I keep saying that Katherine Mansfield is a standout example of a Modernist short story writer, but what does ‘modernist’ really mean?

“Make it new!”

EZRA POUND, 1934

The Modernist Timeline

In Wharton and in James, we see the formal precepts of realism taken to their absolute limit—the breaking point before modernism. The traditional nineteenth-century novel aspired, for the most part, to reflect the world objectively. Stendhal famously wrote that the novel is a mirror carried along a road, which sums it all up.

But toward the end of the nineteenth century, I think many novelists were turning that mirror away from the road and toward its bearer. Who is looking at the world and how is this observer, too, part of the picture?

Eventually, the mirror shattered and the novel found itself looking at the scattered reflections on the shards. As literature no longer was required to reflect a cohesive, unified world, the gaze also began turning inwards.

I’m abusing Stendhal’s simile and presenting all this in a rather schematic, linear fashion. But I think that toward the end of this trajectory, where I would place James and Wharton, the novel is trying to do things that were unimaginable a few decades earlier.

Hernan Diaz

Where does the word come from? The word modernism first appeared in 1737, and kept shifting in meaning. For a long time it meant “a sense of forward-looking contemporaneity” (Modernism: Designing a New World by Christopher Wilk, 2006)

The trouble with declaring something ‘modern’ is that it can never be modern for long.

We’ve now settled on a static meaning of Modernism. The word now refers to specific types of art which appeared at the end of the 18th century and into the 19th.

What was happening around this time? Tom Gibbons studied the sources of Modernism and defined the first decades of the 20th century as:

religiously, a belief in some sort of mysticism; politically, a belief in the desirability of an elite social class; aesthetically, a strong leaning towards transcendental and anti-naturalistic theories of art and literature.

Tom Gibbons, Rooms in the Darwin Hotel, 1973

Although Modernism is no longer ‘modern’, the movement distinguished itself by going out of its way to be different from what came before. Modernists went out of their way to be modern. So the name still fits.

There is no consensus about when Modernism began as a movement. But hindsight gives us a ballpark date range. Let’s say Modernism happened between the late 19th century until the beginning of the second World War. (Okay, let’s say a nice tidy 1940.)

Magazines were essential to the rise and maturation of Modernism.

Novels like Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse (1927) and James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) are tentpole examples of Modernist novels. These stories emphasise fictitiousness. These artists believed that any attempt at representing ‘reality’ could only go so far. That’s because they believed there is no such thing as reality. There are only selective perspectives of reality.

“He pilfered a copy of Ulysses, but it was possibly the one book he did not finish. ‘What’s the point of it? I suspect it was a bit of a joke by Joyce. He just kept his mouth shut as people read into it more then there was. Pseudo-intellectuals love to drop the name Ulysses as their favorite book. I refused to be intellectually bullied into finishing it.”

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

On James Joyce’s “Ulysses”: A Discussion with Catherine Flynn

Perhaps more than any other book, Ulysses has the reputation of being difficult—it is dense, allusive, and often hard to follow. But Joyce wasn’t trying to be challenging for its own sake, or because he sadistically wanted to punish future students assigned his book. Quite the contrary. With Ulysses, Joyce wanted to explore and convey what it is to be alive. And just like his book, life is difficult and confusing, but also thrilling and joyful. Catherine Flynn is Associate Professor, Affiliate of the Program in Critical Theory, Director of Berkeley Connect in English, and Director of Irish Studies at the University of California Berkeley. She is the author of James Joyce and the Matter of Paris. See more information on our website, WritLarge.fm.

New Books Network

The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses

From the creator of UlyssesGuide.com, The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses (Johns Hopkins UP, 2022) weaves together plot summaries, interpretive analyses, scholarly perspectives, and historical and biographical context to create an easy-to-read, entertaining, and thorough review of Ulysses. In The Guide to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses,’ Patrick Hastings provides comprehensive support to readers of Joyce’s magnum opus by illuminating crucial details and reveling in the mischievous genius of this unparalleled novel. Written in a voice that offers encouragement and good humor, this guidebook maintains a closeness to the original text and supports the first-time reader of Ulysses with the information needed to successfully finish and appreciate the novel.

Deftly weaving together spirited plot summaries, helpful interpretive analyses, scholarly criticism, and explanations of historical and biographical context, Hastings makes Joyce’s famously intimidating novel-one that challenges the conventions and limits of language-more accessible and enjoyable than ever before. He unpacks each chapter of Ulysses with episode guides, which offer pointed and readable explanations of what occurs in the text. He also deals adroitly with many of the puzzles Joyce hoped would “keep the professors busy for centuries.” Full of practical resources-including maps, explanations of the old British system of money, photos of places and things mentioned in the text, annotated bibliographies, and a detailed chronology of Bloomsday (June 16, 1904-the single day on which Ulysses is set)-this is an invaluable first resource about a work of art that celebrates the strength of spirit required to endure the trials of everyday existence. The Guide to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ is perfect for anyone undertaking a reading of Joyce’s novel, whether as a student, a member of a reading group, or a lover of literature finally crossing this novel off the bucket list.

New Books Network

The Cambridge Centenary Ulysses: The 1922 Text with Essays and Notes

James Joyce’s Ulysses is considered one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century. The Cambridge Centenary Ulysses: The 1922 Text with Essays and Notes (Cambridge UP, 2022) – published to celebrate the book’s first publication – helps readers to understand the pleasures of this monumental work and to grapple with its challenges. Copiously equipped with maps, photographs, and explanatory footnotes, it provides a vivid and illuminating context for the experiences of Leopold Bloom, Stephen Dedalus, and Molly Bloom, as well as Joyce’s many other Dublin characters, on June 16, 1904. Featuring a facsimile of the historic 1922 Shakespeare and Company text, this version also includes Joyce’s own errata as well as references to amendments made in later editions. Each of the eighteen chapters of Ulysses is introduced by a leading Joyce scholar. These richly informative pieces discuss the novel’s plot and allusions, while also explaining crucial questions that have puzzled and tantalized readers over the last hundred years.

New Books Network

Katherine Mansfield was a ground-breaker in Modernist short stories. Mansfield was publishing throughout the 1910s, into the 1920s. (She died of tuberculosis in 1923.)

CULTURAL FORCES

Many cultural forces led to the art movement of Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th century:

- Industrialisation

- Urbanisation

- Immigration

- Commodification

- Mass production

Then World War 1 happened, with its catastrophic violence. This had an impact on art movements, too.

After WW1 there was increased emphasis on the subconscious. Sigmund Freud had something to do with that.

THE INFLUENCE OF SCIENCE

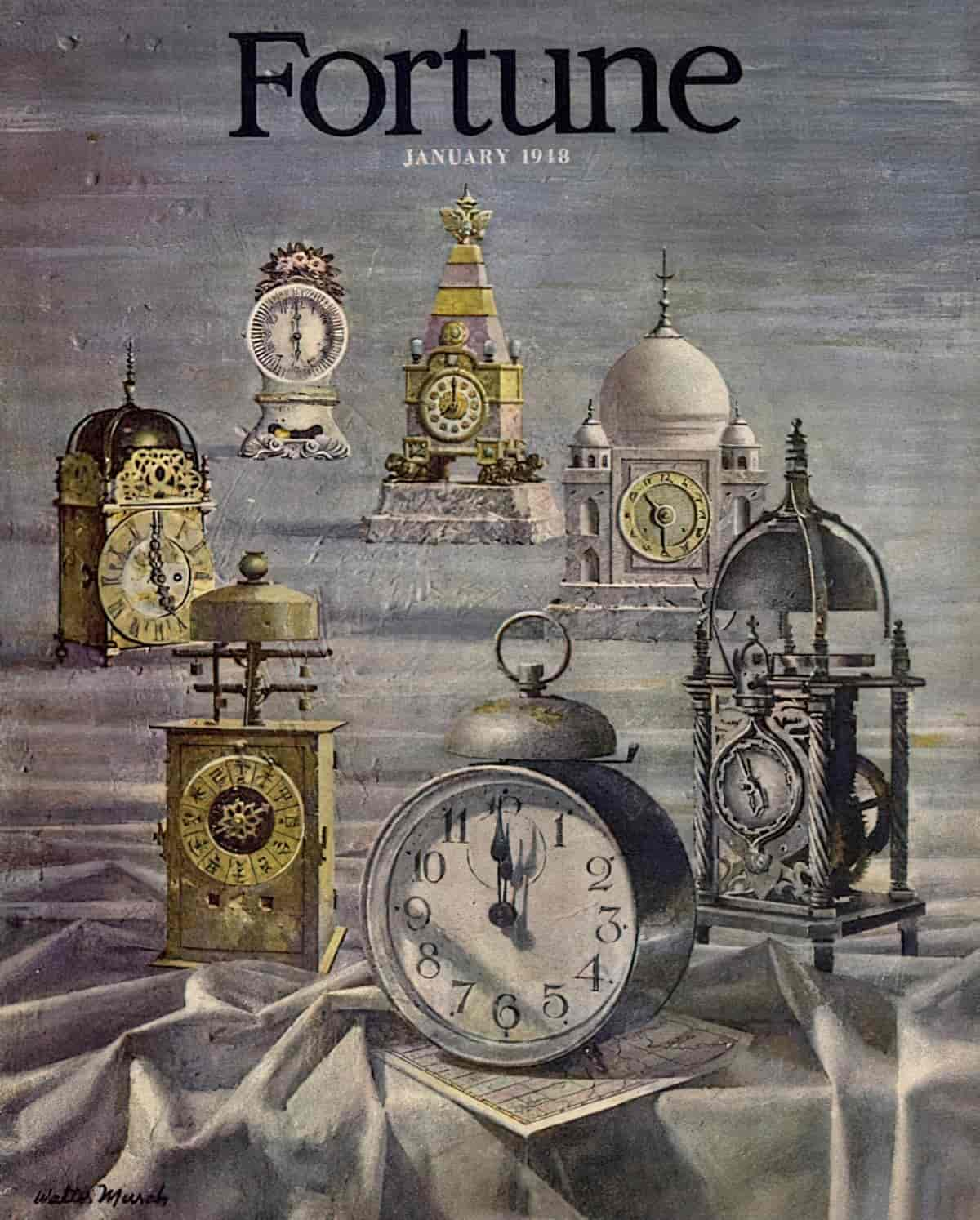

Einstein worked in a completely different field, but Einstein’s theories had a big effect on art, as well as on science. Writers were thinking a lot about our notion of time around the publication of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. This was mind-blowing stuff for everyone who learned about it. Time doesn’t fly like an arrow! Who knew?

Virginia Woolf captured how Einsteinian relativity feels.

As a result, literary Modernists treat time in a circular way rather than linear.

Modernist artists, along with their audiences, felt like they were living in a world that was changing very quickly. When people feel things are moving too fast, we tend to lose confidence in institutions and social conventions which gather us together in an ordered way.

We also tend to feel like puppets — that things are happening behind the scenes and we have no control. War doesn’t help.

THE INFLUENCE OF VITALISM

Vitalism is the belief that “living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things” (William Bechtel, Robert C Williamson, 1998).

Vitalism affected how Modernist writers viewed ‘character’. Modernist writers radically probed the nature of selfhood. Before, the self had been understood in terms of a single transcendent ego, but Modernists put it to their readers that ‘self’ was not only multiple, but also mutable. The self is not one, single, never-changing thing. We change from moment to moment, as situations change.

A vitalist worldview for artists meant they viewed character as both individuated and also as a part of a complex whole. This relationship is dynamic, in motion and constantly transforming.

Which art movements CAME right before Modernism?

Well, there were a few going on all at once, all related to each other:

Realism: Late-19th-century movement based on a simplification of style and image and an interest in poverty and everyday concerns.

Naturalism: Late 19th century. Promotes the idea that heredity and environment control people.

Verismo: An Italian derivative of Naturalism and Realism. Verismo literature uses detailed character development based on psychology, “The science of the human heart” (Giovanni Verga).

Socialist Realism: A Soviet Union subset of Realist art which focuses on communist values and realist depiction.

Magical Realism: Magical elements appear in otherwise realistic circumstances. Most often associated with the Latin American literary boom of the 20th century. Some argue that magical realism should only apply to works which come from Latin America, and everything else labelled ‘fabulism’.

So basically, Realism and Naturalism precede Modernism. These forms of art both come from a firm belief in a commonly experienced, objectively existing world of history. Deliberately distancing themselves from Realism, Modernists got rid of the idea that there is any sort of veridical ‘reality’ within the world of a story.

Realist writers had clearly been trying to ‘out-real’ each other, in a competition to see who could write the most realistic stories. They were going for verisimilitude, and hoped readers could feel like they were ‘really there’, in the world of the story. Modernist artists disputed the very notion of ‘real’, so ‘verisimilitude’ can’t be a thing, either.

OTHER ART MOVEMENTS WITHIN MODERNISM

Within Modernism we find a bunch of other -isms. Overall, Modernist movements are about getting to some deeper truth, to a ‘realness’ beyond the movements within Realism:

- Surrealism: Despite how this word is used in colloquial modern English, surrealism is about the ‘super real’. (It means super real in French.)

- Imagism: a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precise imagery and clear, sharp language.

- Expressionism: arose as a reaction against materialism, complacent bourgeois prosperity, rapid mechanization and urbanization, and the domination of the family within pre-World War I European society. Expressionism was the dominant literary movement in Germany during and immediately after World War I.

- Vorticism: flourished in England in 1912–15. Founded by Wyndham Lewis, it attempted to relate art to industrialization. It opposed 19th-century sentimentality and extolled the energy of the machine and machine-made products, and it promoted something of a cult of sheer violence.

- etc.

WELL-KNOWN MODERNIST WRITERS

Notice how many of those Modernist authors also wrote for children, or with a childlike view of the world. No accident here — a childlike viewpoint allowed adult writers to experience the world of adults in a deliberately defamiliarising way:

- Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923) who became more Modernist as she matured and was a leader in the tradition.

- D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930 who just so happened to be a friend of Katherine Mansfield

- Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) another of Mansfield’s closest friends and one of only two people who neither ‘loved’ nor ‘despised’ Mansfield, but who instead saw her complicated humanity. (The other was D.H. Lawrence.) Virginia Woolf founded The Bloomsbury Group in 1912 with her husband Leonard in Gordon Square. This group of artist friends flourished through the first two decades of the 20th century.

- William Faulkner (1897-1962)

- Henry James (1843–1916) who wrote a famous story from the viewpoint of a young girl, depite being well-known for not thinking much of children.

- James Joyce (1882–1941) who wrote Ulysses, and also A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, with emphasis on ‘a portrait’ (meaning there are others, this is just one possible take on the guy). Finnegans Wake is also well-known, mostly for being a super difficult read.

- T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) who wrote OldPossum’s Book of Practical Cats

- E.E. Cummings (1894-1962) who wrote His Whist and Other Poems and who was clearly inspired by a childlike perspective.

- Lewis Carroll (1832–1898) considered by some, e.g. Juliet Dusinberre, the forebearer of literary Modernism.

- Langston Hughes (1901-1967) who wrote for adults and children e.g. Popo and Fifina (1932)

- Hilda Doolittle (1886–1961)

- Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) who wrote The World Is Round.

- Henry Roth (1906–1995) who wrote Call It Sleep.

- Mina Loy (1882–1966) who wrote Anglo Mongrels and the Rose.

No Modernism Without Lesbians

Diana Souhami talks about her new book No Modernism Without Lesbians, out 2020 with Head of Zeus books.

A Sunday Times Book of the Year 2020. This is the extraordinary story of how a singular group of women in a pivotal time and place – Paris, between the wars – fostered the birth of the Modernist movement.

Sylvia Beach, Bryher, Natalie Barney, and Gertrude Stein. A trailblazing publisher; a patron of artists; a society hostess; a ground-breaking writer. They were all women who loved women. They rejected the patriarchy and made lives of their own – forming a community around them in Paris. Each of these four central women interacted with a myriad of others, some of the most influential, most entertaining, most shocking and most brilliant figures of the age. Diana Souhami weaves together their stories to create a vivid moving tapestry of life among the Modernists in pre-war Paris.

New Books Network

FEATURES OF A MODERNIST STORY

Modernism is based on a utopian vision of human life and society and a belief in progress.

- Language has multiple meanings. (Writers are concerned with the problematic relationship between language and meaning.)

- Writers reject realism.

- Narratives tend to be experimental and nonlinear. (Chronological linearity? Ugh!)

- Ironic juxtapositions are frequent.

- Writers deliberately obscure meaning.

- Writers are preoccupied with the destabilizing forces of science and technology.

- Stories commonly feature interior monologue and stream of consciousness narration

- Stories are frequently written from multiple points of view.

- Stories demonstrate a self-conscious concern with the nature of writing itself.

- Writers don’t define characters by their age, life circumstance or physical appearance, but rather by their ‘voice’. This voice stands in for the self.

FEATURES OF MODERNIST CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

For a long time, the consensus seemed to be this: After the catastrophic first World War, writers for adults confronted changes head on. In contrast, writers of children’s literature had their heads in the sand. They decided children needed nice stories set in Arcadia.

Head in the sand stories set in Arcadia are plentiful in the post World War period, for sure. But it’s a mistake to think Modernism didn’t touch children’s literature. It did. Especially when you consider how many writers for children were also writing Modernist stories for adults. (Lewis Carroll is widely considered the forbearer of literary Modernism in general, not just ‘Modernism for Children’.)These authors understood self-doubt, ambiguity and uncertainty. They didn’t want to pacify children by telling them the world is black and white.

In short, children’s literature is as progressive as stories for adults.

Modernist children’s literature has basically the same features as Modernist stories for adults, but it’s worth pointing out a few extra features:

- Gender construction is a theme, with child characters pushing back against gender norms

- In children’s modernism, storytellers disrupt the myth of Arcadia.

- Loss of faith

- Rejection of Victorian narrative conventions, with rebellious and naughty children

- Linguistic playfulness and experimentation

- Meaning is subjugated to sound

- Stories don’t make a clear distinction between the real and the imagined

- Characters are often searching for a stable concept of self (and usually don’t find it)

STANDOUT POSTMODERN CHILDREN’S AUTHORS

All of these authors were pushing the boundaries of what adults considered acceptable for children to read. They encouraged young readers to explore complex issues around self-perception. They knew that children, like adults, struggled to make sense of the new and chaotic modern era.

- P.L. Travers, who wrote Mary Poppins

- Oscar Wilde

- E. Nesbit, who changed children’s literature for good

- John Masefield (The Midnight Folk, The Box of Delights)

- James Barrie (Peter and Wendy)

- Astrid Lindgren (Pippi Longstocking)

- A.A. Milne: Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh calls attention to its own artifice, experiments with language, works on two different diegetic levels, and challenges the boundaries between imagination and reality. He focuses on the interiority of several different characters, suggesting multiple points of view and ways of viewing a situation. There’s an ironic distance between text and illustration, which always offers an alternative view on the story by means of parallax. Milne is well aware of a child’s egocentricity, despite the surface Romanticism. He’s also borrowing from the Victorian nonsense tradition.

MODERNIST NARRATION

Before modernism came along, realist writers made use of narrators to explain things to the audience with off-stage asides. Modernist writers got rid of this commentary, letting readers interpret for themselves. Modern audiences expect not to have our hands held. We will only accept commentary when it is offered ironically (e.g. the end of SpongeBob Squarepants and Modern Family episodes).

Because the reader is expected to do more work, the narrator of a Modernist story is more of an observer, acting more like a camera than a professor.

In general, Modernist narration tends to be third person with one focalising character. Sometimes this focalising character shifts, sometimes roving all over the place. Multiple focalisation allows the reader into the heads of multiple characters which is better when your politics are against coming down in definitive judgement. (The problem with close focalisation of a single character is, readers are like ducklings and tend to side with that first character.)

THE IDEA OF FRAMES

Patricia Waugh says in Metafiction: the Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction (1984) that Modernism and Post-Modernism begin with the view that both the historical world and works of art are organized and perceived through what she calls ‘frames’.

Waugh argues that “Everything is framed, whether in life or in novels.” (So let’s not make the mistake of thinking that we can divide works of art into ‘framed’ and ‘unframed’.)

Ortega y Gasset, writing on Modernism, made the observation that “not many people are capable of adjusting their perceptive apparatus to the pane and the transparency that is the work of art. Instead they look right through it and revel in the human reality with which the work deals”.

You may be familiar with the idea of ‘frames’ when talking about contemporary metafiction. You may also be familiar with diegetic levels, in which narratologists talk about ‘level zero’ (designating ‘zero’ as ‘the main’ story), with hypodiegetic layers below and metadiegetic layers above. This is another way of talking about how storytellers frame their stories.

Metafiction asks the audience to consider, “What is the ‘frame’ that separates reality from ‘fiction’? Is it more than the front and back covers of a book, the rising and lowering of a curtain, the title and ‘The End’?” (Patricia Waugh, talking about peritext).

The notion of frames and diegetic levels jibe with the Modernist worldview: That everything is seen through some sort of frame; there is no such thing as veridical reality.

NARRATED MONOLOGUE

Some have called the writing style of Mansfield, Lawrence and Woolf ‘narrated monologue‘. In this style of narration, the reflecting mind is presented in the third person and in the preterit (denoting events which took place or were completed in the past).

In English the preterit means the simple past tense (verb-ed). (In English the simple past does not not always express the perfective — over and done with — aspect.)

German speakers have a word for this style of narration: erlebte Rede. It refers to a rendering of a character’s thoughts in their own idiom while maintaining the third-person form of narration. Narrated monologue is different from interior monologue because it maintains ‘the person and tense of authorial narration’.

PHENOMENOLOGICAL AESTHETICS

What replaced attempts at verisimilitude? What do we call it, if the artist is not even going for ‘real’?

Some have called its replacement ‘phenomenological aesthetics’, which draws a distinction between ‘real objects’ and ‘aesthetic objects’. The reader experiences a real object aesthetically. The reader reconstructs. In short, the reader does part of the work of constructing a story.

Modernist writers send the readers off in search of meaning. This offers readers more chance of coming to grips with their own ideas. Modernists are not didactic. They want readers to think, but they don’t want to tell them the content of what to think.

A MODERNIST TREATMENT OF TIME

TICK-TOCK-TICK PLOTS

The plot of a typical Modernist story has been described by Frank Kermode as tick-tock-tick. Kermode’s most influential book is The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theories of Fiction.

Kermode argued that fiction gives shape to time by translating the relentless tick-tick-tick of bare chronicity into the tick-tock of a meaningful plot. By listening for the next tick as a tock, as the end of something that preceded it rather than the next in a meaningless and interminable succession, we invest time with shape and significance. And if tock is a tiny apocalypse, the end of a millennium ought to be a very big one.

Malcolm Bull, The Guardian

Kermode makes a distinction between the ‘reality’ of chronos (tick-tick) and the ‘time-redeeming’ kairos (tick-tock).

(Remember, since Einstein was making people scratch their heads about the meaning of time, this was reflected in art.)

Realist writers tended to tell a story ‘from start to finish’ (though plotting rarely maps completely onto chronological order of a story). This is known as ‘linear’ storytelling.

In contrast with (linear) Realist writers, a significant feature of Modernist literature is the reinterpretation of and experimentation with time. Was this entirely down to Einstein et al? No, it was also Impressionism (late 19th century) plus Dadaism and Surrealism and other avant-garde movements of the first half of the 20th century that triggered this shift away from the concept of linear time in art. Sure, Einstein was a genius, but his brain came along at the exact right time. Big ideas about time were in the air, including in the art. (Art is important!)

Modernists tend to jump around a timeline when constructing a plot. In this respect, Modernist work feels more like the narrative of folklore, where the absolute chronological order is rare.

Once storytellers dispense with absolute chronological order, possibilities open up and writers become more likely to play with:

- motifs (and symbolic codes in general)

- imagery

- tropes

- antithetic pairings (and other contrasts)

These aspects of story don’t hew to chronological time. They belong to a dream space. In order to understand the symbolism of a story, the audience must consider all of the story at once. Ditto for motifs. Tropes are inherently intertextual because they are like jigsaw pieces used time and time again across storytelling, across generations.

Examples of symbolic archetypes: snakes, roses, pre-lapsarian arcadia. You know what these symbolise because you’ve come across them in stories before.

Modernists use character tropes to de-historicise the individual. According to an historicist worldview, identity is stable and a result of continuity, social and cultural phenomena are determined by history. The son is who he is because of his father and so on. Modernists didn’t think like this. They broke the ties between generations.

Tropes are the opposite of individuation. For example, in Sons and Lovers D.H. Lawrence makes use of the character tropes of Religious Woman, Passionate Sensualist and Authoritative Mother to make us think about the various ways of being a woman. But underneath the ‘masks’, these characters are thought to comprise the same basic element. The allotropic states don’t need to be embodied by the one person. (‘Allotropic’ comes from chemistry and means ‘other form’. Some chemical elements exist in two or more different forms, and the same is true for fictional characters.)

Turning now to Modernism for adults, in Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, Peter Walsh and Clarissa Walsh are allotropic states of the same basic element. They spend the entire time arguing, but this is because they are essentially the same… deep down. In Katherine Mansfield’s “The Garden Party“, we might say Laura and Laurie are allotropic states of the same person. Mansfield makes this obvious even to the more casual reader: She’s given brother and sister very similar names. We can see this in children’s literature. It’s often said that the animal characters in the Winnie the Pooh stories are allotropic states within the same child.

By making use of these tropes Modernist writers seek the fundamental facts of human existence and explore themes from birth to the grave (growing up, the experience of falling in love, the struggles between parents and children, between siblings).

Themes are also archetypes: quests, descent into underworlds, home-comings, overcoming difficult tasks. redemption.

BERGSON’S Durée AND ELAN VITAL

Duree: “subjective time”, inner experience, subjective and intuitively grasped. It is the real time we experience in our own conscious life.

In 1889, Henri Bergson wrote a doctoral dissertation called Time and Free Will, about freedom of the mind and duration. (It was translated into English in 1910). Bergson’s ideas started a lot of talk among philosophers and influenced Modernist literature.

- Bergson said there are two different ways of knowing a thing.

- Time, when considered in a rational, linear manner, is often mistaken for space. (Bergson’s entire deal is trying to get us not to always conflate time with space.)

- When we look at an analogue watch, we see the second hand moving (through space). He uses the watch as an example of how our concept of time is intimately connected to space.

- Time requires a ‘before’ and ‘after’. But what if there is no memory or consciousness? In that case, there can be no succession, and therefore no time. Without memory or consciousness, there are only single moments.

- When we think of ‘consciousness’, we tend to think of it as a series of discrete moments. But it would be more accurate to describe consciousness as a succession of moments that ‘interpenetrate each other and form an indivisible whole’. (Beasley, 2007)

- The only real time for Bergson is time which invokes a sense of timelessness.

- Human minds don’t work like a clock. We live in a kind of eternal present. Bergson calls this ‘simultaneity‘. (Again, the intersection of time and space.)

- Time may seem to function as past, present and future, but that’s not how it works at all. Time functions as one simultaneous concept, since the past affects the present and the present works with the future in mind. Past, present and future interact with and shape each other. At any given time we are experiencing the present moment, memories of the past and expectations of the future. There is no isolated linear progression. All three (past, present, future) together make up the temporal state of being.

- Duree is made up of ‘moments inside one another’ (mise en abyme style). Time is indivisible.

- When past, present and future merge, we experience a moment of transcendence, an epiphany.

- Elan vital: vital force. In Modernist work, the repressed and subjective nature of the individual is retrieved from the ‘vital forces’ of dreams, fantasies, madness and similar.

Shortly before John Berger died—a mere two days into the beginning of 2017—he had been working on a small book about time. … What Time Is It? examines the different ways we may think about what is on a chronometer: personal time, clock time, the way time bends and stretches and loop-de-loops for each of us in a unique way as we walk through the world, and how we are always walking in the shadow of our own death, whether or not we know it. Time in one place for one person is not necessarily the same as time for another, even if both may be measured by the same clock—and, of course, as Einstein famously observed, time is relative: clocks tick slightly differently, depending on how fast they are moving in space.

For John Berger, the Time We Feel Most Deeply Can’t Be Kept on a Clock, LitHub

EPIPHANIES IN MODERNIST WORK

The experience of an epiphany is a key aspect of Modernist writing: Virginia Woolf and James Joyce tried to articulate flashes of realisation, revelation, insight and understanding.

You may have noticed when reading Katherine Mansfield short stories that the epiphany is a standout point.

Since short stories are all about epiphanies, the Bergsonian way of thinking about time seems perfectly suited to the short story, and especially to Modernist short stories.

Characters move through the world wrong about something (or many things), seeing the world through a frame, failing to bring everything together. But! Near the end of the story they experience time ‘as it really is’ (according to Bergson) and for just a moment, the character experiences reality. These aren’t necessarily epiphanies per se, but more like moments of heightened awareness.

In a Mansfield short story, as often as not, the character goes right back to existing as they did before.

HOW DID MODERNIST WRITERS DESCRIBE DUREE?

Virginia Woolf described these epiphanies as ‘moments of being’, which is easier to remember than the concept of duree, but which makes more sense when understood alongside the concept of duree. (It was James Joyce who called them ‘epiphanies’ hence the oft-heard phrase ‘Joycean epiphanies’.) D.H. Lawrence used a different word again: ‘living moments’.

In these Modernist works, the epiphanies (or whatever you want to call them) generally come with some authorial commentary which tells us about the characters’ subjective perceptions.

T.S. Eliot (philosopher and poet) is considered another tentpole Modernist writer (though other movements have equal claim) and was influenced by the thought of Henri Bergson. In line with Bergson’s ideas about time, Eliot believed the past exists only in one’s current sense of it. The same is true of the future. Therefore all things, whether tangible, imagined, remembered, or anticipated, are one.

Eliot put it like this:

The past lived over is not memory and the past remembered is never lived.

T.S. Eliot, Knowledge and Experience

What we remember is never the same thing as the thing that was actually experienced by our subjective past-self. We interpret past experience with a consciousness that surrounds us in a collective mode in the present.

Note: This view of the past belongs not the subjective self but of the collective consciousness.

Time is not a sequence of one thing following another within some actual common ground. There is not a world that contains time; there is a flow of time, which produces worlds or durations. Time is a virtual whole of divergent durations. The everyday illusion is that life flows from one moment to the next and that we exist in some general line of time” (Colebrook 42).

Time is a living and still moving eternity. It is an organic phenomenon and everything repeated in time is repeated in a new sense. Past contains the seeds of the present which, in turn, contain the seeds of the future. In Time and Free Will, Bergson uses the analogy of a “musical phrase which is constantly altered in its totality by the addition of some new note” (106) since “each new development alters the nature, the appearance and, as it were, the rhythm of the whole”

He perceives as the sickness of all revolutionary movements which tend to break connection with the past to form a radically altered sensibility in the present.

To form a healthy consciousness in the present, and to ameliorate the present conditions of life we should not break our relation with the past, nor should we deny or ignore the past. On the contrary, we should have a strong sense of tradition to outrun the past.

Contrast with: scientific/clock/intellectual/mathematical/rational/linear time, composed of separable bits. Time is spatialised into distinct ‘before’ and ‘after’. Time ticks away.

For modernist authors, the concept of duree is crucial to their understanding of the self. Authors use these concepts of time/experience/ultimate truths to communicate deep emotions and psychological needs. We go through life with the shadows of our entire pasts trailing behind us. We don’t think about this normally. But every now and then our memory rises up to impact the present and we attain some kind of insight into our present situation.

Short stories often recount an experience in the present which is defined by a character’s entire past/memory. At the end of the story, all of this comes together and the character achieves insight also known as an epiphany.

What does a Bergsonian concept of time mean on the page? The following are Modernist techniques which emulate Bergson’s duree concept of time:

- (narrated) monologue

- stream of consciousness

- fragmented consciousnesses and disintegrated persona — The self is considered ‘fragmented’ (there’s no one true self). This split is down to psychoanalyst ideas about a split between subconscious drives and conscious realisation. There’s no one, single ego. The self is fluid, and is always in a state of unfolding. A good word to use is ‘allotropic’ (D.H. Lawrence’s word), normally used in chemistry to describe something which can exist in two or more different forms. (Fragmentation of self is often conveyed on the page via fragmentation of syntax.)

- tunneling —Virginia Woolf’s word for how she burrowed into her characters’ backstories in order to show who they are in the present. Virginia Woolf defined her narrative method in her Diary: “my tunnelling process, by which I tell the past by instalments, as I have need of it.”

- interest in inner realities

- alienated figures

- defamiliarization — deliberately making the familiar look unfamiliar to encourage an audience to see their world through fresh eyes

- rhythm

- allusive language (suggesting something rather than being explicit)

- use of free verse (poetry that does not rhyme or have a regular rhythm)

- irresolution — open endings, aperture endings

- features of the setting function as correlatives for inner states and feelings of the characters who inhabit the space

- Modernists think of the inner world as like a labyrinth (or a tunnel, if they’re Virginia Woolf). Whether we’re talking about tunnels or labyrinths, we’re talking about getting to the heart of something with some effort, in a meandering way.

HAUNTOLOGY: THE PERSISTENCE OF A PRESENT PAST

Does Bergson’s concepts of duree and elan vital give you brain ache? You might prefer the concept of ‘hauntology’, a term preferred by philosophers of history, political scientists and also the creators of certain subgenres of electronic music (see the work of British music critic Simon Reynolds for use of ‘hauntological’ in the music world).

Jacque Derrida first used the word at a 1993 lecture. He was talking about the state of Marxist thought in the post-Communist era, but let’s not worry about that here. Since then, the word ‘hauntology’ has caught on somewhat, and it reminds me of Modernist concepts of time: The present moment doesn’t exist in isolation. Every present moment is affected by our history.

For Derrida himself, hauntology is a philosophy of history that upsets the easy progression of time by proposing that the present is simultaneously haunted by the past and the future.

Berkeley Art Museum’s exhibit notes for”Hauntology”

This was an important idea for Derrida, who was conveying the idea that the specter of Marxist utopianism haunts the present, capitalist society.

Also a part of hauntology:

- the identities of individuals are fluid and

- one person’s experience links to someone else’s

- both in the present moment

- and also across time.

MODERNIST SETTINGS

Modernist writers like to describe setting. They’re painting for us in words. Most modernist writers are excellent stylists. They know how to write a pretty sentence.

Gloomy atmospheres are common. This is probably not surprising. The idea that there is no such thing as ‘the real truth’ does tend to cast a gloomy cast on things.

MODERNISM AND CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

When critics write about Modernism, they don’t tend to talk about children’s literature very much, but the creators children’s stories were subject to the exact same cultural forces. What can be said of Modernist art in general also applies to children’s literature.

Extra features of Modernist children’s stories:

- Rejection of didacticism

- Children are provided with rich fantasy worlds, whose issues manifest in the real world as well.

- Stories don’t shy away from uncertainties and ambiguities of the real world, with the belief that children can cope with more difficult subject matter.

Modernism and children go very well together. Dream logic, fantasy, playfulness and imagination are all associated with children as well as with Modernism, allowing various (non-real) takes on the world.

As John Berger noted, children’s sense of time is also different from time as experienced by adults:

For Berger, a core difference between children and adults is how they experience time. “If we knew how long a night or a day was to a child,” he continued, “we might understand a great deal more about childhood.” For children, he argued, time tends to move more slowly than for adults, partly because adults tend to be much more aware of the “absurdity” of events that may befall them; this sense of “helplessness” and “anguish” in the face of such painful absurdity causes adults to experience time in a unique way.

For John Berger, the Time We Feel Most Deeply Can’t Be Kept on a Clock

Children’s naive sense of time is part of what makes the child point of view well-suited to Modernist takes on the world.

But in the world of academia, children’s literature has been given a hard time.

Them: “That children’s story is too simplistic for us to consider it an example of Modernism.”

Also them: “That story is too complex and is therefore not really for children.”

MICROMODERNISM

Modernist works which came from New Zealand, Australia and surrounds have been called ‘micromodernism’ (by Tim Armstrong). Katherine Mansfield is a standout example.

The slight difference is to do with the sense of distance white people have, growing up so far away from the imaginative ‘home land’, which back then, was England.

FURTHER READING

Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, Volume 32, Number 4, Winter 2007, Special Issue: Children’s Literature and Modernism.

Strange Likeness: Description in the Modernist Novel

In this interview, I talk with Dora Zhang, associate professor of English and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley, about her book Strange Likeness: Description in the Modernist Novel, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2020. While description has been “near universally devalued” in literary thinking, and particularly in Modernism, Zhang argues that descriptive practices were in fact a crucial site of attention and experimentation for a number of early modernist writers. She focuses on the works of Virginia Woolf, Henry James, and Marcel Proust to investigate how modernist descriptive techniques shift from a transcription of visuals to a translation and revelation of relations—social, formal, and experiential—between disparate phenomena. These writers maintained realism’s descriptive intentions to empirically document the world but expanded these commitments in new ways to render immaterial phenomena into language. In doing so, Zhang carries us beyond the classic dichotomies between narration and description and definition and description in order to rethink description and its place in the novel and, more broadly, literature.

New Books Network

Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design

In the world of interior design, mid-century Modernism has left an indelible mark still seen and felt today in countless open-concept floor plans and spare, geometric furnishings. Yet despite our continued fascination, we rarely consider how this iconic design sensibility was marketed to the diverse audiences of its era. Examining advice manuals, advertisements in Life and Ebony, furniture, art, and more, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design (Princeton UP, 2021) offers a powerful new look at how codes of race, gender, and identity influenced—and were influenced by—Modern design and shaped its presentation to consumers.

Taking us to the booming suburban landscape of postwar America, Kristina Wilson demonstrates that the ideals defined by popular Modernist furnishings were far from neutral or race-blind. Advertisers offered this aesthetic to White audiences as a solution for keeping dirt and outsiders at bay, an approach that reinforced middle-class White privilege. By contrast, media arenas such as Ebony magazine presented African American readers with an image of Modernism as a style of comfort, security, and social confidence. Wilson shows how etiquette and home decorating manuals served to control women by associating them with the domestic sphere, and she considers how furniture by George Nelson and Charles and Ray Eames, as well as smaller-scale decorative accessories, empowered some users, even while constraining others.

A striking counter-narrative to conventional histories of design, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body unveils fresh perspectives on one of the most distinctive movements in American visual culture.

interview at New Books Network

Before Modernism: Inventing American Lyric

Before Modernism: Inventing American Lyric (Princeton UP, 2023) examines how Black poetics, in antagonism with White poetics in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, produced the conditions for the invention of modern American poetry. Through inspired readings of the poetry of Phillis Wheatley Peters, George Moses Horton, Ann Plato, James Monroe Whitfield, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper—as well as the poetry of neglected but once popular White poets William Cullen Bryant and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—Virginia Jackson demonstrates how Black poets inspired the direction that American poetics has taken for the past two centuries. As an idea of poetry based on genres of poems such as ballads, elegies, odes, hymns, drinking songs, and epistles gave way to an idea of poetry based on genres of people—Black, White, male, female, Indigenous—almost all poetry became lyric poetry. Jackson discusses the important role played by Frederick Douglass as an influential editor and publisher of Black poetry, and traces the twisted paths leading to our current understanding of lyric, along the way presenting not only a new history but a new theory of American poetry.

A major reassessment of the origins and development of American poetics, Before Modernism argues against a literary critical narrative that links American modernism directly to British or European Romanticism, emphasizing instead the many ways in which early Black poets intervened by inventing what Wheatley called “the deep design” of American lyric.

New Books Network

The Forces of Form in German Modernism

The late 19th and early 20th centuries in Europe were times of intense technological, social and political change and transformation, and so it’s no surprise that much of the art and literature of this period was equal in its innovative intensity, attempting to make sense of times that were radically out of joint. Traditional scholarship on this period has focused on the alienation and disassociation that can be experienced when trying to keep up with the frenetic pace of modern life. But is this what the artists and writers of the day were trying to communicate to their audience?

Without discounting the alienating effects of modernity, Malika Maskarinec has stepped in with a fascinating monograph on the period, The Forces of Form in German Modernism (Northwestern UP, 2018), which challenges and complicates this reading, drawing our attention to other themes present in the work of the period. Turning to various archival sources to see what the artists and their peers were interested in, Maskarinec finds a collection of figures reflecting on questions of the forces and forms that hold bodies together against the weight of gravity. In this intellectual milieu, buildings and statues capacity to hold themselves up can be part of profound aesthetic experience, abstract shapes maintaining their position on a page can stir feelings of empathy, and even simple everyday activities such as laying down, standing up and walking around are activities of profound existential importance. Touching on figures such as Schopenhauer, Rodin, Simmel, Klee and Kafka, Maskarinec’s book is overflowing with insights that will help students and scholars of the period revisit these works with fresh eyes, and like the artists and writers discussed, she will prove an excellent interlocutor for all those interested in what it means to be human.

New Books Network

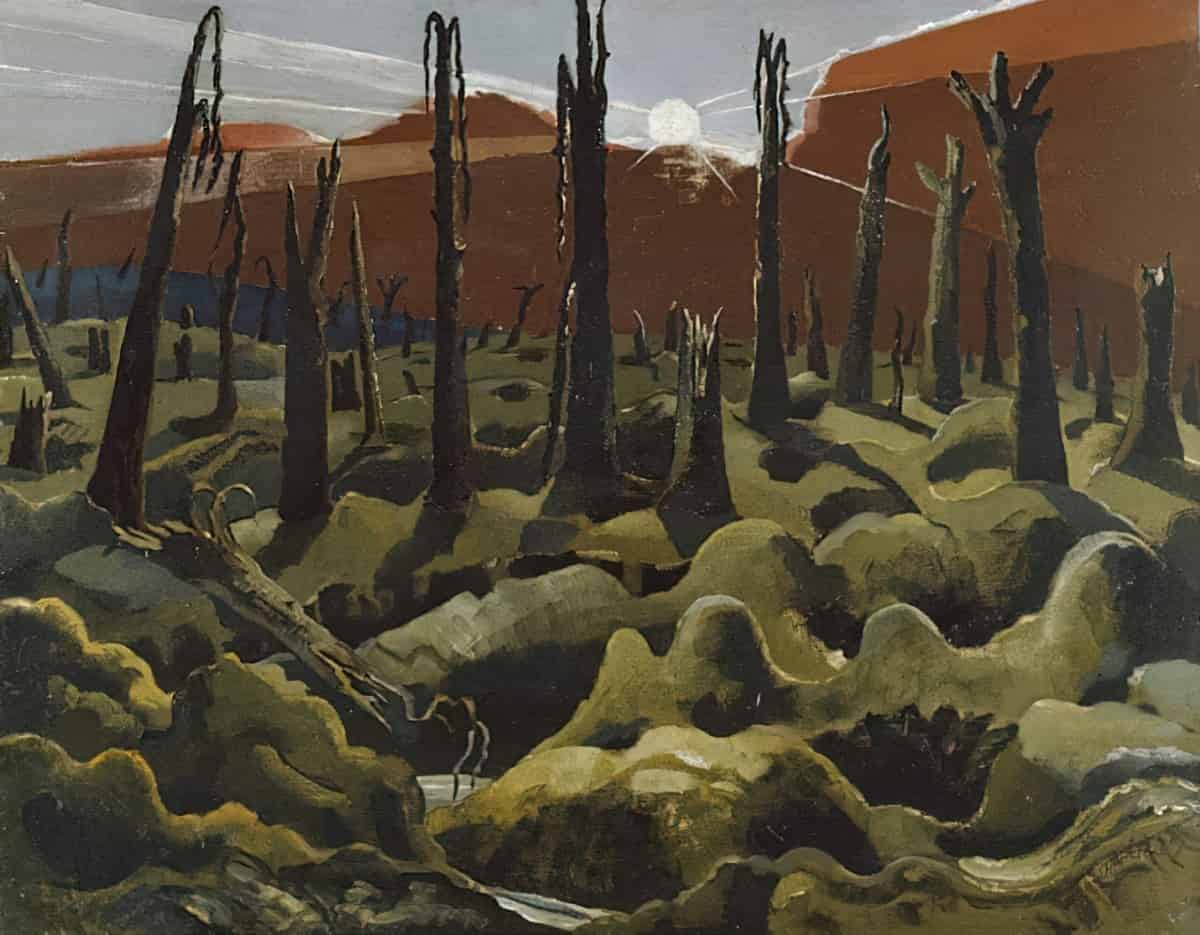

Header painting: 1918 We Are Making a New World, Paul Nash, UK