Literary impressionism centres on the following questions: Who am I and What is it all about? In impressionist literary works, themes are difficult to pin down because the reader is expected to bring a lot to the table. This is true of lyrical stories in general.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LITERARY IMPRESSIONISM

Charles Baudelaire’s poetry inspired the symbolist movement in literature, which communicated through symbolist subjects. The goal of symbolism was to convey the essence of a subject rather than reproducing it.

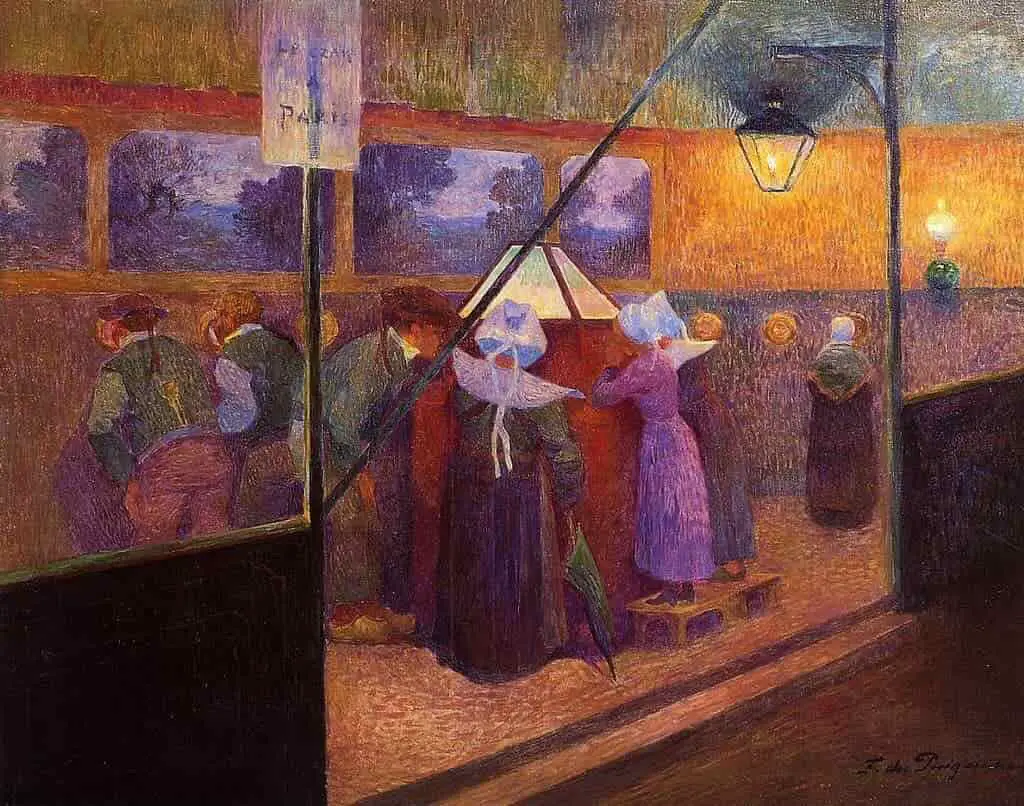

Impressionism produced new forms in literature: the prose poem and the psychological sketch. Emphasis is on how things appear — on the sense of sight in particular.

The modern lyrical short story is not a genre in its own right, but a natural consequence of literary Impressionism. The best examples of Impressionism can be found in short stories. Because of their length, short stories are better able to ‘paint an Impressionist picture’, so the Impressionist bits are more obvious.

GENERAL FEATURES OF IMPRESSIONIST LITERARY WORKS

Characters and settings are suggested rather than defined.

Impressionist works are all about the transient nature of reality and the complexity of truth.

Better a half truth, beautifully whispered, than a whole solemnly shouted.

Katherine Mansfield

For more on the half-truths of literature see: We All Half Know Things.

They share this in common with many historians today:

Historians: All histories are fiction. Objective truth is illusory. Every narrative is a subjective product of its author and context, with no tangible bearing upon reality.

Historians watching any film remotely connected to their field: Well that never fuckin’ happened.

Maxwell T Paule (@VeneficusIpse) February 27, 2020

A few strokes capture the mood of the characters and the minute ‘objective’ details (which are actually subjective).

The personal impression of any experience is of greater importance to the Impressionist than any accurate description of reality.

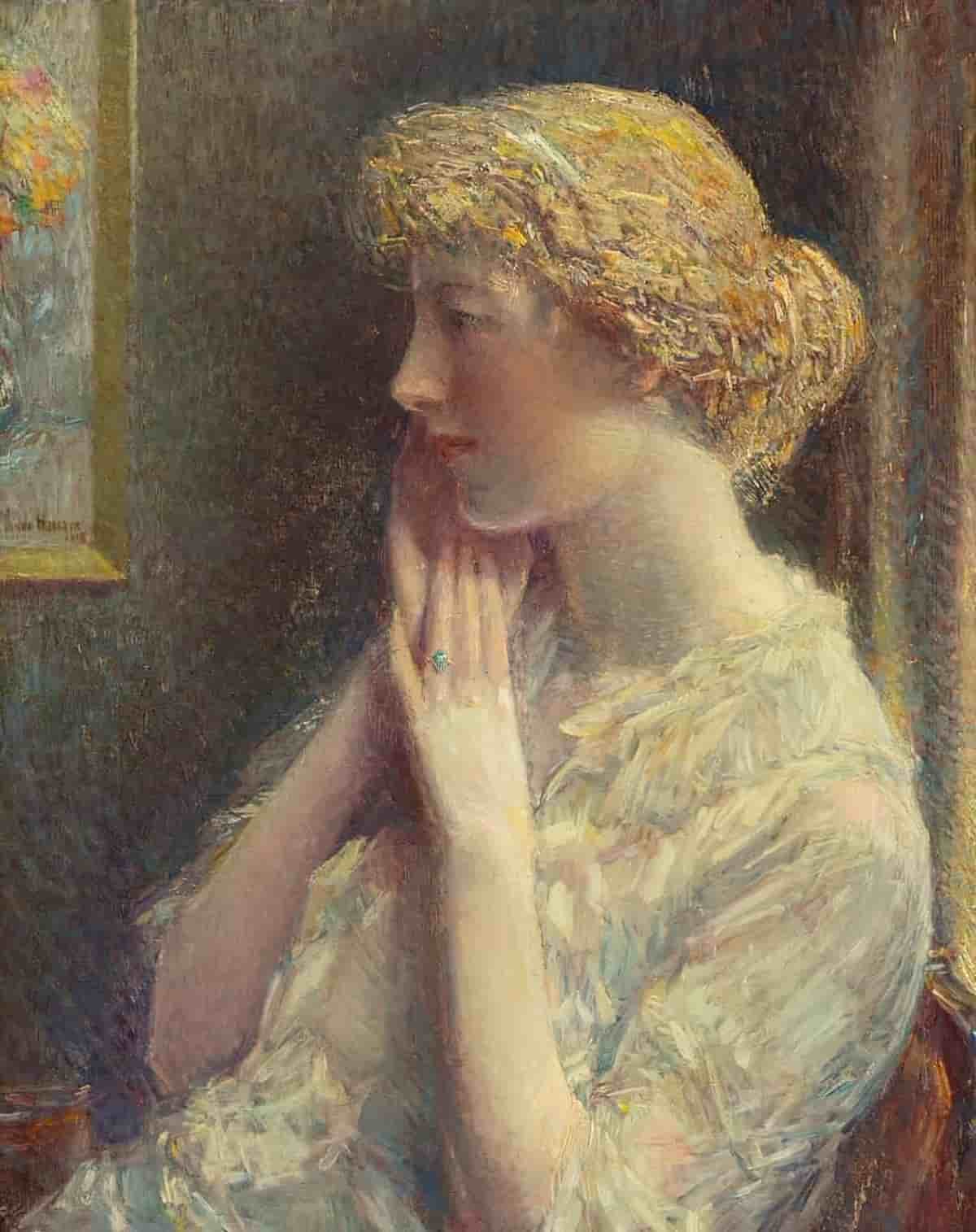

Like an Impressionist painter she worked to convey the light and the shade, the overall impression or mood; details were altered, outlines blurred and places, people or occasions merged into a composite picture […] people were shaped and manipulated to fit the impression she wished to create.

Gillian Boddy of Katherine Mansfield, 1988

NARRATION

In Impressionism, a (homodiegetic) narrator tells a story which is fragmentary, seemingly objective, dramatic and indirectly suggestive.

Since Impressionist stories are all about indirectness, some kind of limiting point of view is best. The narrator has limited powers — everything is filtered via a focalising character. Two preferred limiting points of view (in third person) are narrated monologue and free indirect speech (also called free indirect discourse).

It is up to readers to piece together fragments and come to our own conclusion about who this person is and what’s happening in the story. The fictional character can’t see the full picture because they are stuck within the setting.

The narrative will emphasise the sensory and inner world of a character.

THE PARALLAX TECHNIQUE

Parallactic narration can be achieved when reality is described differently from multiple viewpoints. None of these narrators is omniscient — none of them has seen or understood the entire ‘story’.

‘Foolish child. All you could tell was that he thought he was telling the truth. The world isn’t always as people see it.’

Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites

Impressionist stories show us that characters (and therefore people) are conditioned by their environment and prone to distortion and misinterpretation. Unreliable, in other words. But this is not because they’re being deliberately deceitful. They are unreliable because they don’t quite understand themselves or their relationship to their world. This is how the character genuinely perceives reality. Remember the central questions of Impressionism: Who am I? How am I connected to my world?

For more on the parallactic technique in storytelling, see this post.

DETAIL

Detail will look like ‘a flash perception of an outstanding aspect of the object’. In film, Terence Malick’s Tree of Life makes for an excellent visual example of how Impressionism looks in literature.

THE SUM WILL BE GREATER THAN THE PARTS

On their own, all of these details mean little. But they work together to create a symbol web, and only make sense once the reader has seen the whole story and stood back. Impressionist artwork works in the same way — stand too close and focus on any single brush stroke and the detail will seem random.

THE LANGUAGE OF IMPRESSIONISM

The prose is unabashedly purple. Early Impressionist writers were attempting to express everything to the last extremity and fix the last fine shade of mood and feeling. Subtlety is key.

But it wasn’t poetry. They were more interested in prose than in poetry. Prose was seen as a more inconclusive medium — the writer isn’t hemmed in by requirements of rhyme and metre. Prose is better to express feeling, reflections, comparisons.

But this prose was heavily influenced by poetry and is clearly aesthetically designed.

STORY STRUCTURE OF AN IMPRESSIONIST LITERARY WORK

Character and plot are enveloped in atmosphere. Every story function is conveyed indirectly.

Impressionist stories don’t have an elaborate finishing touch. This is to maintain across the entire story a narrator’s subjective, fragmentary impression of the world.

The main character really wants to know the ‘truth’ of human consciousness but if they realise anything long term, it’s that there is no ‘truth’ — only perceived fragments of highly ambiguous sensory stimuli.

At the Anagnorisis phase, the Impressionist main character is kept in the state where they want to learn the meaning of their experience but at the same time they’re unable to do so. Or they have a brief moment of clarity, but that is soon forgotten. We might call this anagnorisis illusory or phantasmagoric. An excellent example of this is “The Garden Party” by Katherine Mansfield. A much more recent short story example: “In-flight Entertainment” by Helen Simpson.

CHARACTERISATION

In Realism natural phenomena are generally described as they are commonly understood to be. But in Literary Impressionism the author simulates a sensory experience. This is presented with little additional information. Characters are not great noticers. They perceive their settings in momentary, fragmented pieces.

Because they know little about the bigger picture, they’re unreliable narrators. But remember, that’s not because they’re trying to deceive anyone — they really don’t know themselves very well. They’ve been shaped by their environment to the point where they can’t see that. They are unreliable because they are unable to sustain any realistic conception of themselves.

They tend to resort to fantasies and reality is distorted by illusion. Their false and incomplete data can contribute to a feeling of isolation in the world.

An Impressionist character generally faces a cognitive rather than a moral dilemma, and establishing the character’s background or history is, therefore, of little importance.

DETAILS

Although both Naturalist and Impressionist writers may pay a great deal of attention to details there is a difference in their use of it. Where the Naturalist tends to be comprehensive and complete, the Impressionist is highly selective. Where the Naturalist tends to give equal emphasis to a large number of details, Mansfield singles out the first detail that catches the narrator’s eye, the main impression on the particular occasion, and has the detail completely dominate the scene.

Julia van Gunsteren, Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

Note that there’s a whole cluster of international art movements and definitions are often at great variance: impressionism, post-impressionism, realism, symbolism, modernism, symbolism, naturalism, imagism, Dadaism, surrealism, expressionism, futurism and so on).

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

- Julia Van Gunsteren’s book Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

- Beverly Jean Gibbs “Impressionism as a Literary Movement”

Header painting is Claude Monet’s Impression Sunrise 1872 — the painting which led to the first insult which led to the reclamation of the word ‘impressionism’ as an art movement.