“Kiss Me Again, Stranger” is a short story by Daphne du Maurier, included in the 1952 Apple Tree collection (later published as The Birds and Other Stories).

WHAT HAPPENS IN “KISS ME AGAIN, STRANGER?”

A happy-go-lucky young working-class man with basic needs and a routine life is the first person narrator of this post-WW2 era story, set in and around London. He boards with an older married couple whose own children have moved out. By his own account, he likes these people he boards with, he likes his mother who lives in a town nearby, and he likes his boss at the garage where he works as a mechanic, doing a job he has enjoyed since boyhood.

One night he decides to go see a picture at the theatre rather than intrude upon a family dinner. He’s never had a girlfriend before, but now feels insta-attraction for the red-headed girl taking tickets. He’s desperate to engage her in conversation. Her replies are seductively sardonic. A mixture of shyness and sass, she doesn’t really care about her job. She’s your early 1950s version of an emo chick with a witchy vibe, since red hair indicates witchcraft, right?

During the film, which is a bog-standard Western (these days we forget how popular Westerns were among male audiences after the war), our narrator smells the girl’s perfume. She’s standing nearby. He is strongly affected by her aroma, which is like real flowers, not like the chemical perfumes other people wear. (With delayed decoding we might think she smells like actual flowers because she’s got this habit of lying around on things outside, regardless of weather.)

DU MAURIER’S SWITCHING EMPATHY TRICK

Now Daphne du Maurier does what they do best. As in “The Apple Tree” and “The Little Photographer“, du Maurier expertly manipulates reader empathy as our narrator follows this young woman home after work. He watches her get onto a bus, sits next to her, pays for her fare, drapes his arm around her… Not sure about you, but if this happened to me, I’d be startled and alarmed. Is this guy a stalker? Is he a full-on proper sexual predator? Have we been duped into thinking he likes everything and everyone and doesn’t want for much outside his quiet routine?

But I’m not there with them. I can’t feel their attraction. I must rely on the young woman’s response. She seems to like him, I guess? Wait… Is she trapping him? Is this a supernatural story? Is she a ghost? A ghost witch, luring this hapless young man with her natural scent to the edge of town where he will meet his end?

AN URBAN LEGEND VIBE

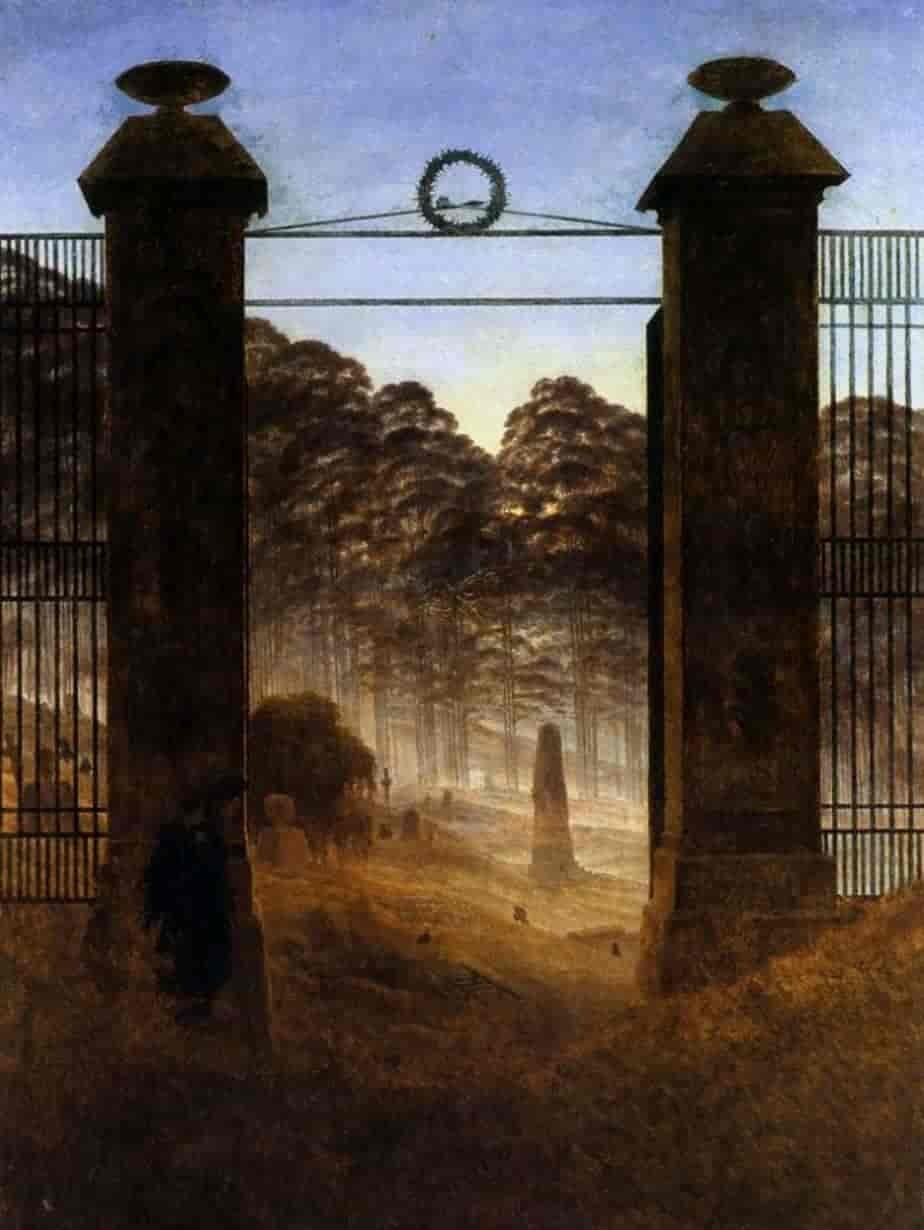

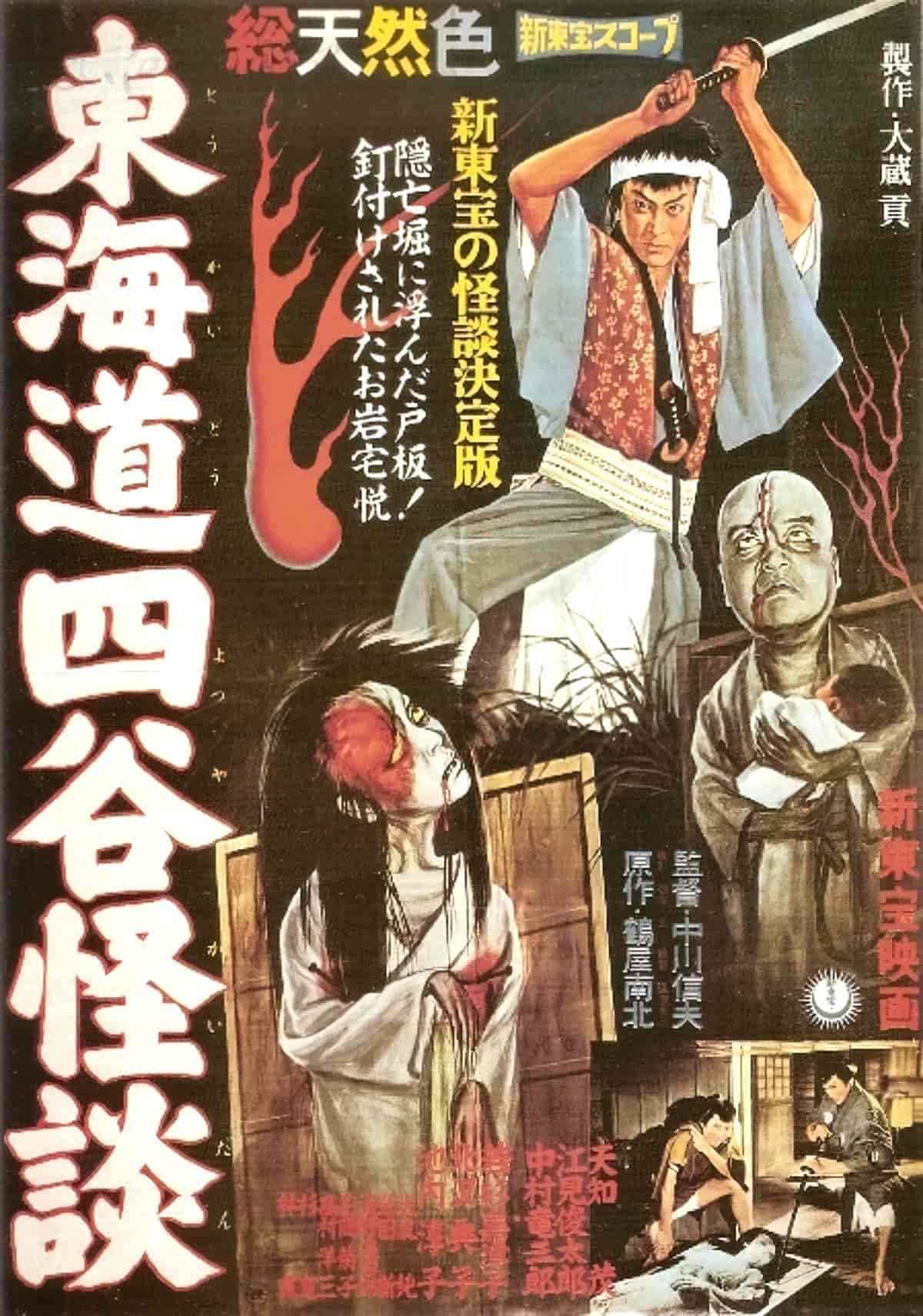

As the bus hurtles past one graveyard, contemporary readers may recall that category of hitch-hiker urban legend in which a ghost hitches a ride then asks to be dropped off at a graveyard.

Is this why my empathy switched?

IS THIS STORY SUPERNATURAL?

I’m wondering if she’s human. Also, this young woman doesn’t seem scared of our first person narrator. We’re getting the story through his eyes, so I’m still a little suspicious. But then they pass a graveyard and she says this isn’t the last graveyard they’ll be seeing that night.

As Margaret Forster’s revelatory 1993 biography made clear, Du Maurier had been like that since childhood, always dreaming up other possibilities, never certain that people, or even time, were as stable as they seemed. She certainly wasn’t. From a very young age she was what she called a “half-breed”, female on the outside “with a boy’s mind and a boy’s heart”.

As a child, this didn’t pose problems, especially in a family of actors. She dressed in shorts and ties and spent most of her time pretending to be her alter ego, Eric Avon, the splendid, shining captain of cricket at Rugby. But as she reached adulthood, this boy self “was locked in a box”. Sometimes, when she was alone, she opened it up “and let the phantom, who was neither boy or girl but disembodied spirit, dance in the evening when there was no one to see”.

Sex, jealousy and gender: Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca 80 years on, Olivia Laing

By the way, Du Maurier’s transgender or gender fluid identity may have contributed to her ability to slide seamlessly between characters, flipping reader empathy on a dime. She herself wore a page boy hairstyle (like the emo chick) and also described herself in letters to female lovers as a boy. Du Maurier refused to identify themself as lesbian (because if you don’t identify as ‘woman’ it’s harder to identify with a label made for women). Reading “Kiss Me Again, Stranger”, I get a strong sense of an author inhabiting both young man and young woman at once.

1950S MISOGYNY

The post war setting is intricately tied to du Maurier’s gender flips, fluidity and transgression.

Women’s lives in the WW2 era have been described as a parabola. I’m careful to note, working class women have always worked outside the home. (There’s a persistent myth that women only recently entered the paid workforce, which suits those arguing that childcare should be done by women in the home.)

After the wars of the 20th century, women were suddenly seen in the workforce. As soon as soldiers returned, men wanted ‘their’ jobs back.

This is an American statistic, but even after WW2 (in 1948), one in five married mothers remained in the paid workforce. (That’s only the married women.) By 1975, nearly half of married mothers of toddlers were in paid work.

Women in paid work was good for capitalism, good for women’s autonomy. Despite this, married women were culturally expected to return to casual, insecure, poorly paid work and to retreat back into the home. The jobs women entered during wartime were never ‘women’s jobs’. They always ‘belonged to’ the men, and women were thought to be donning the mask of manliness, and only because circumstances were dire.

Many women had enjoyed the freedom afforded by paid work. Those whose gender identity wasn’t particularly sticky, or binary, or cisgender, would have been particularly affected by the gender expansive possibilities experienced for the first time during the war.

Back to du Maurier’s story. The young man and the young woman get to the end of the bus line and the young man has admitted to his impromptu date that he doesn’t have enough money to get back, let alone go anywhere nice. This honesty is endearing.

They visit a coffee shop. If you’re sick and tired of misogynistic young men talking slap about women, this sequence will annoy you. It’s disappointing how toxic forms of masculine banter has failed to die in the 70 years since this story was published. (Catharsis is coming.) We don’t know it yet, but emo chick was as perturbed by the airforce soldiers’ banter as readers hopefully are.

LET’S HANG OUT AT THE GRAVEYARD

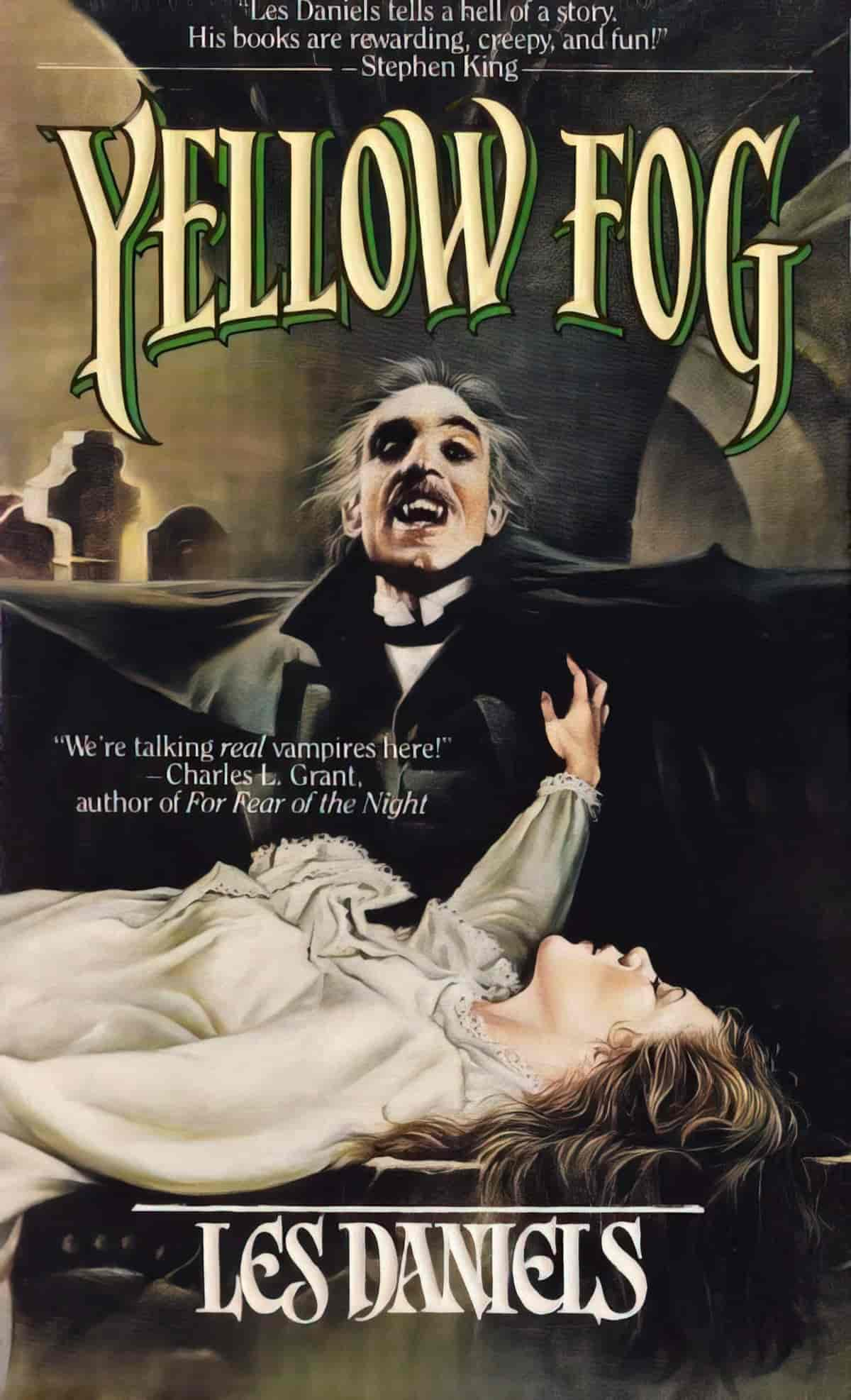

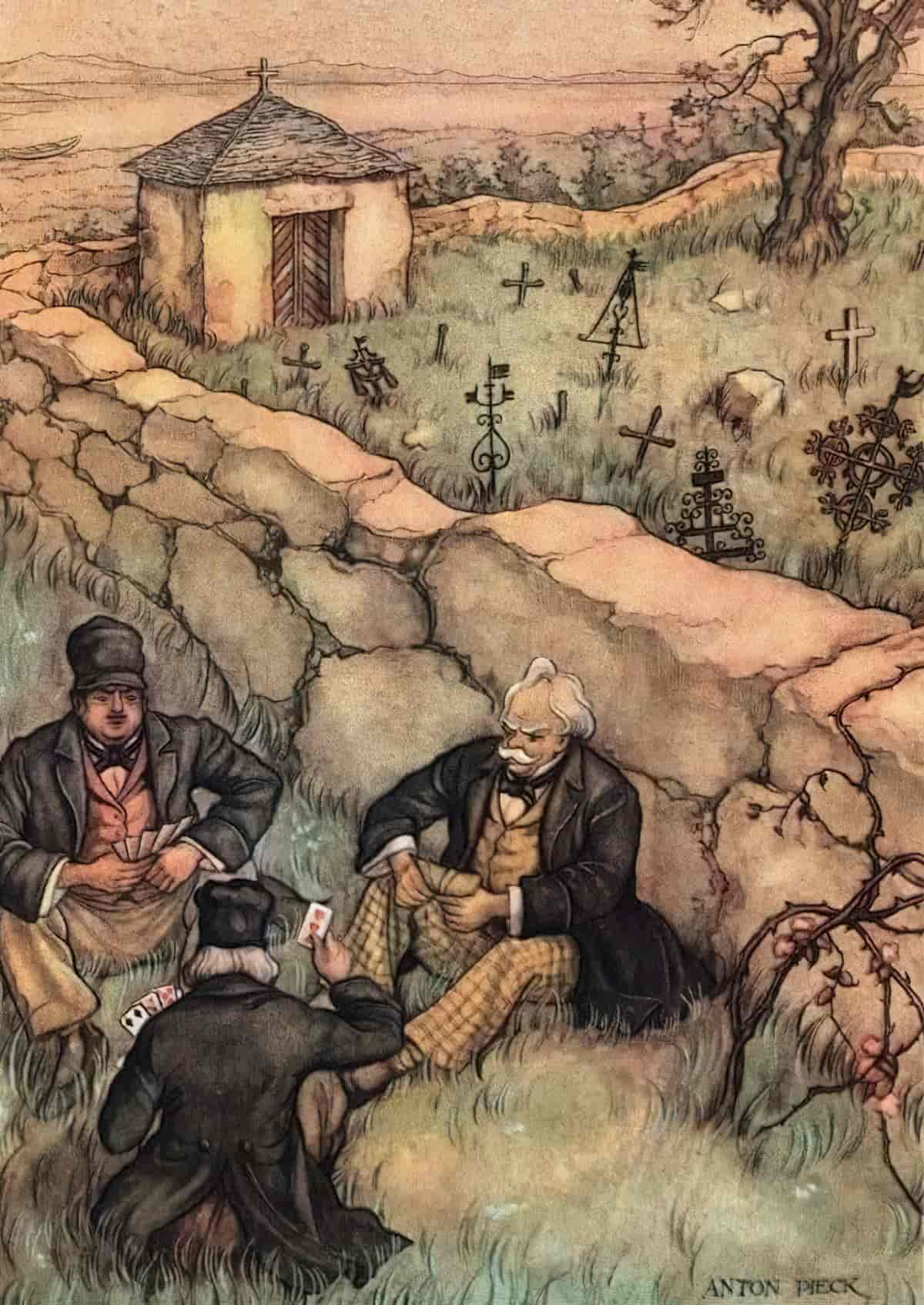

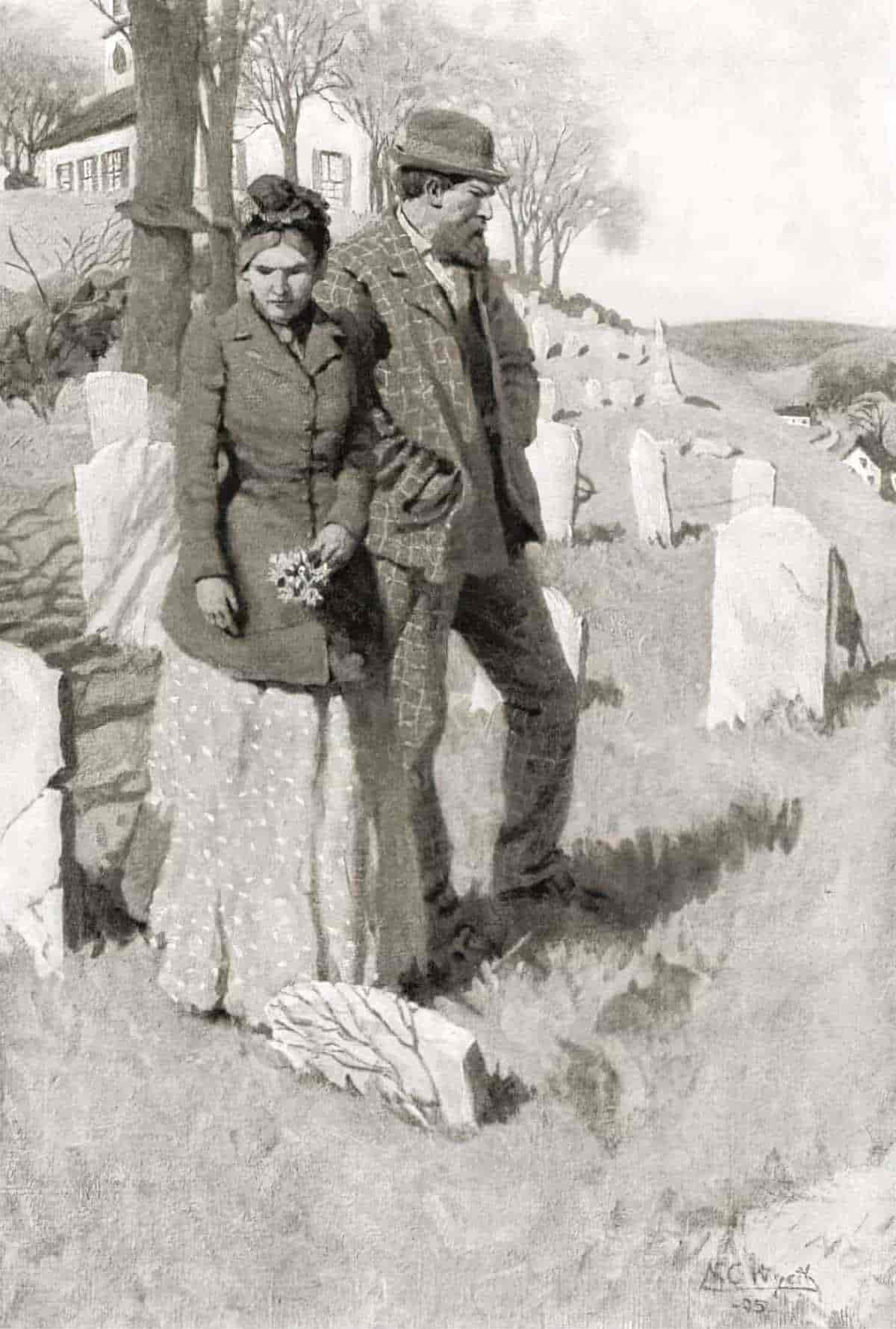

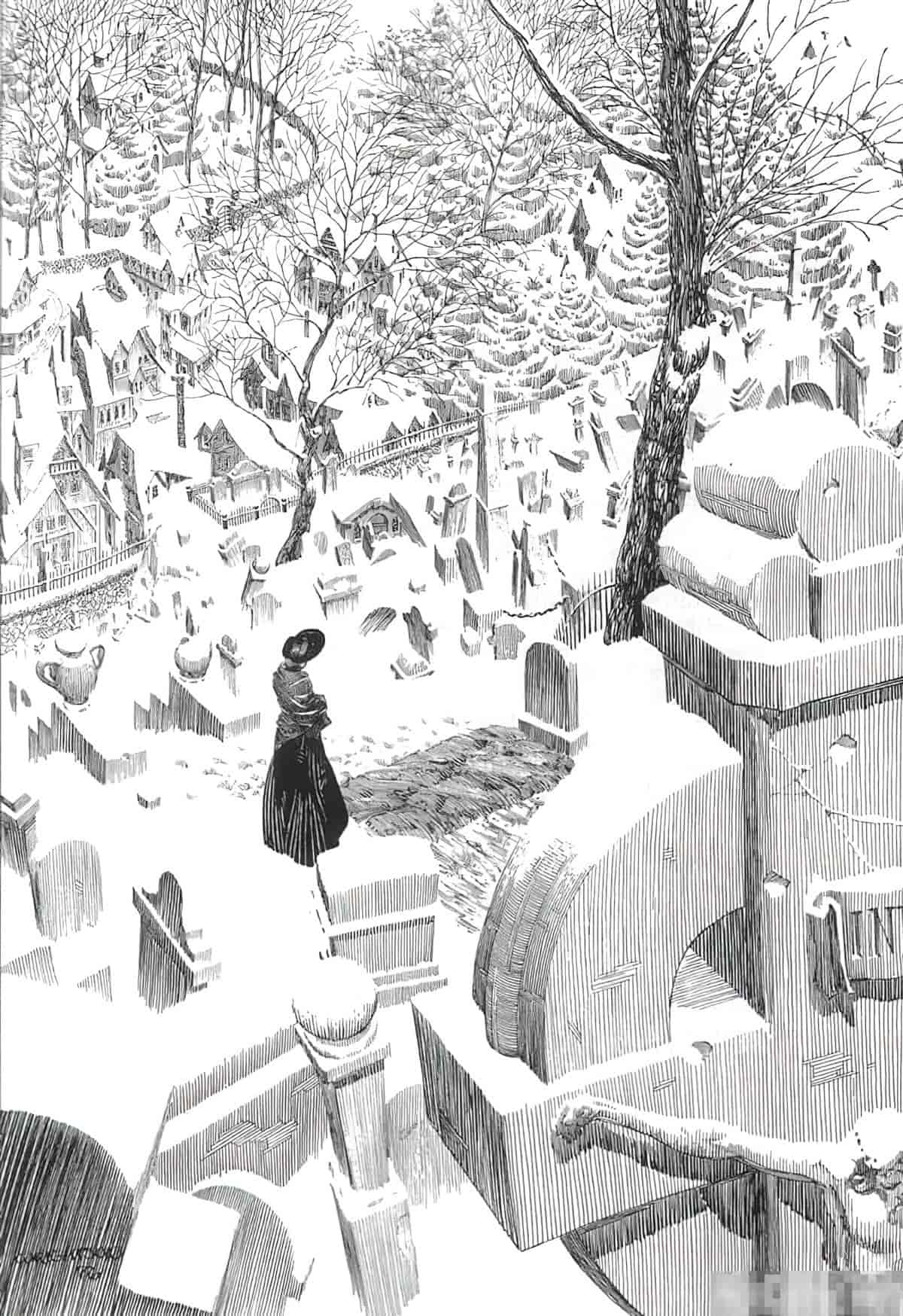

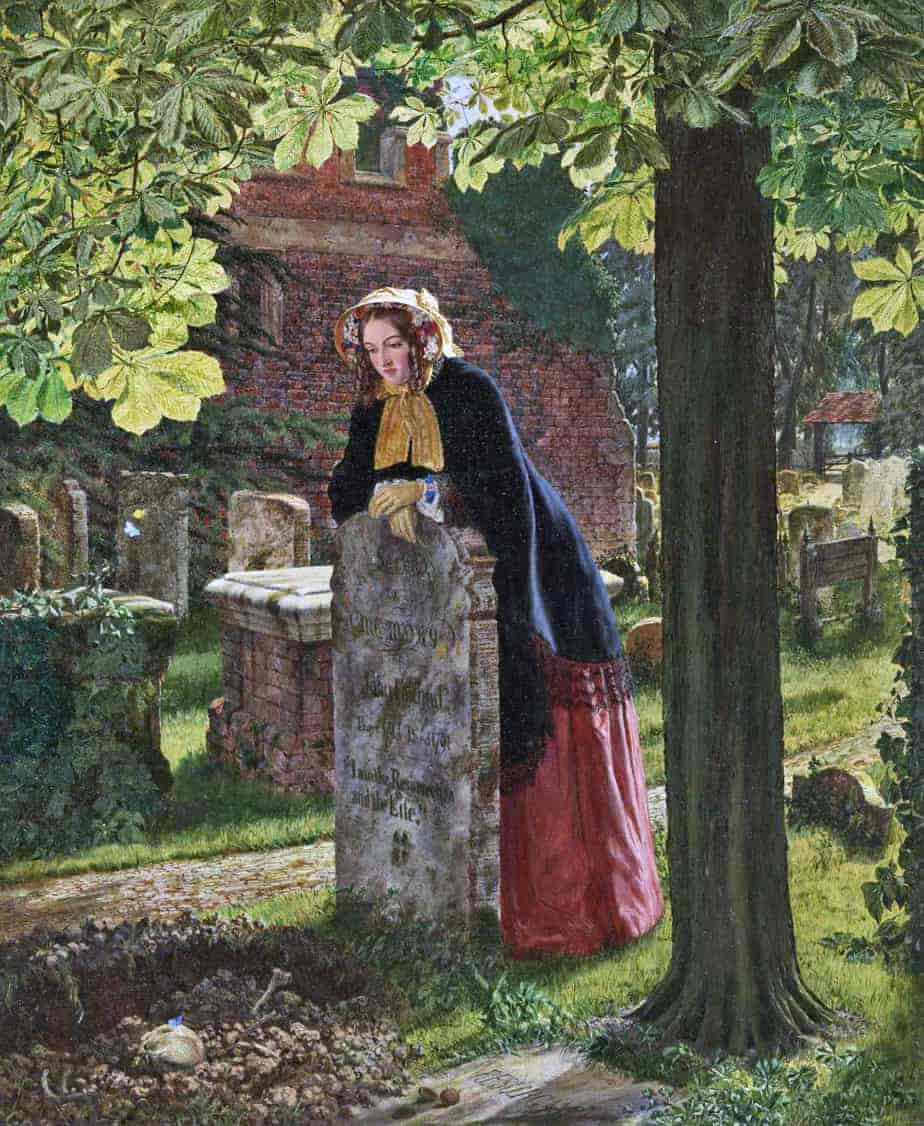

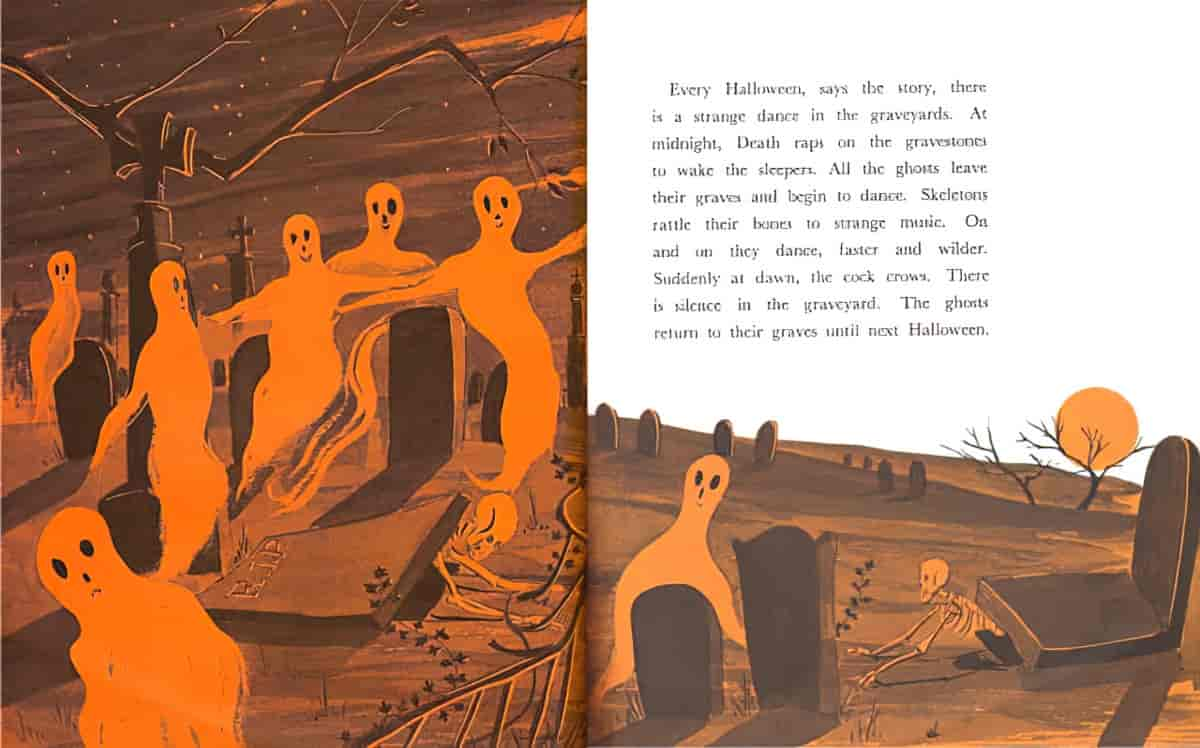

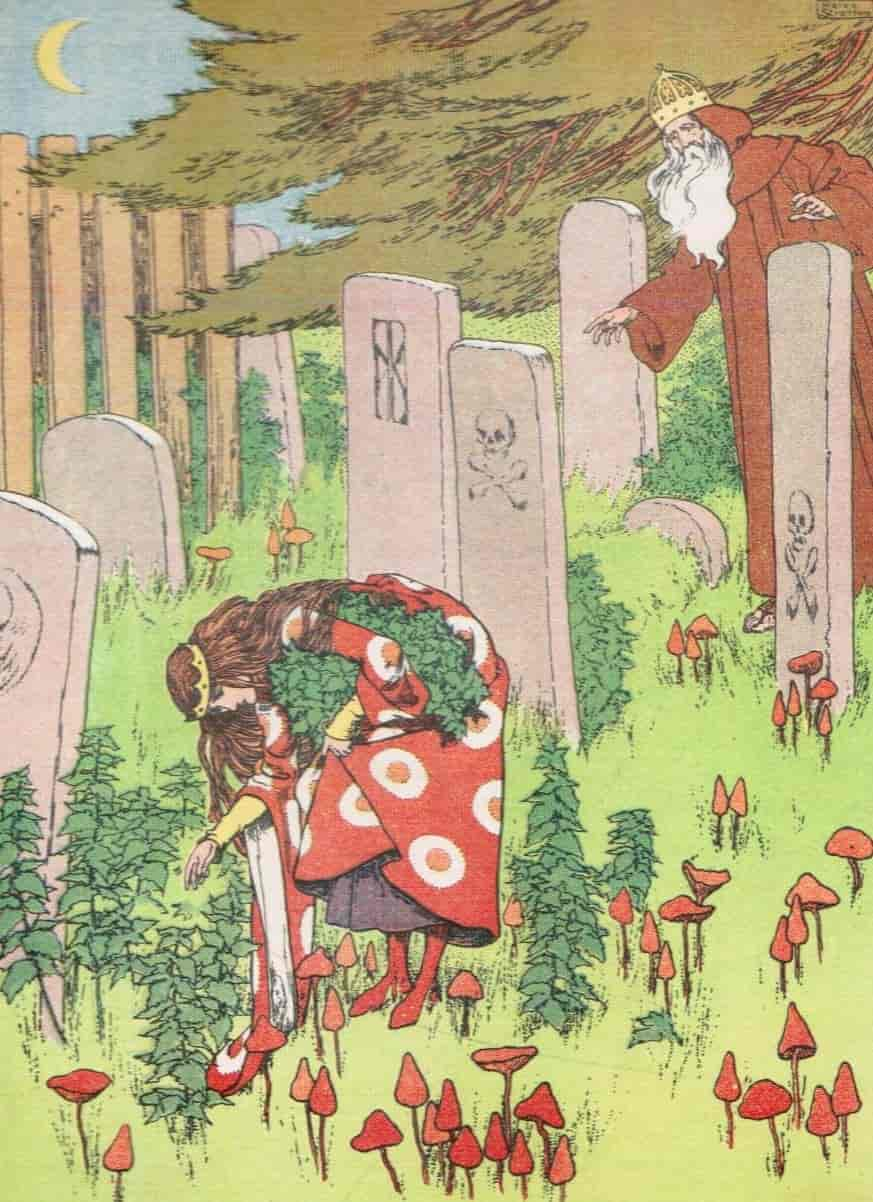

Emo chick leads our narrator to a fenced-off, lamp-lit graveyard, where many of the tombstones are large and flat. She lies down on one of them. Is she a vampire? A succubus? Various supernatural creatures come to mind.

Our boy wants none of this. It’s cold, it’s raining, he has no money to get back home so he’s got a very long walk ahead of him tonight. Sister wants to have a date in the graveyard? But she’s pretty. Very pretty. He’s been taught chivalry. A gentleman stays.

The narrator is a fast mover. He’s never had a girlfriend before but here he is plotting their future together. He doesn’t even know her first name. He’s chatting on, she’s not responding. He seems spellbound by someone otherworldly.

Emo chick reveals a bit of her backstory. Her parents were killed during the war. Her family home was bombed. She blames the British airforce. Our boy corrects her. Blame the Germans. She tells him airforce men are all the same.

After checking he’s not an airforce boy, Emo chick instructs him to go. Don’t look back.

The next day, the narrator spends savings and then some on an expensive heart-shaped brooch, the colour of her eyes. But when he returns to the picture theatre to give it to her, she’s been replaced by a different girl. The new girl tells him funny business has happened. Last night’s girl has been taken in by police, accused of serial murder of local airforce men. Hasn’t he heard about it? Another was killed last night.

The narrator is left to contemplate the brooch, discomposed as we are.

“KISS ME AGAIN, STRANGER”: A FINE EXAMPLE OF A LIMINAL STORY

The Gothic has become impossible to define but I’ll call it: We’re reading a Gothic story. The graveyard is a liminal space, connecting the living to the dead. I, for one, have been wondering if emo chick is actually a ghost.

Du Maurier’s graveyard is a doubly liminal space because it’s situated at the edge of London, inhabiting the geography between civilisation and nature, not just the space between living and dead. (Because the narrator comes so close to death, the story straddles life and death without being supernatural.)

Indeed, “Kiss Me Again, Stranger” is about as close as a story gets to supernatural content without actually being supernatural. Of course, we’re meant to wonder if emo chick is a ghost because of all the Gothic tropes. Ghosts come and go, unpredictably emerging from behind the veil. Perhaps she’s not talkative because she’s… no longer there? Du Maurier’s got me thinking back to the bus, to the picture theatre — did this young woman have any interaction with other characters, or just him?

HOW TO TELL IF LIMINALITY APPLIES TO A STORY

Not every story is ‘liminal’. Three criteria: Liminal situations are fluid, malleable and multi-layered.

HIERARCHIES REVERSE

Social hierarchies can reverse, as in a carnivalesque story. Here, it’s not a social hierarchy that reverses, but a gendered hierarchy. Via dialect in dialogue, du Maurier depicts both characters as working class. Gender rules and expectations are widely understood and widely enforced but du Maurier is performing several inversions here. Regardless of what actually happens between lovers in private, in post WW2 England, it was expected that men do the pursuing, women do the waiting. Sure enough, that’s how the story begins. The young man pursues the young woman in the most literal of ways. But look at the title. By the time she’s asking him to kiss her, gender roles have flipped. For the era, she’s being sexually aggressive. As contemporary readers it’s difficult to image the taboo on women kissing men, or asking to kiss a man she has just met. Twentieth century French feminist and existentialist Simone de Beauvoir wrote this:

The little girl […] is allowed to cling to her mother’s skirts, […] she wears sweet little dresses, her tears and caprices are viewed indulgently, her hair is done up carefully, older people are amused at her expressions and coquetries […] the little boy, in contrast, will be denied even coquetry; his efforts at enticement, his play-acting, are irritating. He is told that “a man doesn’t ask to be kissed… A man doesn’t cry.” He is urged to be “a little man”.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 1989 (published originally in 1949)

This is nothing. The ending shows the extent of her ‘aggression’ (probably revenge). In this story, gender roles are fluid and malleable.

THE UNHEIMLICH FEELS

Something feels weird here, but it’s never seen, never named and never known. People wouldn’t believe you if you told them about it. This is the epitome of ‘liminal’. At the end of the story, after the narrator learns he’d have been murdered had he been an airforce soldier, he refuses to tell anyone about it. The newspaper asks him to come forward to help police build a case, but as the story ends, there’s no indication he’ll do this. The experience was so close to being supernatural, the attraction felt so strongly by himself yet so difficult to explain, he can’t possibly tell the police about it and have them believe him.

MORAL DILEMMA

If you’re in a liminal space you’re facing a moral dilemma. Your circumstance allows you to question social constructs. Which world do you want to be a part of? Once you’re in that liminal space you can choose to progress or retract, to take hold of freedom or remain in a state of metaphorical slavery. Emo chick tells the narrator to leave her alone and not look back. (Check out the Don’t Look Back entry at TV Tropes.) This requires him going against his instinct to look after her forever. Good Men (TM) of this era are taught to look after women and children. That’s his moral dilemma. Readers can extrapolate that if he hadn’t done as she’d asked — if he’d crossed her personal boundaries — she’d have killed him as well as (or instead of) the misogynistic airforce soldiers.

REVELATION

In stories, the liminal part is where the main character has an Anagnorisis (revelation), or makes a moral decision. The narrator of “Kiss Me Again, Stranger” faces two moral decisions. Leave a girl alone in a graveyard or no? Go to the police with information or no? The first dilemma prefigures the second. What does he learn, if anything? If he’s able to put two and two together — and I’m not sure he can — he’ll understand a little more about how other men behave towards beautiful young women, even though he, himself, is one of the Good Guys.

GRAVEYARD SETTINGS IN FICTION

Du Maurier utilises stock gothic components: Fog, graveyard, night, a young seductive woman who may be a ghost or a witch. The author incorporates contemporary replacements to help 1950s readers feel this story could happen to them, e.g. replacing moonlight with a nearby streetlamp, and a padlocked iron door with an easily penetrable graveyard fence.

Time works differently in graveyards

Du Maurier’s goth chick points out that some graveyards are full of flat slabs. These replaced the hand-carved headstone popular in earlier eras. By the second half of the 20th century, stonemasonry is a dying art. Emo chick pointing this out evinces post World War anxieties regarding the rate of technological change.

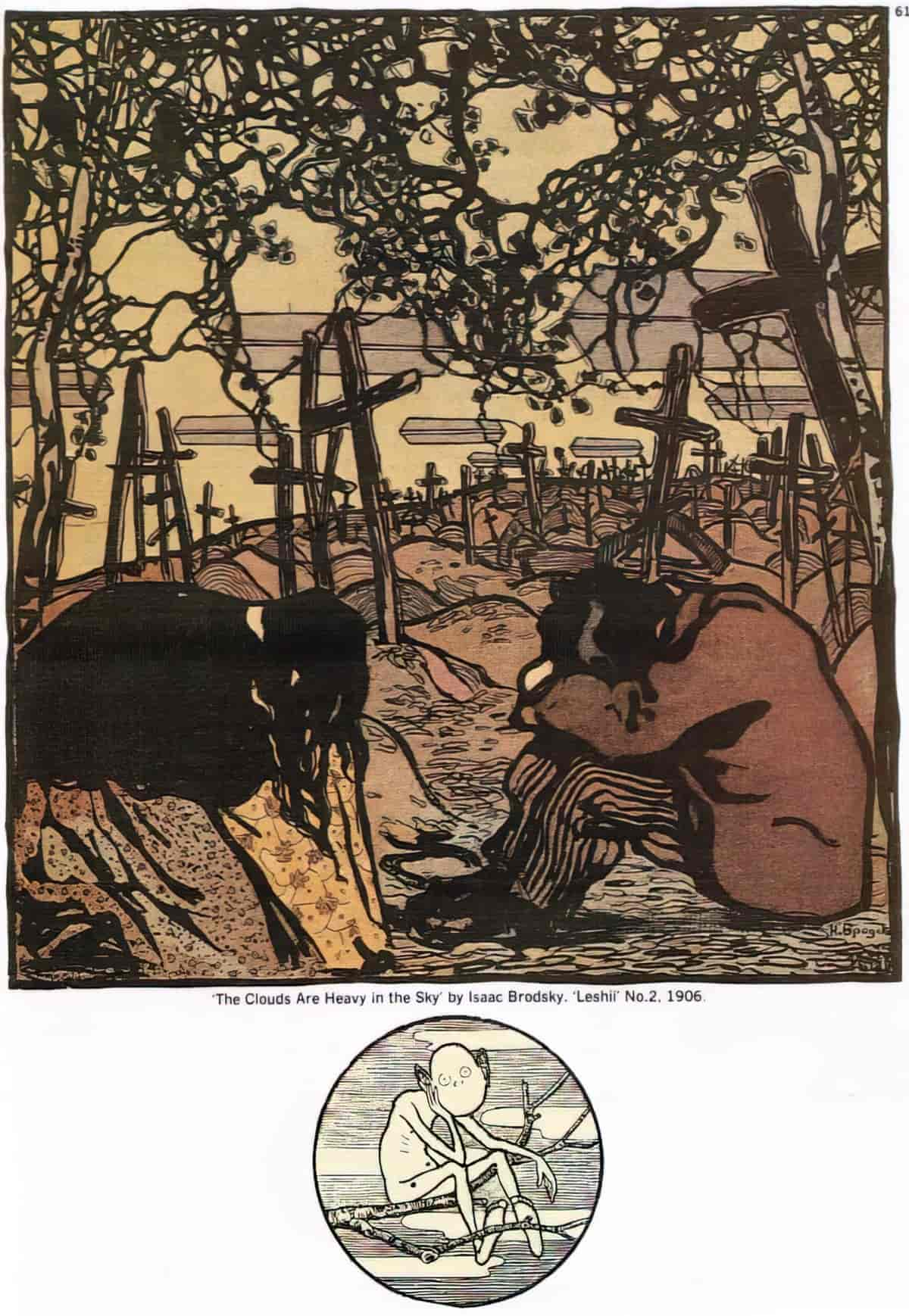

GRAVEYARDS IN ART AND ILLUSTRATION

The Dark Swamp: Horror Stories Episode 701: NEVER Play In An Abandoned Graveyard! | The Dark Swamp Ep 701

Making Space for the Dead: Catacombs, Cemeteries, and the Reimagining of Paris, 1780-1830

In Making Space for the Dead: Catacombs, Cemeteries, and the Reimagining of Paris, 1780-1830 (Cornell University Press, 2019), Dr. Erin-Marie Legacey, Assistant Professor of History at Texas Tech University, explores the transformation of burial practices in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Public health concerns under the Old Regime prompted reforms in how the French buried their dead, with millions of bones carted away from church graveyards to the deserted mining tunnels underneath the city. After the Revolution, the Catacombs, as well as newly established cemeteries such as Père Lachaise, became more than simply places for the disposal of the deceased. Amidst the turmoil and upheaval wrought by the Revolution, these burial sites became public spaces for Parisians to, as Dr. Legacey writes, “assert and assess their radical break with the past, to reconsider a new set of moeurs in the wake of that break, to reconnect with their fellow Parisians, both alive and dead, and to reimagine their past and its relationship to the present.”

interview at New Books Network