American writer Carson McCullers published “The Jockey” in 1941, when she was just 24, which seems young, until you realise she’d published “Sucker” at the age of 17 and a novel at age 22.

McCullers belonged to a generation who spent their youth living through world war. Surely that affords a measure of maturity. She had also endured a number of strokes, which were to eventually paralyse one half of her body. She was married by the time she wrote this. Apparently, when her husband forged his signature to get the money she received for this story from the New Yorker, that was the last straw, and she (temporarily) left him. They reunited later, he tried to persuade her to double suicide with him, she refused, and he suicided on his own.

Anyhow, the biographical relevance to this story, as well as to McCullers’ other work, is the pervasive sense of loneliness and loss. The character of the jockey is a lonely figure, and Carson McCullers possibly created him as version of her health-impacted self. McCullers had also endured disappointment in the form of lost potential.. She was set to attend Julliard as she was an accomplished concert pianist, but she lost the tuition money and was required to do menial jobs and write stories instead of attending this prestigious school. Fortunately for us, McCullers was as accomplished at writing as she was at playing piano.

Karen Russell reads Carson McCullers’s “The Jockey” at The New Yorker podcast.

When I first read this story I had little idea what it was meant to be about, so I’m glad to have Russell’s commentary as a kicking off point.

SETTING OF THE JOCKEY

- PERIOD — c. 1940s, August, in an era when horse racing was a significant form of masculine entertainment.

- DURATION — a portion of one dinnertime

- LOCATION — Saratoga. (Being non-American, I only know of this place because of the Carly Simon song “You’re So Vain”.) Another American story set around the horse racing world is “I’m A Fool” by Sherwood Anderson (Sandusky rather than Saratoga).

- ARENA — a dining area. Other short stories with a similar arena, set entirely in an eating establishment: “A Dill Pickle” and “Je ne parle pas Francais” by Katherine Mansfield. Typically, such stories have low concept plots, allowing interpersonal drama to come to the fore.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — I’m reading this in the year of a pandemic, and naturally think of how the rich man so easily sacrifices the health and safety of jockeys for the sake of his own economic gain.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — This story seems to centre on the emotion of humiliation. Humiliation comes in many forms: There’s humiliation which comes at us after a singular moment of shame, and then there’s the enduring humilation and stress of existing at the bottom of a social hierarchy, where you’re treated as a non-human, little care extended to your well-being.

CHARACTERS OF THE JOCKEY

There exist a number of reasons why writers avoid naming, and thereby individuating, characters in a story. In this case, McCullers has decided to work with archetypes rather than unique individuals. Hence: the bookie, the rich man (owner), the trainer. (Technically we do get their names: Simmons, Sylvester and Seltzer — comically alliterative and not designed to allow readers to easily individuate.) Bitsy Barlow is also comically alliterative.

These titles hark back to fairytale archetypes. The rich man is the fairytale king. The jockey is the youngest brother who we are meant to root for. The others are men who achieve their power by association with the king.

Cullers makes a social observation by describing the owner’s clothing compared to that of the jockey:

The rich man shifted his position, turning sidewise in his chair and crossing his legs. He was dressed in twill riding pants, unpolished boots, and a shabby brown jacket — this was his outfit day and night in the racing season, although he was never seen on a horse.

Poor people bankrupt themselves to give the appearance of riches while actual rich people doing their darnedest to appear as if they are members of the working class. Annie Proulx makes this same observation in her short stories. In “The Blood Bay“, a character foolishly puts all his money into buying a pair of boots. In another story, “Man Crawling Out Of Trees“, a man who does actually have money moves to Wyoming and immediately buys new clothes (and a new wagon) in order to disguise himself as a working class local.

In fairytale, rich clothes equal rich people. You won’t find rich people deliberately dressing down in fairytales. However, a “Puss In Boots” plot shows that poor characters are able to deceive by dressing up.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE JOCKEY

SHORTCOMING

Whose story is this? Perhaps the clue’s in the title. Also, the narrative opens with focus on Bitsy, the jockey, and the reader is thereby likely to empathise with him. (Readers are like ducklings.)

Bitsy is a clear underdog, emphasised by his name, which seems connected to his size: He is a ‘bit’ of a man. With size so linked to masculinity in our culture, his small stature automatically removes him from that whole hierarchy. He never got a look-in, and instead took the the one clear route open to him as a very small man: the job of a jockey.

DESIRE

The jockey is bursting with a simmering rage about the treatment of jockeys in the horse racing industry, which make a few men rich, but not the men who risk life and limb. He may be partly manufacturing the opportunity to give the men who control him an earful.

At a deeper level, I suspect he’s sick and tired of patriarchy and capitalism, though whether he has thought things through to that extent and able to put labels on them is a completely different matter. For now, he’s angry at these men, who represent both of those things.

OPPONENT

The bookie believes the jockey is ‘crazy’. Interestingly, this is a common way of writing off women, who were regularly deemed ‘hysterical’ (code word for ‘crazy’, code word for ‘her problems aren’t worth listening to.)

Like many women of this era, the jockey is relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy. A useful jockey is the size of a small adult woman, so I believe he is experiencing some of what a woman faces, especially in the 1940s. Perhaps McCullers was able to write the character of the jockey because she moved through the world as a femme coded person whose self-image didn’t match perfectly with the person others saw.

Unlike women, however, this jockey doesn’t have the advantage of a wide network of other women who understand him at an intuitive level. Cue: loneliness.

We don’t actually know what motivates the jockey in this story because, as Karen Russell points out in her New Yorker commentary, interiority is entirely absent. Add this to the list of how this story is a mid 20th century fairytales. Fairytales also lack interiority of any kind.

PLAN

Is the jockey eye-balling the men at the table hoping to catch their eye, get an invite and then give them a piece of his mind?

The jockey waited with his back to the wall and scrutinized the room with pinched, crêpy eyes. He examined the room until at last his eyes reached a table in a corner diagonally across from him, at which three men were sitting.

In this I’m reminded of a film by the same guy who wrote Love, Actually, Richard Curtis. I can’t stand Love, Actually, but made-for-TV movie The Girl In The Café (2005) impressed me a lot. In that story, a young woman gets the opportunity to attend a conference with very important political decision makers and takes the opportunity to go against social convention and stand up for what she believes is right.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Typically in a masculine mythic narrative, the conflict builds until it reaches a crescendo, a.k.a. the climax. This story seems to deliberately subvert this crescendo followed by deflation, which audiences typically find so satisfying.

But there is no satisfaction here. In that, the reader experiences what the jockey experiences: frustration.

Instead, the story goes like this: Jockey stands nearby, jockey is invited to the ‘adults’ table’, jockey conveys dissatisfaction at the entire exploitative system in which a fellow jockey and friend is severely injured and now walks with one leg two inches shorter than the other. Jockey is treated like a boy, warned against drinking. Jockey goes to the bar, partly to prove his adult autonomy, the men talk about jockey behind jockey’s back, jockey returns to table and calls the men Libertines.

There’s no ‘big moment’. McCullers has favoured realism over satisfying build and climax.

ANAGNORISIS

None of the characters seem to learn anything about themselves or about life. The jockey is already pretty aware of how the hierarchy works at the story’s beginning. The other men are too comfortable in their places within the system to take the jockey seriously. It’s far easier to simply write him off as crazy. Then they don’t have to confront the exploitative aspect of their business.

Perhaps McCullers’ contemporary readers needed to be reminded of that. If a character arc happens here, it’s only on the part of the reader.

NEW SITUATION

Since the rich man, the bookie and the trainer learn nothing, and since they control how the horse racing game works, I doubt anything will change for the better.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

If anything, the jockey’s life may get worse.

RESONANCE

Here in Australia, the big, national horse race known as The Melbourne Cup is coming under increasing attention for its maltreatment of horses. Any struggles in that particular human hierarchy get far less attention. Culturally, we are more aware of animal abuse today than we were in the 1940s, so this makes sense.

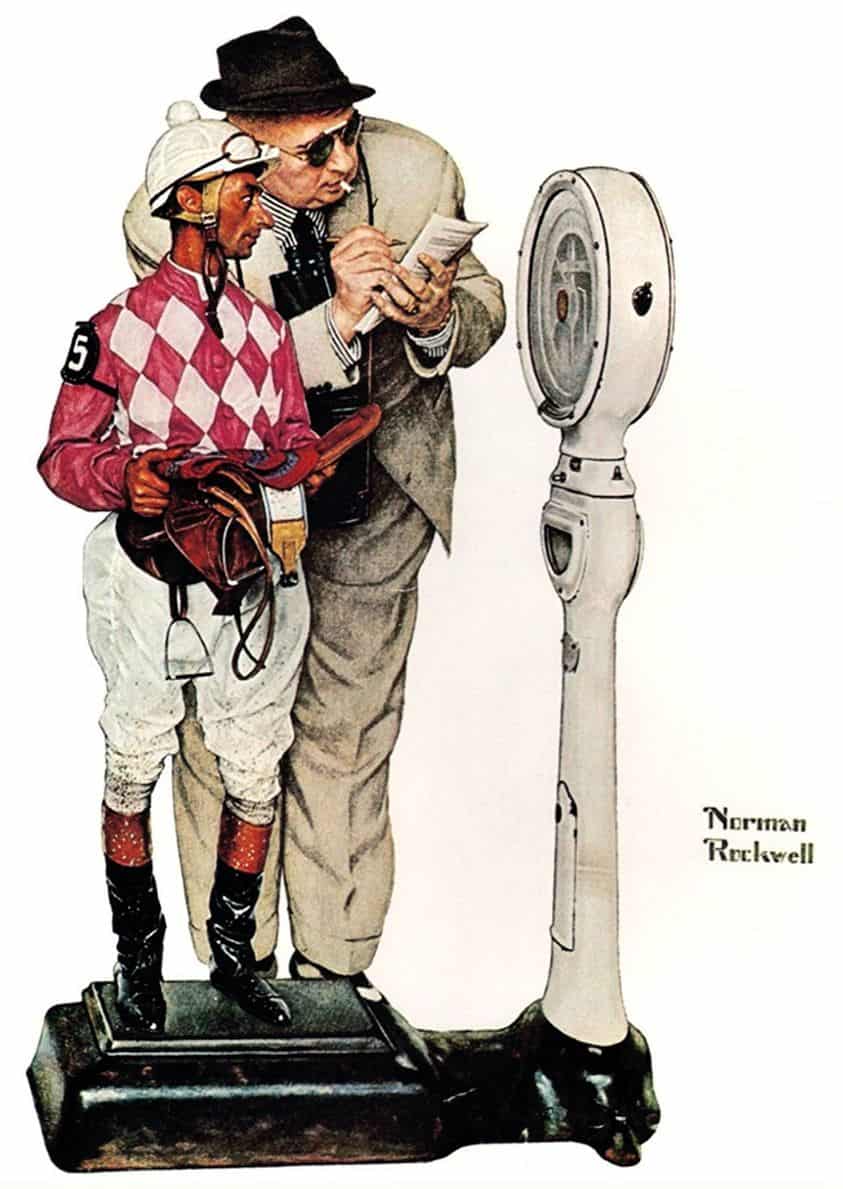

Header illustration: for the Saturday Evening Post Jockey Weighing In, cover by Norman Rockwell, June 28, 1958. Jockey Eddie Arcaro, then at the peak of his career, was profiled in the issue. Rockwell painted two versions, one in which the jockey’s britches are spotless, the other where they are spattered with mud.