The Iron Giant is a 1968 science fiction middle grade novel by Ted Hughes, adapted for film in 1999 by Tim McCanlies and Brad Bird.

Brad Bird later wrote the screenplays for The Incredibles and Ratatouille. Tim McCanlies has worked on Denis the Menace, among many other things.

SETTING OF THE IRON GIANT

PLACE

Rockwell Maine, in a leafy, hilly suburb. The diner is the hub of the community. This is also where Hogarth’s mother works. Since waitressing pays so badly, this conveniently keeps Hogarth’s mother working long hours. Hogarth has plenty of time to himself. Lack of money is also useful to the story because Hogarth’s mother is keen to have a boarder, looking past the fact that Mr Mansley might be evil.

A shot of Annie reminds me of a shot from Thelma and Louise.

In general, parents who are tired and overworked are useful in children’s stories. It gets them out of the way. (See below.)

TIME

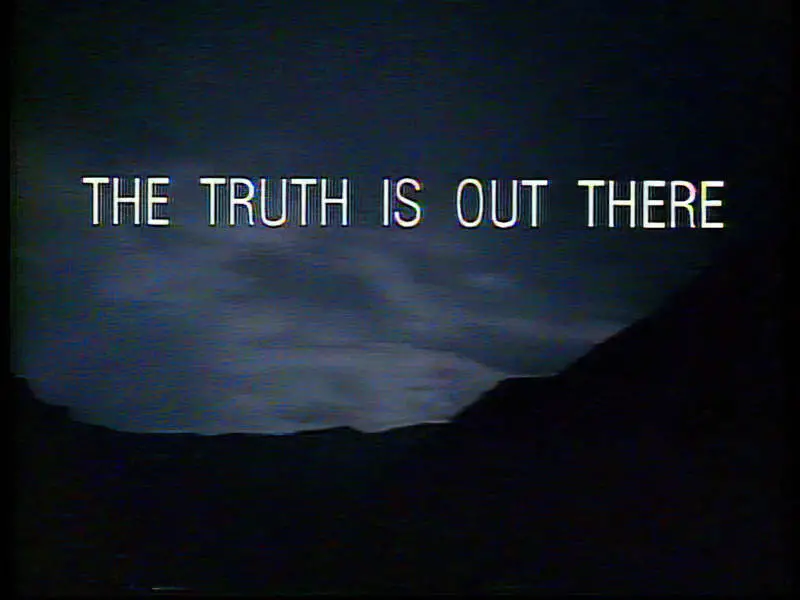

Though the novel was published in 1968, The Iron Giant is set earlier, in 1957. This is the era of the Cold War, an inextricable part of the story. At this time in history — it’s easy to forget now, or perhaps we’re starting to be reminded again — people lived in fear of an atomic explosion. They remembered the last ones. Especially in America, I’d say. (I’m not sure the fear was equally strong in New Zealand, where my parents were growing up.) American children were being taught what to do in the event of a bomb. (In New Zealand they were being taught what to do in the event of an earthquake.)

The Iron Giant takes place unambiguously in autumn. I wondered if this was mainly an aesthetic choice rather than a symbolic one (as seasons often are). Because a lot of the story takes place in a forest, which allows for a beautiful palette of orangey reds. At the end of the film I realised how well the red contrasts against the magical green bomb type thing released by the Iron Giant, symbolically contrasting this visitor from outer space with his environment, underscoring how he doesn’t belong there, and will never fit in.

The beautiful colours of autumn also serve to create a kind of utopia. And as we all know, utopias attract big, horrible events.

Note also that Rockwell, Maine, is set next to the ocean. I wondered if the town is inspired by Rockland, Maine, which is a real place. In fact, the town is named after Norman Rockwell, the famous American artist known for his utopian depictions of American 1950s childhood.

MILIEU

The 1950s was a weird decade. It seems a certain proportion of the population would love to return to this era. We think of the 1950s as emblematic of how families had always been — nuclear families with the father going to work, the mother making home cosy, full-time caring for the children, with White people dominating the utopian neighbourhoods, Black people out of sight, out of mind.

In fact, the 1950s were unique. That’s not how the world looked before, and the world will never look like that again. But because this decade is utopian in our collective memory, storytellers (and audiences) seem to really like 1950s stories. We have the threat of something, but it never really happens. (Atomic warfare.) Characters live with the memory of something terrible — Hogarth is a baby boomer, but did his father die in the war? Was his father a wartime soldier fling? (The movie doesn’t tell us.)

This era is well-known to be a patriarchal time. Part of Hogarth’s vulnerability is that he only has a mother. When his mother finds love with Dean McCoppin, Hogarth’s life has not only become more stable, but also more safe. He has a man in the house — not the fake man who flees in terror at the end, with the ironic name of Mansley, but a real man. Interestingly, the screenwriters of the 1999 film updated this book by making Dean McCoppin a hippie character. McCoppin is a bit of an anachronism — the hippie movement began in San Francisco at the beginning of the 1960s, so McCoppin is a few years ahead of his time. (Or super ahead of the curve.) I think the screenwriters took ‘year of publication’ as setting rather than ‘original year of setting’ from the novel.

But even in stories made today, the ultimate happy ending for a child living with a single parent is for the parent to find a partner. Indie coming-of-age drama The Birder’s Guide To Everything does this, as does horror film Lights Out, in which the older sister accepts advances from the sort-of boyfriend.

NOTES ON THE MOVIE

Though Ted Hughes didn’t live quite long enough to see the movie in its finished form, apparently he loved what the screenwriters did with his story. (Unlike, say, Roald Dahl, who refused to even watch Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.)

- Dean McCoppin is established as sympathetic with a Save the Cat moment. In the diner he backs up the local drunkard who has seen something, standing up for the guy even when the other men laugh. We initially wonder if McCoppin’s going to be friend or foe – he looks ominous with the dark glasses and slicked back hair.

- Hogarth is a trickster – doing exactly what his mother told him not to, eating junk food and watching scary movies. He is a boy who is influenced by pop culture of the 1960s. We’re reminded of this with the close up on the magazine. He’s off on a mission, but he thinks it’s a pretend adventure. He is also shown to be empathetic towards creatures with the squirrel. His mother tells us he has a history of collecting animals. For Hogarth, the Iron Giant is kind of like finding a woodland animal.

- The Iron Giant is presented as childlike first by mirroring Hogarth’s way of sitting on the ground. Then he offers Hogarth the gift of metal. This is a thank you present — the Iron Giant has been saved by Hogarth, who switched off the electric power station. Hogarth then trains the Iron Giant as if he’s a dog. My daughter says that the Iron Giant is her favourite character.

- Hogarth thinks he should tell an adult but, talking to himself, immediately changes his mind. “People always wig out and start shooting when they see something they don’t like.” When children in stories see something amazing and choose not to tell adults, this needs to be covered in the story. Hogarth lists a whole number of reasons for not telling. “If I tell Mom, that’ll start the screaming…” It turns out later that Hogarth has indeed talked to his mother. “That’s funny, he’s so tight-lipped now. The other night he was going on about hundred foot robots and so on.” But this is left off the screen.

- The Iron Giant is set up as a duckling type creature, following Hogarth as if he’s fallen in love with him in a maternal way. Now he starts misbehaving like a very dangerous toddler, eating the railway line. Hogarth’s motivation changes: now it’s his mission to stop this creature from wreaking havoc. Though Hogarth is the parent with the robot, at home he very much needs to be parented.

- Kent Mansley turns up — the opponent within the house. Even his name suggests that his masculinity is going to outstrip Hogarth’s. He’s also an opponent for the attentions of Hogarth’s mother – if Hogarth is not careful he might end up with him as his step dad. Mansley has a strong desire line of his own – to provide his boss with photographic evidence of the giant so that the government can send troops over to get it.

Conservatives always say that the scariest words are “I’m from the government and I’m here to help” Bur normal people find words like “Your insurance doesn’t cover that” and “We need to let you go, your last day is Friday” much scarier

Guy Freire

- The detached hand is a horror movie trope, though this one is mischievous rather than horrible. It was used more recently in The Cloverfield Paradox, with both comic and horror effects.

- The next problem is finding enough metal for the Iron Giant to eat. The scrap yard they find just so happens to belong to the Dean guy from the café, the one who let a squirrel out of his fly. He gets some great lines.

- Dean is portrayed as a hipster. He drinks coffee, a fairly new drink back then. (My parents started drinking regular coffee in the 1970s, though that was New Zealand.) He’s also an artist, and though left off the page in this children’s film, he’d be a dope smoking kind of guy who probably thinks he’s hallucinating when he sees a massive tin man turn up in his scrapyard.

- “I’m not the kind of guy who reports things to the authorities.” This is what Dean says when Hogarth says he’s not going to call his mom, is he? This is the lampshading the writers have already had to do for Hogarth himself – why wouldn’t an adult just call someone about this thing?

- Hogarth is adamant that ‘it’ is a ‘he’, though where does he get that idea? Robots don’t have gender markers. The viewer is not encouraged to question it. He is big and therefore dangerous and does not have a pink ribbon on his head and is therefore coded male. I bet he has a crop growing out the back.

- Hogarth spikes Mansley’s drink with laxative — about the only kind of drug spiking considered funny and therefore allowable in children’s stories. (Though if you’ve had it done to you as a high school prank, it really ain’t funny — my brother’s friends poured an entire bottle into his coke.)

- Hogarth considers it ‘undignified’ to have the mighty Iron Giant doing ‘arts and crafts’. While Hippie Dean lives outside the strict masculine gender norm, Hogarth doesn’t.

- The death of the deer symbolises what could happen to the Iron Giant if the authorities were to find him. The Robot doesn’t understand the concept of death and has to have it explained. Hogarth then goes into the concept of ‘souls’, lending a religious tone to it.

- Hogarth’s trickster side, established early, comes in handy later, when he sneaks out of bed ahead of Mansley, leaving behind the helmet to make Mansley think he’s still there.

- Over the course of the story, the Iron Giant develops his own motivation –- he wants to be Superman. Giving up on this dream, he sees the opportunity to save two little boys hanging dangerously off a building. For more on ‘main characters’ and ‘how do identify the star of the story?’, refer to my post on character functions. Both the Iron Giant and Hogarth change over the course of the story. Hogarth comes of age because of his bravery (and possible self-sacrifice) — he doesn’t know for sure that his presence is going to turn The Iron Giant from a raging maniac back into a loveable big pet.

MESSAGE OF THE IRON GIANT

The message in the movie is simplistic, but appropriate to its young audience:

“You are who you choose to be.”

As you can see, there’s nothing subtle about it. Hogarth even whispers it at the big big struggle scene, as voice over narration.

In order for this to work, the writers first establish a binary of good vs evil. The Iron Giant learns to be ‘good’ because he learns from Hogarth, who is likewise morally good. He is kind to animals (though perhaps catching them and bringing them into the house isn’t so kind, really). The Iron Giant has been created to destroy, however. It is only via his relationship with Hogarth that he can override this functionality. There is no moral ambiguity.

When we see hippie McCoppin wearing that yin yang dressing gown in his house, I do wonder if this is a wink to the adult audience — though this story establishes the good/evil binary, the dressing gown expresses a slightly more sophisticated (and modern) idea of psychology — that there’s a little bad in good people and a little good in bad people. We’ve since moved past this — the contemporary view is that we are all capable of great good and great bad, depending on context. Children’s lit is yet to catch up.

Moral Dilemma

Theme is expressed most clearly through a moral dilemma. In this story, it is the Iron Giant who has the moral dilemma — does he carry out his original purpose, to destroy mankind like a massive gun, or does he continue being good, as he has learnt from human Hogarth Hughes (note the alliteration). Hogarth stands for humanity in the humane sense. (I explained this to my daughter, whose initials are also HH. I’m not sure she caught my drift.)

For more on symbolic names, see this post.

Ideally, moral dilemmas have no easy resolution. But the choice between ‘not destroying the world’ and ‘destroying the world’ is not really all that hard — we know what he’s going to choose. There’s no reason for him to destroy us. But that’s because we don’t have the other side of the story. Who knows? Maybe the universe would be better off without humans? This is actually pretty similar to how war works — our side is the good side. We don’t think about the terrorists and their motivations.

The idea that ‘People choose to be good or bad’ applies to anyone, and to anyone with access to the nuclear codes. The main part of the message is that no one is ‘inherently evil’, which is actually an evolution on the fairytale binary.

A good/evil binary is comforting, and I think this is why it features so heavily in children’s stories. Ted Hughes wrote this story to comfort his children after their mother, Sylvia Plath, suicided.

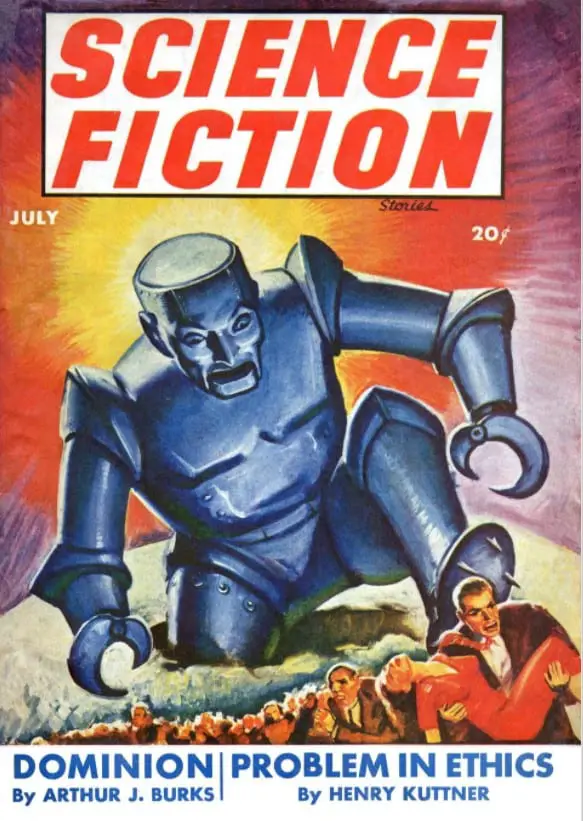

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ROBOTS IN FICTION

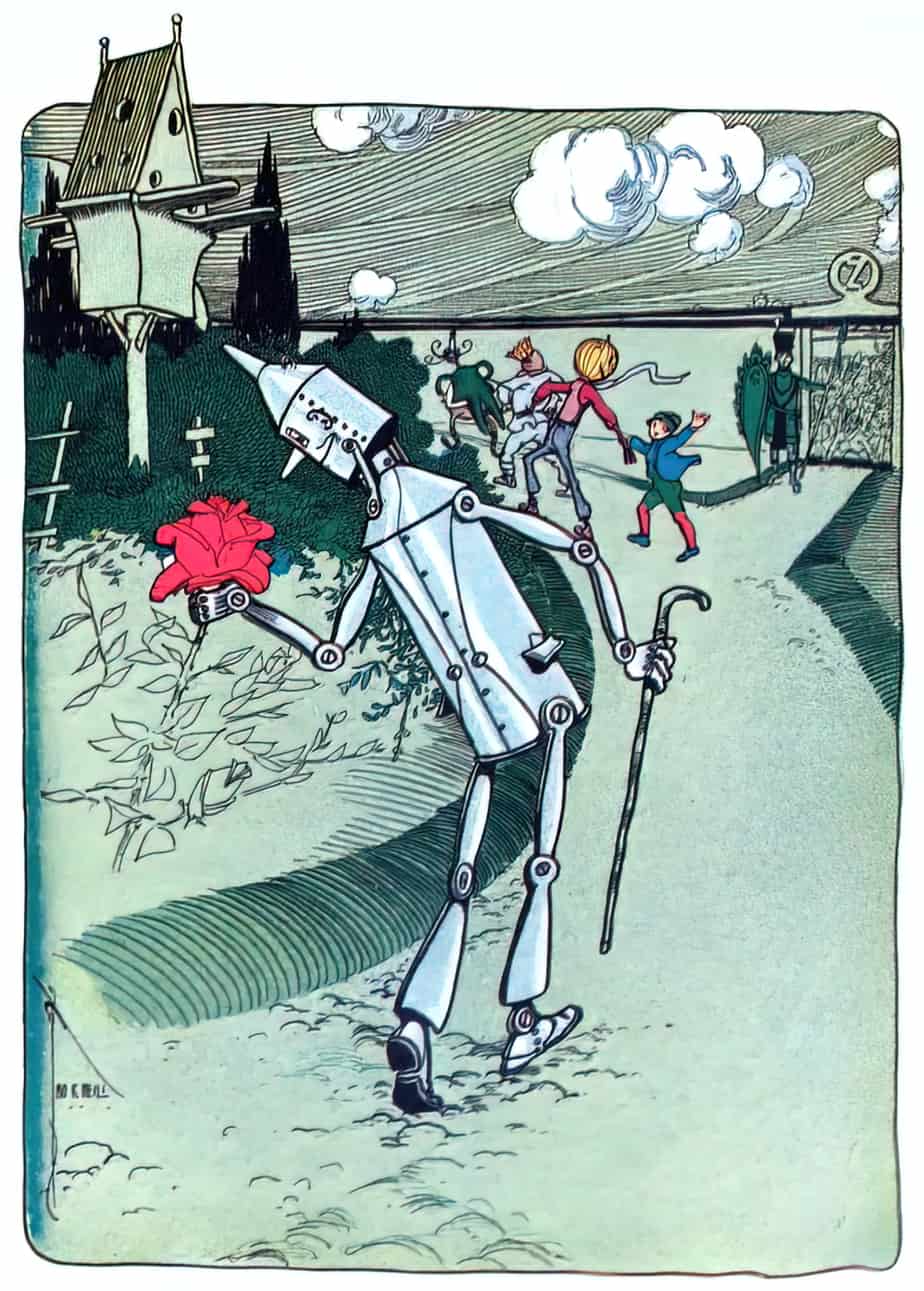

L. Frank Baum’s 1907 character was a precursor to modern sci-fi robots.

In Andy Buckram’s Tin Man by Carol Ryrie Brink (author of Caddie Woodlawn), Andy uses scraps around his farm to build several robots that will help him with his chores.

Since the first detonations of atomic bombs in the 20th century, pop culture has been morbidly fascinated by the realisation that humanity has developed tools powerful enough to destroy itself. For instance, Black Mirror reveals our fear of robots and algorithms we can’t control.

Today’s tin men stories are about:

- surveillance

- virtual reality

- artificial intelligence

What are we afraid of?

- privacy breaches

- a loss of the simple pleasures of real life and real human interaction

- automation leading to loss of our jobs

- loss of personal autonomy

- anything we can’t understand or imagine

We’re told to fear robots. But why do we think they’ll turn on us?

Modern Examples

Focusing on the dark side:

- Westworld

- Black Mirror

- H+

An article at LA Screenwriter divides robot characters in fiction into

- The robot as comic relief (robotic behaviour is inherently comedic)

- The robot as other

- The robot as protector

- The robot as friend

- The robot as us

The Iron Giant starts off as a friend then turns into a protector.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

In a future when humans are believed to be extinct, what will one curious robot do when it finds a girl who needs its help?

In the future, robots have eliminated humans, and 12-year-old robot XR_935 is just fine with that. Without humans around, there is no war, no pollution, no crime. Every member of society has a purpose. Everything runs smoothly and efficiently. Until the day XR discovers something impossible: a human girl named Emma. Now, Emma must embark on a dangerous voyage with XR and two other robots in search of a mysterious point on a map. But how will they survive in a place where rules are never broken and humans aren’t supposed to exist? And what will they find at the end of their journey?

Rise of the Machines from Smithsonian Libraries

Verbal Diorama discuss The Iron Giant at their movie podcast.

HitchBOT Was A Literal Pile Of Trash And Got What It Deserved from Deadspin