“The Little Governess” (1915) is one of the most functionally useful stories Katherine Mansfield wrote. It’s a cautionary tale without the Perrault didacticism. It’s Little Red Riding Hood, but social realism. This story exists to say, “You’re not alone.” It’s a gendered story, about the specifically femme experience of being alone in public space. Some critics find the ending inadequate. This is a stellar example of a lyrical short story with emotional closure but no plot closure. And it only succeeds in offering emotional closure if the reader can identify with the experience.

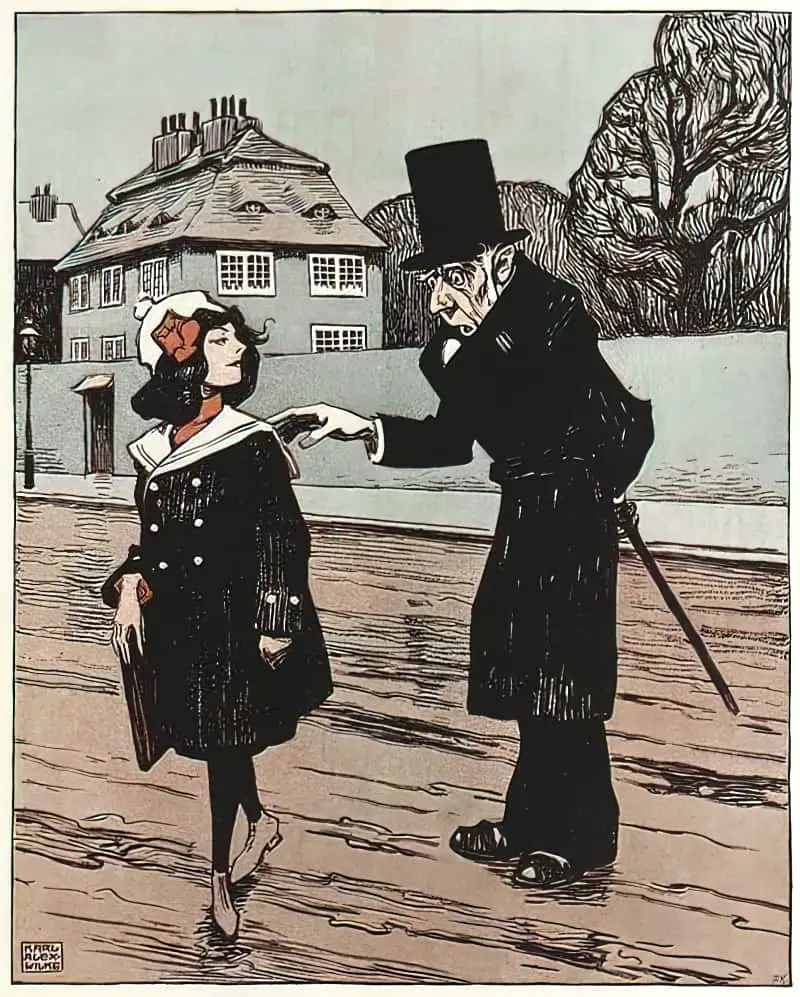

Tricksters, villains and criminals are everywhere in narrative. But throughout storytelling, across history the femme seule must deal with a particular subcategory of predator: The sexually predatory trickster. “The Little Governess” is Mansfield’s treatment of that particular dynamic.

Though this story is over 100 years old, it hasn’t dated as much as we might have hoped. Have you ever got a bad feeling about somebody but didn’t want to seem rude, so went along with their plan anyway? “The Little Governess” is a case study into why a young woman might ignore her instincts and find herself isolated.

A woman could offer no greater cooperation to her soon-to-be attacker than to spend her time telling herself, “But he seems like such a nice man.” Yet this is exactly what many people do. A woman is waiting for an elevator, and when the doors open she sees a man inside who causes her apprehension. Since she is not usually afraid, it may be the late hour, his size, the way he looks at her, the rate of attacks in the neighborhood, an article she read a year ago—it doesn’t matter why. The point is, she gets a feeling of fear. How does she respond to nature’s strongest survival signal? She suppresses it, telling herself: “I’m not going to live like that, I’m not going to insult this guy by letting the door close in his face.” When the fear doesn’t go away, she tells herself not to be so silly, and she gets into the elevator.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

CONNECTION TO MANSFIELD’S OWN LIFE

Katherine Mansfield wrote “The Little Governess” in 1915 while in Paris. She spent that year dividing her time between John Middleton Murry’s flat in London and Francis Carco’s flat in Paris, near the Quai des Fleurs (‘Flower Quay’). Carco was away at war and she was using his apartment as a base. (Francis Carco was a bohemian writer and apparently inspired “Je ne parle pas français“.)

MANSFIELD WAS FREQUENTLY A FEMME SEULE

The French phrase ‘femme seule’ (woman alone) is repeated throughout “The Little Governess”, functioning as a motif. Mansfield also utilised this phrase frequently in her private writing around this time, along with ‘dame seule’ (with connotations of ‘spinster‘ alone, I guess).

Gerri Kimber has this to say about that:

“The Little Governess” is an uncomfortable depiction of a young girl, journeying alone through Europe, at the mercy of predatory males. The notion of the ‘dame seule’ persists till the end of Mansfield’s life on both a physical and emotional level. It must be remembered that for most of Mansfield’s time in France she was ‘une femme seule’ — reliant on writing letters for conversation which she could not obtain elsewhere; she even conducted her own personal ‘dialogue for one’ within her notebooks and diaries. On an emotional level, she would leave Murry increasingly behind, ultimately demonstrated by her decision to go to Fantainebleau and enter Gurdjieff’s community alone.

Katherine Mansfield’s French Lives, 2016, Gerri Kimber

The Loneliness Of Victims

The reason femme seule is a motif and not simply a repeated phrase: The isolation suggested by the word ‘seule’ (alone) has a multivalent function in this story which is broadly about the various types of isolation.

The little governess is physically alone, which is safe; a predator invades her alone space. But the toughest and most enduring loneliness is yet to come:

- There’s a loneliness that comes in the wake of incidents such as these, where you start to see every stranger as a potential predator.

- You learn not to trust your own decisions. And isn’t your own self your strongest ally? Normally?

- You can’t predict the many terrible outcomes of any given situation. A predictable world is a comfortable one. When you first realise this, you feel essentially alone.

- There’s also the loneliness that comes from thinking this has never happened to anyone else, because although older women warn you, they only tell you what not to do; they don’t explain how the world really is.

- Then there’s the loneliness that follows humiliation and shame. In hindsight her own actions will seem foolish to herself. She dare not share the experience.

- Besides, nothing bad really happened. In hindsight, was it really as bad as it felt? This is the type of loneliness that derives from separating your one-time lived reality from your subsequent re-interpretation of it.

YOUTH AS A PRECARIOUS STATE

Katherine Mansfield was unusual for her era, once again ahead of her time. She did not sentimentalise youth as other writers were doing at the turn of the last century. She acknowledged and depicted the vulnerabilities of inexperience. Mansfield’s single women were less safe than many of her children, who were mostly protected by the family unit.

There’s a reason why this story is called “The Little Governess” and not simply “The Governess”. The ‘little’ emphasises the main character’s youth. Young, femme coded characters who embark upon their maiden voyage out into the world are not technically children, but in common with children, they are prey. This applies more in some eras and cultures than in others, but it always applies. And it’s impossible to ascertain your own degree of vulnerability at any given point. The constant vigilance required by any vulnerable demographic is exhausting.

SETTING OF “THE LITTLE GOVERNESS”

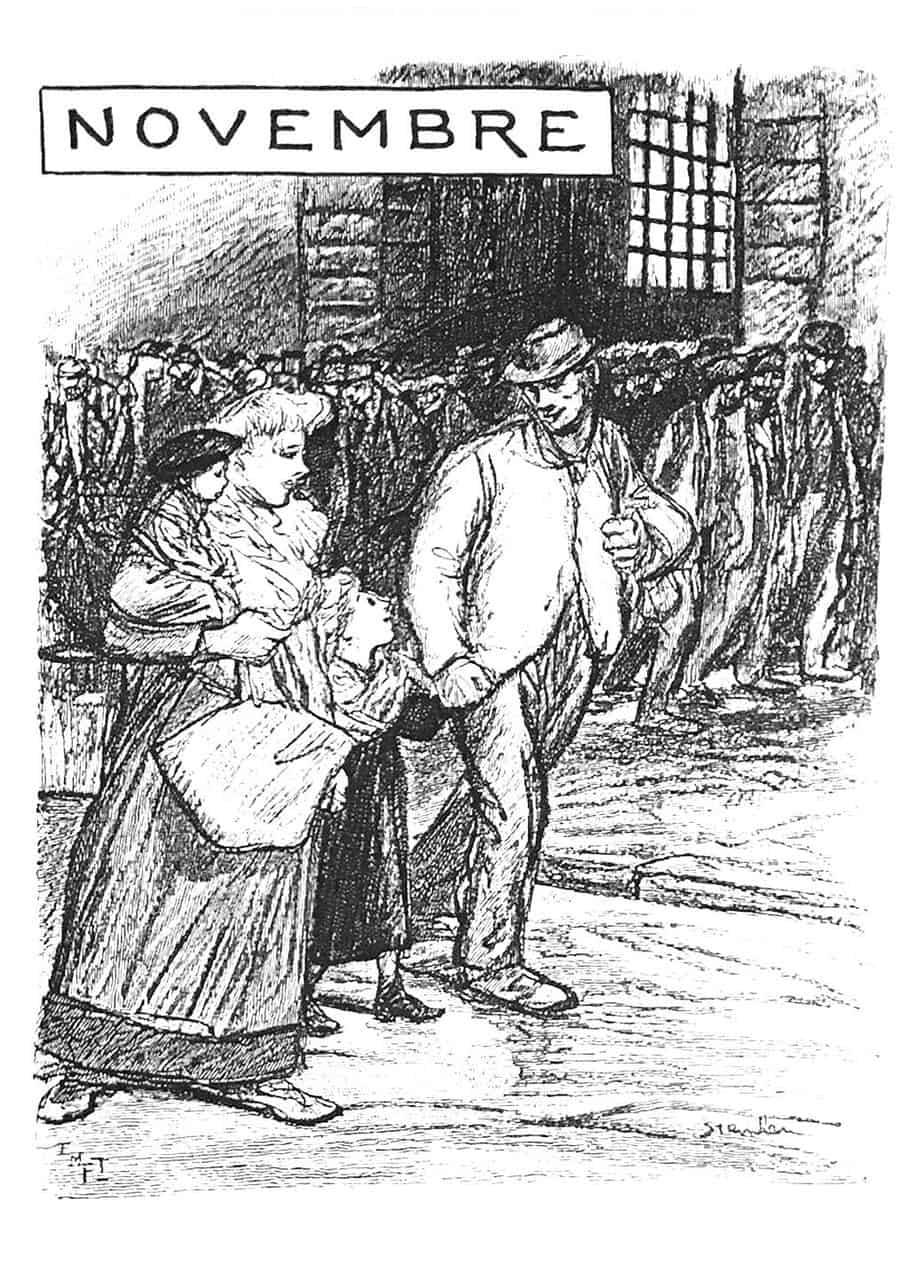

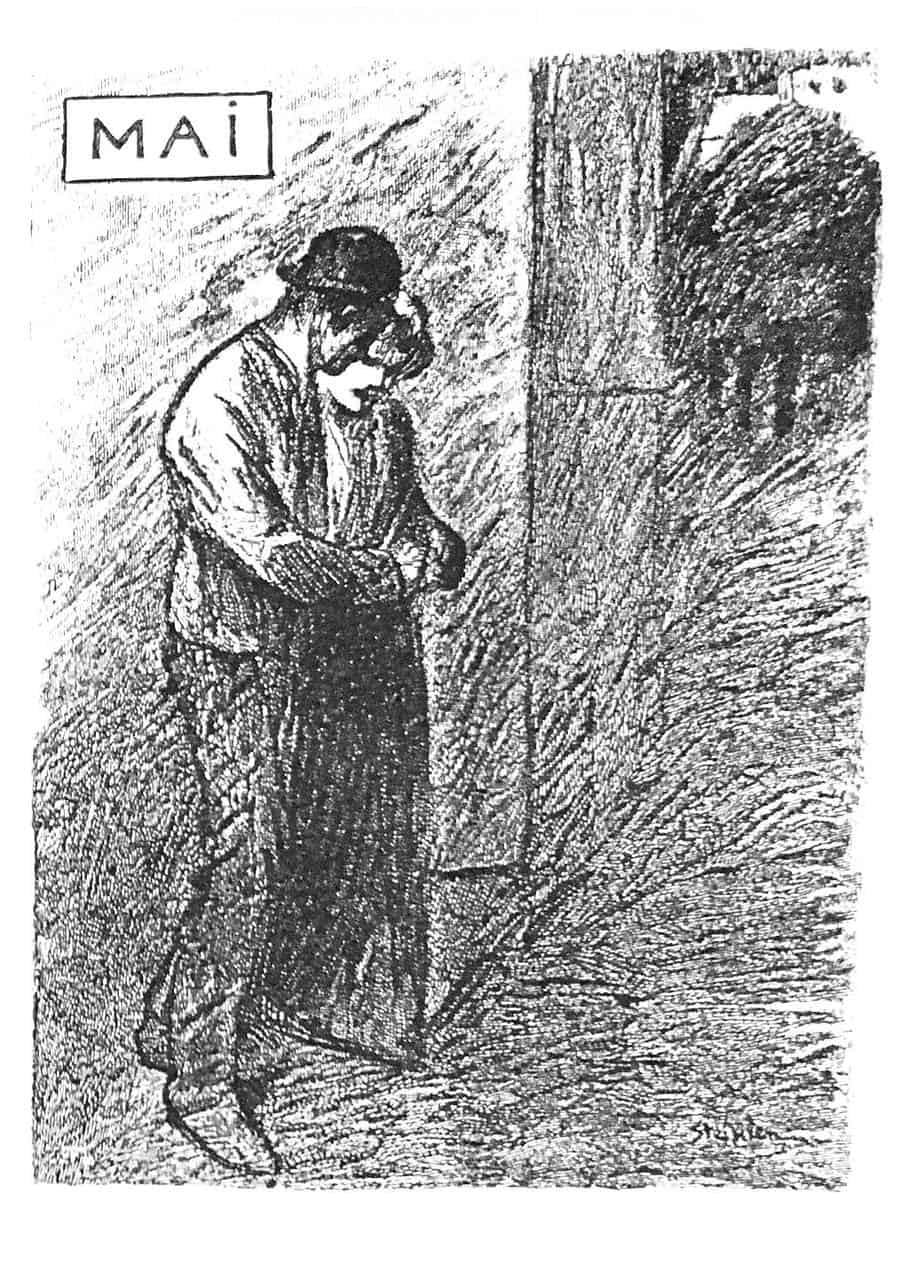

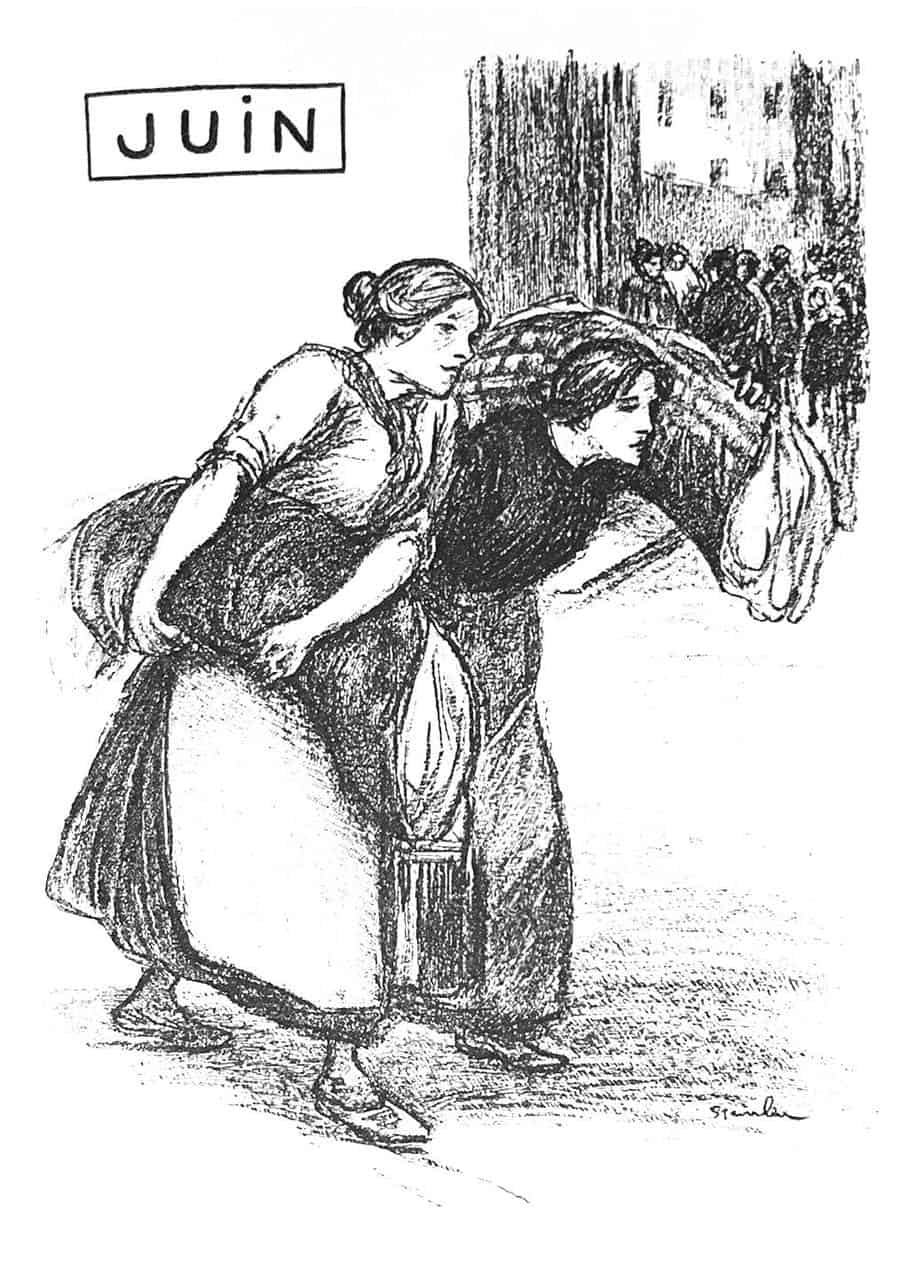

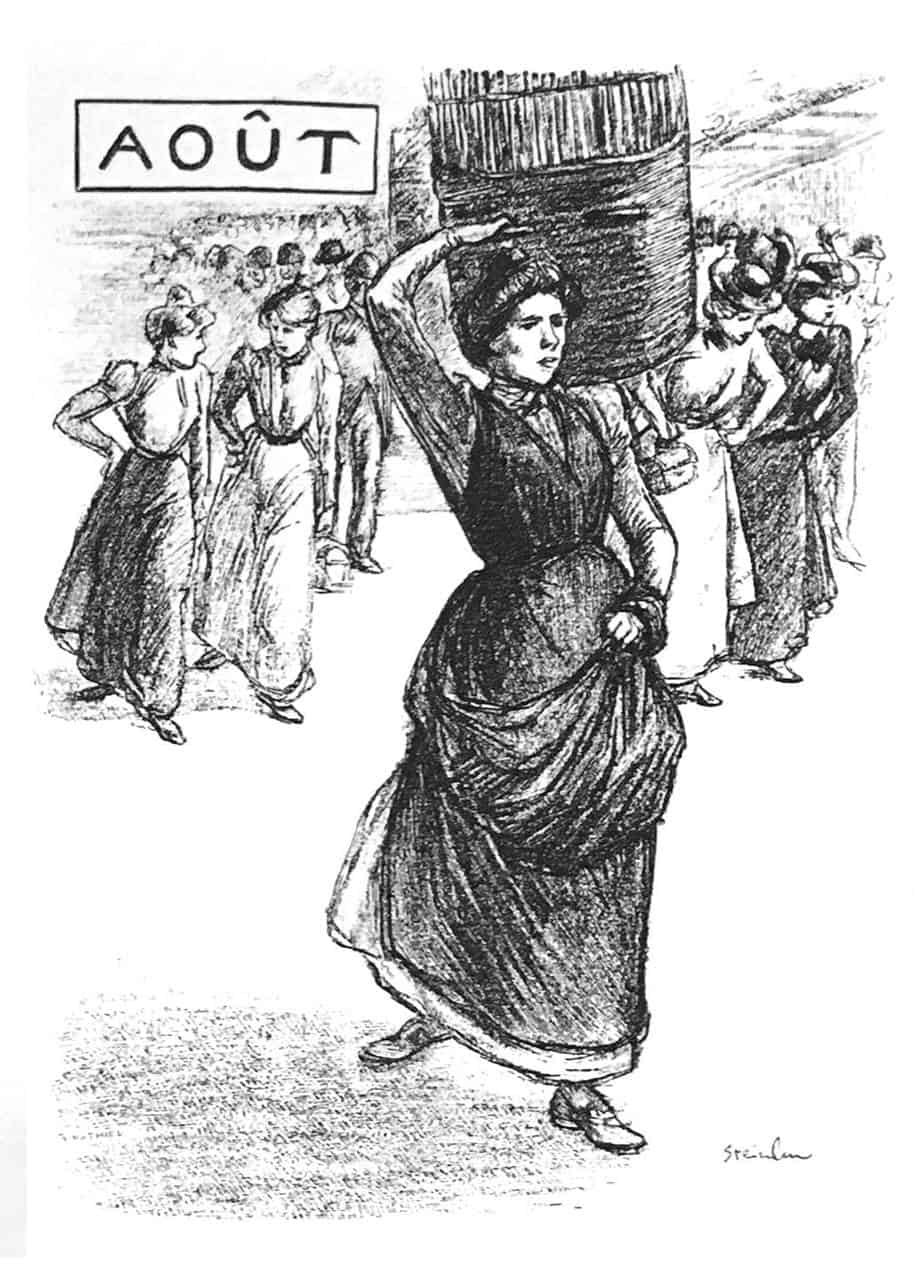

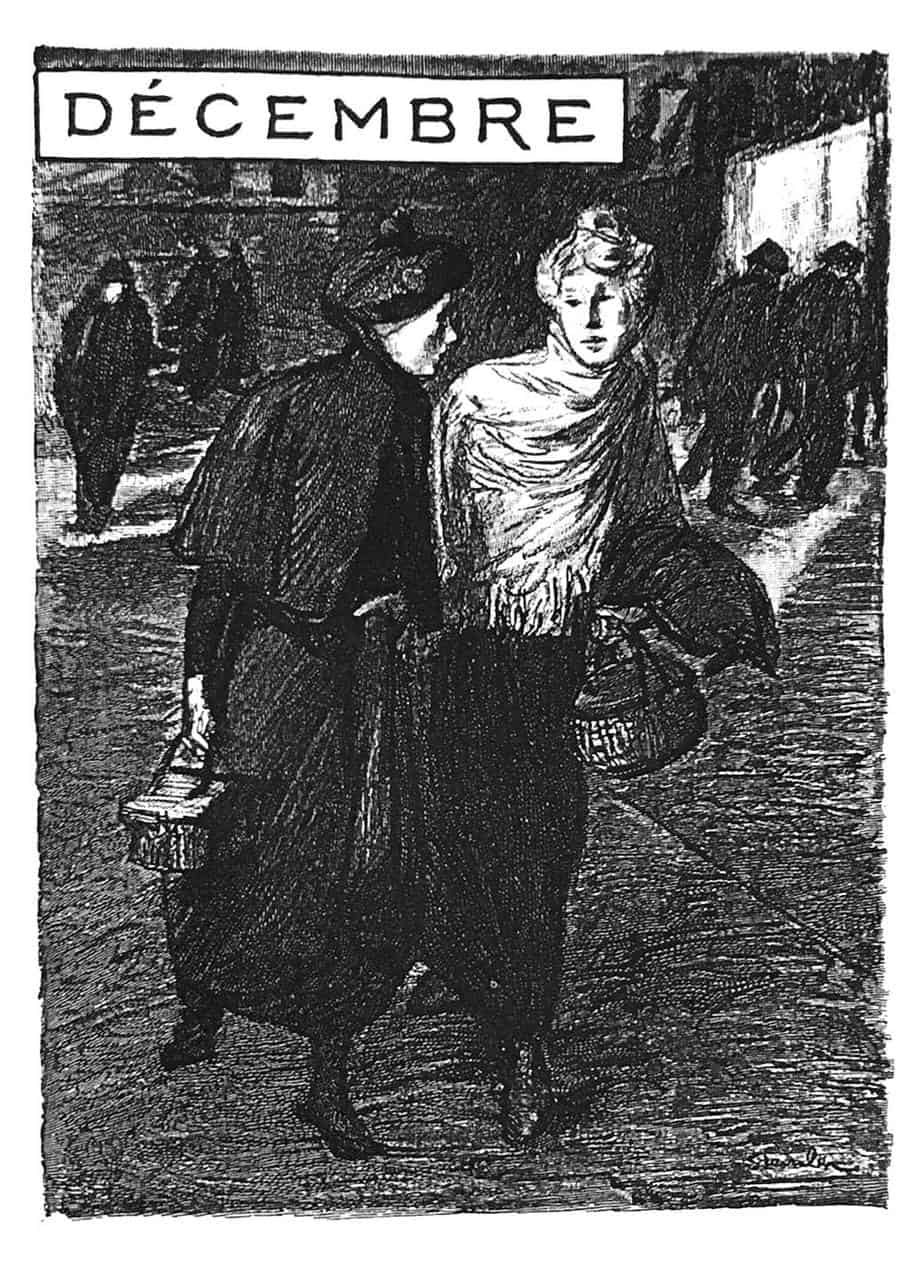

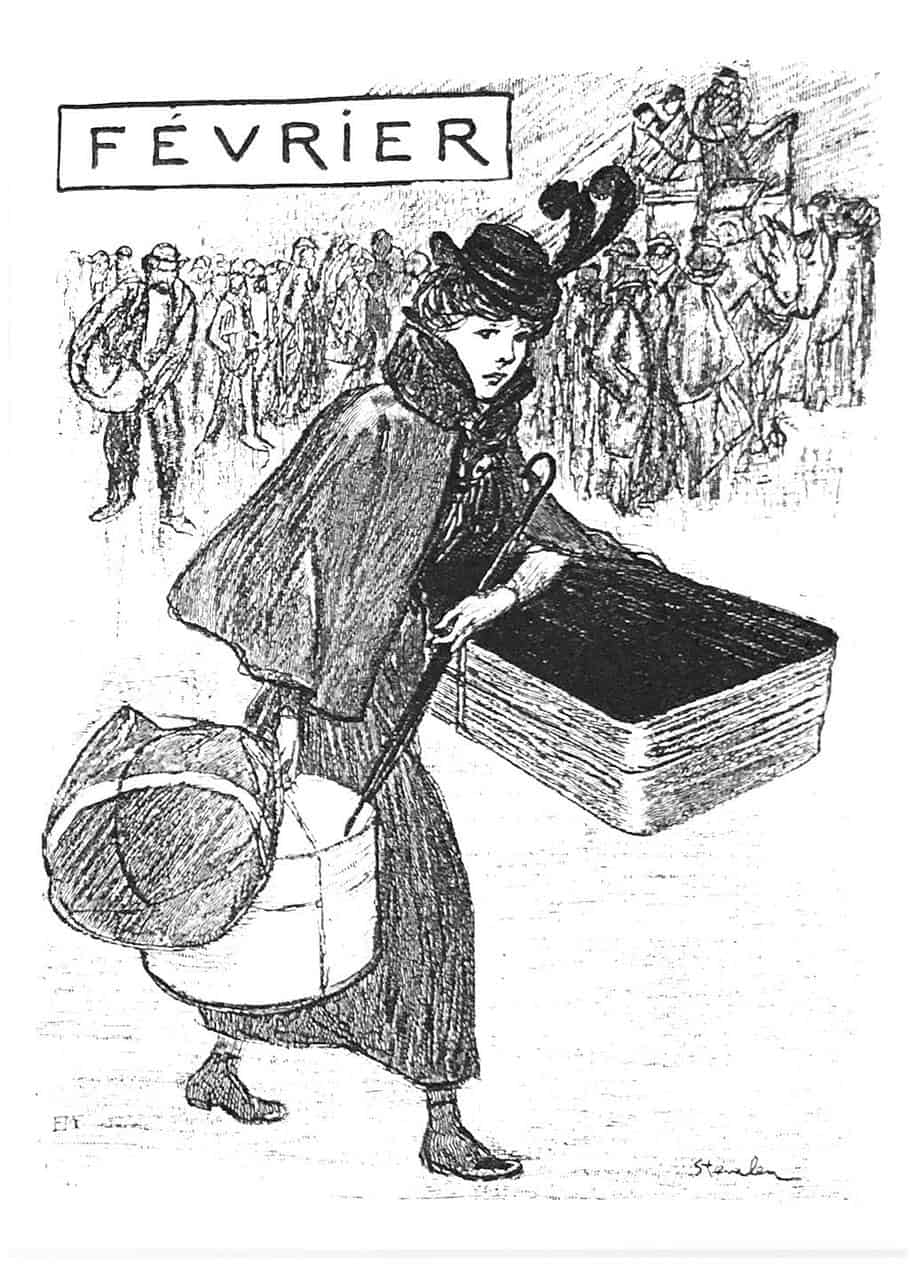

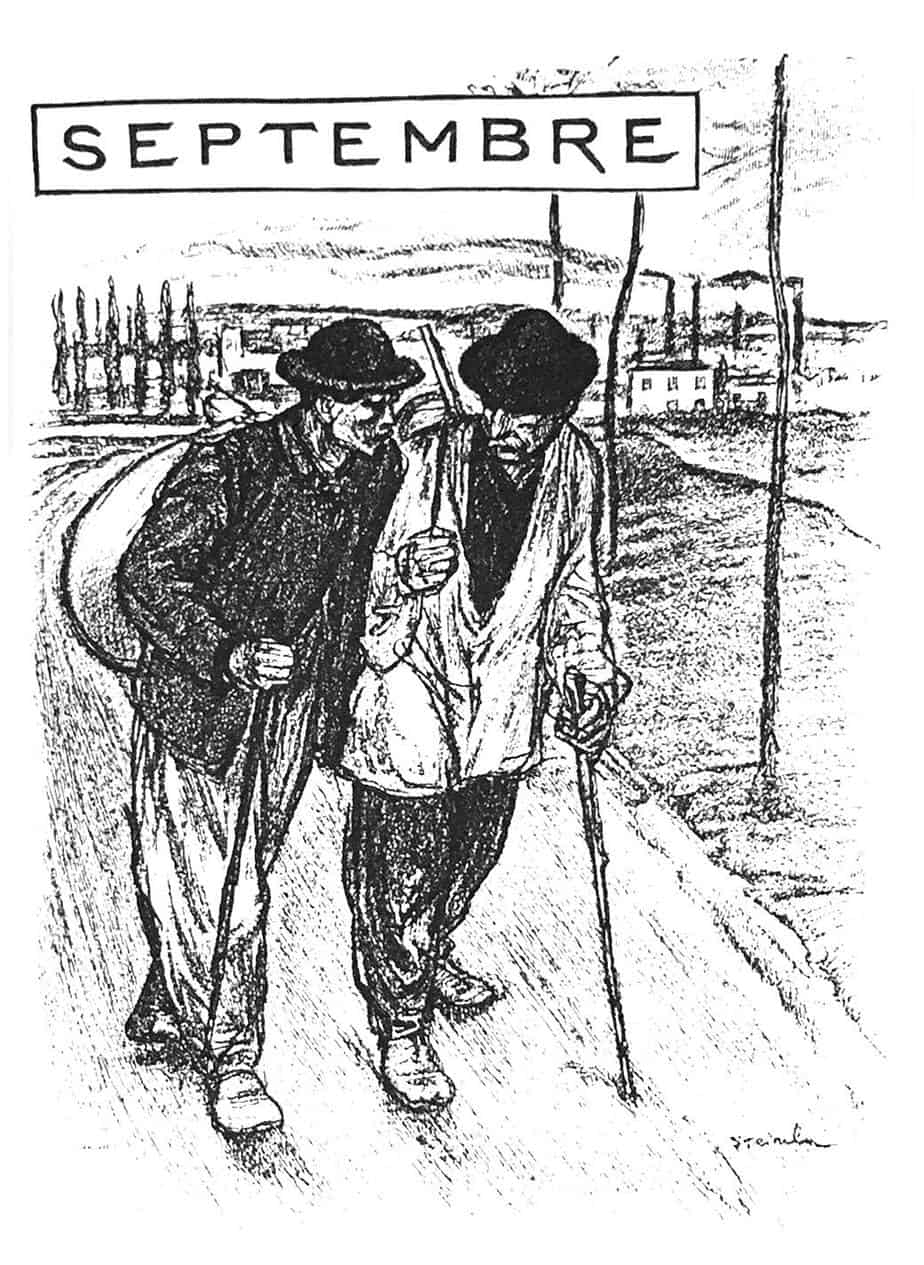

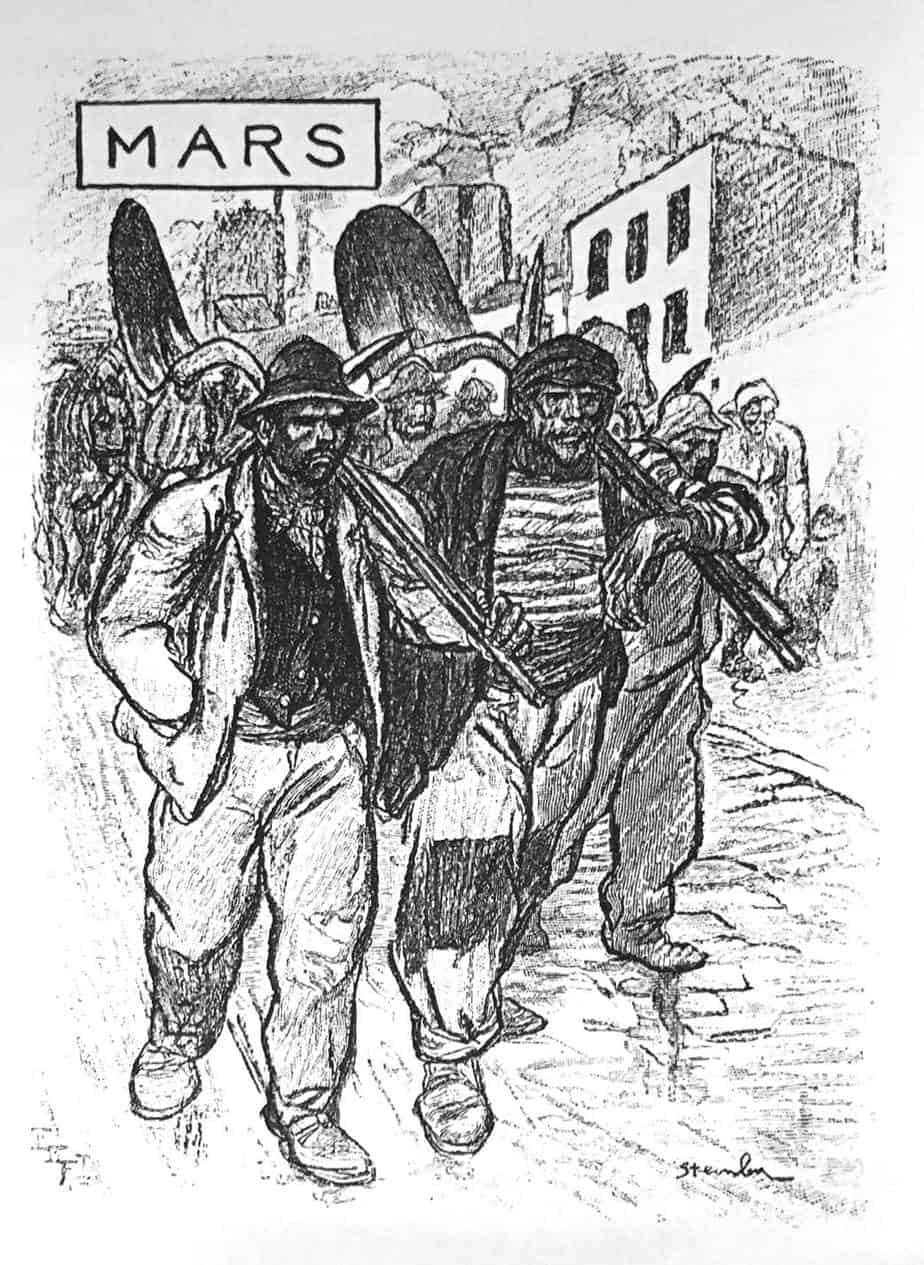

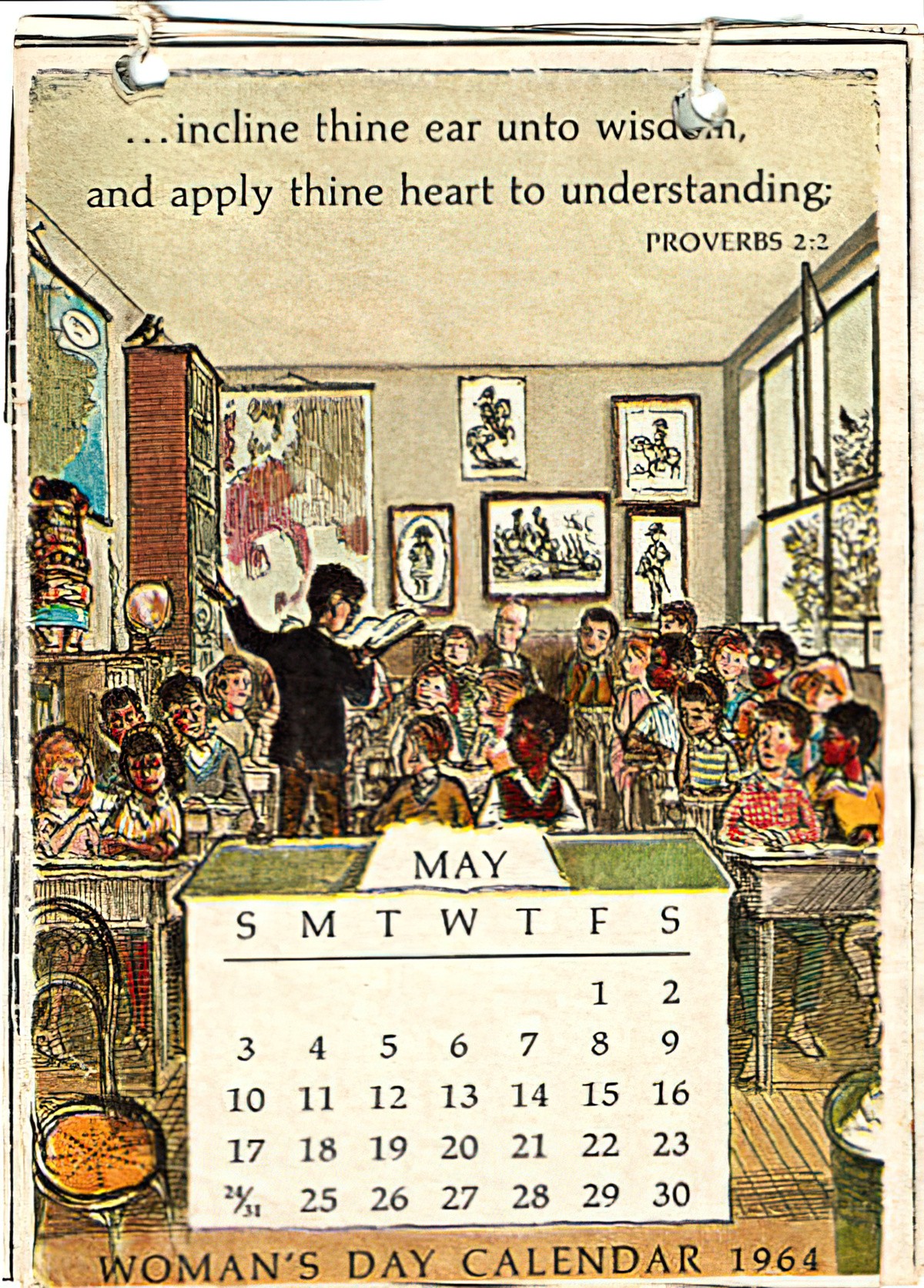

This particular journey begins in France. Below are some sketches of French life, drawn 14 years before Mansfield wrote her short story. When I saw the February sketch I thought of Mansfield’s “The Little Governess”. Might she have looked a bit like that? Eyes darting, hunched posture, clearly moving from one place to another for the long haul, clearly alone?

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE LITTLE GOVERNESS”

The hero’s journey provides a classic example of the difference between men and women embarking upon mythic stories. Men leave the home, encounter a variety of allies and foes along the road, then eventually prove themselves in battle. Men typically have weapons at their disposal.

“The Little Governess” has a hero’s journey structure; a young character sets off, encounters various characters and, as in any mythic story, she must decide whether strangers are allies or opponents.

But a woman cannot have the same kind of heroic journey as a man. (This is why there’s such a thing as female mythic structure.) Mansfield understood that a woman embarking on a typically masculine journey encountered obstacles that were qualitatively different from those typically encountered by men.

MEN AND TRICKSTER PREDATOR STORIES

To digress slightly, male encounters with sexual predators have been almost entirely invisibilised, and only recently taken up by writers such as Christos Tsiolkas in his novel Damascus, in which case we realise, of course Jesus was sexually assaulted. Of course he was.) If we’re talking about social realism, the homme seule on journeys, like the femme seule, should also encounter sexual predators. But those experiences do not line up with society’s view of male heroism, and we find this plot point disproportionately less in narrative than in life. When we do see male sexual assault in fiction, it’s so shocking it is cut when catering for mass audiences (see for example Deliverance). However, those same mass audiences are frequently shown on-the-page female sexual vulnerability. Audiences are numb to that particular dynamic.

Where fictional male characters do encounter sexual predator tricksters, those tricksters tend to be women, depicted as alluring, glamorous witches.

Though the social realist experience of male-on-male sexual predation requires more exposure, of the thoughtful kind, audiences see male-on-female sexual assault all. the. damn. time. in. everything. Too often, sexually charged violence against women is gratuitous, titillating, and the storyteller’s perspective choices show vulnerability via the perpetrator’s gaze, not the victim’s. Mansfield’s story counters that dominant narrative.

Notice how Mansfield doesn’t dwell on the violence. Maybe she was sick of romanticised, sexualised violence against women. Whatever did or didn’t happen inside the old man’s room isn’t the story here; it’s the sequence of events which leads to isolation, which leads to layered, enduring loneliness.

PARATEXT/INTERTEXT

Mansfield’s contemporary readers would have been well-versed in the Harlot’s Progress plot, which was everywhere in those days. In this narrative, a young woman is targeted, victimised then blamed for daring to set out into the world alone. In the Harlot’s Progress plot, women will be accosted by men who can’t help being men, because men can’t be expected to control their urges — all moral culpability rests upon the young woman. Will she manage to escape their clutches and lead a nice life, or will she succumb, and lead the life of a harlot?

Short stories don’t tend to come with blurbs, so I hope Mansfield subverted a few expectations with “The Little Governess”. The outcome for the young main character is not good, but not in the way audiences have been led to expect. The threat of sexual violence is isolating in its own right; against the Harlot’s Progress plot, this is a nuanced and novel psychological observation.

Contemporary readers coming to this story from literary studies may be on the look out for Mansfield’s use of parallax, thanks to the work of Julia van Gunsteren. That’s the technique this story is known for.

Van Gunsteren describes in detail this particular Impressionist technique, pioneered by Mansfield:

Mansfield’s ironic use of parallax to suggest that the man’s experience of the world is multifaceted also marks the particular modulation into a selective, restricted perspective, which is Impressionistic in concept. She employs this technique haphazardly, beginning with “How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped” (1910) and ending with “Miss Brill” (1920).

There is no consistent development. The method depends on a single device: the restricting of the perspective and knowledge of a focaliser-character into a broadening, more objective narrator’s one. He is not emotionally detached from the scene, but capable of perceiving it from a great distance. It often involves an initiation, a sudden awareness or enlightenment (epiphany) of some profound significance.

The imposition of narrative distance on a scene of intense emotional concern on the part of the participant(s) creates an irony of perspective which often suggests the isolation of individual human beings, their lack of consequence in the universal flux of life, their diminutive significance as seen from a superior vantage point and their defiant private inflation of the significance of their own lives and the events that surround them.

One of the best examples of this method can be found in “The Little Governess”, where the nameless, inexperienced young governess is made aware of her fellow-travellers, of herself, and reality outside her. At the end of the story she is isolated from everyone because of her own inconsistent behaviour. She feels hopelessly insignificant and deflated by events.

Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism by Julia van Gunsteren

How is this technique useful?

Mansfield’s parallactic narration is the horror movie equivalent of a follow shot. A follow shot allows an audience to see why a character makes their decisions, but we also see slightly more widely than they do. We see what’s coming (or what might be), but we are on this journey with them and can’t turn back. This is terrifying, for us as well as for the empathetic character. Mansfield tells the story through the eyes of the little governess, using free indirect speech. Then she pulls away and the reader sees a wider view via a more distant third person narrator. In and out, closer, further, the reader stands in judgement of the little governess, but also worries for her safety. Most significantly, we see the time on the clock. The little governess has her back to it, by design.

SHORTCOMING

The little governess is a bourgeois young woman navigating her way through urban bohemia. She is at the beginning of her life as a sexualised adult. Onlookers can intuit this by looking at her, which leaves her open to predators. In hindsight we might wonder if the old man saw her through the train window before asking the porter to let him on, and not just to avoid the crowd of rowdy young men in the adjacent carriage.

Mansfield’s carefully chosen detail indicates her youth. ‘She smiled and yielded to the warm rocking’ (as if she’s a baby on the ship). She balances herself ‘carefully on her heels’, suggesting she’s only recently started wearing the higher heels of a fashionable woman.

While narrating in free indirect discourse, the reader is told the man is very old. It’s highly doubtful that the man on the train was in his nineties. This is through the eyes of the little governess. A fact of being very young: Everyone from middle age onwards seems very, very old, lumped into the single category of ‘harmless’. But because the little governess can’t differentiate between ‘older than herself’ and ‘frail’, her imaginative powers do not stretch to the possibility that the man is a virile human being capable of ill-intent.

The little governess is especially vulnerable right now because she is in a foreign place, and until she finds her tribe, she’ll be needing help from strangers. That’s just the fact of it. When you move to a new place alone, you’re going to need people to help you out.

When the narrative camera sweeps out, we get a better look at her shortcomings. She’s a fantasist, and when fantasy starts to influence real world behaviour, this can be problematic.

DESIRE

In a melodrama, the main character has no strong desire and no strong plan. Melodrama is ‘more real’ than other kinds of stories because this is a character simply going about her life. This story scores quite high on the melodrama continuum. Things happen to the little governess, as they happen to people in real life. This main character is mimetic rather than heroic. She is not your Final Girl (Carol Clover’s term). She is just like us. She wants to get from A to B to begin her new job.

OPPONENT

Each man she encounters is a possible opponent. The first is the guard or stationmaster who touches her arm, invading her bodily space in the most minor way possible, but in a way which nonetheless counts as one of many microagressions, to use today’s language.

The porter is far more aggressive. My male friend who read this with me didn’t see much truly wrong with the porter’s actions, empathising somewhat with his desire for a decent tip. I focused instead on his aggressive actions; he ‘leapt’ onto the step of the train and ‘threw’ the money back in her lap. Worse:

For a minute or two she felt his sharp eyes pricking her all over

Can you imagine being stared down for a minute or two? This is written in free direct discourse, so may be an exaggeration, but if you were alone on a train at night in a foreign country and anyone stared you down for more than about five seconds, this is a major aggression.

The old man presents himself as an ally and is later revealed as a false ally opponent. The reader, alongside the little governess, is trying to work him out. Does he have his own evil plan in mind? However, Mansfield lets the reader know more than the little governess knows. Parallactic narration takes care of that.

Fast forward a century, American writer Gavin de Becker wrote a book called The Gift of Fear, basically telling women to trust their own instincts rather than worry about being ‘nice’ to predators.

There’s a lesson in real-life stalking cases that young women can benefit from learning: persistence only proves persistence—it does not prove love. The fact that a romantic pursuer is relentless doesn’t mean you are special—it means he is troubled.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

The old man clearly sets out to deceive her.

A drop of sunlight fell into her hands and lay there, warm and quivering. “If I might accompany you as far as the hotel,” he suggested, “and call for you again at about ten o’clock.”

The Little Governess

Though the little governess immediately sees the title on his card and draws the wrong conclusion, I’d like to point out that this man clearly has sufficient cognitive empathy to predict that this young woman might worry he wants to come into her room, so jumps in first to reassure her.

What this man lacks is affective empathy, the kind where you can put yourself in another persons’ shoes and feel what they feel. People who have plenty of cognitive empathy but are able to turn off their affective empathy are now considered to sit somewhere along the sociopathic spectrum.

The old man also functions as a fairytale trickster, wooing her with gifts; first the strawberries, then with the rose oil, a sickly sweet smell by contemporary standards, and reminiscent of a fairytale potion, foreshadowing the intoxication that is to come.

This fairytale trickster aspect of him is magnified by the creation of a fairytale setting, where ‘strange’ light from station lamps paint people’s faces ‘almost green’ (green is strongly associated with fairies). By the time the little governess has boarded the train, she has almost entered a fabulist version of a portal fantasy, or at least a heterotopia, separate from the ‘regular world’ and therefore unprotected by it. When that sign is ripped off the carriage, we know anything could happen in this strange and unusual otherworld.

PLAN

The old man has a plan. He’s an opportunistic predator. He incrementally gains her trust until he’s got her inside his room. Was he thinking more than one step ahead at any given time? Doesn’t matter. Result’s the same.

I do wonder if men who reveal their sexual intentions only after picking women off from the herd fully realise the terror experienced by the woman. We’re talking averages here, of course, but people who’ve been through female puberty have no fighting chance against people who’ve been through testosterone fuelled male puberty.

This isn’t a story about physical violence. The strength differential in this particular scenario is probably negligible. A 20-year-old woman has the upper body strength of a 60-year-old man. However, we never know someone’s true strength until it’s tested. The lack of transparency on the part of the man is hugely damaging to her psyche.

The scenario in which a man reveals his sexual intentions only after trapping a woman — or appearing to — is far more common than many would like to believe. For the physically weaker party, it’s terrifying to realise you’ve ‘misread’ the situation. When entrapment happens inside the man’s own room, she has no chance of garnering sympathy at a later date. Rape culture teaches us all that a woman who willingly goes with a man to his room, or to her room, or to any sequestered place, without being dragged, has consented to anything he desires.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

“The Little Governess” would make a case study for Gavin de Becker. The main character has been struggling throughout this entire story, trying to decide whether the old man’s intentions are noble or not. Her internalised idea of a good and generous person means she errs on the side of generosity. She wants to believe he is kind and good, and so she goes with that. She probably also mistakes niceness for some essential goodness, when de Becker urges us to consider niceness a strategy used by manipulators. Niceness is overrated:

Niceness is a decision, a strategy of social interaction; it is not a character trait.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

She goes with that summary of character against her own intuition.

It is understandable that the perspectives of men and women on safety are so different―men and women live in different worlds…at core, men are afraid women will laugh at them, while at core, women are afraid men will kill them.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

de Becker omits a major piece of the story around gendered niceness: The Incredible Double Standard Of Rudeness:

A 2015 experiment showed that when men spoke in angry tones, they came across as more credible and more persuasive. But when women spoke forcefully, they were less likely to change people’s minds. Subjects perceived the angry women as emotional and untrustworthy.

Washington Post

The rudeness disparity is well illustrated during the scene between the little governess and the waiter. The waiter is clearly incensed by this young woman, who he clearly thinks is beneath him, partly because he assumes she’s a sex worker.

He remains incensed, and the final line of the story ends with him clearly still salty about the language she used with him. He is so put out that I wondered if the governess had accidentally sounded heinously rude in her crude attempts at German, so I asked a German speaker, who replied with this:

Gehen Sie means ‘go’ or ‘go away’. This form is the most formal, a form that might be used when speaking to an underling for example a waiter. Less formal would “Gehen Sie weg” (go away) and the informal from would be “geh weg”. The c(rude) would be “hau ab” (get lost) or “verpiss dich” (piss off). So “Gehen Sie” is a form the waiter would accept if it did not come from someone he considers so clearly below him, ie. someone he considers young, female, and a sex worker.

The little governess spoke to the waiter in a perfectly acceptable way given the dynamics of her as guest, him as waiter. Clearly, a male guest might have used the same language. But from the governess it is interpreted not as a simple illocutionary act, but also as rudeness.

ANAGNORISIS

The reveal: The old fucker couldn’t be trusted. This is a plot reveal to the little governess. Via Mansfield’s parallactic shifts between free indirect discourse and more distant third person, the reader has worked it out.

Even so, when the old man pushes her against the wall, this seems like a lot. Mansfield likes to pull readers up short. So does Angela Carter. So does Annie Proulx. Why do writers do this? It’s a technique of subversion.

The real difficulty in writing this particular story probably wasn’t in depicting the character of the governess, who has few features to distinguish her from any other young woman. (This makes her as universal as possible, like Bella Swan and the Every Girl. This also explains why she remains unnamed.) The challenge in a story like this lies in characterising the old man. How to get the reader wondering alongside the governess if he’s kindly or predatory?

What idea is Mansfield subverting here? She is subverting the misconception that predators look like predators.

And how does she challenge this view?

In order to challenge this popular notion a storyteller would ideally get the reader to trust this man alongside the little governess, all the way. But this is a huge task, not least because we are reading a story. We expect bad things to happen to characters in stories. In stories we encounter baddies far more often than in real life, but the little governess doesn’t know she’s in a story. She just thinks she’s riding a damn train.

So Mansfield does it like this:

- Spend the first part of the story building empathy for the little governess. Put her in an isolated, vulnerable situation. Let us see the world through her eyes (by free indirect discourse).

- Juxtapose setting. The ship journey is a safe, cosy, feminine space. By the time the little governess gets to Germany and meets the porter, she has been thrust into a completely different world. This creates beautiful tonal contrast and retains reader interest, but also serves the story function of highlighting her vulnerability.

- Introduce the main character to an opponent who appears as trustworthy to us as to her. Make sure the reader follows the little governess, slightly outside her head but close enough that we see exactly why she made the decisions she did. The reader must understand the little governess’s decisions even when we don’t agree with them later.

- Take the ‘camera’ further away from the head of the main character. Put the reader in audience superior position by giving us the gift of hindsight: ‘It was not until long after she had said “Yes” – because the moment she had said it and he had thanked her he began telling her about his travels in Turkey…’ The third person narrator is clearly heterodiegetic, able to step outside the story, retelling events with the gift of hindsight. Writers have to be careful when using phrases such as ‘It was not long after’. Meg Wolitzer calls this technique the “Little did she know…” school of writing, sometimes utilised poorly to try and drum up suspense.

- Give details that make the audience want to say, “Nooo! Don’t follow him! He’s up to no good!” The clock, the misinformation about beer and its alcohol volume, the ‘large vase’, the intoxicated stumbles. Notice how Mansfield doesn’t let us inside the head of the little governess at this point, showing the trees wobbling, the ground moving beneath her feet (for example). We must deduce she has deliberately made drunk. When an audience must deduce, the writer is making us work, and this means we’re more fully engaged.

- Mansfield also creates in the reader a fatalistic ‘train wreck’ sensation, by literally setting part of the story on a train (often a symbol of fate), and overtly, with ‘He explained who she was to the manager as though all this had been bound to happen’.

Using the above story structure, Mansfield successfully subverts the idea that nice people are good people.

The little governess is conditioned by her environment to view an old man as harmless, and to extend kindness to a stranger who seems friendly. But like many of Mansfield’s characters, she is prone to distortion and misinterpretation. The little governess is Unreliable. This isn’t because she’s being deliberately deceitful — it’s only because she doesn’t yet understand herself or her relationship to her world. She genuinely believes kind acts mean kind people. The central issues of Literary Impressionism are ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What is happening now?’ By creating an innocently unreliable narrator, Mansfield leaves it up to the reader to piece together fragments and come to our own conclusion about the old man’s intentions. The little governess can’t see the full picture because she is stuck within the story. (This is also how Mansfield avoids didacticism.)

In Katherine Mansfield: A study of the short fiction, J. F. Kobler expresses irritation at the ending of this story, which ‘abandons’ the governess and leaves the reader equally abandoned:

Mansfield seems to leave the girl there with no hints to the reader as to what her next step may be. Of course, the little governess may well have no idea what she is going to do, with little money in a strange country and her promised job apparently gone, but the reader should have received from the construction of the story some information on which to base a judgment about what happens next. In a story in which most readers are probably two or three steps ahead of the innocent girl in figuring out what is going to happen next, it seems unsporting of Mansfield to leave her readers in the same condition she leaves her little governess. No one learns anything from the experience.

J. F. Kobler

Kobler seems to have wished for plot closure. He wants to know what happens to her next, regarding the job. He thinks she deserves the final word, at least.

Whether or not the governess has lost her chance at employment is beside the point. Her world has changed forever, regardless. Her innocence is gone. The story achieves emotional closure.

NEW SITUATION

Most young women have an encounter like the one depicted in this story, or many: A man seems friendly and reasonable, then later reveals his sexual intention only after separating her from the herd. Or perhaps he approaches precisely because she’s already separated. Perhaps he tipped the porter to let him into her carriage.

What happens after an event like this? Well, mostly nothing. Nothing happens. The woman comes out of that situation — sometimes assaulted, sometimes not — and, most often blames herself for failing to intuit the man’s intentions. She will be more wary in future.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

A requisite of melodrama: A character is in crisis. Although “The Little Governess” ends with the main character escaping rape, we can’t underestimate the consequences to this young woman’s life had she been overpowered by the man and, let’s say, become pregnant. For the little governess, in this era, life as a bourgeois woman would have ended.

Physically, this was a narrow escape.

But the emotional consequences will be significant. The governess will never forget this experience. It may have even affected her chance of an independent income.

If this young woman were like Leila in “Her First Ball“, she’d put this nasty encounter with a predatory old man right out of her mind and get on with enjoying life. Sometimes in short stories characters seem to have an epiphany, but then it doesn’t stick. We see this a lot in the Impressionist tradition, because Impressionists didn’t really believe people changed all that much, and if they did, it wasn’t in a single day. How many epiphanies do we have over the course of a lifetime? Not many, really. Character arcs don’t happen via a series of Joycean epiphanies.

Far more likely in the case of the governess: A series of similar encounters will transform this young woman from a femme seule into a cautious and wise dame seule, until eventually she’ll feel a deep simmering fucking rage if someone rips the ‘Women Only’ sign off a train carriage. She’ll avoid the gaze of creepy old men smiling in her direction; she’ll question the intent of any man who extends a favour. This is a very lonely way to be in the world. It’s hugely isolating.

The theme of loneliness is underscored from the beginning of the story. For example:

People began to assemble on the platform. They stood together in little groups…

Mansfield clearly understands that one’s own loneliness is magnified when surrounded by groups of people who know each other.

At the end of the story, the little governess is utterly alone, without even the money to get back to where she came from. The story will come full circle in other ways, too, and my experience of this plot is circular. I see the little governess and the lady at the Governess Bureau as the same woman at different times of her life. (Alice Munro uses this old woman/young woman reflection trick a lot — she’s probably got me trained.) The old and young woman together point to the ‘cycle of life’, achieving a kind of Overview Effect, showing that the experience of this particular girl is the experience of women everywhere, throughout time.

Eventually, I deduce, this aged governess will be advising younger women against getting out of their carriages, walking about in, corridors and in turn urging them to always lock their lavatory doors, should they need to use them. (Of course people need to use lavatories. That little flourish should cue us into the absurdity of heaping responsibility upon women.)

Even if the little governess sorts out her work situation, the job of governess was notorious for putting young women in a vulnerable position. They were often well-educated women from families living in genteel poverty, forced to travel far from their social network in order to earn money. On the job, there was no separation between home and work; she was fully reliant upon the same family for all necessities. Other house servants had each other. The housekeeper looked out for the novice cook, ideally. But a governess existed outside this network, dangerously alone in the household. We can only hope her employers treated her with respect.

“The Little Governess” exists as a short story to offer readers a scenario of fictionalised but plausible specifics, answering the question, “How didn’t she know?”

RESONANCE

In Europe at that time, young women traveling alone attracted attention. The sight was unusual. Unfortunately the experience of traveling alone as a young woman hasn’t changed much.

However, the blame has shifted slightly away from people who willingly consent to one thing (advice, company, tea) then find themselves vulnerable to a predator who finally removes the mask.

The #MeToo movement has helped a little with that. But among Mansfield’s contemporary readership, few would have understood how an ‘innocent’ young woman could so naively find herself in the private chambers of a sexual predator. She must be partly to blame, right? “The Little Governess” is an exploration into the psychology of how that scenario might play out, and I hope it functioned as an advice column because in 1915 there was precious little out there saying this:

Predators don’t look like predators.

You are never to blame for thinking the best of someone.

If something similar ever happened to you, it’s not your fault, and you’re absolutely not alone.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The little governess encounters a variety of different men on her mythic journey: An intimidating porter, rowdy young men in a pack, a waiter who dismisses her with a measure of disgust, and a trickster grandfather who is an outright predator. All of these men participate in the woman’s discomfort, even if innocently.

Likewise, modern crime stories are sometimes about women’s encounters with a spectrum of men, who each sit at a different point on the spectrum of culpability. One standout example is Happy Valley. (The crime genre’s willingness to delve into this #NotAllMen but #YesAllWomen issue partly explains why modern crime appeals especially to a female audience.)

Modern crime stories aside, stories about men and morality have existed for thousands of years. Some versions of the Rumpelstiltskin fairytale also encourage the reader to ask who is the most culpable of the men: the unloving father, the trickster dwarf or the greedy king? (Patriarchal re-visioners of “Rumpelstiltskin” encourage the audience to blame the young woman for her laziness.)

Mansfield also posits a chance encounter on a train as fatalistic and ‘bound to happen’ in “Something Childish but Very Natural“, in which another young woman trusts a man. Yet the outcome is totally different. When taken as a diptych with that story, we may judge the little governess less harshly. For all she knew at the time, her friendship with this old man may have proved beneficial and beautiful to them both.

Madame Tutli Putli is a short horror film about a woman who boards a train alone, at night, encounters scary men and, well… it ends worse than The Little Governess, but the emotions are similar.

Header painting: George Dunlop Leslie – Roses (1835-1921).