“Lamb to the Slaughter” is one of Roald Dahl’s most widely read short stories, studied in high school English classes around the English speaking world. In this post I take a close look at the structure from a writing point of view. Why has this story found such wide love? What appeals?

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “Lamb to the Slaughter” was broadcast Christmas 2009.

STORY STRUCTURE OF LAMB TO THE SLAUGHTER

The ‘main character’ of this short story isn’t clear because this is a story about a scenario, and the characters are required in order to carry out the scenario. The characters are archetypes. However, the story opens with Mary Maloney. We are encouraged to identify with Mary Maloney, and it is Mary who goes through an extensive range of emotions. We end with a conspiratorial relationship with Mary.

SHORTCOMING IN LAMB TO THE SLAUGHTER

Mary Maloney is childlike, as housewives of the mid 20th century often were. Mary is economically and emotionally vulnerable, and she is extra vulnerable because she is six months pregnant. She is unable to simply move on from this relationship, or get a job. Re-partnering will be hard for her, too. This situation encourages the reader to empathise with her plight, even if we don’t agree with her way of dealing with things. Also, readers are like ducklings and we tend to empathise with the character first shown to us. If Dahl had instead described the policeman’s arrival home, starting with him leaving work, turning the difficult situation over in his mind, we might have empathised with him instead.

Mary also has a Virgin Mary association — we don’t think of murderers when we think of ‘Mary’. I guess that’s why when we do get a murderer named Mary, we are intrigued by the story and it becomes lore.

DESIRE

Mary’s desires seem to be right there on the page: She is lonely during the day and home with no adult company, waiting for a scrap of human interaction from her husband after spending the entire day preparing the home for his arrival. But this interaction with her husband is her surface level desire, and points to a deeper desire: to assuage her utter loneliness. This is especially well set up by Dahl, because the very worst thing that could happen to Mary is to be left all alone.

OPPONENT

A simple web: Mary wants to remain married to her husband; her husband wants to leave her for another woman (we guess). Because their desires are in direct conflict, this makes them opponents. Later, the dead husband’s colleagues arrive. Part of what makes this story work: The husband was himself a policeman, so when his colleagues arrive to replace him as new opponents, these men seem like basically the same person to Mary.

Note also the writing trick employed by Dahl — he leaves the exact words of the break-up conversation off the page, instead giving us enough clues to work it out ourselves. This works partly because Mary is so blown-away by this revelation that she wouldn’t be able to take in all the words. This aligns the reader with Mary. It also works for another reason: Break-up sequences are pretty boring for most readers, who have seen the exact same conversation played out time and again in stories. It’s very hard to write a break up scene with any kind of originality, so Dahl just skips it, and trusts us to fill in those blanks. Also, the break-up is not a big part of the story. The Story = what comes after.

A question we might ask ourselves when writing short stories: Which parts of this story have been done so many times before that I can easily skip them? Narrative summary is a useful tool, especially in short stories.

PLAN

When a character snaps and does something crazy, you can’t really argue that there was a plan. Mary only makes her plan later: She didn’t plan to kill her husband, but she does plan to get out of it. She will visit the grocer, then return home to ‘discover him dead’, then get rid of the murder weapon by acting like a grieving wife in shock, then she will encourage the policemen to eat the lamb. This plays out with what I like to call a ‘heist plot’. I just mean that the reader doesn’t know what Mary’s going to do until she does it. Dahl puts the reader in audience inferior position. Reader satisfaction derives from seeing Mary carry out her plan and then get away with it.

Be wary of writing characters who just snap and do something crazy. I have heard judges of short story competitions complain that they see too many of those — perhaps writers are hoping to emulate Lamb to the Slaughter. Why does it work for Dahl? Because a woman snapping is not the story. Stories which end with a character snapping don’t work because:

- It’s generally unbelievable that people just snap — people who commit these crimes in real life have a history of violence. And in a short story you don’t have time to get into someone’s entire history, so it’s going to feel unfinished.

- It works here because Lamb to the Slaughter is basically melodrama. It’s written with a wry, tongue-in-cheek smile right from the start, and even Mary’s giggling is comical and over-the-top. Lamb to the Slaughter is written in the tall tale tradition.

- If a writer concludes a story by having their main character just snap and do something murderous, it feels like the writer can’t think of a more interesting way to finish the story off. ‘And then she killed him’ is akin to ‘And then she woke up and it was all a dream.’

- There is already a long history of tales which end in sudden death. Take Fitcher’s Bird, a tale collected by the Brothers Grimm. The final sentence: ‘And since nobody could get out, they were all burned to death’.

BIG STRUGGLE

It’d be easy to think the bit where Mary slaughters her husband is ‘the big struggle scene’, but it’s not, really. There’s no big struggle in that. She comes at him from behind. For storytelling purposes, the big struggle scene comes after a plan has been concocted and mostly carried out. Thus, the ‘big struggle scene’ in this story comprises the sequence in which the policemen hum and ha about whether or not they should go ahead an eat the lamb, with Mary encouraging them to eat. Mary wins that big struggle of words and manners.

ANAGNORISIS

The story ends when Mary giggles to herself from the next room. She has concluded she’s getting away with murder.

NEW SITUATION

The new situation phase is cut off in this story — as it is in many short stories — and left for the reader to extrapolate. We may also conclude that Mary has gotten away with murder.

LITERARY INFLUENCES ON LAMB TO THE SLAUGHTER

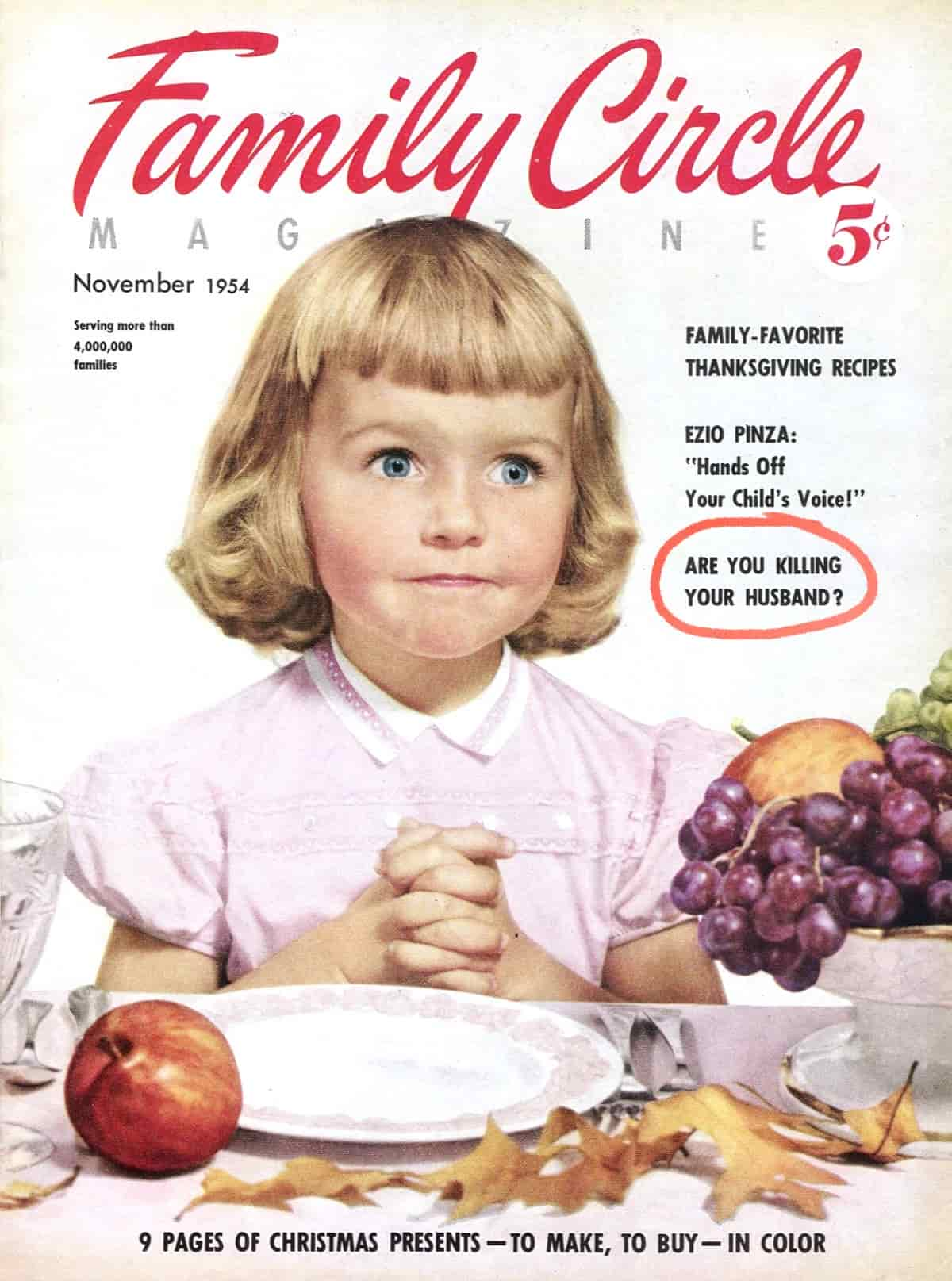

Dahl wasn’t the first to shock readers with a cannibalistic yet strangely genteel scene involving a character eating its own kind in a story about duplicity.

The Juniper Tree was one of the tales collected by the Grimm Brothers. In a patrilineal culture, a mother is angry that she and her daughter will inherit nothing while her husband’s son will inherit all. She is soon so overcome with anger that she is possessed by the devil, and eventually shuts the boy in a trunk, luring him with apples. The boy is decapitated. The woman tries to tie it back on with a neckerchief, but then the daughter accidentally knocks it off and believes she’s the one who killed him. The boy ends up in a stew. The father comes home, asks where the son is, and is told that the boy has gone away to stay with relatives for six weeks. The man eats the delicious stew — which he feels is part of him somehow — and throws his son’s bones under the table, which makes me wonder if that’s what men did in those days. (It reminds me of modern casino culture, in which big gamblers — mostly men — simply piss on the casino carpet rather than leave their stations to visit the toilet.) It’s the daughter’s job to tidy up after him. She collects the bones in a silk cloth and buries them under the juniper tree. The boy is reborn into the shape of a bird and the story goes on from there. The boy/bird eventually exacts revenge and kills his mother figure for killing his human form and feeding his flesh to his father. The mother is therefore punished, for letting herself become so angry and scared about becoming old and homeless and letting herself go crazy. Presumably, her daughter escapes this kind of crazy with her youth, and lack of understanding about how the world works. The sister doesn’t know that she, too, may become homeless — she is young and is likely to marry. So the inheritance thing probably doesn’t affect her.

Roald Dahl had a different relationship with retribution. Matilda is an entire middle grade novel made of revenge sequences against her terrible parents and Miss Trunchbull. Dahl certainly enjoyed pranks and tricks and loved to let his characters get away with bad stuff. Lamb To The Slaughter is another revenge tale, but unlike in The Juniper Tree, Dahl’s murdering woman is never punished. Dahl leaves his readers to imagine that her husband fully deserved to die.

The Juniper Tree was collected by the Grimms, but originally written down (in low German) by a painter called Philipp Otto Runge. There’s an entire family of tales in which one parent kills a child, the other eats him. (It’s usually a boy who is eaten.) Though these tales weren’t originally for children, food and death have become linked over the course of children’s literature.

Since sex and death (violence) are intertwined in mainstream stories, it is food and death which are intertwined in stories for children.

for more on that, see Food and Sex in Children’s Literature

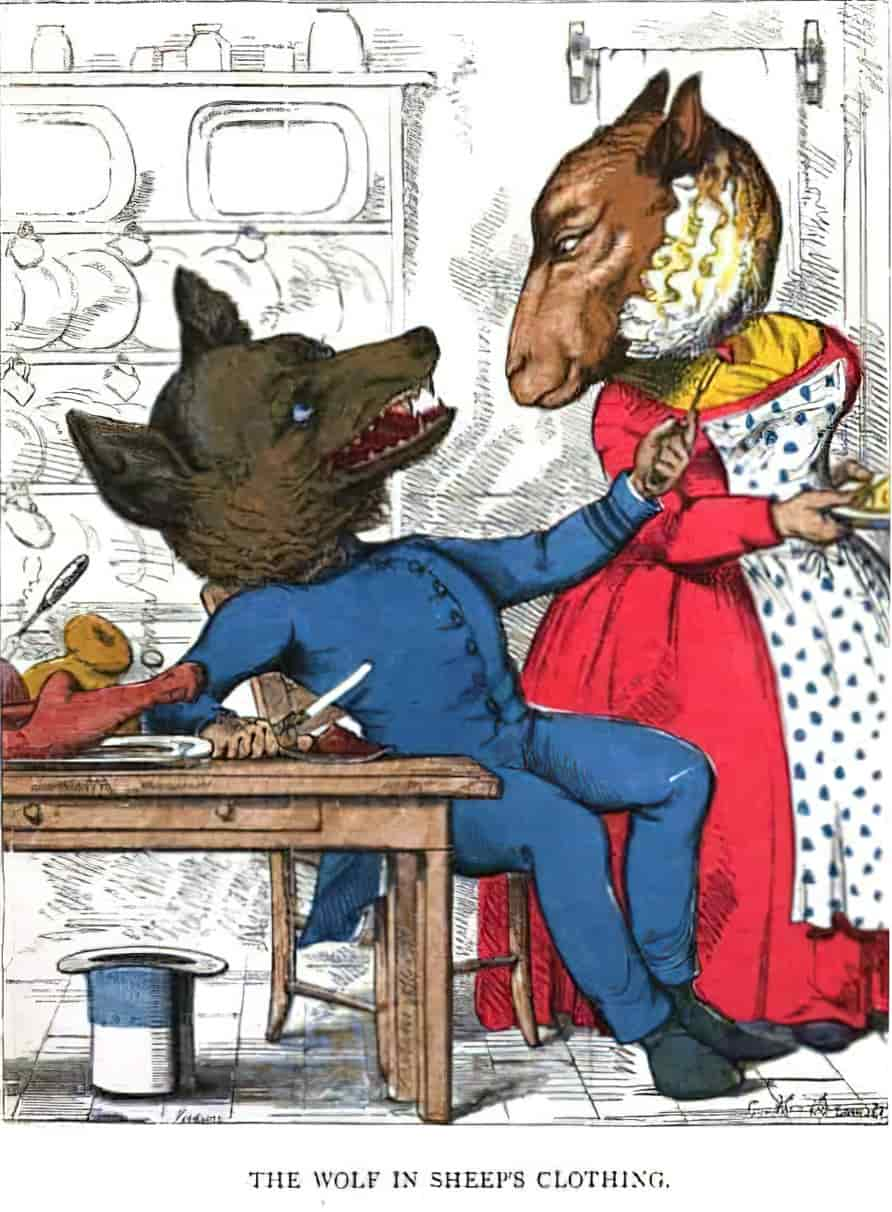

Later, in 1857 the Fables of Aesop were translated into Human Nature. Aesop’s Fables had been published many times before this, but until now, readers had not seen them illustrated so adeptly by a well-known comic illustrator of the time: Charles Bennett (1828-1867).

Bennett dressed Aesop’s animals completely and gave them a contemporary mid 1800s setting. The characters are Victorian Londoners, but with animal heads. In order to find the illustrations funny the reader needs to know something about that particular social milieu. It was funny that Bennet turned the Fox in ‘The Fox and the Crow’ into a philanderer and the Crow into a rich widow, for example. Animals dressed in clothes appeal to children and so Grimm’s fairytales and Aesop’s fables became stories for the whole family, and eventually considered ‘children’s stories’. Likewise, Lamb to the Slaughter is not a children’s story, but when I taught high school English, this short story was studied by year elevens.

Aesop’s Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing is dressed as a policeman, taking supper in the basement with the cook, who is a sheep. They are ominously dining on a leg of lamb, and I wouldn’t mind betting Roald Dahl read the Bennett version of the Aesop’s Fables at some point, perhaps during his childhood. I’m sure Bennett’s comic illustrations would have appealed to Roald Dahl anyhow, whose own work was illustrated by famous British comic illustrator of the late 20th century and beyond, Sir Quentin Blake.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST “LAMB TO THE SLAUGHTER”

If you’re a teacher who’s grown a bit tired of teaching Roald Dahl year after year, and can also see the slightly problematic ideology in his work, or if you’re after a compare and contrast story, short fiction from the Shirley Jackson collection Dark Tales is a good option.

Dark Tales includes the following stories:

- “The Possibility of Evil” — An old woman isn’t so harmless after all. At first she documents the stresses her neighbours have been under but then we learn she’s been sending them all horrible letters. Despite her horribleness, Shirley Jackson is able to encourage reader empathy with the old lady.

- “Louisa, Please Come Home” — This 1948 story is the most widely anthologised tale from this collection, about a young woman who up sticks and leaves home one day. Her family put out a broadcast for her return every single year. One day she decides to return. But when she returns, her family no longer recognise her.

- “Paranoia” — A businessman leaves his office and stops to buy chocolates for his wife’s birthday, with plans to take her to a show. But on the way home he thinks someone is stalking him.

- “The Honeymoon of Mrs Smith” — A young bride accepts her imminent murder because she doesn’t want to make a fuss. Compare and contrast with Margot Lanagan’s “Singing My Sister Down”.

- “The Story We Used to Tell” — A woman is staying at a female friend’s house when the friend disappears. The woman sees the friend trapped in a picture (an old painting of the friend’s house) on the friend’s bedroom wall and, touching it, is herself sucked into it.

- “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” — A mean girl torments adults for fun.

- “Jack the Ripper” — A kind passer-by saves a drunk girl sleeping on the street and brings her home.

- “The Beautiful Stranger” — A woman becomes convinced that a skilled pretender has taken the place of her real husband. We don’t know if the woman is crazy or clever, which serves as commentary on how women are frequently coded as crazy when in fact they are acting logically given their own circumstances.

- “All She Said Was Yes” — A teenager Wednesday Addams character foresees tragic events that take place in the future.

- “What a Thought“— A catalogue of a wife’s thoughts, in which she experiences the urgte to murder her own husband.

- “The Bus” — Available online at The Saturday Evening Post.

- “Family Treasures” — Introverted Anne’s sophomore year at college after her mother has died.

- “A Visit” a.k.a. “The Lovely House” in other anthologies — School-friends Margaret and Carla arrive at Carla’s home, where Margaret is to spend the summer months. Together Margaret and Carla explore the labyrinthine layout of the house.

- “The Good Wife” — A jealous husband incarcerates his wife. Has a twist ending in which the husband is even more of a monster than we could have imagined at the beginning. The wife attempts appeasement (a common response to trauma and abuse).

- “The Man in the Woods” — A young man named Christopher inexplicably leaves his life as a college student and finds himself walking deeper into a forest, where he comes across a mysterious stone cottage. Strong fairytale vibes.

- “Home” — About female passivity, how women are rendered passive by the dominant culture. The woman in this story has a ghostly experience when she comes across an old woman and a boy in the pouring rain near her house. She knows not to talk about it, even though the experience almost killed her.

- “The Summer People” — A couple who normally spend their summers up at their lake house decide to extend their stay into the autumn.

“Dark Flowers” by Alice Walker is also sometimes taught instead of/alongside “Lamb To The Slaughter”.

For Year 9s, “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe is another story with emphasis on the murderer rather than the victim.

“The Adventure of the Speckled Band” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is an oldie but a goodie and is used with Year 7.

“Ruthless” by William de Mille has a similar theme to “Lamb To The Slaughter” (murder, morality, justice) and also has great characterisation.

“A Vendetta” by Guy de Maupassant is another great compare and contrast for “Lamb To The Slaughter”.

FURTHER RESOURCES

In this episode, we discuss “Lamb to the Slaughter” by Roald Dahl. What can we learn from this classic story? How versatile can a story’s point of view be? How can subtle shifts of point of view change how we see a character moment to moment? What is the value of a great story idea? How can we use indirect dialogue?

Why Is This Good? podcast

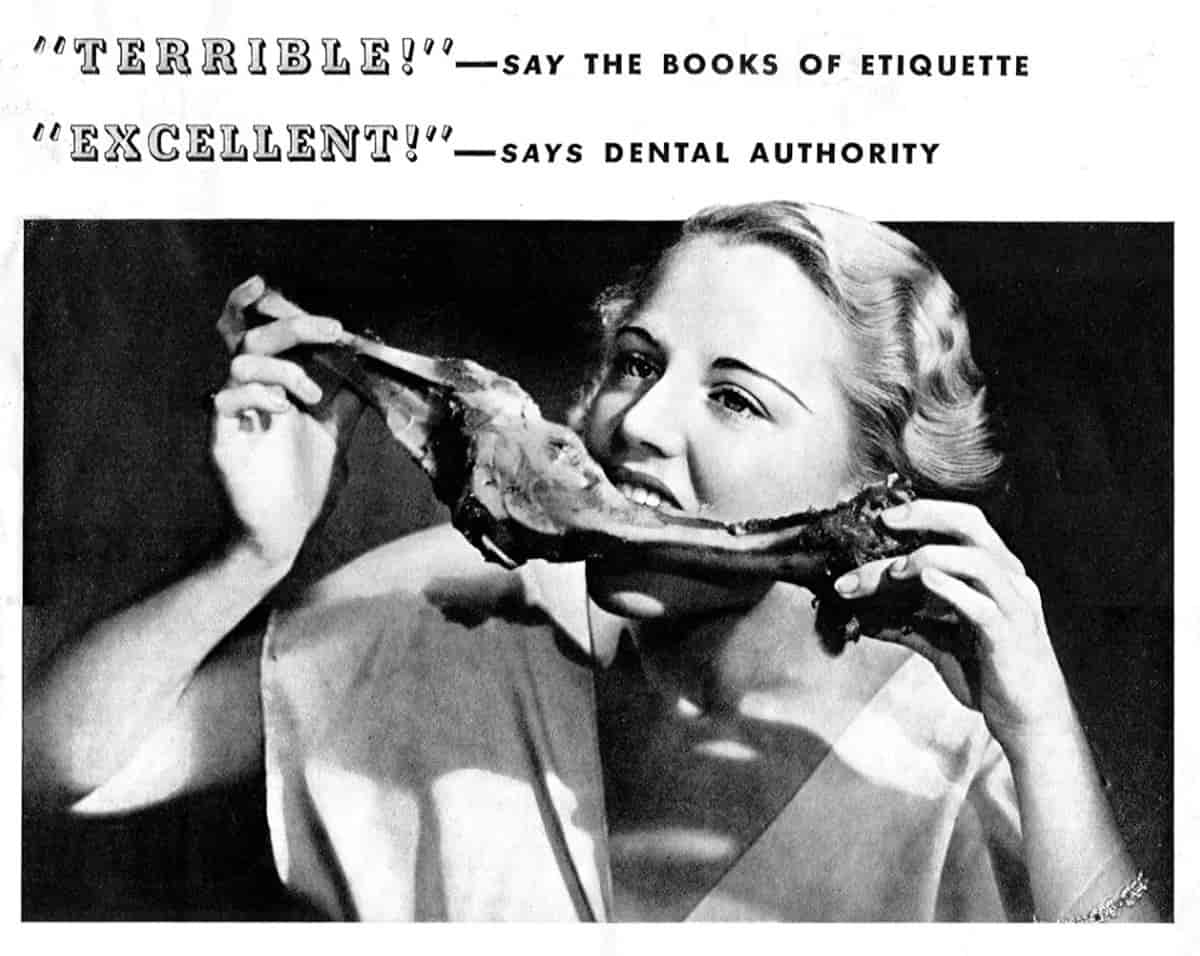

This old British pork ad has gone viral because it’s ‘easily the most sinister advert ever made’ from The Poke: Time Well Wasted