Liars are everywhere in stories. Stories themselves can be considered giant lies (which tell a deeper truth). The trope of the mask is a part of all this. Certain genres demand a ‘mask’, or, lying.

That’s because entire genres are about finding out the truth:

- Detective Crime is all about deciding whose version of a story is the truth. Our crime fighting heroes always care deeply about the truth.

- Mystery asks “How can we come to know the truth?” (By definition, a mystery is simply something that defies our usual understanding of the world.)

- Anti-Westerns critique the story given by classical Westerns and ask us to consider the truth about The Wild West (that it was a brutal, unjust, hellish place)

- In magical realism characters—especially the narrator—might not know what is happening any more than the reader, so they are discovering the truth of their reality as they go along.

- In a thriller, the perpetrator is known, but his guilt is not absolutely certain—or the hero wishes not to accept the truth of his guilt. (The uncertainty enhances the suspense.)

- Superhero stories are wish fulfilment fantasies in which everyone eventually ‘learns the wonderful truth about me’ (I am amazing when you unwrap my everyday clothes and put me in lycra).

- In many comedies a hero will be wearing some kind of ‘mask’ but eventually, after some sort of spiritual crisis, this mask will be ripped off and the other characters will learn who this hero really is.

- A parable illustrates a simple truth for teaching purposes.

- Absurdist stories focus on the experiences of characters in situations where they cannot find any inherent purpose in life, most often represented by ultimately meaningless actions and events that call into question the certainty of existential concepts such as truth or value

- Drama is often about the difference between a character’s public persona and what’s really going on underneath. We watch drama to learn about the lives we never find out about in our real-world acquaintances.

- Cinema in general

The cinema cannot show the truth, or reveal it, because the truth is not out there in the real world, waiting to be photographed. What the cinema can do is produce meanings and meanings can only be plotted, not in relation to some abstract yardstick or criterion of truth, but in relation to other meanings.

Movies and Methods: An Anthology Vol. 2

THE TRUTH DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FICTION AND REALITY

Fictional stories are make believe on the surface but true underneath. Real life, on the other hand, may be believable on the surface but is often unbelievable underneath. … In movies, screenplays and novels, we need to know the inner truths of the characters. Your characters’ actions in response to whatever incredible situation you’ve created must be reasonable, justified and believable.

Michael Hauge, Story Mastery website

The most dangerous untruths are truths slightly distorted.

G.C. Lightenberg

TRUTH AND STORY STRUCTURE

Within a story structure, the truth will be revealed at the ‘Self-Revelation‘ stage. (After the Battle, before New Situation.)

Sometimes the audience is let in on the truth of the situation at the beginning of a story. For instance, in some crime stories the reader knows who the villain is from the get-go. This type of detective story is no longer a whodunnit but a whydunnit.

Because that’s the thing about Scooby-Doo: the bad guys in every episode aren’t monsters, they’re liars. I can’t imagine how scandalized those critics who were relieved to have something that was mild enough not to excite their kids would have been if they had stopped for a second and realized what was actually going on. The very first rule of Scooby-Doo, the single premise that sits at the heart of their adventures, is that the world is full of grownups who lie to kids, and that it’s up to those kids to figure out what those lies are and to call them on it, even if there are other adults who believe those lies with every fiber of their being. And the way you wihn isn’t through supernatural powers, or even through fighting. The way that you win is by doing the most dangerous thing that any person being lied to by someone with power can do: you think.

Ask Chris #81, Scooby-Doo and Secular Humanism

TRUTH TROPES IN STORYTELLING

LIAR TROPE 1: NOBODY BELIEVES THE HERO

COMMON CHARACTER ARC: The underdog hero must take matters into their own hands, saving the day somehow. Only by proving themselves truthful will be finally be accepted by their community.

This is basically the plot of every episode of Courage The Cowardly Dog. It works. Frankly, how quick would you be to trust someone who said there was a flying saucer in the field next door? This initial disbelief is almost mandatory — a type of lampshading for the audience who would otherwise think, “Now who would believe that?”

In 1965, Susan Sontag wrote five steps in one kind of typical science fiction story. Her first two steps demonstrate this lampshading:

- The arrival of the thing. (Emergence of the monsters, landing of the alien space-ship, etc.) This is usually witnessed, or suspected, by just one person, who is a young scientist on a field trip. Nobody, neither his neighbors nor his colleagues, will believe him for some time. The hero is not married, but has a sympathetic though also incredulous girlfriend.

- Confirmation of the hero’s report by a host of witnesses to a great act of destruction. (If the invaders are beings from another planet, a fruitless attempt to parley with them and get them to leave peacefully.) The local police are summoned to deal with the situation and massacred.

When it comes to heroines, however, writers often add a little extra. Like mental instability. The 2012 film Gone, stars Amanda Seyfried as a damaged young woman who takes on the role of a vigilante cop after the actual cops think she’s fabricated a former abduction from which she managed to escape. Even the movie poster announces that ‘no one believes her’.

LIAR TROPE 2: HERO LIES TO THEMSELVES

COMMON CHARACTER ARC: Over the course of events the character is liberated by accepting the truth of their circumstances.

In Strays Like Us by Richard Peck, the main character has been abandoned by her mother — a drug addict criminal who will never step up to the plate for her adolescent daughter. Over the course of one year in a settled environment with a new female role model, Molly Moberly must come to terms with this. Finally she gives away the notebook she has been using to create a fictional narrative about her mother.

Jacqueline Wilson also writes of a girl lying to herself about her mother in Starring Tracy Beaker.

The mother of these orphan girls with imaginative narratives about their hopeless mothers is perhaps The Great Gilly Hopkins by Katherine Paterson.

In Big Little Lies, Celeste (Nicole Kidman) lies to herself about the nature of her relationship with her husband. All of the supporting characters are keeping their own secrets.

LIAR TROPE 3: HERO LEARNS WHEN NOT TO LIE

COMMON CHARACTER ARC: The main character has learned not to lie as a child but as she enters adolescence she realises the world is not black and white, so she learns when to keep quiet in order to protect someone else.

Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolk is an excellent example of this storyline in a children’s book.

Another example, likewise a literary middle grade novel, is Lenny’s Book of Everything by Karen Foxlee. With her mother and little brother caught up in the story of the brother’s health issues, main character Lenny goes to visit a great aunt from her estranged father’s side of the family. She now faces a moral dilemma: To tell her mother and Davey or not?

But an entire great aunt. An entire person, all bony and angular and whiskery and filled with cackling laughter. All nylon stockings and strange orthotic shoes. All stories and sizzling bacon fat and radio violins. That secret was huge. Each time I looked at Davey, I knew I had to tell him, but each time I went to tell him, my thoughts clogged up. The secret sat on my tongue like a spoonful of peanut butter.

Karen Foxlee, Lenny’s Book of Everything

Middle grade books are often all about exploring whether a child is a deontologist or a consequentialist.

DEONTOLOGY AND CONSEQUENTIALISM

Deontology: The study of the nature of duty and obligation to society or to a system of rules to determine right from wrong.

Consequentialism: A doctrine suggesting that the morality of an action is best judged by its consequences.

The thought experiment most often used to describe the difference between deontologists and consequentialists goes like this:

You’re harboring an innocent person accused of being a criminal. Police turn up at your door. The police ask, “Are you harboring a criminal?”

If you’re a deontologist you think to yourself, well, I shouldn’t really lie because I’m against lying, but it’s important to keep this innocent person safe. So you lie. You can justify your lie.

If you’re a consequentialist you think to yourself, well, sure, this person is innocent but I never lie. So you hand the person over to the police. For you, honesty is inherent to who you are and takes precedence over all else. External conditions don’t have any bearing on your decision.

LIAR TROPE 4: FAKE ALLY LIES TO HERO

COMMON CHARACTER ARC: In children’s books it is often the adult lying to the child ‘in order to protect’ them.

In Strays Like Us even sympathetic adult Aunt Fay lies to Molly by omitting the fact that her mother has checked herself out of rehab and has gone AWOL. Because Peck wants to keep Aunt Fay as a sympathetic character, he has Aunt Fay apologise to Molly for not telling her earlier.

Also in school stories there will often be a ‘bitchy teen girl’ trope who is ‘nasty nice’. Tina Fey’s Mean Girls is well-known for introducing this dynamic to the public consciousness.

Eventually the hero works out what the truth of the situation is, and this contributes to their character arc. Or, like Lindsay Lohan’s character on Mean Girls, she might be a trickster archetype who lies back to her opponent in order to exact revenge.

LIAR TROPE 5: THE FAKE OPPONENT BENEFACTOR

It comes from Jane Austen:

The obvious liar in Pride and Prejudice is Wickham, but the more interesting from a plot perspective is Darcy. Because Darcy does something immensely noble, which if she knew about it would make Elizabeth deeply grateful to him, but doesn’t tell her. Lies about it. She only finds out indirectly. It’s a heart-stirring and deeply effective device, so much so that it has spread, meme-style, through countless other stories ever since. There’s a legend in Bookworld that when Helen Fielding was considering turning her Bridget Jones columns into a book, she saw the Colin Firth-starring TV adaptation and decided to lift the plot from Pride and Prejudice. Virtually every romantic novel ever since has done the same, including Twilight.

The Guardian

Secret-Keeping And Lies In Children’s Literature

Many books for children explore the ideas of truth, lies and secret-keeping. Young characters commonly keep secrets from adults. Often (especially in portal fantasy) it’s because the adults simply wouldn’t believe the children (that there’s a world on the other side of the wardrobe; that there’s a creature who grants wishes that last for a day). This is a ‘plot level’ secret, and serves to keep adults out of the story. That’s one of the main challenges for children’s authors — keeping adults from solving all the kids’ problems.

In other stories, secrets are thematically and didactically explored.

It’s an accepted fact in child development that humans are not born liars. We do not have the capacity to lie until we have developed theory of mind. Once we have learned to lie, we usually do it badly. Gradually, over the course of childhood, we learn that — even if the rule books say differently — lying is at times necessary. There is good lying and bad lying, or at least, lying that will get you into trouble and lying that will get you out of trouble.

This is complicated stuff. It’s no wonder so many of the great works of children’s literature touch upon it. Some stories are all about the lying.

Magnolia Moon is very good at keeping secrets.

She knows knows Just what to do with them, and has a way of talking to the jumpy ones to stop them causing trouble.

Which is why people are always leaning in and whispering: “Can I tell you a secret?’

Edwina Wyatt introduces a character whose irrepressible joy and vivid imagination will remind readers just how much can happen in a year of being nine.

A Few Case Studies of Lying In Children’s Literature

Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce

In Tom’s Midnight Garden Tom’s Aunt and Uncle tell him there is nothing in the yard except for a small area of pavement and some rubbish bins, so when Tom finds a vast, rich fantasy world after opening the back door at midnight, he is incensed that he was lied to. Tom already has a keen sense of right and wrong. When he has his Aunt and Uncle on about it, they have no idea what he’s talking about. When Tom shows them the other world it is no longer there.

In this way, Tom’s sense of reality, as well as his black and white sense of ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’, is challenged. Tom’s Aunt and Uncle aren’t lying, even though they can’t see the truth right in front of them, because that is just not their reality.

The Chronicles Of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

A similar event occurs in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, of course, when Lucy takes the other Pevensie children back to the wardrobe only to find the back has closed up. Lucy is heavily penalised for lying until it is proven otherwise. Edmond pays the greatest price for the greatest lie — knowing the world of Narnia exists without reporting the truth of it to Susan and Peter, redeeming Lucy in their eyes.

Northern Lights by Philip Pullman

The Dark Materials trilogy is all about shades of grey over black and white. She is smart and spirited and plucky and at times is a quick thinker but she is also naive and is still learning who to trust with the truth. Before she runs away from Mrs Coulter she is summoned by a man called Lord Boreal. He asks her questions.

“And is Mrs Coulter keeping you busy? What is she teaching you?”

Because Lyra was feeling rebellious and uneasy, she didn’t answer this patronizing question with the truth, or with one of her usual flights of fancy. Instead she said, “I’m learning about Rusakov Particles, and about the Oblation Board.”

The man presses her to tell him what she knows about that.

“Did Mrs Coulter show you a picture like [a photogram where you can see Dust]?”

Lyra hesitated, for this was not lying but something else, and she wasn’t practised at it.

As you can see, Pullman makes a distinction between run-of-the-mill lying and something deeper and unnamed — I’ll call it Preserving The Truth.

Lyra gets more worldly over the course of the story, as all main characters must in myth-structured stories. She naturally learns how to lie, sometimes to comic effect and sometimes because it is a matter of life and death.

After Lyra runs away she is approached by another suspicious man who tries to spike her coffee. To the delight of the reader, Lyra has already told the man that her name is “Alice” and that her father is “a murderer”.

“I told you, he’s a murderer. It’s his profession. He’s doing a job tonight. I got his clean clothes in here, ’cause he’s usually all covered in blood when he’s finished a job.”

“Ah! You’re joking.”

“I en’t.”

General Examples of Secret-keeping In Children’s Stories

- Secrets are dangerous and should be shared with a trusted individual such as a parent, teacher or friend. This is a non-controversial message about secrets and a safe one to put in a book. No parent likes to think that their young child is keeping secrets from us. Parents are terrified of grooming and we no longer automatically trust teachers, coaches and bus-drivers. We like to think our children will tell us everything. Gatekeepers of children’s books therefore like books with this message.

- However, sometimes secrets are even more dangerous to share than to keep, and this danger can affect others as well as the secret-keeper.

- Even though it’s best to share your own secrets with friends, your friends‘ secrets should never be shared with others even if you feel you yourself need psychological support. Once you pass on a ‘secret’, it’s no longer a secret.

- Among groups of friends, secrets are swapped (even complete fabrications) as a mode of toxic bonding. Mean Girls features a Burn Book, for example, started by Regina George for two reasons: First it establishes a social hierarchy with herself at the top and second it bonds a small group of insiders together, using shared ‘knowledge’ as currency. People (mostly female characters) who use secrets and lies as social currency deserve every horrible thing that comes to them, and readers should never imitate this behaviour in real life. These stories exist to show readers that it happens, why it happens, and asks them to criticize the practice. There is also that wish-fulfilment of retribution in Mean Girls, when Regina George finds she’s met her match in the down-to-earth newcomer whose social gullibility turns out to be her strength. Machiavelli agreed that lies always hurt the teller, and Aesop agreed.

- Is lying by omission to help someone else a good secret or a bad secret? Not all secrets are the same. They come in different colours — black, white and grey. Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolk does a good job of exploring this line of thought. The Case For Teaching Kids To Lie, Just Like Adults, from Fatherly.

- If you try to keep some horrible deed secret then get caught out, don’t deflect blame. Lying for your own gain and only your own gain means you deserve retribution. Pig The Fibber by Aaron Blabey is a humorous picture book example of this message.

- If you have suicidal thoughts or have been abused then you should never, ever keep that secret. That’s the message of 13 Reasons Why. The TV adaptation comes with messages about the existence of Lifeline, a mental health helpline.

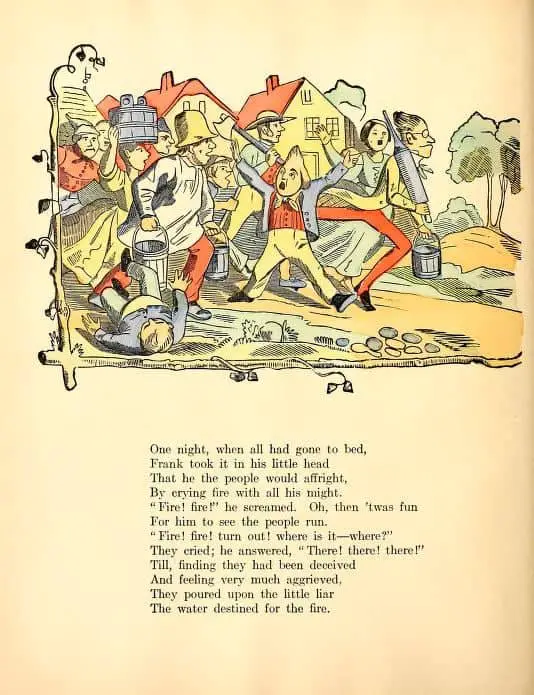

- Perhaps the most famous liar in children’s literature is Pinocchio, whose nose grows longer whenever he tells a lie. The image of a growing nose has entered the public consciousness and idiomatic language, regardless of whether we’ve ever read the story or not. The messages about lying are complex in this classic. Pinocchio is not the only liar. Gepetto sells his winter coat (which he needs) in order to buy Pinocchio a school book but he tells Pinocchio the coat was too hot anyway. Presumably this lie is okay, because it’s a ‘white lie’, designed to avoid a child feeling bad and help him in the noble goal of getting an education. For more on lying in Pinocchio, see here: “Lies that have short legs are those that carry you a little distance but cannot outrun the truth. The truthful consequences always catch up with someone who tells a lie with short legs. Lies that have long noses are those that are obvious to everyone except the person who told the lie, lies that make the liar look ridiculous.”

- While children should never lie to parents, if (good) parents lie if it’s to protect children.

- Beware ‘tricky’ adults. An example of a nasty-nice stranger who reels a child in with lies is the White Witch, who reels him in with Turkish delight than tells him to keep a secret. The secret-keeping leads to Edmond being ostracised by his family when they find out he’s been lying about the existence of Narnia. The message in C.S. Lewis’s Christian works is that lying is always bad and will always be found out. We are often told that lies will always be outed. This stems from the monotheistic view of the omniscient eye watching our every move, reinforced by the idea that all our bad deeds will be judged upon our death. But not everyone holds these views. Do lies really always come out? Is there some law of ‘physics’ which makes that happen? Or perhaps this is far, far from reality — many secrets and lies die everyday around the world, along with the people who’ve been keeping them. And were they right to keep them?

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Notion of The Living Truth

Bonhoeffer argues that it is naive and misleading, perhaps even dangerous to suppose that the literal truth always or even typically conveys what we mean when we talk about telling the truth. Of course we often tell a straightforward lie, and for morally blameworthy reasons. But we also often make statements that are not literally true—that are in fact literal lies—while conveying a deeper truth that an honest statement of the facts could not communicate. So, for example, if Geppetto told Pinocchio, “I sold my coat in order to buy you a schoolbook,” he would be speaking the literal truth, but his meaning might well be (or be understood by Pinocchio as) “Look what sacrifices I make for you!” By telling Pinocchio that he sold his coat because it was too hot—a lie—he communicates to Pinocchio something like “My coat doesn’t really matter to me, and your schoolbook does, and I don’t want you to feel bad about the fact that I sold my coat.” This is a very nice example of what Bonhoeffer means by the living truth, the more important meanings in communication that may not, and sometimes cannot, be conveyed by strict reportage. So many of the stories we tell our children are of this kind—Santa Claus is the obvious example—and we should ask ourselves, as parents and also as lovers: How many stories might my child, or my boyfriend, or my partner, or my mom be telling me, not in order to mislead me but rather to tell me something that, if said outright, might be misunderstood or cause me harm?

The New Yorker

Apart from Pinocchio, can you think of some children’s stories which play with the concept of ‘the living truth’?

At what age can (neurotypical) children understand this concept? For many autistic children, development is atypical when it comes to social lying. When you live with an autistic child you realise the extent to which everyday communication runs on secrets, lies, omissions and short-cuts as social niceties. Autistic readers in particular can benefit hugely from children’s literature which explores the full gamut of ideologies around secret-keeping and lying.

What does the field of psychology tell us about the toll of secret-keeping?

Traditionally, scientists have studied secrecy as a social act, as the wilful hiding of information from others. According to this view, it’s the suppression of the secret—the keeping it in, the self-monitoring, and the tactical contortions that go with it—that exact a cost on the keeper. But Slepian argues that secrets cause suffering in other ways, too. Yes, there are occasions when you have to actively steer a conversation away from the rocks, like when you’re attempting to disguise from your office mates the fact that you’re looking for another job. But most of the time you’re by yourself with your secret, thinking about the many ways in which it could be discovered or you might accidentally let it slip. […]

It is established that keeping a secret can take a toll:

Secrecy, as they see it, is less an activity than a state of being. We don’t keep secrets; we have them. And what’s harmful about a secret isn’t the content so much as the mind’s need to keep revisiting it and turning it over—not the murder itself but the incessant beating of the telltale heart. […]

However, if the secret-keeper is able to avoid ‘dwelling’ on it — if the secret isn’t actually bothering them — well, no problem? We shouldn’t assume that keeping secrets is always going to be harmful for the keeper. It depends on the secret and on the person:

By a margin of two-to-one or more, people dwelled on their secrets on their own time far more than in social situations. And the dwelling, more than the concealing, hurt their sense of well-being. By constantly chewing over a secret, Slepian suggested, people remind themselves of their own deceptiveness; they feel “inauthentic, disingenuous.” […]

Other people, or the same people in different situations, might be better off sharing secrets to avoid letting it harm their sense of integrity. This may apply in particular to sharing with others who we really are. For example, living one’s whole life concealing sexual orientation/identity is going to take a very real emotional toll on a person:

Secrets are largely solitary creatures and can be tamed with company. “Talking about it with another person will really go a long way,” he said. Melissa Ferguson, the Cornell psychologist who studied the cognitive and physical effects of concealing one’s sexual orientation, added that we shouldn’t lose sight of the costs of social secrets.

The New Yorker

On the other hand, for many young gay and transgender people around the world, coming out to their families and communities is more physically dangerous than the secret-keeping is emotionally dangerous. In which case, what is the answer for those readers looking for similar lives within books? Dan Savage, well-known gay sex columnist, often advises young people from bigoted communities be very careful about coming out, as it can lead to loss of educational opportunities, homelessness and physical harm. The time for coming out can occasionally be postponed a few years.

Alongside all those stories about unburdening, stories about secret-keeping — at least for a while — are also needed.

FURTHER READING ON LIARS AND LYING

- The Tech of TV News Might Make It Easier for Pundits to Lie

- Amanda Knox: What’s in a face? from The Guardian

- How To Be More Paranoid from The Hairpin, in which Pamela Meyer tells you how to spot liars.

- Twelve Completely Foolproof And Not-At-All-Crazy Ways To Make Sure He’s Not Lying from Jezebel: Relationships

- Do People Really Want You To Be Honest? from HBR

- Why We Don’t Always Tell The Truth, also from HBR

- 12 Lies To Stop Telling Yourself from Marc And Angel Hack Life

- The ‘Pinnochio Effect’ Confirmed from Science Daily

- Lying Is Common Age 2, Becomes Norm By 3, from BPS Research Digest

- How Money Makes You Lie And Cheat from Time

- The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone—Especially Ourselves from Farnam Street

- 10 Lies You Were Tricked Into Believing from Marc and Angel

- The Lie Detector Paradox from Mindhacks

- Dan Ariely on the Truth About Dishonesty, Animated from Brainpickings

- How we teach our kids that women are liars from Role Reboot is a mostly broken page now, but you can still find it. (And then I read this unrelated passage in a popular science book: Human females, unlike most of their primate relatives, do not tell the truth about when they are fertile. Female chimpanzees flaunt swollen backsides and genitals for the several days in each cycle when an egg is ready to be fertilised… Women, unlike chimpanzees, advertise their potential for copulation at all times, fertile or otherwise. Perhaps a false statement of fecundity means that a male will choose to stick with a particular mate in order to keep others at bay, rather than to make a switch to a third party while his partner is unable to conceive.’ -page 151-152 of The Serpent’s Promise by Steve Jones. #CasualSexism

- Here’s What You Need To Know About Liars from Business Insider talks about two different kinds of liars: polite, everyday liars and ‘prolific’ liars. Given the dominant cultural narrative about how women lie (about being raped, about liking computer games, about liking sex etc.), I’d like to point out that men are statistically more likely to be prolific liars.

- I love children who lie for no reason by Elena Ferrante

- Intricacies of Lying: False Descriptions Easier to Remember Than False Denials from Science Daily

When people say “believe women” a lot of them really mean “believe women until they try to unmask someone I like.”

The Profane Feminist (@ProfaneFeminist) November 22, 2019

Here’s the thing about The Woman In the Window: It’s a great chance to talk not about how women aren’t believed, but specifically how mentally ill women aren’t believed. It’s my latest on @BitchMedia

Originally tweeted by s. e. smith (@sesmith) on May 20, 2021.

There are many songs dedicated to the idea that women are (sexy) liars.

She stabbed the butter lightly before spreading it on a scrap of French bread — ‘why, when I first met you and you told me about yourself, did your story end when you left your wife and went and lived in a flat somewhere? Why was that the end of the story when it wasn’t the end at all?’

‘How do you mean?’ He had stopped eating, though, she noticed that. ‘I did go and live in a flat when I left my wife.’

‘Indeed you did. But there was more to it, wasn’t there? You left your wife and you went and lived in a flat. Then you met someone else and got married again and went and lived in a large house somewhere else entirely.’

‘Oh that,’ he said. ‘Well, perhaps we got interrupted at that point. Perhaps I just forgot to tell you the rest and you never asked.’

from The Lonely Margins Of The Sea by Shonagh Koea

Header painting: Charles Haigh Wood – Fair Deceivers