Leading up to 1918, Beatrix Potter’s publishers were asking her for a new story. This was wartime. Austerity all around. Frederick Warne and Co. were affected alongside everyone else and required something new from their bestselling children’s author. But Beatrix had moved to the country and the country was keeping her very busy.

Rather than come up with something wholly original, she chose to rewrite an Aesop fable: The Town Mouse & The Country Mouse. Potter personalised the mouse by giving him a name: The Tale of Johnny Town-mouse.

Is it ironic that Beatrix Potter glorified the country even while country life made her so busy she barely had time to write and illustrate anymore? Probably not ironic, given how post-purchase rationalisation works. Beatrix had moved the country and she’d enjoy every minute, dammit. And if she couldn’t convince herself on a daily basis, she’d write a book about it.

Actually, I have no idea what Beatrix Potter was thinking. That’s what I’d be thinking if daily chores left me with no time to write and illustrate. In any case, what’s writing for if not to cement your own ideologies?

…there was no quiet; there seemed to be hundreds of carts passing. Dogs barked; boys whistled in the street; the cook laughed, the parlour maid ran up and down-stairs; and a canary sang like a steam engine.

The ideology expressed in Johnny Town-mouse was echoed over and over throughout the 20th century by authors such as Enid Blyton and E. Nesbit. Towards the end of the 20th century children’s literature started to offer similar commentary on video games, connecting video games to the city, supposedly absent in rural areas. (I have news for those authors.)

More recent children’s books have turned the tables and as a member of Gen X I feel personally vilified — now children’s books feature parents staring at screens while the children are ignored, sometimes to disastrous effect, sometimes simply to allow modern kids an adventure.

Read Johnny Town-mouse as a prime example of ‘city bad—rural good’ ideology from the first golden age of children’s literature.

STORY STRUCTURE OF JOHNNY TOWN-MOUSE

Johnny Town-mouse has the structure of a mythic journey. The hero never wants to set out on adventure; instead he is thrust out into a dangerous world because he fell asleep inside a hamper.

SHORTCOMING

First up, why mice? We’d have to ask Aesop. Shame. He’s dead. However, we can guess why mice are so popular in children’s books. People have studied this stuff.

The Shortcoming of a mouse is the same as that of the Every Child — mice are small and vulnerable, though full of life, bravery and mischief. Mice will happily go off on an adventure. This also gets them into strife. In a children’s book, if a mouse leaves home, you can guarantee it’ll meet with life-and-death danger.

The opening of this story is a little bizarre (by today’s standards). Potter basically summarises the entire narrative in two opening sentences. These sentences feel disjointed to my ear:

Johnny Town-mouse was born in a cupboard. Timmy Willie was born in a garden. Timmy Willie was a little country mouse who went to town by mistake in a hamper.

There’s also the unpleasant word echo of ‘hamper’. I get the feeling this story really was rushed out. I suppose in war time there are bigger problems than a bit of word echo.

DESIRE

So Timmy Willie gets taken to town by mistake in a hamper.

Presumably he does not want to go to town. He’s horribly disorientated inside his wicker cage, borrowing from that cosmic horror trope we now have a word for: spatial horror. I’m noticing children’s stories use it frequently. Children (and mice) are so small they can get bundled up inside things and thrown around from movement, against their will, outside their control.

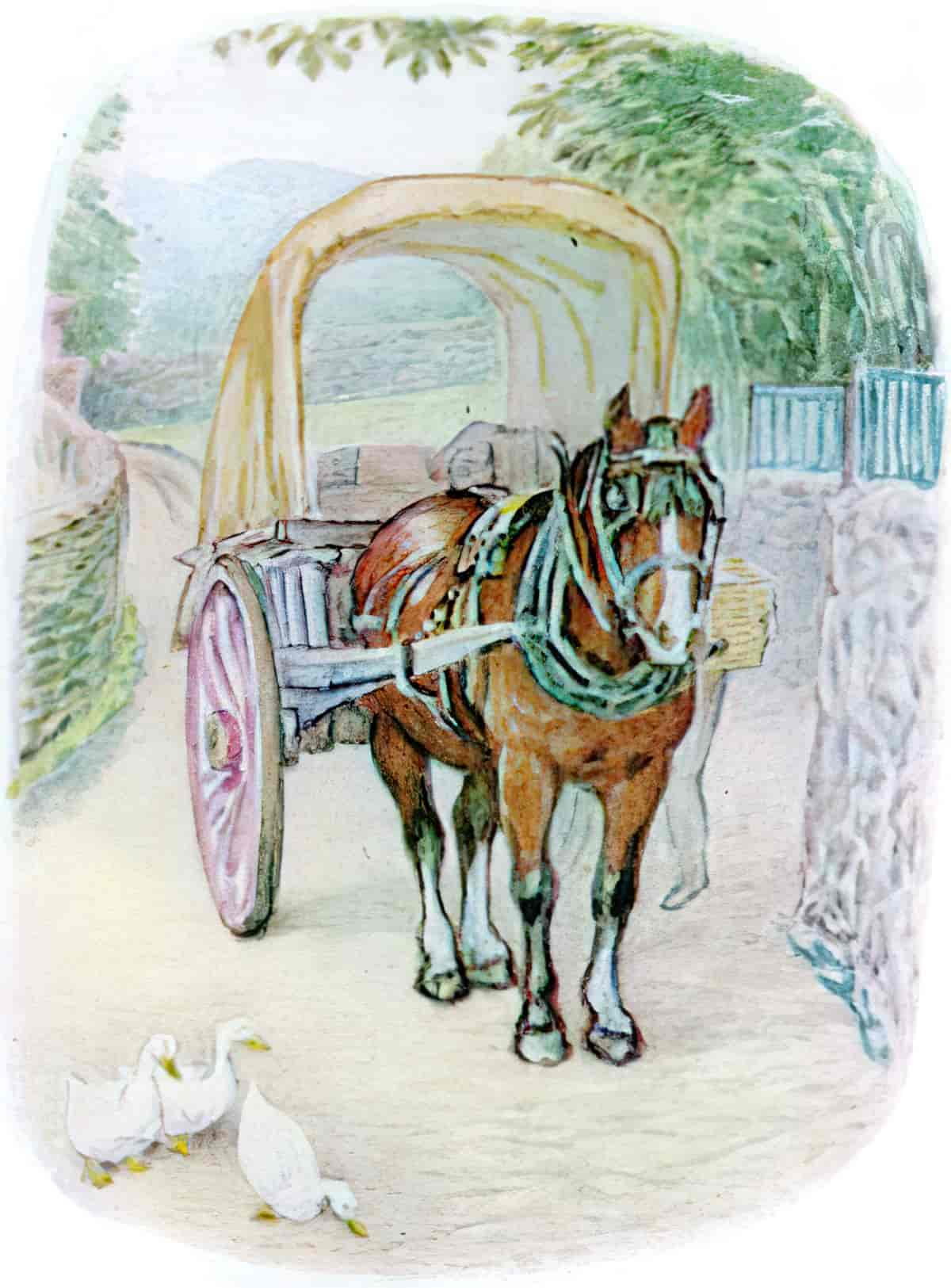

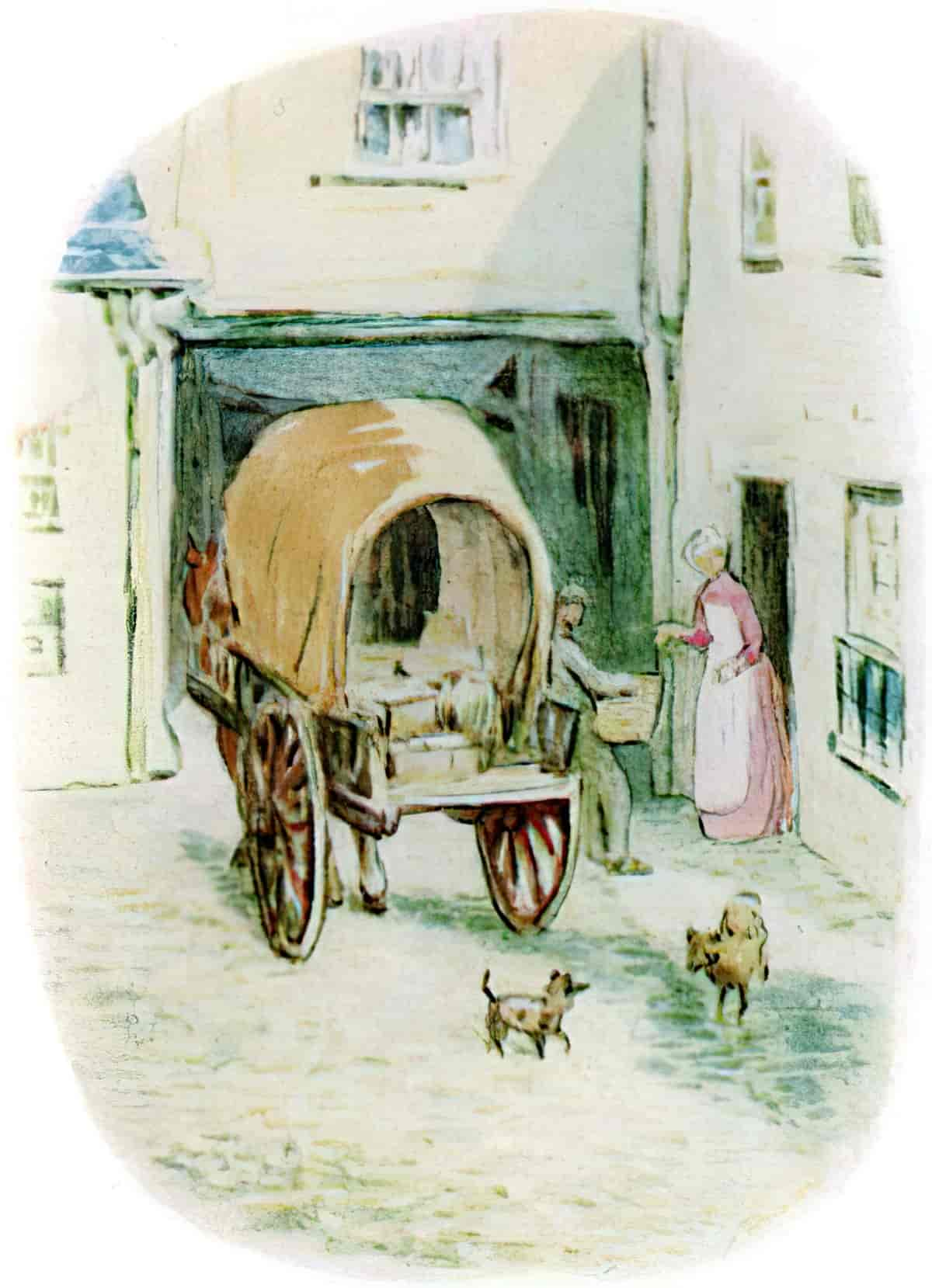

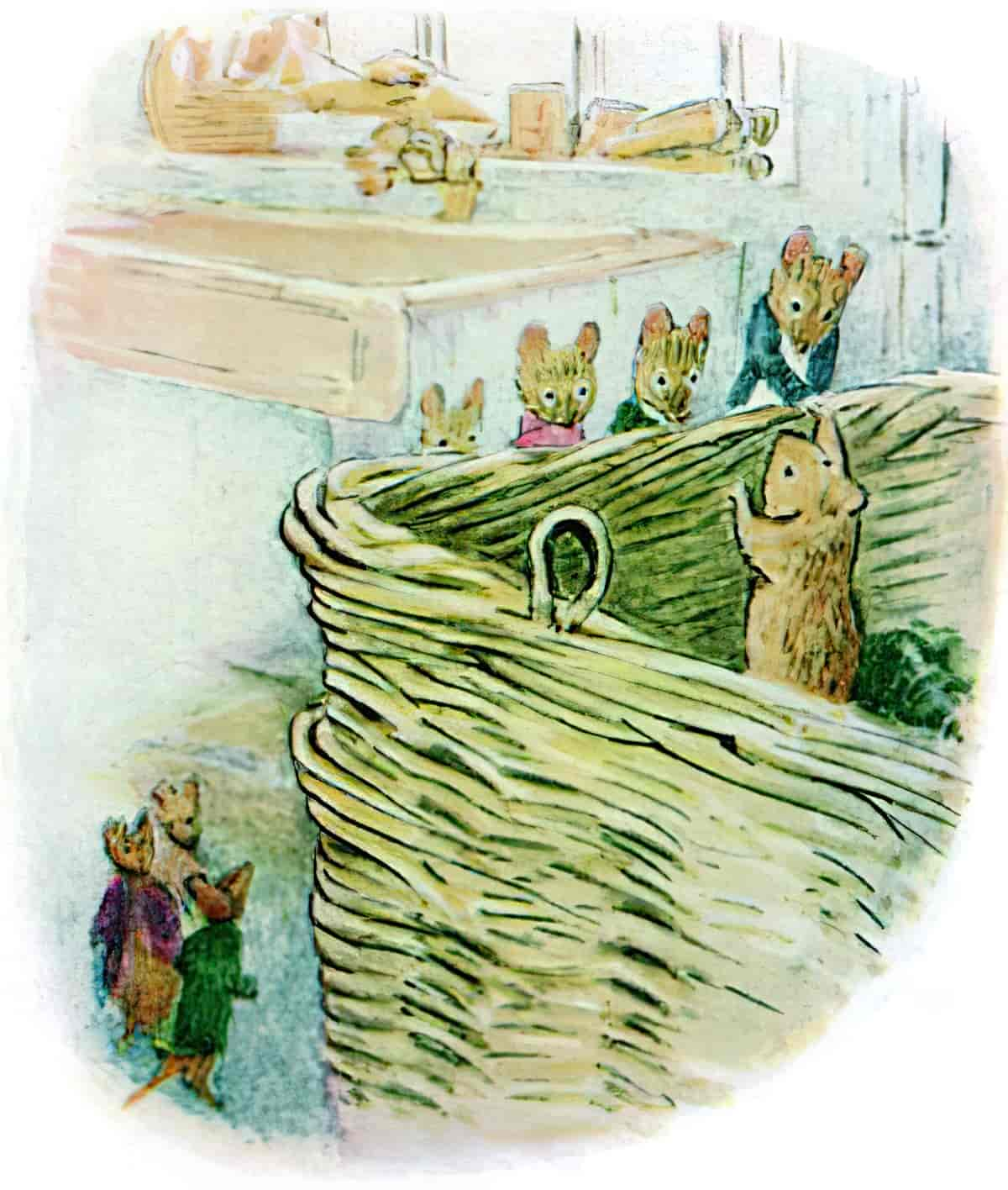

He awoke in a fright, while the hamper was being lifted into the carrier’s cart. Then there was a jolting, and a clattering of horse’s feet; other packages were thrown in; for miles and miles—jolt—jolt—jolt! and Timmy Willie trembled amongst the jumbled up vegetables.

OPPONENT

The “Minotaur Opponent” in this story is the cat, whose smell lingers as a pervasive threat. The cat doesn’t make for great dinner-time music, either:

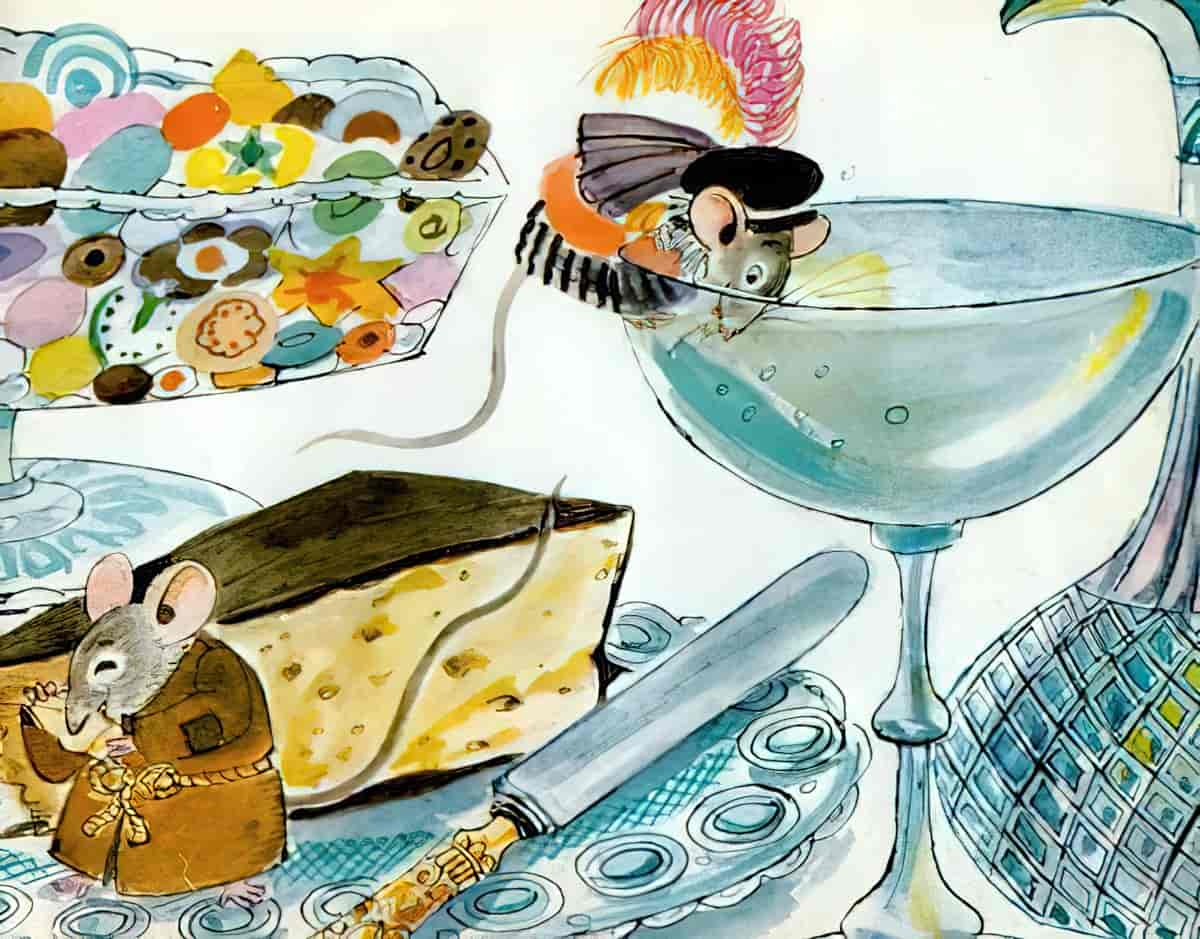

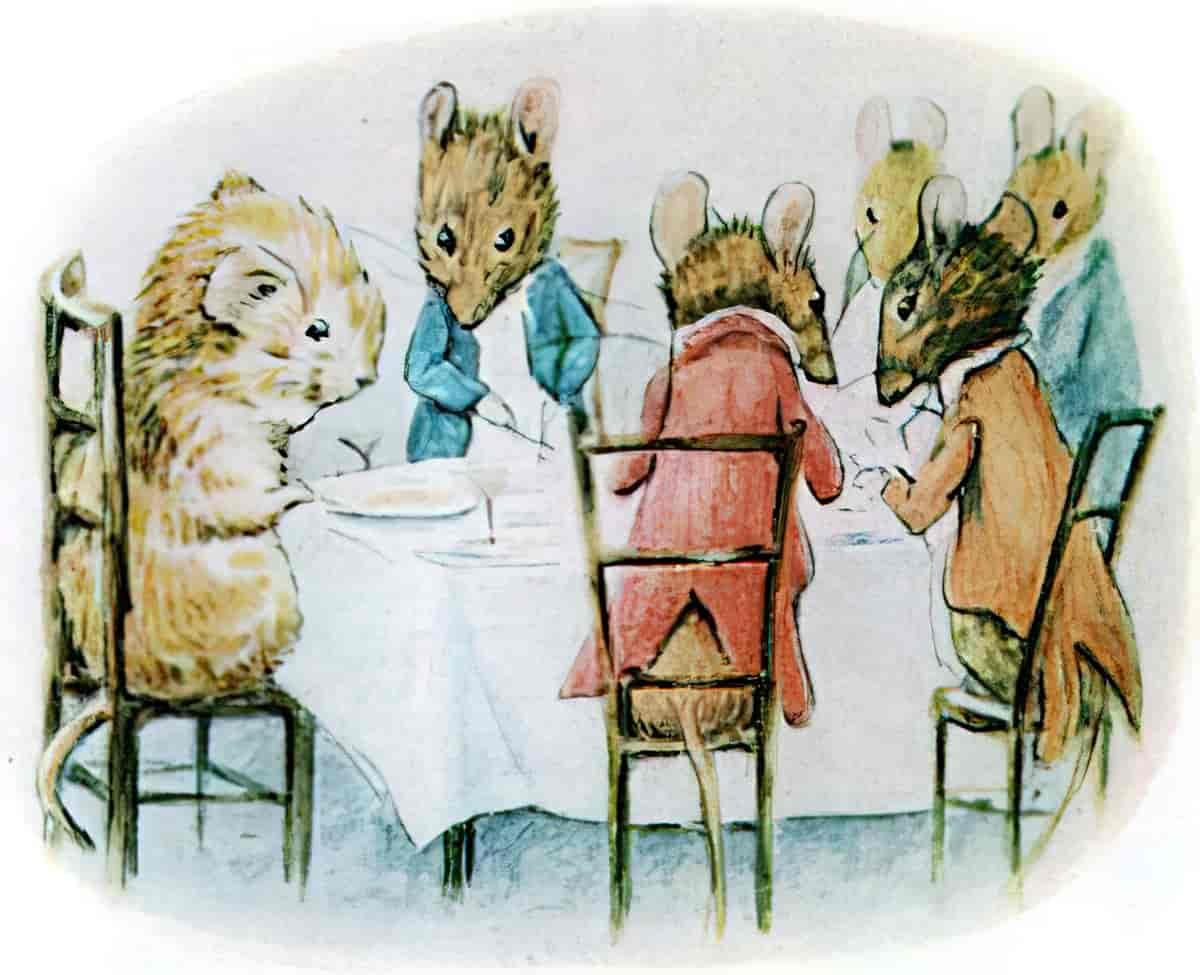

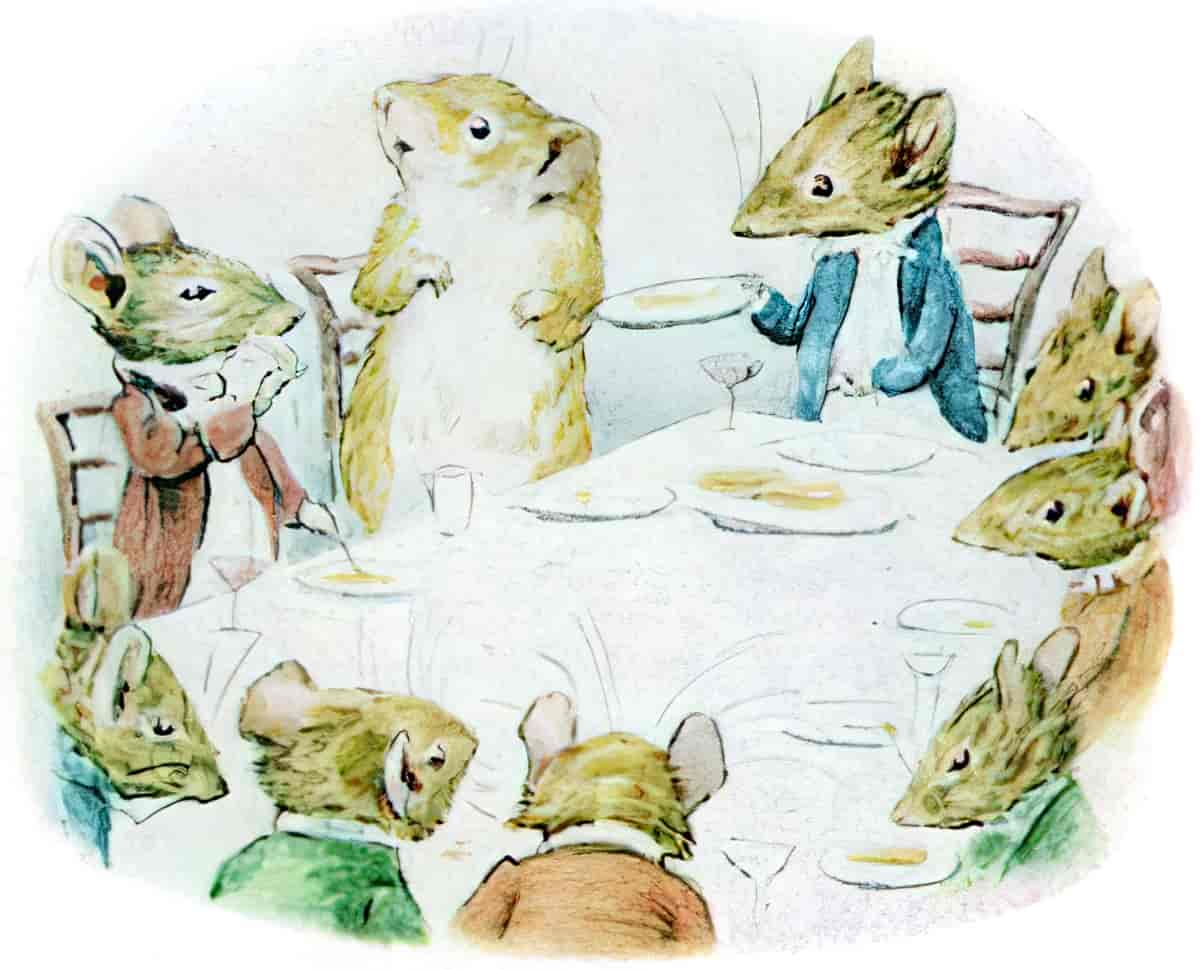

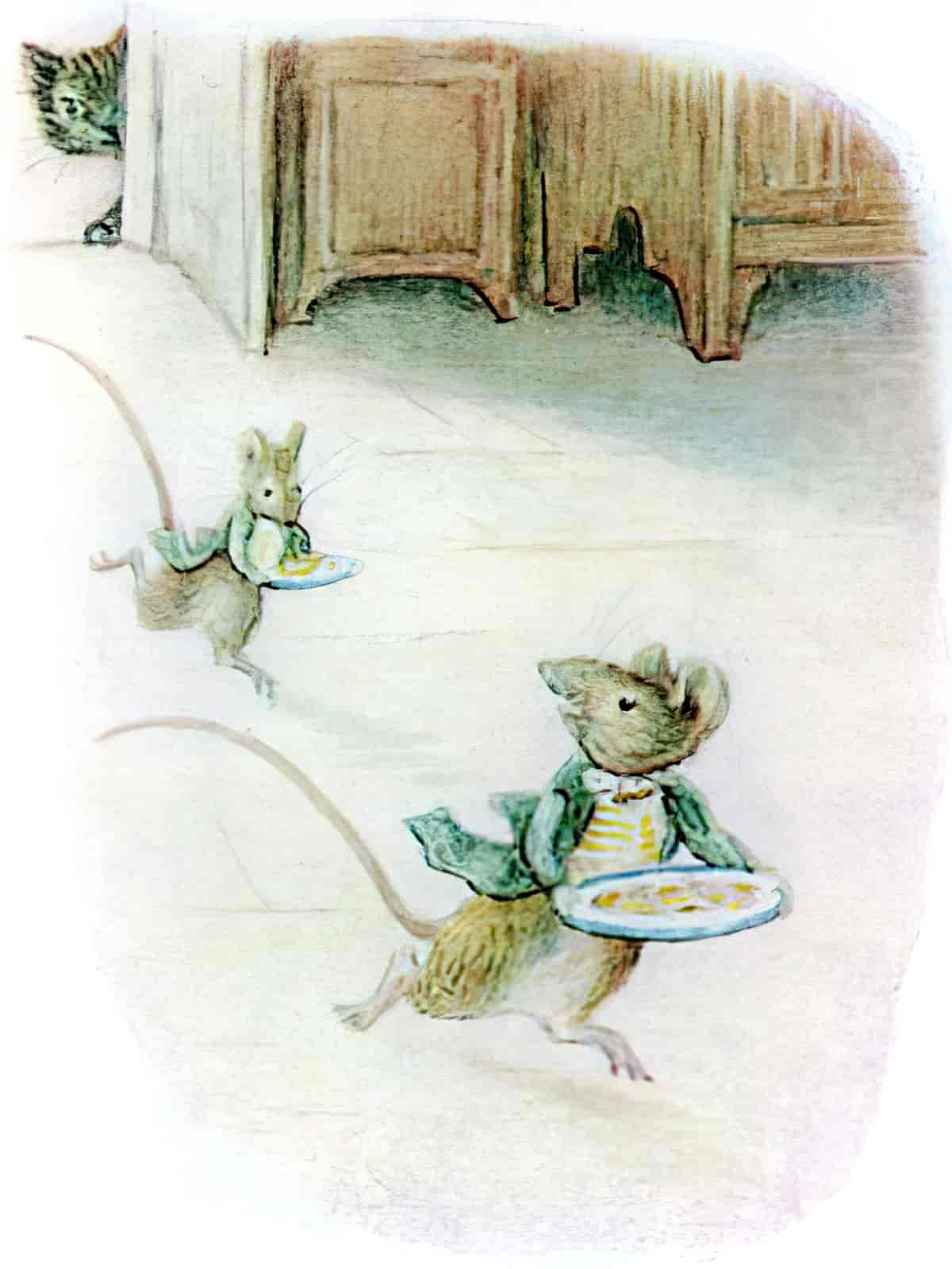

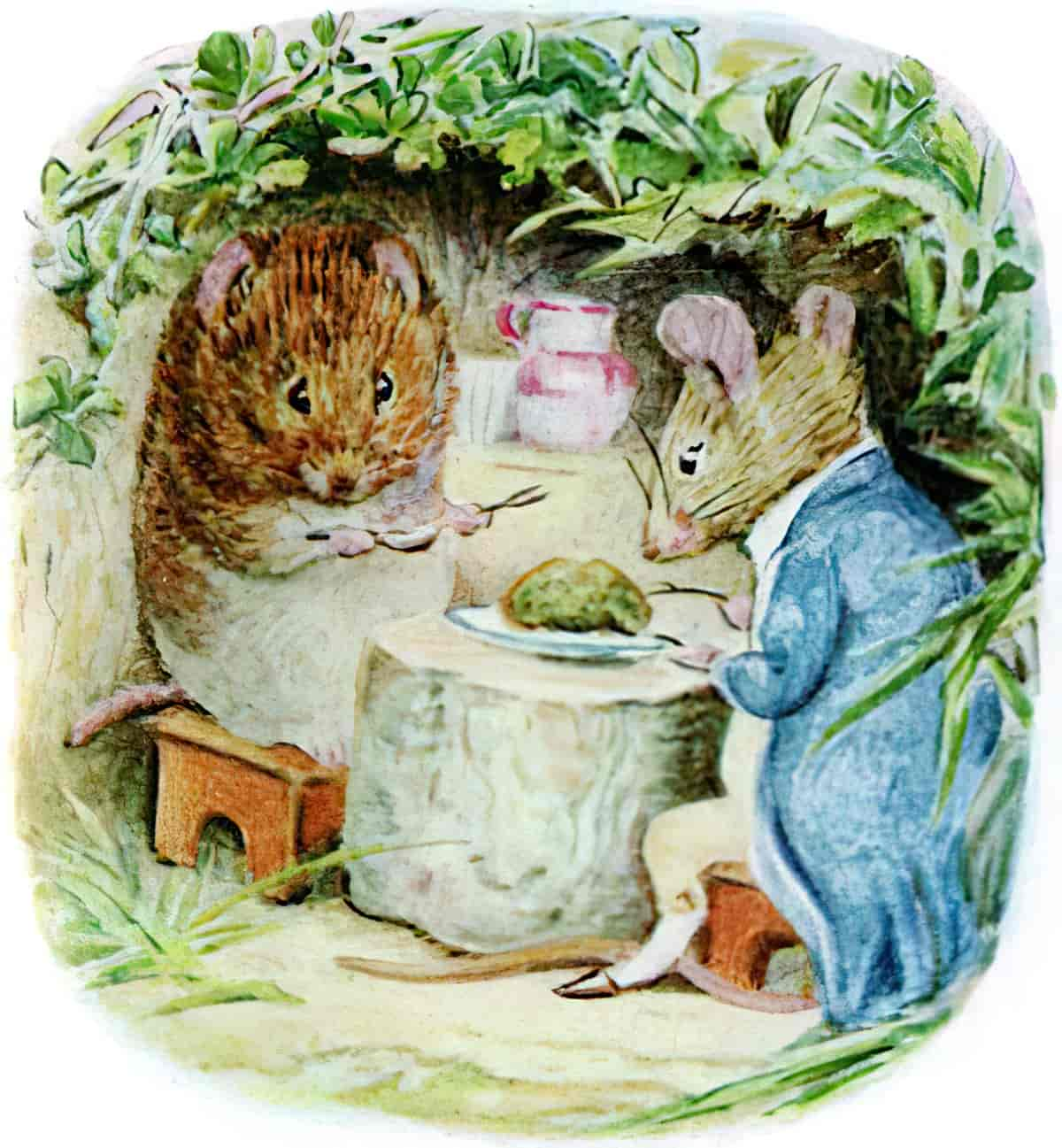

“Why don’t those youngsters come back with the dessert?” It should be explained that two young mice, who were waiting on the others, went skirmishing upstairs to the kitchen between courses. Several times they had come tumbling in, squeaking and laughing; Timmy Willie learnt with horror that they were being chased by the cat. His appetite failed, he felt faint. “Try some jelly?” said Johnny Town-mouse.

Between the mice themselves, there is another sort of Opposition: The stereotypical opposition that occurs between ‘cultured’ and polite city folk when they rub up against the working classes from the country. Timmy is naked, wearing only his fur, whereas the city mice are wearing expensive clothes. In this case, with sympathies so fully lying with Timmy, these expensive clothes are coded as a type of deceptive mask — who do these city mice think they are, dressing up fancy like that? Underneath, we are all just plain old mice.

So are these mice allies, or are they false allies?

PLAN

Timmy’s Plan is to make it back home to the country where he feels safe. The entire story is about that. He is stuck in this big house where everything is supplied, but it might as well be a haunted horror house. Potter makes use of death metaphors, for example the ‘smears of jam’ (blood). Is this a Hotel California situation?

BIG STRUGGLE

Apart from the very real threat of the cat, this is a psychological horror. Timmy is so upset he loses significant weight in just a few days in the big, city house.

ANAGNORISIS

Timmy’s journey back home is surprisingly easy and underwhelming — the hamper goes back to the country weekly. All Timmy needs to do is get back in it. So that’s what he does, resolving the plot.

Potter tacks an extra story onto the end of this one: Seasons change and Timmy gets a visit from Johnny Town-mouse. We learn that the cat has killed the canary inside the house of horrors. So, there was a big big struggle scene after all, but Potter decided to recount it via a hypodiegetic narrator rather than turn it into a horrifying bloodbath of a scene.

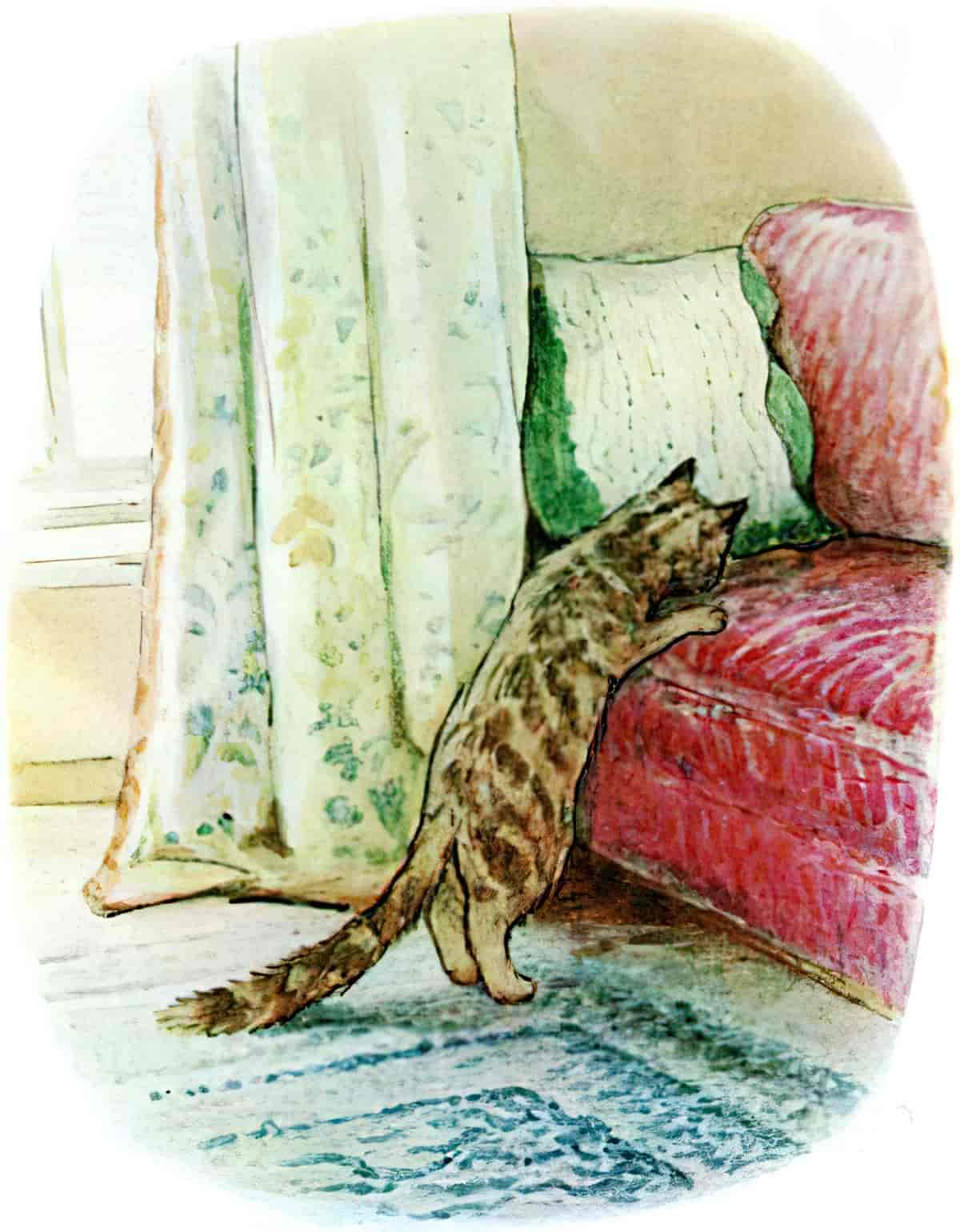

In this illustration there’s no dead canary, but I assume it’s inside the cat’s belly. Cat sits on windowsill, currently digesting, looking godlike upon the chaos while the cook turns her back, oblivious to the animal stories happening all around her.

Johnny finds the country just as noisy and startling as Timmy finds the city, with the cows mooing and the lawnmower engine running.

NEW SITUATION

After his excursion to the country, Johnny Town-mouse finds the country too quiet. (Despite the cows and the lawnmower.) So he returns. Each mouse is happy in his own environment.

The moral of the Aesop fable is as following:

Poverty with security is better than plenty in the midst of fear and uncertainty.

This is a fairly complex message. In bowdlerised versions of this fable, the message tends to get simplified by the younger audience: country life is fun; the city is a child cage. And so it is here. Potter vastly simplifies the message, and offers readers her own personal opinion:

One place suits one person, another place suits another person. For my part I prefer to live in the country, like Timmy Willie.

In case we didn’t pick it up.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Other authors and illustrators have adapted this tale for children.