Subversion of reader expectation to challenge long-held beliefs is one of the most difficult — and the most important — things storytellers can do.

It’s also easy to get wrong. Even teams with big budgets behind them often manage to go no further than pointing something out rather than leading audiences towards a critical reading of a text.

Some big name stories which look subversive at first glance fail spectacularly:

The game industry’s reliance on the female sacrifice’s presumed appeal should be critiqued and resisted. Tomb Raider (2013) appears to do just that, but the game’s use of Sam, Hoshi and Lara as sacrificial victims undercuts its subversive potential.

Andromeda on the Rocks: Retreading and Resisting Tropes of Female Sacrifice in Tomb Raider

For a children’s book example of subversion which fails, see my analysis of bestselling picture book The Day The Crayons Quit.

It’s not surprising that feminists are all over this aspect of literature. Storytellers have been trying to challenge gender roles for a long while now, and also getting it wrong. In Waking Sleeping Beauty, Roberta Seelinger Trites writes: “Novels that engage in simple role reversal are no more feminist than their counterparts.“

In this post I make a case against simple inversion, even if it hopes to subvert. I make a case against hipster irony. I make a case for a deep understanding of the cultural milieu before attempting a narrative which subverts it.

You never know when subverting your own point of view is going to lead to a new discovery for yourself.

Tim Baltz on the First Draft podcast

How to end a subversive story? Margery Hourihan (who wrote Deconstructing The Hero) offers some favourite examples of stories which successfully subvert the traditional heroic tale — the one which pits reason against emotion, civilization against wilderness, reason against nature, order against chaos, mind/soul against body, male against female, human against non-human and master against slave.

- Alice In Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, in which the entire world is turned upon its head;

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy and the others in this series, by Douglas Adams, similar to Alice In Wonderland in this manner, poking fun at the established order of things;

- Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George, because it does not depict wolves and nature as the enemy, over which to dominate. (However: American Indians in Children’s Literature does not recommend this book, which makes this story an excellent example of how a story can subvert one expectation while getting some other aspect completely wrong.)

- The Catcher In The Rye by J.D. Salinger, because the story criticises the values of post-war American patriarchal capitalism;

- Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter because although Peter is highly-spirited, he does not set out to ‘win’ anything over anyone else;

- Tehanu by Ursula Le Guin, because relationships between women are completely independent of men and is about the emergence of new ways from the old;

- E.T. which is a rare 1980s story about kindness, and the caring capacities of a boy.

Hourihan then describes why the endings of these non-heroic tales are so difficult to end well:

There is no thunderclap from Zeus or hot supper from Mother to signify approval of the hero’s deeds, the significance of the conclusion is often somewhat equivocal, and what will happen in the future is by no means certain. These stories do not imply that there are any final solutions to life’s difficulties; they do not evoke the ‘happy ever after’ heaven outside the text. The reader is left to wonder what Julie’s life will be like with her Americanised father and to wonder about the chances of survival for the wolves in the American north. Holden Caulfield’s future remains deeply problematic. Brian Robeson has been strengthened and matured by his experiences in the Canadian wilderness, but the reader must decide whether this will help him cope with his parents’ impending divorce and his own future. It is impossible to predict the futures of Tenar, Therru and Ged, but the one thing that is clear to the reader is that all will be changed utterly…

These stories demand active participation by readers and viewers. They demand interpretation and re-examination of received opinions. They demand the acceptance of uncertainty. But they reward their readers with intellectual, emotional and imaginative stimulation, with humour, with subtleties of insight, with opportunities to explore the perspectives of people different from themselves.

Deconstructing the Hero

Case Study: Pixar’s Brave (2012)

Pixar’s Brave was widely hailed as a welcome addition to a corpus of films which most often depict girls as princess types waiting to be saved. (Of all the reviews I have read of Brave, the review from Feminist Disney most closely matches my own impressions of it.)

Here’s why Pixar’s Brave is not subversive: Brave does not push traditional gender limits.

An academic from Emory University explains in this short video that Merida encourages girls to be independent, but within the fairytale structure of this arc, demonstrates that there are severe consequences to stepping outside gender roles. Merida unleashes a curse by daring to be different.

(It didn’t help that the woman writer of Brave was let go partway through production, and didn’t get to finish the story the way she had wished.)

THE INCREDIBLES

A better representation of girlhood in animated film is that of Violet from The Incredibles, who uses her super-power of invisibility to create a force field around herself. But there are other issues with this story — again, Violet exists — as most fictional female heroes do — within the realms of her family. Writers didn’t give her the opportunity to leave the family and seek independence, though they often give that opportunity to masculo-coded characters.

UP

Another Pixar creation, Up, is quite a gender-bender in this sense, because the boy who befriends the old man is desperate for the love of family rather than separating from the family to seek his boyish independence on the way to manhood. His is a more typically femme-coded storyline, in which family is important to him.

Case Study: Babette Cole

I didn’t fully understand my own problem with Brave until I took a close look at two picture books which parody traditional gender stereotypes. The first is Prince Cinders by Babette Cole and the other, a book called The Dragon Of Brog by Jean Hood.

This is from the final chapter in Deconstructing The Hero by Margery Hourihan:

Just as [Babette] Cole’s stories lampoon the stereotypes of large hairy masculinity and the swashbuckling hero who overcomes all difficulties, so Hood’s story ridicules the figure of the brave knight in armour whose profession is mayhem, and appreciation of the joke likewise depends upon familiarity with the originals.

These stories certainly raise the issue of gender, and provide effective discussion-starters for teachers. As Stephens says of Prince Cinders [by Babette Cole] ‘that abjection, humility and passivity now become deficiencies poses the question of why they should be virtues for the female’. But there are problems with these works that go beyond their parodic dependence upon the originals.

Their ridicule of the gender stereotypes is ultimately nihilistic for females. There are no admirable male figures against whom to measure the exploded stereotypes, and the attitudes of the princesses Smarty Pants and Lisa [and Merida] suggest that all males are contemptible nuisances. While this might amuse some girls because it is such a neat inversion of the dismissal of females in so many stories, it offers nothing except a sense of pay-back. Smarty Pants and Lisa [and Merida] themselves are little more than the old male stereotypes in drag: they are arrogant, self-assured know-alls with no empathy for others — hardly positive embodiments of the female. The trouble with dualism is that if you simply turn it on its head it is still a dualism. Inversion is not the same as subversion […]

Further, these stories fail to engage with the material they deride. Despite the patriarchal values inscribed in traditional hero tales the fields of folk tale, legend and romance are rich with potent symbols that work at many levels.

Deconstructing The Hero by Margery Hourihan

Hourihan does go on to say (of the picture books mentioned above):

Of course these stories do have an ideological content. They are celebrations of self-interest, of ruthless, unconsidered individualism. The behaviour of Smarty Pants and Lisa, who both want to do exactly as they like all the time, exemplifies the strident selfishness of the extremists who give feminism a bad name.

Deconstructing The Hero by Margery Hourihan

On this, I feel Brave does better than Princess Smartypants and The Dragon of Brog. By the end of Brave, Merida has changed the local law for everyone. From now on, no one will be forced to marry someone unless each is of the other’s choosing. Merida has been an activist for wider social change.

However, let’s not mistake this activism for a story-world with gender equality. That will not have been achieved until female characters are fighting for something other than female freedom.

Case Study: There’s A Girl In My Hammerlock (1991) by Jerry Spinelli

Main character Maisie joins the wrestling team in hopes of getting a boyfriend. She tries to transform herself into a boy, which of course does not work. (Dressing as someone else is a typical ‘mask’ plot.) She discovers that the boy she thought she liked is a jerk. But trying to gain power by acting male makes her little more than ‘a hero in drag’, which is irritating and retrograde.

By the way, ‘Hero in drag’ is a term used by Lissa Paul in her essay “Enigma Variations”.

(There are obvious transgender issues in these storylines, a topic I’ve covered elsewhere.)

Case Study: Samson: the Mighty Flea! by Angela McAllister and Nathan Reed

Samson the Mighty Flea opens with a male flea setting off to prove his physical prowess in a circus. The girl flea, clearly in love with him, packs his suitcase and waves him off but stays home, sad. This frustrates a feminist reader such as myself, who would like to see boys packing their own suitcases, and noticing other people’s feelings at least enough to acknowledge them. (I understand the girl flea packing his suitcase is to be read as a passive aggressive message that she’s glad to see the back of him, if his masculinity is so fragile.)

In the big, wide world, the boy flea is unable to impress anyone, and the ‘girl’ shows up out of nowhere. In a simple gender inversion, the girl flea impresses everyone instead. (This especially makes sense for fleas, in which there is no sexual dimorphism with regards to strength.) The boy flea falls in love with the girl flea’s display of strength. The story was a love story all along.

Soooo…. until I get to the very end, where the girl flea lifts the pea, I’ve sat through a hum-drum, frustrating, old-fashioned plot in which a girl supports a boy’s dreams as he attempts to prove himself in a masculine world (showing off his strength, in front of a large audience). The young reader is meant to have learned — I generously conclude — that girls are just as strong and just as worthy as boys, if not more so.

If authors are going to take problematic ideologies and subvert them, can they leave it until the very end? Does that still work? I really don’t know. I’m reminded of how critics said of Mad Men that Peggy and Joan were the ‘secret protagonists’. This may make sense for a story set in the 1960s, in which women had no choice but to find their own successes behind the success of a ‘cover’ man.

I cannot so easily explain it away for an atemporal picture book starring anthropomorphised fleas set in a fantasy circus.

Case Study: Tomb Raider

As Julie and the Wolves exemplifies, part of a text might subvert, but another experience of the text can undermine any attempt at subversion.

Through close textual analysis and Georges Bataille’s work on the role of identity in ritual sacrifice from The notion of expenditure (1933) and Hegel, death and sacrifice (1955), I interrogate depictions of women in need of rescue in Tomb Raider (2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015). I argue that at the narrative level, the game subverts this trope, but the consistent staging of endangerment, rescue and death as sites of pleasure for the player prevents the subversion from going any deeper than the text’s surface.

Andromeda on the Rocks: Retreading and Resisting Tropes of Female Sacrifice in Tomb Raider, Meghan Blythe Adams

Case Study: Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat by Roald Dahl

I explain in my analysis of “Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” how Roald Dahl’s mean-spirited short story was subversive for acknowledging that a 1950s housewife was a sexual being, but ultimately misogynistic and also, weirdly, Dahl managed to be acephobic before his time.

Note that there are two main types of short stories, and various types of short story endings. Lyrical short stories are quite likely to offer emotional closure without the hermeneutical (plot) closure.

Dahl wrote plotted stories, not lyrical ones, so new terminology may be in order. In writing a ‘twist ending’ for his ‘plotted’ (or ‘genre’) short stories, Dahl gave readers hermeneutical closure but his twists never did a thing to make up for the reality that he would throw certain groups of people under the bus for the sake of a bang. And when I say ‘certain groups’ of people, I mean everyone who wasn’t Dahl’s exact demographic.

So, when an author provides hermeneutical closure but messes up the subversion, what sort of closure have they messed up? We might call it ‘subversive closure’, I guess. Dahl failed many times at that.

Subversion, Irony, Satire and Parody

Satire and parody lend themselves to subversion. That’s their very purpose.

That’s because subversion involves foiling the expectation of your audience. Subversion aims to challenge pre-existing views. This is hard to achieve because the writer must intuit what the audience will expect, as well as what they already believe to be true about the world. The writer must have a solid understanding of psychology and of cultural tropes. (Note once again that simple inversion does not equal subversion.)

Irony has a very wide meaning and various subcategories and very much deserved its own post.

Hipster Irony

Hipster irony is a term sometimes used to describe ideas that would ordinarily be offensive, except there’s an understanding (true or not) that ‘everyone knows we’re not really sexist/racist/ableist etc. so therefore it’s not’.

There is a social function to this kind of humour. It says, “Other people are sexist/racist/ableist, but we, of course, are not. I trust you to get that.”

The game Cards Against Humanity took off like wildfire because it brings modern hipster types together, asking them to say offensive things in each other’s company, knowing that no one in the group would really believe such things.

In storytelling, sometimes a writer gets the willies and in an attempt to save themselves from criticism they lampshade the hipster irony by having the characters point out how sexist/racist/ableist something is.

Many examples of this can be seen in The Big Bang Theory, where the adorkable male characters say offensively sexist things all the time, but because the audience is supposed to realise these horrible things are horrible, we’re implicitly asked to forgive them. The following video does an excellent job of explaining the problems with hipster sexism. Everything said about sexism applies to the other bad -isms equally.

SATIRE

Satire is the ridicule of vice or folly. Its ostensible goal is to take an individual person, a type of person, an individual folly, or a type of folly, and expose it to public scrutiny.

Satire doesn’t have to be funny, though it very often is. Satire makes a political comment.

Gulliver’s Travels is a very old example — a work of political and social satire by an Anglican priest, historian, and political commentator. Jonathan Swift parodied popular travelogues of his day in creating this story of a sea-loving physician’s travels to imaginary foreign lands.

The Paddington Bear movie offers a gently satirical view of a particular kind of middle-class white English person. Pride and Prejudice does the same to the gentry.

Parody

A parody mimics the style of a particular genre, work, or author. The purpose is to mock a trivial subject by presenting it in an exaggerated and more elegant way than it normally deserves.

Parodies are the most popular and widely used form of burlesque.

An example (and subcategory) of the parody is the mock-heroic. Mock-heroic stories imitate the form and style of an epic poem (like Homer’s Odyssey); which is quite formal and complex. Mock-heroics induce humour by presenting insignificant subjects in the long, sophisticated style of epic poetry.

Annie Proulx’s Wyoming stories are often mock-heroic. In “The Half-Skinned Deer” we have a mythical hero who doesn’t quite make it back home. In “The Mud Below” we have a rodeo rider who thinks he’s a cowboy, but in fact he knows nothing about horses, or any of the traditional skills. He wants to become the bull — a symbol of masculinity — but is of course beaten by the bull.

In children’s stories, you’ll often find a parody in the form of a carnivalesque tale.

Genre Subversion

If Princess Smartypants and The Day The Crayons Quit teach us how not to do it, how do we create stories which genuinely subvert reader expectations, forcing readers to examine their prior beliefs?

One way of subverting reader expectations is to twist GENRE expectations.

The post WW2 anti-Western subverted the traditional Western by forcing the audience to endure the dark hardships of the people inhabiting the new West, challenging them to reconsider beliefs they may have had about the value of expansionism at all costs. The audience was ready for this of course, because they’d just lived through a couple of massive wars.

“Sea Oak” by George Saunders is a short story example of subversion well done. What is being subverted, exactly? Read the story for yourself before comparing your take with mine. (Note that Saunders is subverting a specifically American narrative.)

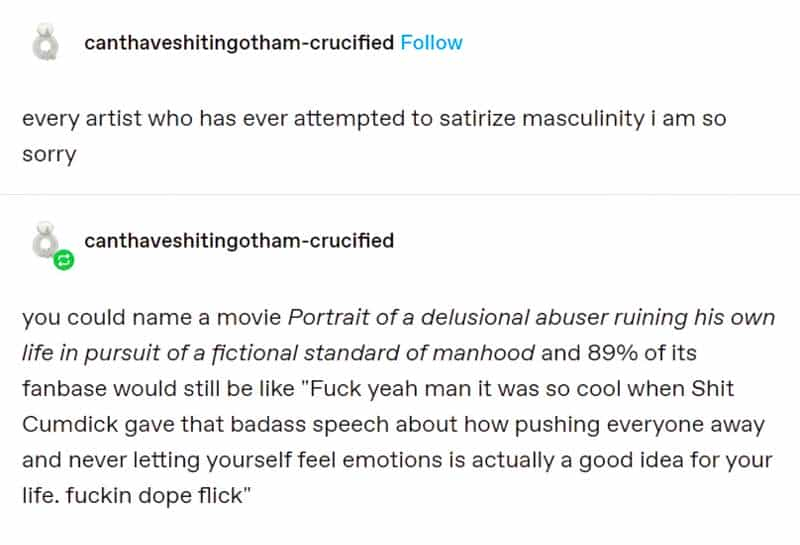

You Can’t Trust Audiences

The problem with subversive humour, such as irony, satire and parody, is that the audience doesn’t necessarily come to the party. This is true of audiences of all ages.

Larry McMurtry went out of his way to write an anti-Western when he wrote the Lonesome Dove series, but readers consider his main characters heroic, and the West feels to us, from the safety of our homes, like a kind of utopia. He did his best to fix this in the follow-up, The Streets of Laredo. Comanche Moon is very violent and dark. But if you only read the Pulitzer Prize winner in this series you may well miss the wider anti-Western messages.

Likewise, when test audiences of McMurtry’s Hud were asked which character they admired the most, a huge proportion of them said they admired Hud — written to be very obviously the tragic antihero. Instead, audiences were highly critical of his morally upright father.

Fast forward 40 years and audiences empathised with the morally despicable Walter White while criticising his wife for opposing him. You can’t trust audiences. There is definitely a case to be made for being obvious.

Apparent Subversion

A ‘snail under the leaf setting‘ has little in common with a ‘genuine utopia‘, and an ‘apparent subversion’ has little in common with ‘genuine subversion’.

As Heather Scutter comments with regard to jokes in children’s fiction, “apparent subversion may prove, on deconstruction, to mask a form of socialization which actually reinforces existing cultural values and beliefs, and encourages the child [reader] to accept the status quo“.

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature by Carolyn Daniel

I recently took a close look at the taxonomy of humour as suggested by the main guy at The Onion. One of the categories of humour he suggests is, of course, Irony. In that post I question whether young readers necessarily understand irony, which is a main feature of children’s humour, but then modern books (especially picture books) are aimed at a dual audience (adult readers and their children alike).

To take a popular middle grade example, about half the jokes in a David Walliams books are decidedly ‘adult’ — not surprising given that Walliams comes from an adult comedy background.

Jeff Kinney thought he was writing Diary of a Wimpy Kid for adults, and it remains unclear the extent to which kids ‘get’ the irony in his jokes.

Another question: Are kids who ‘get’ the jokes equally able to critique them? When Kinney makes fun of fat hairy people at the pool, do child readers understand that Kinney intends to poke fun at Greg Heffley for being grossed out rather than at the fat hairy people at the pool?

Animal Farm is often named as a satire on dictatorship, but Margaret Blount questions its success as such:

[Animal Farm] is a chronicle of the sad sameness of human nature and the ultimate absorption of every revolutionary movement — the endlessly turning wheel of conquest, power, corruption and decline. If you removed the moral, it would be no more memorable than the kind of sermon that tells one what ought to be done by giving a gloomy and prophetic chain of consequences that will be brought about if one persists in the way one is going.”

Margaret Blount

The Satire Paradox

“The Satire Paradox“ is a podcast from season one of Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History series. This tenth episode is well worth a listen for those interested in children’s literature because there are particular implications for writing humour directed at an audience who are still learning what is ironic, what is straight. And, as Gladwell points out, adults are hardly immune from interpreting a stand-up comic exactly in line with how they already see the world.

Basically, leftie comedy news anchors in America are popular with both right and leftwing voters because their jokes are interpreted in whichever way the audience sees fit.

The lesson here: Know your audience. Easier said than done.

Other Examples For Close Consideration

Work By Jeffrey Eugenides

Jeffrey Eugenides is a writer who likes to subvert genre. Below he talks about his books The Marriage Plot (a novel) and Fresh Complaint (his first short story collection):

I guess I wanted to subvert the genre. You have lots of stories where you have an older male preying upon a younger woman, so I was just trying to subvert the conventions of that kind of story. In that respect, [Fresh Complaint is] like The Marriage Plot, where I was trying to subvert the conventions of the marriage plot.

I think we’ve come to a point in literary history where anything you try to write, you’re quickly aware of the precedents of that kind of story. And there’s only two ways to do something new. One way is to make fun of the convention, to send it up. Which is all well and good, but tends to leave a kind of aroma of irony after it, which is a little bit superior in tone and mocking.

If you still care about your characters, and care about the world, you stay in the realistic mode, but subvert the tale and the normal telling of the tale by trying to express a different side of the experience. I didn’t want to make fun of the marriage plot only to make fun of it. I also wanted to write about young people in love, and what it feels like to be in love. I don’t want my work to just show how false things are, and how inauthentic everything is. Life doesn’t feel inauthentic or false to me. It feels quite real. And I’m concerned with it.

Vulture

ALL THAT I AM BY ANNA FUNDER

‘It’s the same old thing, isn’t it?’ he says. ‘All that we are not stares back at all that we are.’

Sometimes the imitation is brighter than the real.

All That I Am, Anna Funder

Some books aim not only to entertain but to exist as a mirror to the reader, asking readers to turn judgement inwards after first judging the main characters.

From a Goodreads review of All That I Am:

The main effect this book had on me was a deep sense of my own lack of similar courage...This book made me realise in what privileged and easy times we live today — and how little we are challenged to face the real life-and-death issues which are still there, even though they are invisible.

Hugo had no special voice for children. When he spoke to you he made you into your best self. [As if there is another self… on the assumption there is another self.]

I wonder, now, about interrogation chambers: why do they think bright light brings the truth out of people? They should try the seduction of shadows, where you cannot watch your words hit their target. [the juxtaposition of light and shadow]

But I must say it has been, in general, a boon not to have been a beautiful woman. Because I was barely looked at, I was free to do the looking. (Ruth: photographer, observer)

I wonder if this is the point.

The Case Of The Matriarchal Dystopia

Also in 2017 we have the highly lauded The Power, by Naomi Alderman. Barack Obama listed this book at the top of his favourite reads of 2017.

The Power also won The Orange Prize. This is a novel which reimagines an inverted dystopian future where everyone lives under a violent matriarchy rather than under a violent patriarchy, as we do now. This is an inversion, not a subversion. What is the ultimate message? “If women ruled the world they’d be just as bad as men.” This is a misanthropist view taken for granted, but is it really true? History has offered us just a handful of matriarchal cultures and they looked nothing like a dystopia, except perhaps for certain men whose idea of a good life was domination. When storytellers encourage audiences to fear the power of women, that is not helpful to the fight for equality. The Power is a failed subversion, if it ever set out to be one.

Hipster Racism and Hipster Ableism

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017) is very much reliant upon its audience picking racism and ableism for what it is. The most racist of the characters is punished heavily for his racism.

First, Sam Rockwell’s character is fired from his job by the new black chief, though it’s not for being racist, but for beating up a white guy. He is also punished in a fire, scarred for life by his burns. Again, this wasn’t punishment ‘for being racist’, which is interesting because thematically that’s the exact reason he had to be punished. If he had been punished directly for his racism, that would have felt too much like didacticism, at odds with the aim of the humour — to get the audience onside by trusting us to know racism when we see it.

Significantly, this racist character undergoes a redemption arc, realising that he can do something good for other people even when he doesn’t have to. It was the burning itself which taught him to dob in the rape-boasting soldier. We saw him dismiss someone else’s fire — “I’m not a police officer anymore so it’s not my problem.” This telegraphed the redemption arc to come.

Peter Dinklage’s underdog character is referred to as The Midget by everyone in the town. I saw this film in a theatre and the audience laughed every time a character called him a midget. Of course, if we didn’t know that midget is offensive, we wouldn’t be laughing. That would just be his moniker. Again, this is the writer drawing us in with a wink and a nudge, trusting us to get it. But what if you didn’t realise ‘midget’ was no longer an okay word to use for very real people with very real growth differences?

What is the real-world effect of hipster irony?

For story purposes we are encouraged to dismiss sexist/racist/ableist characters. We enjoy seeing them punished. Their outdated ideas justify the punishment. Hipster irony is also a comment on the very real racism and ableism that exists in many small towns such as Ebbing, Missouri. The writer of Three Billboards covers his ass not by lampshading at the dialogue level — unlike in The Big Bang Theory there’s no one sitting on a couch pointing out the racism — but by bringing in a black cop who is the most sensible, reasonable and level-headed guy in town. “See?” says the film, “This isn’t racist when the black guy is the best guy in town. Look at all these white fools.”

This trend looks to me like the PoC version of the Female Maturity Principle, in which black characters are given the job of educating racist white folk. Like female characters, these good guy black characters play ‘the straight man’, and enter the story as fully-realised (but flat) reasonably folk. As long as this is the case, PoC can never be the stars of the story, because the overriding feature of a ‘hero’ is the anagnorisis aspect. If you’re ever wondering who the main character of a story is, ask “Why changes the most?” That’ll be the star of the show. A character can’t change if they arrive on stage/on the page as a tool in the character arc of another character.

Though hailed as a feminist triumph for depiction of the Frances McDormand female antihero character, dig just a little deeper and you’ll see Three Billboards has done nothing new in its storytelling. In line with the last 3000 years of storytelling, the character arc was given to a despicable white guy.

It’s worth noting, too, that for people of colour living in small towns such as Ebbing, Missouri, the hipster racism fails to be escapist, because it’s an everyday lived reality. And that professional Black reviewers consistently rated this film lower than white reviewers.

Children And Irony

A child’s ability to understand irony depends on all sorts of things, including culture and subculture. A child from a heavily ironic family will naturally learn to pick irony, and use it, at an earlier age.

Certain cultures — Japan is one I know about — accepts and expects far less irony than typical Western subcultures.

Children don’t understand all the different kinds of irony all at once.

- Earlier studies believed that children didn’t understand irony until the age of eight or ten, but these studies were conducted in a lab environment and ‘irony’ was mainly limited to ‘sarcasm.’

- Later studies suggest children can understand hyperbole by age four.

- It takes another two years before children can start to get a handle on sarcasm.

- Sarcasm remains one of the easiest forms of irony for children to understand.

- Sarcasm and hyperbole are associated with positive experiences for children. (I would have instead guessed that sarcasm is not an overall positive form of communication.)

- Euphemisms and rhetorical questions are associated with conflict.

- Fathers are more likely to use sarcasm.

- Mothers are more likely to use rhetorical questions. (Rhetorical questions can also be used to silence. This is known as aporia. See: Thought-terminating clichés for other examples.)

Adults and Psychology

It’s not just children’s writers who should be thinking about all this.

In the “What Is Technology Doing To Us?” episode of The Waking Up Podcast, Sam Harris (who I don’t always agree with) talks to Tristan Harris, who touches on a peculiar psychological bug in which humans can be told a story, then told in the same paragraph that that story is blatantly untrue, but later it turns out we’ve forgotten the ‘it’s untrue’ part of the message and accidentally held onto the story.

This is perhaps because the human brain is wired really well to remember story, not facts. Harris touches on this phenomenon again in the “Living With Violence“ episode, in which Gavin de Becker gives the audience an example about violent kangaroos, then tells us that everything he just said is totally wrong.

Be careful when using this trick to try and persuade your audience of something. They may end up misremembering that kangaroos give clear signals before they kick you in the mouth. (They don’t.)

Humans have a bunch of memory errors. (It pays to be aware of these if you’re ever called to the jury.)

Some questions for writers of children’s humour

- If your viewpoint character expresses nasty views towards another person/group of people (I’m still seeing a lot of hatred directed towards fat people), will the young reader understand that ‘this is the character being awful because they are awful’, or is this character modelling the behaviour the author means to call out as wrong?

- Who is the likely audience for your particular story? Sophisticated kids with hipster parents? Or do you think there’s a chance this story has an international audience?

- If your subversive humour will be understood only by a certain proportion of young readers, does this matter? Menippean satire is a subcategory of satire aimed at attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities. (Alice In Wonderland is an example from the children’s book world.)

- Are you hoping to make fun of an individual (real or fictional) or of a (marginalised) group? Menippean satire passes criticism of the ideas of certain character tropes and on the single-minded mental attitudes, or “humours”, that they represent: the pedant. Common victims include the braggart, the bigot, the miser, the quack and the seducer. In children’s stories it’s commonly the schoolyard bully, the evil teacher, the overprotective parent, the prissy blonde girl. (Roald Dahl used both forms of mockery, occasionally going for the oppressor, but also, too often, going for the oppressed.)

- Let’s say you are going for Menippean satire. If your subversive humour were inadvertently swallowed as a literal statement, does this harm any group of people?

The Importance of Subversion In Children’s Stories

Alison Lurie, author of Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The Subversive Power of Children’s Literature makes the following argument about how children’s books can affect the common good:

The great subversive works of children’s literature suggest that there are other views of human life besides those of the shopping mall and the corporation. They mock current assumptions and express the imaginative, unconventional, non-commercial view of the world in its simplest and purest form. They appeal to the imaginative, questioning, rebellious child within all of us, renew our instinctive energy, and act as a force for change. This is why such literature is worthy of our attention and will endure long after more conventional tales have been forgotten.

Race, Culture and Power in Children’s Stories

Jack Zipes talks specifically about the role of schools in subverting the status quo, and it comes down to teaching students to be critical:

[Schools in the West] are geared towards making children into successful consumers and competitors in a ‘free’ world dictated by market conditions…If storytellers are to be effective on behalf of children in schools…it is important to try to instil a sense of community, self-reflecting and self-critical community, in the children to demonstrate how the ordinary can become extraordinary…Schools are an ideal setting for this ‘subversive’ type of storytelling…if schools want…to show that they can be other than the institutions of correction, discipline, and distraction that they tend to be.

Jack Zipes in Storytelling, Building Community, Changing Lives, 1995

In adult stories, the ‘absurdist’ genre comes closest to achieving the same ends, with absurdism’s emphasis on the corporate world. Perhaps subversive children’s stories are the childhood equivalent of absurdism, minus some of the darkest tropes. The corporation is swapped out for the school.

A Piece of Advice For Subversion

Yesterday I had a dayjob training in which the trainer said, re trends: “Look for the ask behind the trend.” She was talking about dayjob things but I think it works for book trends too. So currently thinking about the ask with vampires, or dystopian, or pirates, etc.

@Bibliogato

Someone I follow (unfortunately I forget who) pointed out that this advice “to look for the ask behind the trend” applies equally to subverting narrative as much as it applies to ‘picking the next trend’.

Someone else asked what exactly was meant by “look for the ask” (I’m glad they did). @sarahnlemon replied, ‘It means looking for the silent need that people are trying to fulfil.‘ The ask is not the metaphor. The ask is the reader’s need/pain point being fulfilled.

Others gave examples, mostly @Bibliogato themself:

The ask behind mysteries

Mysteries tend to get popular in times of uncertainty and social change/unrest because they’re all about restoring order to the universe.

The ask behind zombie stories

In a zombie story, half the population is ‘dead’ (asleep, not awake, not paying attention) and destroying everything that’s left for their own ends without any care or thought whatsoever.

The ask behind pirate stories in young adult literature

Pirate stories are all about self-organizing and self-empowerment in a time of perceived lawlessness.

The ask behind vampires

Vampires are a proxy for our fear of terrorists. They look like us, walk among us, we can be turned into one but they have alien desires which involve our deaths. Showing them as capable of love means they can be rehabilitated into the community. There’s an old theory that vampires become more popular in America when Democrats are in power because conservatives see Democrats as effeminate elites who suck the life out of the working class. (According to the same theory, zombies are popular with conservatives are in power, because Democrats see conservatives as mindless drones.) There are many, many theories about vampire fiction. Others have argued vampire stories become popular when sexual shame and fear peak in the culture. In the 80s with the AIDS crisis, for example, and in the oughts with Bush’s focus on abstinence—we get Twilight and True Blood.

I was at a writers’ workshop myself lately and the presenter advised us to write ‘subversive’ poetry. I didn’t put up my hand to ask what he meant us to subvert, because everyone was heads down, bums up working on a poetry assignment at the time, and this question might have derailed the entire session.

But it did strike me that so often when we sit down to write ‘subversively’, we may not have asked what exactly are we subverting here? This is an essential question and we must ask it of ourselves at some point in the writing process. The presenter was simply using ‘subversive’ as a descriptor, same as he was using ‘anarchist’. He wanted us to write ‘subversive, anarchist’ poetry because ‘kids are really drawn to it.’

Ask before writing: Whose need is being fulfilled?

FURTHER READING

For more on mythic structure — or the heroic tale, as it’s variously known — see this post.

What Really Makes Katniss Stand Out? Peeta, Her Movie Girlfriend from NPR, in which the Movie Girlfriend trope is gender swapped. (About The Hunger Games, of course.)

Dragon-Slayer vs. Dragon-Sayer is a paper by Keeling and Sprague which discusses the female hero as opposed to the ‘heroine’, which may be considered a different thing altogether — a ‘hero in drag’.

In an America controlled by wizards and 100 years behind on women’s rights, Beatrix Harper counts herself among the resistance—the Women’s League for the Prohibition of Magic. Then Peter Blackwell, the only wizard her town has ever produced, unexpectedly returns home and presses her into service as his assistant.

Beatrix fears he wants to undermine the League. His real purpose is far more dangerous for them both.

Subversive is the first novel in the Clandestine Magic trilogy, set in a warped 21st century that will appeal to fans of gaslamp fantasy.