“Je ne parle pas français” (I don’t speak French) is a 1918 short story by Katherine Mansfield. Nothing much ‘happens’, but the character of Raoul Duquette is a comedic archetype seen in contemporary creations such as Dwight Schrute from The Office.

Connection To Mansfield’s Own Life

Hard to fathom today, but the obliquely gay subject matter of this story would have shocked a 1918 readership. John Middleton Murry therefore printed it privately. When it was published for a wider audience in 1920, it was only after heavy censoring. Mansfield hated the cuts, which amounted to bowdlerisation.

THE BOWDLERISATION OF Lgbtq TEXTS

Bowdlerisation is the act of editing a work in an attempt to make it ‘more suitable’ for its intended audience. The word often used to describe adult literary works subsequently adapted for a young reader.

But bowdlerisation can be carried out for other, political reasons. For instance, a lesbian love story might be bowdlerised by removing the lesbian elements, gender flipping it, avoiding the obvious, or by cherchez l’homme (tracing any woman’s motivations back to her supposed desire for a man). Emily Dickinson’s letters to Sue Gilbert were bowdlerised by Dickinson’s niece, Martha, who deleted sentences such as ‘be my own again, and kiss me as you used to’. Note that Martha published her famous aunt’s bowdlerised love letters in 1920 — the exact year “Je ne parle pas francais” was released to the public.

Katherine Mansfield’s private letters have been subjected to these strategies, along with Frances Hodgkins, Ursula Bethell and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Owing to the obliqueness required by the era, this short story has been interpreted in different ways by various commentators:

- a reflection on the impact mass media has on reality, or how people decode reality. (Mass media was nascent at the time, so Mansfield demonstrates quite some insight into the impact it would eventually have on us all moving forward.)

- a story about the menace of pretence. Power without value can be attractive and value without power can be debilitating.

- a bemused exploration of pop genres e.g. the sensational vs the sentimental

Some commentators have suggested that Katherine Mansfield would have identified in turn with Duquette and with Mouse. Like Duquette, Mansfield was a theatre creative, liked to hang out in cafes observing humanity and was a member of the rainbow community (bisexual? pansexual?). And she had certainly experienced the emotions we might expect Mouse to experience in this story, alone in another country where she doesn’t speak the language, disconnected from everything she knows to be home.

By the way, Mansfield did speak French. She would speak schoolgirl French with her sisters, thinking no one else in their company could understand what they were saying. (Others very often could — French has been studied by academic streams in New Zealand high schools for generations.) If you don’t speak French: This is how to pronounce the title.

What happens in “Je ne parle pas français”?

Given the choice between trivial material brilliantly told versus profound material badly told, an audience will always choose the trivial told brilliantly.

Robert McKee, Story

This is not a high concept log line: A man sits in a French cafe, musing about the time he met Mouse, the nickname of a love opponent. The story is revealed to us slowly, and we the narrator’s background, dovetailing his setting present with past events. Meanwhile, we are expected to read behind the lines. As the past dovetails with the present, the reality of Duquette’s desires/plans bifurcates from the story he’s telling us.

So what’s between the lines? Duquette has fallen in love (or lust) with an Englishman named Dick. They hang around together but then Dick returns to England, shocking Duquette by dismissing the close relationship Duquette thinks they’ve shared. But Dick returns to Paris later, this time bringing a woman with him. Dick does not know what to make of this. Is she a cover or is she his lover? Duquette is ultimately unable to code Dick as a straight guy and invents a narrative in which Dick flees his girlfriend, unable to pursue a romantic relationship with either a man or a woman, returning instead to his mother.

Stories in which a character sits around and observes are difficult to pull off. The longer the story, the harder it is to pull off, and I think these stories are much better suited to the short story form than to the novel. Today readers have less patience for the flaneur, which basically describes Duquette. Standing around in a cafe is inherently boring, so any ‘action’ in a story like this derives from the backstory. The cafe scene bookends the love tragedy of Dick and Duquette, and offers readers an insight into Duquette’s character, showing us that he is not reliable. When he offers commentary on the cafe and its characters, he’s telling us far more about himself.

Narration

“Je ne parle pas français” is an excellent example of ‘unreliable narration’. Via the technique of internal monologue, more is revealed of the viewpoint character than the character understands about himself. Raoul Duquette is a comedic character lacking in self-awareness, though I believe he’s keeping details to himself for safety reasons. (It was not safe being rainbow in early 1900s Europe.)

Whenever Mansfield made use of irony it was narrative irony. She created a gap between what the reader understands and what the viewpoint characters understand. This narrative irony is one way of creating dramatic irony. Mansfield made use of it right from her earliest work — “In A Cafe” uses the same form of narrative irony and was written at the age of 19.

Mansfield had already created unreliable narrators in the earlier German Pension stories. But Raoul Duquette is more subtle and complex than the young, naive Englishwoman who narrated those. By the time she wrote “Je ne parle pas français” Mansfield had mastered the technique of narrative irony.

Mansfield wrote in first person more often in her earlier, less sophisticated stories. Her best work tends to be third person. This is her most sophisticated story written in first person.

SETTING OF “JE NE PARLE PAS FRANCAIS”

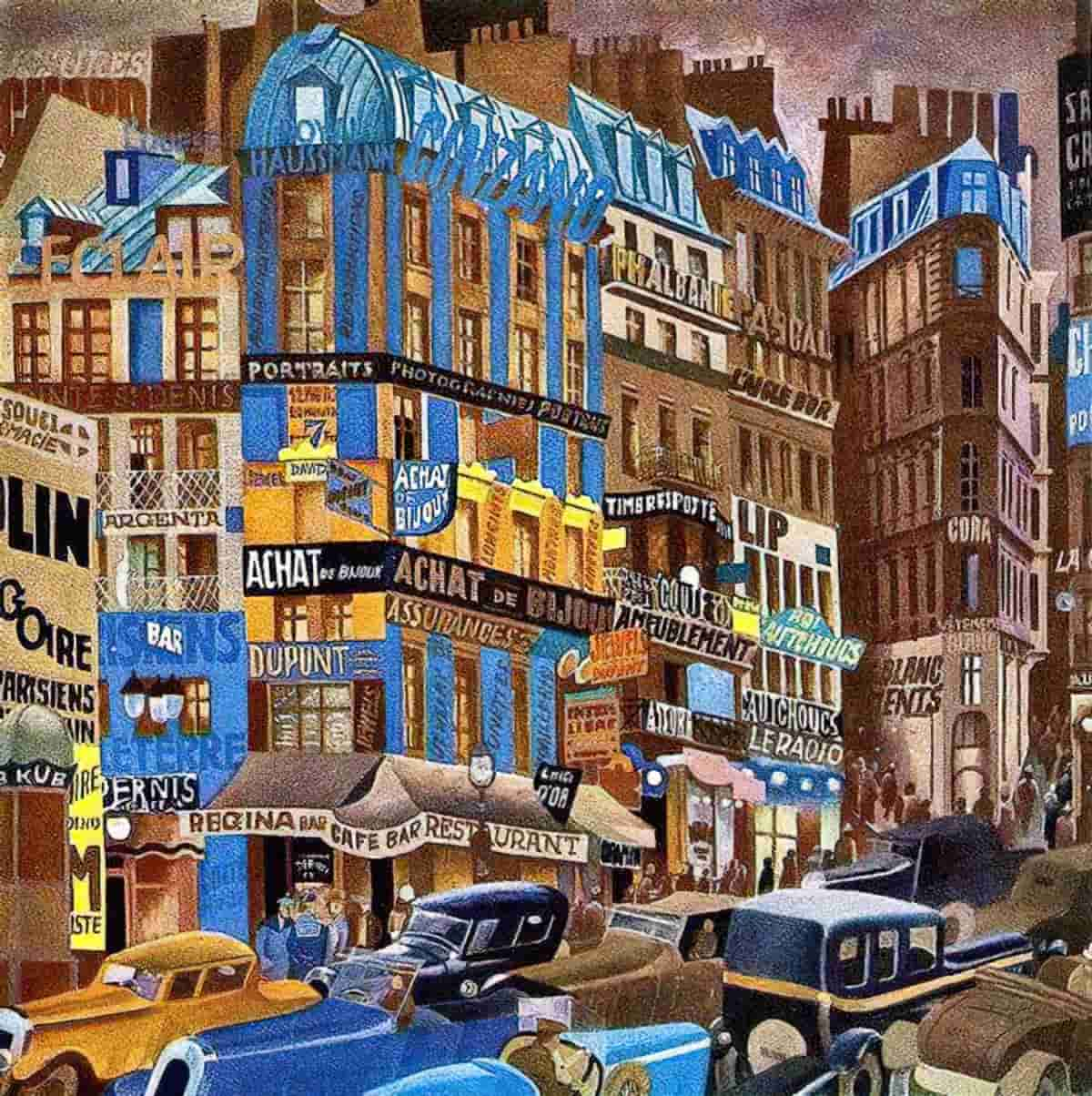

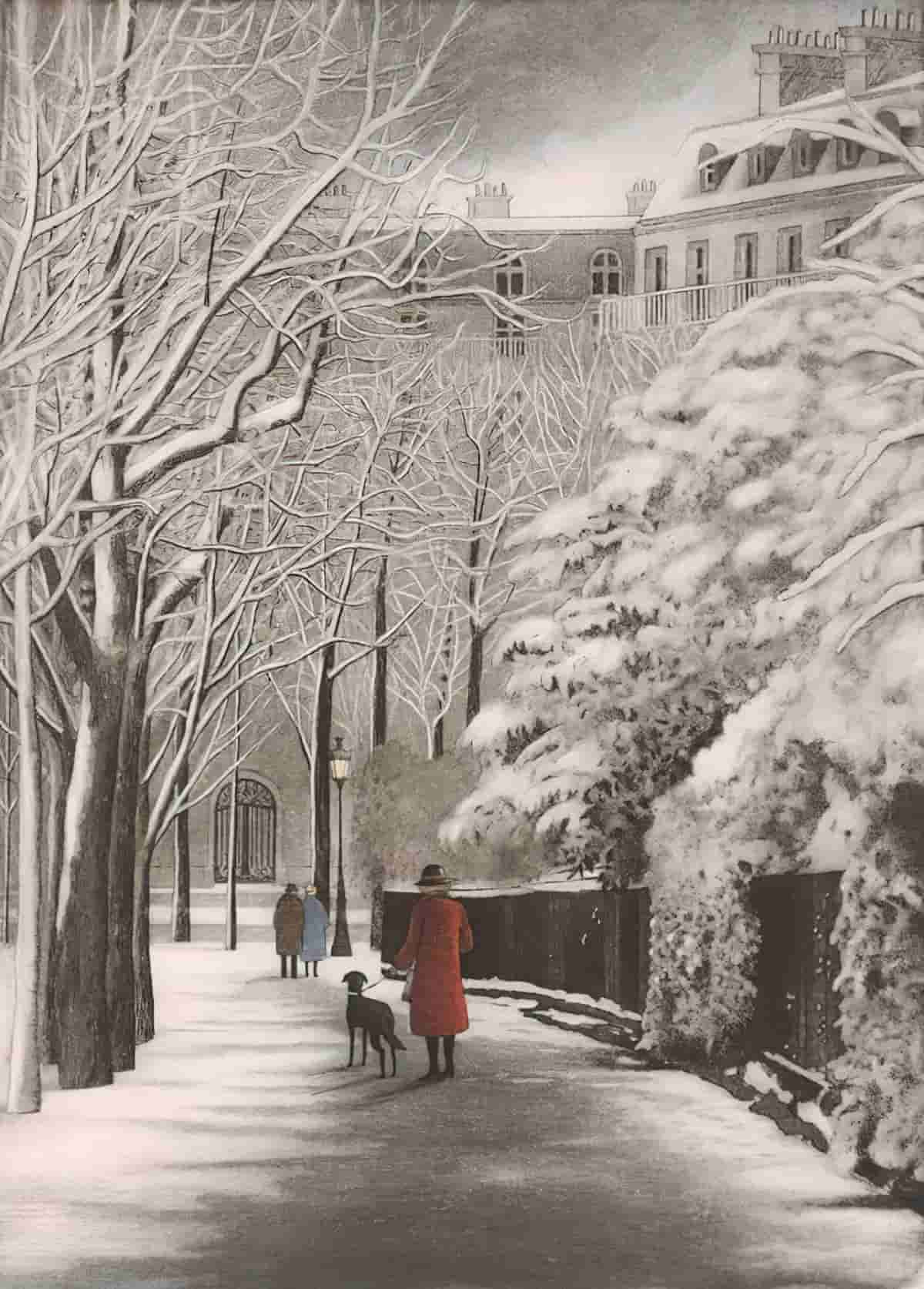

The bookend setting of the seedy Parisian cafe juxtaposes ironically with the meat of the story — the imaginatively romantic melodrama of Duquette and Dick’s love life.

There is also juxtaposition in the public/private spaces. The cafe is a degraded public space whereas the meat of the story takes place in private. (The secret story happens entirely off the page.)

This story is all about the public/private/secret divisions which segment our lives. If you’re writing a story with this division at its heart, think about how your settings might underscore the theme.

Was Mansfield a country mouse or a city mouse? In “Vignettes“, city life is seen as liberating. But in the later “Je ne parle pas français”, city life is seen as sophisticated in a corrupt sort of way. Ina daydream, Duquette pictures himself and Mouse living a simple life away from the city.

Mansfield’s feelings about the city had clearly changed in the 10 years between those two stories.

What was happening in Paris around 1918-1920? World War I was over and people weren’t expecting another one in their lifetimes. Overall, this was a time of hope and jubilation. Paris celebrated the win with a big parade. Food rationing had ended. The demolition of the Theirs Wall began in 1919. This had been built around the city in the 1840s. The fortification would gradually be replaced with low-cost housing. In 1921, the Paris population reached its historic high. The city’s economy boomed until the effects of the Great Depression hit 10 years later, in 1931. Katherine Mansfield didn’t live to see the Depression. She died in 1923.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “JE NE PARLE PAS FRANCAIS”

SHORTCOMING

What are we encouraged to feel about Raoul Duquette?

He is drawn to melodrama.

He wins us over with a mixture of flamboyant cynicism, faux-self awareness and cutting observations.

Yet he has delusions of grandeur, considering himself the demiurge of his own paracosm (which he doesn’t realise is a paracosm, conflating his construction of reality with veridical truth).

Duquette habitually creates roles for himself and others. We must mindfully sit on the fence about Dick (and about Mouse). We never meet Dick except via the erotically motivated Duquette, so Dick could be anyone at all. We can’t trust Duquette to describe him.

IMAGINARY AUDIENCE

Today we might casually diagnose Duquette with narcissism, though I prefer to think in terms of ‘imaginary audience’, which is much more common, and perhaps a feature of youth in general.

The imaginary audience refers to a state where an individual imagines and believes that multitudes of people are enthusiastically listening to or watching him or her. Though this state is often exhibited in young adolescence, people of any age may harbour a fantasy of animaginary audience.

Wikipedia, Imaginary Audience

Extended Metaphor OF THE STAGE

For Duquette, life is a stage. This creates a microcosm in which the drama plays: the play within a play, involving Mouse and Dick Harmon.

“Je ne parle pas français” uses language in order to expose language, constructs a form (the recalled memory, which shapes the whole story as an extended “as if”) that will also function metaphorically — as an embodiment, here, of the menace of pretence. To recognize that power without value can be attractive and that value without power can be debilitating is, in other words, a concrete challenge to language as well as an abstract problem in morality. And “Je ne parle pas français” is not alone in probing this issue. The value of language is one of the most pervasive motifs in Mansfield’s writing, and questioning the consequences of language can be one of the most unsettling results of examining her formal practice.

Reading Mansfield and Metaphors of Form by William Herbert New

The stage metaphor in turn leads us to a deeper theme regarding the two lives we lead — the life of performance and artifice vs the authentic life. Japanese culture has everyday words to describe these two selves — omote and ura, ‘face’ and ‘mind’ (in old Japanese). English lacks vocabulary to describe this dichotomy, except in academic circles.

SOLIPSISM

Solipsism: the view or theory that the self is all that can be known to exist. You feel like other people are just robots, or automatons, or something like that. Your feelings are real, but theirs are not.

I would use the word ‘solipsistic’ to describe Duquette. He doesn’t believe in a human soul. He walks into the cafe as if he is the only real human. Everyone else is a prop. When he thinks of others, he casts them in stories. First the straw floor of the cafe reminds him of the nativity scene, then he refers to Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night with the phrase “dying fall”. In the first scene of Twelfth Night a lovesick count named Orsino is listening to music that has a “dying fall.” Today musicians might use the phrase to describe a diminuendo or decrescendo. This dying fall foreshadows the melodramatic ‘swan song’ mentioned later in the story. Like the story of the swan who sings beautifully before keeling over, dead, Duquette is comically melodramatic, and the stand-out unexpected detail from this story is the line about the dead kitten:

No paper or envelopes, of course. Only a morsel of pink blotting-paper, incredibly soft and limp and almost moist, like the tongue of a little dead kitten, which I’ve never felt.

The structure of the bit reminds me of the line: “A theologian is like a blind man in a dark room searching for a black cat… which isn’t there.”

DUQUETTE, DWIGHT & HUMOUR

But of all the contemporary characters that spring to mind, Duquette reminds me (at a non-surface level) of Dwight Schrute from The Office (American spin-off). Both characters ‘save time’ when asking questions. The following is from Mansfield’s story:

Query : Why am I so bitter against Life ? And why do I see her as a rag-picker on the American cinema, shuffling along wrapped in a filthy shawl with her old claws crooked over a stick ?

Answer: The direct result of the American cinema acting upon a weak mind.

Dwight Schrute also says, “Question” before asking questions. Though Dwight is a hopelessly naive lover of high fantasy, I imagine he might feel similarly dismissive of cinema. Like the comedic character of Duquette (and also Walter Mitty), Dwight Schrute fancies himself the central character of his own private narrative. In Dwight’s case this manifests in him coming to the rescue of people who don’t need saving, but all in the aid of proving his own worth, mainly to himself.

Duquette saves no one and he knows it, but the similarities continue. Like Duquette, Dwight Schrute has little affection for cats. (Dwight puts Angela’s beloved cat in her freezer, which ends their romance.) A dead cat to Dwight is the same as an alive one. Both characters are melodramatic but without the sentimentality you might expect to go with. But as you read, notice how Duquette makes a show of sentimentality. He’s not genuinely sentimental, in my opinion. Some commentators have dismissed Mansfield for writing cloying, twee little stories but those commentators have failed to grasp the subtle irony.

Duquette and Dwight’s lack of sentimentality derives from self-absorption. Though this is also Duquette’s line, I can imagine Dwight Schrute saying, “I have no patience with people who can’t let go of things, who will follow after and cry out. When a thing’s gone, it’s gone. It’s over and done with. Let it go, then! Ignore it, and comfort yourself, if you do want comforting, with the thought that you never do recover the same thing that you lose. It’s always a new thing. The moment it leaves you it’s changed.” This philosophical stance foreshadows the end of Mansfield’s story: There will be no Anagnorisis for the character, in true Literary Impressionist style. (The literary Impressionists thought Anagnorisiss were contrivances, since people don’t easily change.)

Like Dwight (and also Michael Scott, his boss), we laugh at Duquette because his comparisons run to the absurd, even if the beginning of a paragraph makes superficial sense: “Why, that’s even true of a hat you chase after”, Duquette continues, “and I don’t mean superficially—I mean profoundly speaking…”

Humour derives from the bafflement of the reader, discombobulated owing to the lack of apparent segue. (Another comedy series that takes The Ridiculous Comparison to its extreme is Welcome To Night Vale.) https://youtu.be/GU2W_nlijx0

I don’t want to make too much of the Dwight Schrute/Raoul Duquette comparison. On the surface they are unalike. After all, Duquette is a Frenchman and a dandy living in the early 1900s. Schrute is an Amish-background contemporary American office worker who farms beets and plays competitive ping pong.

But to conclude to topic of Duquette’s Shortcomings, the extent of Duquette’s moral shortcoming is kept as a humorously conveyed reveal for the end of the story. He has the ability to not care too much about the welfare of others.

DESIRE

Duquette wants to be a part of something big. Not only that, he wants to be at the centre of it. He wants the attention of others. This is connected to his needs and shortcomings — these two aspects are inextricable in the best stories.

Clearly, he also wants love. Or sex. We don’t know because he’s not letting on. Maybe just the latter.

PSYCHO-SEXUAL VAMPIRISM

There’s a trope known as the ‘psycho-sexual vampire’. Raoul Duquette is a good example, being a voyeur who ‘feeds’ on the emotions of others. Moreover, he wants to manipulate the reader by taking us into his confidence (ostensibly) and creates complicity. Unless we step back and say, “Hang on, is this guy telling me the truth of the situation?” we’re likely to be fully taken in, Lolita style.

Psycho sexual stories are about the psychological aspects of sex. A Nazi sympathiser was one of the first writers to create the vampire as a symbol of the psycho sexual impulse. His name was Hanns Heinz Ewers. Partly for the Nazi reason, his work isn’t very popular today. Check out Alraune (1911) if you’d like to go there.

But let’s go back a little earlier, to a work ahead of its time. Carmilla is a gothic novella written by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, published 1871-2. The plot of this older story revolves around a beautiful female vampire’s attempts to seduce a frail young girl. It’s a rare lesbian love story. In fact, the vampire part only comes in at the end, when Laura realises ‘Carmilla’, who has been trying to seduce her, is in fact succubus type creature and must be killed. The psychological complexity of this vampire story is what makes Le Fanu’s story ahead of its time.

“Je ne parle pas français” is not a supernatural horror at all, but Raoul Duquette shares commonalities with the horror vampire of the age. I would love to know if Mansfield read Carmilla. There’s a good chance she did, being well-read, being in love with women, and with Carmilla being the stand-out vampire story of the age until Bram Stoker’s Dracula. (The sexual aspects of Carmilla in turn influenced Dracula.)

But historically there are very few gay vampire stories featuring two male characters. I wonder if Mansfield saw a gap that needed filling, inspired by Le Fanu’s work. There’s nothing supernatural about “Je ne parle pas français” — supernatural wasn’t Mansfield’s thing. But remember, Le Fanu’s story didn’t have much supernatural about it either, despite the vampire. In Carmilla, as in Mansfield’s story, we have one character who is in touch with her sexuality (Carmilla/Duquette) while the other pulls away (Laura/Dick). This oscillation between attraction and repulsion drives the Erotics of Abstinence audiences continue to enjoy today in stories such as Twilight.

OPPONENT

Duquette’s romantic opponent is Dick, who may or may not have a handle on his own sexual orientation, who may or may not be into men, and the situation becomes triangulated with the arrival of (female) Mouse.

Duquette doesn’t really acknowledge at any point that Mouse is his opponent. He doesn’t seem to know why he didn’t help her out. Instead he considers ‘Life Itself’ his opponent, an ‘old hag’, because life doesn’t abide by confirming Duquette’s own view of himself. (Except very occasionally, like when he walked into this cafe today and felt he was at the centre of something big.)

PLAN

Like any gay man in an era when sexually transgressive acts are illegal, Duquette dissembles by avoiding a direct declaration of his desires, let alone exactly how he will get what he wants. At the turn of the century, ‘homosexuality’ was only just beginning to be conceptualised as an identity rather than simply an (illegal) act. But he clearly figures if he and Dick only spend enough time together than their relationship would naturally progress… somehow.

“After that I took Dick about with me everywhere, and he came to my flat, and sat in the arm-chair, very indolent, playing with the paper-knife. I cannot think why his indolence always gave me the impression he had been to sea … I sometimes wondered if he wasn’t completely innocent.”

In the early 1900s, one’s sex life was a private matter. Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy (in her 1996 essay “But we would never talk about it’: The Structures of Lesbian Discretion in South Dakota, 1928-1933”) has said, in regards to determining individuals’ biographies, that if people seemed to deny their orientation in earlier eras, this ‘should be interpreted as an assertion that their sexuality was not a public matter, rather than as a denial that they have a sexual interest in [the same sex]’.

gay language

I would be interested to know if ‘has been to sea’ is a euphemism of early 1900s Gay Polari. Are there contemporary examples in pop culture, for instance from the song “Beautiful Boys” by CocoRosie about Jean Genet, ‘tattoos of ships and tattoos of tears‘. Across time, the navy and ships are connected to gay culture. https://youtu.be/Y3p4e-htTHw

Gay love on ships goes back way further than The Village People — matelotage was a gay marriage of sorts practiced by male pirates from the 17th century. Pirates were themselves transgressive, so it shouldn’t be all that surprising that they had a higher tolerance for other transgressive ways of living.

The phrase ‘Parisian, a true Parisian’ is almost certainly code for a gay man, with associations of a gigolo of duplicitous nature and the kind of effete man with literary pretensions. (Historically, marginalised groups required to wear public masks for their own safety have also been simultaneously persecuted for ‘lying’ about themselves.)

BIG STRUGGLE

Dick flees from his woman companion and runs back to his mother from Paris, unable to face getting into a relationship with Mouse, or perhaps with any woman. In Duquette’s head this has been a Romeo and Juliet-esque suicide with all the imagined melodrama around that.

The story that takes place inside Dick’s head shows that the character is playing into a narrative — and cultural phenomenon — which began in the 1800s and which continues dangerously into the present:

As gay identity spread, so did the notion that gay men were more prone to suicide. Late-19th- and early 20th-century writers picked up on the association between homosexuality and suicide … when gay characters’ deaths are portrayed lovingly, romantically or cathartically today – such as the suicide of Virginia Woolf in the novel The Hours (1998) or of Michael Corrigan in the TV drama House of Cards (2013-15) – it is worth noting these are echoes of a literary device that first sounded in Weimar Berlin. And to acknowledge that, so long as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) teenagers see characters who look and talk and think like themselves, and who then kill themselves, suicide will continue to suggest itself as a plausible course of action.

Sam Haselby, Aeon

Of course, we don’t know Dick is gay and he does not in fact die in the story. He simply goes home to England, using his mother as an excuse to end the relationship with Mouse, whatever that entailed. But this dominant cultural narrative is why Duquette has jumped to the suicide conclusion, and why Mansfield would have used it.

Herein lies a downside of internal monologue, in which there’s no unseen narrator to moderate a flawed character’s problematic ideologies: When Mansfield creates the gay-suicide scene she inevitably creates yet another narrative in which a gay man hates himself and dies as a result. With internal monologue (and similar narrative techniques e.g. stream of consciousness) writers are always hoping for the best of readers.

ANAGNORISIS

There is no room for epiphany in this circular text, whose protagonist is condemned to sterile repetition of cultural cliches.

Maurizio Ascari

By the time we reunite with present-world Duquette, still in the cafe, has he experienced any epiphany owing to his association with Dick and Mouse? Any increase at all in his self-awareness? Well no — he may have developed as a human being had he done something self-sacrificial such as look after an English woman alone in Paris — a woman he considers his love opponent and therefore unworthy of his time.

But he doesn’t help her at all, breaking his promise to her. (He didn’t have to promise in the first place — it only made him look good in the moment.) After a double carriage return Mansfield writes with a brilliant touch of humour: “Of course you know what to expect. You anticipate, fully, what I am going to write. It wouldn’t be me, otherwise.” Mansfield has trusted us to understand this character over the course of the story. Duquette is not only an unreliable narrator and an unreliable person in general. Looking back we do see all the clues.

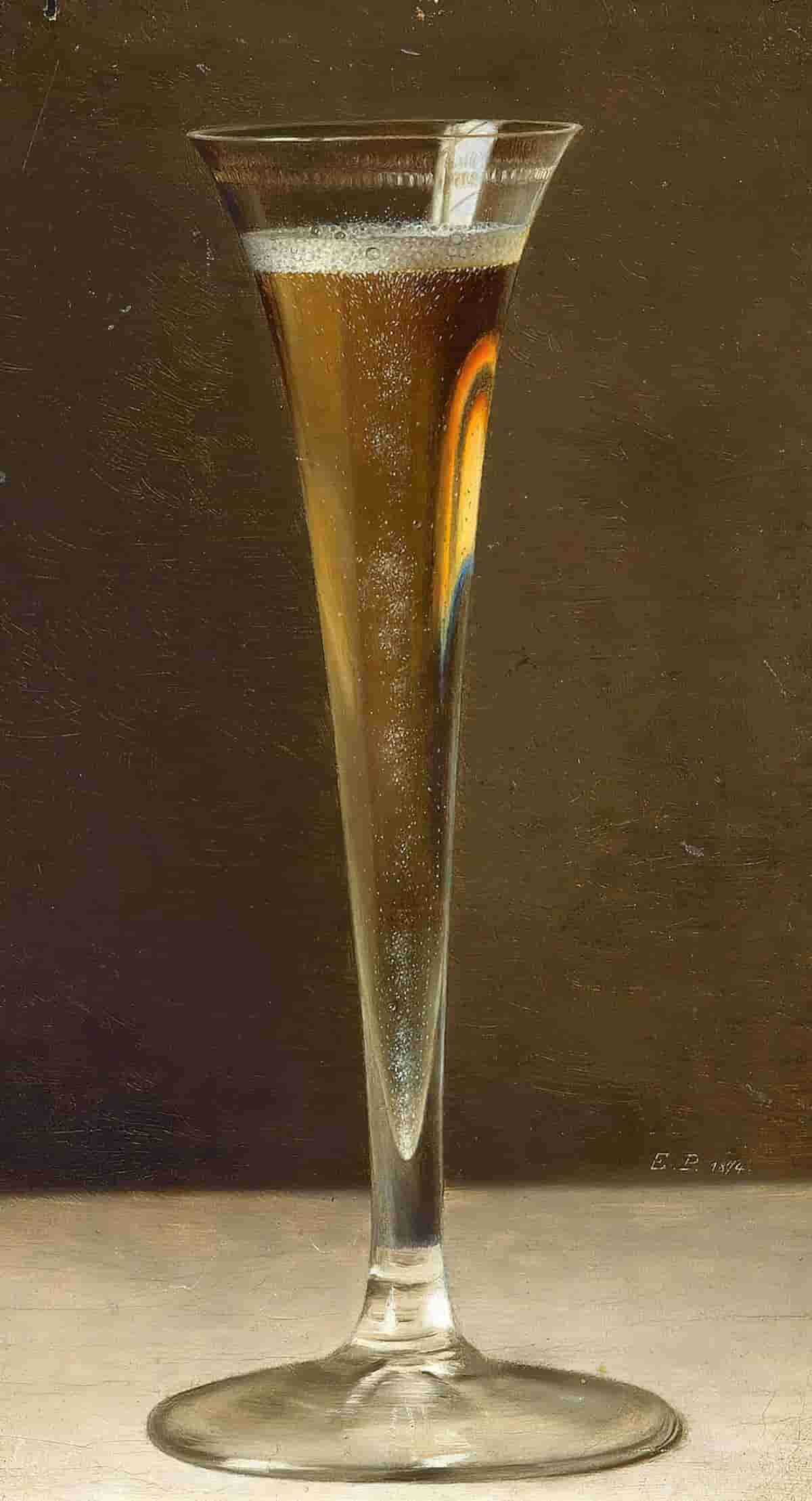

Clues create the symbol web. For instance, Duquette hasn’t paid for either of the mirrors in his house. Mansfield makes much use of mirrors (and windows) in her stories. If Duquette hasn’t paid for the mirrors in his own house, he clearly has little purchase on who he is as a person. There’s nothing subtle about this message: Reader, you can’t trust the guy reflected in these (unpaid for) mirrors. Why does Duquette even tell the reader he hasn’t paid for them? My read is that he’s secretly proud of his ability to get by in life on the smell of an oily rag, living a champagne lifestyle on beer money.

Duquette is probably a working class boy who, through wit and positioning, is hoping to insert himself less precariously into the upper-middle class. In this respect I’m reminded of Miss Delysia La Fosse from Miss Pettigrew Lives For A Day. Delysia is a woman who has married into money, but her impoverished background is kept as a late reveal. The pretty young woman who marries into royalty by behaving in appropriate ways and looking nice in upper-class garb is an archetype as old as myth and fairytales. Duquette will have read them, I suspect.

NEW SITUATION

Duquette still thinks of Mouse whenever he hears certain tunes playing in cafes. But he has already told us he doesn’t live with regret. This feels like a contemporary response. Had he lived in the year 2012 he might be preaching, “YOLO!”

Let’s not gloss past that attitude uncritically. For what is a life sans regret? Regret is a necessary precursor to self-reflection. If we subscribe to an ‘You Only Life Once’ philosophy, we’re in danger of becoming a self-centred population of Raoul Duquettes.

Header painting: Leonid Pasternak Boris Pasternak, Writing, 1919