“The Loaded Dog” (1901) is an Australian short story by Henry Lawson. The story is so memorable, the main imagery of a dog with a firecracker in its mouth has become Australian larrikin iconography. Henry Lawson died in 1922, so his work is now in the public domain.

Below is an example of the phrase “loaded dog” in use, from 2022 Australian media. This article describes the retirement of a conservative politician, who will be leaving a ‘colourful’ career behind him:

“Like a dog with a firecracker in its mouth’: NSW politics ponders life without David Elliott

“He’s like a dog with a firecracker in its mouth, you’re never sure which way it’s all going to go,” a Liberal source said, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

The Sydney Morning Herald October 23, 2022

Now let’s revisit the famous story itself. Ah, this a story of its time. I can’t find it funny mainly because of the animal cruelty involved. This level of cruelty can even be seen in Australian children’s books of similar era e.g. The Cider Duck.

Further content note for racist language typical of the era and male intimate partner violence used for comedic ends. (This is why I am no great fan of ‘larrikin culture’.)

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE LOADED DOG”

- Three men are hoping to find gold at Stony Creek. (There are a number of places called Stony Creek dotted around Australia.)

- The men are called Dave, Jim and Andy. Lawson gives us last names to make them seem like real blokes. There are three because outlandish yarns by convention have three characters in them. Cf. all those jokes which start with, “There was an Englishman, a Scotsman and an Irishman…” or “There was a doctor, a lawyer and a priest…” Like the characters in those jokes, Dave, Jim and Andy are low mimetic heroes (to use the terminology of Northrop Frye). They’re like you and me, but a little more hapless, and perhaps a little less smart.

- The three men are archetypes of white bushmen eking out a living at the Australian fin de siecle, though this story was written then, about a legend which supposedly happened years earlier.

- Like the economically unstable everywhere, these gold prospectors are sure they’ll strike it rich one day. Their efforts in locating a gold seam are based on nothing but rumour and optimism. They are focusing on a largely dried up creek, with nothing but muddy puddles. Such is their comically desperate circumstance. (Notice the irony: This story itself is based on nothing but rumour. The rumour-inside-a-rumour story structure winks at the reader. Believe this if you dare.)

- But the hapless heroes get side-tracked. Having no luck with gold, they occasionally get a nibble of fish. (What’s a tall story without fish?) This bit of luck keeps them fishing. Andy in particular enjoys sitting by a muddy puddle dangling a line. The infrequent bite is exactly how gamification works, by the way. Casinos can be addictive precisely because of regular, small rewards. With no reward whatsoever (in this story the gold), these three men lose motivation. So they turn their attention to fishing. They can at least swap fish for meat at the local butcher’s.

- Motivation increases when revenge becomes part of it. One type of fish is especially painful. A cat-fish injures Dave. The pain keeps him awake for two nights. So he decides to ‘blow up the fish.’

- Dave makes a bomb of blasting-powder and strong calico. (Henry Lawson explains the making of this bomb in great detail.)

- Then he makes some dinner. Lamb chops, of course (these days the most expensive meat).

- At this point Henry Lawson introduces the retriever dog, ‘or rather an overgrown pup, a big, foolish, four-footed mate, who was always slobbering round them and lashing their legs with his heavy tail that swung round like a stock-whip.’ Importantly (for the set-up — see below): ‘He’d retrieve anything.’

- But Henry Lawson needs to put some space between describing the dog ‘who’d retrieve anything’ and the gag in which he retrieves the bomb. So he next describes a dead cat which the dog once brought in to camp.

- A slapstick chase scene ensues in which the foolish retriever is chasing the three men with a lit fuse in its mouth.

- Of course, writers are told not to kill a dog. Henry Lawson doesn’t blow up this dog. He introduces an expendable dog — a Scarface Claw figure who lives under the hotel (shanty) kitchen and has a notorious reputation for aggression. This dog is described as ‘a vicious yellow mongrel cattle-dog sulking and nursing his nastiness’. (A shanty is a small, crudely built shack.)

- Lawson blows that dog up instead. But he leaves out the gory details. In fact, he leaves out the details altogether. This story is written in colloquial language, designed as a tall tale, to be told around campfire. Where there’s a dash, replace with explosive body language.

- Notice how the area is full of dogs running around. It’s easy to forget Australia was once like this, even in towns. New Zealand was, too, by the way, because speaking of Hairy Maclary, Lynley Dodd wrote that children’s picture book based on a pack of real neighbourhood pet dogs who used to roam Wellington when she lived there in the 1970s. Both New Zealand and Australia have since stopped that from happening, with heavy fines for owners who let their dogs roam free. (That said, in Outback Australia you can sometimes live by your own rules.)

- The story concludes by jumping forward in time. ‘For years afterwards…’ Dave is now a legend.

- More casual violence concludes the story. One of the other dogs went blind and is clearly traumatised by the smell of gunpowder. A woman starts crying and her husband threatens to ‘lam the life out of’ her. He is threatening to beat her up if she doesn’t stop crying. Henry Lawson presents this scene as part of the comedy, and offers contemporary readers some insight into the casual and expected male violence of the era.

WHAT IS BLASTING-POWDER?

The use of explosives in mining goes back to the year 1627.

Blasting-powder is a more modern form of gunpowder. It’s not actually a powder, but consists of hard pellets about the size of bean seeds. Blasting-powder is a low or heaving explosive, which means it reacts by very rapid burning rather than by sudden detonation.

Because of these properties, blasting-powder found its main use in timber splitting, since there is less chance of timber shattering and splintering when blown up with blasting-powder. It has also been used for splitting monumental stone.

It lights easily and does not require a detonator.

When ignited in the open, blasting-powder produces a sudden flash and a cloud of smoke but it does not result in a big bang. Used properly, blasting-powder must be well-tamped into a confined space.

When pretty much every man smoked tobacco, it was dangerous to leave lying around. If you spilled any, you were cautioned to sweep it up right away.

If you want to desensitise blasting-powder, get it wet. The stuff is highly sensitive to moisture, including moisture from the air. The men in this story use beeswax to keep it watertight, which lampshades that issue for readers who know about blasting-powder and water.

Australians — mainly farmers — could freely buy blasting-powder throughout the 20th century, though after the war stores needed licences to sell it. It was up to the storeman to decide whether his customer would be using it properly. He was only supposed to sell you the amount you would need for a specific task, and no more. The customer was required to provide a suitable receptacle and to protect the explosives against theft and fire hazard.

These days in Australia if you want to blow things up you need a Blasters Licence, a National Police Clearance Certificate less than three months old and familiarity with the Explosives Regulations of 2011.

Not the blokes in this story, though. The safety fuse had been invented in 1831, but obviously there’s no ‘safety fuse’ on the calico sausage of blasting-powder these fellows knocked together.

There’s an historic black powder mill in Cairnlea, Victoria — Melbourne’s West. There used to be a couple more black powder mills in that area, but that one is the only mill left (for tourism purposes).

SET-UPS IN COMICAL STORIES

When we talk about ‘serious’ stories, we use words like foreshadowing. As part of its definition, foreshadowing works at the level of metaphor.

I rarely analyse comical short stories, so “The Loaded Dog” provides good opportunity to take a closer look at the difference between two related but different aspects of story: foreshadowing and set-up.

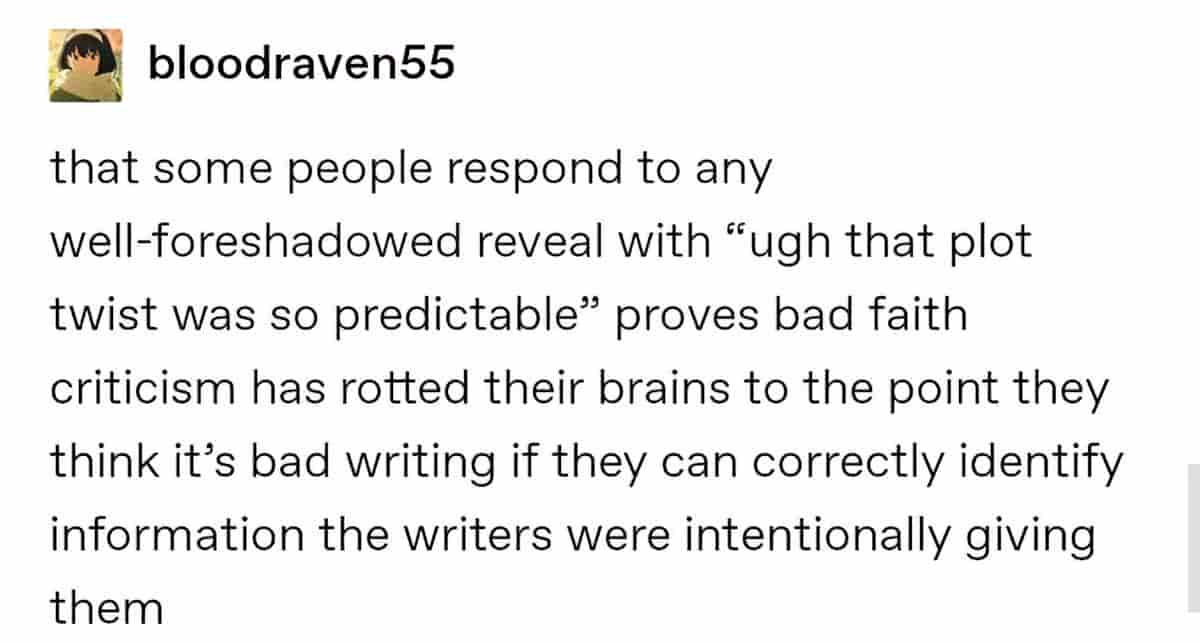

Done poorly, foreshadowing is called telegraphing. But just because you see foreshadowing happening doesn’t mean it’s done poorly. The writer below describes a common problem in the age of consumer reviews:

Adding to that: Stories look predictable in hindsight. I suspect many readers with this complaint did not, in fact, see everything coming until after they’d finished the story and then looked back with analytical reflection. Also, many people keep reading the same genre over and over, in which case you will see foreshadowing as it happens in real time. That’s how learning works.

THE SET-UP IN “THE LOADED DOG”

If you’ve been exposed to plenty of storytelling over your lifetime: TV, yarns, tall stories, books, film etc. you would have picked that as soon as the blasting-powder was mentioned, the thing would blow up and it was going to be dangerous. This is an example of Chekhov’s Gun. We all recognise this, perhaps on a subconscious level.

If you approach stories analytically, you probably also picked the part where Henry Lawson mentions the dog, and how the dog loves to retrieve things. At this point, you have probably put two and two together: The fuse will be lit and the dog will retrieve it.

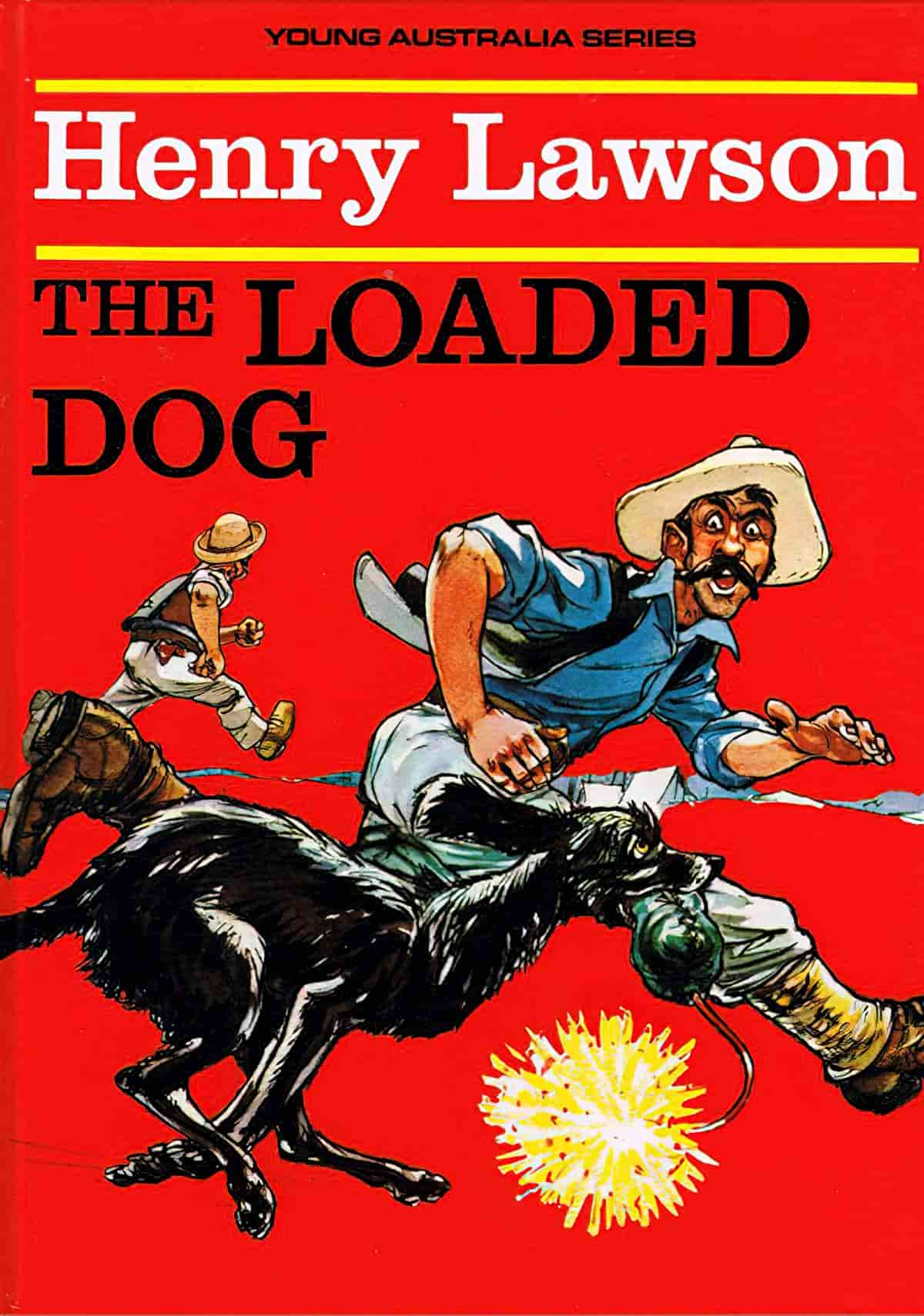

Note: We are supposed to put two-and-two together. If you don’t, the story still works. If you do, the story will satisfy. You’ll feel like a smart reader. I am very confident in saying this because a children’s version of this story was published with the following cover:

Young readers have less experience with narrative, so the cover illustration helps them out. Before starting the story, readers understand what happens with the explosive and the dog.

And that is a major difference between set-up/pay-off pairs, and foreshadowing. The set-up is very obvious. Foreshadowing a bit less so, at least until after the fact.

REFERENCES

Greaves, G A. (1961) “Blasting. Part 1. Explosives and the farmer,” Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4: Vol. 2: No. 4, Article 14.

The Henry Lawson Cheat Sheet (for the meanings of obsolete words)

Most of us know Henry Lawson and Judith Wright are icons of Australian literature. But it’s less well known that they were both disabled.

Lawson began to lose his hearing when he was nine. Wright started to lose hers in her early twenties. Neither identified as culturally Deaf, but both named deafness as a significant influence on how and why they wrote.

Henry Lawson and Judith Wright were deaf – but they’re rarely acknowledged as disabled writers. Why does that matter?