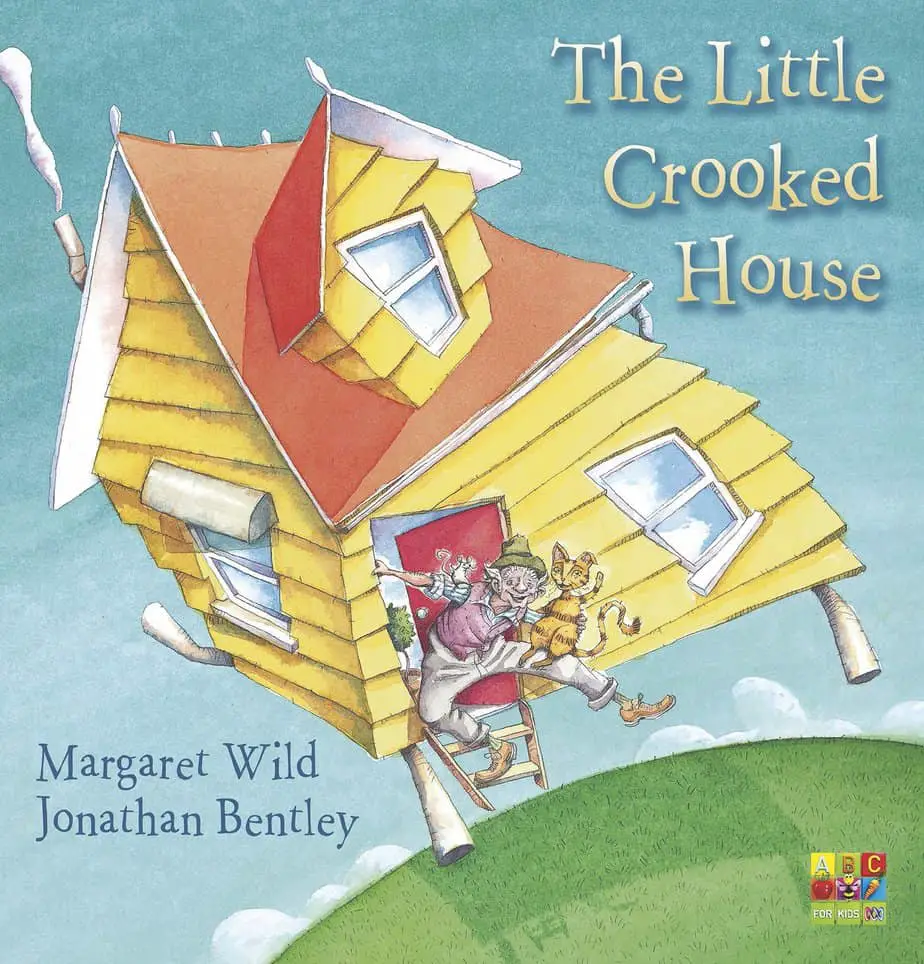

The Little Crooked House (2005) is an Australian picture book written by Margaret Wild and illustrated by Jonathan Bentley who, coincidentally, has the perfect name for this story, gotta say.

Though made here in Australia, this picture book kicks off with a very old Mother Goose nursery rhyme and goes from there. From a storytelling perspective, Wild’s expanded version of “The Little Crooked House” makes for a great case study in how to utilise a folk song from antiquity and turn it into something new, for a contemporary audience. Margaret Wild is similar to Britain’s Julia Donaldson, in her ability to weave new stories using very old tropes. See, for instance, Stick Man.

This one starts off with Mother Goose then sprinkles in tropes from The Gingerbread Man and Baba Yaga. Modern audiences will notice that Howl’s Moving Castle and Pixar’s Up borrow from the same traditions. Unlike Julia Donaldson’s Stick Man, The Little Crooked House dispenses with rhyme as soon as the actual Mother Goose part is over (the first page). It is totally okay not to rhyme! (I suspect some new picture book authors almost need overt permission not to…) If The Great Margaret Wild didn’t feel the obligation to carry on a difficult rhyme scheme, no one else should feel obliged to do so, either.

Wild utilises what we might call ‘folktale’ language, more generally. For instance, the phrase ‘over the sand dunes and far away’ is a riff on ‘over the hills and far away’, which comes from Tom, Tom The Piper’s Son (or even earlier). In this way, picture book authors can create beautifully rhythmic sentences without the need for rhyme. (There’s more than one way to skin a crooked cat. Okay, sorry.)

The Little Crooked House by Wild and Bentley is also noteworthy because it’s one of those stories which will leave young readers with a very different ending from adult co-readers, and not because there’s a symbolic layer a la John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat, but because adults know more about the world — specifically, how land ownership works.

SETTING OF THE LITTLE CROOKED HOUSE

According to Wikipedia…

The rhyme was first recorded in print by James Orchard Halliwell in 1842:

There was a crooked man, and he went a crooked mile,

He found a crooked sixpence against a crooked stile;

He bought a crooked cat, which caught a crooked mouse,

And they all liv’d together in a little crooked house.

The Wikipedia article also grounds this story in a particular political and economic climate (the end of the 1600s). The detail about the crooked sixpence feels like oddly specific absurdism until we learn that ‘The great recoinage around 1696 led to sixpence coins that were made of very thin silver and were easily bent, becoming “crooked”.’

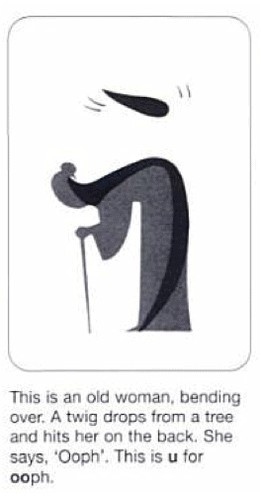

I’m just old enough to remember seeing elderly people during childhood who were literally bent right over. This was especially noticeable when I was an exchange student in Japan in the late 90s — dietary deficiencies created a generation of people (especially women), some of whom made it to an advanced age, but with highly compromised skeletal structures. When I learned (and later taught) the Japanese hiragana syllabary, the picture mnemonic for ‘u’ is literally a picture of a bent over elderly woman.

The sight of ‘crooked’ elderly people in rich countries is (fortunately) quite foreign to most young contemporary readers, who won’t be thinking of osteoporosis and other diseases when they see this ‘crooked’ old man.

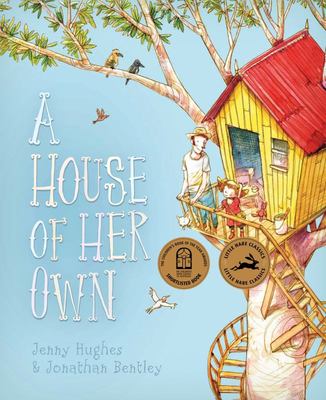

When illustrating The Little Crooked House, Jonathan Bentley has made the entire world look crooked. The off-kilter perspective is especially obvious when compared to another of his books, with a similar palette and art style, but without the crookedness:

Part of the ‘crooked’ feel of this setting is achieved by utilising what I call the ‘cosy little world‘ horizon line (for lack of an established term), in which the illustrator curves the horizon to make the world look very small. This also has the effect of making a world look cosy, and is especially well-suited to picture books for a very young audience, whose worlds are very small (mostly limited to the home and neighbourhood).

The crookedness of the story is even evident in the font. I’m not sure how eemergent readers would cope with deliberate messing around with baseline alignment of text. This is a good reminder that picture books for preschoolers are created with an adult co-reader in mind. (Texts for emergent readers — ie. early chapter books — can’t so easily get away with that kind of thing.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE LITTLE CROOKED HOUSE

I can’t make up my mind whether to use the ‘mythic‘ or ‘carnivalesque‘ template when taking a closer look at the plotting of this story, and that’s because it’s both. Carnivalesque stories are all about getting rid of hierarchies for a bit and having fun. (Odyssean) mythic stories are all about going on a journey and either returning home afterwards or finding a new home.

PARATEXT

There was a crooked man who lived with a crooked cat and a crooked mouse all together in a little crooked house. Their happy existence is unsettled by a noisy train that passes close by each day, shaking the house and its inhabitants: “Shucka-shucka, shucka-shucka, shucka-shucka!” Literally refusing to stand still for this, the crooked house does the unthinkable! This charming picture book, with its whimsical image of a moving house and the repeated refrain of “Yippee-yi-yay!,” encourages young readers to interact. Jonathan Bentley’s vibrant watercolor illustrations add to the fun.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

But the little crooked house had been built on the edge of a railway track.

This is why the crooked old man and his crooked cat have to move. “One of these days we’ll be shaken to bits,” he exclaims. Perhaps this is the story’s reason for how this old man and his cat became crooked in the first place. They’ve been shaken crooked by the train.

DESIRE

The crooked old man wants to find a place to live where there is no train bothering them.

OPPONENT

The noisy train.

Along the way, the crooked old man and crooked cat meet playmates rather than opponents e.g. in the desert, the cat plays with the desert mice as playmates.

The weather also functions as opposition, with hot winds piling sand around the little house, making it difficult to move, and a flooded river. (This is in some ways a very Australian setting. Australia can be both flooded and on fire in the same week.)

PLAN

Now the story switches to carnivalesque mode, which means there’s no real plan as such; the characters are having fun.

The phrase yippee-yi-yay is a giveaway. Kate diCamillo also uses this in one of her Mercy Watson stories (the one with home intruder Leroy Ninker). But then, even the Die Hard franchise utlises the catch phrase yippee-ki-yay (ironically, since Die Hard can’t really be classified as ‘harmless fun’). If you’re wondering where this phrase comes from:

The yip part of yippee is old. It originated in the 15th century and meant “to cheep, as a young bird,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The more well-known meaning, to emit a high-pitched bark, came about around 1907, as per the OED, and gained the figurative meaning “to shout; to complain.”

A brief history of yippee-ki-yay, The Week

THE BIG STRUGGLE

With carnivalesque hi-jinks, the fun reaches a peak, which often means the picture book gets more and more ridiculous. Views of the house interior shows everything rattling and toppling as the house runs.

In this case, most of the ridiculousness derives from the imagery of a house which runs. Storytellers have been milking this one for generations, hence why Baba Yaga lives in a house with chicken legs. A detail like this sticks in the mind and survives centuries of storytelling. Another good example is the glass slipper of Cinderella, which may have accidentally entered the story due to a miss-in-translation. (It’s surprising how much resonant folk- and fairytale imagery involves the feet.)

ANAGNORISIS

There’s a double-page spread which functions like a Where’s Waldo page. The young reader will enjoy finding the little crooked house in the establishing shot of the city.

It’s interesting that, in this story, a ‘happy’ ending for the main characters means moving from a more rural setting to a very urban one. Across the history of children’s literature, it more often works the other way. Children move from the city to the country and enjoy a more wholesome life. I certainly grew up with that view, because about half of my reading diet comprised Enid Blyton. Storytellers from the Second Golden Age of Children’s Literature commonly villified children who had been acculurated in the city and glorified children who’d been brought up in the country. (Take Connie versus Jo, Dick and Fanny in The Faraway Tree series as an excellent example.)

NEW SITUATION

Child readers will be happy to see the little house tucked away snug between two larger houses. The entire setting of this picture book has been brought to life, with animism in the landscape and a very storybook view of the world. So young readers will code the little house as ‘child’ between two caring parents.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Of course, adult readers might think to themselves, “Hang on. You can’t just plonk a house in someone’s yard and expect a happily ever after.”

RESONANCE

It’s always fascianting to see how contemporary storytellers take very old tropes and craft new stories from them. There’s nothing in this story that’s new, but taken as a whole, this particular plot hasn’t been seen before. ♦