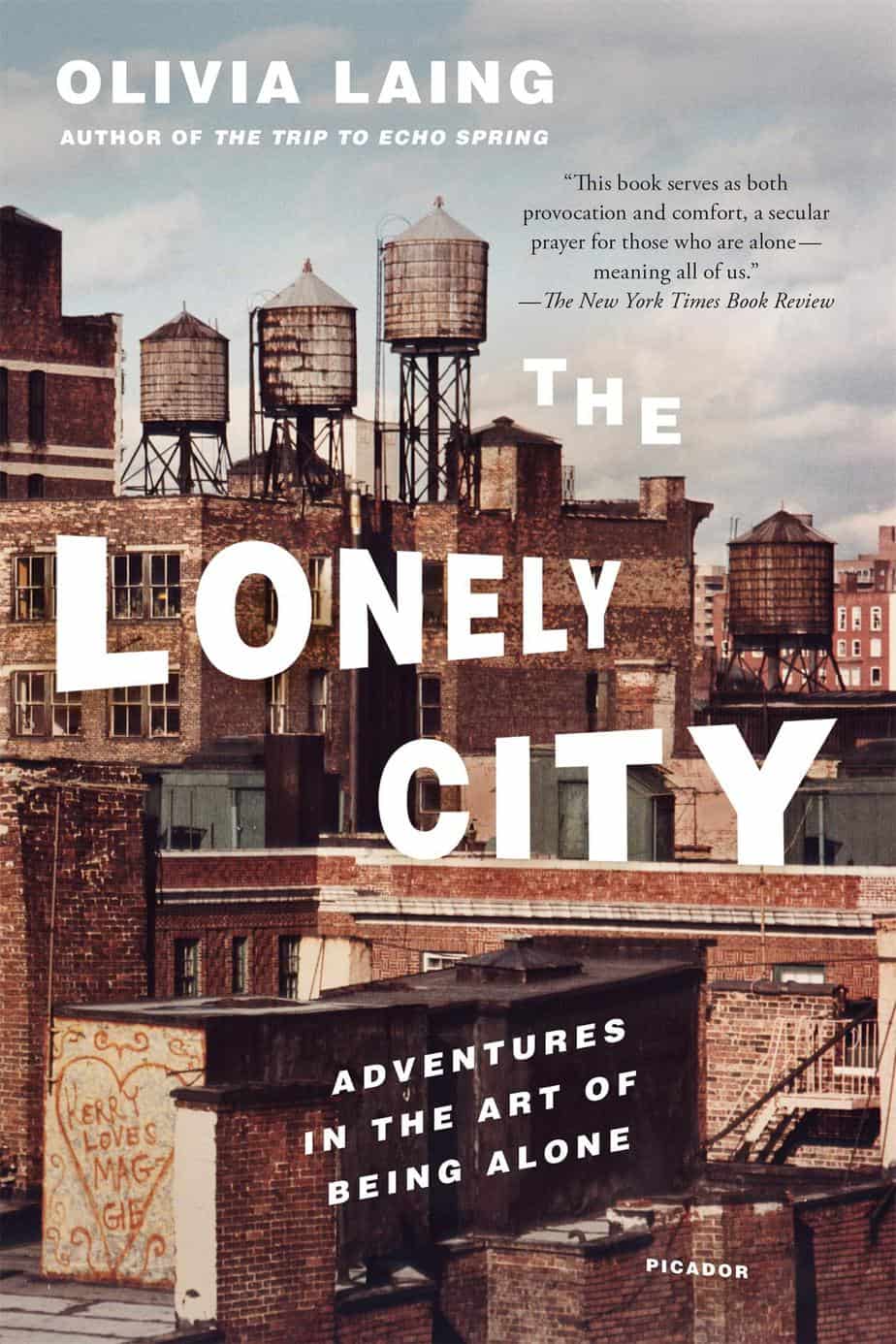

When Olivia Laing moved to New York City in her mid-thirties, she found herself inhabiting loneliness on a daily basis. Increasingly fascinated by this most shameful of experiences, she began to explore the lonely city by way of art.

Moving fluidly between the works and lives of some of the city’s most compelling artists, Laing conducts an electric, dazzling investigation into what it means to be alone, illuminating not only the causes of loneliness but also how it might be resisted and redeemed.

22 year old Jena Chung plays the violin. She was once a child prodigy and is now addicted to sex. She’s struggling a little. Her professional life comprises rehearsals, concerts, auditions and relentless practice; her personal life is spent managing family demands, those of her creative friends, and lots of sex. Jena is selfish, impulsive and often behaves badly, though mostly only to her own detriment. And then she meets Mark – much older and worldly-wise – who bewitches her. Could this be love?

When Jena wins an internship with the New York Philharmonic, she thinks the life she has dreamed of is about to begin. But when Trump is elected, New York changes irrevocably and Jena along with it. With echoes of Frances Ha, Jena’s favourite film, truths are gradually revealed to her. Jena comes to learn that there are many different ways to live and love and that no one has the how-to guide for any of it – not even her indomitable mother.

A Lonely Girl is a Dangerous Thing explores the confusion of having expectations upturned, and the awkwardness and pain of being human in our increasingly dislocated world – and how, in spite of all this, we still try to become the person we want to be.

The Haunting of Shirley Jackson: Emily Alford on the hazards of loneliness seen in Shirley Jackson’s books and the ways recent film adaptations have missed the mark.

WORDS RELATED TO LONELINESS

Adronitis

Frustration with how long it takes to get to know someone.

Anecdoche

A conversation in which everyone is talking but no one is listening.

Exulansis

The tendency to give up trying to talk about an experience because people are unable to relate to it.

Kenopsia

The eerie, forlorn atmosphere of a place that is usually bustling with people but is now abandoned and quiet.

Mauerbauertraurigkeit

The inexplicable urge to push people away, even close friends who you really like.

Nodus Tollens

The realisation that the plot of your life doesn’t make sense to you anymore.

Onism

The frustration of being stuck in just one body, inhabiting only one place at a time.

SPECTACLE

The spectacle is simply the common language of this separation. Spectators are linked solely by their one-way relationship to the very center that keeps them isolated from each other. The spectacle thus reunites the separated, but it reunites them only in their separateness.

Guy Debord

FURTHER RESOURCES ON LONELINESS

Unseen, unheard, undervalued – have you ever felt like that? As our guest this week, Dr. Janina Scarlet, a licensed clinical psychologist, points out, these feelings, while understandable, can be overcome. In Janina’s mission to de-stigmatize loneliness and help people connect and support one another, she authored the book ‘Unseen, Unheard, Undervalued: Managing Loneliness, Loss of Connection and Not Fitting in’ which serves as the backdrop for the conversation in this episode. You’ll hear how to combat loneliness by understanding its dimensions, talking more about our experiences with loneliness, and seeking emotional support and self-compassion. Janina also offers many helpful tips, from finding and cultivating a ‘chosen family’ who truly sees, hears, and values you to transforming how you feel and react to shame.

Unseen, Unheard, Undervalued with Janina Scarlet, Psychologists Off The Clock podcast

Header illustration: Richard Riemerschmid In The Countryside 1895