“In-flight Entertainment” is a short story by Helen Simpson, published in her 2010 collection of the same name.

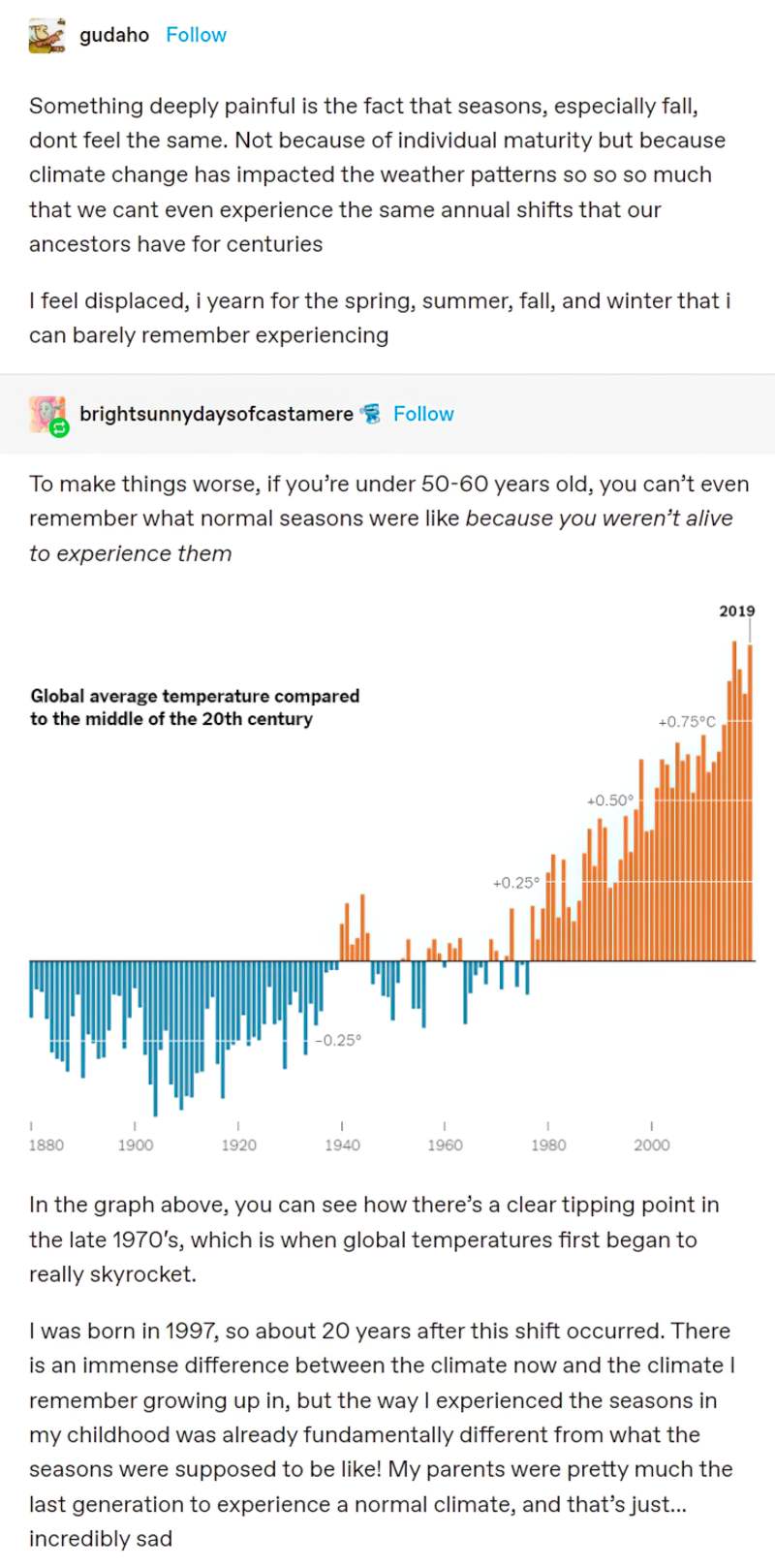

Thanks in large part to Greta Thunberg (not pronounced how I thought it was pronounced), 2019 seems to have been a turning point in general attitudes towards climate change. The phrase started off as ‘global warming’ (too benign), became ‘climate change’ and is now ‘climate crisis’. My own country’s online newspaper now has its own ‘climate’ tab, prioritising its importance.

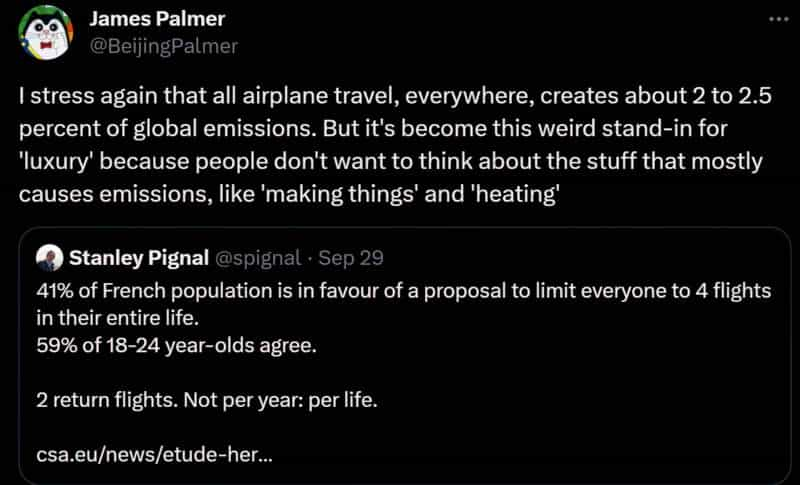

But even in 2019, those of us who think a lot about the climate crisis are still living in a bubble. Helen Simpson said in 2011 that if you suggest we might cut back on unnecessary air travel, reception is cold. While some people have indeed cut back on unnecessary trips, it’s business-as-usual.

With the climate crisis as focus, “In-flight Entertainment” is a short story about difficult conversations in the face of unwelcome yet inevitable change, and our ability to ignore what we don’t want to hear and go on with our lives. In the past, and on an individual level, this is a wonderful adaptation. Sometimes I wish I was a climate crisis denier. I think I’d be more content.

Which cognitive biases are we talking about exactly? Infuriatingly, it’s a raft of the things, all working together:

- Hyperbolic discounting: We are very bad at understanding statistical trends and long-term changes, paying attention to immediate threats.

- We overestimate threats that are less likely but memorable, such as terrorism. Stories of terrorism are memorable because they are stories of individuals (sometimes en masse, but individuals all the same). The Environment appears to have no face to it, precisely because it involves every face. When too many people are affected we lose compassion. This is known as psychic numbing.

- Too much information confuses us, leading to inaction or poor choices.

- We remember immediate threats, so that they could be avoided in the future, but we’re constantly on the look out for opportunities (e.g. for pleasure — holidays and air travel).

- Richard Dawkins’ Selfish Gene aside, we only really care about the two generations on either side of us (we can’t care further back than our great-grandparents or further forward than our great-grandchildren).

- The sunk-cost fallacy. We are biased towards staying the course even in the face of negative outcomes. When the world is full of aeroplanes and the economy has been built around aeroplanes, well, we already have them so why not use them?

- Justification. If we all quit holidaying in tourist destinations, entire communities would collapse. We justify our behaviours by focusing on certain details and avoiding others.

- The bystander effect. Most of us are inclined to believe someone else will deal with a crisis. We may expect others to stop traveling on planes, but we ourselves have to. Our travel is necessary; others’ travel is not.

This is infuriating for the relatively few Cassandras out there, trying to persuade others that there is no government conspiracy, and that it is far cheaper to avoid a climate crisis than to try to eke out an existence after ecological collapse.

SETTING OF “IN-FLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT”

“In-flight Entertainment” feels like it’s set in a near future when the world is divided into climate deniers and those who are resigned to it. Alan is accused of having grown up in a gadget-ridden childhood, referring to Gen Z (roughly between the ages of 7 and 22″ in 2019, so younger again at time of publication). Alan is of an age now when he has a wife (Penny) and kids.

Part of me thinks it could easily have been set in 2019, but I don’t think we’re quite at this point yet. Currently the world is divided into four groups:

- Climate crisis deniers

- Those who haven’t given it much thought

- Very worried people e.g. activists

- The tired and resigned

At some point surely categories 2 and 3 will disappear as the realities of climate change make everyone aware of it, and as even the most ardent activists realise the big struggle has been lost. This flight comprises climate crisis deniers and the tired and resigned. In this view of the near future, air travel doesn’t abate one iota.

The story veers backwards into Alan’s on-the-ground life — we learn that there have been apocalyptic protests at Heathrow, that Alan drives a luxury vehicle, that his parents oppose his carbon intensive lifestyle. Alan’s mother has a view on recycling that is stuck in the 1990s — that if we all pull together and make small economies then our collective efforts will save us. This worked for England during the war. The attitude carried us through the 90s, and can be seen in children’s literature designed to encourage recycling, e.g. Just A Dream by Chris Van Allsburg.

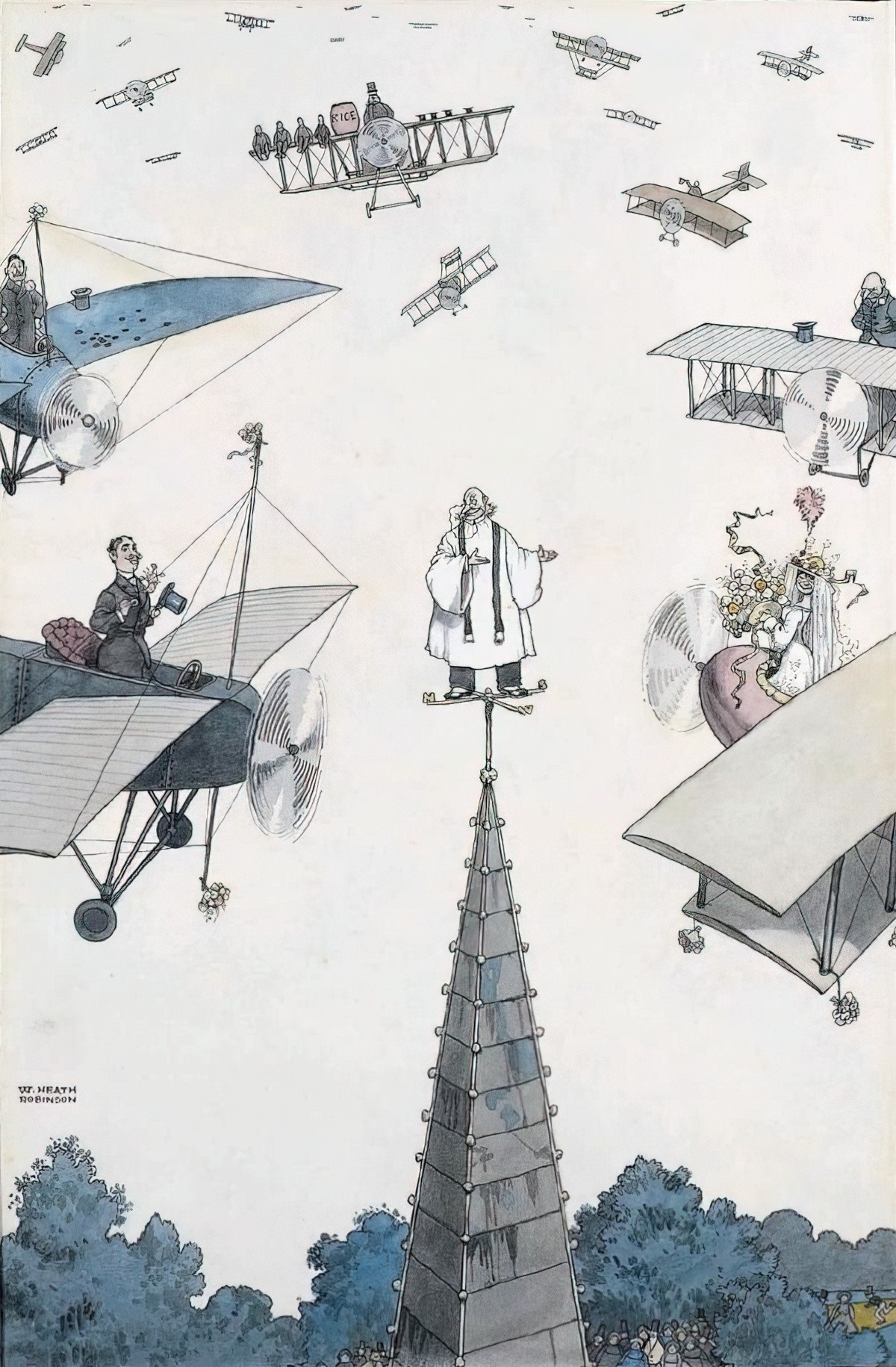

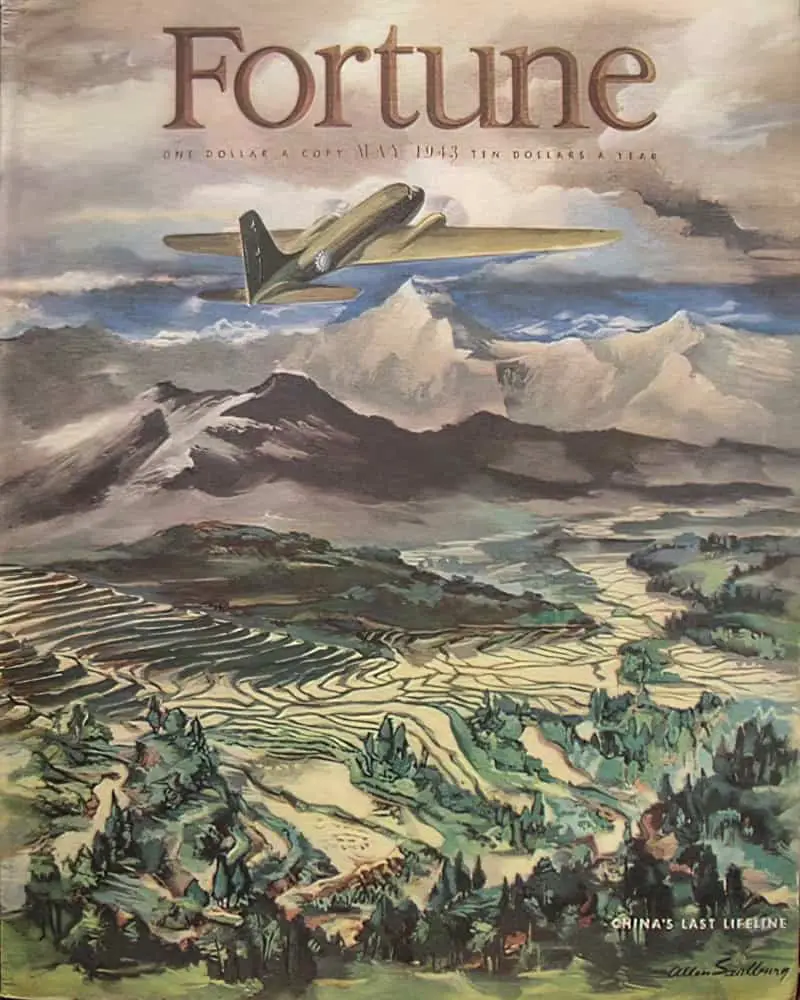

FLIGHT SYMBOLISM

Flight can symbolise various things but most notably it stands for freedom. Air travel is the ultimate luxury, though many of us living in rich countries would no longer call it that — we consider the freedom of flight a birthright. The plane is therefore a perfect setting for this story.

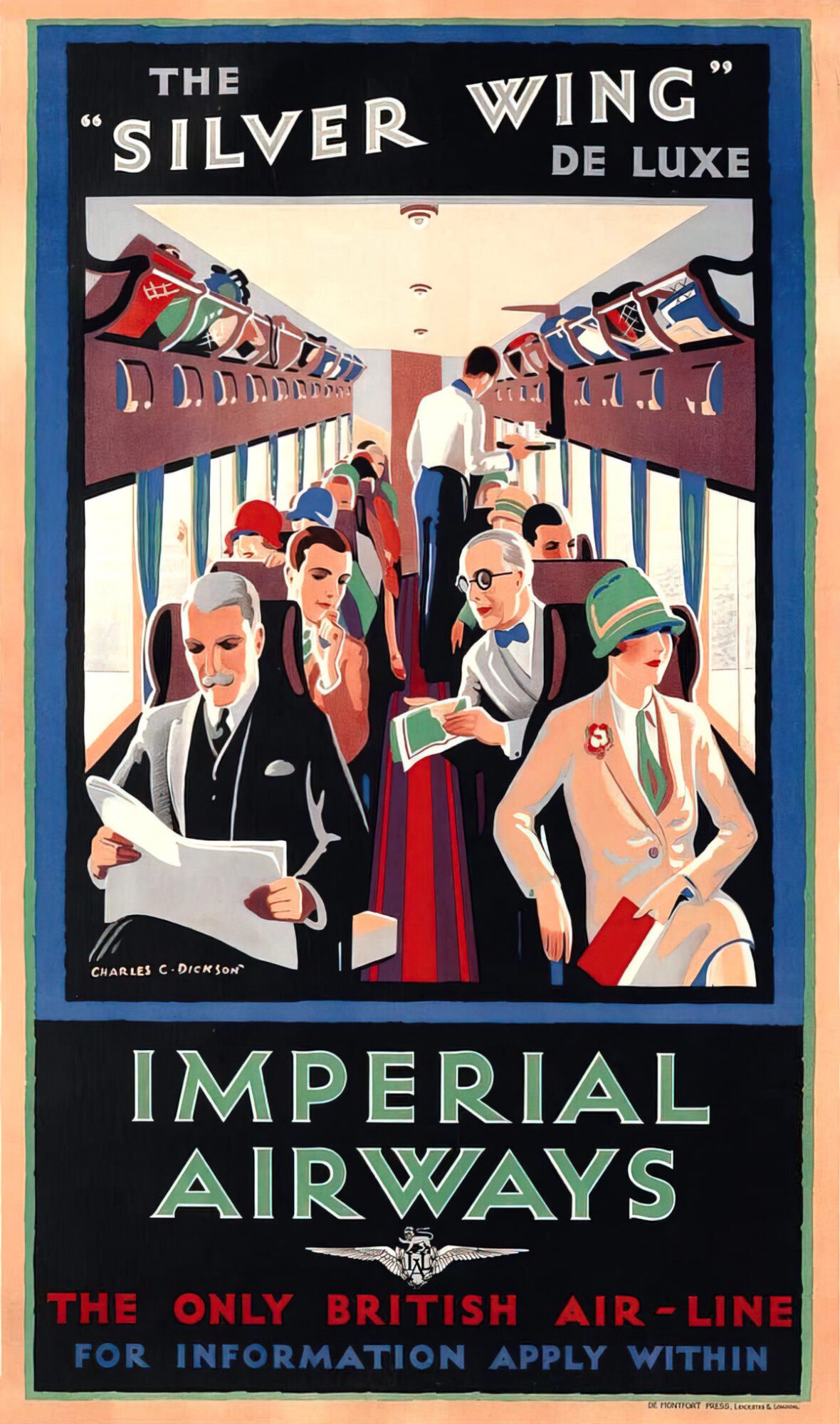

The story opens with description of the different classes of people herded onto a plane — there’s no better reminder than planes of economic hierarchy — First Class at the top (significantly, in Helen Simpson’s story, it’s made up of men), followed by Club Class, Business Class and Economy.

The climate crisis is likewise mostly a class issue, with those at the top using more than their fair share of the environment, symbolised in this story as an extra eight inches of space which ‘makes all the difference’. Difference between what? Is the freedom to fly the difference between a life vs a life worth living?

Helen Simpson inverts the freedom aspect of flight with the intertextual reference to an iconic scene from North by Northwest, in which a man cannot hide from a horrifying crop duster, swooping him like a very big, very dangerous magpie during breeding season. This is the scene Alan watches on the plane when he doesn’t want to hear anything more about climate change.

Within the story there also exists implicit critique of a life lived through screens — we criticise Alan for wanting to watch his old film instead of hearing about the realities of climate change. Soon it is revealed that everything he knows about dying comes via fictional TV shows such as Casualty. This is a guy living in a fantasy world, borne of mindful denial.

GOOSE BAY

The flight is from Heathrow to Chicago. There is a diversion to Goose Bay. Significantly this is close to Greenland, where some of the most obvious impacts of climate change are currently seen. It’s also in the middle of nowhere, like the North by Northwest scene above. The landscape is huge; people are rendered tiny and helpless and all alone. No one is coming to save us from the climate crisis.

So how do the Climate Change Cassandras persuade the deniers? According to this story, it may in fact be impossible.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “IN-FLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT”

Here is the underlying structure of stories with this sort of theme:

- A character encounters another character who tells them something they don’t want to hear.

- Eventually this unwelcome new knowledge becomes too much, so the character hearing the unpleasant thing has some sort of dream/escape sequence.

- When they wake up, they’ve pretty much forgotten the entire interaction.

- Except things will never be quite the same, because they haven’t completely forgotten.

Another outstanding example of a story structured in this way is “Her First Ball” by Katherine Mansfield. In Mansfield’s story, an old man reminds young Leila, fresh to the ball scene, that she will be an old lady soon. This is pretty much the last thing you want to hear at your first ball, so Leila mindfully forgets about the interaction.

SHORTCOMING

This is the story of a community, so no single character stands out as the main one. “In-flight Entertainment” is designed to expose a general human shortcoming — our ability to see the terrible truth then to ignore it.

The cast of characters requires:

- The person who is forced to think deeply about the horrible thing for the first time (for this story it is Alan Barr);

- The person who forces the other to think deeply about the horrible thing for the first time (Jeremy Lees).

Also in this story we have the thread of the old man who dies in his seat. Clearly, someone who dies in our presence is confronting. We are forced to acknowledge the inevitability of death, and we’re reminded that we, too, shall die.

DESIRE

Alan wants to ignore the facts of the climate crisis. He has come up with a reasonable argument which works to this end:

…the science behind these new reports could be quite shaky. There were two sides to every coin, and anyway Planet Earth has a self-regulating mechanism, rather like the economy, and we should leave it to right itself. Mother Nature knows a thing or two…

In this particular story, Alan wants to enjoy his First Class flight to Chicago to give a presentation. The presentation will be delivered in 13 hours’ time — a ticking clock device which plays on the ‘bad luck’ aspect of the number 13.

OPPONENT

Alan, who wants to go on as usual, is in direct opposition to Jeremy, who would have liked the world to change. The ultimate opponent for a climate crisis denier: a climate scientist.

But Helen Simpson then has to explain what the Jeremy is doing aboard an aircraft. This character has reached a point where he has given up trying to change things.

The other opponent is the dead man. His death means they have to stop over and Alan is now in danger of missing his presentation.

PLAN

Everybody’s plan on this flight is to go on as usual. Even while knowing that our behaviours are wrecking the environment, if anything this makes us do more of that exact thing.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle scene is the part where Alan imagines becoming a Doomsday Prepper, with the gun, the barbed wire, the works.

ANAGNORISIS

The tragedy for Alan is that he has no Anagnorisis. He wakes himself up with a snort.

All that alarmist crap that old creep Jeremy had been coming out with, it just seemed like a fairy story now.

To extend the fairy tale connection, Helen Simpson turns Alan into a childlike figure:

In quite a childish way he liked the tiny brightly wrapped bonbons, he liked yawning to pop his ears. Yes, his spirits usually lifted during the descent [HIGHLY SYMBOLIC, OF COURSE], and he would have expected to feel extra-jubilant towards the close of this particular protracted crossing.

NEW SITUATION

Despite trying his best to suppress the information conveyed by Jeremy, Alan doesn’t fully succeed. He is forever changed.

…he had a weight around his heart, a nasty sinking feeling; which was not like him at all.

RESONANCE

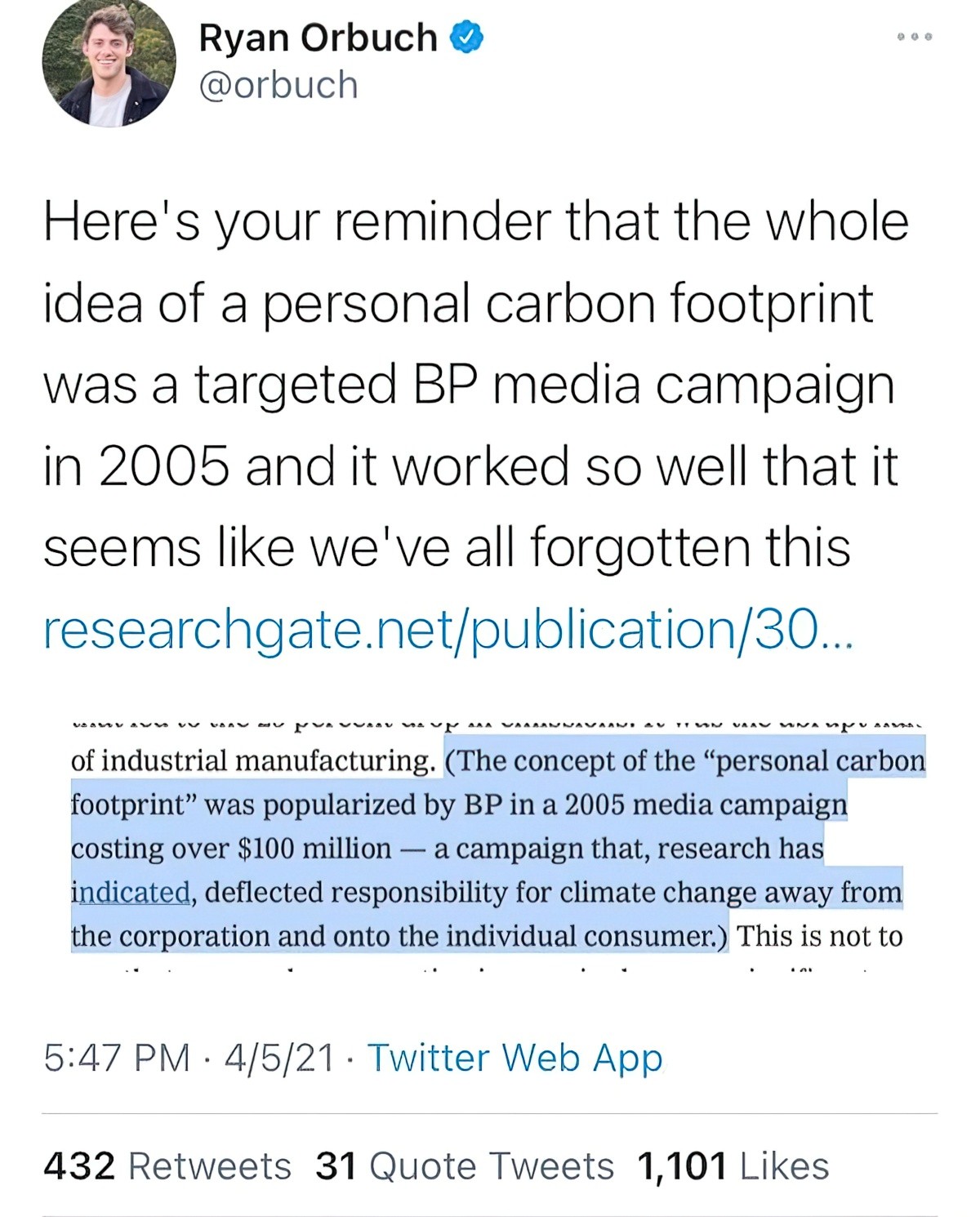

Go back to environmentally conscious picture books from the 1980s and what sticks out is the personal responsibility heaped upon child readers to do small things such as put their own litter in the bin. (This example by Anthony Browne is a good example.)

Just a guess, but Helen Simpson’s In-flight Entertainment will probably look like that in 20 years’ time. We are currently in a moment where individuals are feeling huge pressure to do things such as recycling. We are even starting to shame each other about flying. But we are being hoodwinked. It’s not consumption that’s the main driver of climate change:

Placing 100 percent of the responsibility for emissions on consumers is an ideological trick of market exchange under capitalism. As consumers, we only confront commodities and their prices. We feel free and make choices in this market. Yet what Karl Marx called the fetishism of market relations obscures the social relations of production and exploitation underlying commodities like cars, air flights, and beef. Behind every act of individual consumption are massive corporations seeking and gaining profit from our “choices.”

Rich People Are Fuelling Climate Catastrophe — But Not Mostly Because of Their Consumption BY MATT HUBER at Jacobin

I’m really sorry I caught the ocean on fire by forgetting my reusable grocery bags that one time

@fingerblaster, 10:05 AM · Jul 3, 2021

FURTHER

Interview with Helen Simpson at BBC4 (at about 8:50) and also Margaret Atwood.

The film Melancholia is about depression, but feels to me like it could be about the division between climate crisis deniers and those who know it is coming.

Header photo by Aaron Barnaby