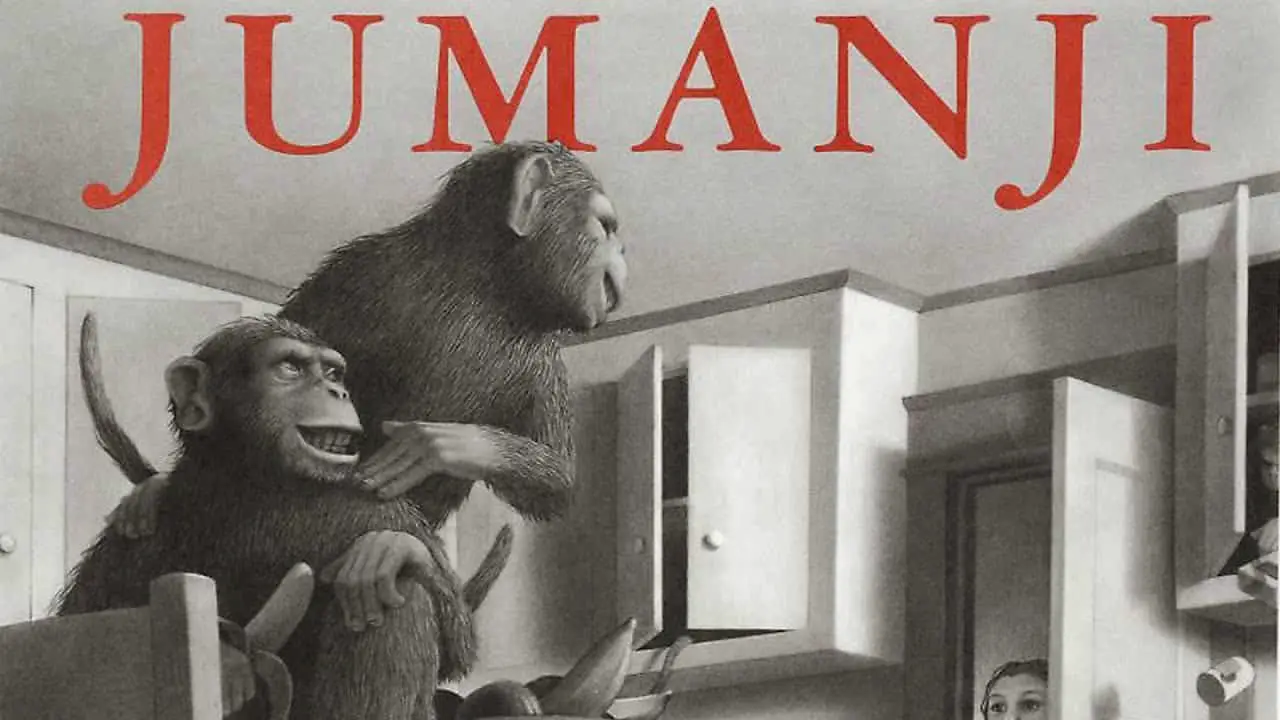

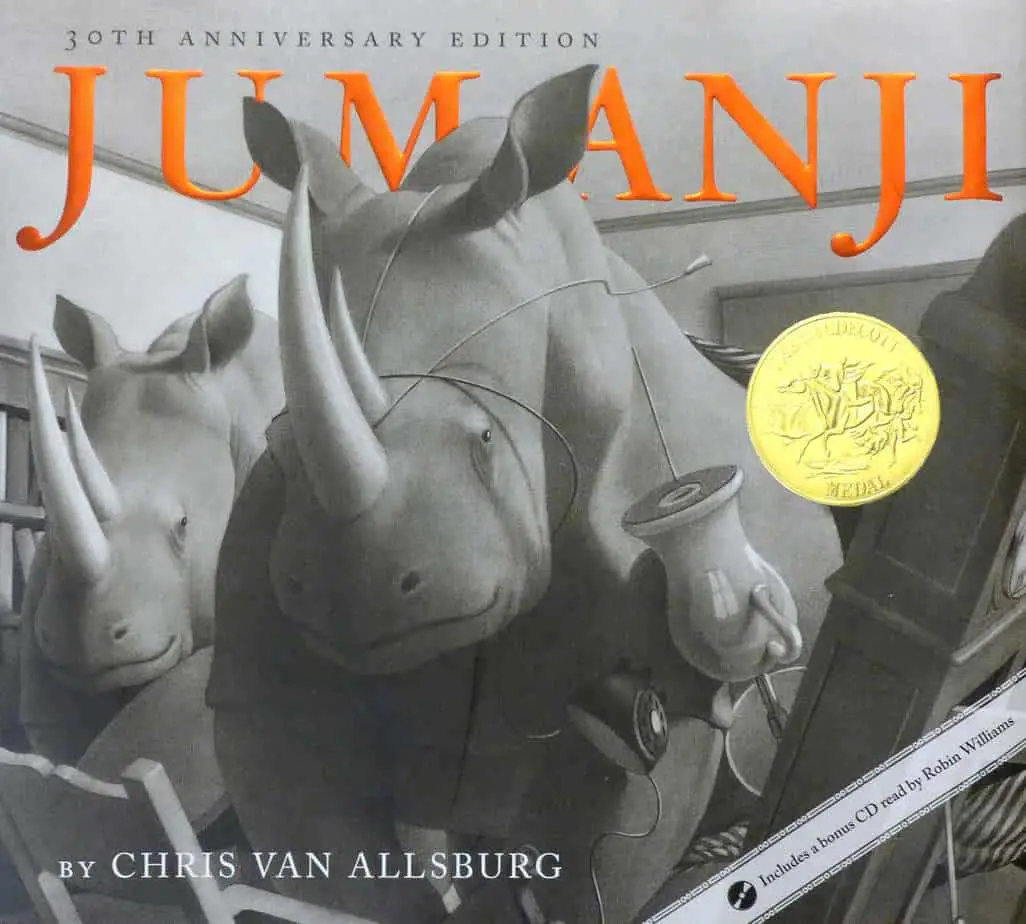

Jumanji is a 1981 picture book written and illustrated by American storyteller Chris Van Allsburg. You may be familiar with the 1995 film adaptation starring Robin Williams.

Chris Van Allsburg has said that this story started with imagery. He wanted to put unexpected things together, such as a rhino in a living room. He describes the effect on readers as ‘cognitive dissonance’.

Cognitive dissonance: the state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioural decisions and attitude change.

Another descriptor for the Jumanji variety of art is Surrealism. Artists have been juxtaposing unfamiliar objects for many years. The Surrealist art movement began around 1920, inspired by Sigmund Freud’s theories of dreams and the unconscious. Freud’s personal favourite Surrealist painter was Spanish painter Salvador Dalí.

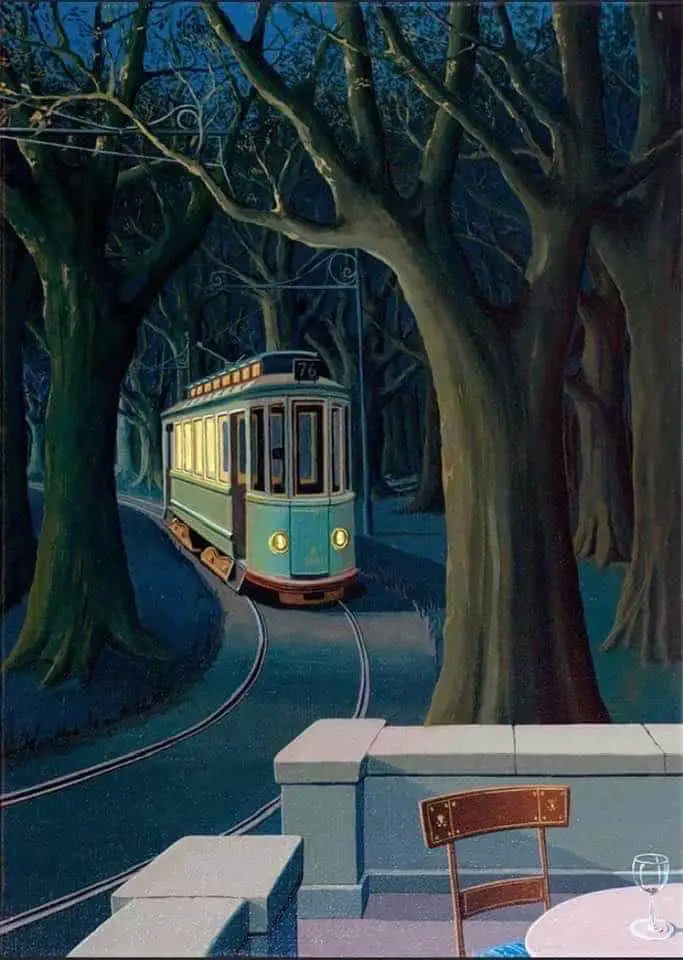

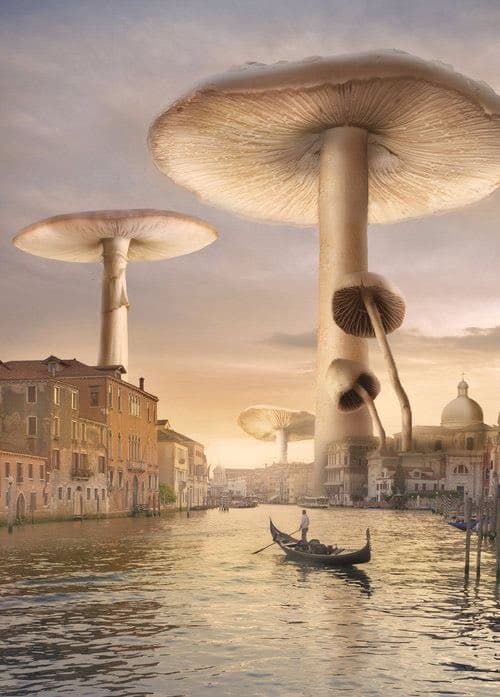

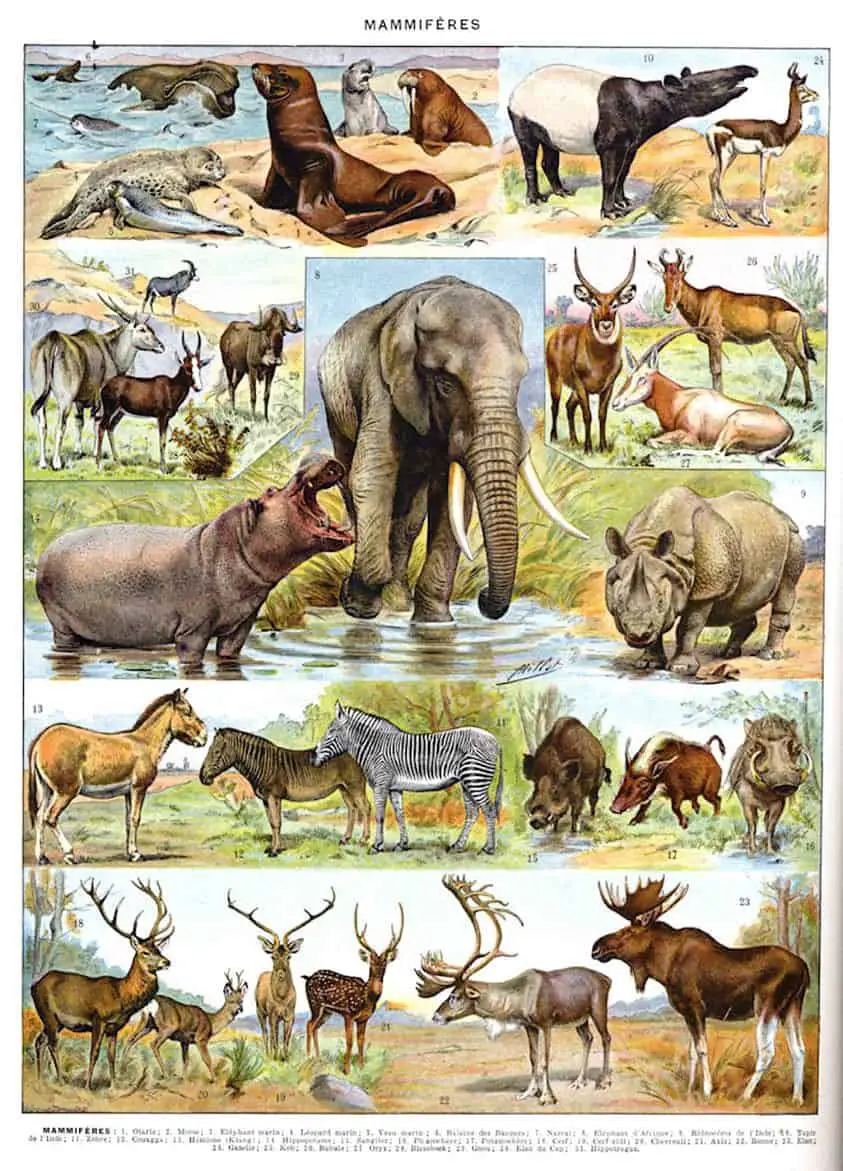

Contemporary artists continue to work in Surrealist style. Check out the paintings of Vladimir Kush below, who also places unexpected things togethe, creating a new world:

In art, Surrealism has a specific meaning. A Surrealist work aims to get the viewer in touch with their subconscious and uncover deeper truths. A Surrealist work isn’t supposed to confuse; it is meant to reveal.

Surrealist art also has a defamiliarsing effect. In Jumanji, an ordinary living room seems different because it has rhinos in it, and a flood, and monkeys. What will defamiliarisation reveal to these children, and therefore to the reader?

SETTING OF JUMANJI

The American suburban home of the early 1980s is the predictable ‘theatre’, meaning a type of fictional setting where the expected always happens. Two children deviate from that theatre by playing a dark-magic game they find in the park across the road.

Elements of the storybook jungle thereby come into the cosy picture book house, upsetting expectations of safe and expected. It’s significant that the boardgame looks like hundreds of others they’ve seen before, but it isn’t.

The American suburbs are an interesting horror space, because they rely on the Snail Under The Leaf setting: Everything looks lovely… on the surface. But lift a leaf in the park and you’ll find a nasty, unexpected little snail. (No shade on snails.)

Before the story begins, Van Allsburg gets parents out of the way, explicitly the mother, who has organised a big trip to the opera. The kids will be entertaining themselves at home, but then they trot off to the park.

The 1980s were a different time. At the age of six or seven, my friend and I would go down to the park at the end of the street and climb trees. I sometimes think about how I’d never let my own Gen Z kid do that, and if I did, I’d risk social censure.

STORY STRUCTURE OF JUMANJI

PARATEXT

The game under the tree looked like a hundred others Peters and Judy had at home. But they were bored and restless and, looking for something interesting to do, thought they’d give Jumanji a try. Little did they know when they unfolded its ordinary-looking playing board that they were about to be plunged into the most exciting and bizare adventure of their lives.

In his second book for children, Chris Van Allsburg again explores the ever-shifting line between fantasy and reality with this story about a game that comes startingly to life.

His marvelous drawings beautifully convey a mix of the everyday and the extraordinary, as a quiet house is taken over by an exotic jungle.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

Peter is the kid whose shortcomings will be tested in this book: He is easily bored and makes the grave mistake of assuming that if this new thing resembles old things, the new thing is exactly the same as the old things.

DESIRE

The 1980s were a time of freedom, and also of great boredom. I’m not going to romanticise it; some of this boredom wasn’t creatively stimulating, it was simply mundane. Without the Internet or cable TV some days really did feel interminable, even though 80s kids were relatively good at entertaining ourselves.

This story, like many others for children, starts from a place of boredom. But it does come from a different era and I’m wondering how much longer children’s storytellers can realistically use boredom as an instigator for adventure. For contemporary children, boredom can almost always be assuaged by use of screens. If Van Allsburg had written Jumanji today he would have had to disappear screens as well as the parents.

OPPONENT

The brother and sister are set up as arhetypal gendered boy and girl (the boy plays with a train, the girl with a dollhouse), and throughout this story they contrast in their approach to this magical, dangerous thing that’s come into their home.

Like almost every storyteller of this era, Van Allsburg defaults to gender essentialist notions of boys vs girls: The girl wants to follow the instructions; the boy does not. This story belongs to an era which eventually led to a raft of ‘humorous’ self-help books e.g. Why Men Don’t Listen And Women Can’t Read Maps (1998). These were displayed prominently in the big box stores when I was growing up and were therefore bestsellers. The notion that girls are naturally more compliant and better at following rules than boys is a very old one. Of course, this very story is a prime example of how the gender model is absolutely everywhere, so if girls are better at following rules, it’s at least partly because expectations are different. (In a binary culture, we are all punished by failing to conform to the gender binary.)

“Put those down and listen,” said Judy. “I’m going to read the instructions.”

Jumanji, exemplifying the ‘girls as little mothers’ principle.

What’s interesting in light of more recent feminist thought: It turns out in this case that the girl is correct within the veridical world of the story. The brother and sister should have read the instructions; they did need to finish the game. When girls do research and save the day, I call this the Hermione archetype, a modern form of feminism in which girls are smart, even if their smarts can make them initially unappealing. This Female Maturity Formula is utilised by Pixar et al. In light of more recent revelations, no one should be learning feminist thought via a J.K. Rowling character.

Because was Jumanji’s Judy character really ‘right’ to suggest they read the instructions? Was it not Peter’s shortcomings that instigated the adventure? The animals are wild outworkings of the children. This is established with the image of the lion on the piano, yawning as Peter declares how bored he is.

As has been said of road trip stories (a massive genre in America, with a history that stretches right back to the Bible): Although the traveller risks his very life by deviating from the expected route, he also misses out on personal growth and a valuable metaphyisical experience. (I use ‘he’ for a reason.) The ‘boy’ way of doing things may be the more hazardous route, but his is also the more rewarding.

Thus, Van Allsburg’s boy vs girl way of approaching a new board game in this story represent two opposite ways of approaching life in general. Jumanji just so happens to be gendered in a predictable way; predictable because of its very long history. This ‘history’ is partly why we get the world leaders we’re stuck with today.

This dualistic/binary gendered approach to life is the main oppositional interest in this story, but to create a storyworthy level of tension we also have the Minotaur opponent of dangerous animals (culminating in the rhinos) and also a strange man, who is never known. We only get to see his back. He could be anyone.

The game itself could be considered an opponent, and like all worthy opponents, it has shaped itself around the greatest weakness of the children. “Designed for the bored and restless” say the instructions. It’s easy to imagine in this magical realist setting that if other children found it, the game would poke at their greatest weaknesses (selishness, greed or whatever).

Below is another example of an interior low angle perspective. This is a childlike point of view, as children tend to live more on the floor. In the example below, the adult has another reason to be sitting on the floor, of course:

PLAN

When they get bored, Judy and Peter decide to go to the park. That’s where they find the abandoned game. You’d think the previous people would’ve thrown it at the bottom of a trash can, wouldn’t you? Which of the neighbour kids put it there, hoping some other kids would be terrified out of their skulls? (No worries, this is a refrigerator thought.)

Peter and Judy decide to play the game. Well, it’s Judy’s idea. Peter mistakenly thinks it will be boring.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In contrast to, say, lyrical short stories, which often take an ellipical approach to a big struggle scene, the battle sequence of a carnivalesque picture book occupies most of the total space. This is true in Jumanji, as the wild animals and the man appear cumulatively in the children’s living space.

Peter has a near death experience when he falls asleep with his head on the table with ‘sleeping sickness’. (Metaphorical death.) This, more than any other detail, tells us this is mainly Peter’s story. He’s the one who will learn the lesson offered up by the story; Judy already knew it. In these stories, which go all the way back to Odysseus, the girl was mature all along. The boy is the main character because he’s the one who has the character arc.

There is of course room in the world for adventures starring boys. Here’s why I linger on this point: the (white) boy as main character comprises the overwhelming majority of total stories in the world. The existence of stories such as Jumanji can fool us into thinking we’re getting an ensemble piece, because a girl also exists on the page and gets plenty of the dialogue.

ANAGNORISIS

The girl insists that the instructions are read and that the game is finished. This is what saves them both. The story achieves a ‘never give up’ ideology.

I’m personally really sick of this storyline. This can look like girl power, but it isn’t. What we see happening at the highest levels, time and time again, is so common the phenomenon got its own name in 2004: the glass cliff. Patriarchies want powerful Strongmen in leadership roles. When these powerful men do reckless things, they often screw things up. Next, a woman is brought in as clean-up crew. If the situation is too late for her to save, the whole company/country falls off a metaphorical cliff and… guess who gets the blame for that. (The very nature of turn-taking in a boardgame ensures the girl remains solidly on the page.)

NEW SITUATION

In the case of Jumanji, the girl does indeed save the day with her cautious approach to new things, and insistence that they see the game through to its conclusion. The glass cliff ending is averted.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The appearance of the two brothers, seen from the advantageous, omniscient position of the upstairs window, shows that this story will play out again. This time, the consequences may not be so great. This is a classic example of a ‘repeating’ picturebook structure.

Jumanji is a surprisingly didactic story. It teaches kids to read the instructions before playing a game. It also teaches kids to finsih what they start. In boardgames it can be tempting to give up out of boredom (or when losing, frustration.) But that’s only a surface level interpretation. Chris Van Allsburg is doing in Jumanji what he does in all of his picture books: He is encouraging readers to take notice. Rather, he is urging children not to lose their childlike superpower of noticing what adults fail to see.

“It was on a low rock, shoulder height for Lily, and she just spotted it and said, ‘look Daddy,’” her mother Sally Wilder, 41, told NBC News by telephone on Saturday.

Four-year-old girl discovers 220 million-year-old dinosaur footprint at a beach in Wales

Is that what the Surrealism is all about, then? I believe so. By inserting a rhino into a living room, Van Allsburg makes the living room unfamiliar. We wonder what else might be under the sofa, on the bookshelf, in the kitchen cupboards. We start to view familiar surroundings with renewed caution and curiosity. Van Allsburg does not wish children to become unobservant.

This subtle ideology is partly a Peter Pan desire for never-ending childhood. Basically, growing up looks like this: When we are born we know nothing and can’t do much. As babies and toddlers interact with the world around them, their brains rapidly start pruning. This pruning is necessary — if it didn’t happen we might never learn to dress ourselves. We’d be so enchanted with every little leaf blowing in the wind. As we get older, all this useful pruning means we do start to lose our babylike fascination with the world. Adults achieve focus as a tradeoff. Some have suggested that the experience of psychedelic drug use returns us surprisingly close to the state of being a toddler. Van Allsburg’s rhinos in the living room may feel like a drug experience, but it is also a toddler-like experience of wonder and noticing and appreciating the world. In Jumanji, Peter both children have lost it, and by Van Allsburg’s reckoning, they have lost it prematurely.

RESONANCE

There is a solid corpus of fairytale and folklore about a character who finds a lucky thing out in the world, thinks all of their dreams have come at once, then finds their home (and entire life) invaded by something which is basically evil. Many of these stories feature a container of some kind: a magic lantern, Pandora’s box, sometimes teapots. Aladdin fairytales about the djinn (genies) work like this, too: Sure, it’s great to find something that grants as many wishes as you like, but you’ll come to grief unless you can learn to master your base shortcomings.

Storytellers of all forms continue to utilise this ur-story in various forms. Sometimes it’s not very obvious. Ali Smith’s short story “The Child” might even be a descendent of this type of fairytale. In that, case a woman finds a baby. The baby turns out to have a trash mouth on it.

Zooming out even further, good stories feature opponents who poke directly at the main character’s weaknesses, provoking growth. This is a universal narrative technique and these opponents are known as The Shadow In The Hero.

When Arthur, Ren and Cecily investigate a mysterious explosion on their way to school, they find themselves trapped aboard The Principia – a scientific research ship sailing through hazardous waters, captained by one Isaac Newton.

Lost in the year 2473 in the Wonderscape, an epic in-reality adventure game, they must call on the help of some unlikely historical heroes, to play their way home before time runs out.

Jumanji meets Ready Player One in this fast-paced adventure featuring incredible real-life heroes, from the internationally bestselling author of The Uncommoners series.