Must characters in stories be likeable? No. Are unlikeable characters popular with audiences? Yes. But they’re harder to write. They need to be all of the things listed below and then some.

Some characters in some stories shouldn’t be likeable.

But what if you want to create a genuinely likeable main character who appeals to the broadest base? What if your themes are nothing to do with a reality in which bad people don’t always get what they deserve?

Here are some tips and tricks.

Make use of the trickster archetype

In Children’s Literature, instead of the ‘rogue charmer’ type trickster archetypes per se, we often see child main characters who get into trouble despite their best intentions, and who always maintain a positive attitude against all odds.

Anne Shirley

Anne of Green Gables is a completely unrealistic character in that a child who’d been through such hardship would probably be suffering from PTSD and be irredeemably damaged by the time she reached Marilla and Matthew. This aspect is rendered more realistically in the recent re-visioning Anne With An E. Nut the fictional Anne is loveable because she tries her hardest to please, and we know why she does what she does.

Ramona Quimby

Likewise, Ramona is always getting into trouble despite her best intentions. Ramona is a granddaughter of Anne Shirley.

Amelia Bedelia

Amelia overcomes minor misunderstandings while maintaining her dignity and cheerful attitude

Avoid ‘Whiny’

Editor Cheryl Klein urges children’s authors to avoid ‘whiny protagonists without charm or truth’. The worst thing you can do is have a main character sitting around contemplating things. This is why the Flaneur or the Sunday Wanderer archetype is so difficult to write, though you might try a successful post-modern flaneur a la Weetzie Bat.

But for contemporary child audiences it’s a hard sell. Klein sees a lot of scripts start like this when the character is about to move to a new place, so watch out for that especially if you’re writing one of those kinds of stories.

Give Your Character Authority

Klein writes that in children’s stories voices must have ‘authority’ — ‘a sense that the writer knows where he is going and what she is doing; the feeling that the reader is in good hands.’ She says that authority comes from three things:

- specificity of language

- not wasting the reader’s time

- recognisability (identification)

Bravery, confidence and self-motivation are important for child main characters as they are for the ‘con-man’ archetype:

- Little Bear — illustrated by Maurice Sendak is sweet and plucky, friendly and adventurous

- Nate Wright (a.k.a. Big Nate) — aspiring cartoonist and prankster, exhibits great confidence and creativity

Make Them Interesting In A Virtuous Way

- Billy in Where The Red Fern Grows, who really wants a dog and works tirelessly until he’s saved enough to get one

- Hermione of Harry Potter loves her school work and helps the reader to become interested in magic, too.

Or Make Them Interesting In A Morally Grey Way

Likeable characters may be pessimistic, sardonic, ironic…

- Katniss Everdeen of The Hunger Games doesn’t have much hope for the future at the beginning of the story but she is soon propelled into action.

- Bella Swan is a bit of a Debbie Downer, and also a blank Every Girl, but that doesn’t stop her from being interesting. She still has drive (except when she falls into depression — which the reader quickly skips over because the pages are blank except that they have the words for months on them) by seeking out the company of certain boys in a love triangle.

- The Wimpy Kid has a good, pessimistic handle on his situation in life, and this series is an example of a funny kid with interesting pessimistic energy. This makes him likeable.

I think flawed characters are likeable, because people are flawed. It creates an instant sort of empathy. It’s like when you read Gone With the Wind and Scarlett thinks that the worst thing about the war is how boring it is to hear everyone talk about it. You realize that she’s selfish, and that makes her real.

Katherine Heiny

Show The Readers Your Characters’ Secret Selves

We all have a public, private and secret self. When writers allow readers insight into a character’s secret self readers tend to understand, judge, forgive and then sympathise with the confessor.

This four step progression comes from the work of Dennis Foster who wrote Confession and Complicity in Narrative (1987). Though it applies to fictional characters, it applies in real life as well. This is the astounding power of fiction — when we learn that others have a secret self, and when we learn to empathise with fictional characters via this secret self, we tend to apply these skills to real people.

Give them a moral shortcoming

A likeable character treats others badly. This seems counterintuitive at first. Alain de Botton says that genuine love springs not from admiration of someone’s strengths but from a complete acceptance of their shortcomings. The same is true for fictional characters.

Julie Lythcott-Haims is talking about writing memoir when she offers the following advice, but it applies to your main fictional characters as well as it applies to your memoir:

You have to be okay with your flawed self, and all of the flawed selves in your story. You also have to be fair to everyone else. As my editor told me when I was writing my memoir, “Be the God of all characters,” by which she meant care about everyone equally. Look at every interaction from all angles. Make sure you’re not portraying yourself in rich complexity and everyone else as stereotype. My editor also meant I had to be realistic about myself. She told me, “Readers won’t trust you or root for you unless they know about some of the stupid, shitty, and shameful things you have done.” It felt like a paradox—how are they going to like me if I give them a reason to hate me? But I came to understand her point. All humans are flawed; a willingness to show your own flaws on the page makes you all the more relatable*.

at Jane Friedman’s blog

That said, admiration is still part of why we like someone.

We identify most strongly with characters we feel sorry for, worry about, or like and admire.

Michael Hauge

*Relatable is another word which keeps popping up. Relatability (and likeability) are not useful when it comes to assessing the worth of a work, because these feelings are specific to individual cohorts of readers.

Make them heroic.

“The hero doesn’t become a hero simply because he takes a stand against the villain; he becomes a hero because he stands for something. This can be justice, a cause, his family, friends, community, or nation. Invariably, while the villain stands for himself, the hero stands for something beyond himself.”

Howard Suber, The Power of Film

Make them pretty but not too sexually appealing

Howard Suber also says that although stars of films tend to have sex appeal, characters in films who use their sex appeal to get ahead usually end up dead in the end. In children’s stories, the main character is usually unremarkable in looks — the ‘every child’. Before Kristin Stewart came to represent the character of Bella from Twilight, she was described in very generic terms. She was The Every Girl, with defining qualities to speak of. As unpopular as Bella is among certain, more critical, readers, she is also widely loved.

See: The Appeal of Dark, Paranormal Romance.

I’m describing how to make a character widely ‘likeable’ for an inherently conservative audience, not how to tell a woke, inclusive, sex positive story. For a lengthy rumination on this very topic see my post: Female Beauty In Young Adult Literature

Make them smart but not too smart.

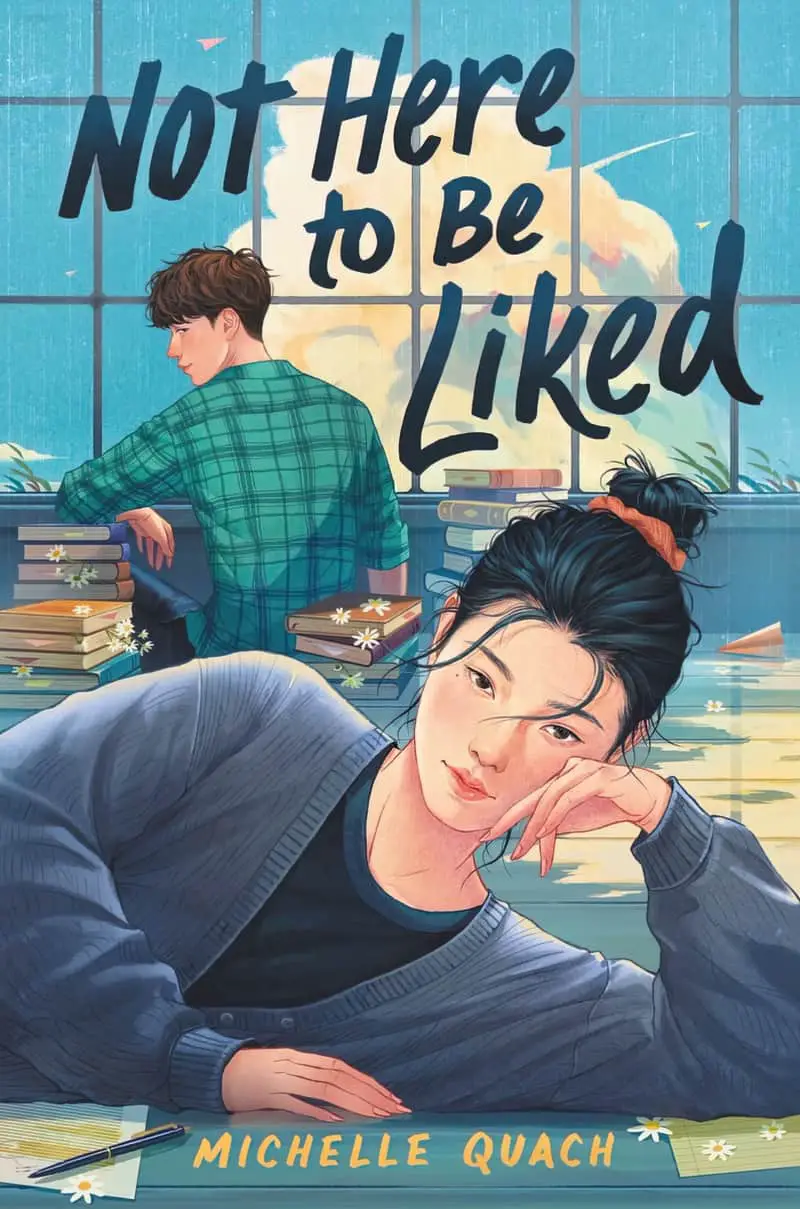

Main characters don’t tend to be super smart. Northrop Frye calls these empathetic main characters low-mimetic heroes. In children’s literature, the self-effacing Greg Heffley is an excellent example, as well as Big Nate and other (mostly boy) characters. Due to well-intentioned but slightly misplaced feminist efforts, girl characters are less often low mimetic heroes who do one dumb thing after another, though we do have Ramona Quimby archetype and granddaughters such as Junie B. Jones, liked for a wide-eyed sort of naivety.

Make their virtues personal achievements rather than privileges.

Education works the same way — a likeable main character doesn’t have to be highly educated. Education isn’t a personal achievement (it’s a luck thing, mostly), so films don’t reward characters simply for being educated.

Suber also points out that whereas people in real life aspire to being rich, in movies characters are punished for this. (Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard). Oskar Schindler is an example of a character who starts off wanting to be rich, but part of his character change is that by the end he’s no longer focused on riches. (He has therefore become a ‘better’ person.) We know Draco Malfoy is no good as a person because he comes from a background of privilege.

Make them self-sacrifice for the greater good.

The hero generally gains little or no reward for their sacrifice — it is the community that gains. To the extent the hero does personally gain from their sacrifice, they cease to be a hero and become simply a smart operator.

Sacrifice becomes sacred when it is truly selfless.

Howard Suber, The Power of Film

Put them in danger and make them experience pain and sorrow.

A lot of popular stories are pyrrhic victories, leaving the hero in a miserable state at the end. (It’s not true that Hollywood films all have happy endings.)

Make them loyal.

Likeable main characters subscribe to the ‘eye-for-an-eye’ policy. As Shakespeare meant it, “If someone takes your eye, you take one of theirs, not both.” (The line is frequently misinterpreted as “If someone takes your eye, you should definitely poke theirs out in retaliation.) Shakespeare was urging moderation in revenge. We don’t seem to mind revenge stories, but we despise characters who take revenge by going way too far.

Cater to Audience Prejudices.

Suber is upfront about the fact that Hollywood writers and producers cater very much to a conservative, particular kind of audience. It helps if your hero is young. And their values need to concord with those of the majority of the audience.

Many of us are ageists when it comes to heroes — we often think of heroes as people who are beyond childhood but not yet into middle age.

Howard Suber, The Power of Film

There is troubling and enduring audience prejudice when it comes to children’s book heroes: The white, middle-class boy as the ‘universal child’. The myth of the universal child must be based on the idea that there is an archetype with which young readers of all backgrounds can relate. We therefore have books disproportionately full of such types.

This is related to the idea that only white boys can be funny, and a lot of the most popular children’s literature is funny: Children of colour can star in tragic stories. Girls can’t be silly.

This state of affairs is changing, but slowly.

Make them a good mediator.

The hero is almost always an intermediary, someone who mediates between different social groups, between man and nature, man and God, or some other constellation of forces. […] Villains, by contrast, are usually well-integrated into their communities, and are often members of its power structure. They belong: heroes don’t. […] To be an intermediary is to always be lonely, because you never truly belong. One of the recurrent paradoxes of heroes is that they so often successfully mediate between contending cultures or value systems, but they often cannot mediate between contending forces within themselves.

Howard Suber, The Power of Film

Make them empathetic, not sympathetic.

Sympathetic means likeable. … We’d want them as friends, family members, or lovers. They have an innate likeability and evoke sympathy. Empathy, however, is a more profound response.

Empathetic means “like me”. Deep within the protagonist the audience recognizes a certain shared humanity. Character and audience are not alike in every fashion, of course; they may share only a single quality. But there’s something about the character that strikes a chord. In that moment of recognition, the audience suddenly and instinctively wants the protagonist to achieve whatever it is that he desires.

The unconscious logic of the audience runs like this: This character is like me. Therefore, I want him to have whatever it is he wants, because if I were he in those circumstances, I’d want the same thing for myself.” Hollywood has many synonymic expressions for this connection: “somebody to get behind,” “someone to root for,” All describe the empathetic connection that the audience strikes between itself and the protagonist. And audience may, if so moved, empathize with every character in your film, but it must empathize with your protagonist. If not, the audience/story bond is broken.

Robert McKee, Story

Okay, make them empathetic, but not too empathetic!

It’s counter intuitive, but audiences prefer that characters show a human failing. That’s why the Mary-Sue archetype no longer works. The Mary Sue probably never really worked for audiences, but was written in didactic stories for children under the belief that children required good modelling in their fictional characters.

(The term Mary-Sue is considered problematic by some.)

The term Mary Sue sees frequent usage in many different fanbases, but in no place other than The Legend of Korra is the truth more apparent: It’s a sexist term, and all you’re really criticizing when you use it is the protagonist for being a woman.

The Mary Sue Criticism of Legend of Korra Is ABSOLUTELY Sexist

Modern thinking is more like this: Children need to see that others have the same emotions and ‘bad feelings’ as they do in order to know that they are not alone in the world. The same applies to adults, actually.

Give them self control rather than power over others.

Self-control isn’t much talked about in comparison to other virtues but we value it highly in ourselves and in others. This is a relative modern phenomenon. We admire those who exert excellent control over themselves.

On the other hand, we revile those who try to exert control over others. We resist those people in real life, and the same is true in fiction.

Michel Foucault’s main legacy is his thoughts about power. He unpicked notions of progress and enlightenment in order to analyse their dark sides. But what he had to say about human sexuality is also interesting and relates to how we have historically considered self-control a virtue.

Foucault believed that sexuality only started to be policed in the 19th century, which (ironically) led to an explosion in people talking about sex, Havelock Ellis et al. Foucault was very interested in how we categorised things. He noticed that people started to be divided into taxonomies according to their sexuality: sadists, masochists, hysterical females, sexually promiscuous females and so on. These categories started to be medicalised. People started to think that by looking at your sexuality you would understand something deeper about yourself. Foucault critiqued that idea. He then studied old texts from antiquity to understand how people thought of sexuality in the past. He discovered that until Havelock Ellis et al came along, people were categorised not according to their sexual orientation, and not according to the type of sex they had, but along a simple binary: Could they control their urges? In the past, someone who could control their sexual urges was considered admirable, like someone who can control their finances — evidence of a person who’s got it all together. Who you slept with, their gender, your fantasies, none of that came into it.

It’s interesting to consider the extent to which we admire those with self-control today, versus how we (via our governments) punish people who do not exhibit self-control, be it over substance use, sex, or personal finances.

In fact, it’s difficult to think of an anti-hero who does not have self-control. This anti-hero may be morally wrong, but on some level we can still admire their great self-control when it comes to exacting revenge and evildoings.

Don’t Write A Powderpuff

Powderpuff. The authorial habit of being too nice to characters about whom the author cares. Violates the basic principle, if you want your reader to care about your characters, do horrible things to them early on. Also called Pitty-Pat. (CSFW: David Smith)

A Glossary of Terms Useful When Critiquing Science Fiction

Make Them Observant and Witty.

Perspicacity: The quality of having a ready insight into things; shrewdness.

Roger Fry [valued children’s perspectives because] he found in children a capacity to observe without interpreting.

Juliet Dusinberre

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” is a Victorian fairy poem and, coincidentally, O.G. To T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. In this context, ‘childe’ refers to a young man who has not been knighted. He is a modern young adult.

In this poem, Roland is having a pretty crappy time. But he perseveres on a hopeless journey because, like many a modern young adult character, “naught else remained to do”.

What else does this old poem by Robert Browning have to do with modern young adult characters?

This: Roland alone is able to see through the façade which fools everyone else. (Specifically, Roland gets magical help from Merlin and is able to rescue his sister.)

Audiences still enjoy this character archetype today, who can see a situation for what it is. I can think of a number of modern young adult Rolands, featuring main characters commonly described as sarcastic or sardonic. But there’s more to them than that. I don’t even think sarcastic and sardonic are the best words to describe these characters, because they’re not always ‘mocking’ per se:

Sarcastic: marked by or given to using irony in order to mock or convey contempt

Sardonic: grimly mocking or cynical

Here’s what these characters definitely do have in common: They are perspicacious: insightful, shrewd and at least a little bit streetwise. Audiences love a smart character, but not when they’re too smart. The streetwise character with average grades is a perfect 10 in terms of likeability. On Northrop Frye’s scale they are basically low mimetic heroes, but with this one superpower: a winningly shrewd cynicism.

Examples of the Perspicacious YA Character

- Bliss Cavendar of Whip It!

- Lindsay of Freaks and Geeks

- Sydney of I Am Not Okay With This

Often these stories begin with the insightful main character outlining their situation in life, their world, and where they fit into it right at the beginning of the story. They are probably going to be wrong about something, and require some sort of character arc. But for now we mostly believe them at face value.

Below, in the trailer to I Am Not Okay With This, Sydney tells us she’s a ‘boring white girl’. This creates an ironic distance between Sydney and what she says about herself — in the image, she appears to be running through a town at night covered in blood (ie. not boring). However, the phrase ‘white girl’ clues us into the fact that she understands her own white privilege, at least. (An important lemme-off-the-hook attribute for a white girl main character with a Black best friend.)

Sydney also tells us in episode one that she recently moved to Pennsylvania, “but not a cute part of Pennsylvania”, rather to a town which has won American’s worst air quality for a number of years in a row. To be able to make such a statement she demonstrates an overview knowledge of Pennsylvania (understanding of geography), as well as how people think about Pennsylvania (understanding of psychology).

These young adult characters are able to see their situation as if from above, know where they fit into society and exactly what fresh hell they’re living in. The optimism of their peers seems ridiculous to them, often because they arrive to us with a big ghost e.g. the death of a family member. We presume this recent trauma is the exact thing which elevates them above the smalltown, petty views shared by most of their peers.

Much has been said about the manic pixie dream girls given to men, but these perspicacious YA characters are often girls.

Storytellers frequently pair them up with a more happy-go-lucky sidekick. In Sydney’s case, it’s Stanley, described as giving ‘zero fucks’. These character are quirky outcasts in their own right. Perhaps we might even call them pixie dream boys.

It is their superpower to see the snail under the leaf which enables YA main characters to enact good for their communities.

In his voiceover narration to The End of the FXXXing World, James already has the insight to tell us that he is a psychopath — a conclusion he has drawn without psychological intervention. A girl from school, Alyssa, drags him on a rebellious road trip and is rude to a waitress in a cafe, at which point James tells us that Alyssa has some issues. Ironically for the audience, whatever ‘issues’ Alyssa has, James has bigger ones. So despite his self-insight, he can’t see that he has one massive big issue of his own. But audiences can still respect him for his ironic perspicacity.

Any young adult character who gives the viewer a guided tour at the beginning of a film is probably a perspicacious character though, again, they will be wrong about something. Another example is the opening to 10 Things I Hate About You. Michael has insight into the high school’s social groups only because he has been excluded from all of them:

(The genuinely insightful YA character of 10 Things I Hate About You is Kat.)

This perspicacious character works especially well when they are funny with it. Take the opening paragraph of Will Grayson, Will Grayson, in which the mock-sage fatherly advice is upended:

When I was little, my dad used to tell me, “Well, you can pick your friends, and you can pick your nose, but you can’t pick your friend’s nose.” This seemed like a reasonably astute observation to me when I was eight, but it turns out to be incorrect on a few levels. To begin with, you cannot possibly pick your friends, or else I never would have ended up with Tiny Cooper.

John Green and David Levithan

THE HIGHLY OBSERVANT PICTURE BOOK CHARACTER

“It is quite possible that an animal has spoken to me and that I didn’t catch the remark because I wasn’t paying attention.”

E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web

Is this YA archetype a more grown-up version of Eloise (PB) and Harriet the Spy (MG)?

Both Kay Thompson’s Eloise (Billed as “A book for precocious grown ups”) and Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy stand as models for the life of the New York Upper East side child living in an adult sphere with minimal parental involvement. Eloise’s mother who “is 30 and has a charge account at Bergdorf’s” seems to be perpetually absent, although mentioned frequently in terms of whom she “knows”. The book begins with this introduction: “I am Eloise/ I am six/ I am a city child/I live at The Plaza”. Eloise as the quintessential New York self-defined “city child” protagonist is spunky, talkative, imaginative, precocious, curious, mischievous and vastly self-absorbed. Like Harriet, Eloise is a keen participant in and observer of the adult world in the hotel where she lives. The Plaza becomes its own playful and imaginative world for Eloise where the busboys, musicians, maids and nanny reveal random stories and information about urban life.

Naomi Hamer

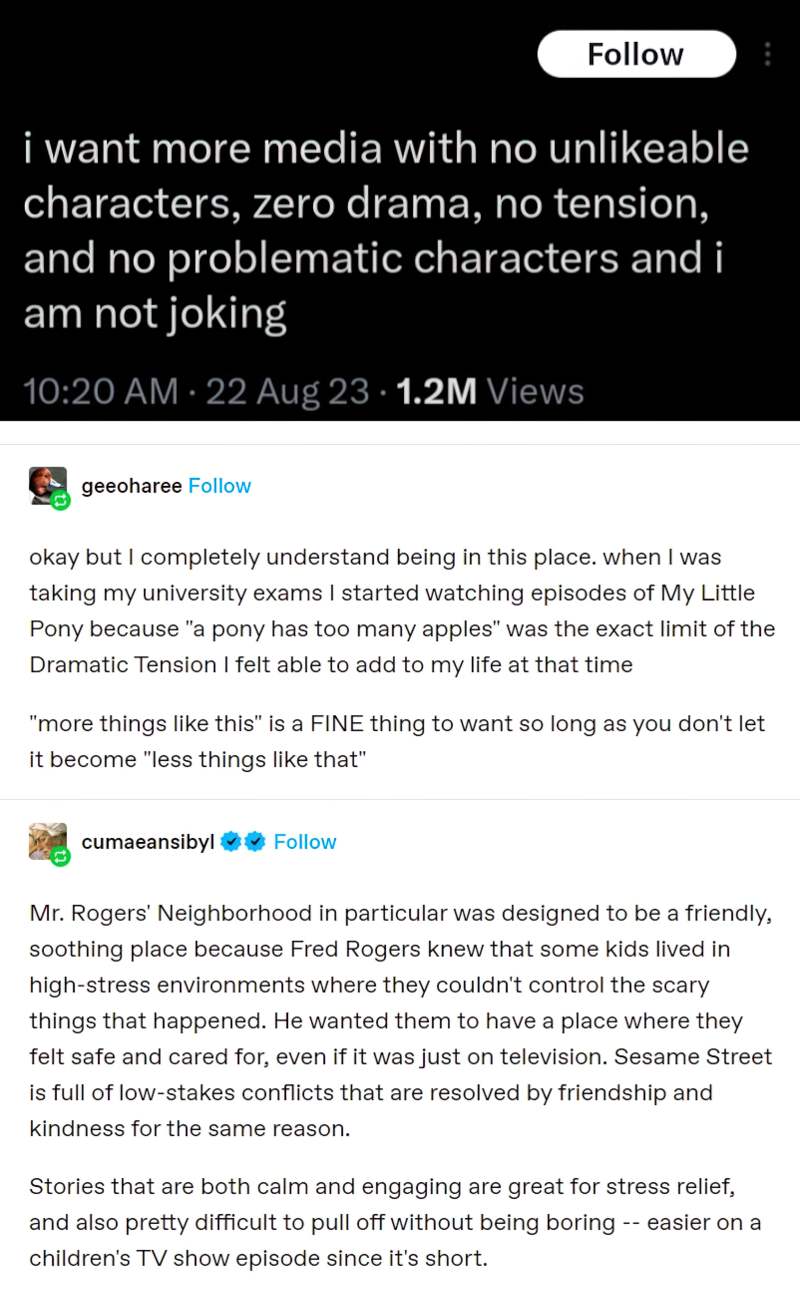

THERE’S A PLACE FOR LIKEABLE CHARACTERS

Related

How to edit your movie to create empathy

The Dehumanizing Politics of Likability by Teow Lim Goh from Los Angeles Review of Books

Header painting: George Bernard O’Neill — Stolen Fruit is the Sweetest