“Invisible Bird” is a short story by Claire-Louise Bennett, published in the print edition of the May 30, 2022 issue of The New Yorker. Like “We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek, which I read the other day, this is the tragic love story in which the time and place exerts its forces to remind us, falling — and staying — in love, is in large part circumstantial.

Stuart Dybek’s story is a great mentor text if you see shapes in stories and would like your theme to match the shape of your story. Claire-Louise Bennett’s story is a great mentor text if you’re writing (perhaps autobiographically) about a period in someone’s life, looking back after much has been forgotten, when memories come episodically. The difficulty with these stories is: How to end them? Also, when writing realism, not every remarkable life experience builds to a big climax. How to write a story which kicks an emotional punch without contriving some big battle scene?

Claire-Louise Bennett does a wonderful job here.

NARRATION

A female first-person narrator reflects upon a time in her young life when she had nothing. The story begins with her student life in London, when she lived a poor person’s facsimile of suburban life. Although in debt and living in a rented bedsit, she spent considerable time maintaining the two gardens ‘at the top of a smart tree-lined avenue’. Although the landlords appreciate the work she does in their garden, they must evict her, as she shows no propsects whatsoever regarding finding paid work.

A STORY OF MENTAL ILLNESS AND HOUSING INSTABILITY

Why has she not found paid work? Because she is experiencing debilitating anxiety. She finds solace in gardens, and in the common she feeds the ducks, meaning them to follow her. She also seems to be experiencing psychosis. She sees insects coming out of the corners of people’s mouths on the bus.

London provides too much mental stimulation, so she moves back to her unnamed English home town. Without saying why, her parents’ home is no good, either. Why does the author skip this bit? I think because almost any adult will relate. It doesn’t need spelling out that to move back to your hometown, reliant once again upon parents, is a regression to a childlike state, without true freedom. When deciding what to include in a short story like this, and what to leave out, remember: Include the ironic scenes. Meaning, include the surprising parts, where readers experience a meaningful gap between their own expectations and your scene.

In her small home town, the narrator moves in with ‘a recalcitrant man with lovely hair’, who becomes her boyfriend. We are not immediately told what makes him recalcitrant but it is clear by this part of the story that the narrator is looking back on her life after decades, as she has achieved a birds-eye understanding of how events connected, though she can’t remember the exact details.

The narrator confesses as she writes that she has forgotten numerous details, such as the third method of welding she was taught when enrolling in a welding course for women, or what time of day it was when the bus from Dublin airport drops her and the boyfriend midway down O’Connell Street.

WRITING A REALISTICALLY PASSIVE MAIN CHARACTER

The pair have decided to move to Ireland. The narrator has an instinct for the elements that make a story, because she tells the reader, “I don’t know what our plan was. I assume we had one because it wasn’t as if we’d decided to up sticks on the spur of the moment.”

They are soon out of money and the situation becomes dire. They are now unhoused, living on the street, finding shelter under the porticos of Dublin shops.

Next they meet a couple called Kenny and Anna. They’ve met Kenny at the Sackville Lounge (a famous real-world pub at 16 Sackville Place in Dublin.)

Kenny and Anna share a flat near Mountjoy Square. The narrator and her boyfriend move in with them.

SHOULD WRITERS FICTIONALISE TOWNS?

If you’re writing about a small town, either don’t name it or create a fictional one. If you’re writing about a major, well-known city, name it and also make use of its famous landmarks. Reasons for this: Anonymity is impossible in small towns and readers like to recognise landmarks in large cities. There’s the feeling of verisimilitude as well as the “Oo, I’ve been there!” trainspotting aspect.

SUMMARISING ABUSE

The narrator, whose name we still don’t know, is wary around Kenny. We are not told why, but she does describe their flat as like the set of a ‘kitchen-sink drama’. This phrase sometimes describes work which draws attention to the middle class and its problems. ‘Kitchen sink realism’ or ‘Kitchen sink drama’ were terms coined to describe a British cultural movement which developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For more on realism in storytelling, see What Is Realism In Literature?

WRITING WHAT IS NOT

With the benefit of hindsight, the narrator can articulate that the friends were all on edge “for the reason that we were all waiting for unrelated things, things we refrained from even hinting at in case it set someone off. There was an illusion of solidarity—really the underlying current was entirely factious.”

One effect of writing what is not: It slows down the pacing. The story varies a lot in this respect, making use of gaps all the way down to dilation. A perfect choice for a story of homelessness: Long stretches of nothing, dilating the days, but leaving the narrator with gaps when she looks back on these years from a distant, extradiegetic point of view.

MIXTURE OF VERB TENSES

She switches to the present continuous when describing how she would clean her clothing: “Fresh clothing becomes very important to me when I’m having a rough time. The smoother things are going, the grubbier I gladly get.” This tells us she continues to experience mental illness. It’s a lifelong thing.

DESCRIBING AN UNCANNY HOUSE

The only place the narrator feels safe in this strange, uncanny house of Kenny and Anna is the bathroom, which is clean. The smells remind her of something from long ago.

It also has no windows, a.k.a. no prospects for the inhabitants. No connection to the wider world, no connection to nature, and possibly a Bluebeard type house, where those who go in may never come out the same. There are elements of the Gothic in this house.

SWITCHING FROM ITERATIVE TO SINGULATIVE TO FOCUS THE READER’S ATTENTION

The story switches to the singulative with “One day…” Kenny and narrator’s boyfriend deliver a sofa to a brothel which has previously sustained a fire.

I began to suspect that Kenny’s enthusiasm for these periodic pints was at least partly motivated by a desire to get my boyfriend demeaningly twisted as often as possible. For one thing it put him in control and made him feel superior, and for another thing it caused a lot of trouble between my boyfriend and me, which upset and worried me deeply

“Invisible Bird”

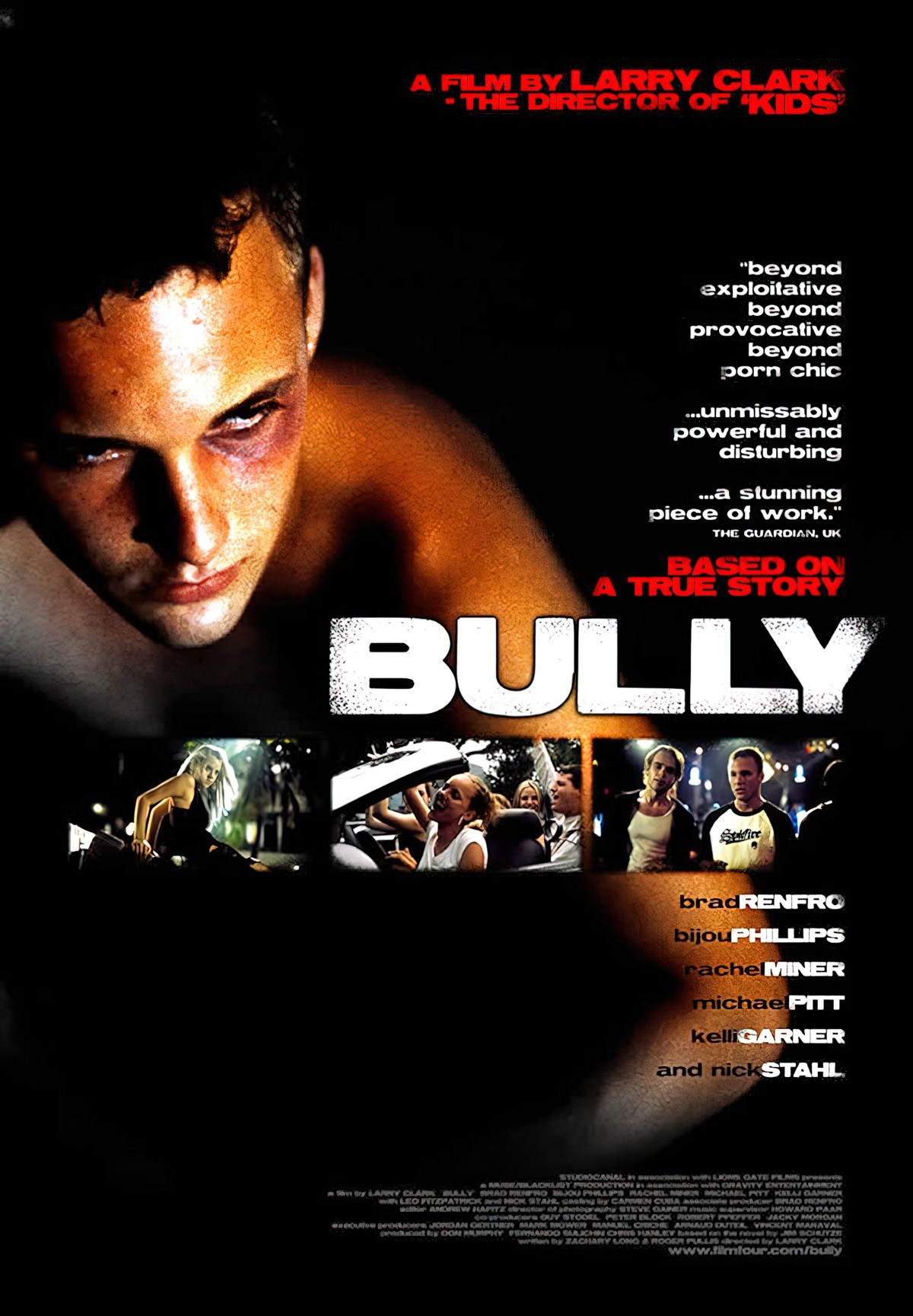

At this point the story reminds me of a 2001 film called Bully (18+) about a group of school friends in Florida who decide to murder one of the abusive young men in their group. The movie is based on the 1993 crime of the murder of Bobby Kent. Bobby used violence to exact control over the young men in his life as well as the women.

That’s not what the characters decide to do in this far quieter story. Instead the narrator and her boyfriend remove themselves from the situation and start living on the streets. Occasionally they get some reprieve from the streets by house-sitting.

THE PRECARITY OF HOMELESSNESS

The story continues in episodic fashion as the narrator is ripped off by an unscrupulous café owner before finding better employment.

THE ANAGNORISIS

At around this point I find myself wondering how this story will end. I’m expecting an emotional kick. Sure enough it comes, though not until the final sentence, after we learn that returning to ‘normal life’, in a house, with ‘increased income and increased outgoings’ means the narrator and her boyfriend barely see each other anymore. At first they are not used to living in a house and coveting things. They have become institutionalised, al fresco version, more comfortable on the street than in a house.

THE TERRIFYING PRECARITY OF ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS

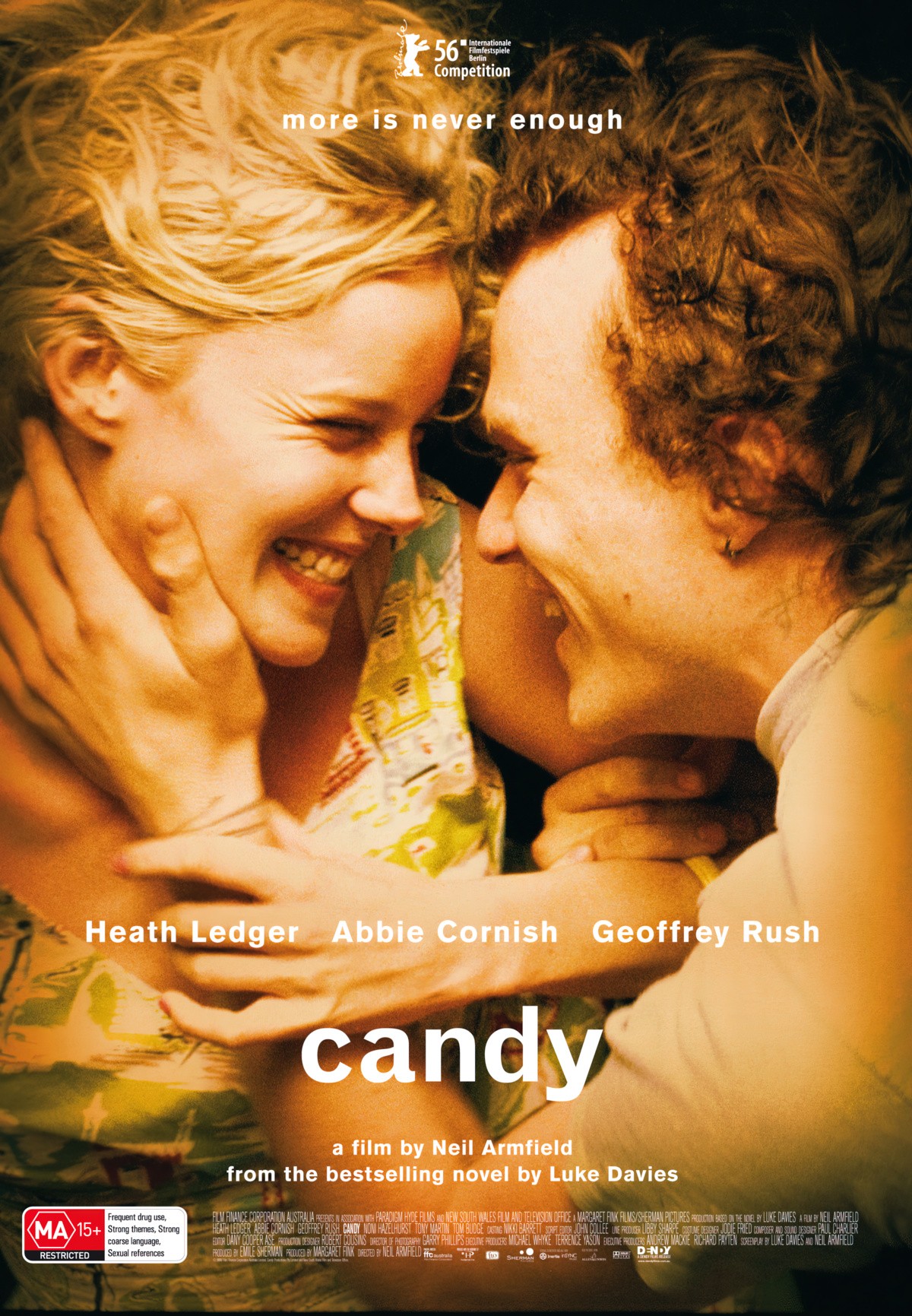

Now the story reminds me of a different film entirely — a 2006 Australian film called Candy starring Abbie Cornish and Heath Ledger, adapted from Luke Davies‘s 1998 novel Candy: A Novel of Love and Addiction.

“Invisible Bird” touches only briefly on the topic of addiction, unlike Candy, in which addition is the central monster which tears young lovers apart. In Claire-Louise Bennett’s short story, ironically, it is the mundane life which causes the alienation. A life full of work means they no longer have time for each other. When they were so poor they couldn’t afford anything to do, they spent hours playing hangman. Now they swap notes in passing, about mundane household matters.

Except the final paragraph reveals that the narrator is not talking about ‘now’, but some time in the past. The final sentence is as mundane and straight-forward as the life she now leads, but delivers the emotional punch: “There’s no way of asking him the answer—my boyfriend returned to England ages ago, and we are not in touch.”

THE MEANING OF THE TITLE “INVISIBLE BIRD”

Let’s consider the title of the story, which contains ducks early on, but otherwise no birds. Why is it called “Invisible Bird”?

The imagistic pattern running through this story involves what is ‘not’ and what is ‘almost’.

- In London the narrator barely leaves the house, going no further than the common.

- Her precious work of art is left in the boot of a car which her boyfriend sells.

- The narrator and boyfriend soon run out of money in Ireland. They have nothing, which is unexpectedly easier than having very little, since there is now no need to worry about how to apportion it.

- The constant reminder that she has forgotten much of the detail from this time, and is left with a general overview. This feels realistic for someone experiencing precarity, where accommodation and paid gigs change frequently and with little notice.

- When the narrator and her boyfriend dress in cheap finery and pose as lovers almost kissing, they appear frozen (uncomfortably) in time, but because the pose is so uncomfortable they can’t possibly maintain it. This maps symbolically onto the discomfort of romance which occurs during a time of housing instability. Compare and contrast with Frances McDormand’s character in Nomadland, another story of housing instability, and which almost becomes a love story but does not. McDormand’s character is much older. She has an entire life of experience behind her, and recognises that to get involved romantically in such a situation would lead to almost certain doom.

So, the ‘invisible bird’ of the title is the perfect imagery to describe a type of freedom (birds, flight, ya know) whose very freedom is contingent upon absence. What’s a visual representation of absence? Invisibility. The narrator doesn’t realise until her period of housing instability is over that to have nothing is a freedom as well as a cage.

Finally, we are left with the (death) imagery of a game of hang-man (which maps onto the death of a relationship). But the author wisely goes further than that, because the boyfriend has left an unsolved book title in a notebook. ‘One title remains a mystery’, and always will.

The narrator is coming to terms with the fact that life contains gaps — gaps of memory, gaps of knowledge, and periods of instability, with romantic relationships which feel at the time as if they could last forever, but then don’t.