Have you ever run away from home? I tried at the age of two — so family legend has it. I escaped the house and ran, fast as my chubby legs would carry me, to the main road. I wore nothing but a nappy and bib. (The streaking part is always emphasised in retellings as if this is especially egregious.) When my parents found me they demanded to know where I was headed. So I told them like it was obvious. I was off to see the lions.

After reading Carter’s short story “Lizzie’s Tiger” I’m glad I never made it to the circus. Things might’ve turned out very differently for my parents if I had. Instead, my father built a massive gate between house and road — inaccessible from both sides to a small person. This gate terrified me in a way lions didn’t. A few years later, when I started school, I made it my morning mantra to ask for the gate to be open in time for my return. (Five year olds used to walk our own selves home back then.) I was terrified my mother would forget, in which case I’d be locked out forever. Obviously. My mother was actually pretty good at remembering to open the gate. She forgot just the once. I screamed and screamed and the entire neighbourhood thought naturally of blue murder. Eileen Austing from across the road came to my rescue. I could not be consoled. I even wet my pants.

But lions though? I had no problem with them. Lions and tigers are the stuff of fairytales — to a child they may not even be real.

Angela Carter’s fictional characterisation of a young Lizzie Borden felt the same about tigers as I did of lions. Carter’s short story “Lizzie’s Tiger” reads almost like a child’s fairytale — until it suddenly doesn’t:

- The main characters are two little girls who we meet at the ages of 13 and 4.

- They’re freshly orphaned, like many fairytale children.

- The youngest has a childlike desire — to see the circus for herself.

- The adult in her life — the father — refuses to help her, so like any good child character, she sets out on her own, into the world — her own mythic journey.

- Angela Carter’s story is almost like the inverse of The Tiger Who Came To Tea — in the picture book, a tiger comes to the house. Tiger and child indulge in a carnivalesque adventure together. In this short story for adults, a child leaves the house to find the tiger, who is not the slightest bit anthropomorphised. This is a proper tiger. Child Lizzie is at an actual carnival, but one of the adult, debauched kind.

SETTING OF LIZZIE’S TIGER

Angela Carter had the gift of turning setting into character.

That cottage on Ferry — very well, it was a slum; but the undertaker lived on unconcerned among the stiff furnishings of his defunct marriage. His bits and pieces would be admired today if they turned up freshly beeswaxed in an antique story, but in those days they were plain old-fashioned, and time would only make them more so in that dreary interior, the tiny house he never mended, eroding clapboard and diseased paint, mildew on the dark wallpaper with a brown pattern like brains, the ominous crimson border round the top of the walls, the sisters sleeping in one room in one thrifty bed.

On Ferry, in the worst part of town, among the dark-skinned Portuguese fresh off the boat with their earrings, flashing teeth and incomprehensible speech, come over the ocean to work the mills whose newly erected chimneys closed in every perspective; every year more chimneys, more smoke, more newcomers, and the peremptory shriek of the whistle that summoned to labour as bells had once summoned to prayer.

“Lizzie’s Tiger” by Angela Carter

Note various other techniques.

- First point — a lot of writers advise against using adjectives. But count the adjectives and tell me Carter didn’t deserve to use every single last one.

- Imagine a camera. Carter starts off with a long shot of the cottage, slowly zooming in from large furniture right down to mildew. Then back out to include the inhabitants of the bed — including our heroine. Why did Carter zoom in on the very small? Because Lizzie herself is very small.

- ‘Pattern like brains’ and ‘diseased paint’ not only carry the negative connotations of axe murder, foreshadowing an event which is not included in this particular snapshot of Lizzie’s life, but also personify the building itself in classic gothic fashion. In Gothic literature, houses are alive. They will swallow you up, absorb you into the walls, and provide shelter to beasts.

- In the following paragraph Angela takes the camera high above in an establishing shot — usually, in film, we get the establishing shot first. But in writing the camera is far more fluid. A fictional camera is like an electron, jumping from place to place. This foreshadows Lizzie’s journey from the shelter of her own home — her own bed — into this wider world containing people reminiscent of pirates. Why the focus on the chimneys? Because this is a view from above. Again, with focus on the miniature — a small town containing an even smaller girl, who will do big things.

- Again we have the personification of the town in the ‘shriek of the whistle’. This phrase is idiomatic so it’s easy to gloss over, but it’s typically people who shriek — not whistles.

- In the final sentence of this description of setting, Carter reminds us of the fairytale, timelessness of this event. This may be about a particular event in a particular year, but by reminding us that this is a town which has recently transitioned from an early modern town ruled by the church into an industrialised centre of manufacturing. This is the story of a girl in flux; it’s also the story of a town in flux. The most interesting stories happen in times of big change. This is a story set in the stages between 2 and 3.

FOUR STAGES of civilisation

- The Wilderness (e.g. the forest of fairytale, caves, deserts)

- The Small Town or Hamlet (civilisation on the edge of wilderness)

- The City

- The Oppressive City (which includes suburbs, which often looks like utopia until the ‘snail under the leaf‘ is revealed.)

Why is this connection important to the story? Because Lizzie herself is in transition. This is presumably her first foray out into the world, from the ‘village’ of the home into the ‘city’ of the circus, which collects a wide variety of characters and shoves them together.

The snapshot continues:

The hovel on Ferry Road stood , or rather leaned, at a bibulous angle on a narrow street cut across at an oblique angle by another narrow street, all the old wooden homes like an upset cookie jar of broken gingerbread houses lurching this way and that way, and the shutters hanging off their hinges, and windows stuffed with old newspapers, and the snagged picket fence and raised voices in unknown tongues and howling of dogs who, since puppyhood, had known of the world only the circumference of their chain. Outside the parlour were nothing but rows of counterfeit houses that sometimes used to scream.

“Lizzie’s Tiger” by Angela Carter

- When writing from a child’s point of view it’s essential to describe the world as a child would see it. Hence the gingerbread, straight out of a fairytale. Later, we’re told ‘a hand came in the night’ to hang up posters advertising the circus. This too is very fairytale-esque — to young Lizzie there is no person attached to actions. She hasn’t learnt to humanise people, and evidence may point to her never learning this skill. Moreover, this depicts Lizzie’s view of the world as full of bugaboos. The phrasing also suggests she’s drawn to these bugaboos rather than driven back into the house.

- I had to look up bibulous: ‘excessively fond of drinking alcohol’. This is a form of pathetic fallacy. The people inside the houses drink. Not the houses themselves: human attribute transferred to nearby object. Carter makes use of this same technique when she tells us the houses scream. This works because to a small child, it would seem the houses scream. A small child may not think any further.

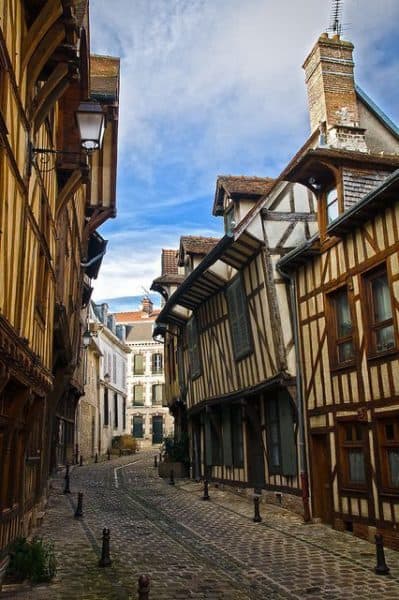

- The lean-to houses remind me of an illustrated picture book of The Pied Piper which sits on our shelf. It also reminds me of Tim Burton’s sensibility, but most of all, this is how buildings really were built in the medieval era. Before modern building standards, houses really did lean into each other. The roads between them were narrow, and they often held each other up. They collapsed. This would have felt very precarious, but maybe not to them. As for me, if I could time travel for a day back to the medieval era, I’d be very wary of setting foot inside the buildings!

The buildings of medieval Troyes have been restored to meet modern standards, but I’ve seen old photos in books which show us genuinely medieval buildings leaning into each other. A contemporary snapshot offers a little insight into the leaning nature of medieval streets. Even now, this street seems to lean into itself.

SYMBOL WEB OF LIZZIE’S TIGER

Of all the stories I’ve studied, I’m reminded most of Katherine Mansfield’s The Garden Party.

- Both are about a young female character who leaves her home on a mission

- To end up in a foreign part of town

- Coming face-to-face with death.

The similarities might come partly from the details I read about Fall River. At the time of the murders, Fall River was starkly divided into the rich people who live on ‘The Hill’ and the (largely) mill workers who lived down below in a much more culturally diverse mix. This rich/poor divide doesn’t come to the fore — dig down another layer yet — this is about the powerful versus the powerless. Lizzie is powerless because of her size, but her temperament will later compensate. We are told she is not a fearful child.

STORY STRUCTURE OF LIZZIE’S TIGER

“Lizzie’s Tiger” is a classic mythic structure and I’ve written so often on that I feel I know the main (masculine) variety inside out and back to front. This time I’ll zoom in on the most unusual points.

Like all heroes embarking on a big journey (big mostly because Lizzie’s so small), Lizzie meets a variety of characters — some help her but end up contributing to her downfall. (The group of street kids.) Another sexually abuses her. (The lion tamer.) Another man, this time benevolent, helps Lizzie to achieve her goal of seeing the tiger.

The interesting structural aspect of this story is the anagnorisis phase. On the one hand, Carter is really clear that some kind of anagnorisis has happened:

Lizzie’s stunned little face was now mottled all over with a curious reddish-purple, with the heat of the tent, with passion, with the sudden access of enlightenment.

“Lizzie’s Tiger” by Angela Carter

But none of this makes complete sense until the final sentence, when we get a big revelation. (Big revelations are known as ‘reversals’ — we’re encouraged now to see the entire story differently.) Perhaps you know more about the Lizzie Borden case than I did, and you picked it up much earlier. As for me, I had to look this person up online to check she was who I thought she was. Angela Carter seemed fascinated by Lizzie Borden — and I don’t know when she wrote them, but the fascination may have spanned years. Lizzie Borden was the main character in “The Fall River Axe Murders”, included in Black Venus (1985), and this one was included in American Ghosts and Old World Wonders (1993).

In a nutshell, Lizzie Borden entered pop culture as the notorious main suspect in the 1892 axe murders of her father and stepmother. This happened in the beautifully symbolically named Fall River, Massachusetts. She was acquitted, as it happens. In any case, if you know that about Lizzie Borden, you know what the character’s revelation was in this short story: Hypothetical young Lizzie has realised that she contains great power within herself. She is the tiger. In fact, you don’t need to know about Lizzie Borden to have picked that much up. It’s clear from various clues within the text that the tiger is Lizzie’s animal analogue:

- Lizzie is strangely entranced by it

- Both she and the tiger are abused by the tamer (though at this point, only the tiger has exacted any sort of revenge, in the form of scars)

- Lizzie ends up wearing a similar mottled pattern to the tiger.

STORY BEHIND THE STORY

Roald Dahl wrote a similar story about Adolf Hitler as a baby. When he reveals the identity of the baby in the story, the writer asks us to examine whether we still have sympathy for this small child. If we saw Adolf Hitler as a baby and knew what he’d turn into, would we save his little life?

Likewise, an episode of Black MIrror asks us to examine our empathy after withholding the culpability of the empathetic main character until the last few minutes of the story.

These imaginings of notorious people as children are always about empathy. Do horrible adults deserve empathy? How much? Are any of us really responsible for the things we do, or do life circumstances send us forth along a path which seems full of choices but is actually more fatalistic?

Some reviewers have complained that Angela Carter treated her characters like specimens for analysis. Lizzie’s Tiger may be a good example of that. Stories like these are inevitably about the role nurture in shaping personality, sometimes attempting to home in on the moment in which a good child turned bad. In reality, there are rarely such defined moments. We like to think there are. We like to see them in fiction.

SEE ALSO

The Tiger’s Bride by Angela Carter