Critics who treat adult as a term of approval, instead of merely a descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown up because it is grown up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these are the marks of childhood and adolescence […] The modern view seems to me to involve a false conception of growth … surely arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new things?

C.S. Lewis, 1966

One of the oddest things we do to children is to confront them with someone else who is also eight, or ten, or seven, and insist that they be friends … What concerns me is the misconception that people are fossilised at any particular point in a lifetime. We are none of us ‘the young’ or ‘the middle-aged’ or ‘the old’. We are all of those things. To allow children to think otherwise is to encourage a disability — a disability both of awareness and communication.

Penelope Lively

‘Notions of the “child”, “childhood” and “children’s literature” are contingent, not essentialist; embodying the social construction of a particular historical context; they are useful fictions intended to redress reality as much as to reflect ideology of Romantic literature and criticism. These ideas have been applied to eighteenth-century children’s authors such as Maria Edgworth. The child constructed by Romantic ideology recurs as Wordsworth’s ‘child of nature’ in such figures as Kipling’s Mowgli and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Dickon in The Secret Garden and, as one critic points out, ‘many children’s books that feature children obviously wiser than the adults they must deal with — like F. Anstey’s Vice Versa or E. Nesbit’s Story of the Amulet — would have been unthinkable without the Romantic revaluation of childhood’.

History and Culture in Understanding Children’s Literature edited by Peter Hunt

What exactly is a child?

The labels themselves have the result of setting boundaries: child, adolescent, teenager, young adult.

See also: Episode 137 of the Then Again Podcast: Childhood in Iron Age Europe with Megan Kimmelshue. Marie discusses growing up in Iron Age Europe (about 800 BC – 43 AD) with Doctoral Candidate Megan Kimmelshoe of Bangor University in Wales. What can we know about childhood during this period based on archeological findings? How did children play? What toys did they have? How were they educated? Learn all of this and more in today’s episode!

Historically, during the Renaissance (1400s onwards), society’s thinking changed hugely, starting with religion, into ideas of government. Art changed, music changed. All of these things happened over a couple of centuries.

The Renaissance change in attitude towards the child is typified by this painted icon of Madonna and Child (1228), and conveys the idea that the child is simply a smaller version of the adult.

+(fl.+1228-1236).jpg)

The baby Jesus is being held by his mother, in terms of the proportion of the arms/legs/head is an adult figure. [Might this simply be a bad painter, or reflecting the idea that the baby Jesus was never a normal baby? However, I get the idea.]

This had changed by the mid-18th century.

Adults were beginning to think of themselves as fundamentally different kinds of creatures from those who were their children. The child was no longer thought of as a little adult. Childhood was conceived as a special and vulnerable stage; adult hood was defined in reversed terms.

Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man, 1993

The following passage from Aesthetic Approaches to Children’s Literature: An Introduction, by Maria Nikolajeva, is an interesting glimpse into how just 100-200 years ago, children were seen as pure and untouchable. The idea that any adult could be sexually attracted to a child and cause them harm never crossed anyone’s mind in such a culture:

Two recent biographies of Lewis Carroll have portrayed him in two radically different manners, both strongly deviant from the standard view proposed in a biography written in 1899 by his nephew. One of these paints Carroll as a pedophile, based on his ostensibly pathological interest for little girls. The other biography, going back to Carroll’s unpublished diaries, points out that the “little girls” in question were in fact around twenty-five years old, and that they used to visit Carroll unchaperoned, which in the eyes of his contemporaries was highly immoral. Apparently, the myth of the author’s interest for “little girls” was deliberately created by his family to hide what they regarded as inappropriate, while children were considered pure and innocent and therefore suitable as a cover. For us today, pedophilia is certainly a worse offence. This is a good example of how facts about an author can be interpreted differently. Our understanding of Alice in Wonderland can be affected by our understanding of the author’s views on children.

Maria Nikolajeva

A different but related idea

I think the way we’ve constructed adulthood against and alongside our construction of childhood is bad for adults. It’s bad for children, too, but it’s also bad for adults. In the same way that sexism is bad for women and men, so too is our adoration of The Child bad for the child and the grownup.

The Moving Castle

What is a naughty child?

When you see a child throwing a tantrum in the supermarket and the carer smacks the child – should you use violence on a child? Is the child being naughty or is the child simply doing what the adult doesn’t want? Does the child have the capacity to make the moral judgement between good and evil? Before the Renaissance, it was assumed. Humans were thought to be inherently evil, because we were descended from the evil Adam and Eve. Therefore every child ever since is sinful and accepts responsibility just like everybody else. John Locke and others presented the idea that the child became not the adult but the baby Jesus, essentially innocent and pure, corrupted by the world. This is a huge change in thinking.

Should children be treated differently?

A couple of the gospels from the Christian Bible: Mark 10:14, repeated at Luke 18:16. A group of children were trying to get to Jesus. They were being held back, but said that the children are special and let them come to me. The bible says unless we humble ourselves like little children we’ll never get into heaven. This was recognition that children could not and should not be treated as adults, but it took the rest of the Western world another 1500 years or so to wake up to this idea, but wake up they did, in the Renaissance.

Schooling became a structured, organised social activity, not just something parents passed onto their children. Before the Renaissance, if your father was a weaver, you were a weaver. Schooling became a social construct between the 1700 and 1800s. It was originally provided by the church, in Britain and then copied in Australia. Eventually schooling was compulsory – in 1872 both in Britain and in Victoria here in Australia. That separated children as a social group. They were not just part of a family, but part of the group of ‘school children’.

Before this were labour laws prohibiting children from being employed, originally when they were 12, then 14. Even in the 1930s and 1940s, most people left school after about the age of 14 (what we would call Year 8) and go to work. Only a few would go on to specific qualifications to become professionals. Anne of Green Gables finished school at about year eight. Next year she’s back as the teacher, teaching the class. After a couple of years of doing that she goes off to university to become a teacher.

There were laws about when a person could marry, engage in sexual activity, when they could inherit and so on. These laws gradually started coming in to protect the child and childhood. The middle class came about after leisure came about. People had money to buy books, for example.

Teenagers, or the concept of ‘teenagehood’ came about much later, in the 1950s.

Huge social upheavals happened. Disposable income, compulsory schooling – all of those elements were leading to this point, and probably should have happened earlier, but the World Wars and Great Depression inserted turmoil. Gender roles were also important. Women were required in the workforce and therefore unable to look after the children as they were able to before.

All of a sudden there was a jump between the child to the 18 year old adult, fixed by warfare, because you were unable to fight before the age of 18. This gave birth to ‘the teenager’. Rock and Roll occurred because there was a group who couldn’t yet fight or do other adult things.

When do you pay full fare to the movies or on the plane? (When you fit into a seat rather than on someone’s knee.)

When can you leave school?

When can you work?

It’s blurred there, because there is an upper limit on hours for teenagers. When can you smoke, marry? Between 10 and 16 children can engage in sexual activity, as long as the two partners are both consenting and within two years of age. If you’re over 16 there are still some limits, if you’re over 18 open slather, with anyone. Anywhere between about 3 and 25 for certain inheritance laws. Is a 19 year old the same as a 13 year old? They’re both ‘teenagers’. The word ‘adolescent’ implies that there is growth but it is not yet there.

The Unborn Are Convenient To Advocate For

“The unborn” are a convenient group of people to advocate for. They never make demands of you; they are morally uncomplicated, unlike the incarcerated, addicted, or the chronically poor; they don’t resent your condescension or complain that you are not politically correct; unlike widows, they don’t ask you to question patriarchy; unlike orphans, they don’t need money, education, or childcare; unlike aliens, they don’t bring all that racial, cultural, and religious baggage that you dislike; they allow you to feel good about yourself without any work at creating or maintaining relationships; and when they are born, you can forget about them, because they cease to be unborn. You can love the unborn and advocate for them without substantially challenging your own wealth, power, or privilege, without re-imagining social structures, apologizing, or making reparations to anyone. They are, in short, the perfect people to love if you want to claim you love Jesus, but actually dislike people who breathe. Prisoners? Immigrants? The sick? The poor? Widows? Orphans? All the groups that are specifically mentioned in the Bible? They all get thrown under the bus for the unborn.”

Methodist Pastor David Barnhart

THE SYMBOLIC BINARY BETWEEN INNOCENT AND FALLEN

The born are ‘fallen’; only the unborn can be ‘innocent’.

Women are human, and as such can never be as innocent as the unborn. But innocence (as we see every time a police victim is described as “no angel” by the press) is a fundamentally inhumane category in politics, deriving from the most punitive interpretations of Christianity. According to this imaginary, non-innocence is the core characteristic of everything “fallen,” which is to say, everything that has ever lived. […]

Fetishizing newness and sentimentalizing helplessness, pro-lifers pit themselves ruthlessly against the overwhelming majority of human life-in-particular. In their minds, fetuses deserve every protection, while we actually existing human beings belong to a completely different species. We are on our own, self-responsible; fatally compromised, because enfleshed.

Sophie Lewis at The Nation

Child As Symbol Of The Future

When considering the symbolism of the child, pair with the elderly person, who represents the past. In popular imagination, we consider life as a circle, in which the very elderly return to a kind of childhood. Live long enough and we become transformed. We acquire a new simplicity. This idea comes from Cirlot, who thought that if you dreamed of a child, some great spiritual change would be about to take place under favourable circumstance.

Nietzsche deals with this idea in relation to the ‘three transformations’ in Thus Spake Zarathustra. Nietzsche wrote about the process of spiritual transformation. He believed there were three distinct phases of self-actualisation, represented by:

- The camel — the hump on its back represents your burdens, conquests and scars

- The lion — in this stage you want to be free and be lord of your own desert

- The child — you can’t be fully mature until you recapture the serious play which defined your youth.

The Imaginary Child is a concept to describe the way pro-natalists want every adult to procreate in order to save the nation. This concept is widely understood in places such as Romania, which is facing a decreased birth rate and widely publicised census. The concept of The Imaginary Child has real social consequences for those who choose not to have children, impacting heavily on the GRSM (gender, romantic and sexual minorities) community especially. Even when queer people do procreate, their queerness is blamed for falling fertility rates, and fear of the ‘Queer Apocalypse’.

Child As Angel

Enlightenment philosopher John Locke famously said that the child is a blank state (tabula rasa, “white paper”). Children gradually fill with knowledge on the road to adulthood.

Romantic poets and philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and William Wordsworth romanticised the tabula rasa child as a natural, pre-rational human. The Romantics thought that childhood is “the sleep of reason”.

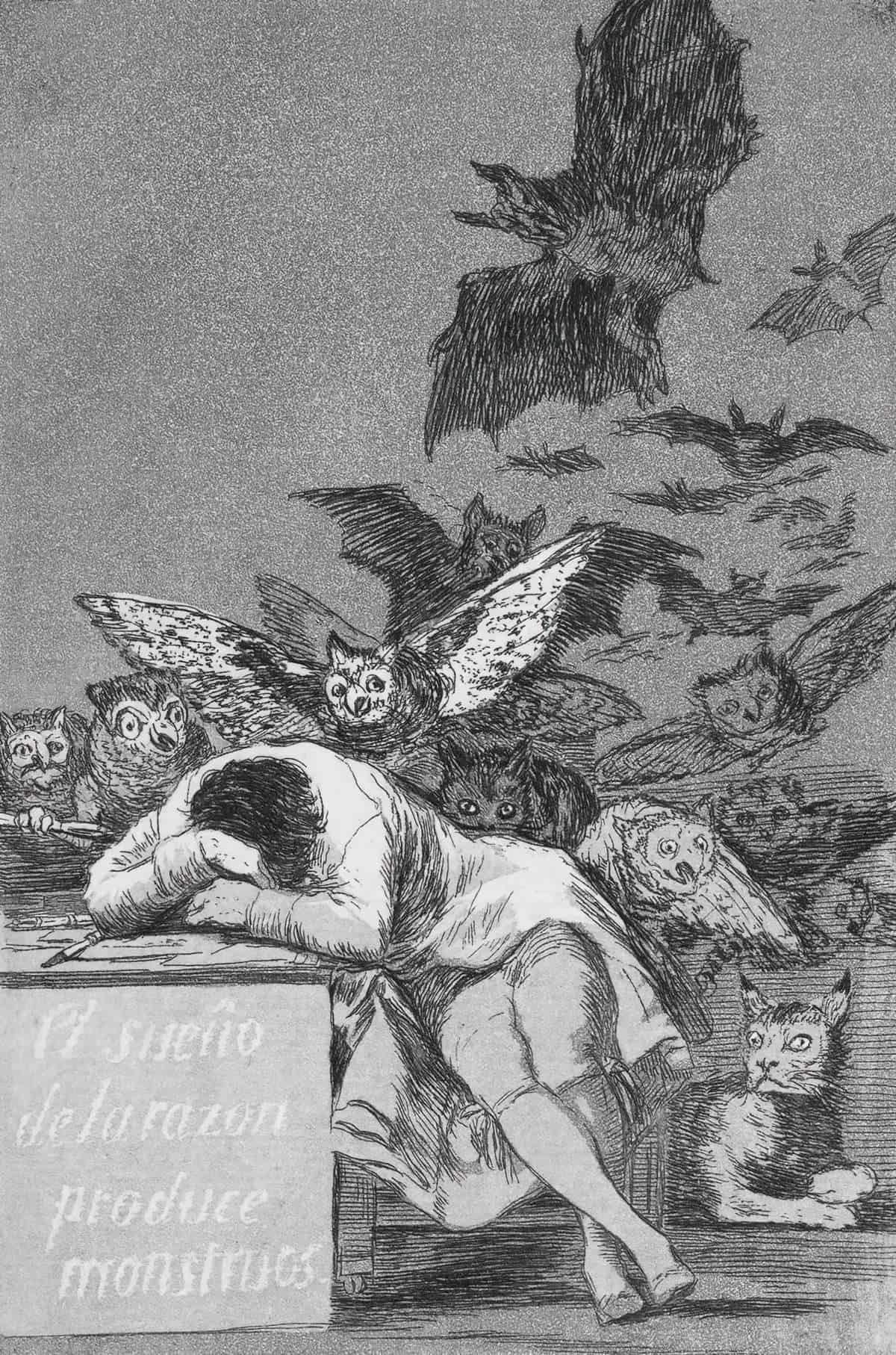

These are 18th and 19th century ideas, but continue to influence the present. The idea that children are blank slates can be unsettling as well as comforting. The Spanish painter Francisco Goya suggested in the title of a famous work: “the sleep of reason produces monsters“.

Children are an example of a symbolic paradox. We find them familiar but also weird. They live in our families but seem also to live on a separate plane. Our own children are like ourselves but sometimes disturbingly different. Marina Warner points out that these contradictions around the child come from the “concept that childhood and adult life are separate when they are inextricably intertwined”. I’m sure this has something to do with what Julia Kristeva said in her famous essay on Abjection. Humans have real trouble accepting things when categories don’t have firm boundaries.

This explains why childhood bogeyman infection the worlds of adults are so popular in horror stories. There’s been a resurgence in these bogeyman films in the 2010s.

Children aren’t as rational as adults but at the same time they are thought to have insight that is lost to adults.

Partly this is because children notice things which adults have long since learned to ignore.

Although adults can beat children at most cognitive tasks, new research shows that children’s limitations can sometimes be their strength.

In two studies, researchers found that adults were very good at remembering information they were told to focus on, and ignoring the rest. In contrast, 4- to 5-year-olds tended to pay attention to all the information that was presented to them – even when they were told to focus on one particular item. That helped children to notice things that adults didn’t catch because of the grownups’ selective attention.

Children notice what adults miss, study finds: While adults focus their attention, children see everything in Medical News Today

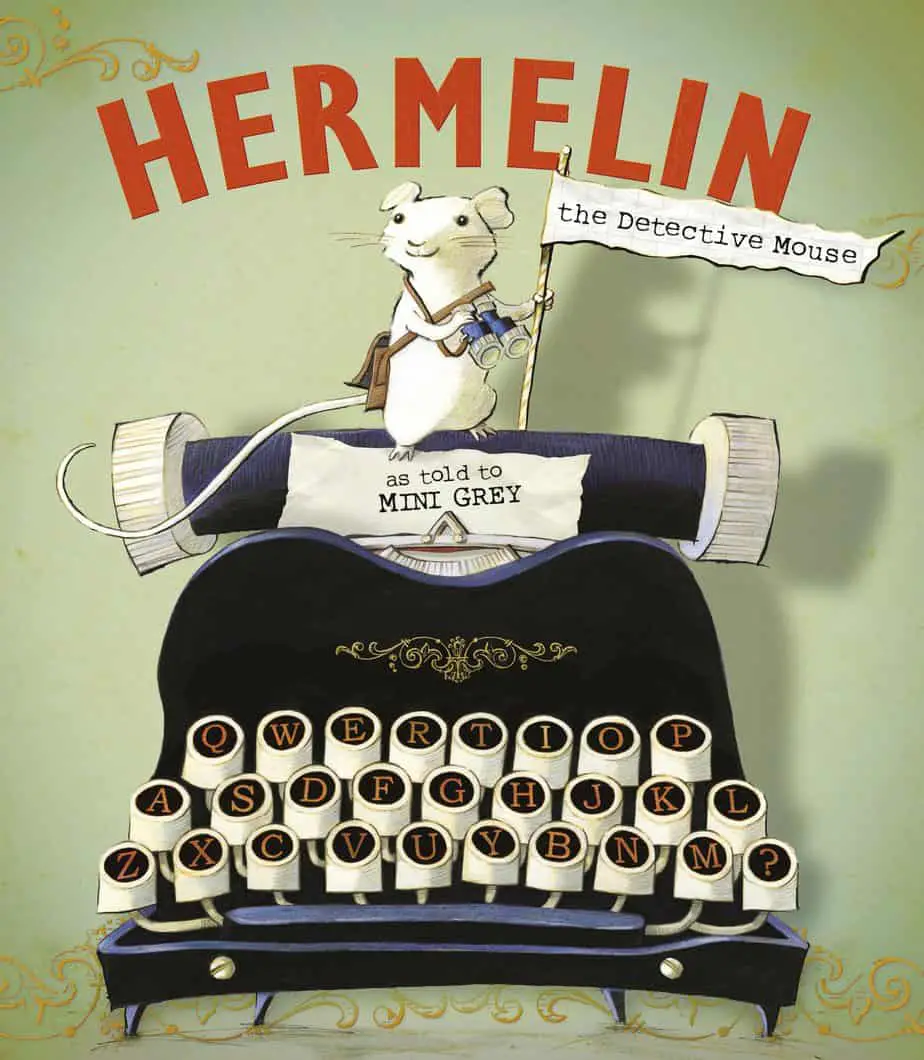

The superpower of noticing is heavily utilised in children’s literature. One of the few advantages children have over adults: Noticing. Children (or child stand-ins such as mice) will often solve a mystery simply by noticing what adults have failed to see right there before them.

Their observable, active fantasy life, and their fluid make-believe play seem to give [children] access to a world of wisdom.

Marina Warner

Hermelin is a noticer. He is also a finder. The occupants of Offley Street are delighted when their missing items are found, but not so happy to learn that their brilliant detective is a mouse!

What will happen to Hermelin? Will his talents go unrewarded?

In Margaret Mahy’s young adult novel The Tricksters, the main character’s mother (Naomi) is reading a book by the beach, even as her own daughter is being led by a creepy newcomer who won’t let go of her hand. The wish to enjoy some solitude on a big family holiday is relatable to any parent, and obliviousness works well as a plot device: to plunge the young adult main character headlong into danger, where she’ll have to find her own way out again.

“Pass on by!!” Naomi shouted as they hesitated. “Don’t give me any news or ask me any questions or tell me anything.”

The Tricksters by Margaret Mahy

The Lost Thing by Shaun Tan, in which the ‘lost thing’ is a robotic creature as well as ‘the ability to really see what’s around us’.

The Lost Thing by Shaun Tan, in which the ‘lost thing’ is a robotic creature as well as ‘the ability to really see what’s around us’.

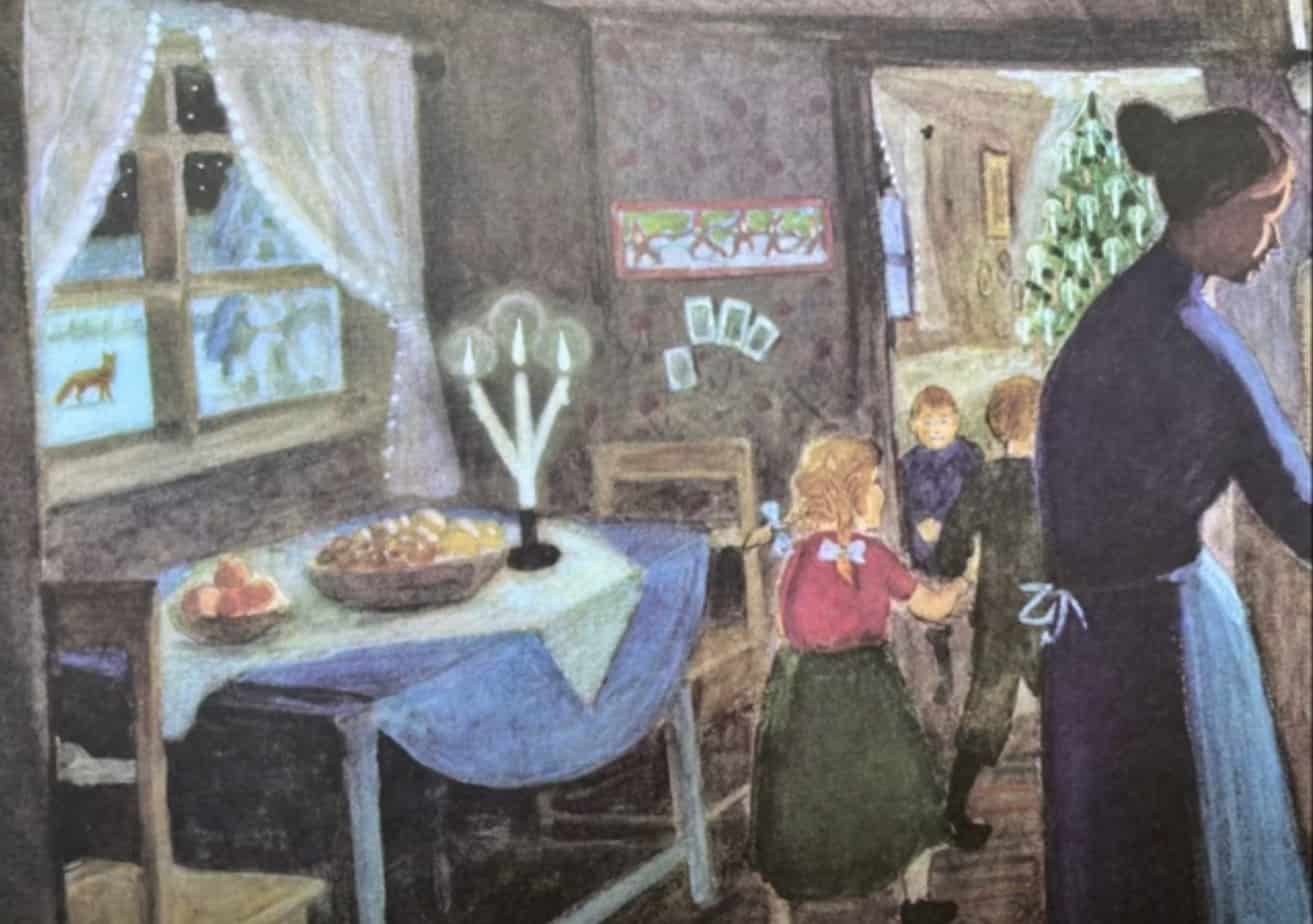

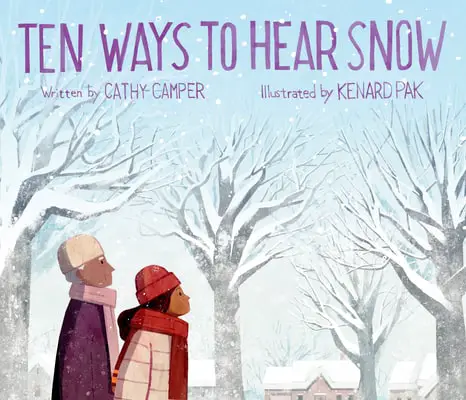

A snowy day, a trip to Grandma’s, time spent cooking with one another, and space to pause and discover the world around you come together in this perfect book for reading and sharing on a cozy winter day.

One winter morning, Lina wakes up to silence. It’s the sound of snow — the kind that looks soft and glows bright in the winter sun. But as she walks to her grandmother’s house to help make the family recipe for warak enab, she continues to listen. As Lina walks past snowmen and across icy sidewalks, she discovers ten ways to pay attention to what might have otherwise gone unnoticed. With stunning illustrations by Kenard Pak and thoughtful representation of a modern Arab American family from Cathy Camper, Ten Ways to Hear Snow is a layered exploration of mindfulness, empathy, and what we realize when the world gets quiet.

The concept of universal childhood is a Romantic abstraction which ignores the real conditions of children’s communication across borders. There is no ‘world republic of childhood’ in which the conditions are in any way on a par with one another…The vision of the universal child, the same the world over, refuses to acknowledge difficulties and contradictions in relation to childhood, offering in their place a glorification of the child, cast in the role of innocent saviour of mankind in a tradition which reaches back to Rousseau’s Emile with its creed that with every child humankind receives another chance for positive renewal.

Comparative Children’s Literature by Emer O’Sullivan

The Ideal Child Of The Imagination

Children often appear as angels in Christian iconography. (This is why cherubs have wings.) But as noted in the tweet below, cherubs have a certain creepiness to them. This is because of their history as scary creatures.

When parents are expecting a child, the child as a personality exists only in the imagination. This lasts for a few years into parenting. I remember the words of a mother whose own child had died saying that one of the most difficult parts of this grief was, to her, seeing preschoolers. The reason she gave? This is the time in a child’s life when anything at all is still possible. We have so many hopes and dreams for our young children. We never imagine that they won’t make it to adulthood.

This theme tends to be covered in work for adult readers. The short stories “The Child” by Ali Smith and by “Ernestine and Kit” by Kevin Barry are macabre tales about how adults become disappointed in children.

However, look outside the English speaking world and you occasionally find a story for kids with this exact theme: An exploration of the difference between what a parent hopes for and what they actually get. An example is Ivory Coast picture book Le Bébé de Madame Guénon [Mrs Monkey’s Baby] published 2009.

A monkey mother worries about her friends’ reactions to the beautiful baby she has just given birth to. Will their compliments be sincere? And will their judgment be fair? Visits and compliments do not appease her anxiety: she must do everything to make her baby even more beautiful! …The story plays

The World Through Picture Books

on the animal’s parade and the repetition of visit scenes, but its gist is indeed the terrifying anguish of mothers who dream of an ideal child.

Child As The Opposite Of Work

As Diane Purkiss points out in her book Troublesome Things, ideas about the child changed in the Romantic era (approx, 1800-1850), when childhood became a safe refuge from the harsh realities of life. Childhood became the opposite of work. It was thought that the very happiest way to spend a childhood was safe, carefree in the country.

But the Romantic invention of the child as the holy innocent coincided with growing child poverty, urbanisation and child prostitution.

While Wordsworth and Dickens were extolling the purity of the child, actual children were working from dusk til dawn. Victorians were faced with reconciling this harsh reality against their imaginary, idealised version of childhood.

See also: City Kids, Country Kids in Children’s Literature

If we compare Americans and French, it seems as though the relation between childhood and adulthood is almost completely opposite in the two cultures. In America we regard childhood as a very nearly ideal time, a time for enjoyment, an end in itself. The American image of the child…is of a young person with great resources for enjoyment, whose present life is an end in itself. With the French…it seems to be the other way around. Childhood is a period of probation, when everything is a means to an end, it is unenviable from the vantage point of adulthood.

Childhood In Contemporary Culture, Wolfenstein (1955)

Child as Idle Mischief Maker

1840s England was especially worried about idle children, especially street children. This was a class and race issue. It was thought that without something to occupy children, they would get up to mischief.

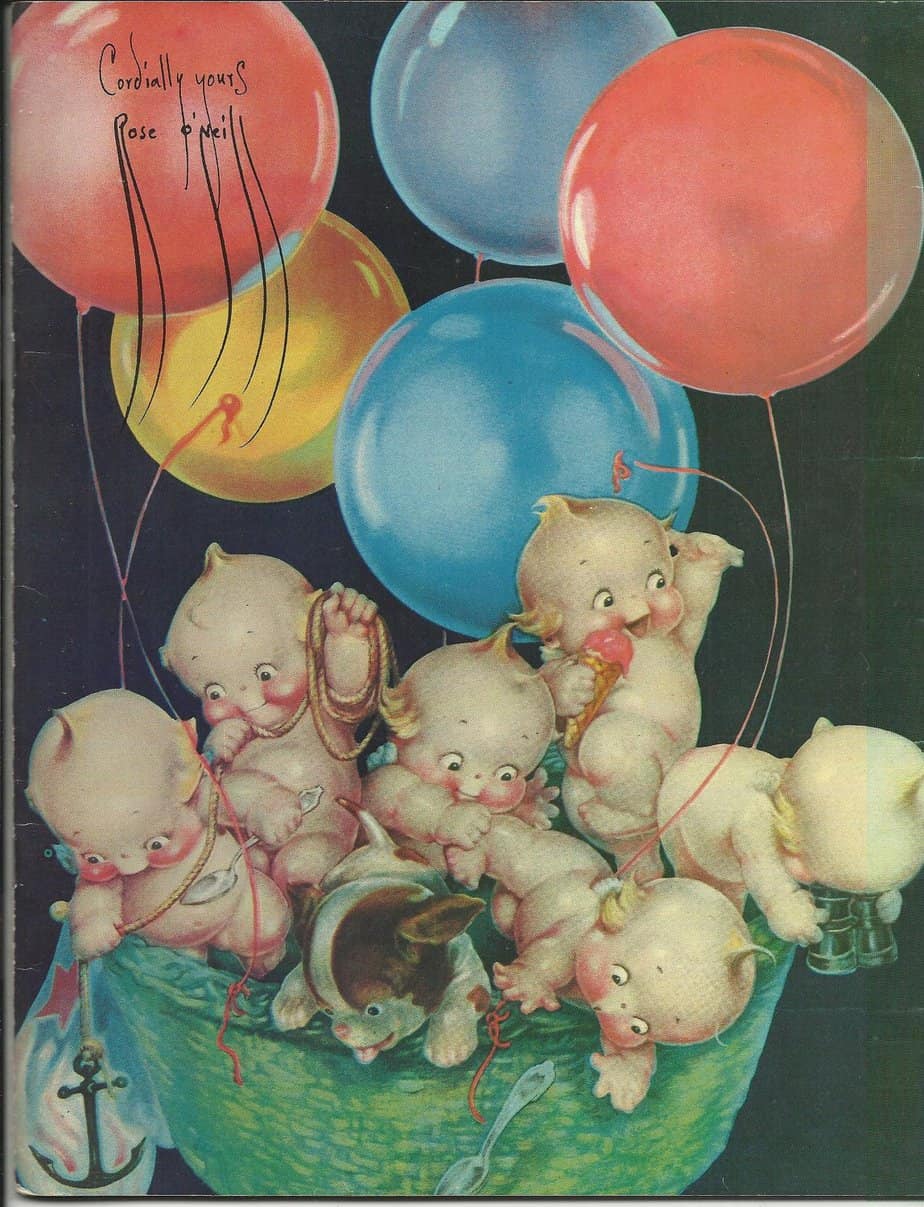

Child As Cherub

The Kewpie dolls (and related merchandising) were clearly modelled on classical images of cherubs.

Children originate in the Hebrew Bible as kerubim and often appear as cherubs in Baroque grotesque.

Putto is an Italian concept similar to the cherub but is not religious in origin. (The plural is putti.) The main difference is whether or not the cherubic creature has wings. Whereas all cherubs have wings, not all putti have them. In Baroque art the putto came to represent the omnipresence of God.

Some fauns are also depicted as cherubs but with hooves.

These characters are almost always boys. Significantly, the Italian word putto comes from the Latin word putus, meaning “boy” or “child” — boy as every child. (Boys are regular humans but girls are extra.)

Interestingly, the word cherub comes from kerub. Kerubim were completely different from today’s cherubs — imposing winged creatures who existed to guard the thrones of Gods and kings as well as the Mesopotamian Tree of Life. These Kerubim are described in the Book of Ezekiel (Old Testament). They are scary chimeras, each with a different head: lion, bull, eagle and human. These kerubim later became symbols for the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John (New Testament).

This is interesting because scary mythical creatures are quite often evolved by storytellers into something much more tame and pleasant. In this case, scary winged creatures become chubby-cheeked children. In the case of scary femme-coded mythical creatures, storytellers turn them into sexual objects. Sirens are an excellent case study of this. Witches, too, are often rendered as sexy rather than scary old hags in modern storytelling.

The witch/kerubim genealogy together demonstrate how women have been disempowered, alongside children, across the history of myth: Sexually alluring young women have had their scariness stripped away. Likewise, cherubim have had their adult-sized ferocity stripped away. Iconography without ferocity is more comfortable.

Freud’s View Of Children

Influential psychoanalysts have influenced our collective view of the child.

Erich Fromm succinctly summarises Freud’s thoughts on children in general. See what you make of this:

An assumption Freud makes about the nature of dreams is that these irrational desires which are expressed as fulfilled in the dream are rooted in our childhood, that they once were alive when we were children, that they have continued an underground existence, and have come to life in our dreams. This view is based on Freud’s general assumption of the irrationality fo the child.

To him the child has many asocial impulses. Since it lacks the physical strength and the knowledge to act on its impulses, it is harmless and no one needs to protect himself against its evil designs. But if one focuses on the quality of its strivings rather than on their results in practice, the young child is an asocial and amoral being. This holds true in the first place for its sexual impulses. According to Freud, all those sexual strivings which, when they appear in the adult, are called perversions are part of the normal sexual development of the child. In the infant the sexual energy (libido) centers around the mouth, later it is connected with defecation, and eventually it centers around the genitals. The young child has intense sadistic and masochistic strivings. It is an exhibitionist and also a little “peeping Tom.” It is not capable of loving anyone but is narcissistic, loving only itself to the exclusion of anyone else. It is intensely jealous and filled with destructive impulses against its rivals. The sexual life of the little boy and the little girl is dominated by incestuous strivings. They have a strong sexual attachment to the parent of the opposite sex and feel jealous of the parent of the same sex and hate him or her. Only the fear of retribution from the hated rival makes the child suppress these incestuous wishes. By identifying himself with the commands and prohibitions of the father, the little boy overcomes his hate against him and replaces it with the wish to be like him. The development of conscience is the result of the “Oedipus complex”.

Erich Fromm, The Forgotten Language

If Freud seemed to hate kids, bear this in mind: During the Victorian age, it was widely thought that children were wholly ‘innocent’. Children had no sexuality and were considered incapable of doing or thinking ‘bad’ things.

This was Freud trying to swing that pendulum the other way.

Jung’s Divine Child Archetype

If you’re reading a story with a child in it, and the child doesn’t seem to be a rounded person, functioning more like a bearer of ideology and ethics, this is Jung’s Divine Child archetype.

Jung noticed that all around the world we find stories about amazing children who survive against the odds:

- Baby Jesus in Christianity

- Child Moses in Judaism (Moses was not a real person; he didn’t exist.)

- Heracles in Greek tradition

- Horus in Egypt

- Buddha

- Krishna

But the Divine Child archetype has a reach in culture outside the stories of myth and religion. Mei from Studio Ghibli’s Totoro is an excellent example of the Divine Child archetype.

How is the Divine Child different from a regular child? We might invoke Northrop Frye here, who placed characters on a continuum from heroic to stupider than the audience. The Divine Child is basically a regular kid with the ability to come through against all odds. We love stories like that.

The Divine Child can’t easily be plotted on Northrop Frye’s continuum because they are both vulnerable and invincible at once. Stories starring the Divine Child are reassuring because there is a contract with the audience from the start — although this character is sufficiently vulnerable to make a good story, their secret superpowers will allow them to win out in the end. This story will end happily.

Jung considered the child as coniunctio between the unconscious and consciousness. If you dream of a child that’s meant to indicate some great spiritual change is about to take place under favourable circumstances.

The idea that we are surrounded by the extraordinary yet remain blind to it is a pretty common theme in picture books, in which the archetype of The (Jungian) Child is useful as a character who hasn’t lost their wonder yet, after being subjected to the monotony of life with adult responsibilities. “Children who notice things adults don’t” could be a subcategory of children’s literature in its own right. Think of all those fantasy portals, never discovered by adults, and all those fantasy creatures. Are they fantasy or real? Are they only real if we see them? What does it even mean to be ‘real’?

Shaun Tan makes use of this trope in “The Lost Thing” (adults don’t notice what children do) but inverts it for “Rules of Summer” (in which children are too busy arguing and watching TV to really enjoy the magic of a summer childhood).

There is some realworld truth to the idea that children see things adults cannot. Professor Alison Gopnik specialises in child psychology. In this podcast from All In The Mind, Gopnik explains exactly how children are better at noticing than adults. Babies and young children are built to explore the world and learn about it, whereas adults have better control of our focus. Therefore, as humans grow older, we become less good at learning about the world and better at executive functioning. Our powers of observation diminish accordingly.

Child As Heroic Figure

The heroic child liberates the world from monsters. A lot of picture books feature this kind of child. Mostly they are ridding their own minds from imaginary monsters rather than saving The World, but within the world of the story these monsters do exist.

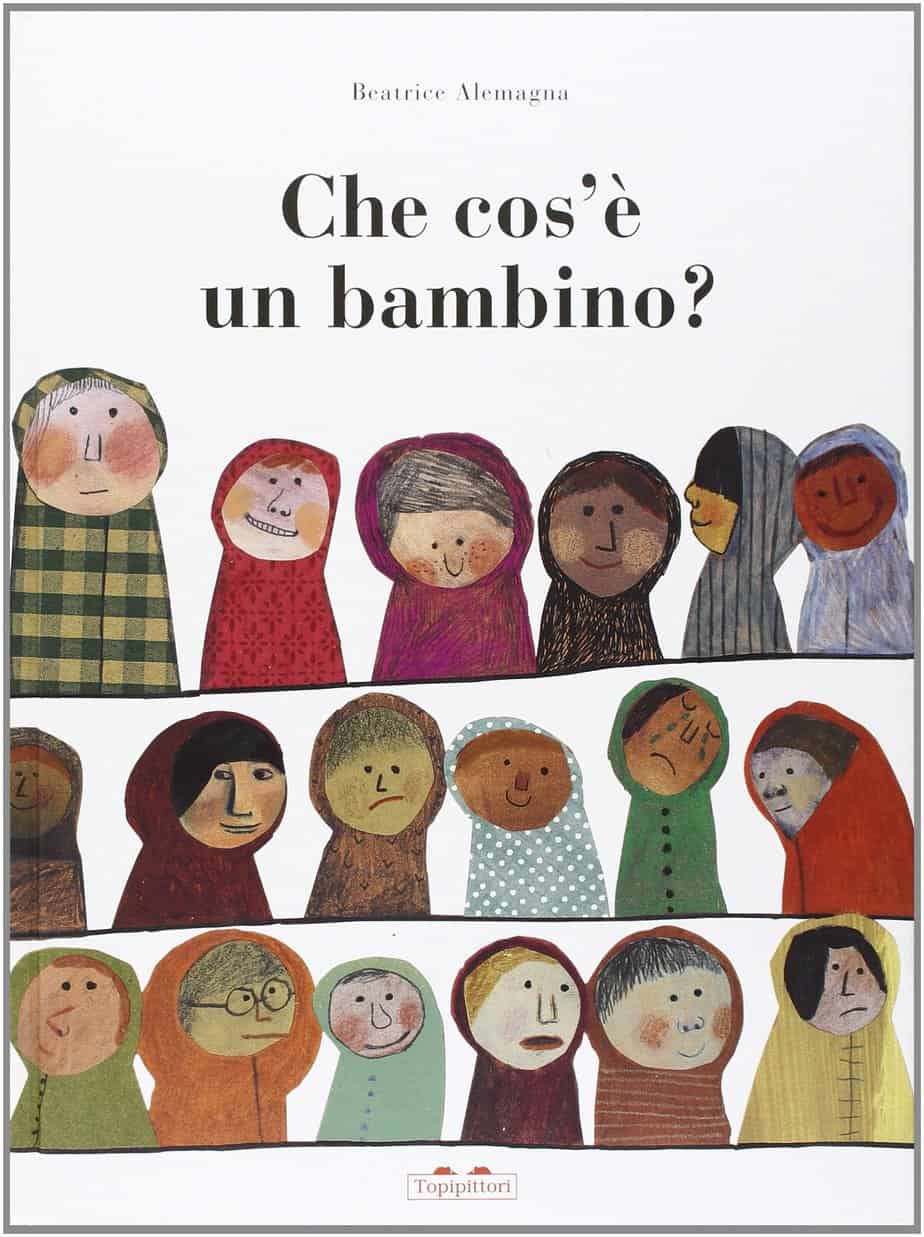

A child is a small person. He lingers small just for a while, then he becomes an adult. He grows up without even noticing it.

Beatrice Alemagna, What is a child?

Child as Coward

Go back to the Ancient Greeks, however, and they thought that cowardice separated adult from child: Adults were brave, children were cowardly. Socrates pointed out that our fears originate in childhood, and that we fear death because the child in us is frightened of hobgoblins.

In other words, if an adult is frightened, it must be the ‘child within’, not the actual adult. In many cultures and subcultures, fear is not an acceptable emotion for an adult to express. The closest we can come is to attribute fear to an inner child.

Ancient thinkers really did think that fear was a demon, and in order to escape fear, one had to escape actual demons.

Child As Eternal Life

Alchemy is an ancient art practised in Ancient Egypt, China, India and more ‘recently’ in medieval Europe. Alchemy concerned with two main things: working with real substances and working on one’s own spiritual / personal development / enlightenment. It was highly secretive and full of symbolism. At the heart of this art is the belief that there exists a mysterious legendary substance called the philosopher’s stone. This object is said to transform base metals such as lead into gold.

In Alchemy, the child wearing a crown or regal garments is a symbol of the philosopher’s stone. Important: the gold itself isn’t just gold — the gold symbolises enlightenment and eternal life.

It makes sense that children become associated with eternal life because if it were possible to never grow old, we’d probably remain as children. Although disease and circumstance does take the life of children, we associate death with old age.

The stand-out example of Child as Eternal Life is of course Peter and Wendy. J.M. Barrie did something interesting by flipping dominant ideas about the tragedy of failing to become an adult. Since antiquity, failure to become an adult had been seen as a tragedy. We see this in Greek and Roman mythology. To remain childlike is a tragedy because to remain a child is to remain forever dependent upon others. But then J.M. took that idea and flipped it — now, to become an adult was the tragedy because adulthood meant you lost your true self. It’s interesting to observe that this fantasy of perpetual childhood has been left behind (for now) to languish in the 20th century. This article explains that since copyright expired on Peter and Wendy in 2008, we’ve seen a surge of retellings in which to remain a child is rendered, almost unanimously, as dark and creepy. Peter Pan is now the villain.

Woman As Child

Patriarchy works by rendering women as children in the public imagination. Until very recently, women were considered children in the eyes of the law. It’s not difficult to find evidence of this view right across storytelling.

To make a more universal statement, however, the hero’s journey provides a classic example of the difference between men and women across mythic stories. Men leave the house, encounter a variety of friends and foes then eventually prove themselves in battle. He’ll have weapons of some kind at his disposal.

The female corollary is childbirth. The heroine of these stories never leaves home. She has no weapons at her disposal, entirely vulnerable to her own physiology. The pregnant and birthing woman’s vulnerability renders her childlike. In both stories, the man and the woman come close to death. Both offer up their bodies for the sake of some greater good. But because the hero gets weapons, gets to make decisions, he is afforded symbolic autonomy.

Take a close look at how weapons are used in stories, who gets them, who uses them. Next, consider the genealogy of modern gun culture.

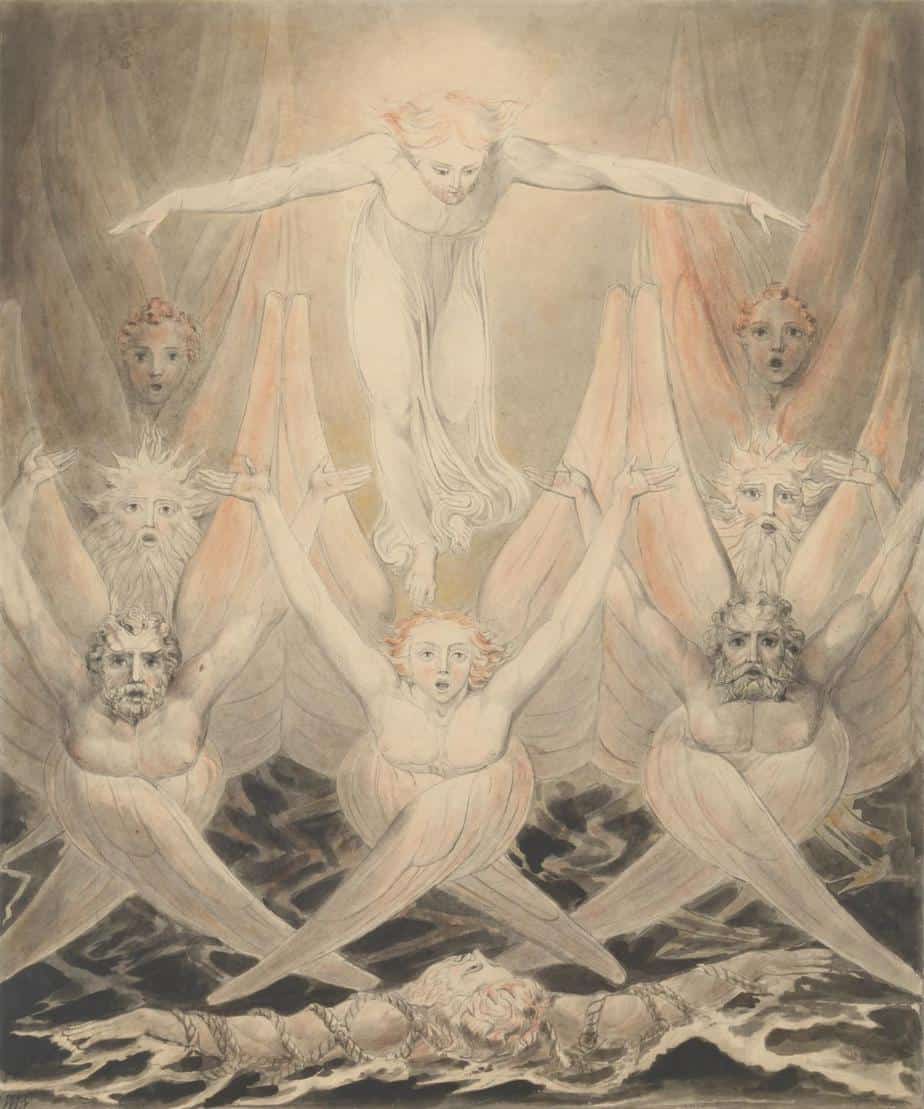

Header image: William Blake’s David Delivered out of Many Waters, c.1805. It is an illustration to Psalm 18, in which David (at the bottom of the image with his arms stretched wide) calls out to God for salvation from his enemies. Christ appears above, riding upon seven cherubim (angels), not one as in the text.

Child As Other

Granny bit her lip. She was never quite certain about children, thinking of them – when she thought about them at all – as coming somewhere between animals and people. She understood babies. You put milk in one end and kept the other end as clean as possible. Adults were even easier, because they did the feeding and cleaning themselves. But in between was a world of experience that she had never really enquired about.

Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites