The United States has always been a terrible place to be sick and disabled. Ableism is baked into our myths of bootstrapping and self-reliance, in which health is virtue and illness is degeneracy.

Madeline Miller

Illness, disability and disfigurement has a problematic history in children’s literature. What are the main problems, today and in the past, and how might writers aspire to do better?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE AND ILLNESS

When you think of classic children’s literature and illness, you’re likely to come up with The Secret Garden.

The Secret Garden […] presents ideas that could certainly be called subversive, since at the time they were new and of dubious reputation. In this case, however, they are ideas about religion, psychology, and health. Colin’s self-hypnotic chanting recalls the sermons of Christian Science or New Thought, in both of which Mrs. Burnett [the author] was interested. The idea that illness is often largely psychological, and can be cured by positive thinking, permeates [The Secret Garden]. Another new concept is that of the healing power of nature, of fresh air and outdoor exercise. Today we take ideas like this for granted, but Mrs. Burnett grew up in an age when the only exercise permitted to middle-class women was going for walks. The Secret Garden also shows the influence of the new paganism that found a following among liberal intellectuals of the time. It contains a kind of nature spirit in Dickon, the farm boy who spends whole days on the moors talking to plants and animals and who is a sort of cross between Kipling’s Mowgli and the many adult incarnations of the rural [man-beast god] Pan who appear in Edwardian fiction.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grownups: The subversive power of children’s literature

The Secret Garden is a typical example of literature from the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, which from 1850 until the first world war.

Now we are in the Third Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Children’s stories have never been so accomplished or diverse. Still, there have been expressions of concern lately about the amount of ill-health in contemporary children’s literature. Ill-health is one of modern children’s literature’s defining features.

Author Philip Womack and his fellow judges read 60 books to come up with the shortlist for the Branford Boase award, which rewards children’s authors at the start of their careers and has honoured names from Meg Rosoff to Mal Peet in the past. According to Womack, at least a third of the submissions this year had a “very similar narrative: there’s an ill child at home, who notices something odd, and is probably imagining it, but not telling the reader. They’re all in the first person, all in the present tense, all of a type,” he said.

[…]

“Children’s adventure it seems has become internal, the setting no longer the outside world but frequently the family, with narrative tension and action arising from issues such as mental health and individual trauma,” [Julie Eccleshare] said.

[…]

For Womack, small-scale dramas, focusing on illness or disability, can be done well – he pointed to titles including Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, and RJ Palacio’s Wonder – but “in order to write this kind of narrative you need to be very skilful and I just think the problem is that publishers and authors maybe imagine that if you give a character an illness, they will be sympathetic”.

Domestic Dramas Crowding Out Adventure Stories Warn Children’s Book Prize Judges, The Guardian

It’d be easy to assume, then, that there’s one clean trajectory threading the history of children’s literature, starting at healthy and robust, moving to physically ill, to mentally ill, to so protected and cosseted in cotton wool that it’s impossible to get injured, but inevitable to suffer mentally. Or, the main character is literally dead, narrating from beyond the grave. The Lovely Bones type narratives are the epitome of illness, in a way.

But the history of illness in fiction doesn’t look like that at all.

Christopher Robin Had

A.A.Milne

wheezles And sneezles,

They bundled him Into His bed.

They gave him what goes

With a cold in the nose,

And some more for a cold

In the head.

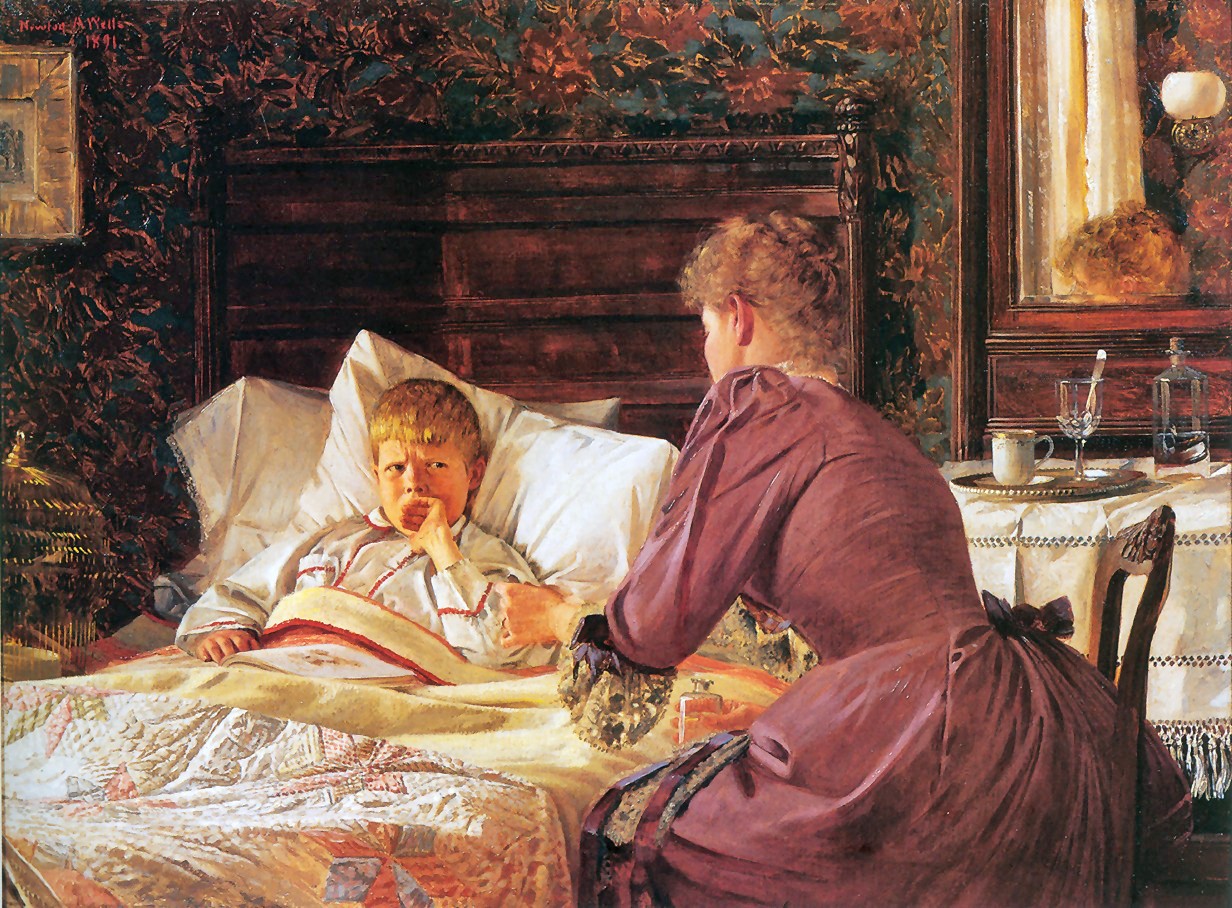

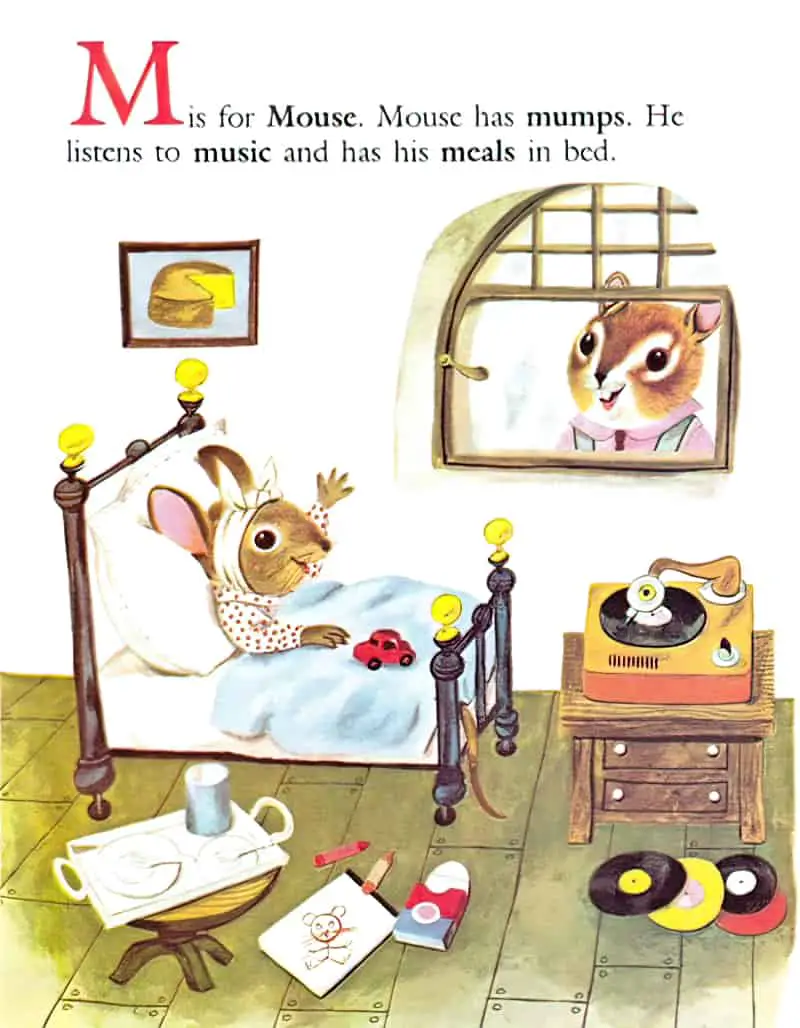

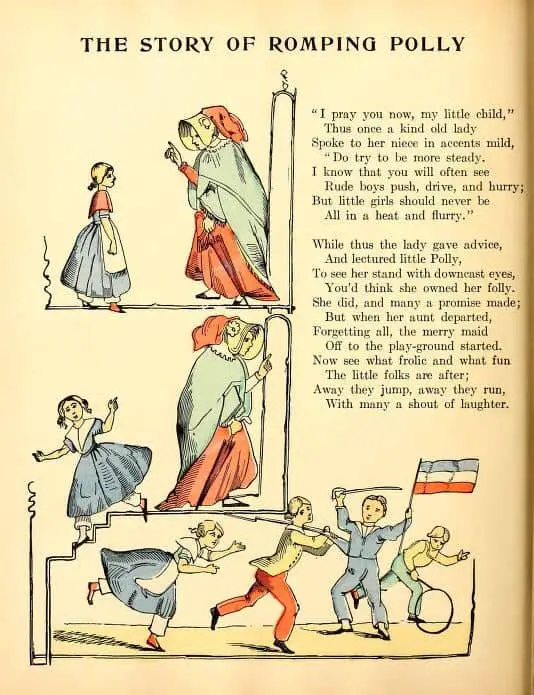

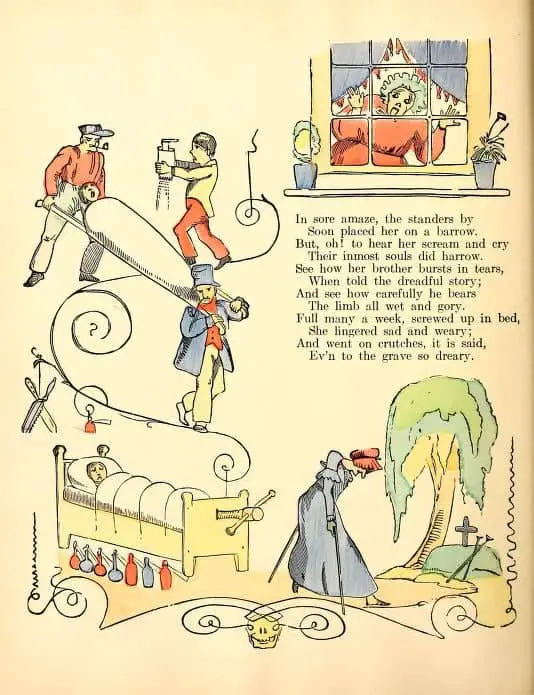

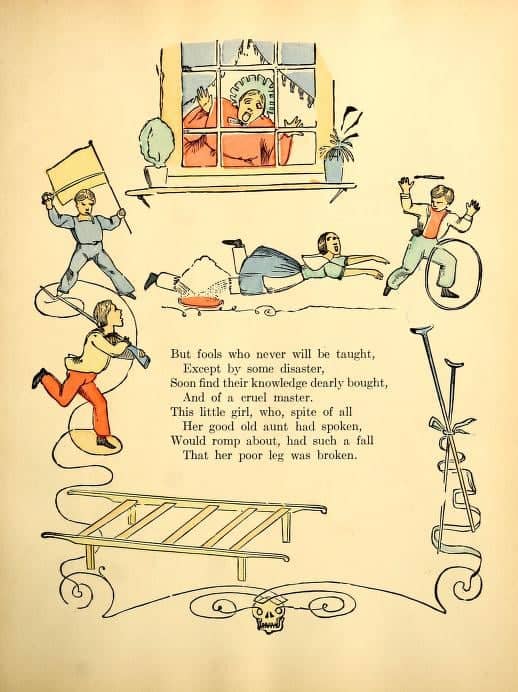

Why do we see more illustrations of children in bed, or wrapped up, in earlier ages? After finding this in a ‘humorous’ book of cautionary tales for children, I feel these images of laid-up children looking sad are partly to warn children off dangerous forms of play.

I also wonder if the contemporary absence of convalescing children is because our modern culture no longer remembers the concept of convalescence.

Ill-health in storytelling goes back to oral folktales. The Grimm Brothers produced seven different collections of tales. The final (considered definitive) was specifically designed to sell to families with children, and for that volume the Grimm Brothers fleshed out the oral tales they collected, adding their own puritanical Christian and misogynistic morals. But the two eldest Grimm brothers started off as pure collectors, and it was only in 2014 that Jack Zipes published his translations of that first, unadulterated collection of oral fairy tales into English. In the preface, Zipes writes:

The tales of the first edition are often about “wounded” young people, and many of them were told to illustrate ongoing conflicts that continue to exist in our present day. For instance, the tales frequently depict the disputes that young protagonists have with their parents; children brutally treated and abandoned: soldiers in need: young women persecuted; sibling rivalry; exploitation and oppression of young people; dangerous predators; spiteful kings and queens abusing their power; and Death punishing greedy people and rewarding a virtuous boy.

Zipes emphasises that these tales existed for several hundred years before the Grimm Brothers collected them. He’s also keen to remind us that these tales weren’t originally designed for children. They can’t really be considered children’s literature, partly because there was no clear delineation between the concept of adult and child. Zipes makes a link between ‘wounded’ and the ‘underdog’ as archetype:

Throughout the tales of the first edition, there is what I call an ‘underdog’ perspective. That is, there is almost always a clear hostility toward abusive kings, cannibals, witches, giants, and nasty people and animals. There is always a clear sympathy for innocent and simple-minded protagonists, male and female, little people, and helpless but courageous animals. Kings often renege on their promises or abuse and exploit their subjects, including their daughters, and they are either exposed, dethroned, or killed.

Even in modern storytelling, audiences have a strong preference for the underdog. In fact, one of the best ways to get an audience to side with a villain (antihero) is to show him (or rarely, her) in a vulnerable, low-status or put-upon position during the set-up. We see it in Breaking Bad, when Walter is sprung washing cars by his high school students. We see it in The Sopranos, when Tony does procures a CD player for his old mother who treats him like dirt.

This leads into reasons why stories about sick main characters are popular, and why writers might make use of illness to explore various ideas about the human experience. Let’s look at some case studies.

Cancer: The Fault In Our Stars

Despite the tumor-shrinking medical miracle that has bought her a few years, Hazel has never been anything but terminal, her final chapter inscribed upon diagnosis. But when a gorgeous plot twist named Augustus Waters suddenly appears at Cancer Kid Support Group, Hazel’s story is about to be completely rewritten.

Marketing copy for The Fault In Our Stars

The blockbuster contemporary sick-lit YA novel is of course by John Green. Published 2012, The Fault In Our Stars has since been made into a film. Green took a few years between that and his next book, which is not about cancer but about mental ill-health, based on his own experiences with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

When one partner of a love story has a major illness, this is a legitimate and believable way to keep to love opponents apart. This is increasingly more difficult to do as a writer of love stories, because in our more free Western culture it’s fine to get together with the person you love, without a novel-length amount of longing and lust. That alone would be a bad reason to write terminally ill characters. Writing about cancer might be a way for teens with cancer to see a representation of their experiences in fiction — an experience previously ignored, and therefore taboo.

There’s another big reason which may account for the popularity of The Fault In Our Stars. As Nicole Galante argues in her paper “A Genre Against Them: Regulating Young Adults Through Literature“, most YA literature affords young people power… if only they are patient (and don’t die). This is a false kind of power, and probably not all that pleasing to read. This tendency accounts for the fact that most YA stories are ‘future-oriented’.

However, stories in which characters have no guaranteed future cannot be future-oriented. The characters must find a way to grasp hold of their power in the here and now. This makes literature about sickness surprisingly fresh.

Popular as it is with its target audience, The Fault In Our Stars did catch a little heat. Some readers felt Green went beyond ‘depiction and representation’ and slipped into ‘glorification’ territory.

Trust me, I understand that the deification of pain and suffering is a longtime feature of fiction. I bring up The Fault in Our Stars because as much as those characters explicitly and repeatedly speak angrily of people who idealize death, the text itself idealizes death; that book is widely beloved. The idea that suffering distills us down to something pure is an old and lauded trope of Western fiction.

It’s just a super shitty one.

Deborah, Dreamwidth

Mental Illness: Am I Normal Yet?

Green’s Turtles All The Way Down is not the only blockbuster book about OCD. The following year gave us Am I Normal Yet? by Holly Bourne.

All Evie wants is to be normal. She’s almost off her meds and at a new college where no one knows her as the girl-who-went-crazy. She’s even going to parties and making friends. There’s only one thing left to tick off her list… But relationships are messy – especially relationships with teenage guys. They can make any girl feel like they’re going mad. And if Evie can’t even tell her new friends Amber and Lottie the truth about herself, how will she cope when she falls in love?

Marketing copy for Am I Normal Yet?

It’s interesting that the marketing copy says nothing about the main problem in the book — Evie is living with OCD. This is kept as an early reveal. Am I Normal Yet? is a popular YA novel and the first in a series known as The Spinster Club. The narrative is surprisingly didactic at times, launching into Tumblr-like tirades on issues such as the casual flinging about of terms like ‘OCD’ and ‘panic attack’ when the speaker has no idea what these conditions really mean for people living with them. As per the marketing copy, this is mostly a story about a young woman who is delving into dating, a bit later than her peers, due to her early teenage years being filled up with the nothingness and imprisonment of OCD. Like various other stories (The Sopranos, Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You, Big Little Lies), sessions with the therapist provide further insight into the main character’s head, even though it’s written in first person. Such self-examination in someone so young would otherwise seem unrealistic.

Plot-wise, Evie’s OCD depicts an exaggerated response to the normal (but healthy) anxiety shared by all young people as they enter the dating world. Strangely, I was reminded of Diary of a Wimpy Kid when reading this. Greg Heffley is younger of course, and prepubertal. (My favourite word. Go on, say it aloud.) Greg is disgusted by adult bodies, which comes to the fore (in sometimes sexist and fatphobic ways) as he visits the local pool, for instance. In this young adult novel Evie is older in years, but still having trouble reconciling the admixture of emotions around finding sex and romance appealing, yet repulsive. Evie’s OCD shines a light on something common to many — the unaroused state of looking in at romance and thinking it’s totally gross and crazy, versus the state of arousal and attraction, in which all of those feelings (normally, ideally) go straight out the window. In short, the main character’s OCD examines a common disconnect around romantic love and the dirtiness of sex.

Memory Loss: The Secret History Of Us

There is a subcategory of young adult novels which star young women who have lost their memory. The memory loss might be due to an accident, or there might be science fiction/paranormal/crime elements. She gradually recovers her memory over the course of the story. This is a subcategory of the amnesia story — a narrative device which allows reader and main character to discover the setting together, creating extra empathy for the main character.

I’m searching for the chosen one/long-lost princess/heroine, who disappeared as a baby. I’m definitely not going to check orphanages for pretty teenage girls who have suspiciously specific amnesia.

@Brooding YA Hero

EXAMPLES

In 2008 we got The Adoration of Jenna Fox by Mary E. Pearson. Set in near-future America, seventeen year old Jenna awakes from a coma after a terrible accident. Memories slowly return as she watches movies of her life. It reads as a teen medical drama.

In 2011 we got The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer by Michelle Hodgkin. Mara wakes up in a hospital with no memories of how she got there. She can’t remember the accident that killed her friends. She has PTSD and her family is concerned for her mental health. (Unlike many paranormal young adult stories, Mara has a family who cares about her.)

In 2014 we got Don’t Look Back by Jennifer L. Armentrout, about a young woman whose best friend has gone missing. Sam herself wakes up with no memories. The facts of Cassie’s disappearance are buried deep inside Sam’s memory.

2017 gave us The Secret Memory Of Us, whose plot looks very much like a newer version of The Adoration of Jenna Fox.

Olivia wakes up to realize she doesn’t remember. Not just the accident—but anything from the last four years. Not high school. Not Matt, the guy who is apparently her boyfriend. Not the reason she and Jules are no longer friends. Nothing. That’s when it hits her—the accident may not have taken her life, but it took something just as vital: her memory. The harder she tires to remember things, the foggier everything gets, and figuring out who she is feels impossible when everyone keeps telling her who she was. But then there’s Walker. The guy who saved her. The one who broke her ribs pumping life back into her lungs. The hardened boy who keeps his distance despite Olivia’s attempts to thank him. With her feelings growing for Walker, tensions rising with Matt, and secrets she can’t help but feel are being kept from her, Olivia must find her place in a life she doesn’t even remember living.

Marketing copy of The Secret History Of Us by Jessi Kirby

The ur-story of the ‘female led love story with memory loss’ is Sleeping Beauty. When the young woman remembers nothing of her past, authors have a lot of storytelling techniques at their disposal:

- The female main character can undergo a sexual awakening, even if she’s had one before. We tend to romanticise our first sexual experiences, replaying them over and over in our minds. In The Secret Memory Of Us, Olivia gets to experience her first kiss with a boyfriend she has had for a while, and therefore safe with. In the story, she’s literally redoing her first kiss. To the young reader, this feels cosy and safe.

- The female main character is at a permanent disadvantage. The boys around her — namely, her love interests, her brothers, everyone — knows more than she does. This allows the writer (and readers) to indulge in the helpless girl fantasy, in which adolescent girls are saved by more mature, competent boys. This is a common and enduring fantasy. The wide appeal of the Twilight books stand as evidence of that.

- But if the female main character is passive through no fault of her own — e.g. a car accident — the author can also depict her as a ‘strong character’ with plenty of agency. Unlike Bella Swan, Olivia can’t be described as passive. The main character of a memory loss story can be really quite proactive in reclaiming her memories, piecing clues together with the singular focus of a detective. In other words, the memory loss plot allows an author to create a young woman who is both helpless and proactive at the same time.

SICKNESS AND GENDER

Writing at Bitch Media, Alana Kumbler noticed a commonality in YA stories about sickness:

A girl is forced to face the reality of her illness, engages in recovery through her ambivalent relationships with other sick teens, and ultimately figures out how to “come out” to the “normal” kids and gain acceptance even though she’s marked as different.

Kumbler also noticed some problems. One is to do with the cover art:

They [girls depicted on the covers] are unmarked by their illnesses, so there’s no physical difference to bar identification between healthy reader and ill character. The covers, then render illness invisible while simultaneously reinforcing our cultural imagination of tragically beautiful illness as the province of vulnerable white female bodies.

Another problem is to do with the accidental enforcement of the rules of femininity:

Illness novels (like other YA novels for girls) emphasize the importance of protocols of femininity, which must be followed regardless of whether one is sick or well. In McDaniel’s Six Months to Live(1985), for example, the central characters do each other’s makeup while in the hospital.

Another problem is in line with the point Barbara Ehrenreich made in her book about relentless and unhelpful positivity, Smile Or Die:

[The sick teenage girl is] urged to fight cancer through “imaging” techniques

Separately, the patriarchal nature of the medical system generally goes unchallenged and unexamined.

Kumbler lists some character tropes common to illness YA:

- main characters defined by fashion choices, extracurricular activities, hair type, and parental occupation

- the cute and charming terminally ill child

- the amputee/cancer survivor potential boyfriend

- the strong, attentive older brother

- the “normal” guy at school who serves as crush object but is often a jerk

- the father who can’t accept his daughter’s illness

- hospital staff with accents or personality quirks (an Irish brogue, a tendency toward clumsiness, extreme perkiness)

And describes a common plot:

- Typically, mysterious symptoms lead to diagnosis

- Which leads to denial and angst

- Which ultimately leads to either acceptance and cure or acceptance and death.

- Illness is more common than disability, and when there is disability, it’s usually the result of an earlier illness. This is because there’s a lot more potential for drama in a new diagnosis.

- The girl commonly keeps her illness hidden, but is punished when the secret comes out.

SICKNESS ON TV

It’s not just young adult literature which has been including characters with mental illness as part (or main character) in the cast. This is a trend also seen on television.

TV, and comedy especially, has really delved into mental illness recently. What do you think makes that such a prescient topic right now?

It’s funny because it definitely does feel like that’s a thing that’s happening on TV and that we are a part of it. But it was never our intention to really delve into exploring mental illness or different versions of depression or anything like that.

I think we’re just seeing more and more are shows that are allowed to take their characters seriously. I think that’s something BoJack is and I think the fact that you’re seeing more and more shows that are serialised goes hand in hand with that. In the past, a character had a funny quirk, but you couldn’t really delve into that because you had to make every episode make sense on its own. You couldn’t go too dark with it; you had to keep that status quo going for as long as possible.

But now you’re seeing the creators of the show really take those quirks seriously, and the actors can take that seriously and go, ‘Okay, well what does that mean that this character acts this way? Or react to these situations in this manner? Why would his character do that?’ You can keep asking questions and following up on that. These characterisations get richer and deeper and more deeply felt.

If you look at the last 60 years of television, I think you’d actually see a lot of characters that exhibit the symptoms, perhaps, of the kind of thing you see now. The only difference is now you can really unpack that and we’re given the space and the interest to really explore those things and take them seriously — and take the characters seriously.

Junkee

RELATED

Tuned In: ‘BoJack Horseman’ Is A Surprisingly Honest And Insightful Look At Depression

PROBLEMATIC DISABILITY NARRATIVES

To summarise:

- It’s possible the balance of sickness and illness is pushing out adventure stories, but is publishing a zero sum game? If there’s a problem, could it be publishers are promoting domestic dramas more than they’re promoting adventure stories? So, a problem with marketing? Or is it readers themselves who are leading the charge here?

- In representing serious illness such as cancer, and combining them with love stories, lightening the tone, are authors accidentally glorifying those very illnesses they’re hoping to realistically depict?

- In a memory loss love story, does the proactivity of the female character in regaining her memory and solving the mystery really compensate for her inherent passivity? Related: If a young reader enjoys ‘female passivity’ fantasies, is that going to cross over into her real life, causing problems in relationships?

- In medical dramas which give a lot of information about the illnesses and symptoms, the descriptions can border on the grotesque, turning the story into a gross-out experience. An injection can almost seem titillating.

- By focusing heavily on a character’s illness, the author is setting the character up as separate from the reader. There’s a risk the author will end up making the reader feel like a caring person with a character arc which starts off invoking reader repulsion for reader pity.

- Sick characters can position the character as a source of inspiration for non-sick readers. Perversely, sick characters can be set up as someone to idolize because of their illness. Idolisation doesn’t equal social acceptance or recognition.

- A new diagnosis allows dramatic potential in loss of social status, beauty and romantic potential, as if it’s impossible to be ill as well as have social status, beauty and romantic potential.

- In stories where a girl is punished for ever having kept her illness hidden, this is a clear message that it’s wrong to keep your own medical details to yourself. (This actually reminds me of some problems with the current #MeToo movement, in which authors writing about any sort of identity must come out publicly in order to be accepted as a legitimate voice.)

- Teen illness stories are rarely narrated by the sick girl herself. First person narration via healthy best friend or sister has traditionally been a common viewpoint. In Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, the story is narrated by a boy who lives nearby. The Fault In Our Stars may have marked an abrupt shift in how illnesses are depicted in young adult fiction. Green’s book is narrated by Hazel herself, which avoids all sorts of problems (mentioned above). Namely, if the girl dies at the end (or even if she doesn’t) the person who undergoes the character arc is the bystander, not the girl herself. Like the titular Million Dollar Baby, the sick/disabled girl is the sacrificial lamb for the (more important) bystander.

Disability And Disfigurement As Moral Problems

Disfigurement is a separate issue from disability, but worth a mention.

Disability and disfigurement aren’t the same thing, though of course a person can have both. Disability is about what a person can or can’t do (or the fact that society says they can’t, or doesn’t set them accessible paths); disfigurement is about how a person’s body appears.

But disfigurement, specifically, is alive and well in children’s literature — often used oppressively by the narrative. It’s often a symbol of evil, or a punishment, or something negative, or something meaningful on moral levels, as something for a character to “overcome.” It’s almost never simply a way that bodies can be. But in real life — like disability, like fatness, like other embodied aspects that literature uses oppressively — disfigurement is simply a way that bodies can be. We need to call out oppressive use of disfigurement in children’s literature. Notice when it’s a symbol. Notice what it’s a symbol of. Notice when it’s a punishment. Talk about it.

Dicey Tillerman

“If you give handicaps & scars to your characters only as a way of marking them as evil, outcasts, tough and manly, or to make them feel exotic/mysterious (aka, to other-ize them), think about what that says to your real-life readers, and then think outside the stereotype box.”

Naomi Hughes on Twitter

See Also

‘Curious affection’ or ‘monstrous affliction’? Revisiting Patricia Piccinini from Overland

TO STRIVE FOR AS WRITERS

- When characters are sick, they need to be the ‘main characters’ of their own stories. Whatever the narrative technique chosen, they should be the ones undergoing the character arc. The safest way to achieve this is to narrate the story via the sick character, not from her sister/boyfriend/neighbourhood boy.

- Descriptions of the medical treatments need to be a careful balance between realistic/informative and grotesque. Ideally, we need #OwnVoices narratives.

- We all know someone with illness. We’ll all lose health at some point. The stories overall should challenge the positioning of able and healthy bodies as normalcy.

- When the sick characters are female, authors have a great opportunity to challenge more general standards of femininity rather than to support them. (The Patriarchy Is Killing Us, But Literally)

- Related to this, there’s plenty of opportunity for critique of the current medical establishment and its various problems, including refusing to take young women seriously when they report problems with their bodies.

- There’s also plenty of opportunity for political commentary of user-pays health systems, and how that alone can wreck families. Or how having an illness without a name is harder to deal with. Or how having an invisible illness is a different experience from having an obvious one.

- The stories should leave teen readers with a more nuanced and complex understanding of illness, including the surrounding politics.

- Artists, musicians and writers have got love covered, but few have managed to write what it feels like to be in pain. Especially chronic pain.

Anyone who has fought the medical establishment as a teenage girl knows that, as far as most doctors are concerned, teenage girls are not considered honest or accurate reporters of their own unusual symptoms

Deborah, Dreamwidth

FURTHER READING

The Portrayal of Protagonists with Communication Disorders in Contemporary Award-Winning Juvenile Fiction by Jane Lefevre. Authors need to be mindful of using discriminatory language and relying on stereotypical portrayals of characters with communication disorders. Auditory processing disorder remains unexplored in children’s literature.

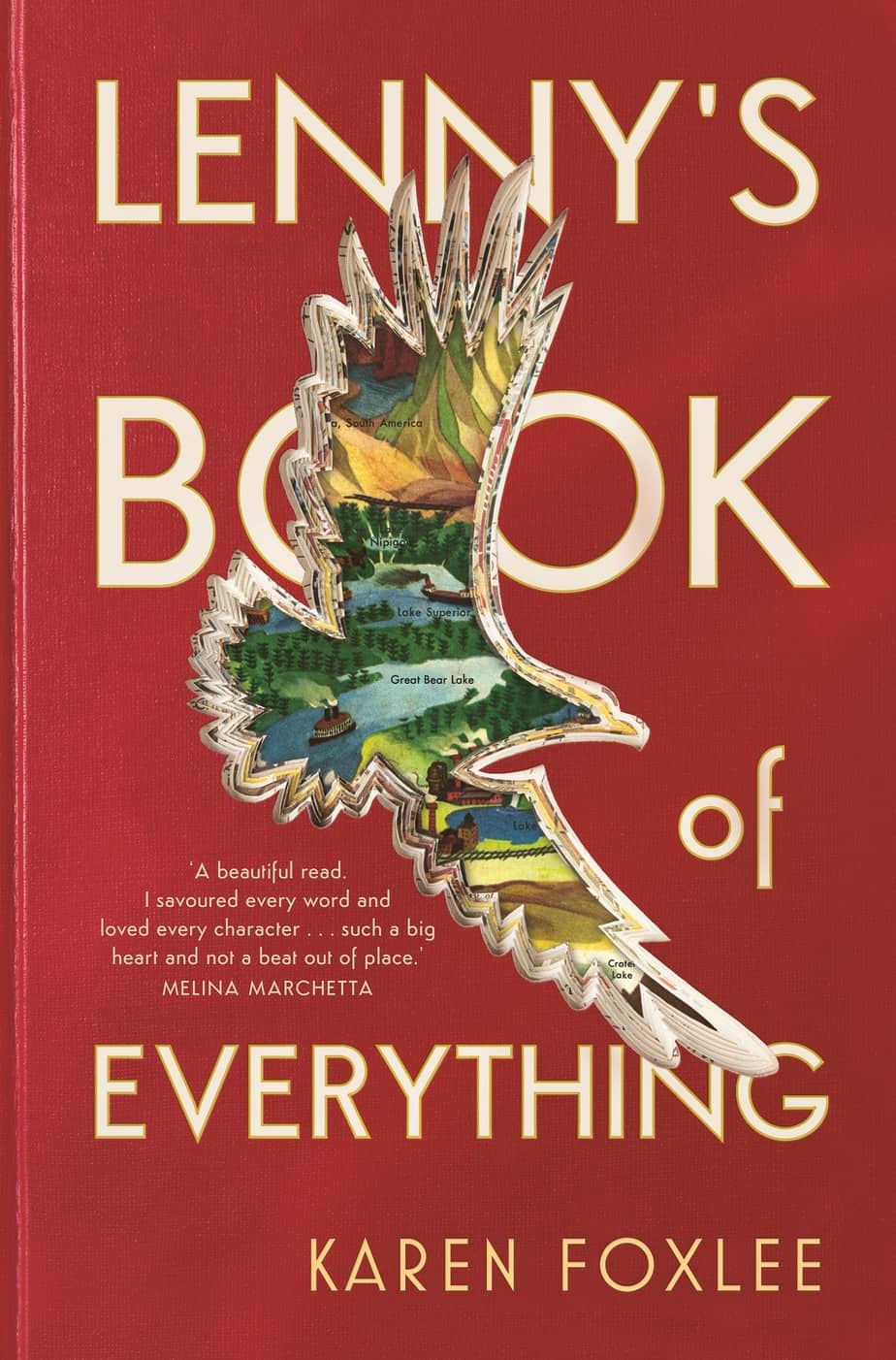

Lenny, small and sharp, has a younger brother Davey who won’t stop growing – and at seven is as tall as a man. Raised by their single mother, who works two jobs and is made almost entirely out of worries, they have food and a roof over their heads, but not much else.

The bright spot every week is the arrival of the latest issue of Burrell’s Build-It-at-Home Encyclopedia. Through the encyclopedia, Lenny and Davey experience the wonders of the world – beetles, birds, quasars, quartz – and dream about a life of freedom and adventure, visiting places like Saskatchewan and Yellowknife, and the gleaming lakes of the Northwest Territories. But as her brother’s health deteriorates, Lenny comes to accept the inevitable truth; Davey will never make it to Great Bear Lake.

An outstanding novel about heartbreak and healing by an award-winning author.

Reframing Disability in Manga

Reframing Disability in Manga (University of Hawaii Press, 2020) analyzes popular Japanese manga published from the 1990s to the present that portray the everyday lives of adults and children with disabilities in an ableist society. It focuses on five representative conditions currently classified as shōgai (disabilities) in Japan―deafness, blindness, paraplegia, autism, and gender identity disorder―and explores the complexities and sociocultural issues surrounding each. Author Yoshiko Okuyama begins by looking at preindustrial understandings of difference in Japanese myths and legends before moving on to an overview of contemporary representations of disability in popular culture, uncovering socio-historical attitudes toward the physically, neurologically, or intellectually marked Other. She critiques how characters with disabilities have been represented in mass media, which has reinforced ableism in society and negatively influenced our understanding of human diversity in the past.

Okuyama then presents fifteen case studies, each centered on a manga or manga series, that showcase how careful depictions of such characters as differently abled, rather than disabled or impaired, can influence cultural constructions of shōgai and promote social change. Informed by numerous interviews with manga authors and disability activists, Okuyama reveals positive messages of diversity embedded in manga and argues that greater awareness of disability in Japan in the last two decades is due in part to the popularity of these works, the accessibility of the medium, and the authentic stories they tell.

Scholars and students in disability studies will find this book an invaluable resource as well as those with interests in Japanese cultural and media studies in general and manga and queer narrative and anti-normative discourse in Japan in particular.

New Books Network