**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

Well, it’s Labor Day here in Australia, that time of year when smartphones decide we must rise and shine a full hour earlier due to that sacrilegious custom called “Daylight Savings”. Why not enjoy an Alice Munro short story with that extra hour of daylight I now enjoy at the other end of the day?

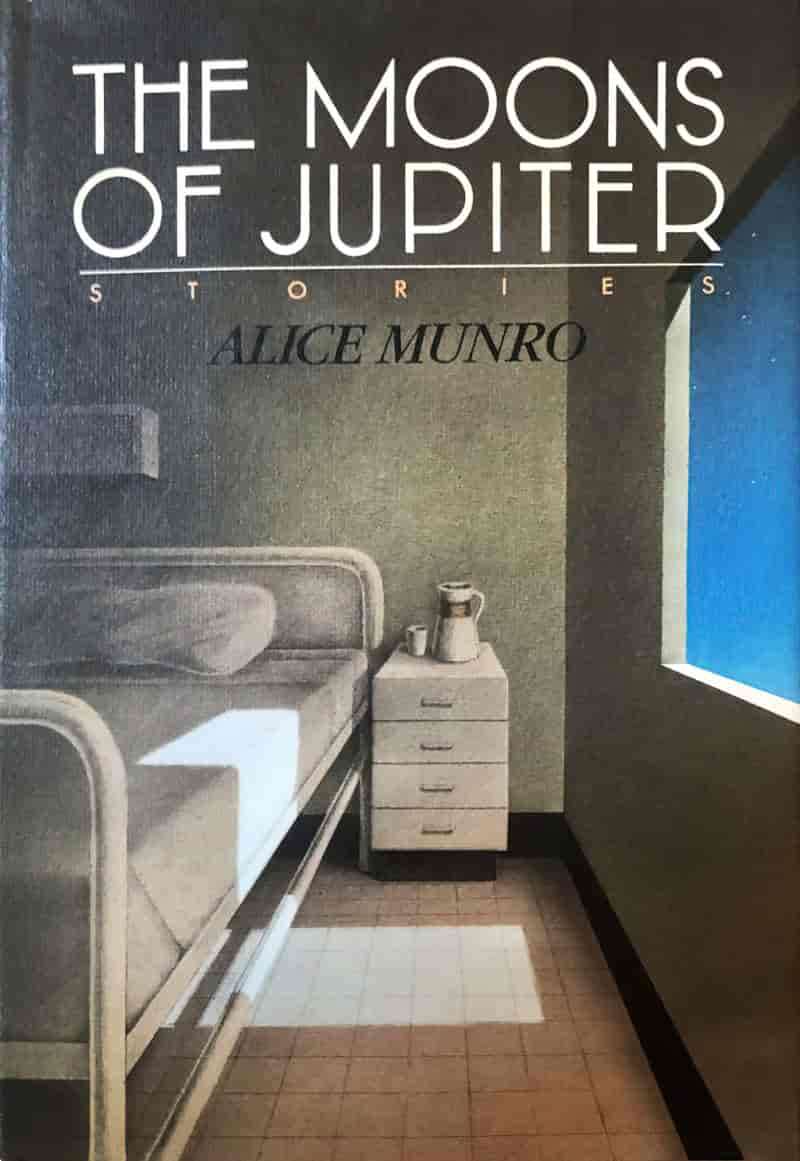

“Labor Day Dinner” was first published in the September 28, 1981 edition of The New Yorker. Find it also in Munro’s The Moons of Jupiter collection (1984).

A woman has moved to the country with a younger man who is revealed to be a narcissist. Her epiphany over dinner? She can live with him so long as she pulls back emotionally. By the time they are home that night, readers will understand that her emotional state matches the dilapidated house: Roberta can only feel at home with George if she deadens something in herself.

LABOUR DAY AS END OF SUMMER

Labour Day in Canada is marked as a statutory public holiday on the first Monday in September. End of summer. In this region of Australia, Labour Day is the first Monday in October and marks the beginning of summer. Since seasonality is so often symbolic in stories, I feel from the outset that this is important. Stories which take place at the end of summer are so often melancholy.

Note, too, that Munro chose to write this story in present tense, which isn’t usual for her. (Why write in present tense? For many reasons.)

MUNRO’S MASTERFUL OPENING PARAGRAPH

Let’s take a moment to admire this opening paragraph, because Munro establishes so much, so succinctly:

Just before six o’clock in the evening, George and Roberta and Angela and Eva get out of George’s pickup truck — he traded his car for a pickup when he moved to the country — and walk across Valerie’s front yard, under the shade of two aloof and splendid elm trees that have been expensively preserved. Valerie says those trees cost her a trip to Europe. The grass underneath them has been kept green all summer, and is bordered by fiery dahlias. The house is of pale-red brick, and around the doors and windows there is a decorative outline of lighter-colored bricks, originally white. This style is often found in Grey County; perhaps it was a specialty of one of the early builders.

opening to “Labor Day Dinner”

- Time, county, season included in a description of a house;

- We know a fairly wealthy woman lives there and we’ve been primed for someone a little eccentric given her care for those two elms, and that she would measure the cost of tree preservation in ‘trips to Europe’.

- The names of the characters in the family, plus the hint that George is a more recent addition (‘he‘ traded his car, not ‘they‘). The use of ‘and’ between every single member of the family suggests they walk across the lawn separately, psychically removed from each other. (Sure enough, we will soon learn of the ‘murderous silence’ between George and Roberta.)

- George used to live in the city — he is out of his natural environment.

- The symbolism has been set up with the grass underneath the elms the only parts of lawn not dead. Also, dahlias are known for their ability to bloom after many other flowers have died. Likewise, a decorative outline of bricks on the house were ‘originally white’. This story must be about to contrast how things are compared to how they used to be, or oases of life where all around is dead, that sort of thing.

- A connection to the long past of the area with mention of ‘early builders’.

“LABOR DAY DINNER” IN A NUTSHELL

- Roberta, George and Roberta’s daughters all go to a party at Valerie’s house.

- Roberta and George have not been getting along. They went out the night before and got drunk together at a ‘lounge’ which attracts wealthy conservatives, but this didn’t work to patch up the relationship.

- But they are at their friend Valerie’s, they put on a show of civility as soon as they arrive.

- As a favour to Valerie (who introduced them to each other originally), George goes outside to cut Valerie’s grass and burdocks with a scythe he has brought with him. Although he complains that Roberta and her daughter don’t help with the work at home, he is happy to perform it here while the women relax.

- With George out of earshot, Roberta tries to explain to her friend Valerie what she loves about George. She is trying to persuade herself of his goodness.

- But Valerie feels quite differently about the role of love in general. She cannot bolster Roberta’s more idealised image of George, and doesn’t believe love improves anything.

- Over dinner, the young people banter about various things like love, arches in architecture, acid rain, the environment.

- Roberta feels herself getting drunker and realises indifference will save her when it comes to dealing with George (who is revealed to be a narcissist). Indifference is the best way to deal with a narcissist, because narcissists are never going to change. (Personality styles are enduring.)

- On the drive home with George, the family narrowly avoids collision with a truck with no lights on. This truck seems to appear from nowhere.

- The truck swerves off the road as quickly as it arrived.

- This puts Roberta and George in a strange, disoriented mood, punctuated by the younger daughter asking if they’re dead, because aren’t they home?

SETTING OF “LABOR DAY DINNER”

This story is set in Grey County.

Grey County is a county of the Canadian province of Ontario. The county seat is in Owen Sound. It is located in the subregion of Southern Ontario named Southwestern Ontario. Grey County is also a part of the Georgian Triangle. At the time of the Canada 2016 Census the population of the county was 93,830.

Grey County, Wikipedia

Two hours, three miles apart, are separated by fields of wilting corn.

“LABOR DAY DINNER” CHARACTERS

ROBERTA

Roberta is a 43-year-old woman with two daughters with a man Munro still refers to as her ‘husband’. This husband, called Andrew, lives in Halifax and is in the Navy. (Halifax is on the East Coast of Canada, in the Maritime province of Nova Scotia.)

She has previously illustrated a few picture books, which partly explains what she and George have in common. (George is a former art teacher.)

These days Roberta lives in a very different part of Canada with a new man called George. George is a little younger than Roberta, in his thirties.

They have lived for one year on George’s farm, which is gradually revealed to be dilapidated. She is overwhelmed by the task of managing this farmhouse and farm, which requires a lot of, ahem, labour. Roberta had meant to illustrate more picture books after moving to the country and sit on cushions instead of chairs in a white room. She has had no time to do any illustrating.

Nor has she suddenly morphed into an excellent farmer. While George has done most of the essential maintenance labour around his own property, Roberta has mostly ‘swept and cooked’. While cooking and housework is a job in its own right, it does not attract the prestige of the fixing-up work. This is a phenomenon that’s far bigger than Roberta, and she currently feels like a failure.

When the point of view shifts to George, readers learn that although George has admitted that Roberta does some work, she’s done nothing to earn them money. (Subtext reading: If it doesn’t earn money, it doesn’t count as work.)

Roberta has chosen to wear dark glasses to this dinner because:

she has taken to weeping in spurts, never at the really bad times but in between; the spurts as as unbidden as sneezes.

“Labor Day Dinner”

What other people knew about George already seemed inessential to her. She was full of alarm and delight. Being in love was nothing she had counted on. The most she’d hoped for was a life like Valerie’s.

“Labor Day Dinner”

Readers can see that Roberta — like George’s farm house — is a former shell of herself. She has lost her passion for illustration and although she has kept busy preserving and cooking, ‘she can feel her own claims shrinking’. This is what happens when you’re in a relationship with a narcissist.

Over dinner, Roberta takes notes from the young women at the same table who are shown to have a much better handle on the character of George. Indirectly, Roberta learns from them and knows that only her genuine indifference will work if she means to stay with George.

At the end of the story, the four of them arrive home after a near-death experience. When Eva uses ‘dead’ and ‘home’ in the same sentence, Alice Munro is tying up the themes and Roberta’s new reality: So long as she ‘plays dead’ (emotionally numb) she’ll be able to build a home with George. Indifference is the only way to attract him back to her.

Of course, this is no way to live. But many people are stuck in that kind of relationship.

GEORGE

Let’s call Roberta’s narcissistic partner George. That’s because his name is George.

George is the son of Hungarian immigrants originally from a town north of here. We don’t exactly love him though, right? He appears to be jovial but is in fact a harsh, no-nonsense man, which can be tricky for anyone who doesn’t recognise his type.

He is emotionally immature and can’t understand or accept Roberta’s tearfulness lately. He had taken her for an independent and hardworking woman when he met her and, like Uncle Benny of “Flats Road“, or Mary Bee Cuddy of The Homesman, or indeed like any farming partnership of yore, George requires a spouse partly to be a work horse. But narcissistic misogynists deliberately target independent and hardworking women with the specific goal of breaking them down.

His former wife, ‘a jittery, well-dressed woman’ and daughter of a gynecologist was killed in a plane crash in Florida. However, the couple were already divorced by that stage. (Note how much detail Alice Munro gives us even regarding characters who never make it directly onto the stage. This is partly what makes her short stories feel like novels.)

[George is] the sort of person who would know what to do in a street fight but doesn’t know how to swim. […] I think he drops women rather hard.

Valerie’s assessment of George in “Labor Day Dinner”

Despite not being a parent himself, George has set ideas about parenting and thinks Roberta lets her teenage daughters get away with doing too little.

But Alice Munro gives the guy nuance — a Munro speciality. Even the bad guys are rounded. On this particular evening, at least, he accommodates Roberta’s daughters wish to dress up when ordinarily he might disapprove:

Roberta was a little nervous, but she was relieved to see him sympathetic and indulgent about the very things — self dramatization, self-display — that she had expected would annoy him. She herself has given up wearing long skirts and caftans because of what he has said about disliking the sight of women trailing around in such garments, which announce to him, he says, not only a woman’s intention of doing no serious work but her persistent wish to be admired and courted. This is a wish George has no patience with and has spent some energy, throughout his adult life, in thwarting.

“Labor Day Dinner”

(The reader might deduce that George goes against his partner’s instructions to her own daughters only as a form of retribution and malice, not because he really believes it would be ‘ignominious for them to have to huddle down on the floor [of the cab] in their finery’.

He then drives to Roberta’s friend’s house so very slowly it feels like a ‘funereal pace’. He’s been in a sulk since the morning of the day before. George is thereby depicted as a passive-aggressive arse. We can also see that Roberta, herself, has not got the full measure of him. (‘Roberta thought that after speaking in such a friendly way to the girls…’)

Then we find out he’s emotionally abusive, or what we would now call coercively controlling. Already, just one year into the relationship, he is controlling what Roberta wears. Alice Munro understands coercive control at a deep level. We see the depth of her understanding in a 1998 story, “Queenie“. Remember, Munro was writing about these relationship dynamics before there was wider understanding of them. (By my reckoning, the word ‘gaslighting’ has really only been in popular usage for about 10-15 years.)

IS GEORGE A NARCISSIST?

Although I feel the word ‘narcissist’ is too often misapplied when ‘abuser’ would do. That said, narcissism expert Dr Ramani has said that about one in five people have a narcissistic personality style. So I don’t feel it’s a stretch when many stories I read seem to include at least one character with a narcissistic personality style.

Whereas Roberta sees both her daughters as children, who should be allowed to behave as children on summer holiday, George also sees them as children but his ideas about ideal childhood are different. Roberta’s daughters are children because they fail to see jobs that need doing right under their noses. All of the characters around him are potential sites of labour. If only he could wrangle them. (Yet when he is at Valerie’s house he shows himself to be a good man by scything her paddock weeds for her.) He despises the cat because, as we all know, cats cannot be wrangled. A cat is of no use to a narcissist. (We might say cats are themselves narcissists…)

He usually joked with the girls no matter what he felt like. Rough joking was his habit, and it had been hugely successful in the classroom, where he had maintained a somewhat overdrawn, occasionally brutal, consistently entertaining character. He had done this with most of the other teachers as well, expressing his contempt for them so colorfully that they couldn’t believe he meant it.

[…]

And it was the boys, chiefly whom he learned to outmanoeuvre; boys were the threat in the class. The girls he never bothered much about, beyond some careful sparring with the sexy ones.

“Labor Day Dinner”

Don’t you just recognise this character? Ick and sheesh. I feel like I’ve met him. (Like Valerie, I’ve worked with him.)

As typical for grandiose narcissists, George is gregarious and appealing. Roberta seems to have told George early on how she found him ‘courageous, truthful’, and ‘without vanity’. Also according to George, the girls find him ‘highly amusing, which irks him sometimes and pleases him at other times’. (Only via Angela’s diary do we realise that’s not quite right.)

George has claimed much of the living area of his house for his own sculpting work. A man claims space without regard for what an adjacent woman might need. This is familiar territory for Alice Munro readers. We see an adolescent version of exactly this in “The Found Boat“, published in the 1970s. And like the inept historian in “Heirs of the Living Body”, George is not depicted as being particularly good at what he does. When 12-year-old Eva asks him about his half-finished projects, Munro encourages readers to wonder if he’s a serious artist: “Wooden doughnuts. Pop sculpt. A potato and a two-headed baby.”

PEOPLE WHO MOVE TO THE COUNTRY FOR SOME PEACE AND QUIET

George is not a lifelong farmer. He used to live in Toronto, but in his later years decided on what we these days call a ‘tree change’, trading his car for a pickup. It was a slight surprise to learn that he used to be an art teacher. We know that Roberta’s (former) husband is in the navy. Relying on my stereotyped image of a navy man (and of art teachers), it would seem Roberta went out of her way to partner up with someone completely different this time.

Here in Australia and New Zealand, so-called tree changers are somewhat notorious among intergenerational, career farmers for underestimating the work involved. They buy up ‘hobby farms’ after selling their overpriced city dwellings. Too often these hobby farmers fail to invest in expensive farm equipment they need, and expect neighbouring farmers to help them out without offering tools or skills in return.

Like Roberta, it is revealed that George had naïve ideas about what it would mean to live in the country and life self-sustainably. He had hoped to live cheaply with chickens and a vegetable garden to give himself time for wood sculpting. But as it turns out, living cheaply is itself a helluva lotta work.

Annie Proulx’s short fiction is frequently hard on city-slickers turned fake cowboy types. Note that Annie Proulx herself made a tree change herself, then wrote a 2011 memoir about how difficult it was to live in rural Wyoming on 640 acres of wetlands. It’s called Bird Cloud.

ROBERTA’S OLDER DAUGHTER ANGELA

The daughters live with their father in Halifax during term but it has been recently agreed that they will spend summers with Roberta and George in Grey County, Ontario.

They have arrived to the dinner party dressed in garments fashioned from drapery fabric in George’s attic.

Seventeen-year-old Angela is ’embarrassed by her recently acquired beauty’ and has a rich imaginative life in which she is the main character. Unlike George, who has a narcissistic personality style, Angela simply shows the typical narcissism of youth, a different thing*.

Angela is so self-interested she thinks everything revolves around her. That’s what happens when you become an adolescent.

Eva in “Labor Day Dinner”, describing what we call ‘the narcissism of youth’ (which is completely different from an enduring narcissistic personality style).

It’s easy to imagine the character Angela swanning around all summer, writing in a diary, doing gentle exercises in the morning. She also plays the piano.

*Narcissism does not equal ‘needs to be looked at’. Narcissists are most often men (despite popular belief) and are defined by an addiction to ‘narcissistic supply’. They treat people around them like puppets, and are by definition controlling. So when George enjoys not being looked at as he scythes, this doesn’t have any bearing on whether we might read him as narcissistic. However! The scythe works at a symbolic level. Tonight marks the start of the end of the best phase of a romantic relationship. (It’s only going downhill from here.)

MUNRO’S SOUNDTRACK

Like a good That Girl, she knows how to play an instrument. At Valerie’s there is a piano and Angela plays “Turkish March”, also known as “Rondo Alla Turca”. You’ve heard it. Then she plays “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik”. You’ve heard that one, too. Notice how neither of these songs is the slightest bit restful. Munro is providing a soundtrack to accompany the images you have in your head (assuming you’re phantasic, that is). This soundtrack juxtaposes against the peaceful women relaxing on the deck, but suits the vigourous movements of George in the yard with his scythe. This story is leading towards something darker. Later, at his mother’s request, David puts on Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, which is about as ominous as classical music gets. (John Williams’ Jaws theme must be somewhat inspired by Dvořák’s famous opening.) Ironically, hilariously, David regards the song as ‘syrupy’.

Also in line with her That Girl image, we are told Angela reads — or at least starts — many books, including the books one is supposed to read. (Note that Alice Munro preferred Emily of New Moon over Anne of Green Gables as a girl.)

In all of these ways, Angela feels to me like a 1990s version of the That Girl TikTok phenomenon. The only difference is, social media doesn’t exist, so she can’t broadcast her life to the world.

WAIT, WHAT IS ‘THAT GIRL’ AESTHETIC?

In this aesthetic, women, typically from college-aged to early thirties, show images and videos of being productive and engaging in self-care and self-betterment. They live regimented routines that encourage healthy eating, beauty rituals, fitness, organization, productivity in work and study, and mental healthcare in a clean and simple aesthetic.

Aesthetics Fandom

Here’s an example. That Girl life skirts dangerously close to orthorexia which extends beyond eating to every aspect of life — exercise, fashion, housework. She is known for: lemon water and smoothies, salads, gym sessions.

I also see similarities to advice dished out by Jordan Peterson to young men: Read more. Make your bed. These sensible nuggets of advice can obfuscate the reality that the movement itself is dangerous.

The That Girl may have a boyfriend who earns the money. There’s a big crossover with the Trad Wife movement, or the Stay At Home Girlfriend movement for slightly younger women.

Despite the fact that the That Girl already looks like a parody, parodies proliferate:

Basically, the That Girl is the unachievable ideal of a perfect feminine life. This archetype is by default thin, young, toned and light-skinned.

Munro’s short story reminds me that this archetype is not at all recent. It’s just that she got her name in the era of TikTok. She’s always been around. But as is pointed out in the following YouTube video breaking down the aesthetic, That Girl aesthetic is perfect for the social media age because her lifestyle is so Instagrammable.

A link is also drawn between That Girl aesthetic and Cottagecore. Roberta and George’s idealised life in the country is nothing if not cottage core. Valerie has shown them how it’s possible. (When George scythes Valerie’s lawn, he is surely imagining himself as owner and king of Valerie’s house. Alice Munro makes this easier to imagine by creating Valerie as a widow.)

DAUGHTER AS IDEAL LIFE

Note Angela’s symbolic name: Angel, perfection. The older of the two daughters is the beautiful teenage version of whatever Roberta idealises. When we see (from George’s point of view) Roberta admiring her daughter’s beauty on the deck that George built, this offers insight into what Roberta wants for herself. She craves youth and beauty and a type of perfection that can only come from being a teenager and having your parents (or at least your mother) run around after you doing the real work. This explains why she lets Angela get away with doing nothing useful. Vicariously, Roberta is living the country dream.

A SNAPSHOT OF A SH!TTY RELATIONSHIP

Via an idealised image of Angela on the deck, Alice Munro captures Roberta and George’s variety of unsupportive relationship perfectly:

Angela lowered her leg and said, “Greetings, Master!”

“I don’t see you bumping your head on the ground,” said George. He usually joked with the girls no matter what he felt like. Rough joking was his habit, and it had been hugely successful in the classroom, where he had maintained a somewhat overdrawn, occasionally brutal, consistently entertaining character. He had done this with most of the other teachers as well, expressing his contempt for them so colorfully that they could not believe he meant it.

Eva loved to act out any suggestion of this sort. She stretched herself full length on the deck and knocked her head hard on the boards.

“You’ll get a concussion,” Roberta said.

“No, I won’t. I’ll just give myself a lobotomy.”

“Labor Day Dinner” by Alice Munro

Munro could have chosen any number of different ways to capture the horrible relationship dynamic. She could have shown us another fight, another insult. But she chose to show us a scene in the sunlight, which looks at first glance like an idealised cottagecore moment.

Why? Because we need to see how Roberta herself can be duped into thinking this is all okay.

THE NARRATIVE ROLE OF ANGELA’S DIARY

But Angela is old enough to be charting a horrible change in her own mother. Via Angela’s diary, readers are shown the arc:

I have seen her change from a person I deeply respected into a person on the verge of being a nervous wreck. If this is love I want no part of it. He wants to enslave her and us all and she walks a tightrope trying to keep him from getting mad. She doesn’t enjoy anything and if you gave her the choice she would like best to lie down in a dark room with a cloth over her eyes and not see anybody or do anything. This is an intelligent woman who used to believe in freedom.

Angela’s diary, “Labor Day Dinner”

Note that Angela’s take on George is nowhere near as generous as George’s take — Munro has given us George’s take via a shift to close third person. As far as George is concerned, the girls both think he is highly amusing.

Readers can deduce that Angela is appeasing him. (Fight, flight, freeze, appease.)

ROBERTA’S YOUNGER DAUGHTER EVA

Twelve-year-old Eva has spent her summer catching small animals around George’s farm.

puritanical, outrageous — an acrobat, a parodist, an optimist, a disturber.

“Labor Day Dinner”

CHILD VERSUS YOUNG WOMAN

The difference between the two girls is expressed on the page by their different reaction to the barn:

If Angela sees the farm as a stage for herself, or sometimes as Nature — a begetter of thoughts and poems, to which she yields herself, wandering and dreaming — Eva sees it as a place to look for animals, with some of her attention left over for insects, minnows, rocks, and slugs.

“Labor Day Dinner”

This does not so much speak to a difference in personality style, but to the reality that one of them is in the throes of adolescent self-consciousness, the other still young enough to enjoy childhood pleasures.

VALERIE

A tall, wealthy widow with two adult children of her own. Smokes a lot but avoids red food colouring and takes vitamin pills to compensate.

Valerie makes what isn’t bearable interesting.

“Labor Day Dinner”

VALERIE’S ECCENTRICITY

It’s a bit limiting to describe Valerie as simply ‘an eccentric’. Her eccentricity is a performance.

Valerie never minds if she sounds silly; she will throw herself headlong into any conversation to turn it off its contentious course, to make people laugh and calm down.

“Labor Day Dinner”

She has recently cropped her hair short and concluded it makes her look like a goat but, in an unexpected reaction, she declares she loves goats. In this aspect she’s a reflection character for Roberta, who despises the part of ageing self which makes her still concerned about her appearance.

But really, Valerie is a sensible woman who has managed to get exactly what she wants. Moreover, she’s doing fine without a romantic partner. And when she doesn’t like someone, she has the maturity to understand what it is in herself that leads her to not liking them. (Cf. Kimberly.)

Valerie also lives in exactly the sort of ‘country house’ Roberta hoped to live in herself. After her husband died, Valerie moved permanently into this summer place. She’s been here for 15 years whereas George has only had his house and land for two. Whereas Valerie’s house is faded-red brick (suggesting substance and longevity), George’s rundown place is brick veneer.

A QUEER-LOOKING STICK

Andrew has said to Roberta that Valerie is ‘a queer-looking stick and utterly sexless’. Coincidentally, Roberta also refers to Andrew to Roberta as a ‘stick’. (Perhaps ‘stick’ is the go-to family insult?)

Valerie has known both Roberta and George for years, before they knew each other. In Toronto, she and George were on the staff at the same high school in Toronto. At that time, Valerie was the guidance counsellor. Roberta’s husband Andrew is her cousin. Roberta left Andrew in Halifax, went to stay with Roberta in Toronto and there she met George. Without Valerie, the pair wouldn’t be together. Valerie considers the couple her ‘creation’.

She lives just three miles away from George’s farm.

Valerie never meant to set her ex-cousin-in-law up with a teaching colleague She has told Roberta that watching the pair fall in love was ‘like watching an amaryllis. Astounding.’

Is Alice Munro making use of flower symbolism again? (Remember the hardy dahlias from the opening paragraph?)

What does the amaryllis symbolise?

This flower has a connection to myth.

- Amaryllis was the name of a maiden who fell in love with a shepherd called Alteo.

- Alteo was strong and handsome.

- He also really loved flowers.

- To win his affection, Amaryllis needed some pointers. So she went to the Oracle of Delphi for advice.

- The Oracle told her to stand outside Alteo’s house for 30 nights piercing her heart with a golden arrow.

- On the thirtieth night a flower grew from her blood. (Note that the amaryllis is blood red in colour.)

- She won Alteo’s love.

- The amaryllis flower now symbolises the love Amaryllis had for Alteo.

I remain skeptical about whether Alteo really fell for Amaryllis. It seems he had a thing for flowers. Likewise, as I read Alice Munro’s “Labor Day Dinner”, I don’t get the sense George really loves Roberta. He loves having Roberta around, but only so he can control her.

VALERIE AS AROMANTIC ARCHETYPE

Roberta’s lack of self-awareness comes through again when she suspects Valerie of not wanting to hear about love. It seems to me that Valerie doesn’t care one way or another about love; it is Roberta who can’t bear to be reminded of what it could look like, were she with a better man. Remember, Andrew has described Valerie as ‘sexless’ (perhaps he means aromantic). And as the asexual community keeps trying to tell the allosexuals, not everyone who is sexless is unhappy about it.

In Valerie’s company you do wonder sometimes what all the fuss is about. Valerie wonders. Her life and her presence, more than any opinion she expresses, remind you that love is not kind or honest and does not contribute to happiness in any reliable way.

“Labor Day Dinner” (and the best description of an aromantic mindset I’ve read yet in Alice Munro’s work).

(Note that in this paragraph Alice Munro subtly shifted the viewpoint character from Roberta to Valerie.)

The emboldened part of that quotation is Munro’s re-visioning of the following famous line from the Bible:

Love suffereth long, and is kind.

Corinthians 1:13 (quoted grandly by the insufferable George in Munro’s story)

What’s the connection? Lorrie Moore has this say:

That both ideas can be held simultaneously within the same narrative is part of the reason Munro’s work endures—its wholeness of vision, its complexity of feeling, its tolerance of mind. For the storyteller, the failure of love is irresistible in its drama, as is its brief happy madness, its comforts and vain griefs.

Lorrie Moore from the introduction

RUTH

Valerie’s 25-year-old daughter. Roberta’s daughter Angela adores her.

She has given up wanting to be an actress and is learning to teach disturbed children’ Her arms are full of goldenrod and Queen Anne’s lace and dahlias — weeds and flowers all mixed up together — and she throws them on the hall floor with a theatrical gesture and embraces the bombe.

“Labor Day Dinner”

As evidence that George really does have a way with straight adolescent girls, Ruth reveals she was ‘in love with’ George back when she was 13-14, when her mother was first getting to know him. Now she sees George for exactly who he is — “a closet conservative … which is confusing to everyone because he comes on like a raving radical”.

RUTH’S ROLE IN THE STORY

Ruth tells Angela she looks like the Bride of Lammermoor in her curtain-dress. Roberta doesn’t know who this is, but doesn’t get her question answered.

In Sir Walter Scott’s 1819 gothic novel “The Bride of Lammermoor,” the bride’s name is Lucy. The story tells the tragic love story of Lucy Ashton and Edgar Ravenswood, set in the Lammermuir Hills of Scotland. Lammermuir means ‘moorland of the lambs’ Lucy is portrayed as a beautiful young woman with fair features. Lucy and Edgar’s love is thwarted by family feuds and political intrigue, ultimately leading to a tragic outcome.

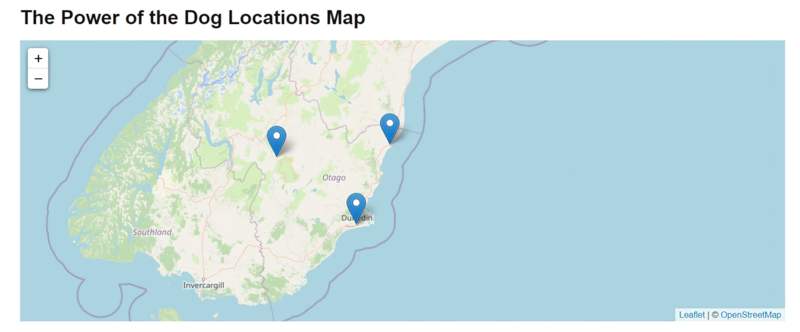

Scottish immigrants to my home country of New Zealand, using Walter Scott’s phonetic spelling, saw the rugged hills in Central Otago known in Māori as Te Papanui and renamed them the Lammermoor Range. If you’ve seen the film The Power of the Dog — set in Montana but filmed in Aotearoa New Zealand — the Lammermoors aren’t far from there.

Alice Munro is doing nothing by accident. So let’s ask why she might refer to a gothic novel. Let’s take a quick look at what happens to Lucy in Walter Scott’s 1819 story:

- Lucy Ashton and Edgar Ravenswood fall in love despite the bitter feud between their families.

- Lucy is initially engaged to Sir Edgar’s rival, Sir Arthur Bucklaw, as part of a political arrangement.

- Lucy’s brother, Henry Ashton, and her mother, Lady Ashton, conspire to force her into the marriage with Sir Arthur.

- Lucy becomes increasingly distressed. Her mental state deteriorates as the wedding day approaches.

- On the wedding night, Lucy suffers a mental breakdown and is found in a deranged state, leading to the collapse of the marriage ceremony.

- Lucy’s mental condition continues to worsen. She becomes convinced that her true love, Edgar Ravenswood, is dead.

- Tragedy strikes, and Lucy dies in a fit of madness, her health having been undermined by the stress and manipulation she endured.

- Edgar Ravenswood returns, only to discover the tragic fate of his beloved Lucy.

- The novel ends with a sense of melancholy and doom, as the feuding families are left to grapple with the consequences of their actions.

Note that when Ruth mentions Walter Scott’s novel, Roberta has never heard of it. Readers have already seen that Roberta (as typical for victims in a coercively controlling relationship) is not fully cognizant of the extent of her partner’s abuse. Readers familiar with the general thrust of Scott’s gothic novel will already see the general emotional thrust that Munro’s story will also likely take. (Or will she subvert expectations?)

DAVID

David is Valerie’s 21-year-old son. A history student. Tall and lean like his mother, ‘deliberate, low-voiced, never rash’.

It is noticeable that he lively, outspoken women defer to David in some ceremonial way, seeming to ask for the gesture of his protection, though protection itself is something they are not likely to need.

“Labour Day Dinner”

We don’t see much of David and Kimberly because Valerie sends them in to town to buy cigarettes, which she doesn’t actually need. She likes to enjoy the house without them occasionally. They come back in time for dinner where we get to know them a little more.

SONS AS CENTRAL TO THE FAMILY

I recently read two stories which feature an entire cast of family waiting in a house for the beloved and important son to arrive. The first is “A Visit” by Shirley Jackson which is of course a very different sort of narrative. Whereas Alice Munro’s story alludes to the gothic, Shirley Jackson’s story is very much written in the American gothic tradition. Another example is “An Ideal Family” by Katherine Mansfield.

Note that each of these examples has been written by a woman author. (Do male authors see this phenomenon happening in real time? I’m on the hunt for examples. My hunch is that women notice it more than men because men are so often the centre of it. It wasn’t a fish who discovered water.)

KIMBERLY

David’s girlfriend. We are shown Kimberly as Roberta would likely see her. Roberta herself has reached the age where looking ‘effortlessly beautiful’ is no longer a thing, so she notices the natural beauty of youth:

[Kimberly] is very clean and trim, in a white skirt and a short-sleeved pink shirt. She wears glasses and no makeup; her hair is short and straight and tidy, and a pleasant light-brown color.

“Labor Day Dinner”

Valerie complains in private to Roberta that Kimberly’s Christianity makes her feel mean. Notice how this is in stark contrast to the way Roberta idealises the luxurious That Girl life of her own daughter, Angela. Kimberly is a different kind of young and perfect, but Valerie’s having none of that. Valerie already has the lovely country house. She’s not living aspirationally. She’s simply busy with the task of living, not looking outwards. “There’s always something black,” she says, with a protective level of pessimism.

Kimberly’s Christianity comes in useful because she’s able to comment on George’s reference to love in the Bible. “I think that is a particular kind of love,” she counters.

It would seem this particular passage might be misinterpreted by abusers to mean ‘to love me truly is to put up with anything I throw at you’. But when I look at what Christians have to say about it, the passage doesn’t mean that at all.

He shows His love by His patience, which is a long-lasting patience. We are called not only to be patient but to suffer long. We are not to be patient with people’s sins, foibles, and shortcomings only as long as they cause us no pain.

Love That Is Patient and Kind, R.C. Sproul

Kimberly has perhaps been speaking to her boyfriend’s sister, and can see straight through George. We’ve seen Ruth and Kimberly get up simultaneously to remove everyone’s soup bowls — these savvy young women are on the same intellectual level as each other. (Also, it’s easier to spot a toxic person when you’re not in a relationship with him.)

LABOR DAY AS MARKER OF DESCENT INTO DARKNESS

“The Summer People” is a short story by Shirley Jackson. As Alice Munro does in “Labor Day Dinner”, the labor day weekend marks a turning point for a couple, but in a very different way.

Jackson never lived to see old age, but she imagined it well. This is the story of two New Yorkers who spend summers at a country cottage. They decide one year to stay beyond Labor Day, but are disturbed to learn how unwelcome they are. Nobody helps them with supplies, nobody wants them around. The story feels like an allegory for how society feels when capitalism no longer has any use for us.

NARCISSISM ROUND UP

Have I managed to persuade you that Alice Munro has created a narcissist in George? She’s teaching us something really important in this story, yet in online analysis, I’m seeing too much blame heaped upon Roberta. Sure, there’s something in Roberta that’s broken. But we are given enough information to see that she wasn’t this broken when she came into the relationship. We’re told she’s hopeless. We’re told she’s useless for not following her dream of being an artist.

For goodness sake, don’t believe this surface narrative.

To get started, check out Dr Ramani’s video: “The DANGER of not “GETTING” narcissism“.

- George gives the silent treatment for reasons not explained to Roberta. This suggests he wants to punish her in a controlling way. See Dr Ramani’s “Narcissists and the Silent Treatment” on YouTube.

- Alice Munro gives us a single abusive incident but clearly signals this sort of thing goes on all the time because she also tells us Roberta has lost a lot of weight. Roberta doesn’t feel good about it. She now looks at her own reflection and only sees how old and unattractive she is. Narcissists don’t appreciate what’s right there. They crave something different. Life must be an ever-changing kaleidoscope of new experiences.

- Are ‘flabby armpits’ even a thing? Sure, arms can be ‘flabby’. But an armpit by its nature cannot be flabby. It’s a pit. George is criticising something that cannot even be true. He’s telling her black is white. Power comes from seeing her believe it anyway. (Note that even if she were flabby all over, such criticism remains acceptable.) He’s also going out of his way to reference a part of her body which is especially private. Certain body parts just feel more crude and private than other parts. We all know which ones. To mention someone’s pit or nostril or pores is a personal invasion.

- George also controls what she wears. “Why some narcissists feel the need to control everything“. When readers are told that Roberta spends a lot of time sitting around doing nothing, whose filter are we seeing that through? Could it be possible that any sitting around on Roberta’s part is considered unacceptable by this highly controlling individual? (Anyone who has done the whole grow your own food homesteading thing should see right away that Roberta has not been sitting around.)

- Roberta is in danger of turning to alcohol. Last night she got drunk, and she’s getting drunk again this evening.

- All the way to Valerie’s the pair are in a stand-off, but as soon as they arrive, George switches gear. Many if not most narcissists wear one mask in public, another at home. George would never let Valerie hear him insult Roberta about her weight or clothing or laziness. (Impulsive types of narcissists will behave badly both in private and in public.)

- Pretending with outsiders that you’re the good guy and everything’s fine is a lesser-recognised form of gaslighting. (“Everyone else thinks my partner is fine — so what’s wrong with me?”) See Dr Ramani’s “This is something you probably didn’t know was gaslighting“.

- Valerie is a mutual friend. We see no evidence that Roberta has kept in contact with friends of her own from her past. Oftentimes, narcissists will seek to isolate their partners/victims from a wider support network. See Dr Ramani’s “Dealing with the isolation of a narcissistic relationship“

- Valerie has the potential to be a good friend to Roberta but it’s possible George has chosen her as Roberta’s designated friend precisely because she’s not particularly interested in hearing the ins and outs of someone else’s relationship. See: “What to do when a narcissist turns people against you“.

- George slashing Roberta’s grass with a scythe is a performative thing to do. Powered tools to do this job existed in 1980. That aside, George is doing a favour to the designated outsider as a way of grooming Valerie. He wouldn’t want Valerie to consider him an unworthy person. A narcissist is low in self-worth underneath it all. (Might Valerie be a small-time self-serving narcissistic enabler? After all, she’s getting her grass cut.)

- George becomes the centre of attention at the dinner table. Valerie is good at drawing attention back away from him, but she doesn’t call him out.

- Narcissists tend to get bored easily. This may also explain why he preferred to scythe the weeds than sit around talking to Valerie. He’d be having to talk to people over dinner. He soon got bored of what others were saying, so chimed in with the Bible quote despite not understanding it. He just had to have something to contribute. People in a relationship with a narcissist often feel like they have to perform, lest they bore the narcissist. Valerie is a natural entertainer (because of her eccentricity) so we may not be seeing George at his bored worst in this scenario. But we are told that he can’t sit still. Narcissists have a restlessness about them. They are bored (and contemptuous) of everything, unless it’s something they’ve put forward to value.

- Munro shifts perspective constantly over the course of this story, showing that abusive relationships require the complicity of a community. This abusive relationship not Roberta’s issue alone. Were Munro to stick to Roberta’s limited point of view, that’s what readers may conclude. We’d only see how Roberta got her own self into this situation, how she blames herself for her previous failed marriage. But when focus shifts subtly to George we see how George is unable to accurately self reflect. He genuinely thinks Roberta’s daughters adore him. The younger Eva does. But neither of the post adolescent young women do. Angela’s diary entry shows us the difference in perceived reality and also marks the change in Roberta, who has not always been sad as she is now.

- Ruth is the character who evinces the arc of adoring adolescent girl to perspicacious young woman. It’s likely George went into teaching so he could wield power over young people. Narcissists tend to accumulate in other areas (banking, Hollywood, business) but can also be found hiding in the so called caring professions. A teacher is in a great position to surround himself with young, adoring adolescents who were previously providing his narcissistic supply.

- The night before the dinner at Valerie’s, George took Roberta out for dinner at a fancy lounge. Part of the difficulty in knowing you’re with a narcissistic abuser is, the relationship is not always bad. There will be good times in there somewhere, even if only at the beginning. By the time readers meet Roberta out the front of Valerie’s house, clutching a cold dessert, she is utterly discombobulated by this man. See: “A Mistake We All Make In Narcissistic Relationships“. After a good night out, hope kicked in.

- George is critical of Roberta for failing to earn money. But how is he doing that himself? I suspect the couple is living off savings. We are not told. But I am suspicious. When Roberta came out of her marriage, surely assets were divided. If not divided equally, surely she came to this partnership with something? We know George has plunged his money into buying the house. What has Roberta done with hers?

- George is critical of how Roberta hasn’t pursued her dream of being a picturebook illustrator. He has spread out his hobby tools in the house they share. Yet all of his own (ridiculous-sounding) sculpting projects sit unfinished as well. This is somehow Roberta’s fault. Roberta has had several illustration contracts already, in her previous life, showing she is good at what she does. (Any illustrator reading this story will know how difficult it is to get any picturebook work at all, and will consider Roberta a proven success.) Note that the moment Roberta becomes a successful illustrator, George’s jealousy will kick in. Narcissists are jealous people, due to insecurity. Roberta cannot win in her relationship with this man.

- George doesn’t appreciate that in a homestead-type situation, housework and cooking is a full time job in its own right. Only his renovation work counts as work. Narcissistic people do not experience empathy for others. Note that this way of dismissing housework speaks to a gendered cultural imbalance which happens to benefit male narcissists at the level of the home. This story hails from the very early 1980s. By using the word ‘labor’ in the title, I feel Alice Munro was saying something about how second wave feminism had the unfortunate unintended consequence of ushering in a new era for (middle class) women who, for the first time, were now expected to contribute financially to a household as well as do the very real work of keeping house, which in a less enlightened era had at least been considered real labour by society. (Women from poor families had always experienced that double burden.) Notice how the story features an ‘on the deck’ scene at both houses, subtly reminding readers that a deck is a very real, solid, tangible contribution to a home. A deck is a form of ‘enduring labour’. Labour typically performed by men endures. In contrast, the labour performed by women is ephemeral. A woman’s labour does not endure. Clean things soon become dirty. Food gets eaten. Alice Munro chooses a raspberry bombe to symbolise the ephemerality of women’s labour. This dessert has been made ‘from scratch’, after picking raspberries from around the homestead. Roberta has expended the emotional labour of needing to transport it while cold and getting it back into the fridge before it is ruined. Peak ephemerality. And then it is eaten. The consumers say it was okay. It’s as if it never existed. Invisible labour. Unappreciated.

- Roberta realises over dinner that she can deal with George by what psychologists now call grey rocking. That means making yourself as uninteresting as a rock. Psychologists recommend it. See: “What does it mean to go “gray rock”? (Glossary of Narcissistic Relationships)” What makes her realise? I believe it’s something Ruth says. Ruth has recognised that George wears a mask. She can see he creates the image of a liberal but is actually quite conservative. Roberta knows intuitively that George wears a mask. He’s not so much ‘conservative’ as ‘abusive’. I don’t believe she’s got to the point where she would use the word ‘abusive’. But someone else has seen through George’s public persona, and this is hugely validating for Roberta.

- Another interpretation: Roberta has not consciously realised that she can use grey rocking as a strategy. Instead she may be experiencing dissociation and numbness. Grey rocking by contrast is a learned strategy which tends to happen before a relationship gets to this point. Now that Roberta is at this point in the abusive relationship, she’ll need someone else’s perspective to pull her out of it. Readers have seen that this person is unlikely to be Valerie. (But it may be Valerie’s daughter.)

- Dr Ramani has a phrase to describe how narcissists do that Jekyll and Hyde thing for people outside the family. She calls it “The Dinner Party Effect”. Dr Ramani also talks about how the car ride home is often a dangerous arena. The couple is now alone together. The abuser tends to drive, and has the power to terrify the passenger. (Margaret Atwood writes an abusive relationship in her first novel The Edible Woman, and a scene in which the narcissistic lawyer boyfriend terrorises his girlfriend by driving recklessly one night.) In this Alice Munro story, terror comes from an oncoming vehicle, but how else might we interpret this scene? Where does the terror come from, really?

- Back to the grey rocking. A narcissist responds to grey rocking by trying to “hoover” you back in. This couple are about to enter the next phase of this awful relationship. Roberta will pull back and George will lean back in. This is how she will pull him out of his gaslighty silent treatment episodes. See: “What happens when you go ‘gray rock’?“

- Narcissists are often said to be love bombers. See: “How do broke narcissists love bomb?” It doesn’t always look like spending a lot of money on someone. This wouldn’t have worked on someone like Roberta. She craves a simple life. George would have worked out that how Roberta works. She’s drawn to fun, energetic guys. George is intense.

- George’s MO with Roberta is a bit different. He has built this jokey persona, honed in the classroom, whereby he dishes out insults and you’re not supposed to take him seriously. He seduces with an imitation of fun and good humour. In effect, Roberta won’t have been able to pinpoint the exact moment his insults changed from jokey guy to genuine abuse. She’s like a frog in a pot. This explains why she can’t see a dangerous dynamic while she’s in it.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Check out “Mastiff” by Joyce Carol Oates. Both stories explore themes around self-knowledge and relational identities. (Find Mastiff in the July 1, 2013 edition of The New Yorker.)

OTHER STORIES IN THE MOONS OF JUPITER (1982)

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings I: The Connection“

- “Chaddeleys and Flemings II: The Stone in the Field“

- “Dulse” in the July 21, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Turkey Season” in the December 29, 1980 edition of The New Yorker

- “Accident“

- “Bardon Bus“

- “Prue” in the March 30, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Labor Day Dinner” in the September 28, 1981 edition of The New Yorker

- “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd“

- “Hard-Luck Stories“

- “Visitors“

- “Moons of Jupiter” in the May 22, 1978 edition of The New Yorker