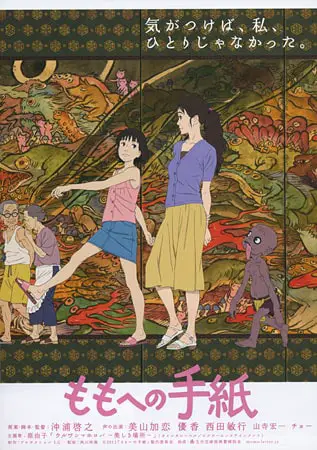

Letter to Momo is a 2011 Japanese feature anime directed by Hiroyuki Okiura, also known for Ghost In The Shell. After the oceanographer father drowns in a disaster at sea, mother and daughter move from Tokyo to the small island village where the mother spent holidays once per year with her aunt and uncle to recuperate from her asthma as a child. Creatures from Japanese folklore appear to guide young Momo through the grieving process, in this story intimately connected to Japanese Buddhist and Shinto traditions.

SETTING OF LETTER TO MOMO

Japan is an archipelago of about 3000 islands — five main ones, of course. The director himself grew up on the coast of Hiroshima, which means the edge of the Seto Inland Sea.

Letter To Momo is set on a small island in the Seto Inland Sea of Japan — the body of water separating the islands of Shikoku, Honshu and Kyushu. The real island is called Osaki-Shimojima, whereas the fictional island is shortened and changed slightly to Shiojima.

Though the island is fictional, the landmarks and art are closely based on the real island. For example, Historical Nomieruoka Park is depicted in several scenes. The real island has an area of about 18 square kilometres and a population of about 3,000 people as of 2012. There is a Buddhist temple at its highest point (Mount Ippooji).

The Name Of Shiojima

The name of this island is Shiojima. The first character of Shiojima (汐島) means both ‘tide’ and ‘opportunity’. This is the sort of symbolism which doesn’t translate easily into Western narrative and is part of what makes Chinese characters so hard (and fascinating) to study. In Eastern Asia, the fact that the tide is connected to opportunity maps onto this story starring two characters who return to the sea for a second chance at a full life, even after great loss. And even after the great loss was due to the sea. The history of this connection is to do with Japan’s close historical connection to the sea, and their heavy reliance upon fishing. The difference between having enough to eat or not was all about judging the ebb and flow of the tides.

If you look up a Japanese-Japanese dictionary you’ll learn that 汐 refers specifically to the ebb of evening tide, and is associated with a beautiful view. This makes sense, since the character is made up of the radical for ‘water’ next to the character for ‘evening’. If you write some Japanese you can probably guess the character for morning tide. Yep, it’s 潮. Both words for tide are pronounced the same way — either ushio or shio. In everyday Japanese both are used and no mind is ordinarily given to whether the tide is an evening or a morning one. The character for morning tide seems to be more the default.

汐 is often used in girls’ names, which makes it worth knowing. The character conveys ‘softness’ and has relatively few strokes, making it convenient to write. The character itself, when written in calligraphy, is of a curved shape, which makes it feminine. You’ll find it in names such as Shiori (汐里、汐璃、汐莉), or in combinations pronounced Shiomi and Shione. In names, confusingly for foreigners, this character might alternatively be pronounced ‘Kiyo’. So you’ll find it in names like Kiyomi, Kiyora. When found in boys’ names it will always be pronounced Kiyo, occurring in names like Kiyoharu and Kiyohiro. When used in a boys’ name, ‘evening tide’ will be paired with a character with traditionally masculine virtues, presumably to offset the feminine associations with ocean tide.

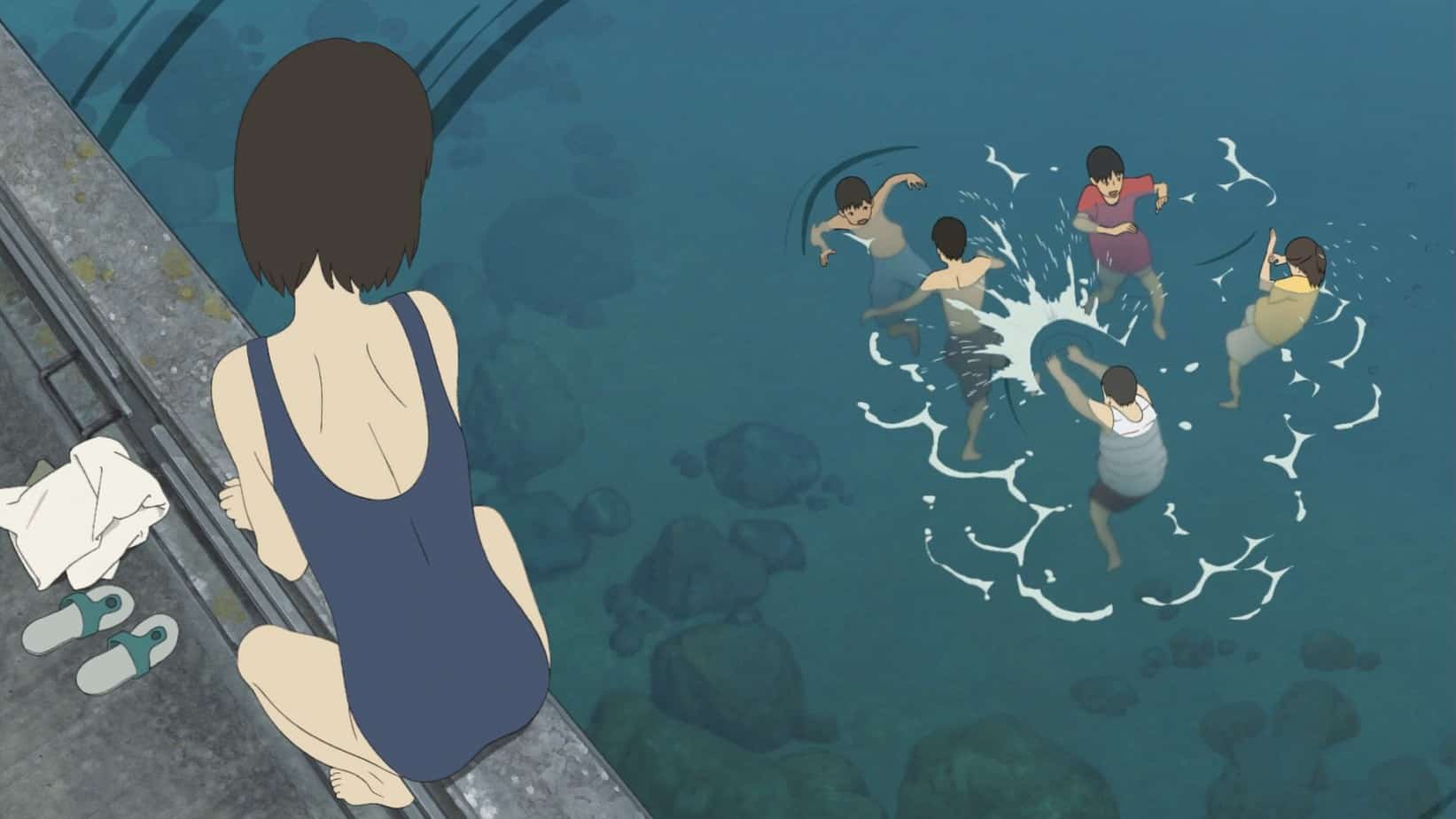

Why has the character for evening tide been chosen for the name of this village, instead of the character for morning tide? It could have gone either way because Momo is young and is starting a new life, but if you stayed for the roll of credits you’ll have noticed the pillow shots of the slow, elderly nature of the island. This is a village which is dying, devoid of young people. It’s likely those children jumping off the bridge are the only children in the village. Will Momo build an entire life here? I doubt it. I imagine Momo returns to the mainland for her upper education. In fact, I just checked my watch and it’s already 2018, so she’s probably there now.

More on the Symbolism of Islands in storytelling.

Buddhist Culture In Letter To Momo

If you ask young Japanese people on the street about religion, you get something like this:

In Japan you can consider yourself Buddhist without any of the mystical beliefs of yore, just so long as you have a ‘butsudan’ (a Buddhist altar) in your house (or in your parents’ house, probably), and participate in the Bon Festival. You can see a Buddhist altar in this movie. Mother and daughter stand in front of it and think about the dead father. There’s a photo of him hanging there. My host father was the most interested in my host family’s altar — he’d take a small portion of food in there each night for his dead ancestors. The following night he’d bring out the crusty old rice and replace with new. The altar is basically a place where you go to think about loved ones — a convenient little grave right inside your own home. (It’s not where the actual dead bodies are kept.)

At the height of summer, Japanese people have Obon.

Obon (お盆) or just Bon (盆) is a Japanese Buddhist custom to honour the spirits of one’s ancestors. This Buddhist-Confucian custom has evolved into a family reunion holiday during which people return to ancestral family places and visit and clean their ancestors’ graves, and when the spirits of ancestors are supposed to revisit the household altars. It has been celebrated in Japan for more than 500 years and traditionally includes a dance, known as Bon-Odori.

Wikipedia

The lantern tradition is a great spectacle, and the only part of Obon depicted in Letter To Momo:

Tōrō nagashi (灯籠流し) is a Japanese ceremony in which participants float paper lanterns down a river; tōrō is a word for “lantern,” while nagashi means “cruise” or “flow.” This activity is traditionally performed on the final evening of the Bon Festival in the belief that it will help to guide the souls of the departed to the spirit world.

Wikipedia

What must it be like, to really believe that your dead ancestors are visiting Earth again each year? In A Letter To Momo, the idea that the world is inhabited by a parallel realm of live creatures harks back to an earlier time where people really did believe in the supernatural. Dead souls were (are?) thought to hang about for a bit before going to ‘up there’, a belief which helps the grieving process.

Japanese Culture In Letter To Momo

You’ll notice some specifically Japanese body language in this anime. Here’s Momo in the middle of a big, exaggerated march. This is a girl on a mission. This is a particularly juvenile kind of walk, emphasising youth. I wonder if it comes from the fact that Japanese school children used to do a lot of marching. (There’s still ‘marching music’ played in many Japanese schools at cleaning time.)

Something the animators of this film do extremely well is the body language of Momo (and Mame). Momo doesn’t just sit on the tatami mats — she pushes herself around on them while lying down, propelled forward by her feet.

There are numerous other examples of a girl behaving how kids really behave when they’re not confined to a chair, and it’s not something I’ve seen a studio like Pixar do particularly well. The kids in Pixar films — compared to this one — behave like little adults. Is that because our Western way of making kids sit on chairs and sleep on raised beds prevents them from being kids? In any case, the childlike body language of Momo when she is bored and at home in her Japanese-style house is especially realistic. I believe any child would behave like this in the same setting.

Momo’s mother beckons to her in a typically Japanese way, calling her over to meet the elderly relatives. When I first got to Japan I thought my host-mother was shooing me away when she did this.

You’ll see Koichi the postman point at his face to mean ‘me’, whereas Westerners tend to point to our chests, as if our ‘selves’ reside in our hearts rather than in our heads.

Shoes are removed in the entrance nooks (genkan), and although it’s polite and ‘correct’ to turn your shoes around to face the door when you step out of them, most kids don’t. We see Yota step into his shoes backwards, shuffling backwards out the front door in a comic-realistic fashion. These are kids being kids, without the parental intervention.

Bicycles and mopeds are a great way of getting around narrow and winding roads such as these, because utility vehicles and cars would need to back up when meeting an oncoming vehicle.

Is there a rule that umbrellas make an appearance in every Japanese anime? I shouldn’t be surprised really, since umbrella culture is strong in Japan. With a heavy and predictable rainy season, in which rain is usually unaccompanied by wind, making them genuinely useful, there is usually a point in a Japanese film when rain is utilised as pathetic fallacy. Here, too, a rainstorm not only functions as an impediment to the characters getting what they want (a doctor for the mother), but also stands in for Momo’s emotions. Rain = tears, thunder and lightning = uncontrollable and strong feelings.

Japanese Folklore In A Letter To Momo

The ‘goblins’ who appear to Momo are known as ‘yookai’ (with the long ‘o’ sound) in Japanese. The class of yokai is much wider than the subtitles translation of ‘goblin’.

Yōkai (妖怪, ghost, phantom, strange apparition) are a class of supernatural monsters, spirits and demons in Japanese folklore. The word yōkai is made up of the kanji for “bewitching; attractive; calamity”; and “spectre; apparition; mystery; suspicious”.

Wikipedia

Though historically yokai didn’t look like anything in particular, their forms started to solidify in the collective Japanese imagination once artists started sketching their own imaginings onto emaki (horizontal, illustrated narratives created during the 11th to 16th centuries).

The yokai featuring in A Letter To Momo:

- Iwa no ke — Spirit of Rocks. This guy looks scary at first because he can’t close his massive mouth. But when he is revealed to be harmless, his permanently open maw makes him look easily duped and comical. Rocks are associated with masculinity in Japanese culture. Therefore he is depicted as big and strong. An evil version of this guy can bite your head off, as Kawa points out. Like Grizz of the We Bare Bears, Iwa is the guy who takes the lead, even when his ideas are terrible.

- Kawa no ke — Spirit of Rivers. This guy is particularly grotesque, with stinky big farts being one of his superpowers. An evil version of Kawa can suck your soul out through your mouth, as he comically demonstrates on Kawa. Evil river spirts can also cause drowning. But in other traditional stories they just fart, for some reason. (You’d think this would be more heavily associated with wind, wouldn’t you?) Kawa hates anything that requires effort, and speaks with the dialect favoured by hoodlums who’d like to fancy themselves Yakuza.

- Mame no ke — Spirit of Beans. This little guy is harmless and innocent, like a toddler. He is shown to be friendly with all the spirits on the island, which comes in handy later. Beans are associated with smallness in Japanese language, and ‘mame’ is also a homophone for honest, devoted, hardworking and active. Of the three yokai here, Mame is the airhead who does things at his own pace. He doesn’t always hang around with the other two, having his own friendly friends.

The idea that there’s a spirit in everything is a Shinto idea rather than a Buddhist one. (Is Shintoism a ‘religion’? A Japanese lecturer at university was a stickler about this — I got marked down in an essay for Shintoism a religion. I’m still bitter.)

Another film — one from Hayao Miyazaki — Princess Mononoke, is all about the spirit of things. In fact, that’s what mononoke means: the spirit of things. If you’ve already seen that anime you’ll recognise the nymphs of the forest. (Kodama)

STORY STRUCTURE OF A LETTER TO MOMO

This story spans the time between learning of the father’s death at sea and his final departure to the world of the dead, though the plot begins with Momo arriving at her new home, and flashes back to fill in the parts when they lived in Tokyo, including the two main parts relevant to her recovery:

- The argument she had with her father

- The phone call she overheard when her mother learned of his death

The argument is presented twice, once with a medium angle camera, the other view from further away. The first time we don’t know what the argument is about, so the exact details of it are used later as a reveal.

Whenever a plot begins with a child starting in a new place, there will be flashbacks. The story usually starts a bit earlier. There’s a reason why people move and in stories it’s often pretty grim.

PARATEXT

Taglines:

- When I really started to notice, I wasn’t alone. (Used in the poster below)

- Dear Momo; An unfinished letter from her father is left behind.

- A wonderful encounter.

- They had a “mission”.

- Are you telling your loved ones what truly matters?

- Words that were never said.To save those you love.

- A letter that ties the bond between them.

SHORTCOMING

Eleven-year-old Momo is the viewpoint character, the main part of the story, and also the character who undergoes the main character arc, making Momo unambiguously the main character. You’ve probably noticed that Japanese directors aren’t afraid to make feature films for everyone starring girls. There’s a reason for this which isn’t feminist in origin — these girl characters have flaws but are ultimately a version of the Female Maturity Formula. While Momo has her faults, the little mother in her makes her the voice of reason, persuading the male-gendered yokai characters to behave themselves, going to great lengths to stop them from stealing vegetables from the villagers. Upholding the moral fabric of a community is more often considered a feminine job. The yokai make stereotyped reference to ‘women’ numerous times in the dialogue, which is what genders them male in a more-than-symbolic way.

Momo’s ‘ghost‘ is that she has lost her father. We are not told this right away. As is usual, this ghost is withheld as a reveal.

Momo needs to move on from her father’s death and forgive herself.

The problem is, her father is dead, and the last time she saw him she told him to go away and never come back. Now she can’t take those words back.

Her shortcoming is that she can be ‘wagamama’, as Japanese people might put it. Selfish, inward looking. The mother is presented non-empathetically to the audience, but this is because we are seeing her through Momo’s eyes. Momo does not see her mother cry, and nor do we. We only see the mother leave each day for her nursing seminars, leaving her daughter with the basics but alone nonetheless, told to amuse herself with homework. Japanese children do get a lot of homework over summer, but Momo is between schools. She has little motivation to do it.

DESIRE

Momo is a reluctant participant in this new life, wanting only to return to Tokyo. But the mother has said that she sold the house in Tokyo rather than rent it out, so we know this is not an option.

Momo’s ‘below the surface’ desire is to be part of a team, to have friends. Her mother’s clumsy attempt at making friends for her is embarrassing to her. She needs to make genuine friendships alone.

OPPONENT

Momo’s main opponent is ultimately herself — her own conscience — she can’t forgive herself for those careless words she threw at her father. But in a narrative ‘oneself’ makes for a really boring story. Therefore, we have fully embodied opponents which represent the very things Momo doesn’t like about herself. In this supernatural tale them come to her in the form of the yokai.

These yokai are initially very scary, especially for young children. But as soon as Momo works out the nature of them they morph into comedic characters more reminiscent of ribald Japanese humour, resplendent with farts and nose-picking and hairy butt cheeks. They are quite grotesque. Momo, too, thinks of herself as grotesque after yelling at her dad. These yokai are self-absorbed, shown by their never-ending appetites and inability to give a damn about whose food they are stealing.

Momo’s human opponent is also her mother, standing in the way of just packing up and moving back to Tokyo.

At first the twelve-year-old boy looks like he may turn into a romantic opponent, and other directors would have made the most of this possibility but as it happens these kids are allowed to be kids. At eleven years old Momo is pre-adolescent, which is a less usual age for main characters. Main characters tend to be twelve. Twelve-year-olds are on the cusp of adulthood, but also in English language they are about to hit the ‘teen’ years. This makes me wonder for the first time — is there something about the Japanese way of counting which makes twelve-years-of-age not so special? When counting beyond ten in Japanese it goes ‘ten-one, ten-two, ten-three, ten-four…’. There’s no phonological change after twelve. The concept of ‘teenager’ comes from English, as does the Japanese loanword, ‘tiineejaa’. Is our Western concept of twelve as ‘the end of childhood’ down to the words we use for numbers?

PLAN

Momo’s plan that sustains the middle part of the film is ‘To prevent the yokai from stealing the village vegetables’. This all changes when Ikuko has her asthma attack — now the plan is dire and simple — Momo must get medical help during a terrible storm in order to save her mother’s life, otherwise she’ll be left an orphan.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle phase of A Letter To Momo reminds me of the one in Hud, but only in one sense: A physical tousle is followed by a war of words. These lead into a ‘life or death’ struggle. In Hud, Hud tries to rape Alma. In A Letter To Momo, Momo’s mother almost dies of asthma.

By the way, my asthmatic husband says the depiction of asthma in this film is better than in most, though asthma attacks don’t tend to be accompanied by coughing. This massive asthma attack is foreshadowed by two events:

- The old man is told not to smoke by his wife, because the old woman knows it sets off Ikuko’s asthma.

- Ikuko is drinking tea and it goes down the wrong way. This coughing and spluttering fit is probably why the animators thought it necessary to make Ikuko cough during the asthma attack.

Here’s what’s left off the screen: Ikuko’s getting the doctor. Instead there is a cut from the stormy scene with all the supernatural creatures banding together to save Momo’s mother, right to the next morning, with the mother lying in bed. From that high angle, at first it’s a possibility that she is dead. So that’s one good reason to cut. The other is that there would be no ironic potential in a doctor’s scene, and every scene needs some level of irony. At the doctor’s, Ikuko would be treated for her asthma. We don’t need to see that because it goes exactly as we expect it would.

ANAGNORISIS

As mentioned above, one of the taglines transliterated from ‘catch copy’ in Japanese is:

気がつけば、私、ひとりじゃなかった。

When I really started to notice, I wasn’t alone.

Momo’s big anagnorisis happens in between big struggle scenes. Before rushing out to cross the bridge Momo realises that her mother has been badly affected by her father’s death. This is prompted by the old woman saying that Ikuko’s suppression of emotion has contributed to her failing health. All this time Momo has been wallowing in her own pity. She is lonely all day and doesn’t want to be here where she has no friends, her mother won’t believe they’re surrounded by supernatural creatures that only she can see… Yet Ikuko has her own inner world that Momo cannot see — Ikuko has lost a husband just as much as Momo has lost a father.

At first the film makes us think that by ‘not alone’ Momo means the yokai. Which also works. But really, more deeply and more symbolically, Momo is not alone because she and her mother are going through the same grief. Hence, the deeper meaning of the catch copy.

The second part of the anagnorisis happens when Momo reads the letter from her dead father, sent back on the lantern boat. This is the mother’s anagnorisis, too. She’s had nothing to do with the yokai, but this time she allows herself to believe that her dead husband has a kind message from beyond the grave.

By the way, the English version of the catch copy asks us, “Are you telling your loved ones what really matters?” Which speaks to an interesting cultural difference. Westerners value “I love yous” and other grand gestures of love expressed towards those closest to us, but Japanese families are traditionally laconic in this regard, preferring to let gestures of love speak for themselves. This may be changing with globalisation.

NEW SITUATION

Momo plucks up the courage to jump into the sea from the bridge — all so symbolic it almost hurts.

Mother and daughter will always have each other. As they stand together on the beach we know that their relationship will improve from now on. The yokai are no longer needed, so they have departed with the rest of the dead souls at Obon.

CHARACTERISATION OF MOMO

A number of reviewers have something like this to say about the character of Momo:

Momo’s displays of emotion belie an otherwise flat characterisation. Despite the amount of time spent with her, both in and out of flashbacks, she never becomes a truly compelling or inspiring protagonist, as nearly all of the Miyazaki heroines do. Considering that she is in some serious psychological pain, it’s not totally surprising that Momo spends at least half of the film with her shoulders slumped and head down; it’s just a bit disappointing that she rarely reveals herself to be more than what she appears on the surface, exhibiting a plot arc more than a full-fledged personality.

Film Comment

And I’m not sure why. Could it be that English-speaking reviewers can’t connect to an eleven-year-old Japanese girl? Now that I’ve analysed the structure it’s nothing to do with that. Momo’s inability to express her feelings may make her a little distant to a Western audience, but I suspect a native Japanese audience intuitively grasps what she would be feeling inside, and identify with her civic-mindedness regarding saving the community vegetables.