“Louisa, Please Come Home” is a short story by Shirley Jackson, first published in Ladies Home Journal, 1960.

It’s always the hypothetical children we must save. Not the actual ones.

@Manigarm on Twitter

WHAT HAPPENS IN “LOUISA, PLEASE COME HOME?”

On the face of it, the premise of this short story is pretty far from realism.

19-year-old symbolically named Louisa Tether runs away from her family the day before her sister’s wedding. We’re not told why. General dissatisfaction?

She doesn’t go far. But her family never find her. Every year, her mother pleads on the radio for her daughter to return home.

Eventually a man from Louisa’s old life recognises her. Louisa returns home after all.

But the mother’s response is entirely unexpected: Louisa’s mother doesn’t believe that Louisa is really her daughter. She turns the real Louisa away.

A REAL LIFE CHANGELING STORY

A great plot but implausible, right? Maybe not. The film Changeling is loosely based on a true story which is even more bizarre than Shirley Jackson’s “Louisa, Please Come Home,” and even more bizarre than the movie, in my opinion.

CHRISTINE COLLINS AND HER CHANGELING SON

In the true and harrowing story of child serial murder, a nine-year-old son is kidnapped in 1928 Los Angeles. His mother, Christine Collins, pleads with the police to find him. But the Los Angeles police force is corrupt, misogynistic and all varieties of evil. In order to close off the case, the L.A. Police simply give the mother a different boy, who they know is not her son at all. They gaslight her into almost believing he is hers, only a bit different after a five month absence. When she pleads with them to keep working on the case, they have her locked up in a psychiatric facility. Meanwhile, the real son has been murdered by a young man from Saskatchewan, who first kidnapped his own 13-year old-nephew, abused him, and forced him to contribute to the kidnapping and murders of other boys.

INTO THE MIND OF AN EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY MAN

In popular storytelling by now, sadism and psychopathy are run of the mill. The most unfathomable part of this true story is not the activity of the perpetrator. For me, it’s the actions of the police officer, who gave a distraught and grieving mother a different boy — a 12-year-old runaway from Iowa — and told her to make do. When she complained, the police officer instructed her to take the random kid home to give mothering a go. When she tried to give the boy back, he accused her of being an unfit and irresponsible parent.

Clint Eastwood’s film focuses on the gaslighting by the police department, Christine Collins’ fight to be taken seriously, and then touches upon the legal battle which changed Los Angeles law for the better. (After this case, police were no longer allowed to simply commit civilians to psychiatric institutions if they found them a bit of a nuisance.)

It would be difficult to craft a story which allows audiences proper insight into the mind of the police officer. He thought it acceptable to send a different boy home with a mother who has lost her own son. I find it almost impossible to empathise with this guy. Perhaps he grew up with chickens, and had observed that a clucky hen can indeed be pacified by giving her the egg of another chicken, or even a golf ball. It is a spectacular feat of dehumanisation to believe that a human child can be swapped in the same way, and that a human mother would silently make do with a ‘dummy egg’.

COMMON CHANGELING SOCIAL PRACTICES OF THE 20TH CENTURY

But then I think of my own country: 1920s colonised Aboriginal Australia. The worldwide hegemonic view of the era emerges: It was widely believed until the second half of the 20th century that children of disenfranchised classes and races could be taken from parents without inflicting intergenerational trauma.

Practices around closed adoption worked on the same principle, right up until the 1970s.

A FRESH SPIN ON THE CHANGELING PLOT

How does this relate to Shirley Jackson’s short story? “Louisa, Please Come Home” is a different spin on a very old changeling story. This isn’t a ghost story, but feels like it has ghosts in it. This isn’t a changeling story either, but feels like there’s a changeling in it.

Who has Louisa been exchanged for, though? Not a real person, but a ghost of a person: The person who exists only inside her bereft mother’s imagination.

SETTING OF “LOUISA, PLEASE COME HOME”

DURATION

a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

LOCATION

Shirley Jackson lived and wrote in North Bennington for 17 years. This wasn’t the busy part of Bennington but in a former mill and factory town about five miles northwest of Bennington’s downtown.

She’d have lived there longer if she hadn’t died at the age of 48. So what’s this got to do with her story, “Louisa, Please Come Home”?

Biographers believe this short story — along with “The Missing Girl” — is inspired by the seven people who disappeared in the woods around Bennington between 1945 and 1950, and that the story is imaginatively set around somewhere in America like Bennington.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

Only one of the missing people of Bennington was ever found (dead). Police found no evidence of foul play. Instead, it must have felt to the left-behind as if the woods simply ate people up, and that it was possible, frequent and plausible to go missing forever without a trace.

Among the the Benington missing:

- A 75-year-old man who never came back from a deer hunt in 1945

- An experienced woman hiker two weeks later

- Paula Welden in December 1946 was widely reported missing in the media, because her father kept public attention on his missing daughter via anxious pleas on the radio.

True crime writers have delved into these (unconnected) disappearances in some detail. We can be certain they were on Shirley Jackson’s dark mind, and on the minds of everyone living within radio range.

WHEN IS THIS STORY SET?

If “Louisa, Please Come Home” is inspired by real world events which happened in the 1940s, we can deduce the story is set in the 1940s unless told otherwise. But to me this feels like a ghost story set in the fairytale realm and runs on ‘fairytale time‘.

From Greek we already have useful words which draw a distinction between linear, realworld time and eternal, mythic time: chronos and kairos.

The story of a missing girl who disappears, and whose mother repeats the same plea over and over, like a ghost returning night after night to wail in its former dwelling, is a story set in the mythic, primordial time of kairos. When the mother returns to the radio every year at the same time, she is performing a ritual. Ritualistic behaviour is the surefire giveaway that a story operates on kairos rather than chronos.

ARENA

It’s interesting that Louisa doesn’t go far from her home.

MANMADE SPACES

Louisa appears to come from a ‘respectable suburban family’. Time and again, American storytellers portray the suburbs as a place of spiritual death.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

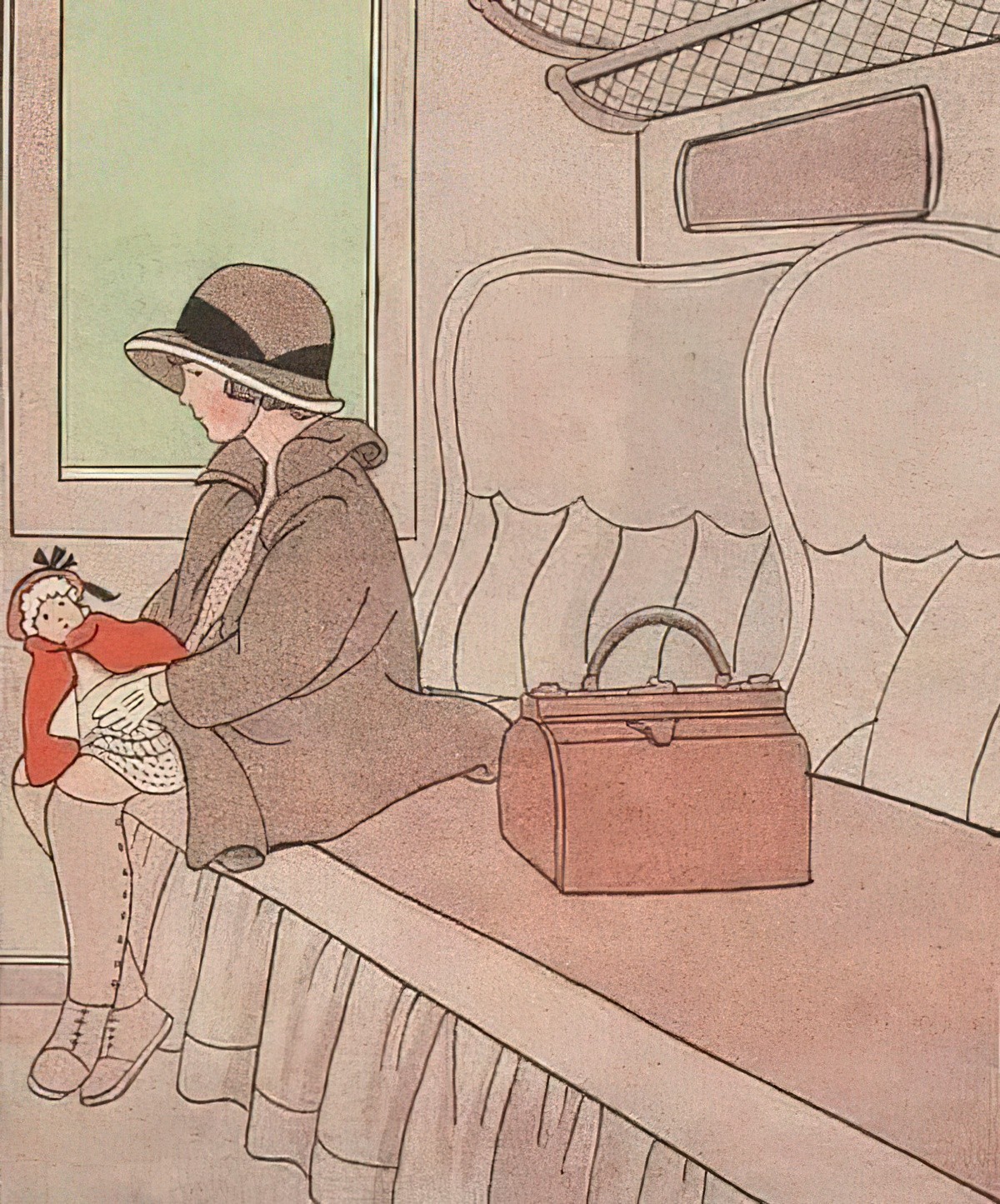

The lack of technology is important to this story.

Realistically, how much more difficult would it be to run away now? A 19-year-old would carry a mobile phone. Modern workers receive pay via bank account, traceable by the tax department and police.

Perhaps the modern analogue of Louisa is an undocumented immigrant.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

This refers to he land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories.

This story tricks us into thinking Louisa is wrong about her family. I believed she is wrong because she has completely underestimated the havoc she selfishly wreaks upon her family after leaving home for no good reason. The reason Shirley Jackson gives: The sister is getting, what she feels, is a disproportionate amount of attention. Is this a good enough reason to leave home forever, without leaving a forwarding address. I would say no.

But the unexpected ending showed me that, actually, Louisa’s dissatisfaction was not at all about the sister getting more attention. It was about Louisa getting none at all. No matter how much attention we get, if people don’t see us for who we really are, it counts for nothing.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “LOUISA, PLEASE COME HOME”

SHORTCOMING

LOUISA AS CHILDLIKE

I argue above that “Louisa, Please Come Home” works not with chronological time but in the realm of mythical kairos. Until about the age of five, we all operate on kairos. Young children are expert at living in the moment. After that, we develop a concept of chronological time. Louisa is a young woman, but she is a childlike figure.She seems to operate on kairos. She solipsistically wanders around the world, unconcerned about the effect her disappearance might have on her family.

LOUISA AS SOLIPSISTIC GHOST

This aspect of Louisa reminds me of the main characters of The Others. The Others is a ghost story, whereas “Louisa, Please Come Home” is ostensibly not. But in an expanded definition of ‘ghost story’, any loved one who disappears becomes a ghost, whether they are dead, or living an ordinary new life just a few towns over.

Louisa’s psychological need is to put some space between herself and her family. Her moral need, after three years and a preceding character arc, is to reconnect with her family, though only after provoked.

For most readers, I suspect 19-year-old Louisa Tether is not easy to identify with. Few of us can imagine leaving our friends, family, everyone we know, and starting a new life elsewhere without emotional consequence. To add insult to injury, Louisa takes off the day before her sister’s wedding.

Interestingly, Jackson tells us how Louisa ran away from her family, but she leaves us on our own to extrapolate the why. Sometimes, what’s left off the page is more intriguing than if it had been explained. We will only find out at the end why she left.

Also, if Jackson were to tell us why Louisa ran away, Louisa would need to be an emotionally aware storyteller who can understand herself sufficiently to even know, and then to put it into words.

DESIRE

“She would never have wanted to spoil my wedding,” Carol said. But she knew that was exactly what I’d wanted.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

If interesting main characters require moral shortcomings, Louisa is a brilliant creation. She ruins her own sister’s wedding by turning the focus onto herself. So what is her deeper desire? It would be a mistake to jump to the conclusion that Louisa wants to be the one in the limelight. Her subsequent actions — quietly toiling away in a stationery store — suggest she doesn’t want that at all.

But there is another type of personality who loves to be both noticed and invisible. Louisa achieves the perfect level of attention for herself via her annual fame with the birthday broadcast. Some people get their kicks from invisible visibility.

OPPONENT

Since Louisa wants to run away from home, annoy her sister and also to remain remembered but anonymous, the opponents are the character who stand in the way of that.

In this case, it is Paul, introduced early to provide cohesion. (It’s not a good idea to introduce important characters late in a short story. If a character is needed towards the end, introduce them early, somehow.)

There was only one bad minute. Paul saw me. Paul always lived next door to us. Carol hates him more than she hates me. My mother can’t stand him, either.

Of course, he didn’t know I was running away. I told him what I had told my parents. I was going downtown to get away from all the noise. He wanted to come with me. But I ran for the bus and left him standing there.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

Mrs Peacock

If Louisa Tether has an ironically symbolic name, we might look for reasons why Mrs Peacock has been named after a bird with spectacular plumage.

What we know about Mrs Peacock:

- She can be quick to take offence

- She is fanciful

- ‘Proper living’ lady who believes in filial piety

- She and Louisa hit it off right away, according to Louisa

In history, myth, legend and lore, the Peacock symbolises: Nobility, Holiness, Guidance, Protection and Watchfulness. If this is the case here, Mrs Peacock, too, has an ironic last name. But when I think of peacocks, I think of posing — show without substance.

This is precisely what Mrs Peacock does with the wholly imagined story of Missing, Murdered Louisa. Like Louisa’s own mother — foreshadowing the mother’s response — Mrs Peacock is so wholly focused on appearance that she can’t see the reality in front of her.

PLAN

I bought a round-trip ticket; that was important, because it would make them think I was coming back; that was always the way they thought about things. If you did something you had to have a reason for it, because my mother and my father and Carol never did anything unless they had a reason for it, so if I bought a round-trip ticket the only possible reason would be that I was coming back.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

Normally, you’d think someone’d have more trouble running away and staying unfound. Shirley Jackson subverts that expectation; it’s remarkably easy for Louisa to do just that:

Anyway, Carol’s wedding may have been fouled up, but my plans went fine—better, as a matter of fact, than I had ever expected.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Louisa is eventually recognised by someone from her old life. Her inner struggle is left off the page. Shirley Jackson was expert at writing simply prose lacking in interiority in a way which forces the reader to fill in the gaps for ourselves. In this way, she requires readers to contribute to the story. (See her pull off this trick really well again in her short story “Afternoon In Linen“.)

ANAGNORISIS

Louisa and the reader learn the same thing at the same time: Louisa was right all along. She didn’t think about the effect her absence would have on her family. Now she has it confirmed: They haven’t missed her at all. They’ve missed the idea of her.

This Anagnorisis propels the story into the realm of psychological horror. This is a spin on the changeling story; there’s no replacement, but there could be, at any moment. Imagine for a moment that your mother doesn’t really love you, despite all appearances and actions to the contrary. Imagine that she loves the idea of having a child in the vaguely same form as yourself.

Imagine, too, that you come home from school one day and find that your own family doesn’t recognise you.

NEW SITUATION

Louisa leaves with a twenty-dollar note, gives it to Paul (who helped her get back to her family) and listens to her mother talking to her once a year for years to come.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

There’s no question about Louisa staying on the stoop trying to persuade her mother that she is, in fact, Louisa. I believe this closes Louisa off to her natal family forever. I doubt she’ll give them much thought at all over the course of her life, except on her own birthday.

Meanwhile, the mother will continue to grieve, but for someone she never had.

RESONANCE

There’s a well-known 1948 science fiction short story called “Knock Knock” by Frederic Brown. It begins like this:

The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door …

Knock Knock

Contemporary science fiction collections include at least one story which opens in similar fashion, opening with the terrifying image of “the last man on Earth”. Even outside the speculative genres, the “last person, completely alone” plot taps into a deep human fear. We have not evolved to exist in isolation, yet nor can we trust everyone we meet. We all must live with this uncomfortable reality.

I definitely get “Knock Knock” vibes from “Louisa, Please Come Home” which is, only on the surface, a completely different kind of short story. The difference is, Louisa only realises she’s completely alone at the end of the story, not in the opening line.

THEMES IN “LOUISA, PLEASE COME HOME”

THE ROSE-TINTED GLASSES OF LOVE

We idealize the people we love. Sometimes the person we want to see is nothing like the person who actually stands before us.

I’m first reminded of a voice excerpt on the Paris Wells album Various Small Fires. A man says:

My heart and brain concur.

Marvin Wildstein

I love but one more than you, the one I thought you were.

(You’ll find it at the end of “No Hard Feelings”.) In issue #383 of The Brag, Paris Wells explains this is poetry by a guy they met in a Jazz club in New York — “this old lovely Jewish guy in a wheelchair.” His name is Marvin Wildstein and she just had to put him in the album. (Here’s another of his poems.) Marvin died of pneumonia early April 2015.

Is it possible to be in love with someone who doesn’t exist? Atheists would say yes. Perhaps we are all in love with someone who doesn’t exist, insofar as it’s never possible to know another completely.

I tried to imagine my own mother; I looked straight at her.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

We come across hundreds of people each week but we know very few of them at all, most of them remaining completely unmemorable. Sometimes, the only way we can be the centre of attention/achieve fame is by doing something terrible.

‘It’s funny how no one pays any attention to you at all. There were hundreds of people who saw me that day, and even a sailor who tried to pick me up in the movie, and yet no one really saw me.’

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

People seem to prefer elaborate stories of kidnapping and gore over simple realities such as ‘She just ran off’. The former is almost easier for them to understand.

People never seriously believed that anyone would go to Chandler from choice.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

COGNITIVE BIAS

We explain away the world so we can get through it. With Mrs Peacock as with all of us, our perceptions shape our expectations. When Louisa says, ‘But she kind of looks like me” Mrs Peacock makes up excuses as to why she couldn’t possibly be living with the runaway.

We are strangely slow to believe some stories but quick to believe others. Mrs Peacock does not see Louisa right there in front of her, but concocts an elaborate conspiracy theory, some of which she shares with Louisa:

“But the papers say there wasn’t any ransom note.”

“That’s what they say.”

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

This aspect of the theme reminds me of the way in which the Internet has brought conspiracy theorists together, and the way some ridiculous stories end up more believable than the more mundane realities.

INVISIBILITY

There must be thousands of 19-year-old girls, fair-haired, five feet four inches tall, weighing 126 pounds. And a lot of them would be wearing raincoats.

It’s funny how no one pays any attention to you. Hundreds of people saw me that day. But no one really saw me.

Louisa, Please Come Home by Shirley Jackson

Compare and contrast the character of Louisa with, say, Raoul Duquette of Katherine Mansfield’s “Je ne parle pas francais“. Both of these characters have extraordinary imaginative powers, able to completely reconstruct the realities of their own lives, leaving the past behind them, immune to regret.

But unlike Duquette, Louisa achieves this rebirth by remaining invisible. She doesn’t want to be seen. She doesn’t see herself as a character in a play, constantly on-stage, performing in front of an imaginary audience.

STORYTELLING TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

THE ENDING LINKS UP TO THE BEGINNING

This is a story that rewards a re-reading. Shirley Jackson almost nudges us towards a second reading by starting and ending with repeated lines. This circular plot ties into the kairos or repetitiveness, the cycle of life, punctuated by ritual. (Stories featuring girls and women are often circular in shape. In the West, circularity is linked to femininity.)

The unexpected response at the end changes the whole focus. Most stories about reunited people end with tears of joy. This is a subversion of the mythic reunion plot, in which a hero leaves home to fight some battle, overcomes many hurdles then returns home a changed person. (Changed as in ‘unrecognisable’. Ha.)

And why might Shirley Jackson have subverted this plot? Let’s go back to the quote I put at the top: “It’s always the hypothetical children we must save. Not the actual ones.” The author of that tweet wasn’t writing about this story. The thread is about conservative, evangelical American parents whose notion that they own their children affects a wide range of so-called “save the children” legislation, including but not limited to:

- The “Don’t Say Gay Bill”, which is not actually about cishet conservatives conflating gender identity and orientation with sexual acts. This bill is about preventing “anyone from teaching their children that other kinds of families are possible other than the iconic nuclear family.” It is not, in fact, about protecting children, since no one really believes gay teachers are showing kindergarteners porn.

- The eradication of gender affirming care for trans people. Thirty years ago it was gay people who bore the brunt of this “Won’t someone think of the children” panic. Not that it’s gone away, but conservatives are largely heaping their disdain upon trans people now. The trans community is tiny, which is precisely why conservative politicians use trans people as a political football in wedge politics (and not just in America — this is happening all over the world). It is never, ever about the actual children.

- The American movement against Critical Race Theory, which is not actually about making white kids feel ‘guilty’ but is instead, once again, about preventing anyone from teaching their children anything other than “bootstrapping success stories” about white families.

- Pro-life rhetoric, which is not actually about pregnant people harming their unborn babies (since white evangelical conservatives abort plenty of pregnancies themselves, on the quiet), but is instead about control of women’s bodies to uphold the gender hierarchy with cishet men at the top.

- The QAnon conspiracy theories proliferating today, which in turn come from Satanic Panic. This link is perhaps a little more surprising, but again it comes down to the idea that children must be protected by outside forces. “It’s always the hypothetical [so-called abused] children we must save [from hypothetical pedophiles]. Not the actual ones.”

In short, the expectation of “parental rights” (to own children and make them into parents’ own image) undergirds many bullshit arguments against progress, respect, healthcare and inclusion.

“Won’t someone think of the children” is distractionary. Be very wary whenever you hear that, or anything similar, when used not in the context of actually protecting children, but in service of a broader political point.

Here in Australia, a number of our worst mass murderers (e.g. the sociopath behind Snowtown) brought conspirators into their fold by persuading them that victims were abusing children.

Flash forward to 2022 and Vladimir Putin is using the same argument to commit mass atrocities (see the speech in which he invokes J.K. Rowling). This is what happens. This is the pinnacle. The view that parents own their children eventually leads to murder. We have seen it play out before in Nazi Germany. The first victims murdered were trans people, after a brief period of successful activism.

Before the Nazis came to power, Germany was one of the global centers of trans activism and home to a thriving subculture of people with transgender identities. You could legally change your birth-assigned sex in some German cities even before 1900. The Nazis changed this.

Transgender Identities and the Police in Nazi Germany

What does this have to do with Shirley Jackson’s “Louisa, Please Come Home?”

Louisa’s parents never saw their daughter Louisa as a person in her own rigfht. Put another way, her parents never saw her at all. They saw only the daughter they wanted to see. The ending clues us in to why she would’ve wanted to run away in the first place; she was basically an apparition.

I read her parents as the mid-20th century equivalent of today’s “parental rights” crowd. When Louisa returns to these parents after claiming her own identity, to them she is an entirely different person. Wholly unrecognisable. For parents, it is far more comfortable to hold onto a fictionalised image than to see your grown child as a person in their own right. This story is allegory for any real life parents whose children grow into their own politics, which don’t accord with their own.

The experience of revealing one’s true self to one’s parents and not being truly seen is universal; more commonly stark and upsetting among the queer community, of course, but also commonly experienced by children of immigrants, who have been enculturated differently from their own parents, and also bear a heavy burden of expectation. Emigration sacrifices made by the parents must come to fruition in the children.

There is always a gap between parents and children, if only because times change. Perhaps this partly explains why “Louisa, Please Come Home” remains popular with readers today.

COAT AS SYMBOL OF TRANSFERABLE PERSONA

When Louisa ditches the light coat given to her by her mother, she feels she has cast her old life completely aside. Louisa takes off her personality/identity just as easily as taking off a coat. This is the author asking us to consider that maybe ‘identity’ isn’t all that integral to ‘self’.

For more on coat symbolism, see here.

FURTHER READING

- The Happy Hypocrite by Max Beerbohm also explores the difference between a real person and an idealised version of that same person, through the rose-tinted glasses of a lover.

- For the same reason, check out “Something Childish But Very Natural” by Katherine Mansfield, about the limerance of new lovers. Of course, “Louisa, Please Come Home” is about familial love, not erotic love. But the skewed perspective is the same.