Callous and Unemotional Traits

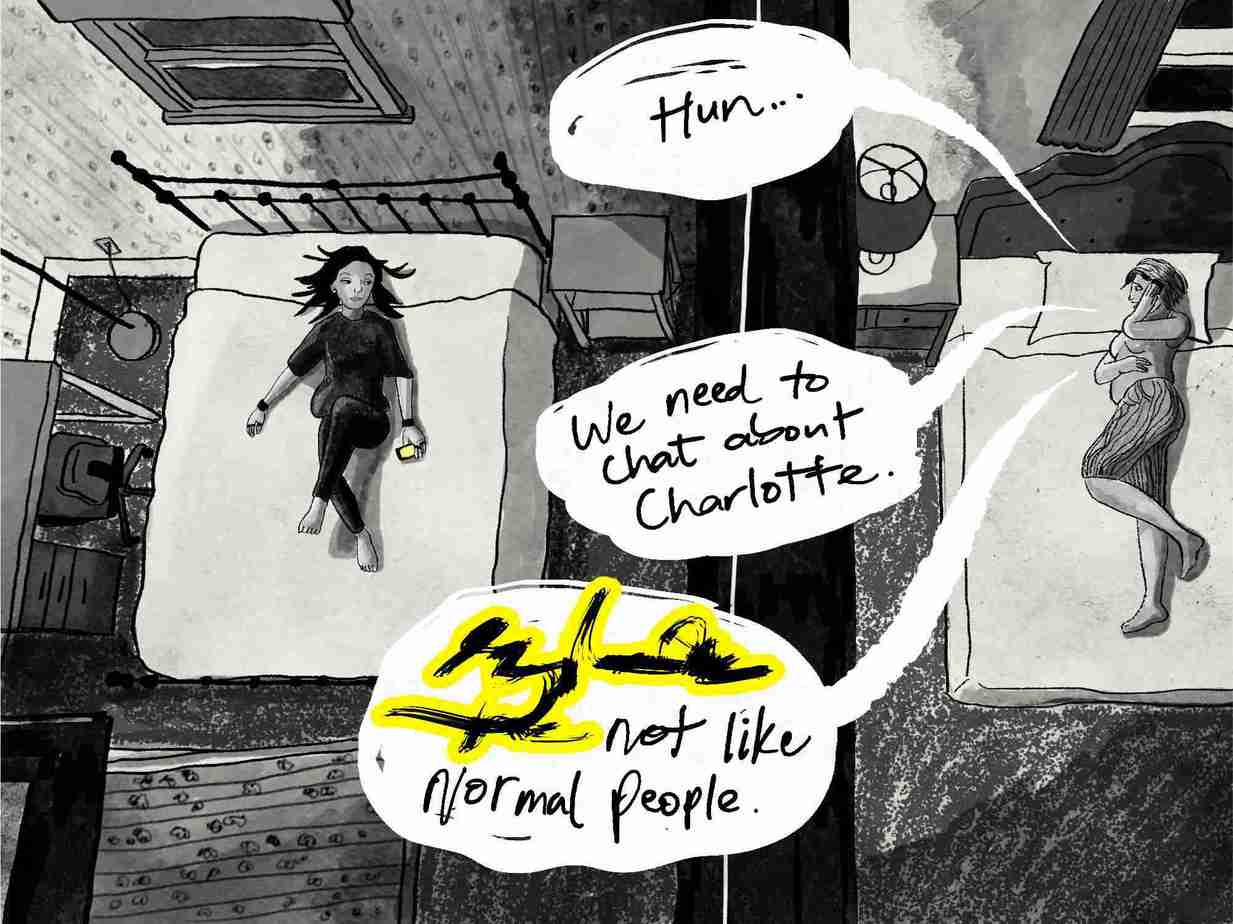

After Charlie’s psychologist talked to her mum, Charlie overheard her mum leaking Charlie’s private business over the phone.

“Hun,” Michelle began. ‘Hun’ meant Lionel, Charlie’s dad.

Michelle had shut herself inside her own bedroom, but Charlie heard everything from the other side of the wall.

“Are you sitting down, hun? Because we need to chat about Charlotte.”

That made Charlie’s ears prick up. Her mother was using her unshortened name, Charlotte — not Charlie. Must be serious.

It was November now, and after a trying winter Charlie’s parents were mostly communicating by phone. After the separation Michelle bought the unit in Upper Hutt. Ironically, now that Lionel and Michelle lived forty minutes apart, Charlie heard everything going on between her parents. She didn’t even need to press her ear to a flap of mouldering wallpaper. The plasterboard between the two bedrooms offered no auditory privacy. At Roseneath in Wellington she had her own wing, on a whole different floor, in a refurbished house with double glazed windows and insulation. Michelle wasn’t used to keeping her voice down.

Charlie was obviously filling in some blanks but apparently the psychologist told Michelle that her daughter “lacks affective empathy”. By the worried tones coming through that wall, Charlie figured this was a Bad Thing.

Affective empathy? Charlie was about to search it up on her phone, but her father didn’t know the term either. So Michelle explained to him, as well as to Charlie.

“She has an abundance of cognitive empathy… can read emotions fine… just doesn’t feel things like normal people.”

Not like ‘normal people’. Isn’t that a spectacular thing to hear about yourself?

“No hun,” Michelle continued, “no one said ‘psychopath’.”

A pause. Charlie imagined her parents both on freeze frame.

“That’s not a label they pin onto kids.”

Another lengthy lacuna. So Charlie was not a psychopath yet.

Regardless of what the psychologist actually said, Charlie’s own parents were kicking around with the word. This was a Thing they were Actually Discussing, like it was a future possibility.

Charlie could name a number of psychos: Cruella de Vil, Hannibal Lecter, the guy off Psycho. How could her parents lump her in with those outright villains? She hadn’t even done much.

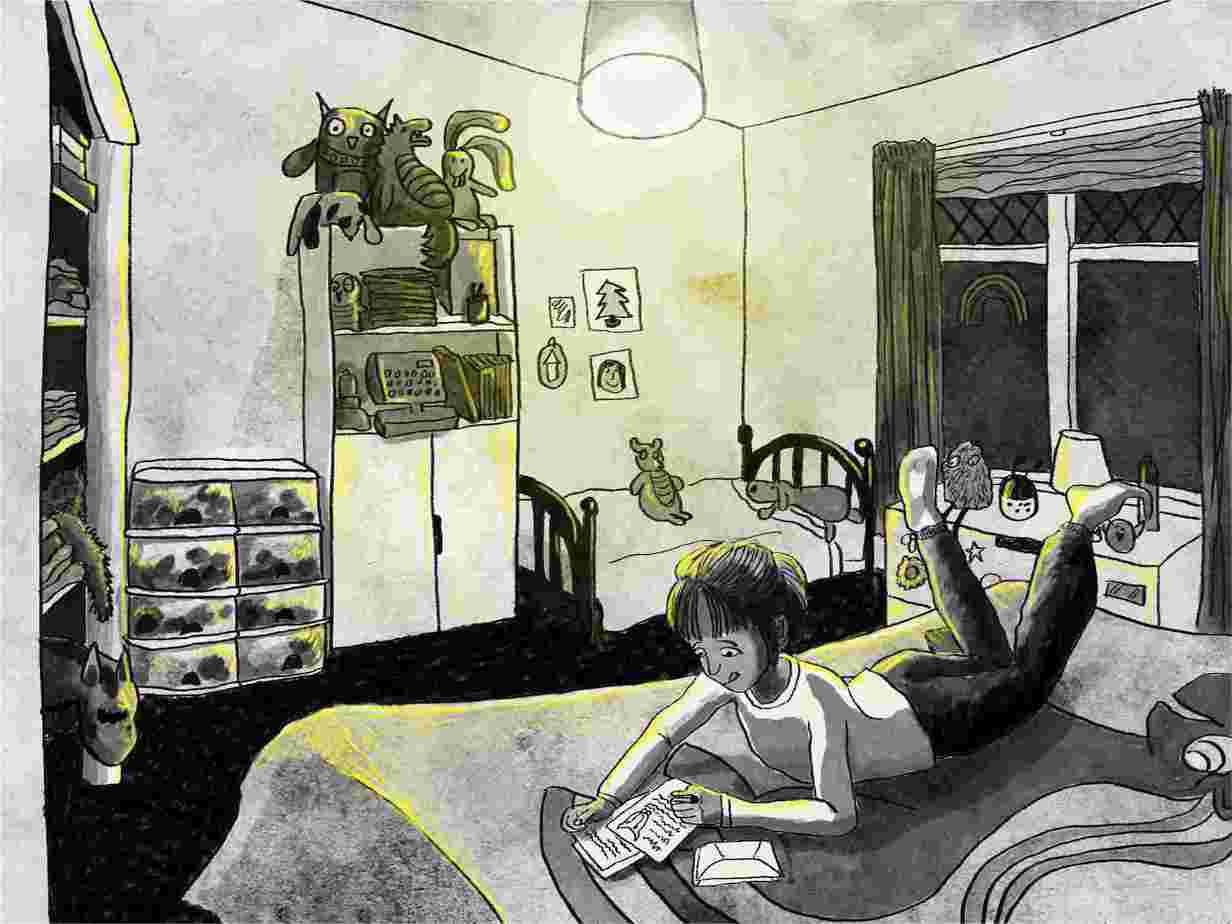

Next, Charlie did what anyone else would do. She lit up her phone and proceeded to doomscroll through pages and pages of info about psychopaths. She learned that Hannibal Lecter off Silence of the Lambs is written like a supernatural creature invented for fiction, not a realistic portrait of a psychopath at all. She learned some extra new words.

‘Idiopathic’. Those are the dangerous category of psychos.

‘Covert’. Those ones fly under the radar. Those kind are probably everywhere.

Charlie sat upright in bed.

The Internet led her to a forum populated by self-disclosing psychopaths who wouldn’t have it any other way.

‘Just because you’re a psychopath doesn’t mean you have to do bad shit. I’m psycho as they come, and I’m pretty darn nice to people. Why spew more hatred into this evil world?’

That’s when Charlie experienced a Joycean epiphany: If not a full, diagnosable psychopath, she must be one granny step away.

Psychopath, psychopath. She tested the word out loud. She imagined it on a t-shirt. On a bumper sticker. On medical records. She imagined the looks she would get if people knew she was a psycho. She’d pick her moments, of course. The more she thought about this, the more she liked the idea.

She stood up on the mattress. She emitted a triumphant whoop. With her dark hair haloed by the naked bulb aglow on the ceiling, she really might pass for some kind of movie villain.

Michelle, easily startled right now, flung open her daughter’s bedroom door. No knock or nothing. Rude.

“Um, are you okay?”

Aiming for mysterious and cryptic, Charlie addressed her mother as if addressing an audience. “Is anyone ever really… truly… okay, mother dearest?”

Charlie lay awake til 3 a.m. reading the entire Internet. She had a hunch you’re not meant to self-diagnose via Reddit threads, but everything made sense, doc.

As it happens, Charlie had been called a ‘psycho’ plenty of times before. Yeah, sure, everyone throws that word around these days. It doesn’t mean jack. But when applied to her, it came in a clenched whisper. Sometimes nothing was voiced, but she still sensed that word, lodged behind the teeth, caught in the throat.

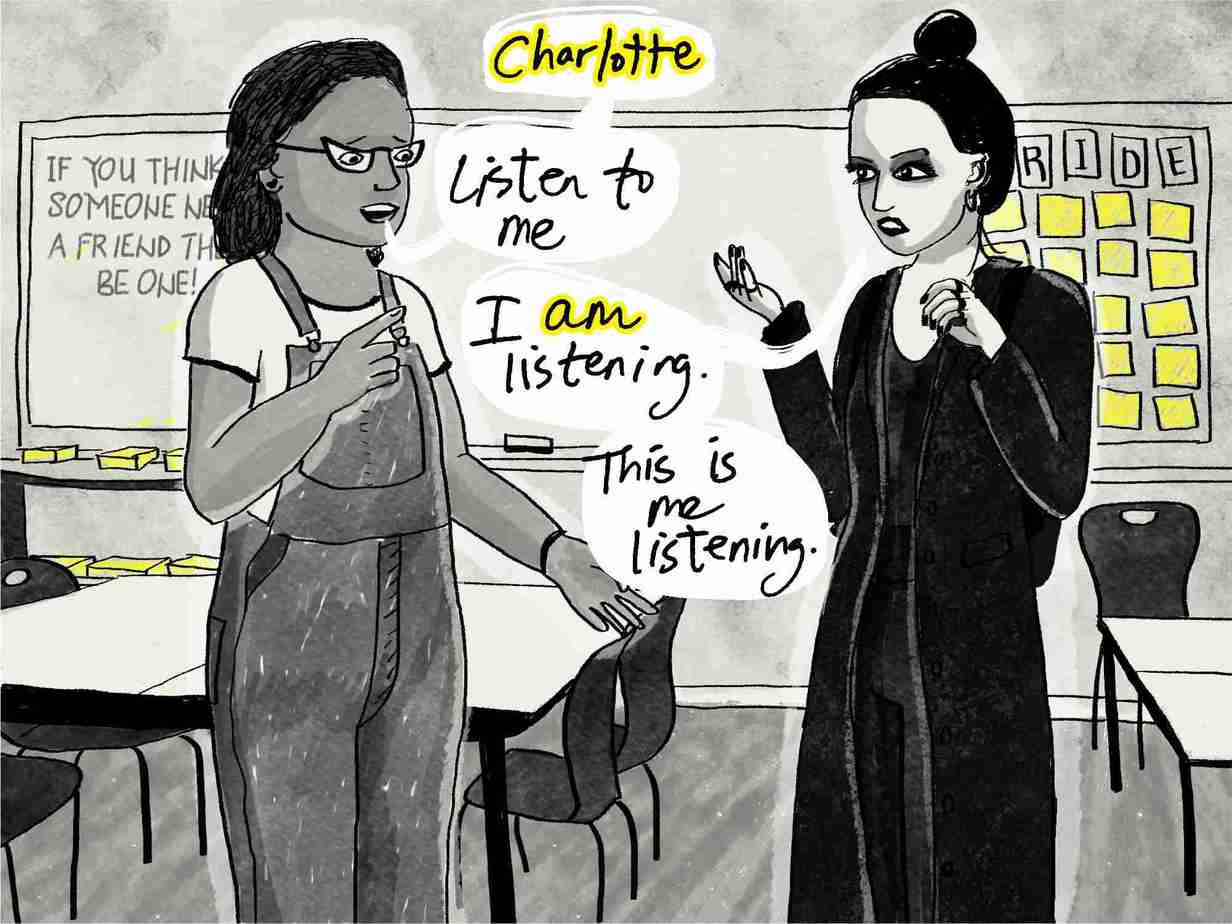

They might go, “Charlotte, that’s messed up.”

It was never ‘Charlie’. There’s the tell. People would switch to ‘Charlotte’ when she scared them. The dark eyes, a hasty departure.

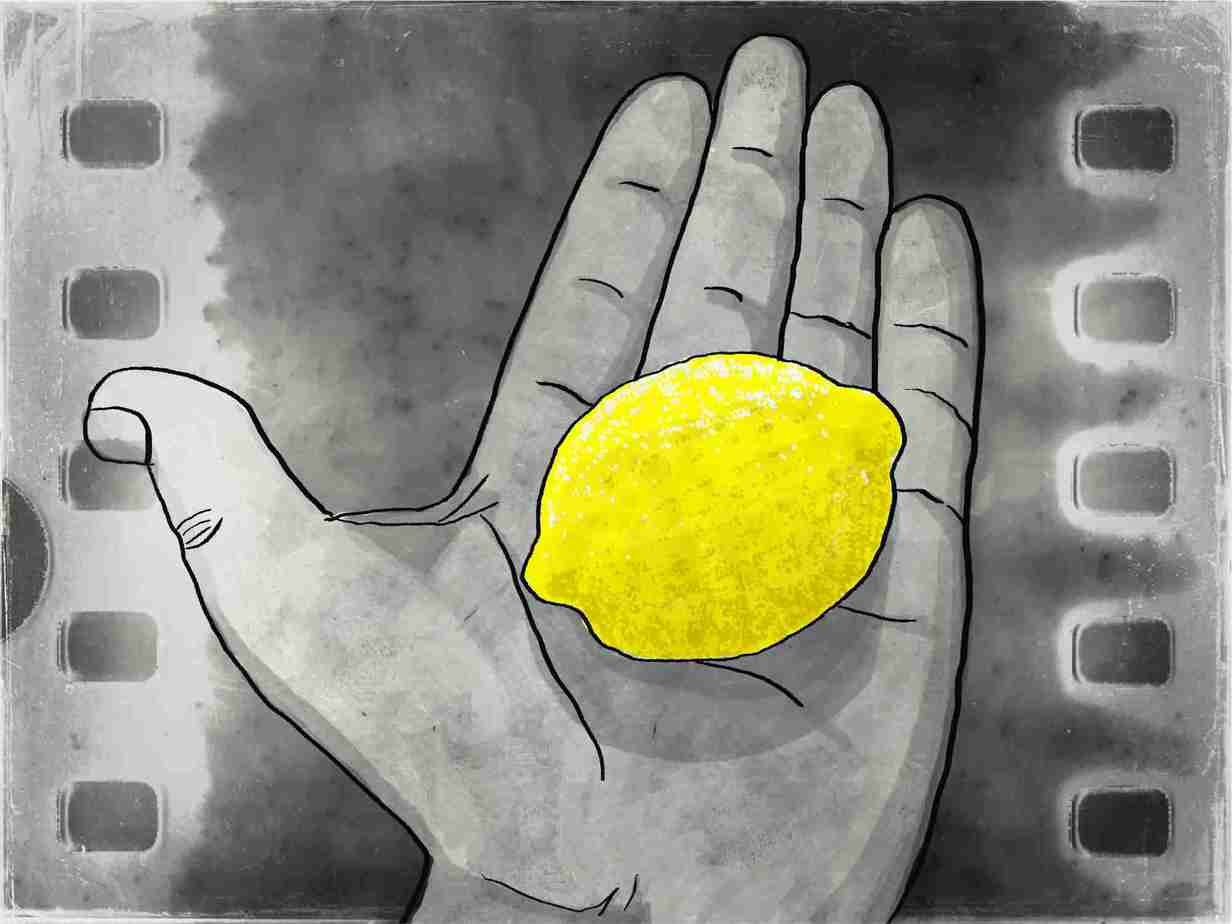

Charlie sometimes did dumb stuff for kicks. Like, she did pick all those baby lemons off Michelle’s fruit tree. That’s why her mother called the shrink for an update. That row of fruit trees out back was the one thing Michelle liked about this tumbledown shack. “We’ll make jams in the summer,” she said when she gave Charlie her first underwhelming look-round. “And homemade lemonade!”

“I’m okay with 7UP out of a can, to be honest.” That’s all Charlie said.

Pretty much the only redeeming feature of this old dump, over-hyped by the real estate agent, were those well-established fruit trees. So naturally, Charlie’s failure to enthuse about the possibility of homemade lemonade hurt her mother’s feelings. And that is precisely why ‘feelings’ are a nuisance.

A stupid thing like that. Then, last week, Michelle found a handful of shrivelled up lemon babies in Charlie’s pocket. She yelled at Charlie from the washing machine, which was now in the kitchen, near the back door.

“Have you been plucking baby lemons off my tree?” she exclaimed in her cry-voice. Charlie noted the change in terminology. It was ‘her’ tree now. Not ‘ours’.

Michelle didn’t even need to yell. Charlie was standing right next to the stove. She was stirring a saucepan of macaroni cheese, but Michelle made Charlie turn round and “lookit”.

The little green lemons had fallen out of Charlie’s pocket and were rolling around on the kitchen floor. Those ones were from an early plucking. Charlie likes babies the best.

“Oh, Charlie! What on earth are my dear little lemons doing, zipped inside your coat? What the hell is wrong with you?”

The million dollar question.

Charlie knew how upset she had made her mother. Michelle had assumed some weirdass lemon-lovin bird got into them, but now she knew the truth and her cheeks flushed pink.

Now Michelle is looking at Charlie like her own daughter is a stranger in her kitchen. Charlie expects Michelle to accuse her of the usual, how she’s ‘insensitive’ and ‘callous’ and ‘thoughtless’ and ‘unfathomable’.

But Charlie did not pick those lemons out of spite. She wasn’t even thinking about her mother’s feelings. This lemon thing all started because Charlie enjoys better self-control when she carts a few of them round in her pocket. Whenever she’s bored at school, which is often, she plunges her hand into her pocket and digs her fingernails into the skin. The flesh of young lemons is pleasantly unforgiving. Certain classmates make a nuisance of themselves whenever they get bored, subverting lesson plans, harassing teachers. As far as boredom prevention strategies go, Charlie’s is harmless. Harmless except to the lemons, of course, who also lack affective empathy, or any empathy at all, because they are LEMONS.

No one needs to notify the authorities because, baby lemons aside, Charlie hasn’t killed anyone. She doesn’t need to go on some government watch list. She’s not some proto-criminal waiting to pounce. She’s not even a pulling-the-legs-off-spiders, squeezing-the-breath-outta-kittens-for-kicks kind of psycho. That’d be pointless. Why would she bother doing that? Charlie actually enjoys the company of spiders in the house. She considers them decorative. And kittens don’t annoy her.

Let’s see who annoys her, though.

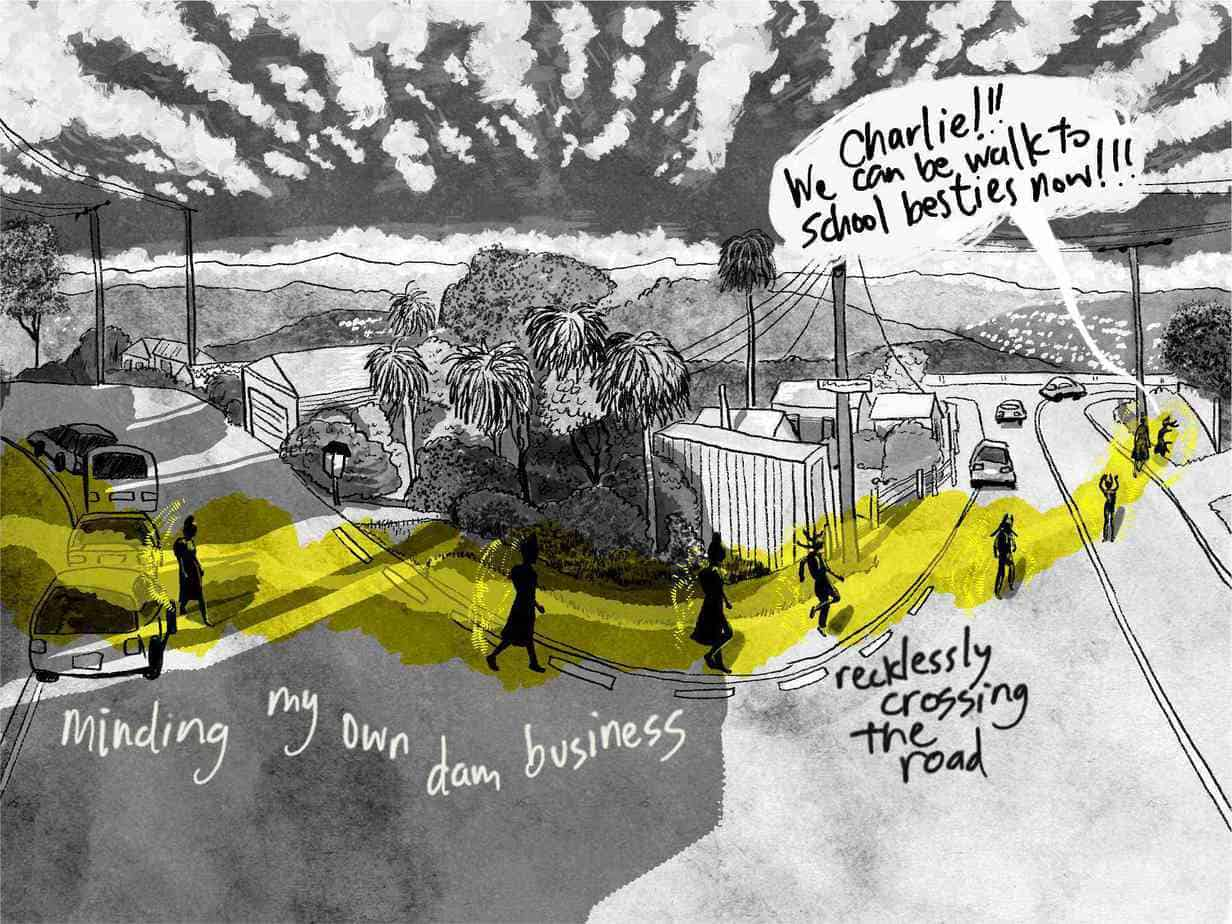

New Girl

Peppy Willow Jensen. Human version of a hangnail.

This is in June, right after Charlie’s parents made the split. Not two days settled in at Lionel’s fresh digs, Charlie’s minding her own business, eating toast on her new walk to school, when who rushes up from behind and slaps her hard on the backpack? Willow Jensen: Charlie’s best friend’s annoying-ass other friend. Charlie had avoided her the day before by sleeping in and arriving late to school. Charlie doesn’t care about externally imposed start times. You get there when you get there. Anyway, the beginning of any lesson is always the same old crap. But teachers are on power trips, and they send your parents notifications on their phones if you’re late, and then Mr Lionel Evaristo gets a phone call at work. So on her second day at his new villa, Lionel badgers Charlie out of bed and turfs her out his front door at some ungodly hour.

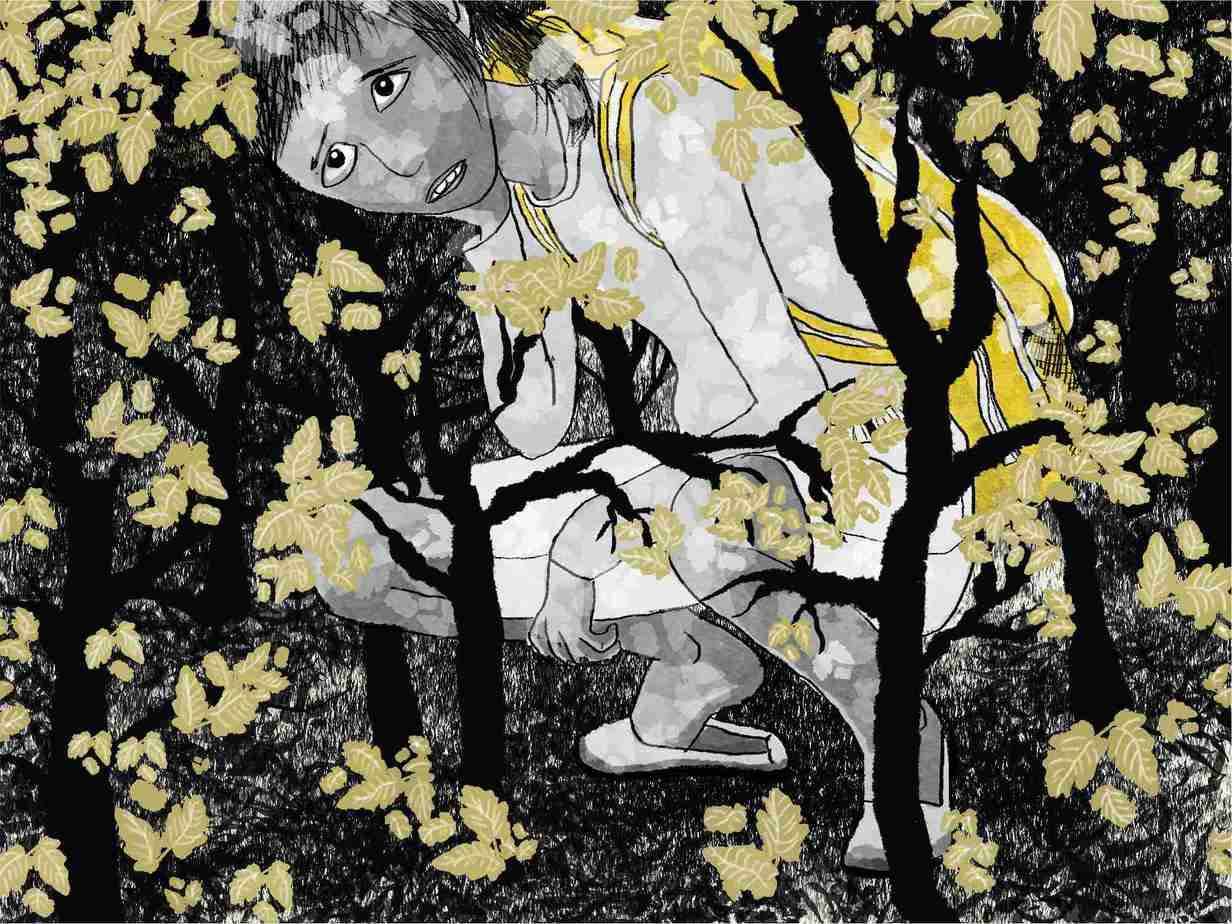

Willow Jensen is the naturally early type. Charlie notices her up ahead and hangs back. Unfortunately she’s the sort of person who never grew out of hopping and skipping and balance-beaming along ledges with arms outstretched. She launches off someone’s garden border with a gymnast’s twirl, the star of her own imaginary show. Then, when she’s standing in the middle of the road, oblivious to oncoming traffic, she sees Charlie coming up behind.

“Charlieeee!” Her eyes are big and her cheeks are pink from the wind. “Scarlett told me you’re a Mornington chick now!”

“Yup.”

Scarlett warned Charlie about Willow, except she didn’t mean it as a warning. Scarlett is stoked that Willow and Charlie can walk to school together. Scarlett wants to ‘triangulate’. She wants them all to be besties together.

“I worry about Willow,” Scarlett told Charlie one lunchtime, between mouthfuls of leafy green salad. Lucky for Charlie, Willow makes herself busy at lunchtimes helping out at the canteen or weeding at garden club, otherwise she’d be hanging round them two like sandflies on a tramping trip.

“Willow is so… exuberant.” Scarlett never says a bad word about anybody, though her condescension betrays her Niceness™️. “I doubt that girl looks both ways when crossing the road. Keep an eye on her, okay?”

Charlie must be doing her job because Willow is walking way too close to her right now, matching her stride, even with her short little legs.

“So,” Willow says, meaningfully. “Scarlett told me about your dad. Just for the record, that topic doesn’t have to be off-limits or anything. I’m a liberal.” Willow has lowered her voice, and Charlie could swear the kid has arranged her pixie face to look mournful. Everyone wears some kind of mask. “That must have been a shock for you,” she continues, because that’s what you’re meant to say. Then, “How’s your mother coping?”

“Fine.”

“Did she always suspect?”

“Suspect what, now?”

“You know. Did she always get a gay vibe?” But Willow is immediately disgusted with herself. “Sorry,” she says. “Personal question. I forget you’re not Scarlett. Charlotte, Scarlett. I guess I just mix you both up!”

“Dad’s not gay,” Charlie says. “He’s bi.”

“Oh no!” Willow covers her mouth with both mittens. “I’m so sorry! Hashtag mortified!”

At first Charlie thinks she’s mocking her. But she’s genuine, all right. As genuine as Willow gets. She spends the next ten minutes apologising. Apologies do nothing for Charlie. (The diagnosing psychologist can go ahead and add that to the little checklist thing.)

“Standard bi erasure!” Willow groans. Charlie detects Scarlett’s influence. Scarlett is in Feminist Club.

“I can’t believe I just did that! Please don’t tell him I did that! He’ll hate me! I’d hate me!”

“Trust me, I won’t.” Charlie doesn’t need Lionel and Michelle getting chummy with Willow Jensen. She’ll show Charlie up with that relentlessly upbeat vibe of hers. Also, Charlie prefers to forget about Willow Jensen entirely when she’s not in Charlie’s actual face.

Charlie did have some fun with Willow when Willow first moved down to Wellington. Charlie would say something clearly sarcastic, clearly bullshit, and Willow would go, “Oh no! That’s terrible, Charlie!” Then Charlie realised Willow believed every damn thing she joked about and she wasn’t fun anymore. Willow is too easy. The juice ain’t worth the squeeze.

For Charlie, at least, it’s a very long three kilometre walk to school.

The walk is slightly improved though, after Corey Brasher catches up to them. Corey Brasher is the biggest fool in school, and competition is stiff for that title. Charlie didn’t realise Brasher lives in Mornington, too. He rushes up behind Willow and yanks her massive backpack. She almost falls backwards into his arms, which is clearly what he wants. Willow’s too busy blathering on to Charlie about an English assignment to notice him sneak up. Then Corey Brasher tries to engage Willow in chit-chat about her weekend but she’s not having it.

He clearly likes her.

But Willow is too dumb to know it, because after he lopes on ahead she tells Charlie he’s a pain in the neck and she’s not talking to him anymore. She tells Charlie he left something in her letterbox.

Now Charlie’s a little interested. “Like a love letter?”

Willow looks disgusted. “As if.” Then she examines Charlie’s face. “Oh. Are you being ironic again? Okay, yes then. It was a ‘love letter’.” She even does the air quotes with her fingers, or attempts them through her mittens.

Charlie would like to know more about Corey Brasher and what he put in her letterbox. But she won’t tell Charlie. This is unlike Willow. Clammed-up Willow is slightly more interesting than Blathering-on Willow.

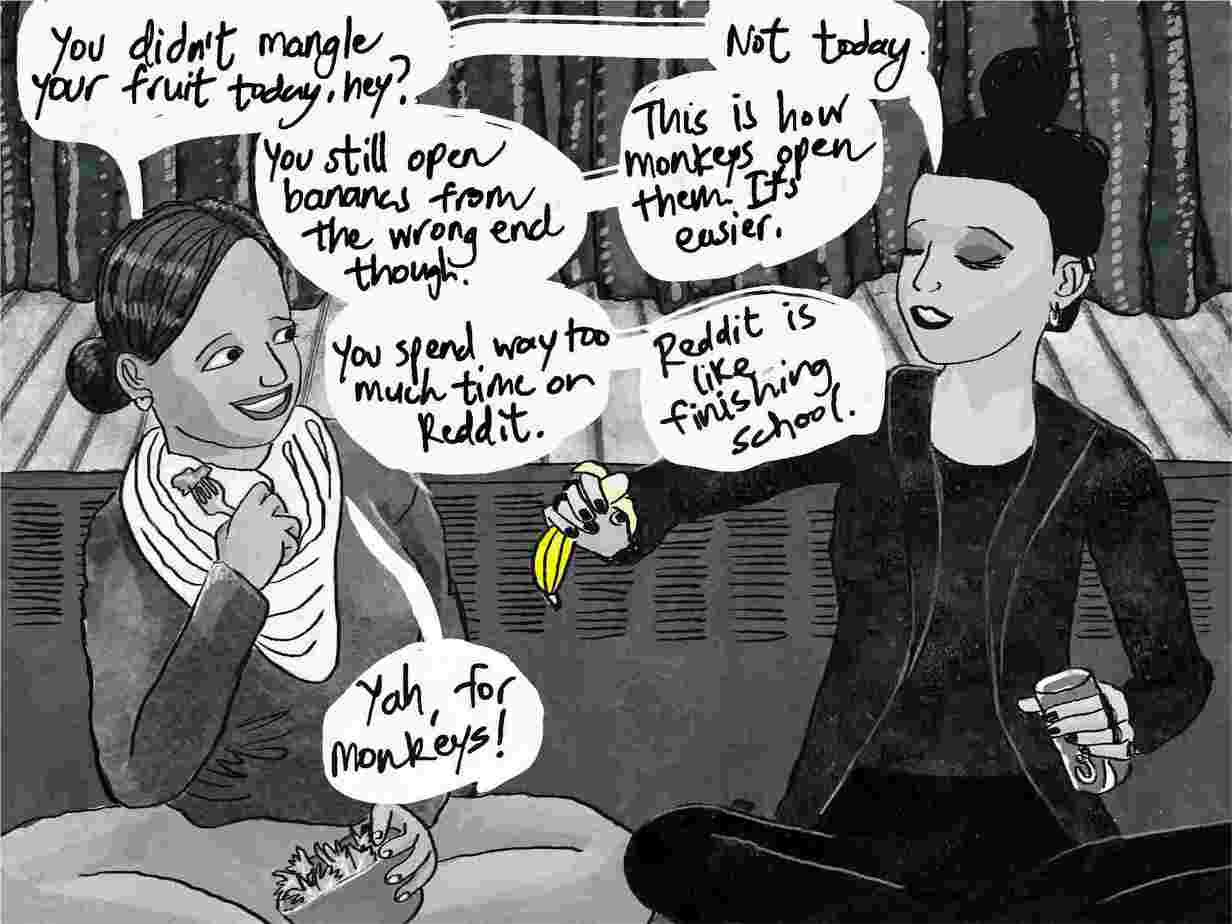

If Charlie really wants to know what Corey Brasher put in Willow Jensen’s letterbox she’ll ask their mutual friend Scarlett. At lunchtimes she and Scarlett normally find a heater and shit talk, and although Scarlett says she doesn’t like to gossip, like everyone else, she’s easily drawn into it. Charlie’s trick is to segue in, starting with chat about inconsequential crap.

Eventually Scarlett tells Charlie Corey Brasher put a lemon in Willow’s letterbox. That’s it. That’s the story.

“You mean an actual lemon? As in, fruit? This isn’t code for something?”

“Nope. Yeah, a fruit lemon. A big yellow lemony lemon.”

“How do you know it was Corey?” Charlie asks.

Scarlett, who only thinks she knows everything about everyone, gives Charlie a withering look. “He walks past her house twice per day.”

After last class Charlie ducks out of school before Willow gloms on. She wears her headphones and doesn’t look back.

Charlie and Corey Brasher have more in common than Charlie realised. That’s disturbing. Charlie happens to be carrying lemons of her own, but not big yellow Pak n’Save ones like Corey Brasher’s, so there’s that.

Charlie carries little green baby lemons from her mother’s precious tree. She doesn’t always carry fruit, but when she does, it’s lemons. Wasn’t always lemons. She went through a carrot phase. Then apples. She used to mutilate the apples from her lunchbox. But now she’s old enough to avoid messes and sticky fingers. These days she chooses a cleaner sensory toy.

It’s raining hard but she’s already soaked to the skin, so instead of going straight back to Lionel’s she walks the extra half k to reach Willow’s house. One shivering hand reaches into her coat pocket and fishes out a little lemon baby. She’s been caressing it all day, digging her fingernails into its skin. But Willow can have it now. She checks behind her first. Next she checks Willow’s front window for movement. No one is home to see this happen. So Charlie takes a baby lemon and gifts it to Willow Jensen, through the Jensen family letterbox.

Charlie doesn’t know why she’s like this.

The Lemon Gag

Let’s clarify. Charlie doesn’t know what made her slot that first little lemon through Willow Jensen’s letterbox, except that she happened to have some on her and Brasher proved unlikely inspiration. But she does understand the link between Willow and lemons in general. Unlike Willow herself, Charlie is not a gullible naif.

The lemon gag started over a year ago, term one of year nine. This had nothing to do with Charlie and her baby pocket lemons, which no one at school even knows about. Charlie wasn’t even in the vicinity when this all went down.

Basically, Willow started high school a year later, in year ten. The Jensens moved down from Hamilton in January. Their year level all kind of knew each other by then, but Willow knew no one.

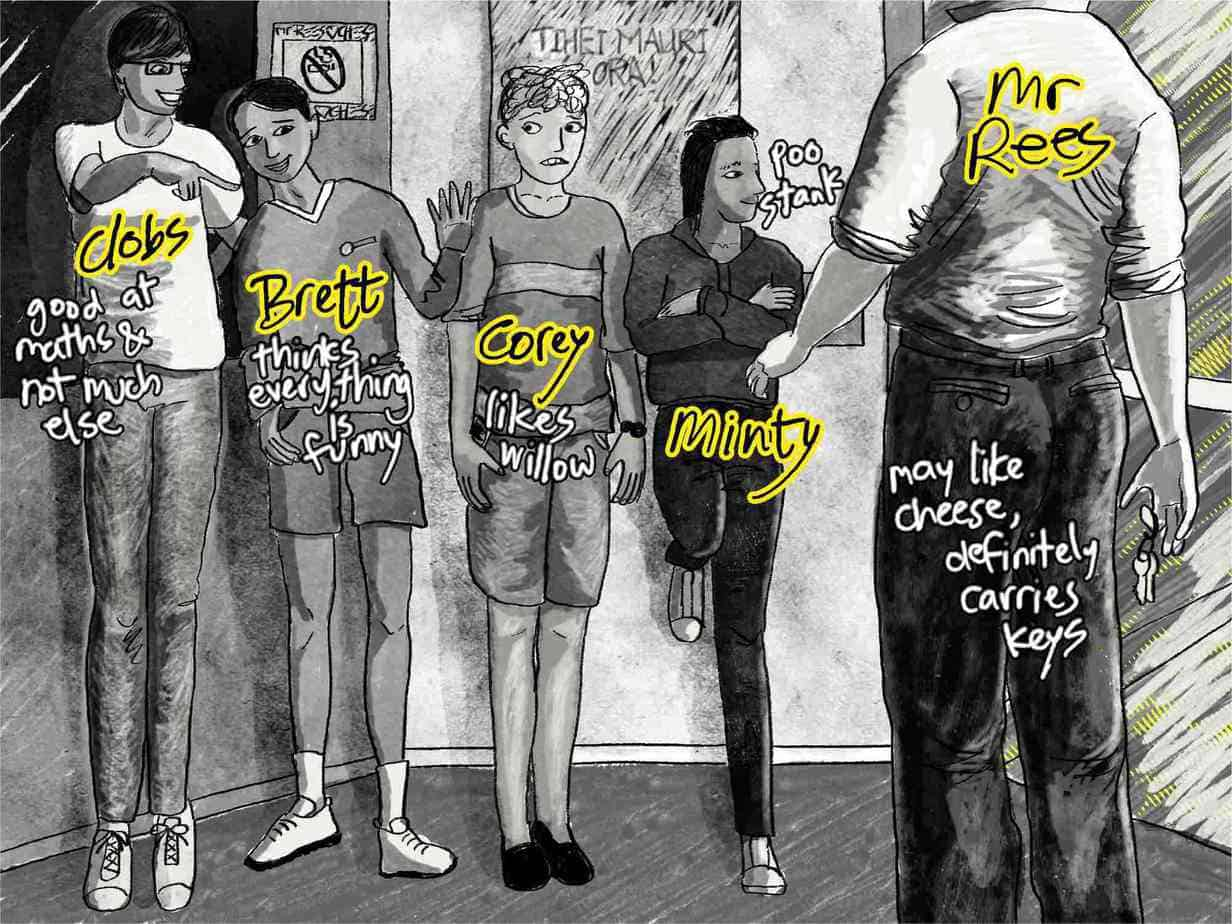

Corey Brasher, Brett Aaldenberg, Clobs McCraig and a stank-breath guy called Minty stole a whiteboard marker from science but actually lost their lunch hour for being irresponsible with Bunsen burners. They’re waiting in the admin foyer for a lecture on expected behaviour when the dumbest of the lot is struck by another genius idea. He scribbles ‘Mr Rees Loves Cheese’ around the border of the laminated smokefree signage. Mr Rees emerges from the staffroom right at that moment and gets way more cranky than any of them expected.

“Corey Brasher.”

Corey points at Clobs. “It was him.”

“You’ve got green ink all over your fingers, boy. And is that my good whiteboard marker, sticking out of your pocket?”

This is all second-hand info to Charlie, but she knew that’d make them snigger. Their sniggers always make Mr Rees more angry, as does evasive mumbling, a Cheese Boy speciality. Their science teacher is what Charlie calls ‘an easy wind-up’.

Mr Rees goes on and on about ‘graffiti’, even though it was only whiteboard marker, not permanent, and wiped right off on Corey Brasher’s sleeve.

Corey knew he’d better own up to the idea, to the stolen marker, to everything, but Mr Rees had heard way too much about cheese already that term. Those guys were always talking about cheese on toast. He gave all four dickheads rubbish duty, and yes, they may use disposable gloves, but only if they’re not going to be stupid with them. (They were stupid with them.)

So far this story’s got nothing to do with lemons, except Willow Jensen finished phone duty just as Mr Rees was concluding his rant. She volunteers at the office on Tuesdays so the receptionist can catch a lunch break, and also because her friends need a break from her. She must sense this. Anyway, right at the deadliest moment of silence, she chimes in.

“Our grounds will be super tidy when you boys are finished!”

Oh, god.

And then, to make matters worse, she busts out with the kind of meme your nana posts on Facebook. “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade!”

After that, Corey Brasher and his mates stopped making cheese jokes and started making lemon jokes. Willow realise this for ages, but every time they talked about lemons, they were really talking about her.

Whenever Willow volunteered an answer in social studies one of them would mutter, “Easy peasy, lemon squeezey!”

If Willow offered to troubleshoot someone’s computer one of the Cheese Boys would go, “I feel like lemon-aid.”

‘Sour’ became their catchall term for anything bad.

If Willow told someone to stop talking over the teacher they’d go, “Ooo, someone’s got the pip.”

Charlie sits near the front in English, and that’s where Miss Berry makes the Cheese Boys sit, too. She needs to keep a constant eye on those guys. Their jokes are not funny in and of themselves, but Charlie enjoys the stern looks Miss Berry shoots them whenever they make lemon puns.

They’re not puns in the true sense. They’re not even clever. They just substitute regular words with ‘lemon’. Sometimes ‘lemon’ means nothing at all.

“Hey, Minty, can I get a loan of a lemon? I brung nothing to write with.”

“Miss, can you tell Brett not to touch my lemon? He keeps touching it.”

“Hey Miss Berry, Clobs is leaning back on his lemon. He’s gonna fall off it and lemon himself badly, miss.”

But then, whenever Willow speaks up in class, or does a presentation, or volunteers for a task, the lemon jokes blow back on Willow. Sometimes ‘lemons’ refer to Willow’s boobs. That’s distasteful. Charlie never approved of that. Charlie does have some respect for other people’s feelings even if she thinks their feelings are bullshit. She must do, because she’s always trying not to laugh. She’s good at not laughing, too. Unlike the Cheese Boys, she’s learned to laugh on the inside.

Anyway, now Charlie knows for sure, it’s not just her with the Willow-cringe. Those Cheese Boys confirmed it for Charlie. Willow Jensen was annoying as hell.

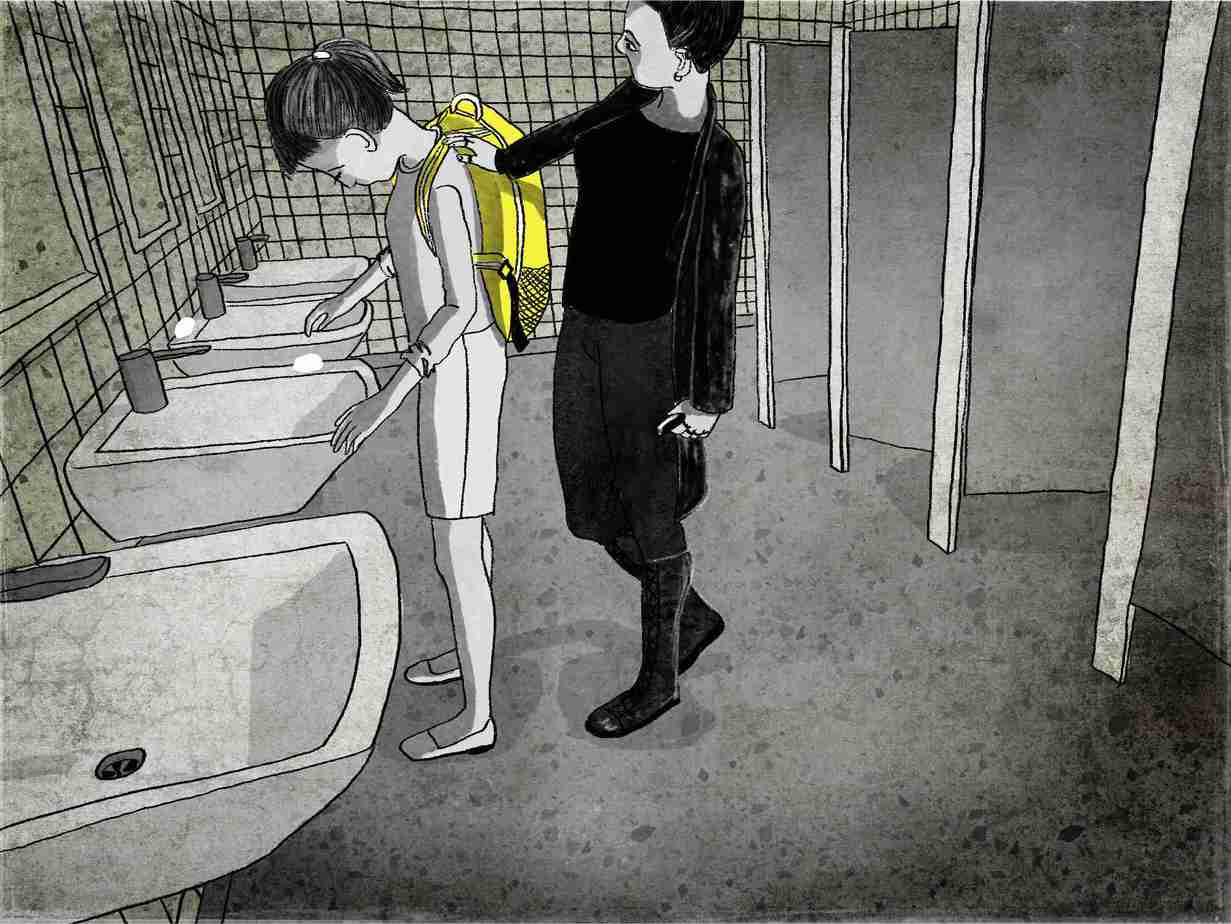

Willow’s First Day

Charlie got the measure of Willow on their first full school day of term one. Charlie ditched science class to visit the toilet, where she sat for a long while locked inside a stall because she didn’t need to hear Mr Rees going on for a full hour about safety in the lab. They’d heard the same thing this time last year.

Enjoying her peace and quiet, scrolling through Reddit threads on her phone, Charlie was surprised to hear someone else had decided to entertain themselves in the girls’ bathroom during class, but by washing their hands over and over, all the while sniffling.

The person at the basin must be using a wasteful amount of soap. Charlie flushed the toilet and emerged from the stall to see who it was.

It was her. This kid was the only new year ten who looked like she wanted attention for being new. This impossibly short girl with distinctive front teeth wore a massive yellow back pack, and she’d brought it with her into the toilet, which meant she hadn’t gone to class first. Someone must have given her grief over it already.

The girl let out a single sob.

Any other girl in year ten, without exception, would have said, “Hey, are you okay?”

But Charlie decided to prod a little. “Cool back pack,” she said, sarcastically bright. “Is it brand spanking new?”

“Oh! Thank you.” The girl seemed grateful for any attention at all. Charlie had unwittingly subsided the sobs for her.

Then the girl wouldn’t stop talking. “My grandma gave it to me for Christmas back home in Hamilton. It came with a matching lunchbox and a matching pencil case, but the pencil case is too small. It doesn’t fit my longest pencils inside, until they’ve been sharpened, like, ten times…”

Charlie now understood she was dealing with a certain brand of nutter. Willow kept yakking. Mid-yak, Charlie escaped from the toilet block to rejoin science. The annoying chatty yellow kid followed close behind.

“Hey, I have to be… in class,” Charlie said, just as Mr Rees poked his head out of the classroom door. The lesson was almost over. He looked flustered.

“Ladies, aren’t you meant to be in my class right now?”

“Heavy clots,” Charlie replied neutrally.

Mr Rees stepped all the way outside his classroom door and clicked it closed, but only to attenuate his own embarrassment. Charlie couldn’t wait for his reproduction unit. She would have real fun with the guy then.

“Surely not both of you at once,” he mutters. Conveniently for Charlie, Mr Rees is bad with names, and his clipboard of mug shots never seemed to help him any. “Anyway, Scarlett, I see you’ve made friends with young Wendy, here. I trust you’ll make sure Wendy gets where she needs to be going today.”

‘Scarlett’ and ‘Wendy’ saw out the conclusion of science class, and by the looks on people’s faces, everyone in the lab had overheard the ‘heavy clots’ part. This satisfied Charlie, though probably didn’t do much for the new girl.

“My name is really Willow.” Charlie hates the feeling of warm whispers in her ear.

After the bell, Charlie (still going by ‘Scarlett’) says, “Aren’t willows meant to be tall, though?”

“You’re funny, Scarlett. Do you think we could be friends?”

Willow expects her new friend ‘Scarlett’ to show her the canteen and where to change for P.E.

By the time the real Scarlett encounters the pair of them, Charlie has already persuaded Willow to play ‘hide and seek’ as a campus orienting exercise, and has also ‘failed’ to find her.

That’s how Willow ends up spending her entire first lunchtime alone in a bush, but Charlie’s evil plan hasn’t worked to shake the kid, because the kid’s only gone and concluded that her hiding spot was super duper great.

Scarlett hears this and drops her jaw a little. “Charlotte Evaristo,” she says, with eyes darting between her closest friend and the new girl with the beacon for a back pack. “That is seriously messed up.”

Criminal Versatility

End of term three, Charlie gets roped into something terrible. Willow’s birthday sleepover. One morning in June, a full month in advance, Charlie’s on her way to school when Willow rushes up from behind and presents her with an envelope. The invitation is aggressively pink, hand-decorated in cartoon horses.

Hard to believe Willow turns fourteen a full month before Charlie does. Willow’s so damn excited about it, squeeing like a seven-year-old.

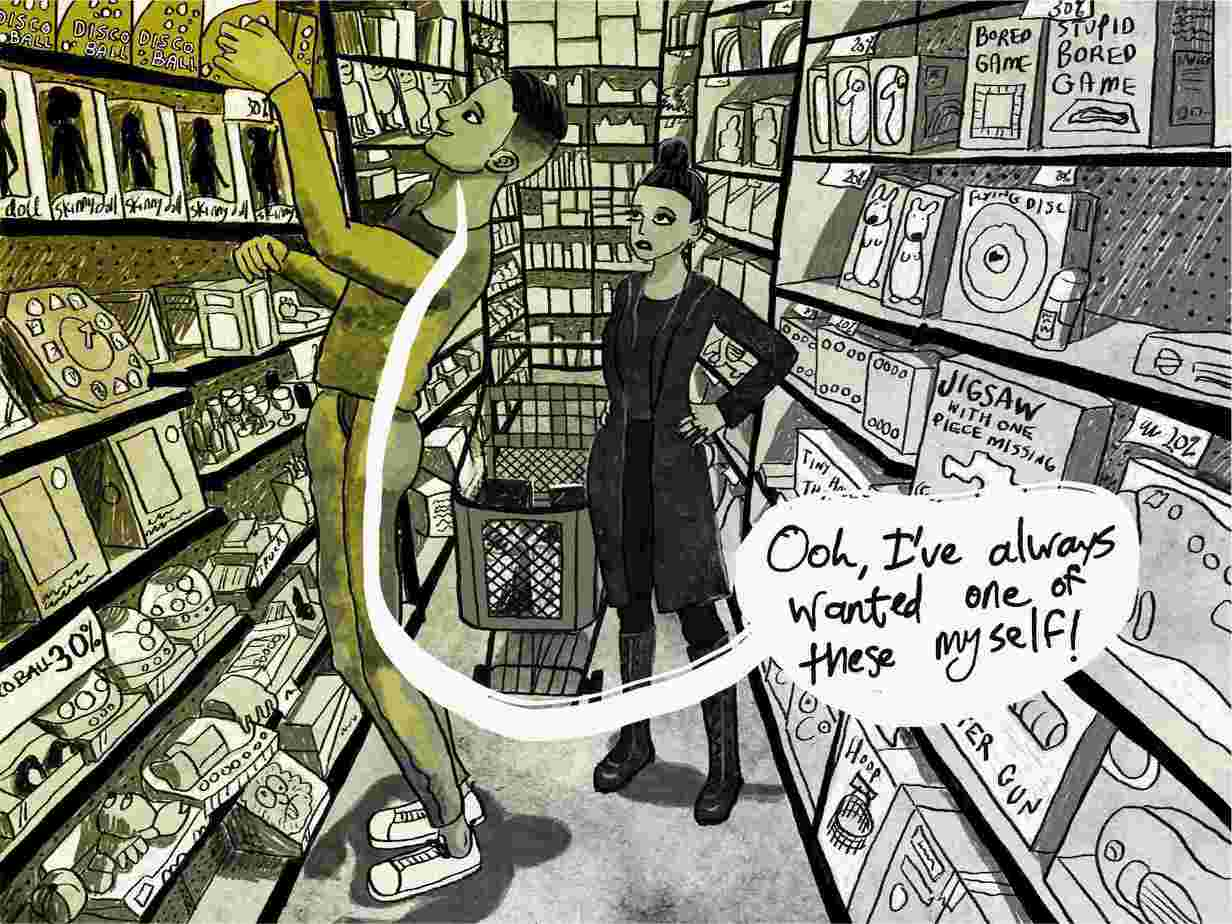

Lionel’s boyfriend Neil takes Charlie to buy the birthday present. Lionel asks why Charlie didn’t tell him earlier. He avoids brick and mortar stores and says they could’ve ordered something online.

Neil doesn’t mind shopping though. Charlie would way rather go places with Neil than with Lionel, anyhow. Neil takes her mountain biking, helps her with maths homework, and lately he’s teaching Charlie to serve at tennis. He’s clearly trying to forge a relationship with Lionel’s daughter to cement his relationship with Lionel. Charlie is required to spend quality time with her father as well, but Lionel’s got a bad back and doesn’t ever cave when Charlie asks him to take her through drive-thrus. So she’s fine with her parents’ separation, and she really means that. She’s only annoyed they all had to move out of their beautiful house in Roseneath. That part stinks. And then they made Charlie do therapy, like she’s the problem.

Lionel’s given Charlie two folded twenties to spend on Willow. It’s the Thursday evening before the sleepover and Neil’s driven Charlie to the shops after beef stir fry at Lionel’s.

So Neil and Charlie are wandering round The Ware Whare but she’s blanking out on gift ideas for Willow. There’s plenty Charlie could do with forty bucks for herself, though. Surely Lionel doesn’t mean for Charlie to spend it all on her.

“What sort of person is Willow?” Neil reminds Charlie they only have an hour before closing time.

“She’s flat out annoying,” Charlie tells him. “What do you buy for annoying people?”

“How about a cheap harmonica? Or a recorder. Perhaps a little chalkboard so she can run her nails up and down it for you?”

They laugh, but then Neil snaps to serious. “If you don’t like this girl, why are you pretending to be her friend? Isn’t that kind of… fake?”

Neil is a smart guy. He understands Charlie better than her own parents do, even though they’ve known each other for less than a year. He’s still got a ways to go, but he seems the kind of guy who’s had years of therapy himself.

Charlie often feels fake. She only pretends to care. It’s exhausting. It’s why she sleeps so much. But Charlie can honestly say that when it comes to Willow Jensen, she doesn’t have to fake it. Willow’s peppy enough for the both of them, and totally self-absorbed.

As evidence, Charlie never once did a single friendly thing to Willow. Except this. Charlie is attending her party to boost numbers.

“She’s only invited two people,” Charlie tells Neil. “Me and Scarlett. No one else gives her the time of day. But if she only asks Scarlett that’s like a regular hangout. You need three to make a ‘par-tay’.”

“Ah.” He seems good with this explanation. But he doesn’t respond how Charlie wanted him to. “In that case, let’s get Willow something she’d really love.”

Neil plays twenty questions about Willow’s areas of interest, and in the end Charlie lets him decide. Neil picks out a scarf with ponies on it, a three-pack of nail varnish to achieve a French manicure, a diary with a sparkly pen, and he can’t walk past the disco balls. They promise to light up a room. Willow’s probably scared of the dark, so that’s perfect, actually.

Neil says they should buy pretty wrapping paper, too, and a packet of cardboard tags, and a card with a grinning horse on the front.

“I can’t afford all that.”

Neil offers to put it on his credit card, since he chose it all.

“Fine. I’ll let you pay, but don’t tell Dad.”

He doesn’t. Charlie likes that about Neil. And now Charlie is up forty bucks, which she considers compensation for suffering through Willow Jensen’s sleepover.

The Sleepover

Charlie could come down with the flu and not go to this stupid overnight thing, except she’s kind of curious to see the inside of her house.

She can predict exactly how this sleepover’s going to pan out, but she wants to know she’s right.

She’s right. Except she didn’t predict Willow would also invite her seven-year-old bedazzled tutu-sporting sister into the fray. Turns out Mandy’s fully involved in her big sister’s birthday party, too. Great, Charlie thinks. An even smaller, even more annoying version of Willow. Because of Mandy they have to watch a G-rated movie but they probably would’ve anyhow because that film about the rat who can cook is Willow’s all-time fave. Mandy is not as annoying as Willow actually, because that would be impossible. She mostly just watches the movie without yapping because she’s busy eating Burger Rings off her fingers. Willow, on-brand as ever, shows off her memory for Pixar films by reciting lines right before the characters do.

Then Willow opens her gifts. Charlie would’ve ripped into them straight away, but not Willow. Willow reads cards first.

She reads Charlie’s out loud, with way more feeling than Charlie meant to convey on the page.

To Willow,

Happy Birthday

From Charlie.

She loves, loves, loves the grinning horse card that neighs when you open it, and she loves, loves, loves every single other piece of crap Neil chose from the tween section.

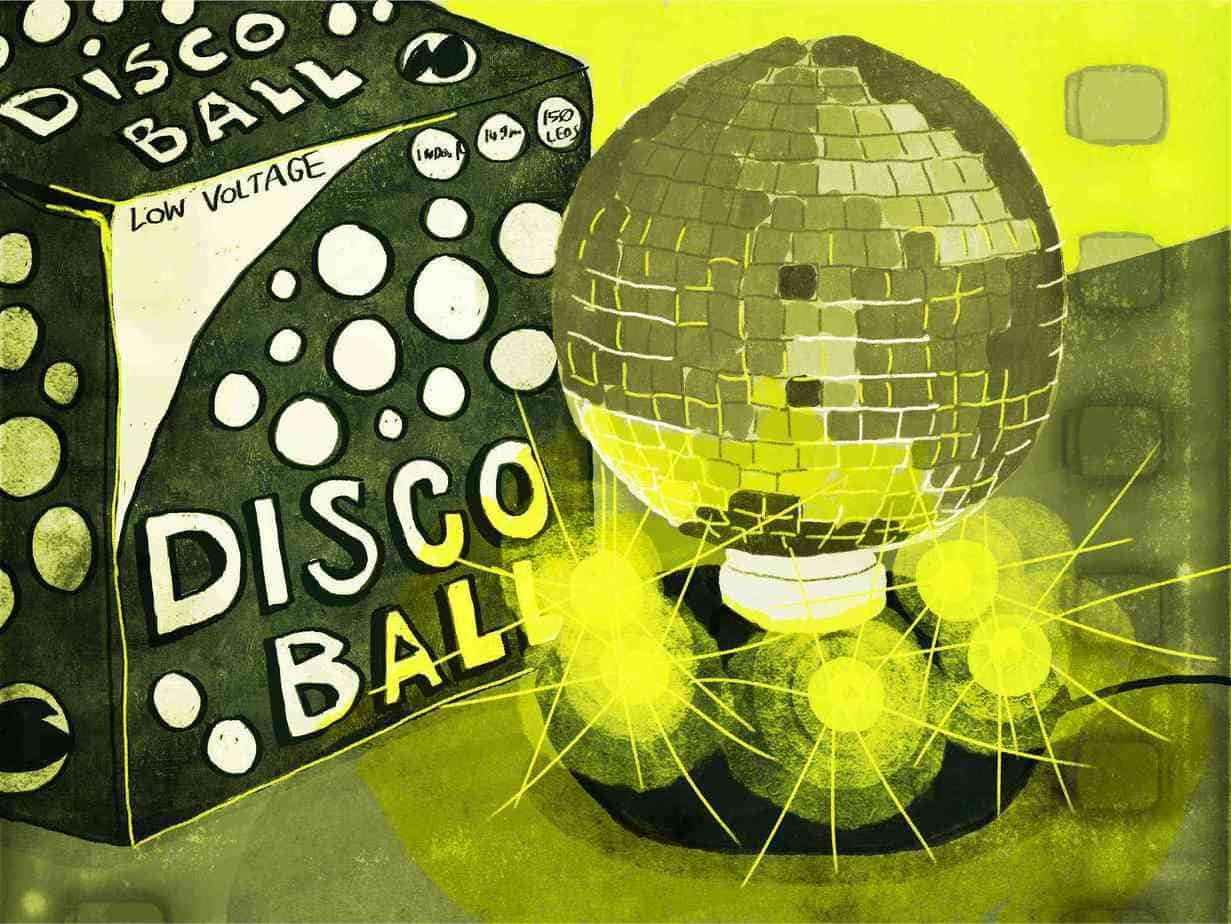

“A disco ball! Amazeballs!”

Charlie didn’t bother wrapping it all up in the pink horse paper because the stuff jammed together made a funny shape, and plus she didn’t know Willow was going to make a meal out of The Great Unboxing. But she did fold the plastic bag down neatly and slap a length of tape on it. Willow doesn’t mind that Charlie skimped on wrapping. She goes on and on about how great it all is. Charlie wants to tell her she didn’t have a single hand in choosing any of it, but that’d be mean. Why be mean to Willow?

Next, Scarlett looks shy about her own gift, which can’t have cost more than twenty bucks even though Scarlett Carter’s parents are rich as bastards. It’s a homemade bookmark inside the next volume of Willow’s favourite horse series. But Willow clutches the book to her chest and says she’d love to read it right away, all in one sitting, except that would be downright rude.

Willow’s main gift from her parents is a compact SLR camera. She takes heaps of pictures all night. Charlie offers to take them instead so she doesn’t have to be in them, but Willow asks Charlie if she knows how to adjust a manual lens. Charlie admits she’s a point-and-click photographer, so Willow won’t let Charlie touch her new precious camera.

Willow tells Charlie to smile. Charlie grimaces one out and they all assume she’s being funny, imitating that horse on the birthday card.

“Why didn’t you ask for a phone?” Charlie is genuinely curious. “Phones take decent enough pics, and then you get a phone as well.”

“This camera is as expensive as a smartphone,” Willow explains. “And my parents don’t think I need a phone just yet.”

“Why not?”

“I get a bit consumed by social media.”

Willow’s parents are right, actually. Imagine Willow with a phone. She’d be texting Charlie 24/7 with every basic thought that runs through her head.

Willow and Mandy have prepared a ‘show’. That USB disco ball sets the stage. They mime to the soundtrack of Frozen and leap about the family room. At least they only mimed it, Charlie thinks. Charlie can do without their off-key singing.

Willow’s dad tells the party-goers to clean up the living room because it’s time to pull out the mattress.

They arrange themselves for sleep in the living room. Willow insists on leaving that disco ball plugged in. Charlie was right about Willow and darkness — she’s bothered by it, all right.

Mandy has a bit of a sook because she has to sleep in the bedroom, separate from the big girls, and then the big girl confessions begin. This always happens at sleepovers. Anyone’d think there’s a rule about it. Darkness sets in, girls get deep with each other. Willow starts talking about her grandma, who is sick. Actually, it’s not even her grandmother. It’s her great-grandmother. What did she expect of a 98-year-old? Did she really expect the old lady to live on forever?

It’s Charlie’s idea to compete for the title of goriest storyteller but she’s all of three sentences in when Willow starts whimpering.

Then Charlie realises that wasn’t the best way to change a boring subject. Sometimes, especially in the dark, Charlie doesn’t have Scarlett’s face to glance at for reference. She forgets to say ‘the right thing’.

Willow thrashes out of her sleeping bag and melodramatically runs from the room.

Scarlett says, “Jesus, Charlotte,” and follows her.

They both return a few minutes later and Willow says she’s a little sensitive about her grandma and she doesn’t mean to be a bad host and ruin her own birthday party which has been super fun so far. Soon she’s laughing through tears, then she’s actually laughing, because Scarlett’s ‘ghost stories’ are a parody of genre and the opposite of scary.

Willow’s dad appears and says it’s 10:35. The girls had better get to sleep or else they’ll be ‘grumpy groaners’ tomorrow.

What’s a sleepover even for, if not for swapping freaky stories and low stakes confessions til the small hours? Charlie could escape from the Jensens’ right now, trot a few blocks in the dark and catch some comfy shut-eye in her own bed at Lionel’s. But she’s pretty sure Neil will be there overnight. He doesn’t stay over when Charlie’s hanging about. And that place is too small for a third wheel. By Charlie’s calculation, staying at Lionel’s is about as unpleasant as staying at Willow’s. So she puts up with the situation at Willow’s.

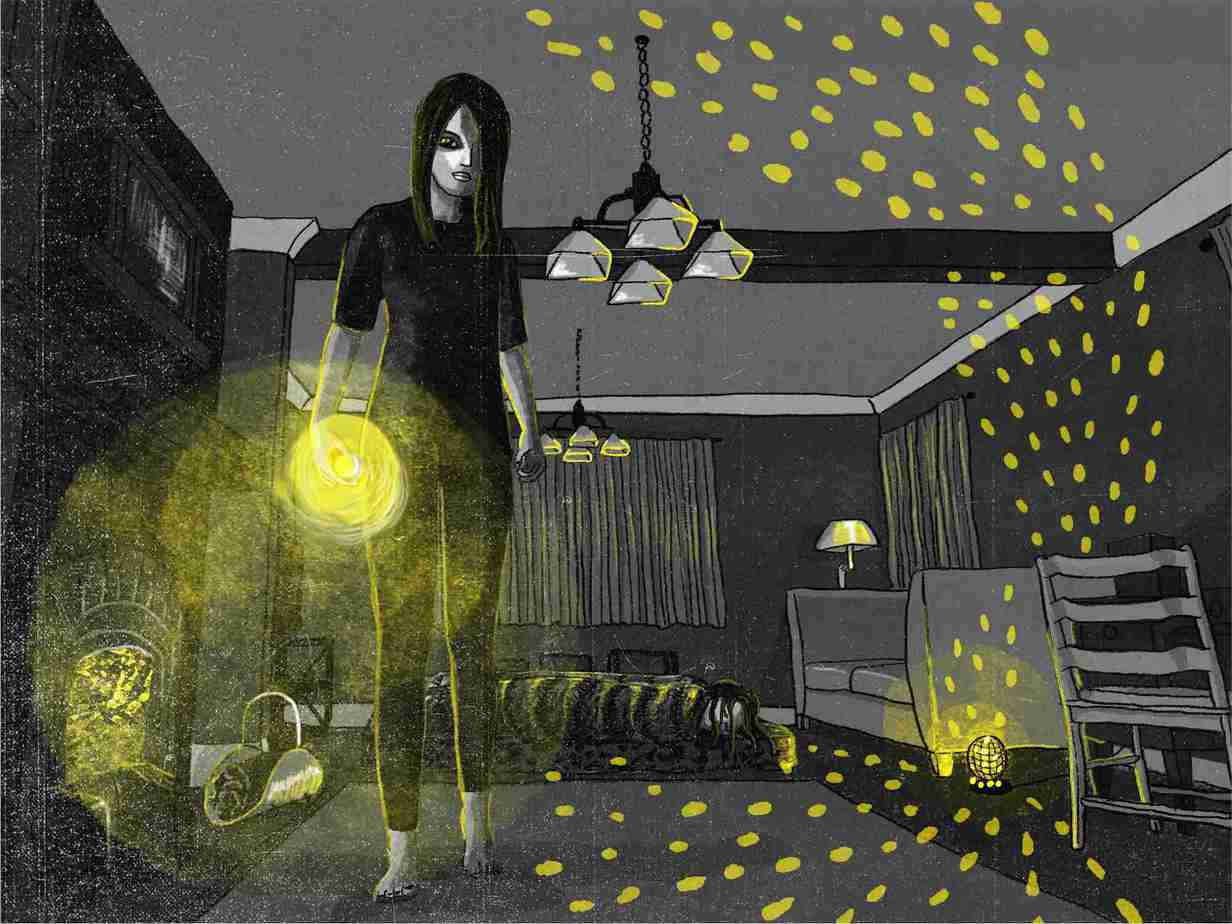

Willow and Scarlett fall asleep before Charlie does. Charlie has started taking coffee, because Neil bought her an iced double espresso on their way home from the birthday shopping and Charlie learned that she likes the buzz. But she hasn’t learned to calibrate the caffeine yet.

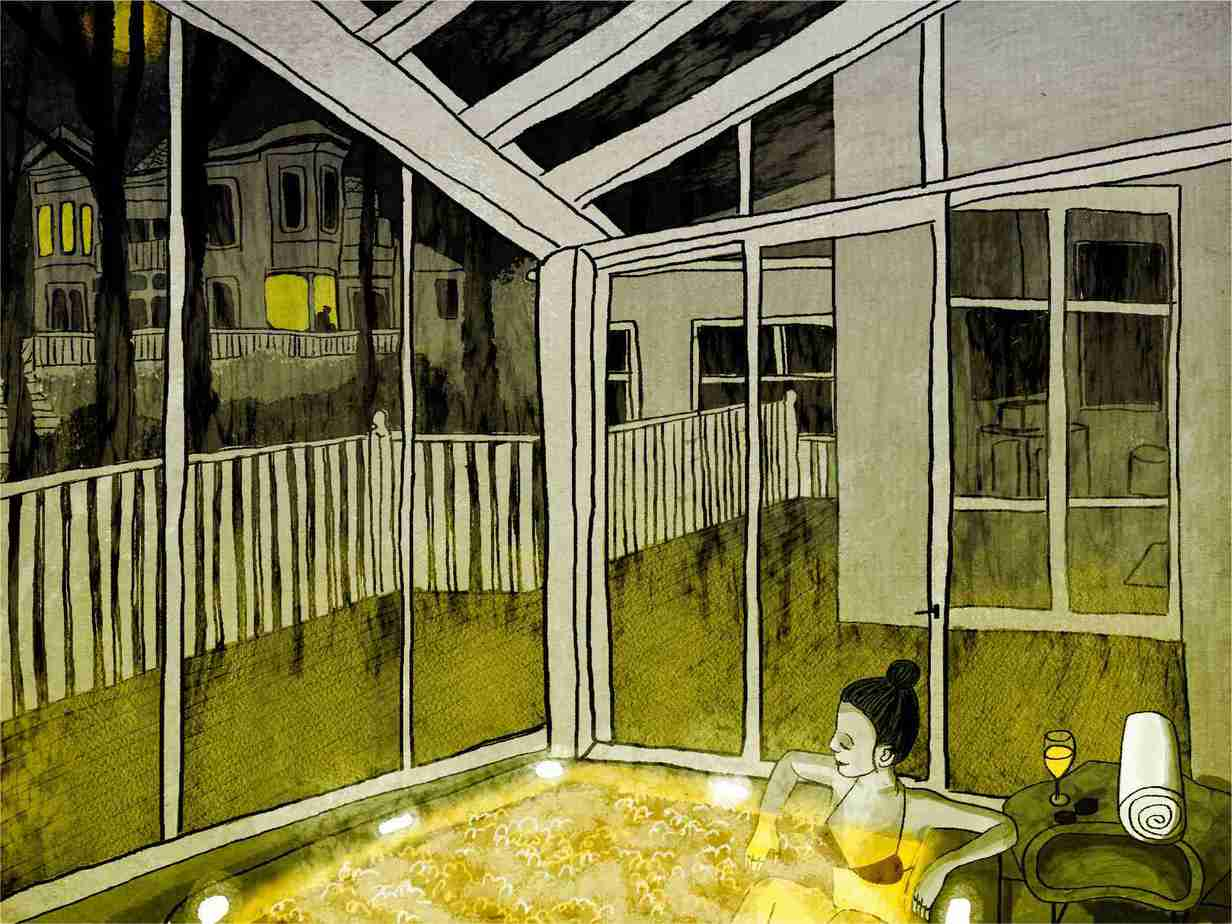

Charlie prefers the night-time over day. It doesn’t matter where she is, at Michelle’s or at Lionel’s, or even at Willow Jensen’s — if she closes her eyes she could be soaking in her Roseneath spa pool or napping in her Roseneath conservatory, stars above her, glitter through glass.

Except she’s irritated by that USB disco ball. It throws ovals of light across the living room. She could swear she hears it hum as it tilts. Then its colours change from pink to green to yellow and all she sees are lemons — a hundred little lemons decorating the Jensens’ walls.

No one has mentioned lemons all evening. But almost every day for the past two months she’s been slotting baby lemons through Willow Jensen’s letterbox. Here’s what Charlie really wanted to know about the inside of Willow’s house. She wanted to know if her lemons through the letterbox had made any impact. Did Charlie think they would be on display in a fruit bowl or something? Because they’re not. Her mum and dad clear the letterbox and plop them straight into the wheelie bin. All this time, Willow hasn’t mentioned any letterbox lemons. She doesn’t mention them, but Charlie wonders what she’s thinking. Willow’s upbeat stupidity knows no bounds, but even she must have worked it out by now, that when the Cheese Boys make lemon jokes they’re really making Willow jokes. Hell, everyone else knows it.

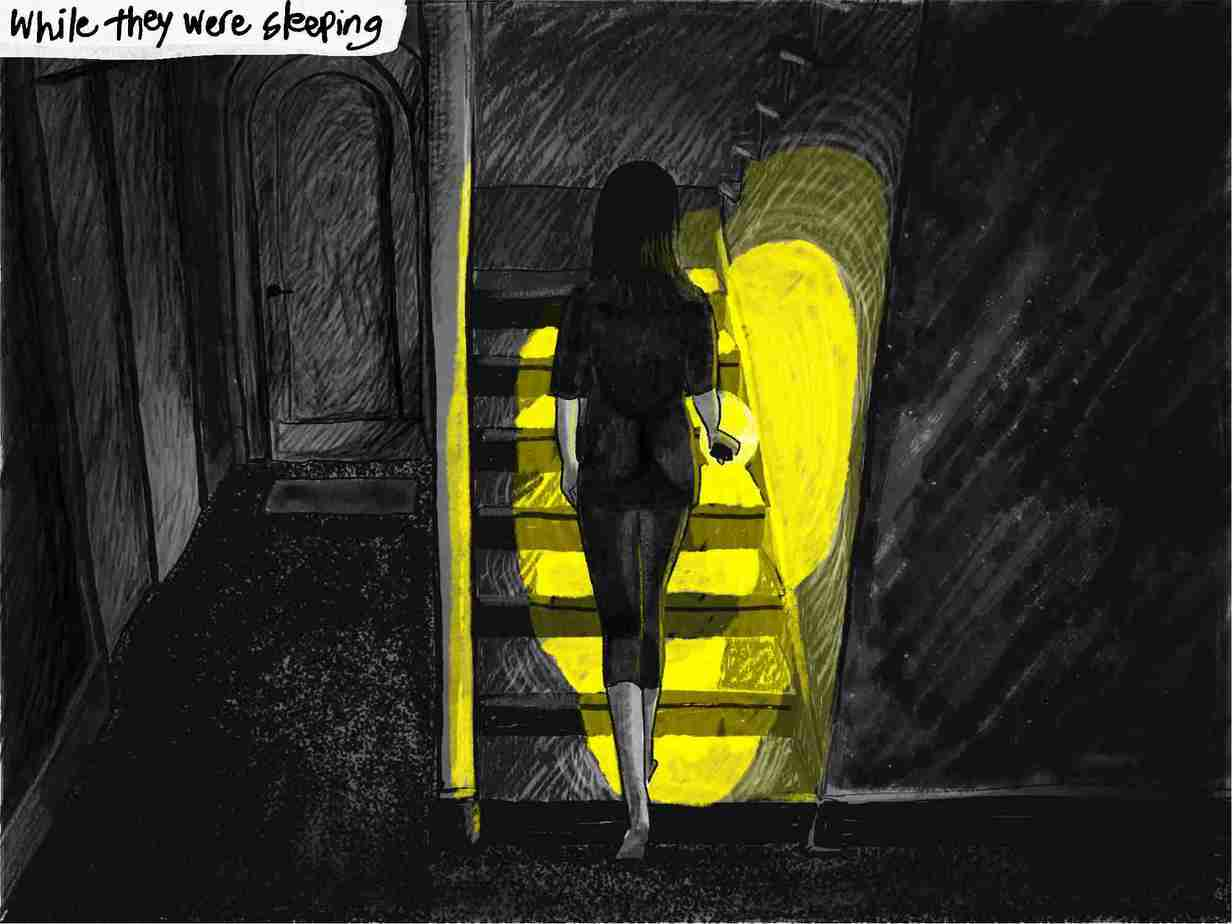

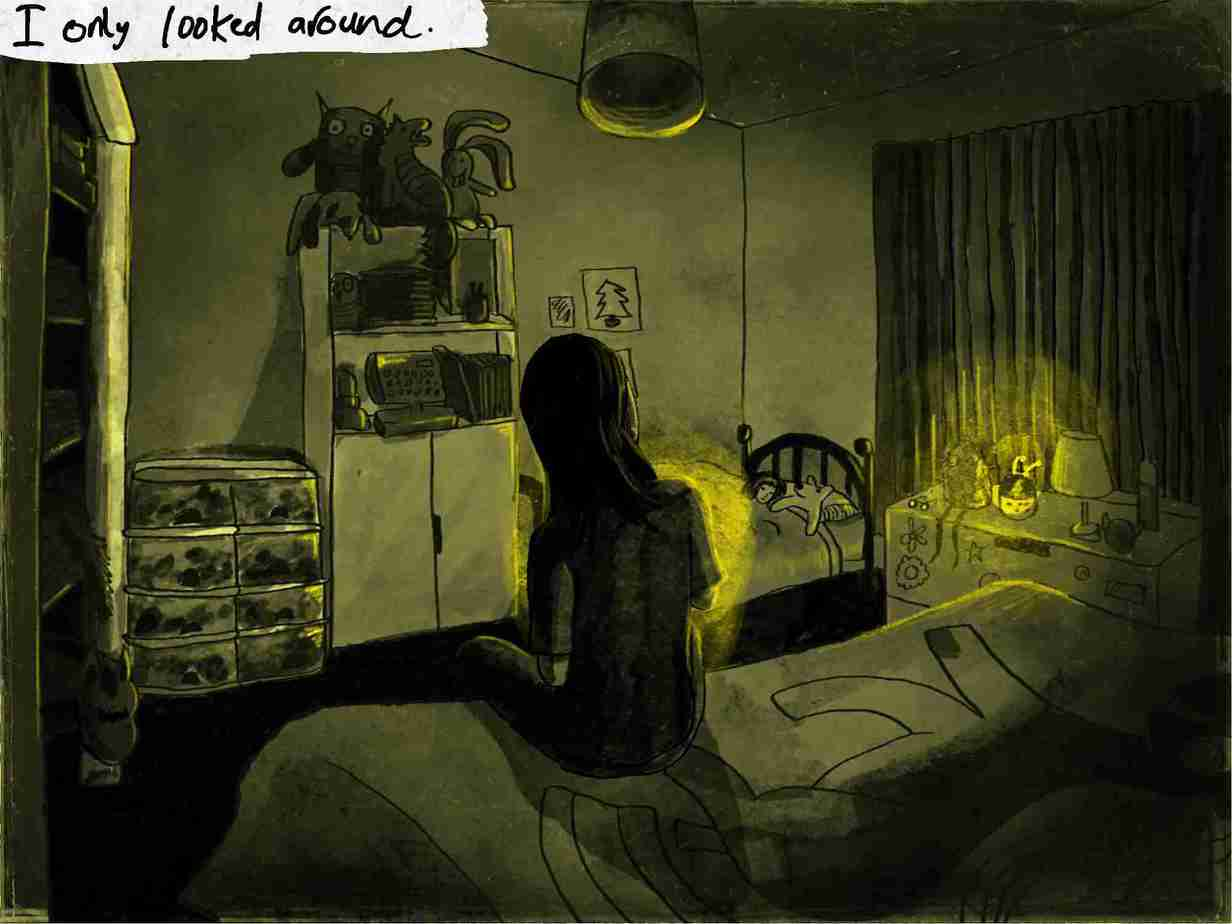

While the rest of the house sleeps, Charlie rises. She explores Willow’s house. She doesn’t expect to find anything of interest. This is just Charlie making an inventory.

Willow’s kitchen is an overflowing cornucopia of pasta curves and honey-stuck lids. Willow’s parents buy budget brands, but lots of them. Charlie tips curry into the aniseed, gravy mix into the chicken stock. She salts the sugar and sugars the salt.

Willow shares a bedroom with her little sister. The sister sleeps on a tiny bed, like something out of The Three Bears. She sleeps while hugging a plush toy. Charlie would like to test if the sister holds onto her precious plushie like a drunk grabs their drink, so she eases it out of the little girl’s arms. It’s like taking candy off a baby, not like that’d be easy. (Babies cry out, don’t they?)

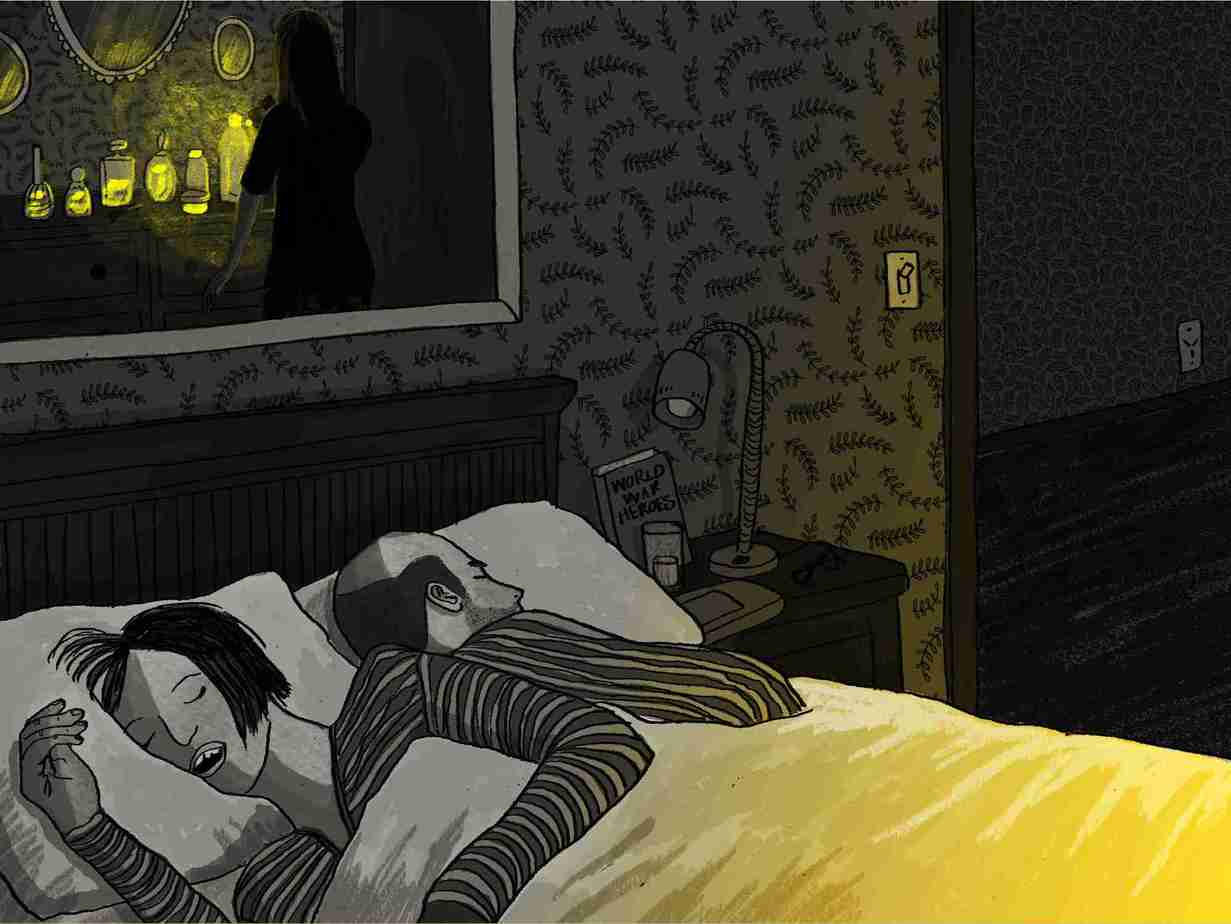

The Jensen family bathroom contains the cleaning supplies. Mr Jensen uses special shampoo for men. It’s not doing him much good, either. Charlie notes the bottle is a third empty, so tops up the cocktail with a long squirt of Janola. She doubts it’ll do much to bleach his hair (that recolouring shit is hard science) but he’ll get an epic eye-sting for sure. Let’s see how he likes them lemons, eh? Let’s see who’s the real ‘Grumpy Groaner’ tomorrow.

Across her bedroom dresser, Mrs Jensen displays a row of pretty bottles. They may be cheap perfumes but she owns a lot of them. The parents breathe rhythmically in their double bed. The father snores a bit. They’re immune to the sounds of fumbling around.

Charlie unscrews the scents and magics up a new concoction.

Poo-wee. She takes a whiff of her handiwork and almost keels over. People can’t smell things in their sleep. That’s why people die of smoke inhalation when their houses catch fire at night.

Mrs Jensen may have smelt like rose-scented baby powder yesterday, but next week she’ll be attending Willow’s meet-the-teacher evening reeking like bruised fruit off the floor of the produce department.

Eventually Charlie returns to her sleeping bag. Eventually the sun rises. Charlie’s dad is making pancakes with faces on them, but Charlie takes off before she’s required to ooh and aah over those.

Charlie’s room at Neil’s is small and she doesn’t have space for extra crap. So a few weeks later she thinks of a use for that 10 pack of gift tags she hasn’t even opened. She will attach the tags to Willow’s lemons.

‘Dear Willow’, Charlie writes, because she wrote ‘To Willow’ on her birthday card and Charlie doesn’t want her to make links. That’s also the reason why Charlie scrawls with her non-dominant hand. When she’s done, it doesn’t look a single bit like she wrote the gift tag tied around this lemon. It does look a bit like Corey Brasher wrote it.

Dear Willow,

Make lemonade with this why don’t you.

Love, Life. x

Masked, Unmasked

It’s windy, it’s wet and it’s cold outside, despite late afternoon sun streaming through the window. Charlie’s in the kitchen at Michelle’s.

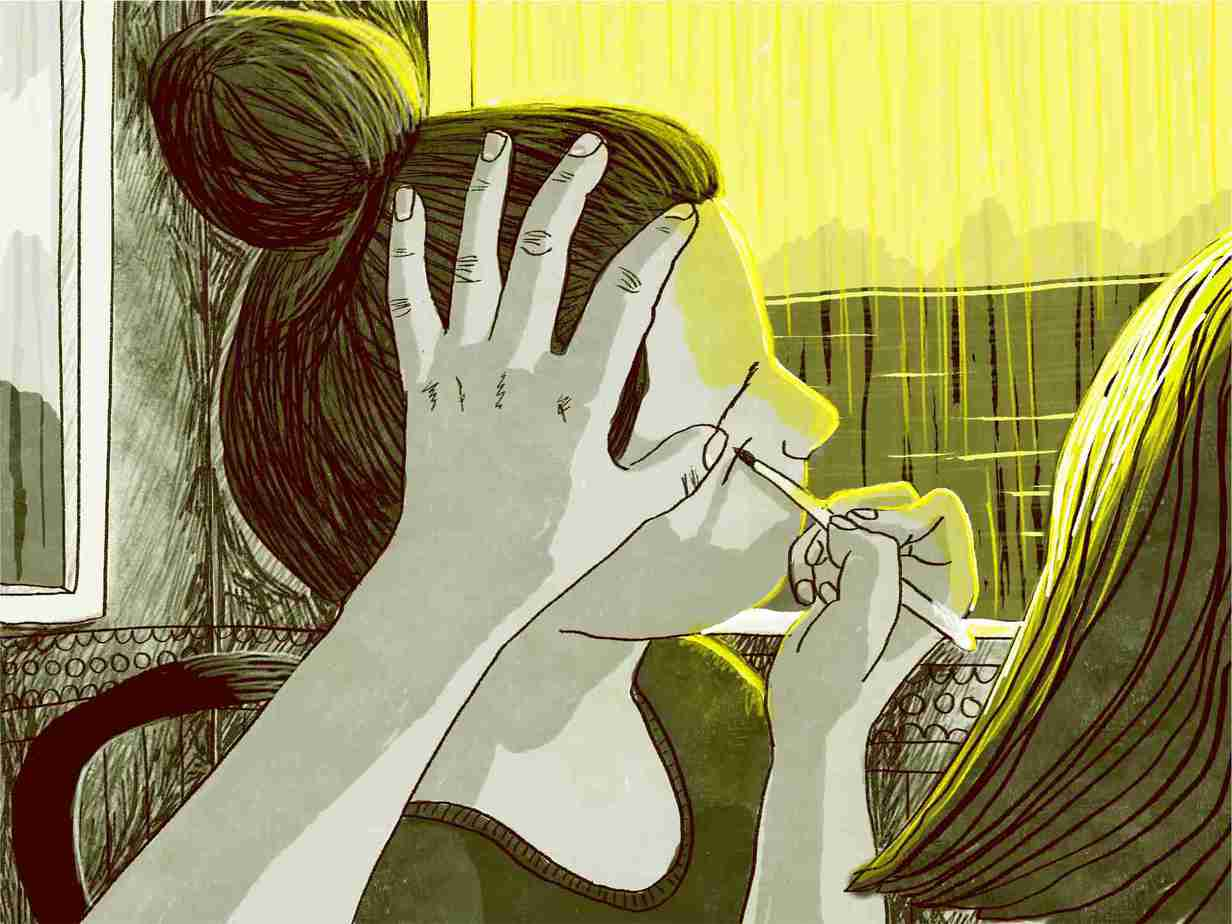

Michelle tells Charlie to make the fishy face. The makeup kit is spread across her dining table. She’s about to contour Charlie’s cheeks.

Charlie is not dressing up for anywhere special. It’s just a boring Sunday in The Hutt but Michelle has decided to do a makeup course as well as finish her hairdressing apprenticeship. This is a lot considering Michelle hasn’t done formal study in about two decades, but she reminds Charlie she’s already good at the makeup.

She is good at makeup, that’s true. Michelle can transform anyone’s face. She used to practise makeup by plastering it on Lionel. Charlie used to think her father suffered through it. Now she knows he probably liked it.

Charlie pretends to suffer through this as Mum’s guinea pig, but she loves to see the result.

“Let’s go plum for the lips.” Mum tells Charlie to smile tightly. “Hey, what are we doing for your birthday this year?”

Charlie can’t exactly answer with her lips like this but she’s over birthdays. Willow’s sleepover was more than enough birthday for the both of them.

“Why not invite a few friends out here for the weekend? A special birthday glow up. I’ll do everyone’s face. Would Scarlett like that? Scarlett’s got beautiful bone structure. I’d love to set to work on her.”

Charlie smacks her lips together. “She wouldn’t be into it.”

“Oh, Charlie. Ask her.”

Charlie has been mates with Scarlett since forever and doesn’t have to ask her. Scarlett would not want Michelle all up in her face. As well as beautiful bone structure, she’s got pretty intense acne. She’s self-conscious about it. She’s never told Charlie this, exactly. That’s Charlie’s wonderful cognitive empathy kicking in, right?

“What about that other little girl? What’s her name? Willow.”

“Can you do kiddie face painting, because that’s what Willow Jensen’d be into. She’d want a pony on each cheek. That girl eats glitter for breakfast.”

Michelle laughs. “Hey, maybe I should upskill in face painting. Kiddie events might be less stress than weddings and school balls. Maybe I’d make more cash, too.”

Then Michelle tells Charlie to look at the ceiling. “Sorry, Charlie. I keep going on about money these days. Look at me.”

“You want me to look at the ceiling, or at you?”

“Look at me. Hear me when I say, you don’t have to worry about money. We’re really very lucky. This is a crappy little house, but it’s our crappy little house. When your father and I split the assets I bought this freehold. My life isn’t over, Charlie. Sometimes it takes a surprise to kick you into action. It’s all about framing. I could feel sorry for myself. Instead, I’m a strong, independent, middle-aged woman and I get to follow my passions professionally. We’re going to be okay, Charlie.”

“I know it.”

“You don’t need to feel embarrassed about living here, pumpkin.”

“I don’t.”

“What, then? Why won’t you invite your friends out?”

“I just haven’t.”

One, Charlie sees enough of everyone at school. Two, Charlie likes a bit of privacy. She doesn’t need to tell everyone every last thing about herself.

More practically, if she invites Scarlett and Willow out here to Michelle’s they might notice the lemon tree growing out back. Lots of people with yards have lemon trees, probably. Maybe even Corey Brasher. And it doesn’t even look like a lemon tree when it doesn’t have lemons left on it, unless you know your trees. But still. Knowing Willow, Willow knows trees and hugs them. It wouldn’t take a genius to realise it’s really been Charlie leaving lemons in the Jensen family letterbox, even though it requires Charlie walking an extra half kilometre to get to her place, and who’d guess that level of dedication.

“I’m not feeling birthday-ish this year.”

“True friends love you for you, not for your big fancy house.”

Charlie needs to divert this conversation. “What about you, though, Mother? Where are all your friends these days? I don’t see them making the forty-minute drive up the highway.”

“What would you know? You’re mostly in the city.”

Michelle reaches for the dramatic lashes and softens her voice. “You’ve got your father’s beautiful big eyes.” She applies glue to the edges and waits til it goes tacky. “Now close your lids like they’re sleepy.” She glues them to Charlie’s lash line.

But Charlie’s already noticed that Michelle’s eyes are watering, not hers. It’s because she mentioned her old friends, the ladies who used to lunch.

“Mission accomplished?” Charlie asks.

“A little extra gel liner, methinks. Those massive eyes of yours let you away with murder, my girl. Always have, always will.”

At last Michelle is done and hands Charlie the mirror.

“Yeah. You nailed it,” Charlie says.

“I doubt I’ll get clients asking for ‘evil’,” Michelle replies, “but this was a useful learning exercise. I definitely got my contouring practice in today.”

After weekends with Michelle, Charlie takes the Hutt Valley Line back in to Wellington. Then she stays at Lionel’s until Friday afternoons.

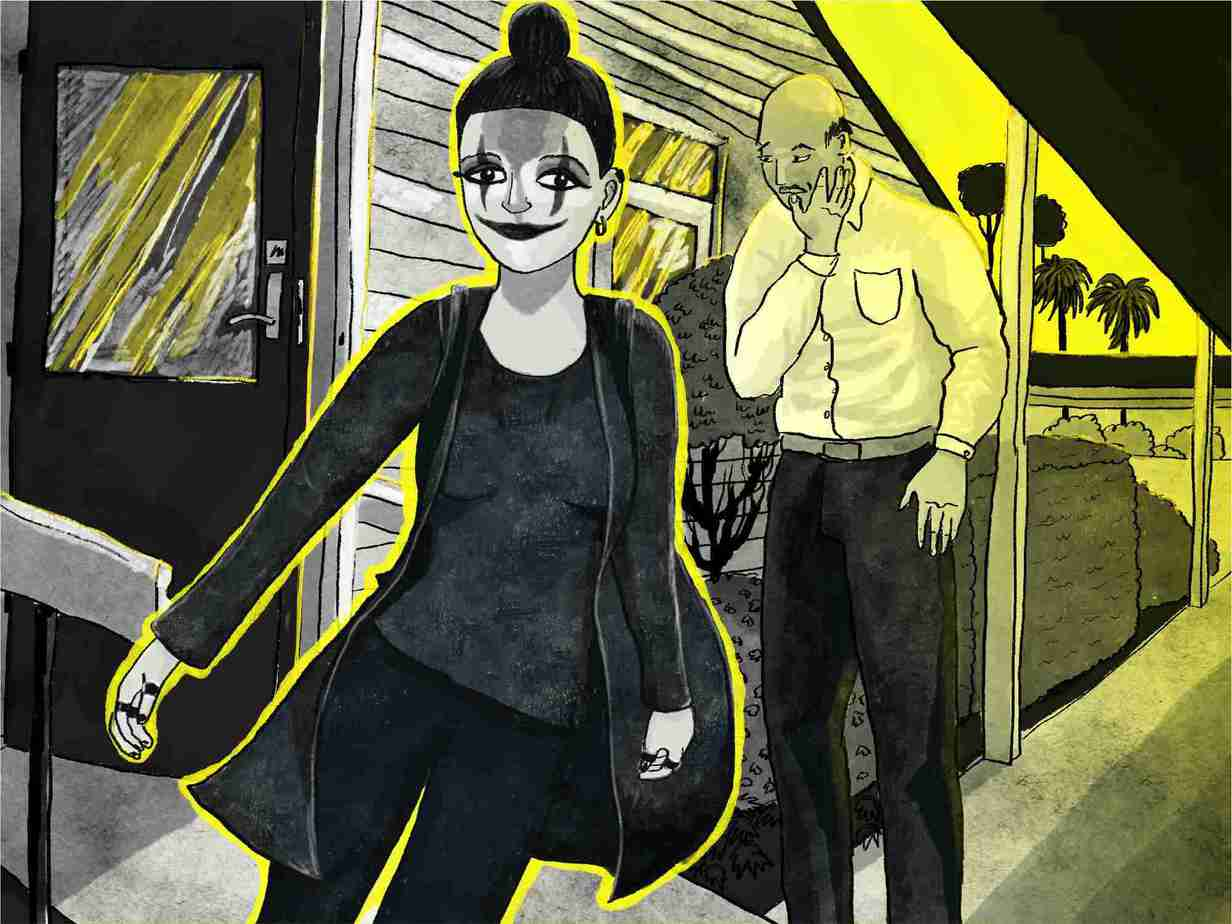

This morning she gets a seat by the window. The sun comes up over the water. An evil face looks back at her in the glass. She hasn’t washed off the makeup.

Michelle told Charlie she should not have slept in it because skin needs to breathe. That only applies to amphibians. Michelle clearly sees the amphibian in her precious daughter.

But before Charlie says goodbye for the school week Michele hugs Charlie tight and admits she’s impressed at how well her makeup job lasted overnight.

At school, Scarlett tells Charlie the look really suits her. Charlie wouldn’t go that far. She needs some more piercings: cheeks, albert, both nostrils, septum, two stretched holes in each lobe. Now that would really suit her.

The Cheese Boys pretend Charlie’s a new girl, every time they see her.

Teachers are impressed, because they think Charlie did the makeup job on herself.

Only the science teacher jumps out of his skin for real. It’s lunchtime, and Mr Rees almost bowls into Charlie emerging from her lunchtime hiding place, in an unlocked classroom. That guy’s highly strung, as Charlie already knows.

“What the—Charlie? What are you up to, Charlotte?”

For one split second Charlie forgets she’s wearing the slap. In that moment Charlie thinks he’s finally figured her out. He knows all the uncharitable thoughts that run through Charlie’s head.

Of course, Mr Rees doesn’t know much about Charlie at all. That’s why he’s always jumpy.

“What’s with the scary face?” He points to his own face, circling his mug with a forefinger. “Are you acting in the theatre thing?”

Charlie offers reassurance. Acting is her life, she’s not going to do it for fun and friendship. Mr Rees is relieved to hear the school production does not involve Charlie, and yes, Charlie will be there for the Genetics and Evolution test, and yes, Charlie is really looking forward to it.

“Very funny.”

Then Charlie tells Mr Rees about the dab of whipped cream near his dimple.

“What?”

“Want me to wipe it off for you, sir?”

He gets flustered, and uses his cuff to try and wipe it off himself.

“Other side,” Charlie tells him.

“Is it gone?” He’s turning bright red. That is one physiological reaction Charlie will never get her head around.

“Your face has been decorated since morning assembly,” Charlie tells him. But that’s completely ruined the effect, because now she remembers he had his cream bun after morning assembly, and he knows that too. Charlie saw him tucking into it at interval outside the canteen. He was meant to be on yard duty but he was staring dolefully into his coffee cup. There was never any cream on his face.

Even with the lemons in her pocket, Charlie gets dangerously bored and wants to dig her nails into something. Something with skin.

This evil makeup does suit her better than her real face. If it wasn’t so much hassle she might learn how to do it herself. She’d wear it every day. If only she could tattoo it on.

Willow says nothing about Charlie’s evil maquillage because Willow is away. Absence is unusual for her. She normally comes to school snorting and sniffing into her elbow because she doesn’t want to miss out on curriculum.

“Willow’s in Hamilton,” Scarlett tells Charlie. “Her great grandmother died.”

“Finally.”

Charlie doesn’t say that bit out loud, by the way. She catches herself just in time.

She decides not to deposit lemons in Willow’s letterbox until the Jensen family are back. Chances are, a neighbour’s collecting their mail, and those lemons aren’t meant for any neighbour. She keeps the weekly store of letterbox-lemons in her pocket. She digs her fingernails into them during the school day. It feels good. The lemons off Michelle’s tree are getting bigger and riper now, but Charlie has kept a store of smaller ones. Her hands smell a little bit lemony.

Fresh lemon smells better than Voodoo body spray, the rank stank that assaults everyone all day at school. Cheese Boys share the same can of factory-fake spices. Bergamot, lime and mandarin. They think that combo transforms them into dark and mysterious men. Oh, if only they knew.

It’s the following Wednesday. The Jensens are back from the funeral. Charlie knows this from glancing through their front window on her detour to school. She sees shadowy movements inside. She’ll keep the daily lemon drop for her afternoon walk, when their house is always empty.

Charlie doesn’t want Willow to catch up with her either, so she strides it out. She’s already halfway to school by the time Willow rushes up behind.

“Charlieeee! Long time no see!”

Charlie asks how her holiday went, because that’s what you do.

“Oh, it wasn’t a holiday. Sadly, my great grandmother died.” She assumes Charlie doesn’t know.

“Shit. Sorry. Was it a big turn out?” That’s what people say, isn’t it?

“Well, I’m looking on the bright side. She had a good run. She was ninety-eight! Really, if you think about it, we were lucky to have her as long as we did. Very, very lucky.”

This is the conclusion Charlie had already drawn. Honestly, if Charlie’s a psychopath, what’s the downside? She gets to skip the hard parts and arrow straight to the logic of the matter.

“I wrote her a newsy letter last Christmas,” Willow continues. “My uncle read it out for her. She didn’t know who it was from, but she said it was very lovely.”

Charlie is actually starting to think Willow and herself are flip sides of the same coin. If the kid bounces back this quick, maybe she’s been faking it, like Charlie always does.

“What about you, Charlie? Do you still have your greats and your grands?”

“Nope.”

Charlie’s not about to get into it with the likes of Willow Jensen, but she does technically have grandparents. They live in the South Island and they don’t speak to her parents, so they don’t speak to Charlie either. Lionel’s parents kicked him out of home at the age of fifteen after finding him with another boy. Michelle’s parents never approved of their match because everyone knew about Neil and the boy. And it’s not like their recent separation magically fixed all that old history.

On the topic of family history, Charlie’s been wondering if Lionel’s her genetic father. No one’s said he’s not, and from certain angles they look enough alike. But Charlie wonders about the darkness inside herself. It must be an inheritance from someone. Her bubbly hairdresser of a mother is alien to Charlie. As for her designated father figure, Lionel harbours his own darkness, but only the sardonic, regular kind that comes after decades of days in which life lets you down slightly, because you were born expecting utopia. Charlie was never let down. She was born this way, alert to the dirt and the grime, seeing it everywhere. She doubts two basically nice people could make a child like her.

“I got to see my cousins,” Willow is saying, because asking about Charlie’s extended family is only an excuse to keep going on about hers. Then she starts listing their names and ages. In Charlie’s ear, straight out the other. “Oh, look, Charlie!” She pulls off her mitten and thrusts her little pink hand in front of Charlie’s face. “I used the French manicure set you gave me for my birthday. My older cousin Lucy/Becca/Olivia put it on for me. We had such a fantastic time together… blah blah blah.”

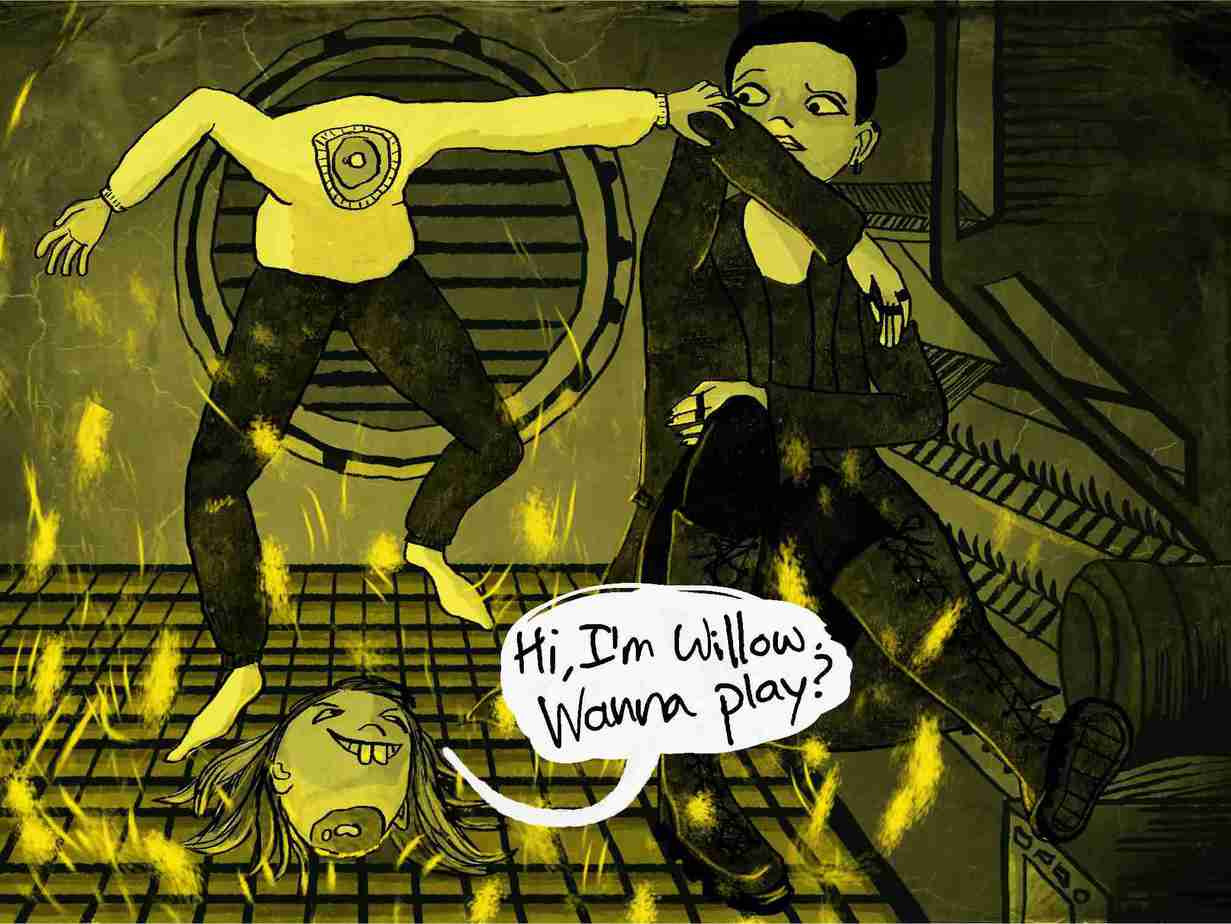

God. Charlie feels like she’s walking to school alongside the monster in a horror movie. Just when you think the hero has killed it dead, the abomination comes right back to life. Its head may be on the other side of the abandoned factory or its legs may be severed clean off. But one slimy, grimy hand comes straight for your jugular, or maybe your earhole…. Yap, yap, yap.

Willow Jensen is basically a monster. The optimistic, manicured flip side, for sure. But a monster just like Charlie. Perhaps Charlie just wanted to see the monster come out. She wants the full measure of it. Surely the kid can’t be for real. Surely Charlie is not the problem, here.

Everyone’s the star of their own damn freak show.

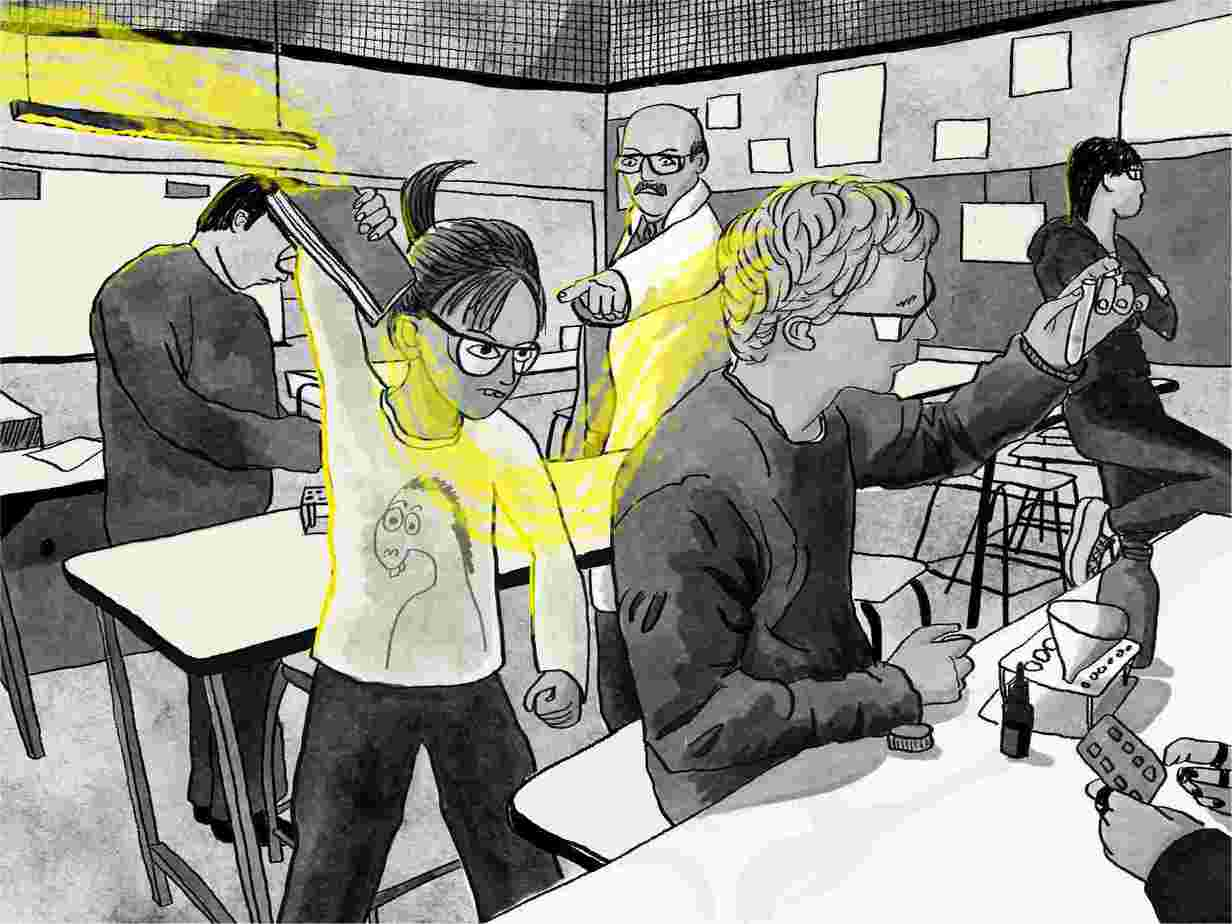

Speaking of freak shows, not long after, Willow Jensen cracks the shits in science.

She thought the big assignment was due in another week, but she had the date wrong. She relies on a paper calendar, so doesn’t get alerts.

Mr Rees forgets Willow’s been at a family funeral and says, “Disappointing, Willow. That’s not like you.”

No teacher has ever expressed disappointment in Willow. Willow can’t cope with that.

So when Cheese Boy Corey Brasher mutters something about lemons, Willow picks up her science book and in a ridiculous manoeuvre hardly befitting a warrior princess, thwaps it across the back of his head.

The assault can’t have hurt. But there’s a zero-tolerance policy regarding violence, and Mr Rees doesn’t get the nuance of any situation ever, so Willow gets all the steps. In the end she apologises to Cheese Boy Corey.

That’s what kicks the most. Charlie wouldn’t have apologised if it was her in Willow’s situation. Charlie’s glad she whopped him one. Science lessons are otherwise boring as hell.

Charlie’s 14th Birthday

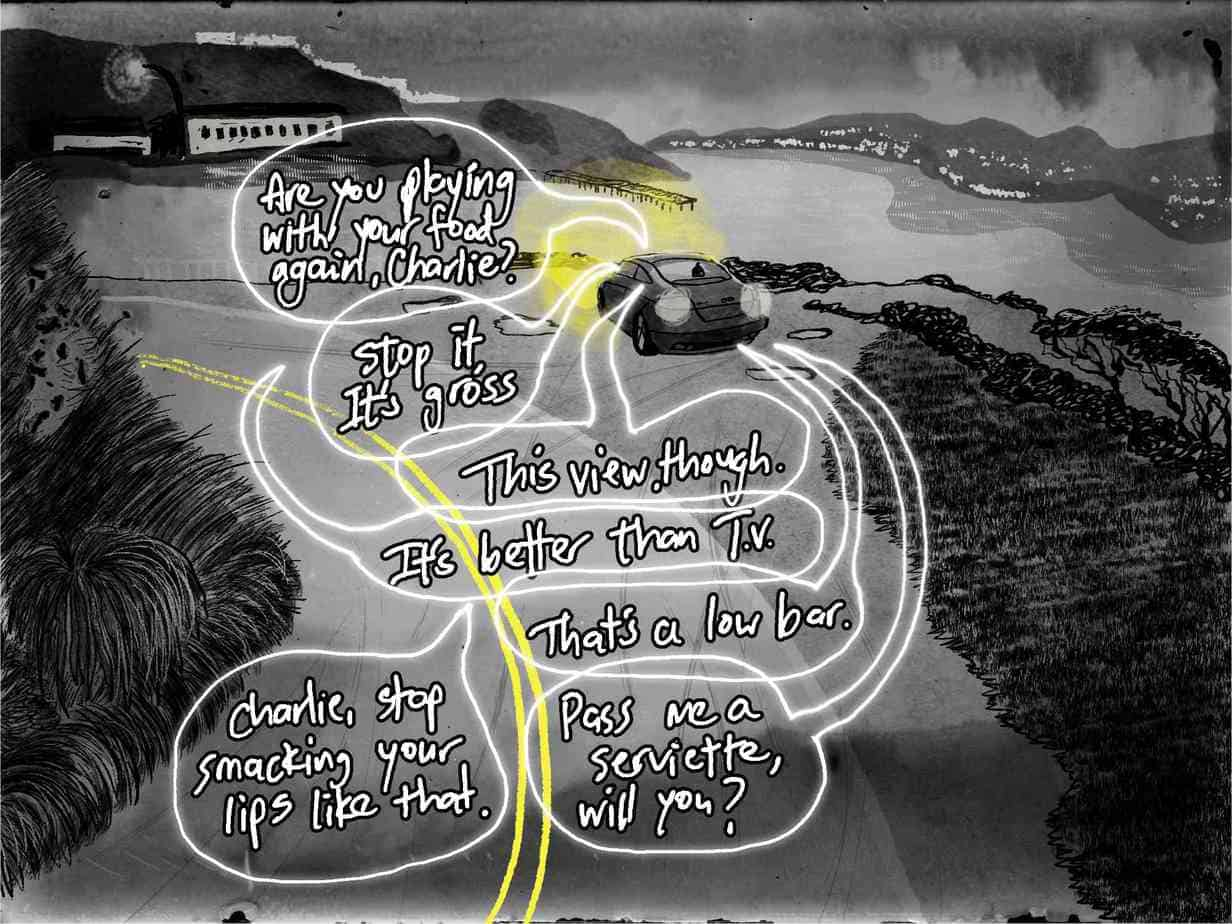

Charlie’s actual birthday is on a Tuesday. She’s at Lionel’s. Neil is also at Lionel’s. It was Charlie who invited him. Lionel offered to cook Charlie anything she wanted, but Charlie doesn’t like whatever he cooks. If Charlie invites Neil, he’ll be the deciding vote for her favourite, which is KFC. Charlie likes the idea of secret herbs and spices. Lionel agrees to this, but only if they don’t have to sit inside a fast food restaurant, which he finds depressing on a Tuesday night. Charlie asks Lionel to drive the three of them to Shelly Bay. It’s windy and cold there with spits on the breeze, but it’s Charlie’s birthday so she gets to choose. This is her favourite kind of weather. But Lionel doesn’t want to get out of the car, so they sit inside, eating chicken and chips. Charlie likes to peel off the chicken skin and examine the veins on its underside. Now and again she looks up from her feed to admire the view.

There’s literally nothing right here but a pot-holed patch to park on. But it’s a great spot, because from the back of Lionel’s car, to their right, there’s a view across the water to Charlie’s favourite hill. She’s pretty sure she knows which little white dot is her house, too.

Charlie asks if Lionel can see it, too. He says Charlie must be imagining things. The Roseneath roof is nestled behind tall silver oaks.

Sometimes he acts like they never lived in Roseneath, with the spa pool, the billiards table, the rumpus room.

Neil changes the subject. He advises Charlie to enjoy the advantage of youthful eyesight while she has it. Lionel turns the car engine back on to keep them all warm. Neil asks if Charlie wants to do anything else for her birthday. “Skating, perhaps? Hey let’s finish strong with a drive-thru soft serve. Something, anything? Anything, so long as it’s indoors?”

Yeah, nah. Charlie has zero depth perception today, and has already kneecapped herself twice on Lionel’s coffee table. Also, she’s too full of chicken for a soft serve.

“Ooh! You love scary movies! Perhaps your old man here will let us catch a late one, even on a school night?”

“I can watch a movie at home on my own.”

Neil stuffs the KFC rubbish into a bigger bag for disposal. Then he says, “Cheer up, Charlie. You’ll find your people eventually.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I hated high school and high school hated me. But look how cute and popular I am now!” He tilts his head and grins at Lionel with all of his teeth, then leans in for a smooch.

“Pucker up, schweet-heart.”

Lionel says, “For pity’s sake get off me Neil, I’m wearing a full beard of grease.”

“I’ve got people,” Charlie says from the back seat.

“Sure. Yeah, I know.” Neil’s trying to sound light-hearted.

Charlie has Scarlett, for instance. Neil wouldn’t know this but Charlie’s had Scarlett her entire life. Until her parents split up they lived next door. They went to the same kindy. Teachers in primary school would mix them up. That’s how similar they seem. Charlotte and Scarlett. Even the names, see.

Scarlett has lots of other friends now, but Charlie only needs one person. Scarlett has higher social needs than Charlie. Charlie is low maintenance.

She considers this an advantage because people are ultimately annoying, even if you call them your friends. Lionel has this old song, which Charlie won’t let him play when she’s around but the lyrics go, “People who need people are the luckiest people in the world.” This is such rank bullshit. Mo friends, mo problems.

On the drive back to Lionel’s, no one says much at all. It’s Charlie’s birthday, and Charlie gets to be right. She’s right about her own friendship situation.

And because it’s still Charlie’s birthday, she asks Neil to drive past the Roseneath house.

“To shut you up,” he mutters.

If they’re driving past the Roseneath house they are also driving past Scarlett’s house, whose perfectly intact family will always live in Roseneath. If Scarlett’s not wiping the dishes or reading the assigned novel she’ll be texting someone right now, discussing their homework or talking them down from some emotional crisis. If Charlie had asked Scarlett out for her birthday she would definitely have come. It’s not like she feels sorry for Charlie, like she clearly feels sorry for Willow Jensen. Charlie knows Willow irritates Scarlett as much as she irritates Charlie. She must do. Unlike the Cheese Boys, Scarlett’s too Nice™️ to say it out loud. Charlie doesn’t need company on her birthday. But she does need to know that the world would bend as she wishes, if she were to choose company.

What’s so great about ‘nice’? Why won’t anyone admit that nice people are only nice because they want you to do what they want? Niceness is an evolutionary adaptation. See, Charlie was paying attention for that particular five minutes in science class with King Cheese, Mr Rees.

By the time they get back to Lionel’s it’s fully dark. Neil hooks up Charlie’s old game console for a sing off. Charlie’s going along with it and everything is fine.

Then it’s ten thirty. Charlie, Lionel and Neil are starting with the yawn pong, so Neil says he’d better make tracks, back to his drafty old share house, back to a dirty kitchen, back to his drunk-snoring flatmate.

He looks at Lionel when he says it, like there’s a question in there.

Lionel just sort of shrugs. Charlie notices her father’s eyes flickering to her. Owing to her excellent cognitive empathy she understands the subtext of that conversation before he’s three words in.

But Charlie doesn’t need Neil staying at Lionel’s while she’s here. Maybe in future Neil hanging about may come in handy for Charlie, but right now she’s enjoying the power of saying no, which is actually saying nothing at all.

“Fine.” Neil sighs theatrically. He says he’ll only leave after Lionel and Charlie sing an upbeat duet, “because we can’t let Charlie end her one and only fourteenth birthday on a low note, can we?” and Charlie gets exactly how annoying Neil must have been in high school. Nice people give her the shits.

Way Back In May

The Roseneath house sells quickly. On the market in April, sold in May. Charlie overhears her parents arguing about maybe not asking enough for it. Honestly, it’s the only arguing she’s heard so far. For all their deeper issues, Lionel and Michelle were never the shouty type.

It’s the day of the handover.

The real estate agent doesn’t care what Charlie overhears. Charlie’s parents may keep stuff from her knowledge, but other random adults are constantly saying stuff in front of her, like she’s some ignoramus little kid. Charlie has noted a common cognitive bias: no matter how close she’s standing, people will think she’s not listening if her back is turned. It’s a lizard brain thing.

Imagine Charlie standing in the Roseneath kitchen, gazing out the window towards Scarlett’s house.

“Thanks heartily for making such a wonderful job of cleaning,” the real estate woman says to Michelle.

Charlie’s mother doesn’t tell the woman they got professionals in. “Oh, no problem,” Michelle says brightly, like she descaled the showers her own self. Like she hasn’t been crying her eyes out all morning….all month.

“The gentleman moving in, do you know what sold this lovely property for you? It wasn’t the fixtures, it wasn’t even the view. It was the low maintenance garden,” says the real estate agent, triumphant. “Mr Tan divides his time between Wellington and Hong Kong, you see. He had his eye on another property round the corner but that was really a gardener’s garden.”

Divides his time, you say?

Charlie’s ears prick up. But she keeps her back to them both. She’s already wrested the front door key off her key ring and slapped it on the bench as required. Her parents have forgotten she also has duplicates to the side doors. She’s just now, right this instant, decided she’ll be keeping those.

“…and I’ll thank you on behalf of Mr Tan for leaving all the house documents in tip-top order,” continues the real estate agent. She refers to the stack of light reading Michelle has placed on the granite breakfast bar, next to that row of keys. Instruction booklets mainly: the dishwasher, spa pool, internal vacuum system, security alarm.

“No problem at all,” Michelle says weakly. Then more bitterly, “I hope Mr Tan enjoys his dream house.”

Finally the real estate agent is obliged to acknowledge the emo chick by the window. “Have you said your goodbyes then, dollface?”

“Dollface wouldn’t say no to a moment of sombre meditation.”

“Of course. Of course you need a moment,” says the ‘dollface’ woman, who doesn’t know if Charlie’s being sarcastic or if she really is an Emily Dickinson tryhard. Charlie earns a side eye from Michelle, but achieves her moment of reflective solitude. The grownups make smalltalk out front.

It takes all of two seconds to nab the instructions for the security alarm and button it inside her coat. She’ll leave that scrap of paper with the alarm pin written on it. 2132. It’s a perfectly good security code.

It’s not really ‘stealing’ to take an instruction booklet, in case anyone’s conscience is pricked. One can find anything online these days, including instructions for every alarm system under the sun. But with any luck, our elusive Mr Tan will be far too busy with his overseas financial projects to school himself up on how to reset the tricky thing.

Charlie’s Birthday Week

By August, Charlie has a good thing going.

As far as she’s concerned, a birthday celebration lasts an entire week. During that week, you sleep as late as you want, do zero homework, eat dessert for dinner, imbibe as much iced coffee as you can handle and generally answer to no one.

By Friday she has watched about eleven movies into the small hours at Neil’s. Normally on Friday night she’s already taken the train to Michelle’s, except Michelle has something on this evening. Charlie thinks it’s a date. She hasn’t pressed for details. Doesn’t even want them. Long story short, the adults have decided that Charlie will join Lionel and Neil for their Friday night whatever.

Since Charlie expressed no desire to do anything, the guys have decided on a movie night in. Lionel thinks Neil must see Silence of the Lambs.

“You two watch your sheep documentary and I’ll enjoy YouTube in my room,” Charlie says. “I won’t bother youse if youse don’t bother me.”

“Oh, it’s not actually meant to be a sheep doc—“

“She’s trying to crack a joke,” interrupts Lionel. “Charlie’s got the entire script memorised. Hey kiddo, if you’d prefer to blob in front of a Shortland Street highlights reel alone in your room, that’s cool. I’m not judging.”

“First I’ll cook up some fava beans and pour you both a nice Chianti. How’s that grab you?”

Charlie doesn’t know what fava beans are. She does go to the kitchen but she pops a wok full of corn. She smothers the popped bits in butter and icing sugar, divvies the lot into two bowls and makes out like she’s going to be hanging out in the bedroom all evening.

“Enjoy the experience, Neil, you pop-cultural pauper.” Charlie takes popcorn to the bedroom and clicks shut the door.

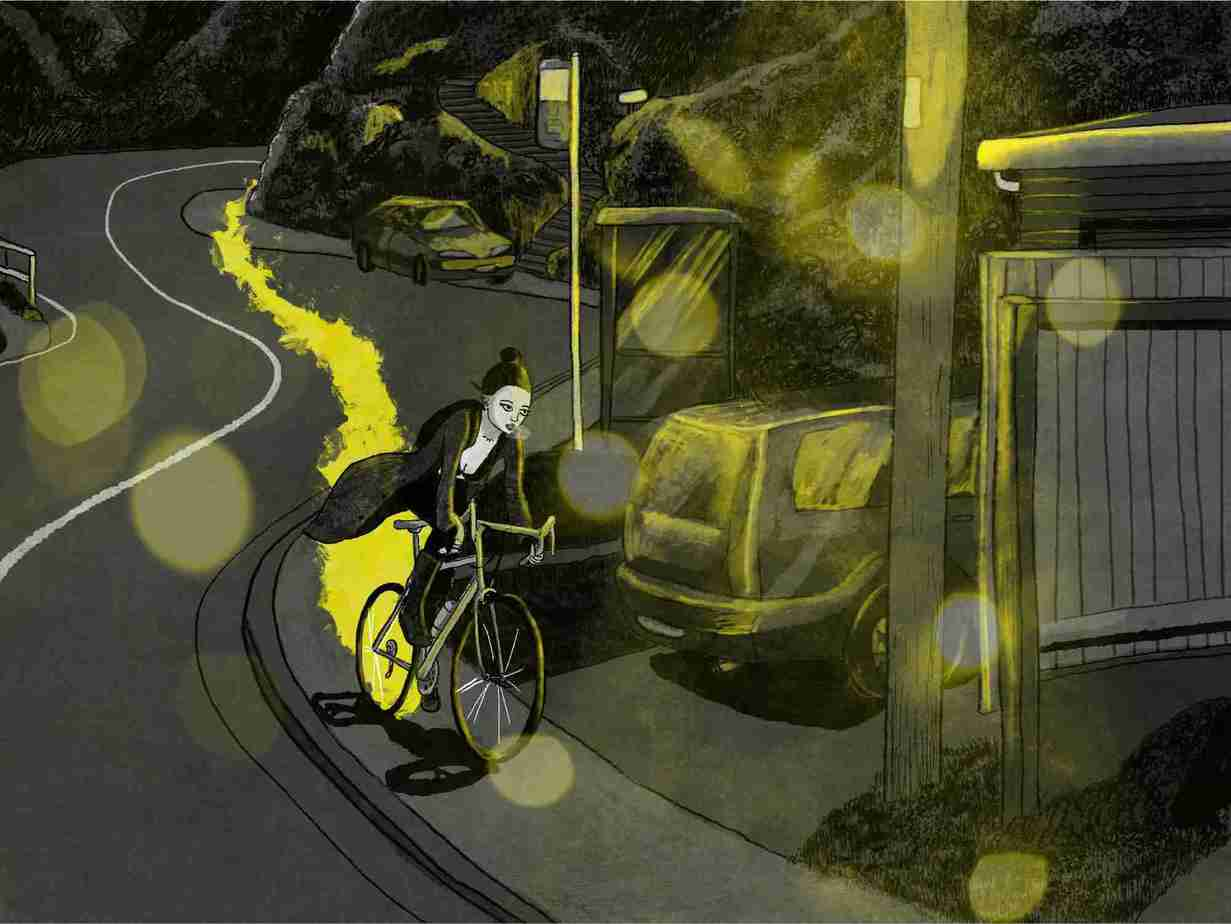

Charlie doesn’t like popcorn. She despises how wayward husks get stuck in your soft palate. She sets up her laptop to stream noisy content through tinny speakers, changes her outfit, then exits via the bedroom window.

Charlie returns to her real house, which is 40 minutes walk away in Roseneath.

The trip’s much quicker on Lionel’s pushbike. The bike doesn’t have lights on it, and she’s meant to be wearing a helmet, but she zooms through the dark along empty footpaths. In her black clothing, Charlie is invincible and invisible.

This degree of invisibility requires the alertness of a panther. Cars can’t see her, so she scans every driveway, every laneway. At any given moment she could knock a pedestrian flat, because she can’t see who’s coming round the bends until she’s already upon them. She can’t hear footsteps at this speed.

The cold and the dark exhilarate.

She’s at Roseneath in no time at all.

Charlie has been keeping tabs on the guy who moved into her house. His last name is common and unsearchable, but according to the documents she scanned on the bench, the guy’s first name is Tiburtius. Mr Tiburtius Tan. The only Tiburtius Tan on the dating apps, would you believe it? Ha hahhh. The pool of Wellington singletons is small. You find the same crew on all the main platforms. Burt’s on Tinder and Bumble. Charlie did her research and summed him up before opening their conversation. She scrolled through his Twitter feed. It was very boring. He’s one of these guys who loves to boast about swanning around airport business lounges. He posts a lot about finance stuff. Graphs, mostly, and political hot takes about governments in countries hours and hours from New Zealand.

Early into their relationship Charlie sent him pictures. Oh, not of herself. She considered that, but was all layered up for the cold and couldn’t be bothered taking off her clothes and putting them all back on. What’s the Internet good for, if not for premade nudie pics?

That’s how Charlie and… god, she can’t think of his name without laughing… that’s how Charlie and Tiburtius hooked up. Only online. Charlie has no intention of meeting the guy in person, and she did tell him that upfront. He’s fine with it. Theirs is a mutually symbiotic cyber relationship built on lust: Burt’s lust for skin pics and Charlie’s lust for relaxing long spas at her Roseneath house.

These days Charlie’s got Burt trained to tell her in advance when he’ll be swanning off overseas on finance biz. Charlie encourages him to have fun over there. (She’s not what you’d call a clingy girlfriend.)

Mr Tiburtius Tan hasn’t changed the alarm code, which is surprising for a tech savvy guy with high-end AV equipment. Charlie simply hides the push bike in bushes, unlocks the side door, turns off the alarm and removes the cover from the pool. Chlorinated steam fills the air. She shrugs off her coat and relaxes into hot water.

She doesn’t do anything else, much. Okay, so she’s been through his drawers and cupboards already. For research purposes mainly, though she does sometimes borrow some Berocca, the odd Panadol, a few sheets of loo paper.

It’s weird how people always know where to put their cutlery. Burt’s put his silverware in the same top drawer of the kitchen. He likes his condiments and has an entire fridge door full of them, but he’s never around to make use of his spicy BBQ sauce or his gourmet curry mixes. Charlie doesn’t like the guy’s taste in soft furnishings but he dresses okay. The suits in the wardrobe are tailored and lined. He wears size eight loafers. This guy does nothing interesting whatsoever. Nothing that leaves evidence, anyhow.

Burt’s towels are fluffy, and clearly bought new to match the downstairs bathroom, but Charlie brings a towel from Lionel’s. New towels aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. Towels need at least ten washes before the shiny, water-repellent newness wears off. Until then, they leave bits of fluff all over your damp skin.

Otherwise Charlie might just use Burt’s towel, roll it back up and hope it dries in the cupboard. Not that Charlie needs to justify any dam thing. Especially not during Birthday Week. Not at her own dam house, dammit.

Burt has a godly sound system. Charlie’s downloaded an app and now she can stream music at Burt’s as loud as she wants. Well, almost as loud as she wants. She still has neighbours, ie. The Carters. She likes classical music — the fast-paced, nerve-jangling kind. Mozart’s Symphony #25, Shostakovich’s Symphony # 10, that kind of thing.

She turns it right up. But not so loud the Carters might hear it.

Through the double glazed windows and over the gully Charlie can delineate Scarlett’s head. Scarlett sits at the computer in the Carters’ home office, panicking about maths problems, even though it’s a Friday. Charlie will cadge the answers off Scarlett on Monday, or face the consequences of not handing it in. Whichever proves less hassle.

Why does Charlie return to her former house? Charlie couldn’t say. If the psychologist knew what her young client was up to she might tell it like this: Charlie craves excitement. It’s not the spa pool that draws her back to Roseneath. It’s not the nostalgia. It’s not even her parents’ breakup. The girl demonstrates surprising resilience on that score.

Charlie is driven by different cogs. She loves that she might get caught, if not by Mr Tan himself, then by a neighbour, or by a stranger whose presence she can’t have predicted. That’s why Charlie turns up that music as loud as she does. Glass walls heighten the risk, and risk heightens pleasure.

September

Charlie has used all ten gift tags. Ten lemons, each addressed to Willow, left inside the Jensen family letterbox. And still, Willow won’t mention lemons. Not to Charlie.

So one lunchtime Charlie decides to mention lemons herself. The three of them —Scarlett, Willow and Charlie — are sitting together in a sheltered nook near the gym, catching the first chill rays of spring.

The Cheese Boys amble past, hands in pockets, dropping and kicking a tennis ball between them. They have no smart alec quips for the girls. Since the third term holidays they seem to have run out of food references. They seem low key. They’re waiting for something else to happen, something to inspire a new running gag.

“Sounds like the Cheese Boys are fresh out of lemon jokes.” Charlie says it so the Cheese Boys can overhear, but they don’t reward her with a reply. A tiny fraction of the population provides lasting entertainment, and the Cheese Boys are one hit wonders.

“Meh. They’re not even funny.” Scarlett looks at Willow, who stares at the ground. “Also, they’ve been instructed not to talk to us, especially to Willow.”

Scarlett seems like she knows something.

Then Scarlett drapes her arm protectively around Willow’s shoulders and says to her, “It’s okay. We should tell Charlie.”

Willow nods.

“Someone’s been stalking poor Willow,” Scarlett explains.

Well, this is a bit over the top. “Stalking?”Charlie is incredulous.

“Someone’s been going to her house, like, every single day, leaving notes in her letterbox.”

“What kind of notes?”

“Oh, it sounds ridiculous, which is the entire problem because it’s hard to take seriously. But it’s creepy for Willow. The notes are on tags, tied to lemons.”

“Huh?” Charlie doesn’t even have to pretend to sound confused. Hearing her own actions explained back to her, in words, she does understand how weird this is. Charlie doesn’t understand her own motivations. It’s like another version of herself put lemons in the letterbox. She mostly feels like she’s watching her own life as a documentary. She used to think everyone experienced the world through a screen, but lately she knows that’s not true. When Normals feel sad, they really feel sad. For Normals, the documentary life is real life. Normals are fascinating creatures. They glance at Charlie with that fascinated face, but Normals are far more interesting than Charlie — with only a void where something else could be.

This is why Normals are the object of Charlie’s gaze. She sometimes chooses to turn up the volume, to sit close to the screen and prepare a box of tissues. Charlie chooses when to sink more deeply into the film of her life. But most of the time, she’s the audience and everyone else is a pawn. Sometimes she’s the director. Charlie directs the lighting of any scene, ranging between a soft, ambient blush to dramatic chiarascuro.

Honestly, which side of the camera would you choose? Happiness comes easy to Normals, but can anyone be truly okay as Charlie’s puppet?

Charlie does know one thing for sure about those lemons she left in Willow’s letterbox. On a scale of one to ten, it’s negative twenty-eight on the scale of evil acts.

“No one means any harm,” Charlie tells Willow. Then she realises she’d better ask for details. Charlie asks what the notes say.

Willow takes over. She’s crying as she talks. “They open with ‘Dear Willow’. Then there’s something about lemonade. They sign off with ‘Love, Life’.”

“What about lemonade, exactly?”

“Ingredients. Instructions to make some. That kind of thing.”

Scarlett has a theory. “I still reckon it’s Corey Brasher. ‘Make lemonade’. That’s a spin on ‘Make me a cheese sandwich.’ I know that fool’s terrible hand lettering when I see it.”

“Well,” Charlie says, “someone better confront Corey Brasher.”

That’s a rash thing to suggest because, actually, Charlie doesn’t need Corey queried about lemons. Surely people who are bad at lying are equally easy to read when they’re telling the actual truth. And ‘easy-to-read’ describes Corey to a tee.

“Oh, they’ve all been confronted.” Scarlett sounds resigned. “Look, Charlie, we know you’re friendly with those guys, but don’t say anything, okay? We’ve been advised to keep it on the down low. ‘The truth will reveal itself in time’.”

Charlie recognises that quote from Miss Berry’s wholeclass lecture. Scarlett likes to parrot teachers, and their English teacher in particular. She’ll probably be one someday.

Then Scarlett reads the look on Charlie’s face, gets her wrong as usual, and tells Charlie not to worry. “Willow’s dad phoned school about it, no one’s been threatened, everything’s under control.”

“Your dad phoned who, now?” Charlie’s heartrate is up. Those lemons in Willow’s letterbox have set off a chain of unintended consequences, all because everyone’s taking fruit way too seriously these days. This is more exciting than she thought it’d get. And she didn’t even have to do much.

Scarlett takes a deep breath and fills Charlie in. Apparently, Willow confided to Scarlett, Scarlett took it to Miss Berry, Miss Berry talked to our head of year, who talked to Corey Brasher and co. By all accounts, Corey Brasher came across as believably baffled.

Charlie was right about Corey’s transparency, then.

“So it’s not Corey Brasher,” Charlie is forced to say. Surely Willow secretly knows this is Charlie. She must. Dumb as she is, she must. Without much of a detour, Charlie walks past her house every dam day.

“That’s what Miss Berry said too,” Scarlett says. “They ‘can’t organise themselves out of a paper bag’. The daily lemon is a dedicated, long-running campaign. Whoever’s doing this, they have disturbing stickability.”

Charlie has learned through her counselling sessions that short-term pleasure can land her in hot water, and that deferred gratification can confer longer-lasting dividends.

Charlie has also suffered through roleplay in which she puts herself in someone else’s shoes. So Charlie knows what this must mean for Willow. If Willow noticed anything at all, she thought it was only the Cheese Boys who hate her annoying guts, while actually just wanting her attention. But now she knows it’s proper spite. She knows it goes wider than them.

“Don’t worry, Willow,” Charlie says. “It’s only lemons.”Charlie thinks she should probably say something kinder, in a softer tone. “Let’s not talk about it.”

Scarlett lowers her voice. “Keep your ear to the ground,” she tells me. “Let us know if anyone cracks further lemon jokes.”

Charlie wants to tell them it was all her. If she told the story really well, it might even sound funny. She wants to see how Nice people react. It’s kind of like her own mini science experiment. A psychological one. Except then it’d all be over. She would not have Scarlett as her ally anymore. And she does come in handy. Charlotte, Scarlett… teachers conflate them, and Scarlett is a bastion of morality. If that’s not good cover, Charlie doesn’t know what is.

Here’s what Charlie does say: “I don’t think it’s anyone, really.”

What she means is, it’s no one worth worrying about.

But Willow’s eyes grow wide and she nods in strong agreement. “I don’t think it’s anyone, either,” she says. “I don’t think it’s anyone at all.”

Scarlett groans. “We’ve been over this. Tell her, Charlie. You don’t believe in woo-woo. Talk some sense into the girl.”

“It’s not woo-woo.” Then Willow looks right at Charlie, and busts out with the wildest take. “Don’t ask me to explain it,” she whispers, “but every time I get a lemon, something bad happens. I get a lemon, forget my lunch. I get a lemon, lose my favourite pen. Then the beak snapped off my ornamental owl, and things went missing from my room…” Willow has kept a mental list of all the bad things in her life. Just when I think she’s come to the end she says, “My great-gran passed away.”

Willow always did excel at wacky mental gymnastics.

Scarlett tries to say something reassuring — something scientific about cause and effect and old age — but Willow needs to finish.

“Then I got a due date wrong and then I lost my temper in class—”

Scarlett snaps her salad box shut. “Classic confirmation bias. I still think your parents should set up a security cam.”

Fortunately for Charlie, no one has done that yet. Charlie is not reckless. All along she has been scanning the Jensen front yard and veranda for new installations.