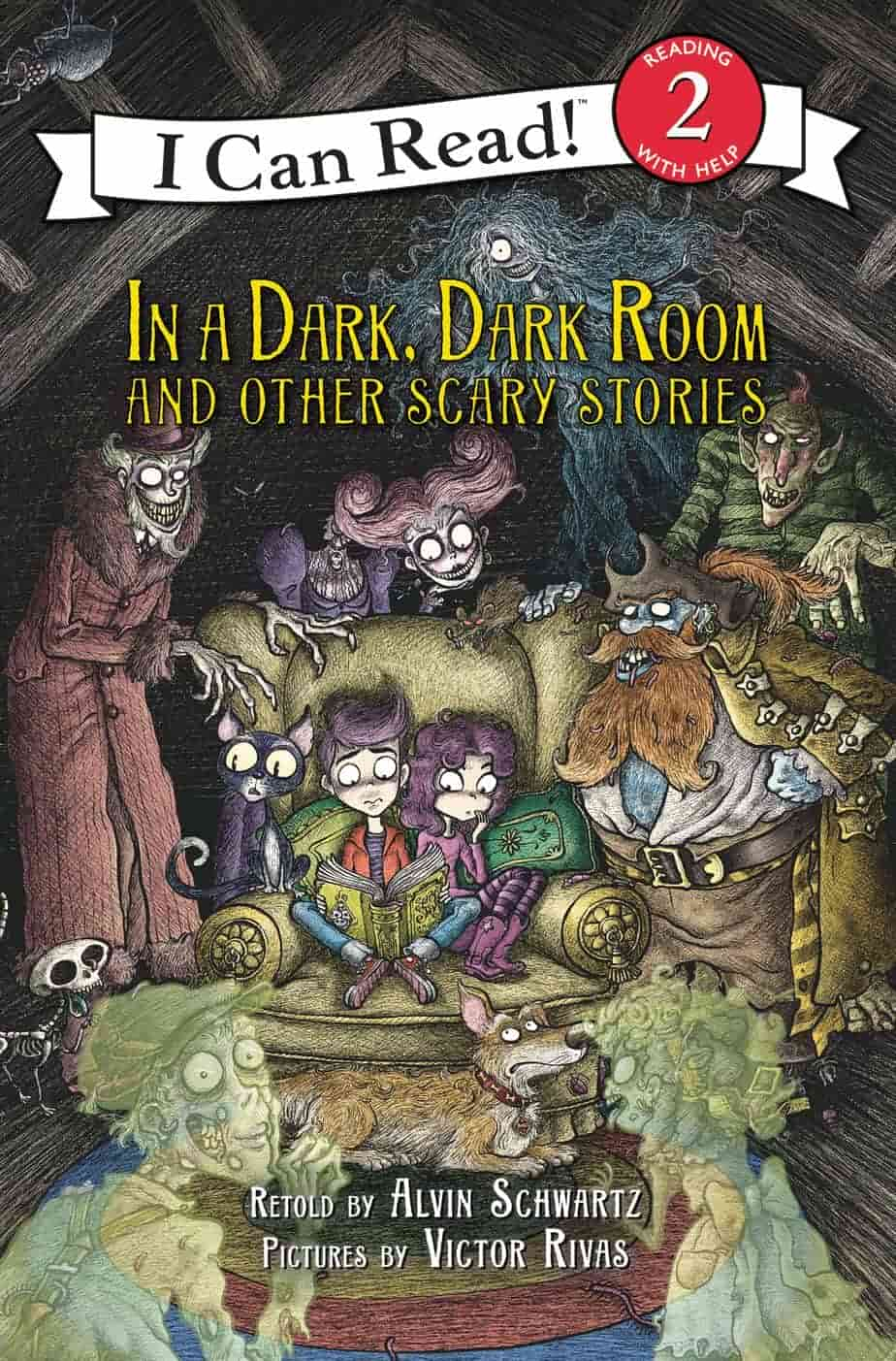

In A Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories written by Alvin Schwartz was first published in 1971 for emergent readers ready for scary… but not too scary. I recently looked closely at a modern picture book called Creepy Carrots, another excellent example of a ‘scary’ story perfectly pitched at 4-6 year olds. This collection is for emergent readers and is a bit more creepy than that. The adult reader is unlikely to be scared by any of these, but many adults today have wonderful memories of A Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories.

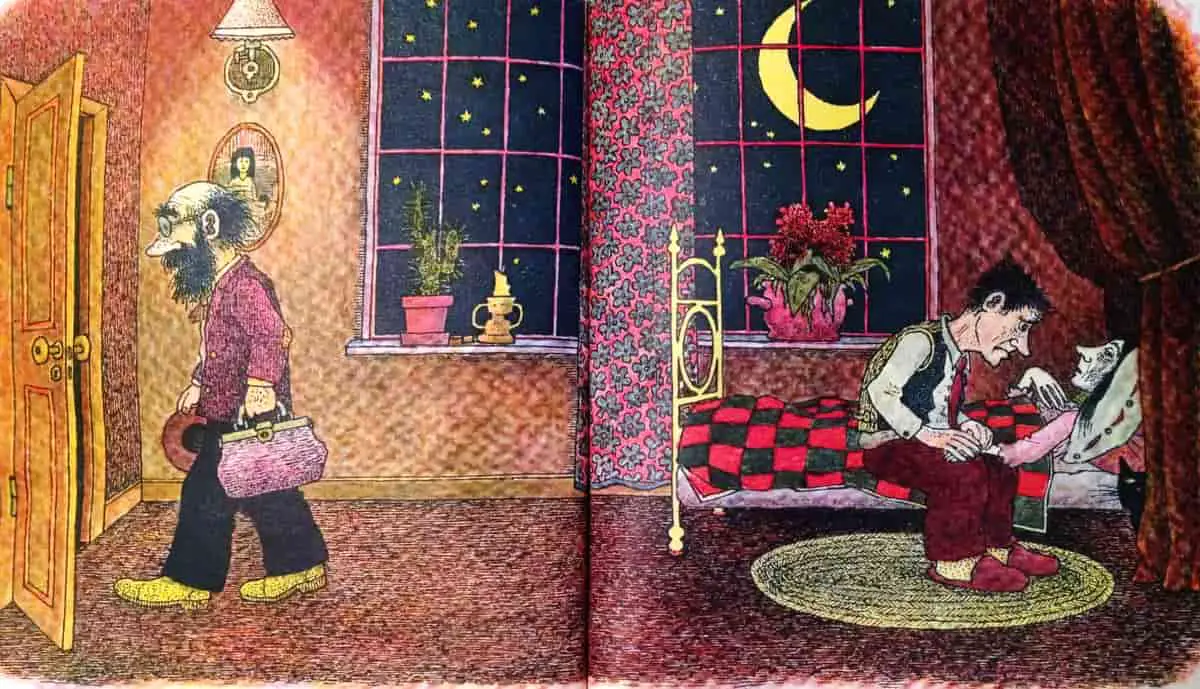

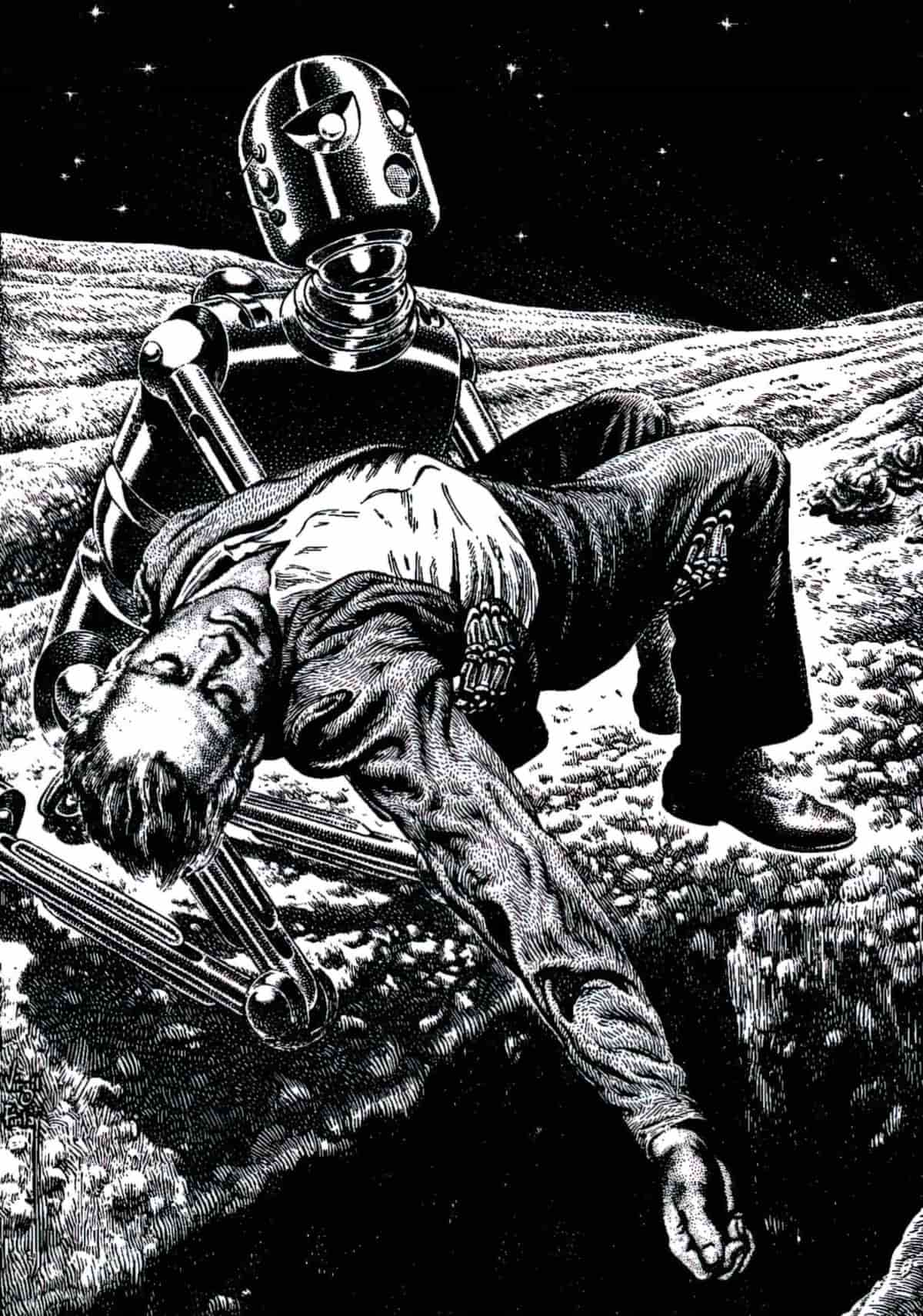

The collection was first illustrated by Dirk Zimmer in a distinctive 1970s style, and more recently by Victor Rivas, who has also illustrated the Ghost Patrol series. Of course one day we’ll look back and this will be a distinctively early 21st century style. Chris Riddell’s work is kinda similar, I think.

Where do these stories come from, and how were they modified for a child audience? The author included end notes which offer a glimpse into the creative process. Basically, Schwartz collected these stories from folklore, so he functions a bit like the Grimm Brothers.

AN EARLIER COLLECTION OF SCARY STORIES FOR KIDS

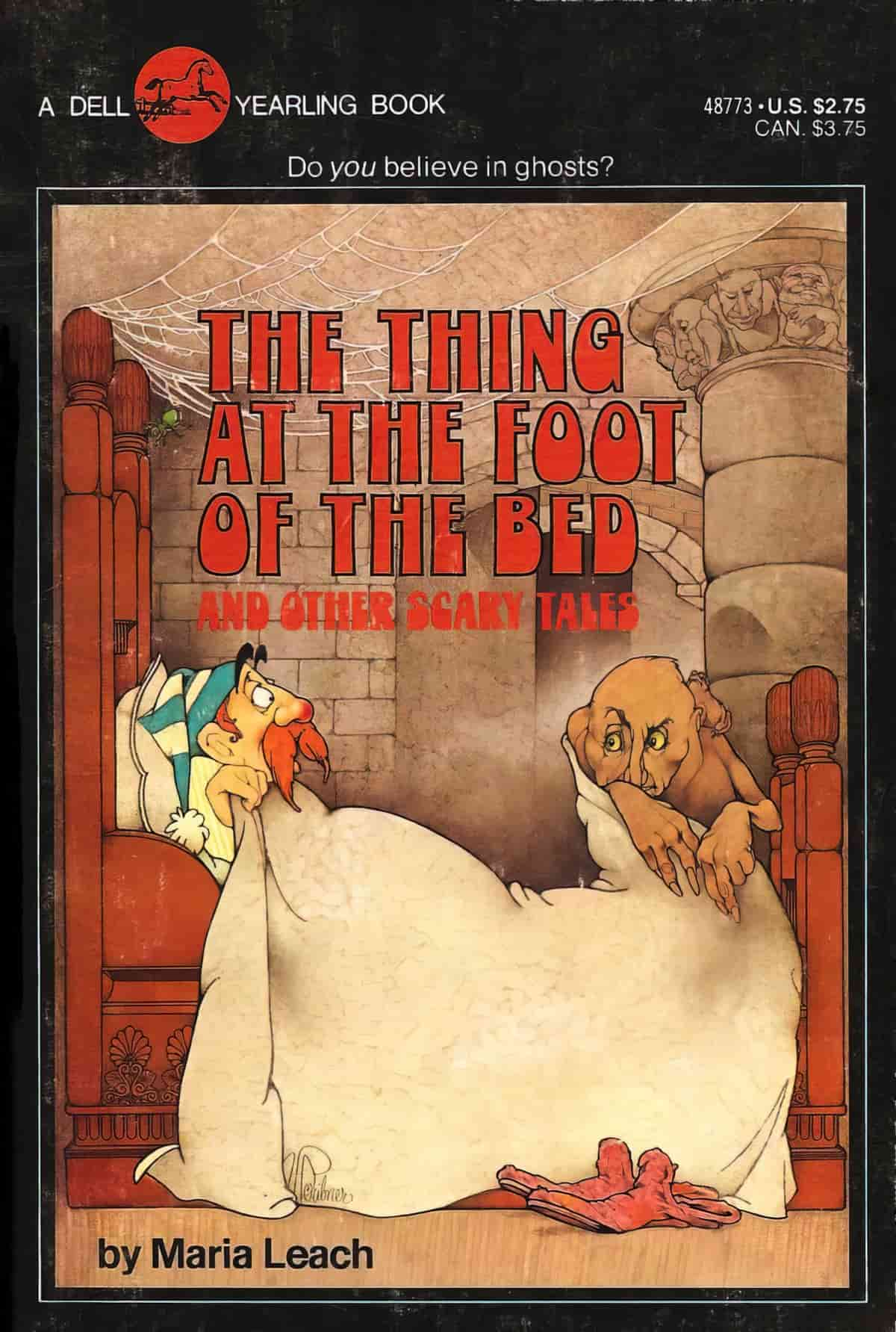

I believe the format and marketing of In A Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories is inspired by the success of an earlier book called The Thing At The Foot Of The Bed (1959, 1987). Both are collections of very short ghost stories aimed at a child audience. Both were very popular with American children. Many adults look back fondly on one or other of these collections. Together they had the second half of the 20th century covered, until R.L. Stine turned up to fill the hole of novel-length scares for the middle childhood set.

THE TEETH

When we grow older, we seem to ‘grow long in the tooth’. In fact, our gums recede. (According to my dentist this starts around forty, though only to the extent a dentist would notice.) What is scary about long teeth? Well, teeth are for chomping and tearing flesh, but whenever something becomes associated with age it also becomes associated with death, so there’s that.

Notes at the end tell us “The Teeth” is based on a story from Surinam, collected in the 1920s.

This classic tale from Surinam was also repurposed as a scary tale for children called “As Long As This”, included in the collection The Thing At The Foot Of The Bed by Maria Leach. First published in 1959, “As Long As This” shows the boy asking for a cigarette instead of for the time. Both collections are aimed at child readers, so this change offers insight into how cigarettes became decreasingly acceptable between the late 1950s and the early 1970s. Leach’s collection was reissued in 1987, probably because adult readers with fond memories wanted to buy the stories for their own children.

See also my (growing) collection of historical tobacco use in illustration (including a lot of illustration for kids).

What I find interesting about this story: It just… ends. The boy is scared by three men, all very scary, and then nothing happens. He just goes home! (I guess.) For older kids, this story might function as a great story starter for a creative writing exercise in the classroom. Get them to finish it off.

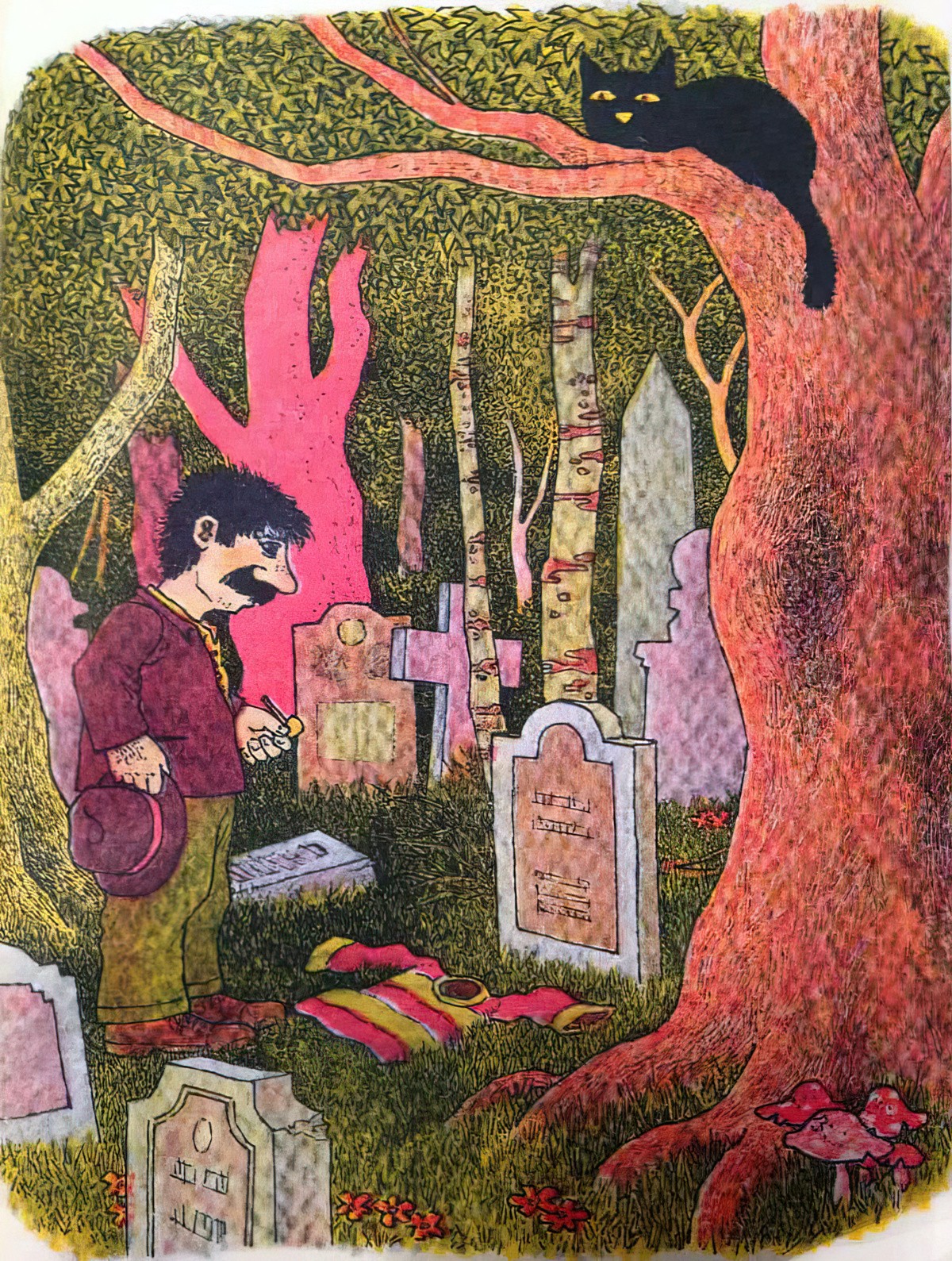

IN THE GRAVEYARD

“In the Graveyard” is a short version of the traditional song “Old Woman All Skin And Bone”.

END NOTES

There was an old woman all skin and bone

Who lived near the graveyard all alone.

O-o-o-o-o-o!

She thought she’d go to church one day

To hear the parson preach and pray.

O-o-o-o- o-o!

And when she came to the church-house stile

She thought she stop and rest awhile.

O-o-o-o-o-o!

She came up to the door

She thought she’d stop and rest some more.

O-o- o-o-o-o!

But when she turned and looked around

She saw a corpse upon the ground.

O-o-o-o-o-o!

From its nose down to its chin

The worms crawled out, and the worms crawled in.

O- o-o-o-o-o!

The woman to the preacher said, “Shall I look like that when I am dead?”

0-o-o-o-o-o!

The preacher to the woman said, ‘You shall look like that when you are dead! ”

“AAAAAAAAAAA!”

The guy in the video below does an excellent job of singing that song.

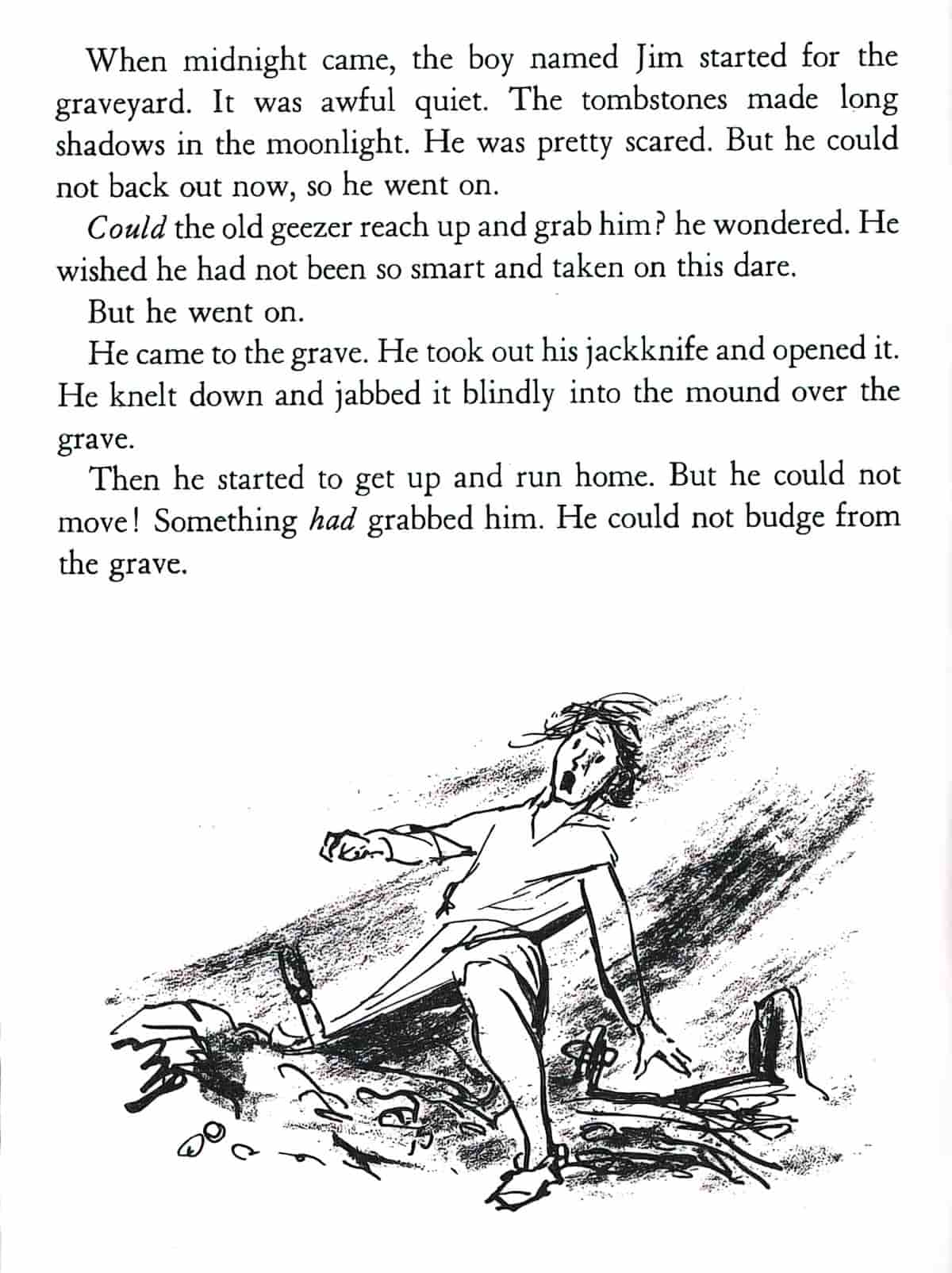

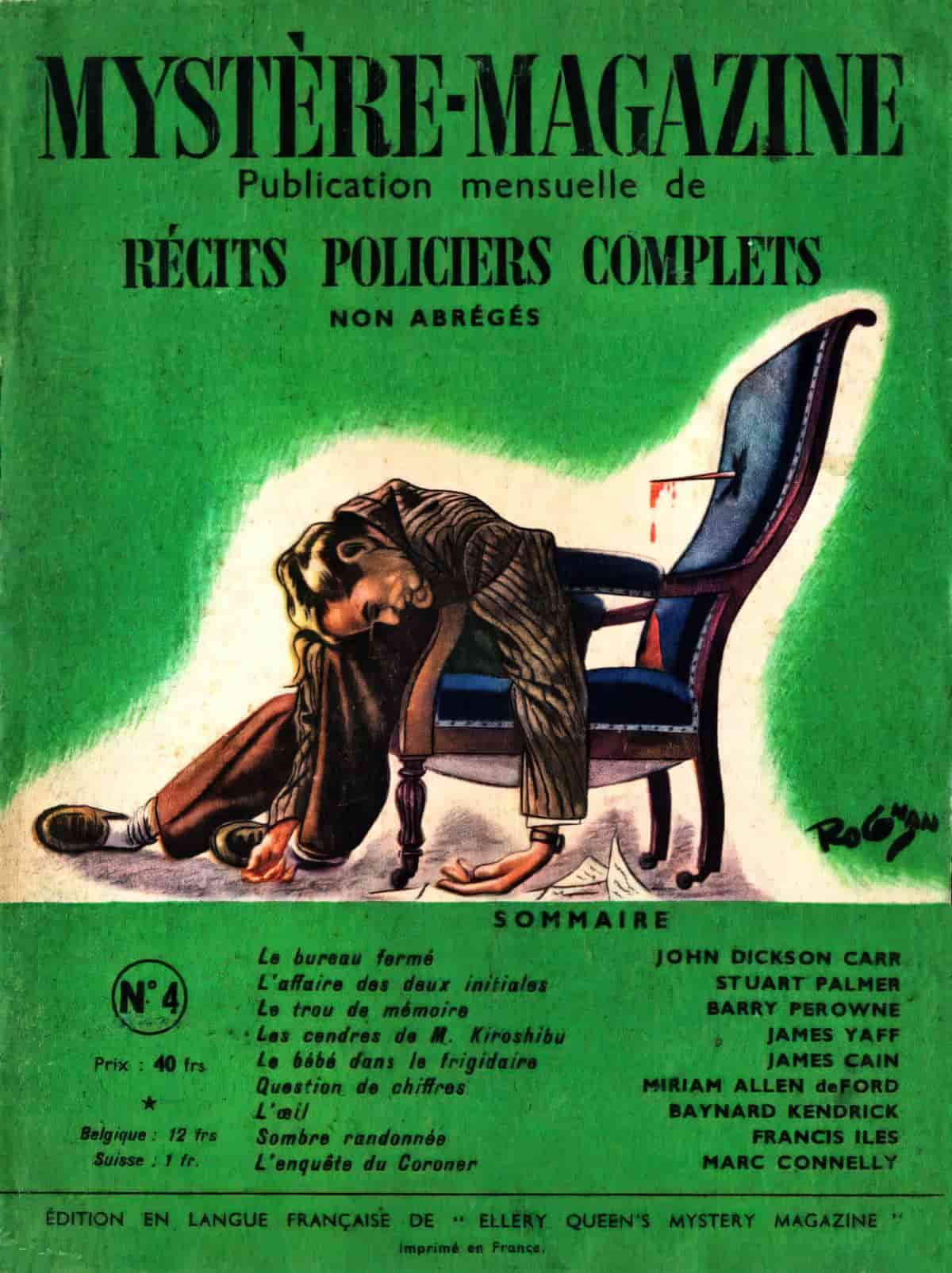

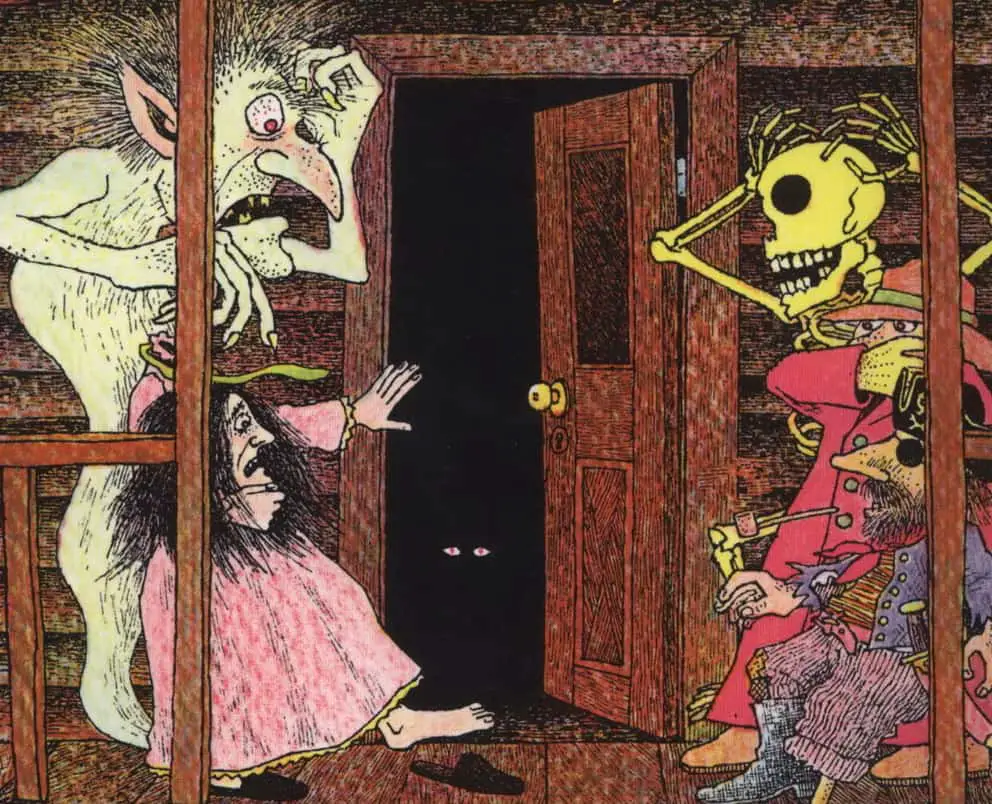

There must be a rule somewhere: Anthologies of scary stories must include at least one story set in a graveyard. Here’s the example from The Thing At The Foot Of The Bed:

That’s not entirely true. The rule goes something more like this: Scary stories must at some point require the audience to consider their own mortality. We more easily consider our own mortality when faced with the reality of a burial site or similar. The woman in this story is scared of the dead men precisely because she links their deaths to her own. Children have to learn that we all die someday. Later, sometime in our teens or twenties we reach the next developmental stage, which Heidegger called ‘Being-toward-death‘ — realising at a gut level that our lives are finite, that although people die, that does in fact include ourselves and we are not invincible.

This collection is aimed at an audience who is still coming to terms with the fact that all people die. It is enough to be confronted by someone else’s death rather than one’s own.

THE GREEN RIBBON

“The Green Ribbon” is based on a European folk motif in which a red thread is worn around a person’s neck. The thread marks the place where the thread was cut off, then reattached.

END NOTES

A man marries a woman and they live a long life together. The man keeps pestering the woman: Why does she always wear that ribbon around her neck? The woman refuses to tell him.

Finally, the woman’s head falls right off.

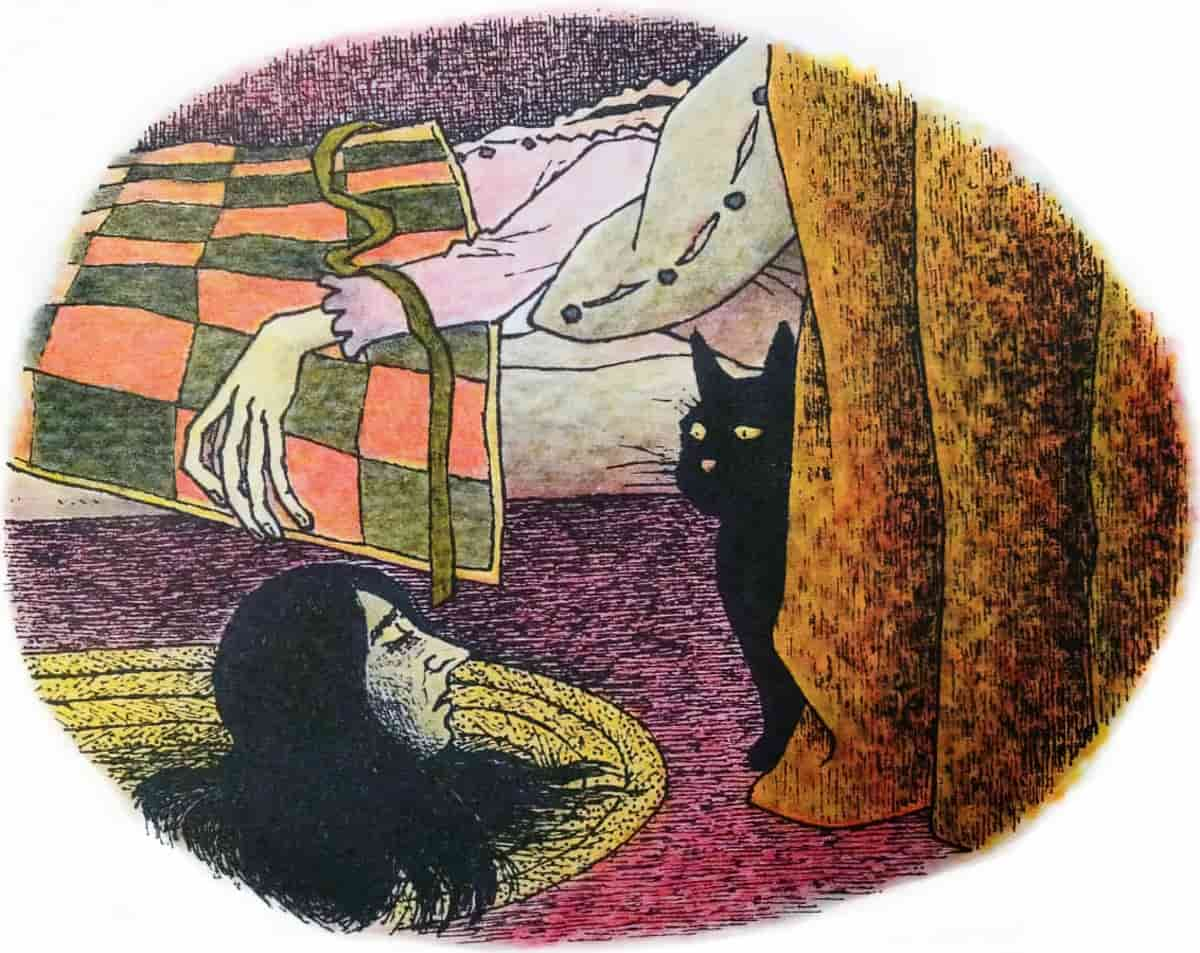

Why is it that artists so often depict (or describe) a character with one arm hanging off the bed? I’m honestly surprised TV Tropes doesn’t have an entry on that. How many people sleep with one arm hanging off the bed compared to how often we see it in art with a melodramatic vibe? Not many, I expect. You’d wake yourself up with a dead arm after a while.

I suspect the arm hanging off the bed serves to emphasise the death-adjacent nature of sleep. (A working theory.) Below is another example, this time from Sleeping Beauty, in which sleep is a kind of death:

And finally the tentpole example of arm hanging off the bed:

Fuseli influenced Gothic storytellers of the early industrial capitalist era, and this imagery has become a Gothic trope.

There is a marvellous contemporary short story called “The Husband Stitch” by Carmen Maria Machado which makes use of this same motif. You can read it for free at Granta. That one’s definitely not for children.

A decade after publishing In A Dark, Dark Room, Schwartz published another famous trilogy of scary stories for kids called Scary Stories To Tell In The Dark.

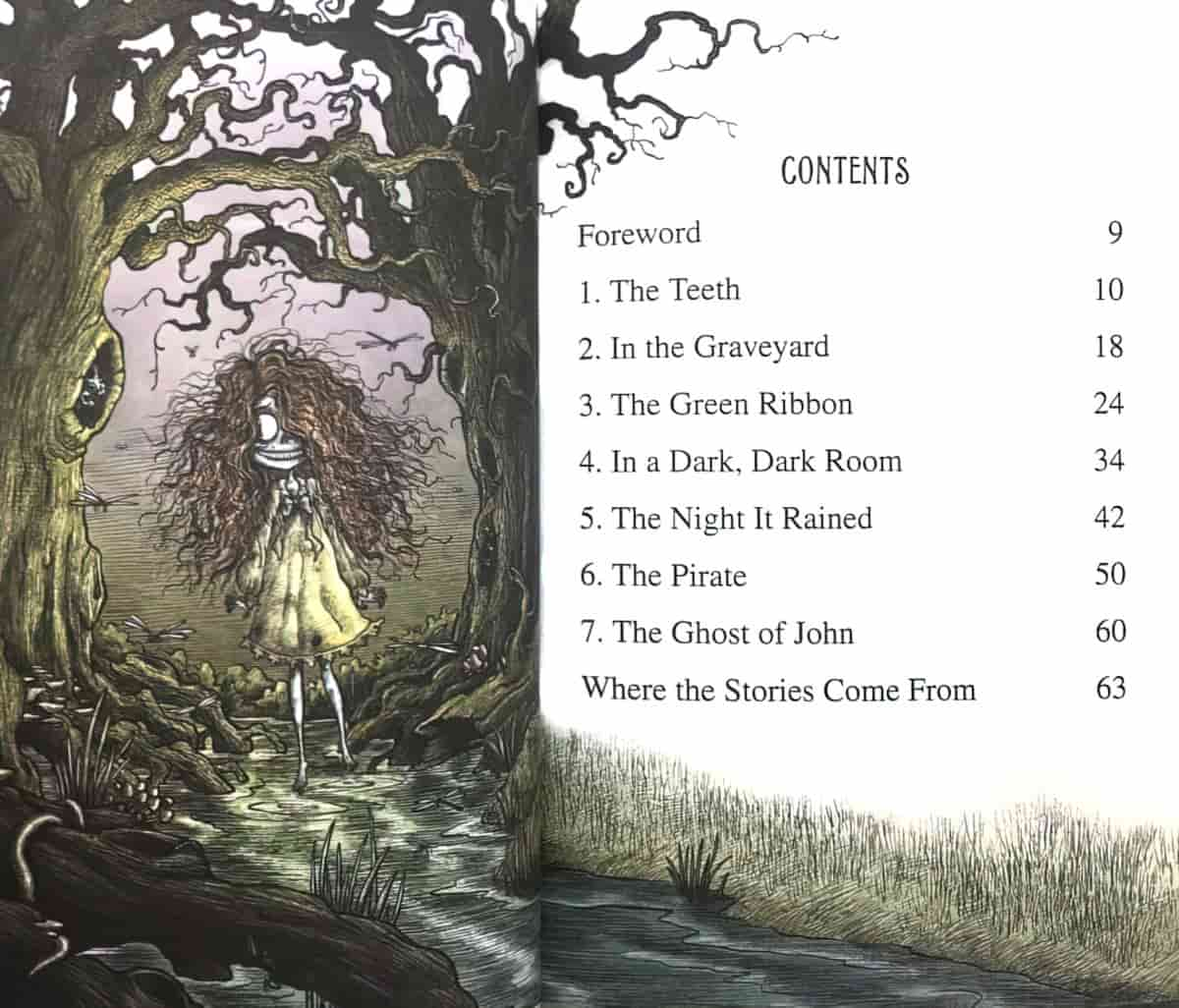

I was delighted to learn subsequently that Machado was influenced by “The Green Ribbon” as written by Schwartz when coming up with “The Husband Stitch”, which goes to show how ancient folk motifs can make their way to contemporary creators via “children’s” literature. I don’t think the writer below realises “The Green Ribbon” was included in Schwartz’s earlier In A Dark, Dark Room, not in his subsequent Scary Stories trilogy. (Find the table of contents here), but this is where I learned Machado was influenced by Schwartz:

When Carmen Maria Machado was preparing to publish her first book, Her Body and Other Parties—a story collection that would go on to be nominated for a National Book Award in 2017—she urged her publisher to hire the reclusive illustrator Stephen Gammell to provide art for the cover. Asked why, Machado pointed to Gammell’s most famous work: the images he provided for Alvin Schwartz’s 1981 kids’ classic, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, and the two sequels that followed. “Every American person between 25 and 40 knows those illustrations and those books,” she said. “They were that iconic and that pervasive.” Gammell didn’t take the job, but one of the stories in Her Body and Other Parties, “The Husband Stitch,” is an eerie, feminist urban-legend fantasia built around a retelling of one of Schwartz’s stories that has haunted Machado since childhood—”The Green Ribbon.” It’s about a man who discovers that his lovely bride doesn’t want him to touch her velvet choker because her head falls off without it.

The Long, Spooky Life of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, Slate

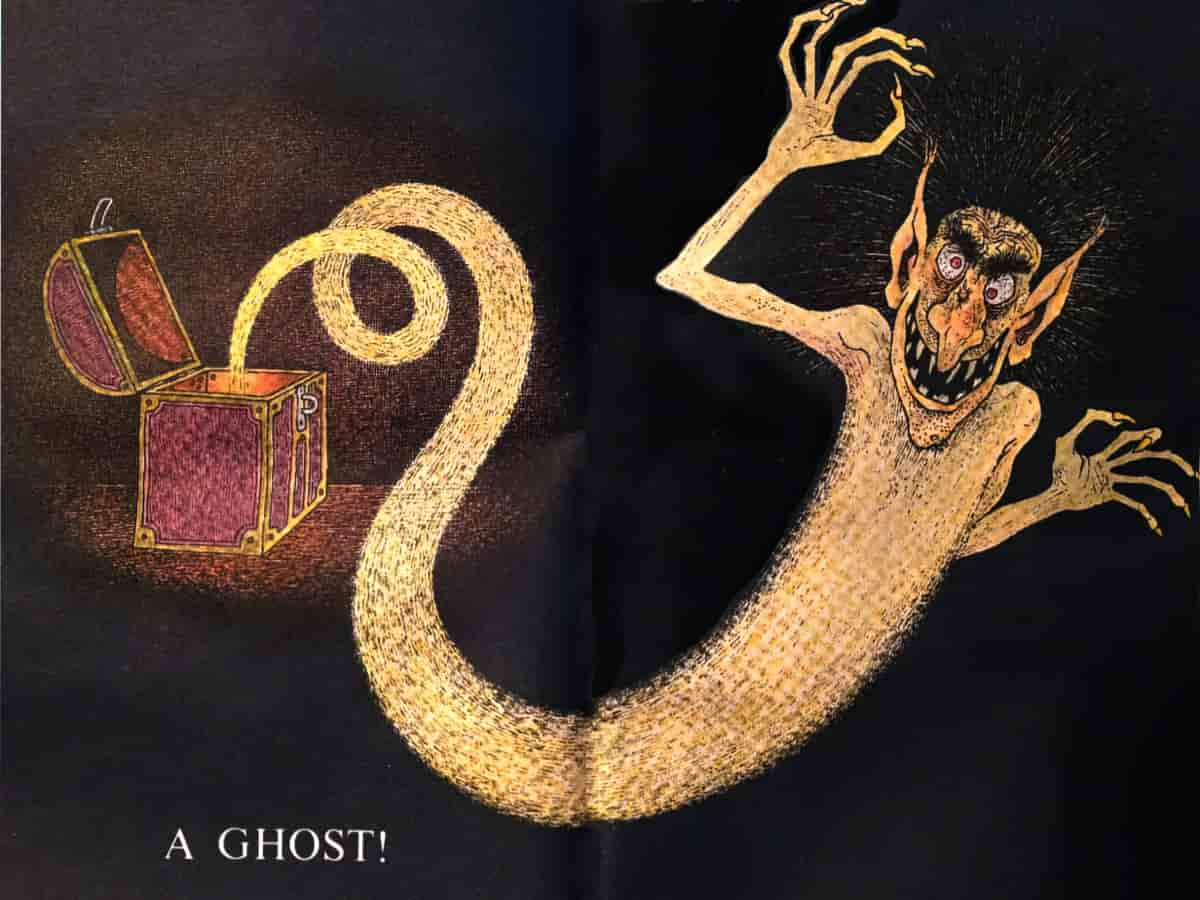

IN A DARK, DARK ROOM

The end notes tell us this oral game is known in England and America. I call it an ‘oral game’ because words are used to build up to a jump scare. Certain fairy tales achieve the same frisson, notably Little Red Riding Hood. When Little Red Riding Hood queries the wolf in grandmother’s bonnet, the reader knows what’s coming. The narrator’s job is to act out the part where the wolf eats up the little girl, and hopefully the narratees are delighted by this performance.

Stories which work around this jump scare mechanism actually improve upon retelling, precisely because the young audience knows what’s coming.

The ghost coming out of a box scare never gets old.

There’s a well-established fine line between horror and comedy. Perhaps Rowan Atkinson took this well-known story and turned it into something like this: “It’s like the story of the blind man, looking for the black cat, in the dark room. Which isn’t there.” (It’s all in the delivery.) Atkinson was probably riffing on these famous analogies, known as The Black Cat Analogy. This is used to try to explain the difference between science and religion.

That’s not what the scary story is about, but when all examples are considered together, humans clearly have an affinity for thinking about dark things inside dark things in a mise en abyme kind of way. Darkness scares us. How do you make a dark thing even more scary? Position it inside another dark thing…

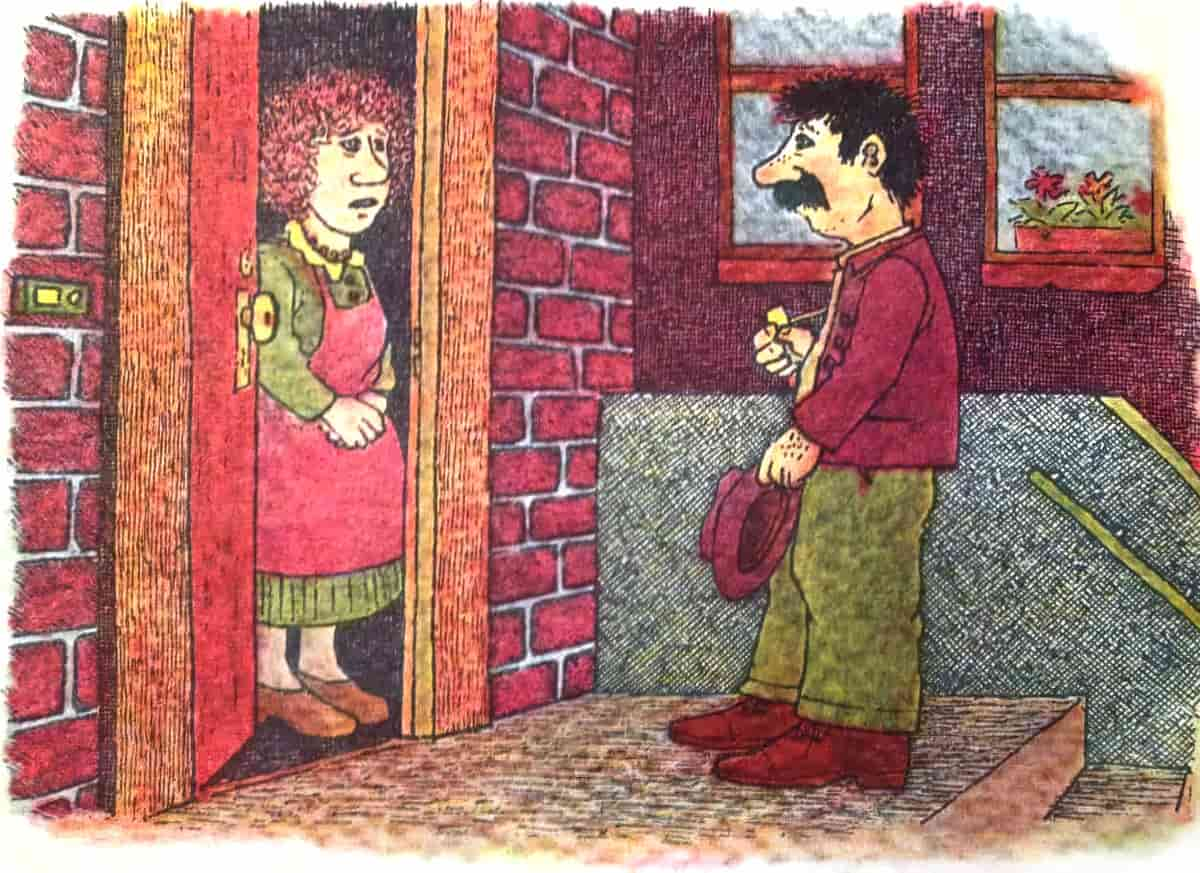

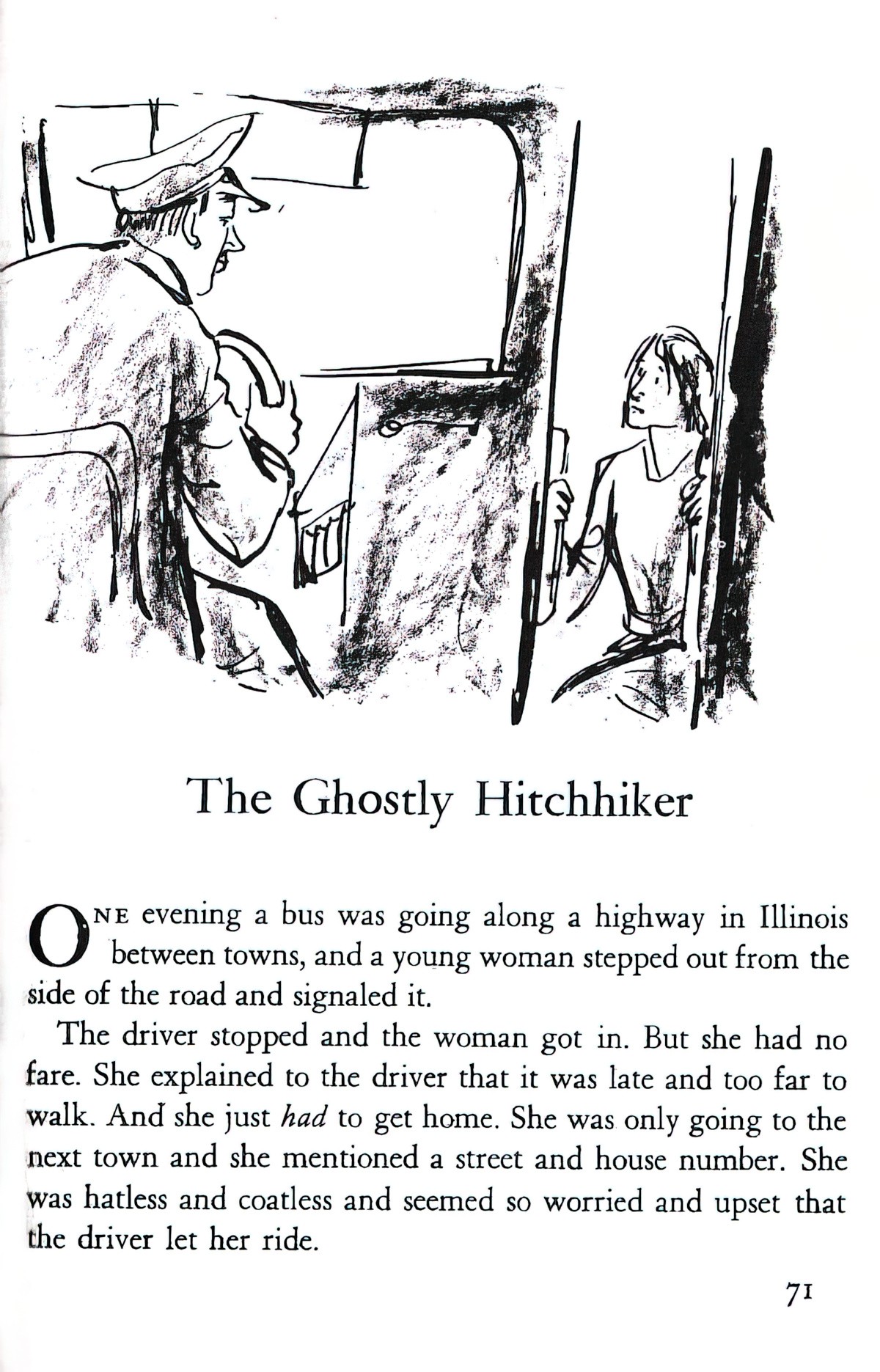

THE NIGHT IT RAINED

There are many scary stories about drivers stopping to pick up hitchhikers. (I’ve written one myself: How To Leave A Stranger)

“The Night It Rained” is a kid version. Contemporary kids have all been told not to accept rides with strangers. If your kids are like mine, they’ll probably comment on that. I think even in the 1970s, kids were urged to avoid accepting lifts from strangers, so I don’t accept this as an example of the story having dated; I think Schwartz was well aware of this. As it happens, the man who offers the ghost boy a lift is a good guy.

It’s interesting to find a hitchhiker horror included in a children’s collection because I feel you have to be old enough to drive to fully appreciate the scariness of seeing someone on the road in poor conditions and realise you’re utterly responsible for not killing that person.

For the same reason, I’m fascinated by The Stranger by Chris Van Allsburg, a picture book ostensibly for children but which plays with my deep-seated fear of accidentally killing someone with my car. Likewise, children have yet to experience the specifically adult moral dilemma of whether or not to stop and help someone else’s kid who appears to be in a bit of trouble. (The dilemma is heightened for men, I expect.)

Commonly, the human main character is left wondering if they’ve just experienced something supernatural, and their suspicion is confirmed when they find ‘proof’ in the form of a real-world object which has crossed the border from the supernatural world.

The gravesite is coded as a liminal space, as academics might say.

This motif is used in picture books also. A child has a fantasy experience (it’s usually fantasy rather than supernatural) and returns home. The parents know nothing about this and the reader is left wondering if we’re supposed to code that experience as pure fantasy on the part of the child. Then the child finds something from the fantasy world, a signal to the reader that within the veridical world of the story, it really happened.

An example is The Polar Express, again by Chris Van Allsburgh, which the boy finds in his pocket. (There are ideological issues with white boys taking ‘souvenirs’ from the places they visit… I’ve written about that here.)

Hitchhiker stories are commonly included in anthologies of scary stories, including in stories for kids. The private vehicle is considered a private space, and accepting someone into your car is kind of like accepting someone into your bedroom. In the mid 20th century, cars broke down a whole lot more than they do today, and there were many more hitchhikers on the road as a result — the vast majority of them decent people whose cars had simply let them down.

Now that cars have become so reliable, the hitchhiker on the highway is a scarier prospect, so I doubt the hitchhiking horror stories are going anywhere soon. It would be interesting to see how hitchhiker stories changed if families gave up private vehicle ownership and instead hooked into a common network of always-on-the-road sharerides, optimised for the lowest possible miles by sophisticated algorithms. We might then expect to be consistently sharing rides with strangers.

Technology could get us there right now, but we can’t just erase 70-80 years of horror stories about rideshares, the success of Uber notwithstanding.

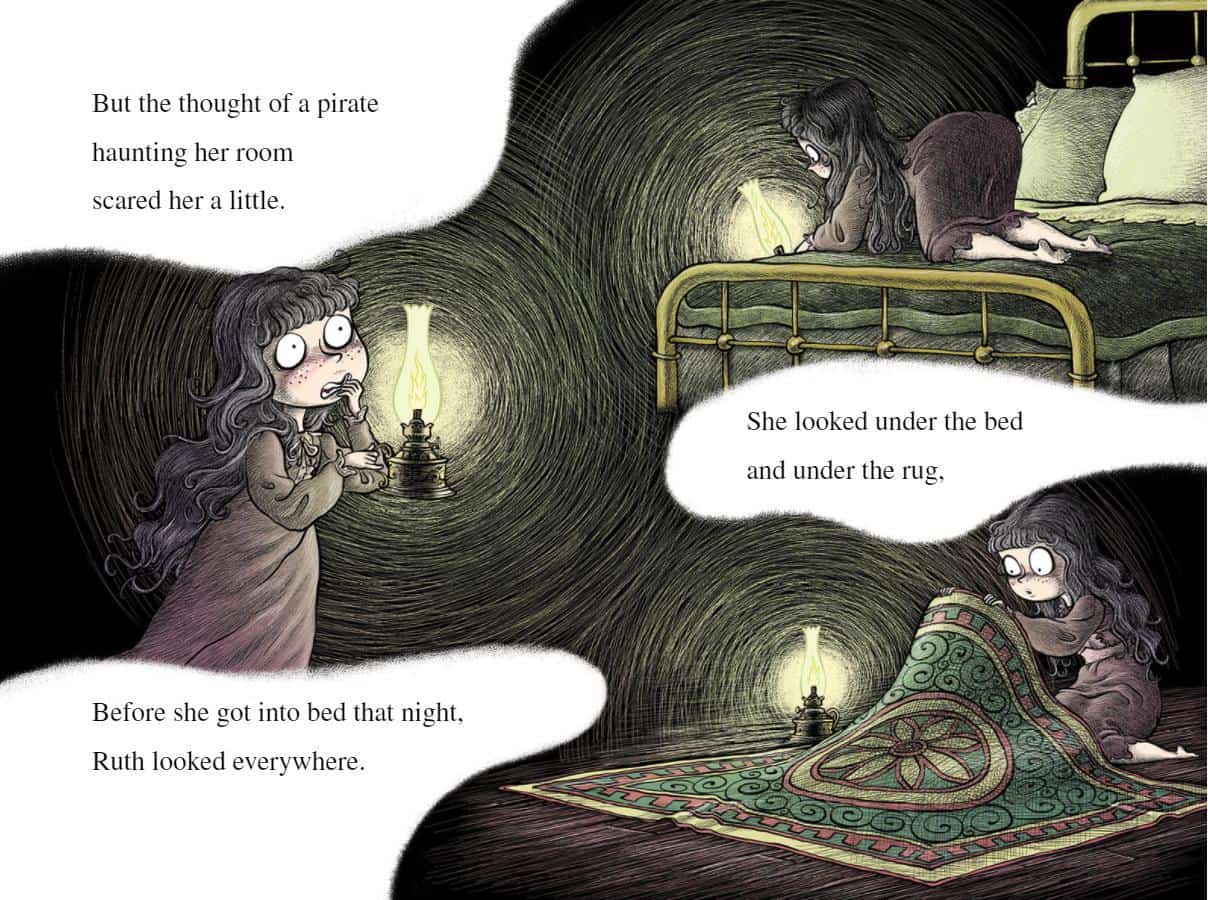

THE PIRATE

A girl goes to stay with a friend, who tells her the room she’s about to stay in is haunted by the ghost of a pirate. Neither girl believes in ghosts.

“The Pirate” is based on a reference in A Dictionary of British Folk Tales in the English Language by Katherine M. Briggs, v. 3. p. 416.

END NOTES

(This dictionary was published across four volumes in 1970-1. Unfortunately I don’t have access to it right now.)

Although the girl doesn’t believe in ghosts she searches for it anyway, in the drawers, in all the nooks and crannies. (This frantic searching for ghosts is also utilised in Creepy Carrots.) At last satisfied that there is no ghost, she lies down to sleep and says, “Just as I thought. There’s just me.”

“And me!” a voice booms back. The story ends here. We never get to see the identity of the ghost. What’s left off the page can be more scary than what’s on it. This trick from cosmic horror will leave young readers imagining their own ghost.

It’s one thing to see a ghost; it’s another for the ghost to invade two senses: hearing AND seeing. The character who first sees a ghost then hears it is a common escalation in ghost stories, and stories tend to finish right after the character has heard the ghost. We now know they’re doomed. Whatever the ghost decides to do, there’s no comeback. Might as well end on that note, right?

THE GHOST OF JOHN

“The Ghost of John” was collected by the compiler in 1979 from Lynette M. Lee, age 8, Stockton, California.

END NOTES

My kid queried the choice to depict the ghost as a skeleton, which reminded me that the current generation of children aren’t entirely used to ghosts depicted as skeletal. If you look at death a depicted in art from 100 years ago and prior, skeletons were commonly used for this purpose, but today the ghost tends to be white, semi-opaque and floaty, perhaps involving a sheet.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen discuss In A Dark, Dark Room on episode #73 of The Yarn, School Library Journal’s podcast about children’s books. They acknowledge its influence and discuss how children are exposed to many scary things in other areas of life (e.g. visiting an art gallery) but in children’s literature gatekeepers avoid giving them exactly what they crave. They also talk about how certain fairytale motifs, such as being eaten alive, aren’t genuinely scary. In this case because there’s this idea that whoever’s been eaten is still safe inside the baddie’s belly and can still be rescued. This pertains to “The Green Ribbon”, in which the woman’s head falls off. If this happened in real life it’d be truly terrifying, but it’s not actually that terrifying in a scary story because there’s this idea that if it was held on all this time by a ribbon, we can fix it in the same way.

Australian and New Zealand kids weren’t as well served with the creepy stories for kids, until R.L. Stine became internationally popular. At around that same era we enjoyed the short story collections of our homegrown Paul Jennings. Kids today are spoilt for choice with their scary stories, although some have been ‘de-scarified’. A child reader who’d like to get a hold of the Scary Stories To Tell In The Dark trilogy may have a hard time sourcing the editions illustrated by the wonderful Stephen Gammell, deemed too scary by some, and re-released in 2010, this time with illustrations by Brett Helquist. This has happened before. The original illustrator of Roald Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes was considered too scary when paired up with Dahl, and Revolting Rhymes was subsequently illustrated by Quentin Blake — a much longer partnership. The Horrible Histories books are part of this same tradition, and recently turned 25 years old, according to the cover of my kid’s latest Book Club gift.