Sticks and stones can break our bones, but words can break our hearts.

Tim Minchin

A quandary for writers of middle grade fiction in particular: By about age ten, regular kids have heard all the insults out there. They may hear far more insulting language than adults do on a daily basis. (Did you get called a poo head at work today? I didn’t.)

Yet if you want to write for middle grade, realistic swearing will never find its way into the hands of your readers. By upper YA, anything goes, although many writers for adults also like to avoid on-the-page swearing:

Wolfe Wolf crumpled the sheet of paper into a yellow ball and hurled it out the window into the sunshine of the bright campus spring. He made several choice and profane remarks in fluent Middle High German.

The Compleat Werewolf (1942)

Is there more swearing in children’s books today?

A cursory (ha) glance suggests that’s the case:

Swearing in children’s books, and even in books for teenagers, used to be pure anathema. SE Hinton’s 1967 young adult novel The Outsiders, for instance, an emotionally-charged account of youthful gangs clashing in Tulsa, features no language more colourful than “Glory!”, “Shoot!” or a very occasional “Hell!”

The Guardian

What Counts As Swearing?

But define swearing. Even Beatrix Potter, famous now for writing about bunnies in coats, made reference to swearing:

But Benjamin was frightened—

The Tale of Mr. Tod (1912)

“Oh; oh! they are coming back!”

“No they are not.”

“Yes they are!”

“What dreadful bad language! I think they have fallen down the stone quarry.”

Though we don’t see the bad language on the page, the mention of bad language prompts readers to recall what precisely that bad language might be.

The Case of Le Belle Sauvage

By all accounts, Philip Pullman’s Le Belle Sauvage (released 2017) may be something of a watershed moment for children’s literature, as it contains a lot of swearing. Pullman advocates for more naturalistic rendering of children’s speech, and because he is a superstar, it was up to him to try and get away with it, paving the way for those coming later. He explains his ideology here.

Swearing And Humour

Why is the video below so funny? Partly because what she says is unintelligible, until the the ice bucket gets dumped on her head. Then we know exactly what she’s saying!

Politics of swearing and childhood aside, what do most traditionally published and popular middle grade authors do when they need to depict swearing and insults without using the actual swearing and insults?

THEMATICALLY RELEVENT INSULTS

Newsprints by Ru Xu is a graphic novel in which birds feature heavily. The insults and swears are therefore often bird themed:

- Listen here, Humpy Dumpty, you stay off the roof! (Birds… eggs… Humpty Dumpty…)

- Good goosebumps!

For the human characters in Newsprints, the insults draw from cultural references such as nursery rhymes/classic literature and implements of the time. This is a steampunk book, where it’s assumed the children of this Victorian-esque era are reading nursery rhymes and Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland.

- Get back here, Bugle Brat!

- Catch me if ya can, Tweedle Dums!

- Still think you can fly, pal? (‘Pal’ sounds like an insult in this context because it’s ironic.)

NON-ENGLISH SWEARING

- In Pax, Sara Pennypacker includes a Haitian character whose swear word is dyableman. The child character learns it from the older mentor and starts using it himself. I can’t speak to the power of the word in Haitian Creole, but it translates as ‘damned, deuced, devilish’ — not at all powerful in translation. I’m wary of taking actual words from other languages, especially in a climate of cultural appropriation, but mainly because unless it’s your native language you don’t know the full power of the word.

- Fantasy authors can create entirely new languages and therefore entirely new curse words.

Lotta is four years old. She has a brother, Jonas, a sister, Mia-Maria, and two very patient parents. And then there’s Teddy Bear, the stuffed pig she never leaves behind, and her lovely neighbor, Mrs. Berg. But little Lotta above all has a lot of crazy ideas.

One day, she decides to go away, because she is now old enough to live on her own. Another time, she plants herself on a pile of manure in the rain to grow very quickly, like potatoes.

Never short of playfulness, she says “almost bad words”, loves donuts and lemonade, but especially escapades and hugs.

From the pen of the sassy Astrid Lindgren, a little hymn to childhood freedom in 15 playful, tender and whimsical daily adventures.

CASE STUDIES

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

The swearing is described as ‘cheek’ and takes place off the page, since the arrest of Toad is entirely redacted. Kenneth Grahame takes us straight to the court case.

The Clerk scratched his nose with his pen. ‘Some people would consider,’ he observed, ‘that stealing the motor-car was the worst offence; and so it is. But cheeking the police undoubtedly carries the severest penalty; and so it ought. Supposing you were to say twelve months for the theft, which is mild; and three years for the furious driving, which is lenient; and fifteen yeras for the cheek, which was pretty bad sort of cheek, judging by what we’ve heard from the witness-box, even if you only bleieve one-tenth part of what you heard, and I never believe more myself — those figures, if added together correctly, tot up to nineteen years –‘

The Wind In The Willows, Kenneth Grahame, Mr Toad.

YOU MAY ALREADY BE A WINNER BY ANN DEE ELLIS (USA, 2017)

The 13-year-old main character in this novel comes across much younger than she is on the page, and this is no doubt partly down to the author’s choice of language. Olivia Hales has a favourite ‘curse word’ which is ‘dumb bum’. She uses this over and over again — it’s her thing. If the 13-year-olds in your sphere are speaking like this, you’re hanging out in different circles than I am. However, stories are not the real world. We should be prepared to accept some differences. Perhaps the author/publisher decided to youngify (bowderlize?) the voice because the target reading audience is about 10-years-old. An older character uses ‘crap’, but that’s as cussy as it gets.

When Olivia gets really angry, she doesn’t swear. She indirectly threatens violence:

“Did you know a monkey can rip your face off?”

The girl’s eyes got all big and I was like, “Oh yeah. Yours too.” I said to the other secretary.

And then to the other one, “And yours for sure.”

***

Bart sees me.

I want to throw a car in his face.

It’s interesting what we think it’s okay to expose middle grade readers to. Nothing worse than dumb bum? But threats of violence as used in the real world is okay, so long as they’re hyperbolic. (No fear of someone actually throwing a car in your face.)

At other times the swearing is humorous, in a much-younger-than-thirteen kind of way:

“I am so sorry my daughter called me a butthead piece of butt face.”

“You scared the earwax out of her is what you did.”

While certain stand-alone taboo curse words are out in this middle grade novel, dismissively sexist language passes the gates. For example, Olivia constantly refers to her father’s love interest as ‘the redhead’, objectifying a woman by metonymically referring to her as a body part. There is also ableist language, but only used indirectly, not by the viewpoint character with whom we are expected to empathise:

There was Carlene and Bonnie and stupid Jared who called me a retard.

You May Already Be A Winner by Ann Dee Ellis

Different cultures deal with ableist language differently. It’s often said that there are no swear words in Japanese. But while profanities may be rare, taboos – and banned words – abound. Among these banned words (kotobagari) various ableist words make the list.

I offer this as an argument against publishers and authors removing naturalistic swearing from middle grade fiction. If it’s okay to use sexist and ableist language as used in the real world, why not use stronger yet (counterintuitively) more neutral swear words?

LOVE SUGAR MAGIC BY ANNA MERIANO (2017)

Love Sugar Magic is an own voices novel partly designed to introduce non-Spanish speakers to Mexican culture. The following snippet of dialogue is worded in such a way that the reader learns the Spanish word for cockroach, and also thinks they’ve got new insider knowledge on a good insult:

“Come on cucaracha,” Marisol yelled. She called Leo “cockroach” whenever she wanted to be nasty without getting in trouble for using bad language.

HURRICANE CHILD BY KACEN CALLENDER (2018)

Kacen Callender gets around the swearing issue by keeping the swearing out of the direct dialogue and telling the reader about the swear word in the narration.

“Caroline,” he says again, “what are you doing?” Except he says a rude word here too, and while my dad makes me so angry I can cry, that’s one thing he’s never done. He’s never cursed at me.

WHEN YOU REACH ME BY REBECCA STEAD (2009)

One way to get around swearing, which actually relies on the reader knowing the swear word in the first place. In this case, the word functions as a grawlix. (The ‘$@?%&*’ that you see in place of a swear word is called a grawlix.)

And as Mom likes to say, that’s a whole different bucket of poop. Except she doesn’t use the word “poop”.

The effect is two-fold:

- The author can’t be accused of introducing readers to new language because they won’t know what the mother said unless they already know it.

- The young reader feels smart and mature for knowing exactly what the mother really said.

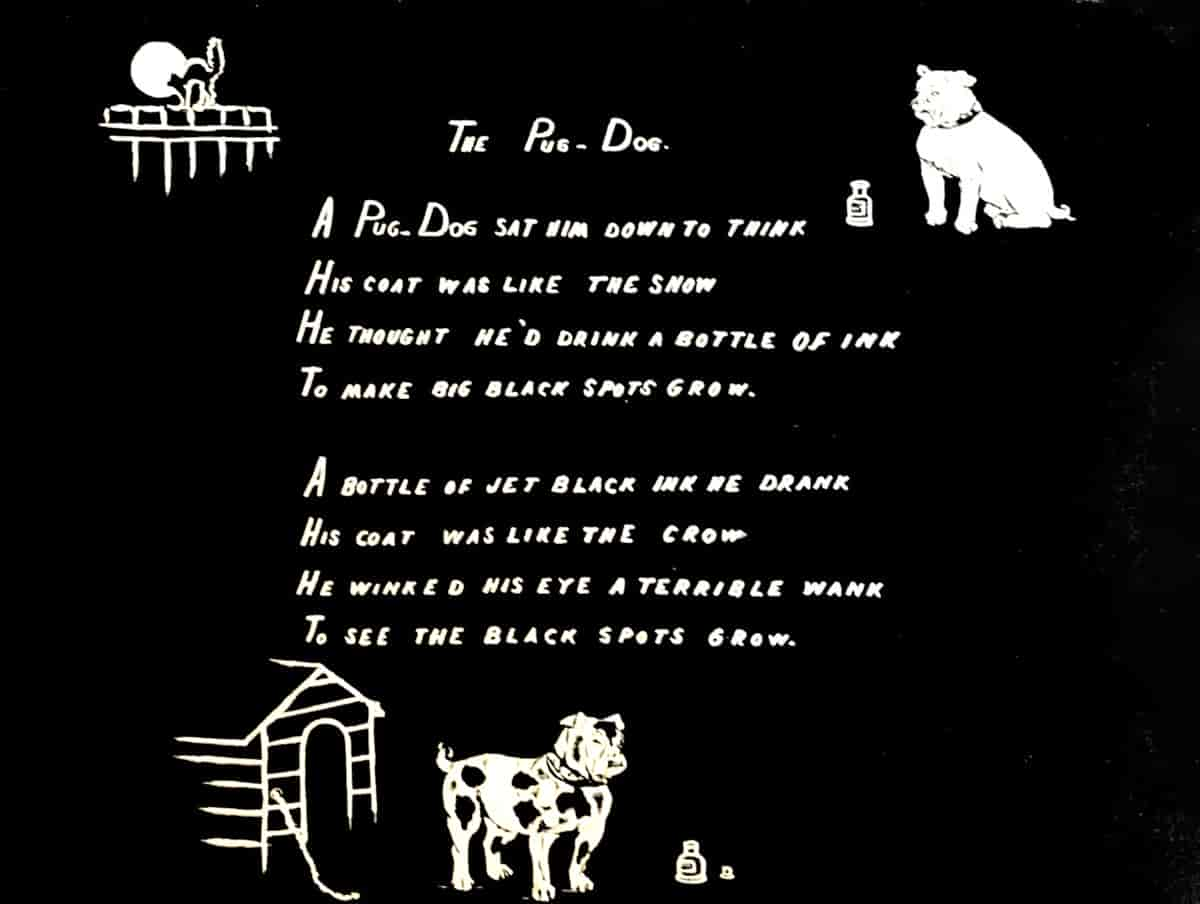

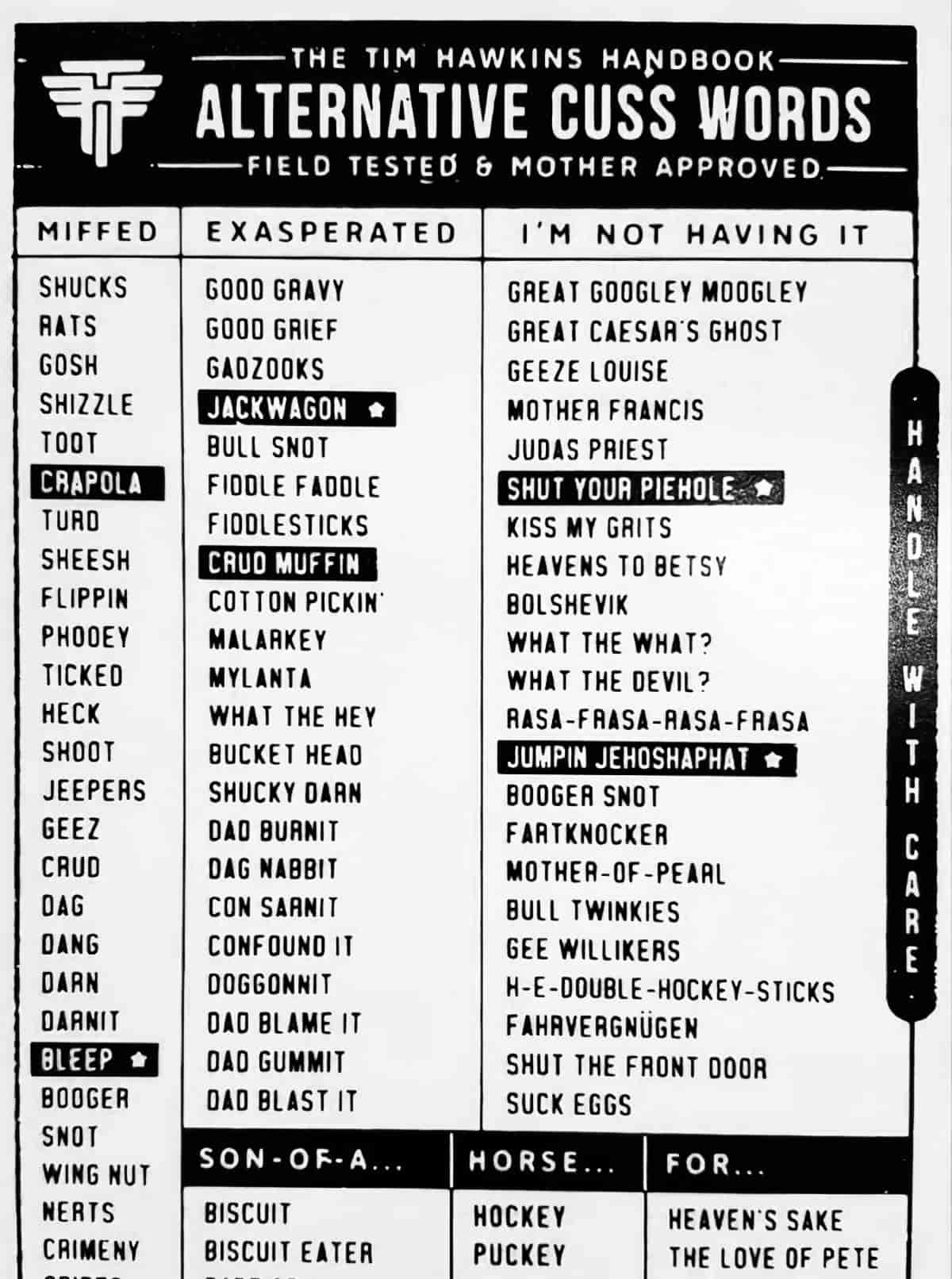

This leads me to my next point, which is why I have a liberal attitude around kids and exposure to swearing: A lot of ‘funny swears’ are very obviously based on real swears. The following chart sounds very American to me — none of these would be used in Australia unless the speaker were making a point of sounding American. A word like ‘bull snot’ is so obviously a ‘safe’ alternative to ‘bull shit’.

But then why is the bodily excretion of snot more acceptable than the bodily excretion of shit?

When coming up with replacement swears, make sure to find the equivalent number of words. They’re basically half rhymes or like something from the clues of a cryptic crossword e.g. Monday to Friday to replace Mother F*cking (courtesy of Snakes on a Plane).

Interesting though it is, the issue of swearing in children’s literature is sans logic.

An episode of Every Little Thing podcast (F**k yeah, Can Cursing Make You Stronger?) interviews a woman whose job includes replacing profanity in Hollywood blockbusters with tame versions. Children’s writers, I’m sure, would be keen to get their hands on her handbook.

One example from the handbook: Clown flusher to replace Mother f*cker, which the podcast conversationalists agree, sounds more offensive — offensive to clowns, at least. And what does flushing mean? The mind is encouraged to think about this, and it doesn’t go to great places.