Repetition is sometimes accidental when it pops up in first drafts, but deliberate repetition is important when telling a story. The trick is knowing when to repeat yourself, and why you’re doing it.

LISTS

Some writers are famous for their lists. Lists can feel repetitive, which is why I include them here. Katherine Mansfield is famous for piling very similar adjectives on top of each other, She did this to contrast patterns of images, generating a thematic layer of meaning.

20th century authors Kenneth Grahame and E.B. White are two standout examples from the world of children’s literature:

Meantime Toad packed the lockers still tighter with necessaries, and hung nosebags, nets of onions, bundles of hay, and baskets from the bottom of the cart.

Little sleeping bunks–a little table that folded up against the wall–a cooking-stove, lockers, bookshelves, a bird-cage with a bird in it; and pots, pans, jugs and kettles of every size and variety.

The Wind In The Willows, Kenneth Grahame

The rat had no morals, no conscience, no scruples, no consideration, no decency, no milk of rodent kindness, no compunctions, no higher feeling, no friendliness, no anything.

E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web

Lists are a marker of stream of consciousness narration, as exemplifed by Virginia Woolf:

In people’s eyes, in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Although lists may feel exhaustive, they must still be carefully curated:

Too much explicitness is a bad thing. There is no need to describe everything that goes on at the table where the family is sitting. There are certain things you should pick out. You should find ways of describing, say a street like this — just to get it in a sentence or two. You should also have a much better ear for ordinary speech than is common.

V.S. Pritchett

CATALOGING

Cataloguing refers to creating long lists for poetic or rhetorical effect. The technique is common in epic literature, where conventionally the poet would devise long lists of famous princes, aristocrats, warriors, and mythic heroes to be lined up in battle and slaughtered.

The technique is also common in the practice of giving illustrious genealogies (“and so-and-so begat so-and-so,” or “x, son of y, son of z” etc.) for famous individuals. An example in American literature is Whitman’s multi-page catalog of American types in section 15 of “Song of Myself.”

The pure contralto sings in the organ loft,

The carpenter dresses his plank, the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp,

The married and unmarried children ride home to their Thanksgiving dinner,

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm,

The mate stands braced in the whale-boat, lance and harpoon are ready,

The duck-shooter walks by silent and cautious stretches,The deacons are ordained with crossed hands at the altar,

The spinning-girl retreats and advances to the hum of the big wheel,The farmer stops by the bars as he walks on a First-day loaf and looks at the oats and rye,The lunatic is carried at last to the asylum a confirmed case…. [etc.]

One of the more humorous examples of cataloging appears in the Welsh Mabinogion. In one tale, “Culhwch and Olwen,” the protagonist invokes in an oath all the names of King Arthur’s companion-warriors, giving lists of their unusual attributes or abilities running to six pages.

Literary Terms and Definitions

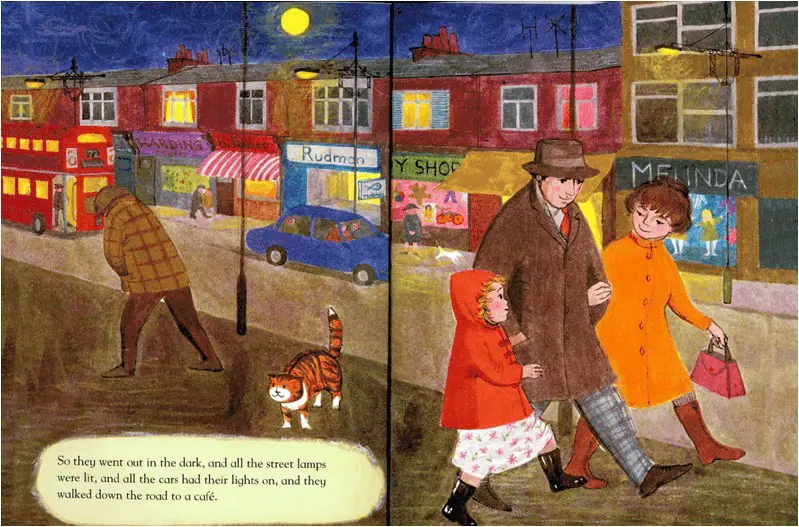

The first part of Goodnight Moon (1947) by Margaret Wise Brown is literally just a list of things in a bedroom.

E.B. White was big on cutting out all unnecessary words, but this didn’t apply to lengthy lists. Charlotte’s Web is well-known for its lists.

CATALOGUING FOOD

Food is really important in children’s literature (even if by ‘children’s literature’ we mean ‘collegiate’.

“A fair is a rat’s paradise. Everybody spills food at a fair. A rat can creep out late at night and have a feast. In the horse barn you will find oats that the trotters and pacers have spilled. In the trampled grass of the infield you will find old discarded lunch boxes containing the foul remains of peanut butter sandwiches, hard-boiled eggs, cracker crumbs, bits of doughnuts, and particles of cheese. In the hard-packed dirt of the midway, after the glaring lights are out and the people have gone home to bed, you will find a veritable treasure of popcorn fragments, frozen custard dribblings, candied apples abandoned by tired children, sugar fluff crystals, salted almonds, popsicles,partially gnawed ice cream cones,and the wooden sticks of lollypops. Everywhere is loot for a rat–in tents, in booths, in hay lofts–why, a fair has enough disgusting leftover food to satisfy a whole army of rats.”

Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White

In The Wind In The Willows, Kenneth Grahame does something interesting with punctuation: he omits the spaces between words to show how very overwhelmed the humble-living Mole is at hearing the contents of Ratty’s picnic:

“There’s cold chicken inside it,” replied the Rat briefly; “coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscresssandwichespottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater–“

The Wind In The Willows, Kenneth Grahame

“O stop, stop,” cried the Mole in ecstasies: “This is too much!”

In “I Live On Your Visits” by Dorothy Parker, a clingy mother tells her son she doesn’t have enough to eat, but will happily share her boiled egg. When the son goes to her refrigerator, he opens it to find:

There were a cardboard box of eggs, a packet of butter, a cluster of glossy French rolls, three artichokes, two avocados, a plate of tomatoes, a bowl of shelled peas, a grapefruit, a tin of vegetable juices, a glass of red caviar, a cream cheese, an assortment of sliced Italian sausages, and a plump little roasted Cornish Rock hen.

I Live On Your Visits

In this particular story, humour derives from the mother’s sense of lack and the observed reality of her well-stocked fridge.

DRAMATISED ROUTINE

How to Make the Best Use of “Routine” Events in Your Fiction by Peter Selgin at Jane Friedman’s blog.

Selgin makes the point that when writers describe a routine in fiction, the reader remains interested because they expect the routine to be shattered at some point. There is a sweet spot regarding how long the ‘description of the routine’ can go on for.

This has been studied in children’s books, and Maria Nikolajeva calls the routine part of the story the ‘iterative’ phase, which is subequently punctured by a switch to the ‘iterative’.

This switch is especially noticeable in older children’s books. New ones often plunge readers straight into the action.

MELODRAMA

When Toad of The Wind In The Willows is convicted of bad driving and ‘cheek’, he is sent down into the dungeons for 20 years. Kenneth Grahame lets the reader follow Toad on his melodramatic descent. He does this by making use of a list, which is basically one very long sentence. (I believe that pun is fully intended.)

The brutal minions of the law fell upon the hapless Toad; loaded him with chains, and dragged him from the court house, shrieking, praying, protesting; across the market-place, where the playful populace, always as severe upon detected crime as they are sympathetic and helpful when one is merely ‘wanted’, assailed him with jeers, carrots, and popular catch-words; past hooting school children, their innocent faces lit up with the pleasure they ever desire from the sight of a gentleman in difficulties; across the hollow-sounding drawbridge, below the spiky porcullis, under the frowning archway of the grim old castle, whose ancient towers soared high overhead; past guardrooms full of grinning soldiery off duty, past sentries who coughed in a horrid sarcastic way, because that is as much as a sentry on his post dare do to show his contempt and abhorrence of crime; up time-worn winding stairs, past men-at-arms in casquet and corselet of steel, darting threatening looks through their vizards; across courtyards, where mastiffs strained at their leash and pawed the air to get at him; past ancient warders, their halberds leant against the wall, dozing over a pasty and flagon of brown ale; on and on, past the rack-chamber and the thumbscrew-room, past the turning that led to the private scaffold, till they reached the door of the grimmest dungeon that lay in the heart of the innermost keep. There at last they paused, where an ancient gaoler sat fingering a bunch of mighty keys.

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind In The Willows, “Mr Toad”.

REPETITION AND THE GOTHIC TRADITION

Reiteration is the modern form of haunting; reiteration of narrative manoeuvres and motifs, unholy reanimation of the deadness of the past that has the power to make something new.

Modern Gothic: A Reader, introduction by Sage and Lloyd Smith

This paragraph from a classic Edwardian work was basically redone for a young audience decades later in the Halloween favourite In A Dark Dark Room, which contains the following horror incantation:

In a dark, dark wood there was a dark, dark house.

In A Dark, Dark Room

And in that dark, dark house there was a dark, dark room.

And in that dark, dark room there was a dark, dark closet.

And in that dark, dark closet there was a dark, dark shelf.

And in that dark, dark shelf there was a dark, dark box.

And in that dark, dark box there was a

GHOST!!!

Both passages make use of lists. Kenneth Grahame’s achieves melodrama owing to the lack of full-stops. We imagine a langurous character complaining at length about his terrible predicament.

INDUCING A HYPNOGOGIC STATE

REPETITIVE NARRATIVE

A narrative can … tell several times, with or without variations, an event that happened only once, as in a statment of this kind: “Yesterday I went to bed early, yesterday I went to bed early, yesterday I tried to go to sleep well before dark,” etc. This last hypothesis may seem a priori to be a gratuitous one, or even to exhibit a slight trace of senility. One should remember, however, that most texts by Alain Robbe-Grillet, among others, are founded on the repetitive potential of the narrative: the recurrent episode of the killing of the centiped, in La Jalousie, would be ample proof of this. I shall call repetitive narrative this type of narration, in which the story-repetitions exceed in number the repetitions of events.

Narrative Dynamics: Essays on Time, Plot, Closure, and Frames, “Order, Duration and Frequency”.

REPEATED KEY WORDS AND ARC PHRASES IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

‘Key words’ in storytelling is a slightly wider-ranging way to describe the motif.

We all know people in real life who […] use a series of jingles and tags and repetitive gestures to maintain a certain kind of performance.

James Wood, How Fiction Works

At TV Tropes, you’ll find an entry for ‘Arc Words‘: Words or a phrase that appears throughout the story as an Arc or as a Motif.

Likewise, the arc phrase is employed by many authors of middle grade fiction.

Examples Of Key Words In Middle Grade Fiction

In Once by Morris Gleitzman the arc phrase word involves the word Once, which was introduced — most obviously — as the title.

Everybody deserves to have something good in their life. At least once.

Barney said that everybody deserves to have something good in their life at least once. I have. More than once.

Related to arc phrases are ‘catch phrases’.

The hero of Once is in a dire situation — he is a Polish kid in the Nazi era, dodging murder at every turn. It would be easy for this story to turn into a sob story, so Gleitzman has him use the phrase, “You know how…” whenever he’s telling the reader something terrible about his life. This is more of a character tic than a motif.

The first example occurs at the third sentence of the book, and these situations he describes only get more and more dire:

You know how when a nun serves you very hot soup from a big metal pot and she makes you lean in close so she doesn’t drip and the steam from the pot makes your glasses go all misty and you can’t wipe them because you’re holding your dinner bowl and the fog doesn’t clear even when you pray to God, Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Pope and Adolf Hitler?

That’s happening to me.

Millions by Frank Cottrell Boyce is a middle grade novel which was written concurrently with the screenplay. My point is that the book was written by an experienced writer of screenplays. Naturally Cottrell Boyce made use of all he knew about screenplays when writing the middle grade novel.

In Millions, the first person storyteller narrator repeats the phrase, “To get X about it…“

Judy Moody (series written by Megan McDonald) has a catch phrase — I don’t know if it’s a regional dialect but I’ve never heard it before: “Rare!” My seven-year-old started using this word only after reading it in Judy Moody, though she did use it in the general way rather than in the Judy Moody way, as an exclamation.

Joan Aiken’s raven, Mortimer, squawks “Nevermore!” in reference to the classic poem, which is funny because the stories are slapstick humorous whereas the poem is gothic horror. Apart from making squawk type sounds this is the only word he knows. Aiken adroitly contrives a surprising number of occasions in which he can use it.

Unintentional Pop Culture Spoofing

Chances are that looking back on your childhood experience of reading Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series, you remember ‘lashings of‘ in reference to the picnics — lashings of cream, lashings of butter, lashings of ginger beer. If you happen to re-read those books the word ‘lashings’ doesn’t actually appear all that often. But for some reason it stuck! Helped along by Comic Strip Presents… Five Go Mad In Dorset parody. ‘Lashings’ became part of pop culture mostly as a derisive comment on Blyton’s unimaginative prose, I suspect (she could pump these out one per week). I’m sure this spoof does the popularity of the series no harm.

If Enid Blyton had belonged to a critique group, or had she been more of a stylist, her (over)use of the word ‘lashings’ may have been edited out. But as Blyton’s ‘lashings’ demonstrates, even unintentional overuse of a word can become part of its enduring popularity.

These repeated phrases are also called ‘refrains’. See another useful list of them here.

‘Key words’ in storytelling is a slightly wider-ranging way to describe the motif.

We all know people in real life who […] use a series of jingles and tags and repetitive gestures to maintain a certain kind of performance.

James Wood, How Fiction Works

At TV Tropes, you’ll find an entry for ‘Arc Words‘: Words or a phrase that appears throughout the story as an Arc or as a Motif.

Likewise, the arc phrase is employed by many authors of middle grade fiction.

Examples Of Key Words In Middle Grade Fiction

In Once by Morris Gleitzman the arc phrase word involves the word Once, which was introduced — most obviously — as the title.

Everybody deserves to have something good in their life. At least once.

Barney said that everybody deserves to have something good in their life at least once. I have. More than once.

Related to arc phrases are ‘catch phrases’.

The hero of Once is in a dire situation — he is a Polish kid in the Nazi era, dodging murder at every turn. It would be easy for this story to turn into a sob story, so Gleitzman has him use the phrase, “You know how…” whenever he’s telling the reader something terrible about his life. This is more of a character tic than a motif.

The first example occurs at the third sentence of the book, and these situations he describes only get more and more dire:

You know how when a nun serves you very hot soup from a big metal pot and she makes you lean in close so she doesn’t drip and the steam from the pot makes your glasses go all misty and you can’t wipe them because you’re holding your dinner bowl and the fog doesn’t clear even when you pray to God, Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Pope and Adolf Hitler?

That’s happening to me.

Millions by Frank Cottrell Boyce is a middle grade novel which was written concurrently with the screenplay. My point is that the book was written by an experienced writer of screenplays. Naturally Cottrell Boyce made use of all he knew about screenplays when writing the middle grade novel.

In Millions, the first person storyteller narrator repeats the phrase, “To get X about it…“

Judy Moody (series written by Megan McDonald) has a catch phrase — I don’t know if it’s a regional dialect but I’ve never heard it before: “Rare!” My seven-year-old started using this word only after reading it in Judy Moody, though she did use it in the general way rather than in the Judy Moody way, as an exclamation.

Joan Aiken’s raven, Mortimer, squawks “Nevermore!” in reference to the classic poem, which is funny because the stories are slapstick humorous whereas the poem is gothic horror. Apart from making squawk type sounds this is the only word he knows. Aiken adroitly contrives a surprising number of occasions in which he can use it.

Unintentional Pop Culture Spoofing

Chances are that looking back on your childhood experience of reading Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series, you remember ‘lashings of‘ in reference to the picnics — lashings of cream, lashings of butter, lashings of ginger beer. If you happen to re-read those books the word ‘lashings’ doesn’t actually appear all that often. But for some reason it stuck! Helped along by Comic Strip Presents… Five Go Mad In Dorset parody. ‘Lashings’ became part of pop culture mostly as a derisive comment on Blyton’s unimaginative prose, I suspect (she could pump these out one per week). I’m sure this spoof does the popularity of the series no harm.

If Enid Blyton had belonged to a critique group, or had she been more of a stylist, her (over)use of the word ‘lashings’ may have been edited out. But as Blyton’s ‘lashings’ demonstrates, even unintentional overuse of a word can become part of its enduring popularity.

These repeated phrases are also called ‘refrains’. See another useful list of them here.

RHETORICAL DEVICES INVOLVING REPETITION

HOMOIOTELEUTON

Homoioteleuton is the repetition of words with similar endings.

- I was running, singing, and dancing all at once.

- The plane made aerial radial shapes as if around a sundial.

- She much prefers admiration and adoration over rejection.

Epanados

The repetition of words from earlier in a phrase or sentence in the reverse order.

In A Portrait of the Artist of the Young Man, James Joyce makes use of this device to suggest the psychological drive in the character (from outwardness to inwardness).

Antimetabole

The repetition of words in successive clauses, but in transposed order; for example, “I know what I like, and I like what I know”.