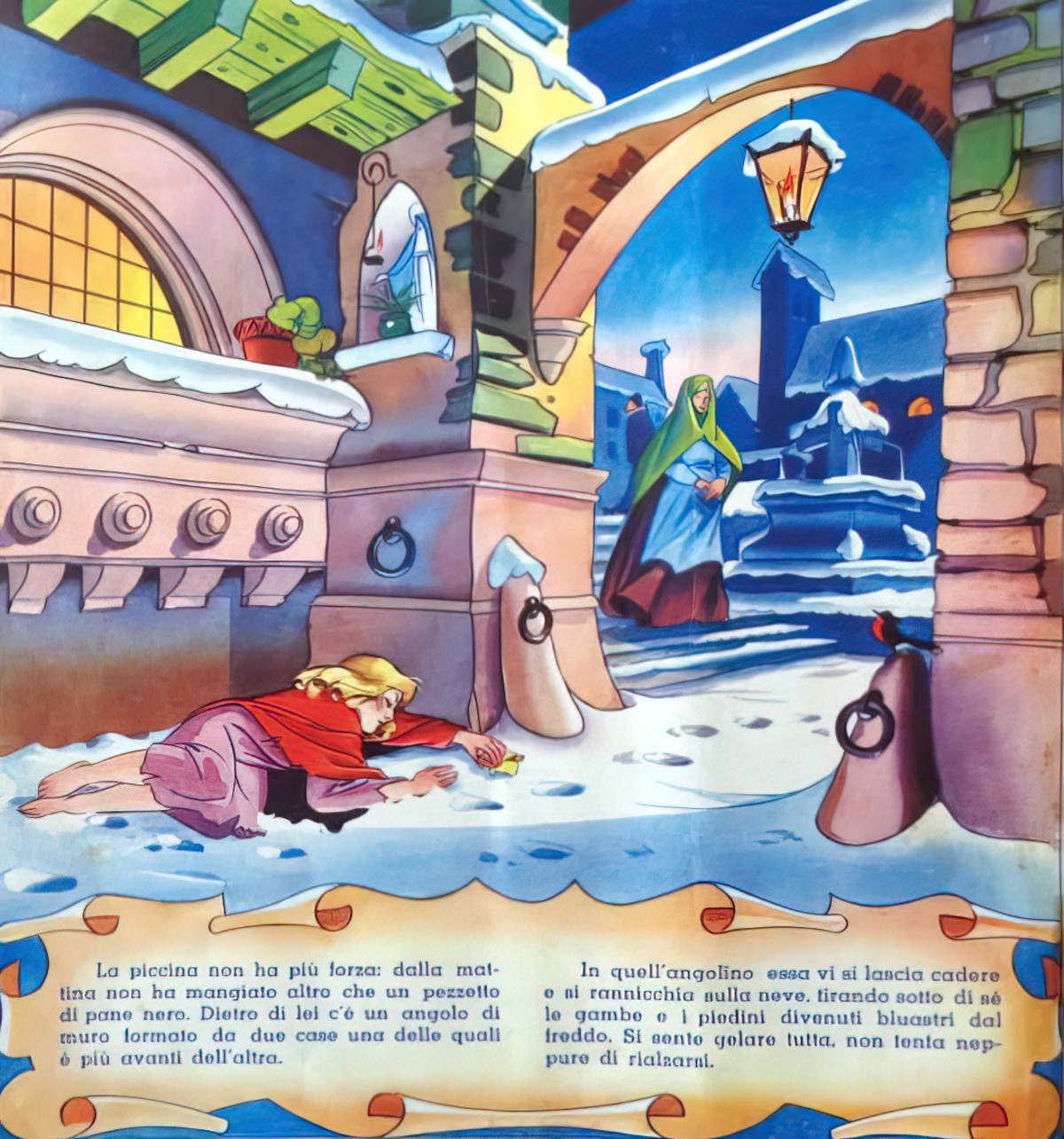

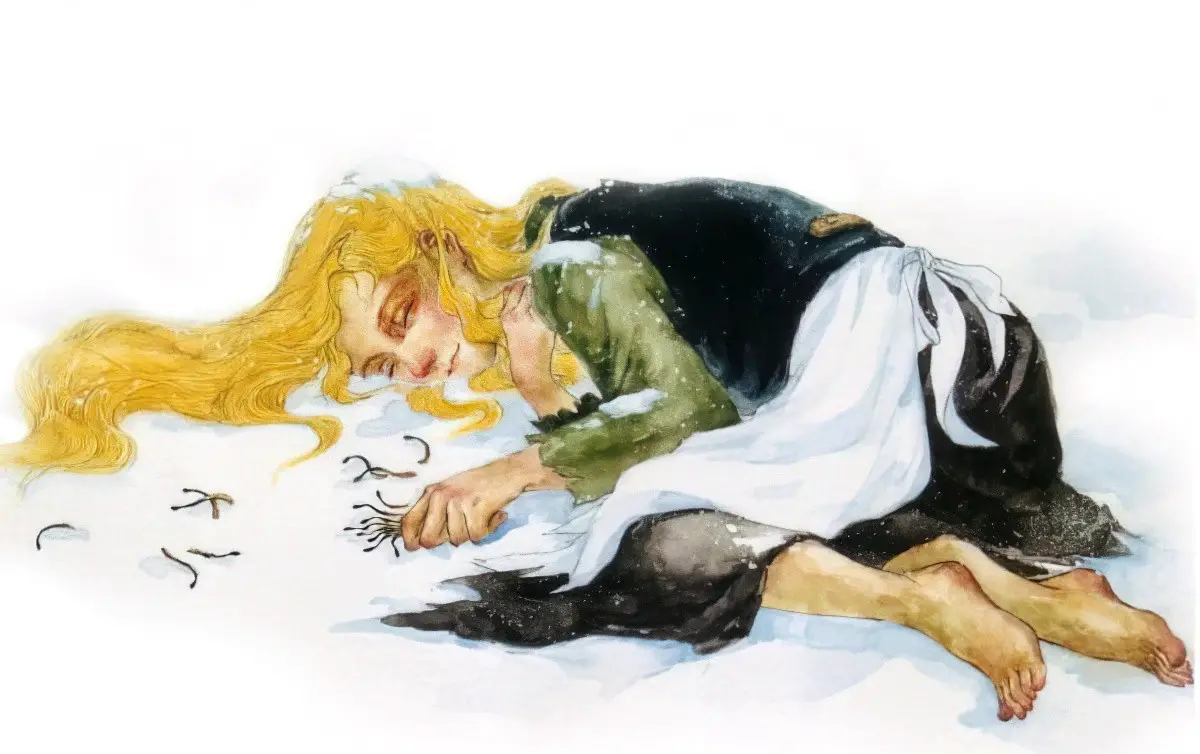

To a modern audience, The Little Match Girl is unbearably tragic. Perhaps, like me, you vividly recall reading your version of this story as a young kid and being profoundly affected. For me, it was probably the first time I considered the possibility of childhood death.

Hans Christian Andersen was commissioned to write a story based on a woodcut. This woodcut illustration was by painter Johan Thomas Lundbye and was of a poor girl selling matches, dressed in rags. It was widely recognised in Denmark at the time and appeared in calendars with a caption encouraging people to give to the poor. Lundbye himself died at the age of 29, during the Three Years War in Denmark but it’s not clear whether he was accidentally shot or whether he took his own life.

If you’d like to hear “The Little Match Girl” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Little Match Girl” was published January 2021.

Here it also at Librivox.

SETTING OF THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL

For the Victorians, child death was all around. These days when a young life ends we focus on all the years lost. But the Victorian mindset was a little different. Sad as death inevitably still was, the focus was not on the years wasted but on the opportunities presented when one is able to fly up to heaven with their childhood innocence intact.

Alison Lurie writes not of The Little Match Girl but of Peter Pan when she talks about the Victorian ideology of childhood innocence, but it applies equally to the mindset of Hans Christian Andersen:

In every society, every century, some time of life seems to embody current cultural ideals and have superior prestige. In ancient China, we are told, the greatest honor was given to old age; America in the 1960s admired teenagers, attributing to them boundless energy, political altruism, and a polymorphously joyous sensuality.

The Victorians, on the other hand, preferred children who had not yet reached puberty. The natural innocents of Blake and Wordsworth reappeared in middlebrow versions in hundreds of nineteenth-century stories and poems, always uncannily good and sensitive, with an angelic beauty and charm that often move the angels to carry them off. But the early death of these children was not felt as wholly tragic, for if they never became adults they would escape worldly sin and suffering; they would remain forever pure and happy.

Don’t Tell The Grownups: The Subversive Power of Children’s Literature

How do we really know this is set in Victorian times, though? That is the assumption, because Hans Christian Andersen lived during this time, and the sensibilities line up. But this is a more timeless story than that, and others adapting this tale have chosen a variety of different eras and places for the story. Another common era for setting this story is the early 20th century, sometimes in an American city, sometimes in London.

SEASONALITY IN THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL

There is something both comforting and dangerous about a village blanketed in snow. Snow can spell death for a human on the wrong side of a window, but for home dwellers tucked up safely in their living rooms sipping mulled wine, snow really does feel like an extra ‘blanket’. I wonder if this comes from the reality that hunting creatures also hunker down in the snow. Bears, for instance, hibernate, so you’re less likely to get mauled by one of them. Despite the almost mythological fear of being mauled by large, wild animals, the biggest danger to humankind has always been other humans. It feels likely that a town is less likely to be assailed by a gang of marauders in the heavy snow.

Andersen used the time span of the year as a metaphor for the time span of a life — the story takes place on New Year’s Eve, which neatly coincides with the very end of the girl’s life.

For more on this see The Seasons Of Storytelling.

SOCIAL INEQUALITY

The Little Match Girl is not set in any specific place, but throughout Europe this was an era of industrialisation, before laws existed to prevent the complete slavery of peasants and the breakdown of family. Children from poor families commonly worked very long days, seven days a week. It was illegal to beg on the streets, so children would ostensibly try to sell a product, hoping for donations. This explains why the girl has a fistful of matches but nothing else — the matches are simply props for her begging. As a kid I always wondered what she planned on doing after the fistful of matches had gone. Even if she had sold them, wasn’t death her eventual fate?

FOOD

In The Little Match Girl the smell of roast goose emanates onto the street. This is a traditional Danish Christmas dish.

The traditional Danish Christmas meal is

- roast pork, duck and goose

- boiled potatoes

- red cabbage

- gravy

For dessert, the classic dish is ris à l’amande;— cold rice pudding with whipped cream, vanilla, almonds and hot cherry sauce. Also ‘risengrød’ — hot rice pudding.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL

SHORTCOMING

In fairy tale world, if a name starts with ‘Little’, watch out. It means they’re not going to make it to adulthood.

The father in this tale is very much in the background — a villain/monster who threatens to beat her if she comes home without having sold the matches. He’s not going to come out looking for her when he realises she hasn’t come home. The Little Match Girl is — emotionally, and for story purposes — an orphan. In Victorian Denmark there is no safety net for abused and starving kids, so unless she can sell matches she has no money to find food or shelter. Memorably, she is without shoes. Hans Christian Andersen’s father had been a shoemaker, so Hans paid special attention to footwear. He had also been bullied by other children as a child, so he has a boy run off with one of the girl’s slippers after it slips off.

DESIRE

She just wants love, shelter and food — the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid (misappropriated from Native Americans, among other problems).

OPPONENT

The setting itself, in which she is invisible to passersby and helpless against the climate.

Although this story has been rewritten many times, often with the ending changed so that the Little Match Girl ends up safe and happy ever after in a warm house, this story was a critique on economic inequalities. The story was written at a time when Denmark was doing pretty well, despite some social unrest. Yet there were still abandoned children walking around the streets, as there always are in times of general prosperity. The opponents of this story are people who turn a blind eye. When the ending is changed there is no longer any human opponent — just the cold outside.

PLAN

She has a few matches in her possession. This is all she has left. She will sell the matches for money.

But she gives up trying to sell matches after the townspeople disappear into their own warm homes. She uses the matches to give herself a little warmth.

BIG STRUGGLE

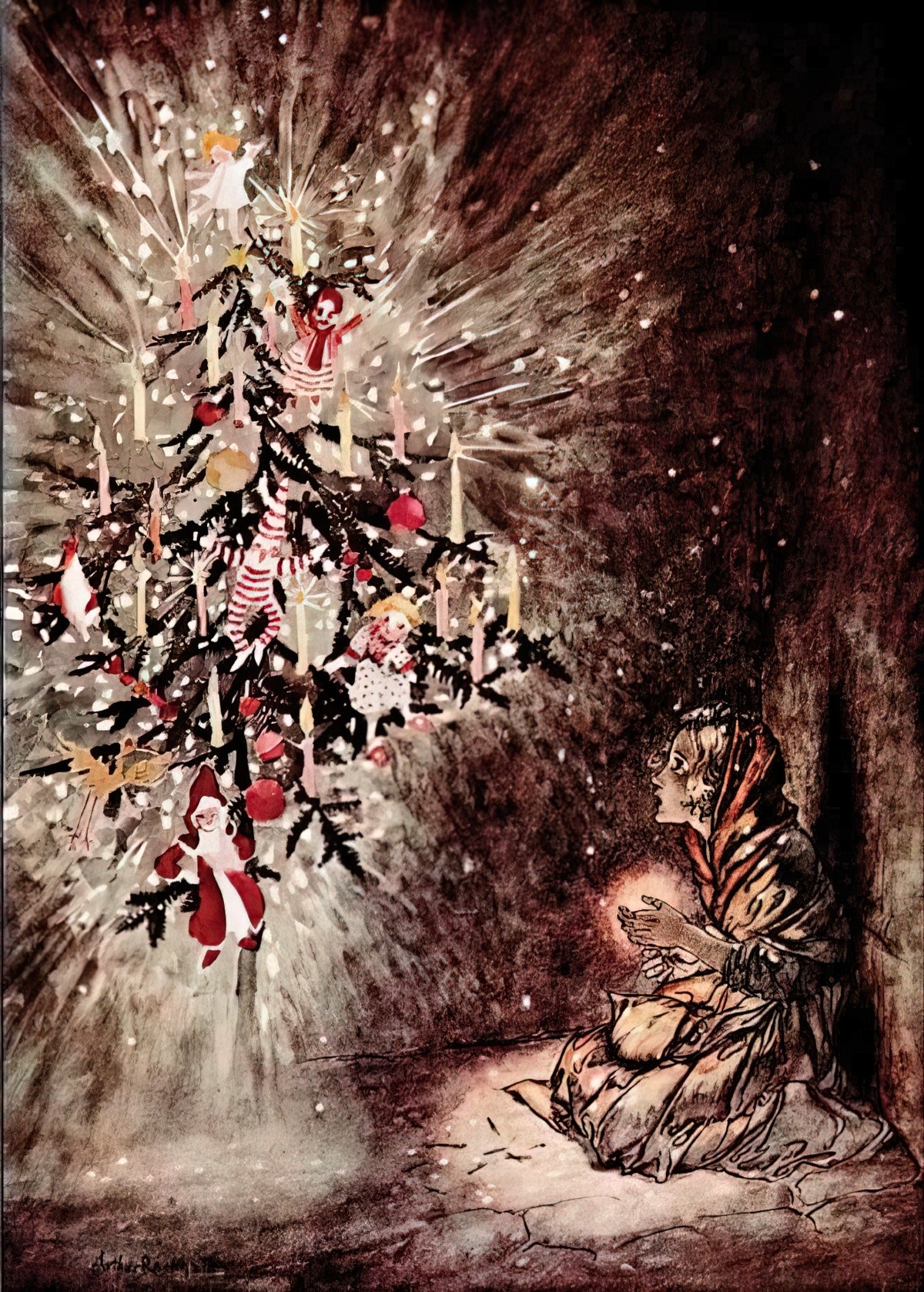

As she slips into a hypothermic slump she imagines the measly warmth of the matches have brought her all the things she needs.

These matches are a simple, everyday item which Hans Christian Andersen manages to imbue with longing. He does this in other tales too, for example with the pea in The Princess and the Pea.

ANAGNORISIS

When the girl’s grandmother appears the reader realises she is meeting her in heaven. For modern audiences this is tragic; for Victorian audiences this was the best thing that could happen to her.

In the end The Little Match Girl flies to Heaven. For more on that see The Symbolism Of Flight In Children’s Literature.

NEW SITUATION

The Little Match Girl will live happily in heaven with the grandmother she loves. Hans Christian Andersen was really close to his own grandmother. His grandmothers and older women all have fairy godmother, semi-magical powers attached to them. Here she is surrounded by an aura of light.

Hans Christian Andersen was a devout (possibly Orthodox) Lutheran. Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestant Christianity. Lutherans split from Catholics in the early 1500s. A main difference between Lutheranism and Catholicism: Lutherans believe that scripture is the final authority on all matters. For Catholics, authority comes from both the scriptures and the tradition.

According to Lutheran thinking God persists after death. People are judged before being admitted to Heaven, but worrying about this judgement (or about the future in general) is not considered a mark of faith. A good Lutheran goes about their daily life in accordance with the rules of the church/God without worrying too much about the future.

There seem to be two main interpretations of this ending:

- Children are full of imagination and are capable of enduring severe hardship with a positive attitude

The Little Match Girl is a bad example of a human being because she just gives up on life.

Death as a divine release

Death, of course, is not always looked upon as punishment. In fact, in many religious stories virtuous people (often children) are “called home,” frequently under miraculous circumstances. For these blessed individuals, death is a divine release from the sorrows of this world.

Once there was a poor woman who had two children. The youngest one had to go into the forest every day to find wood. Once a little child helped him gather the wood, carried it to the house, and then disappeared. The child told his mother about the helper, but she didn’t believe him. One day the helper child brought a rose and told the child that when the rose was in full blossom he would come again. The mother put the rose into some water. One morning the child did not get up; the mother went to his bed and found him lying there dead. On that same morning the rose came into full blossom.

Source: Retold from The Rose (Grimm, Children’s Legends, no. 3). For similar accounts of foretold deaths, see Grimm, German Legends, nos. 263-267.

Religious legends are told throughout the world, and those describing premonitions and forewarnings of impending death are particularly widespread and persistent. Such accounts spontaneously emerge at solemn family gatherings, then disappear when the mood brightens. They surface again when needed — unrehearsed at other sober occasions, or sophisticatedly refined in universal myths and in the great tragedies of world literature. At their primeval level, these accounts describe only modest miracles: the opening of a flower, the appearance of a bird, the dream of a departed loved one, or perhaps nothing more portentous than an uncanny feeling. They do not claim the power to change the course of human destiny, nor do they offer explanations to life’s unfathomed mysteries. Instead, they are expressions of faith in continuity and of hope for justice, even at times when it is painfully evident that, on this earth at least, we do not live happily ever after.

Pitt.edu

SEE ALSO

Hans Christian Andersen wrote this story using a painting as inspiration. How would you write a fractured fairytale using The Little Match Girl as inspiration? Gregory McGuire did it for an NPR Christmas special some years ago. The story is called Matchless. He took a minor character and made made him more sympathetic.

Header illustration: Anne Anderson, Scottish illustrator.