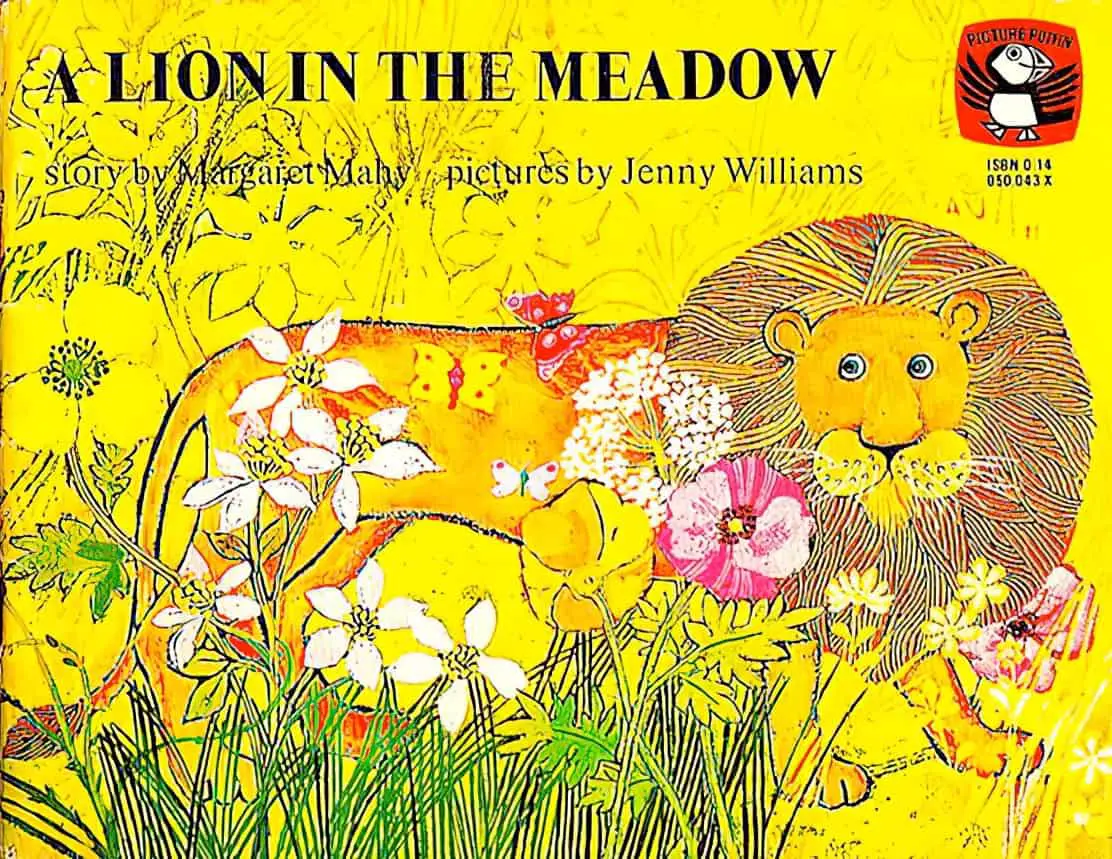

A Lion In The Meadow, written by Margaret Mary and illustrated by Jenny Williams (twice), is a picture book first published in 1969. In some ways this picture book feels dated, but in other ways not at all. This story is interesting as an example of an ironically funny anagnorisis.

I used to get quite a lot of my work published in a New Zealand magazine called The School Journal. There happened to be a printing exhibition over in New York, and New Zealand sent some examples of fine printing, including The School Journal. A woman called Helen Hoke Watts — the wife of the man who ran the publishing company Franklin Watts — saw a copy and read one of my stories, “A Lion in the Meadow,” which she thought would make a good picture book.

interview with Margaret Mahy at The Horn Book. This picture book started out as a story for the journal that New Zealand children read after graduating from early readers.

THE PROTO SUPERHERO STORY

Child characters whose warnings are ignored by adults — even in the midst of clear and present danger — are stock fodder and perennial favourites in children’s stories.

The 1990s gave us the cartoon series Courage the Cowardly Dog, which uses this trope over and over, as part of the structure of every episode: Courage sees a baddie, but Muriel (who is short-sighted) and Eustace (who is unkind) never take him seriously. It’s therefore up to Courage to save the day — a take on the superhero story and the lone hero for a younger audience. Thus, these characters are proto-superhero characters in their own way.

Another example is Not Now, Bernard by Robert McKee, published in 1980. Bernard tells his mother there’s a monster in the garden and it’s going to eat him, but the adults turn a deaf ear. The monster eats Bernard up, every bit. The purple monster then takes Bernard’s place in the house, causing mayhem. The monster explains himself by saying ‘I’m a monster’. The mother responds as ever, ‘Not now, Bernard’. In this way, the child is depicted as a little monster in the house. The adult can’t tell the difference between a tiny tot and a beast.

This category of stories are as much about parenthood as they are about childhood, and so speak to a dual audience. This theme was explored by Ali Smith in her short story The Child — a story for adults — in which a woman finds a racist, sexist baby in her shopping trolley and is obliged to take him home because no one else will have him. She ends up leaving him in someone else’s cart — he’s so terrible.

As part of this Chicken Licken tradition, New Zealand gave us Margaret Mahy and Margaret Mahy gave us A Lion In The Meadow. This in turn was influenced by works such as Where The Wild Things Are, in which children see monsters which adults cannot. This book was Mahy’s personal first, and remains one of the most influential children’s books to have come out of my home country. In 2013, an image from the book appeared on a postage stamp.

STORY STRUCTURE OF A LION IN THE MEADOW

Although this isn’t a cumulative plot per se, Mahy makes use of cumulation in this story, with one scary thing leading to another scary thing.

SHORTCOMING

The story opens with an in medias res sort of statement which reminds me a lot of Margaret Wise Brown’s openings, seen for instance in The Sailor Dog, in which it is assumed we already know this boy. And the truth is, we probably do. The ONLY time we don’t know this boy is the very first time we read it, but picture books are read many, many times. Hence ‘the’ little boy, not ‘a’ little boy:

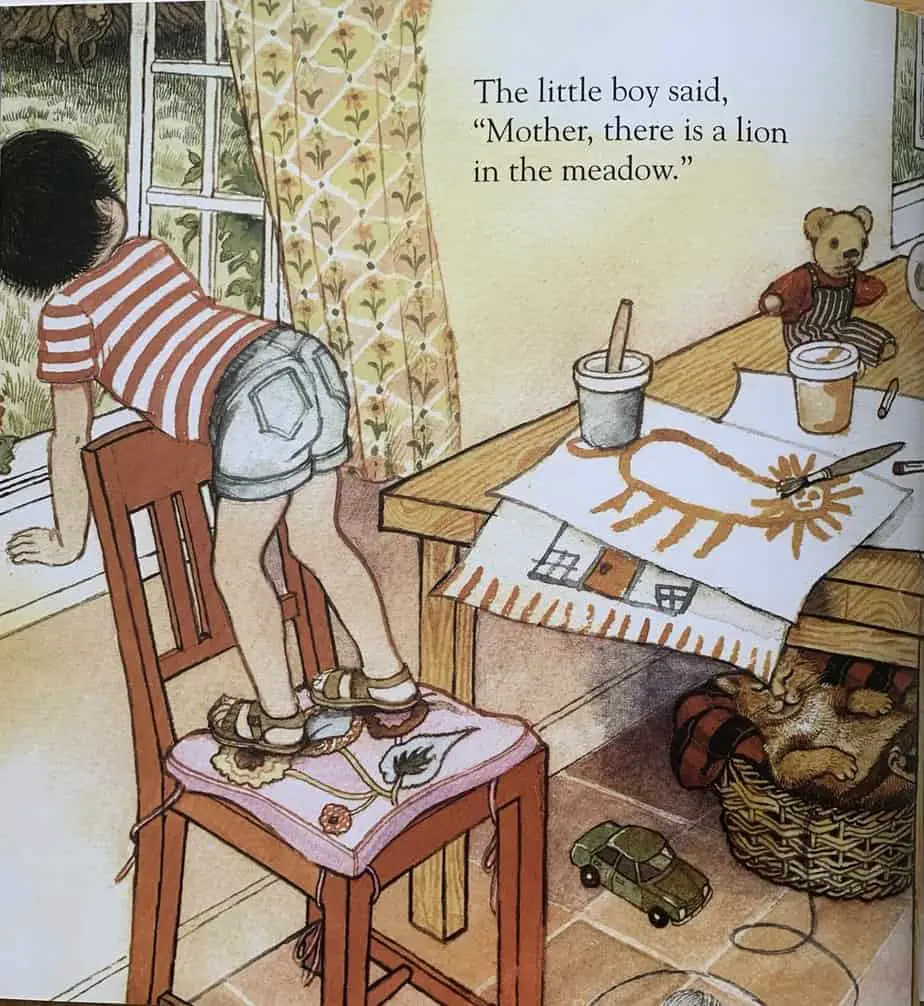

The little boy said,

“Mother, there is a lion in the meadow.”

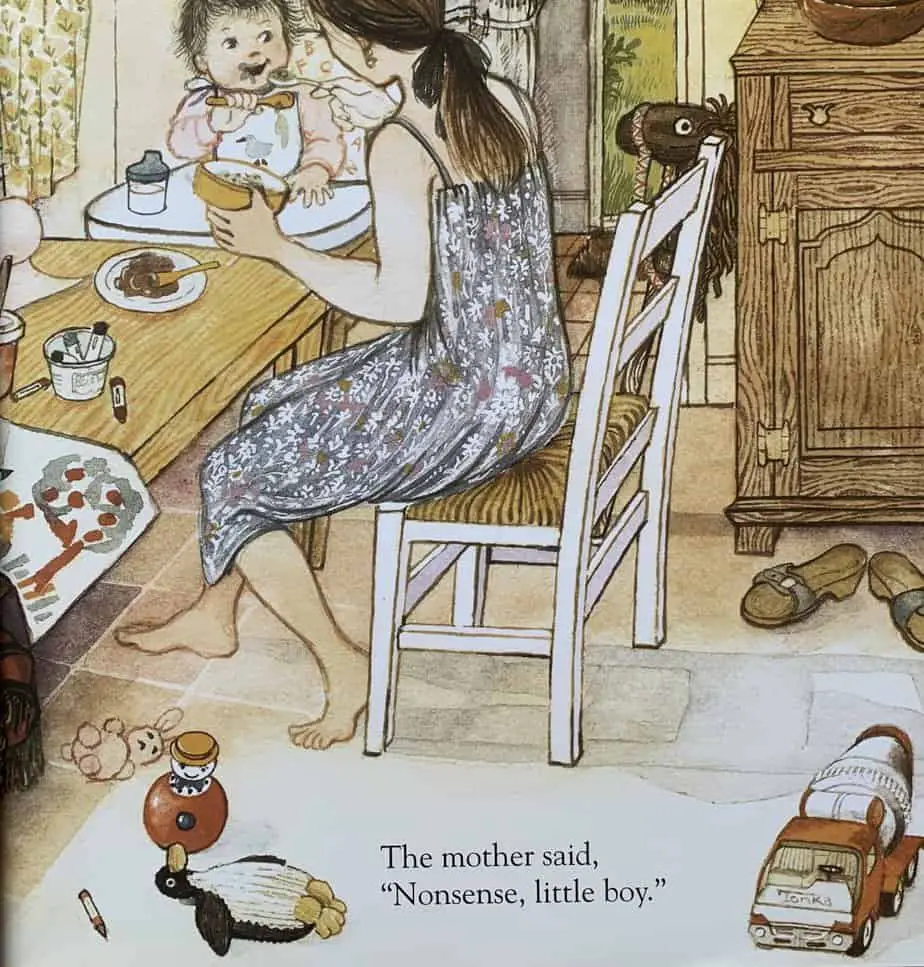

The mother said,

“Nonsense, little boy.”

The boy’s major shortcoming is that he is a child and adults don’t take him seriously.

DESIRE

One of our major desires as humans is to be taken seriously, and this applies equally to children. But this is more of a ‘psychological need’.

The little boy wants to play, and he wants to engage his mother somehow. If he can get his mother to believe in his stories, the stories seem more real, and therefore more fun.

OPPONENT

Mother, who doesn’t believe his stories. That means she can’t make his play better. But then she does make his imaginary play better. She’s now an ally.

The opponent is a false opponent, because it turns out this lion only eats apples.

The ‘real’ imaginary opponent remains the dragon, who the boy and the lion decide to avoid.

A big, generally bad opponent in a story is very useful, alongside the more familiar ones. They are typically dragons, wolves, demons, witches, ogres. We never know much about them other than their badness.

PLAN

The boy’s plan is not that interesting — he keeps repeating himself to his mother. He insists there’s a lion in the meadow.

The mother’s plan is interesting. She adds to the story by using a matchbox and a dragon. (Let’s hope there were no matches in it, or we really are in for some sort of ‘fire-breathing’ creature, with all that long grass.

But the mother’s plan has an unexpected outcome: rather than ‘fixing’ the problem of the lion, the little boy incorporates the dragon into his imaginary play.

BIG STRUGGLE

The illustration of the pink dragon breathing fire is the big struggle scene. The boy is never in direct big struggle with this dragon (because the dragon is imaginary). He runs inside to his mother, who is holding a saucepan.

ANAGNORISIS

When the little boy sits on his mother’s lap and the lion says “That is how it is. Some stories are true, and some aren’t,” this is probably coming out of the mother’s mouth (really), or perhaps it’s understood by the boy inside his head. In any case, that is the anagnorisis.

But coming out of the mouth of an imaginary creature, the ‘revelation’ is ironic. The little boy understands some things are true and some things aren’t, but he hasn’t got it straight which is which.

NEW SITUATION

The little boy now avoids the meadow where he believes the dragon resides, and the mother decides never to tell another story again.

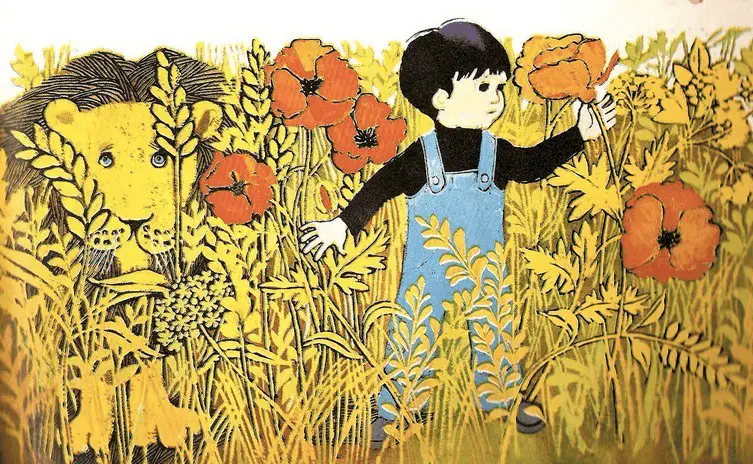

The original 1960s cover illustration has since been updated, but Jenny Williams’ new style doesn’t impress me as much.

The illustrations of the first version of A Lion In The meadow remind me of Judith Kerr’s very much, with even more of a late 60s, early 70s style, which incorporates folk art, and prefers side-on views rather than a fully three dimensional look. There are even shades of The Tiger Who Came To Tea in this story. Kerr’s book came out a year earlier than A Lion In The Meadow, which indicates publishers in England were very interested in large cats involved in imaginary childhood games at that point in publishing history.

Sadly, the 1969 film adaptation of this book has been lost.

MEADOWS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

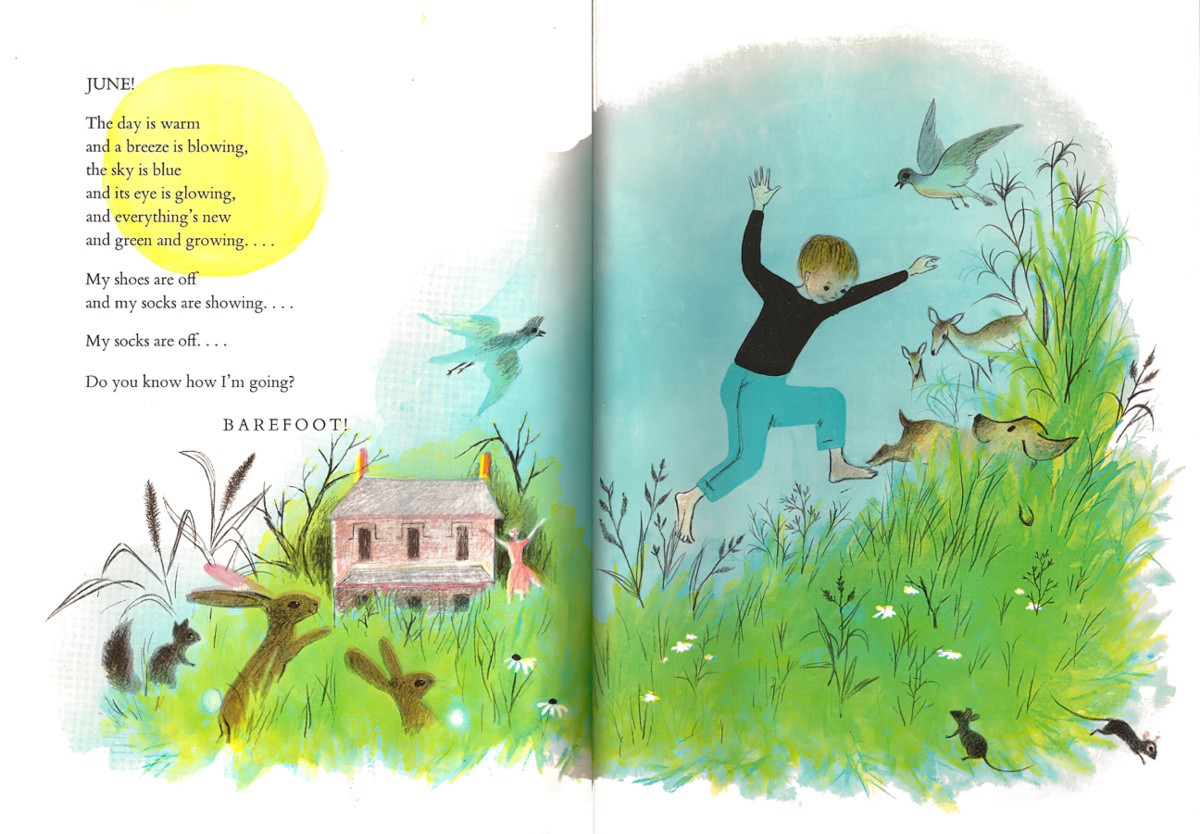

Although this story inverts it, meadows in children’s literature are generally a utopian play space.