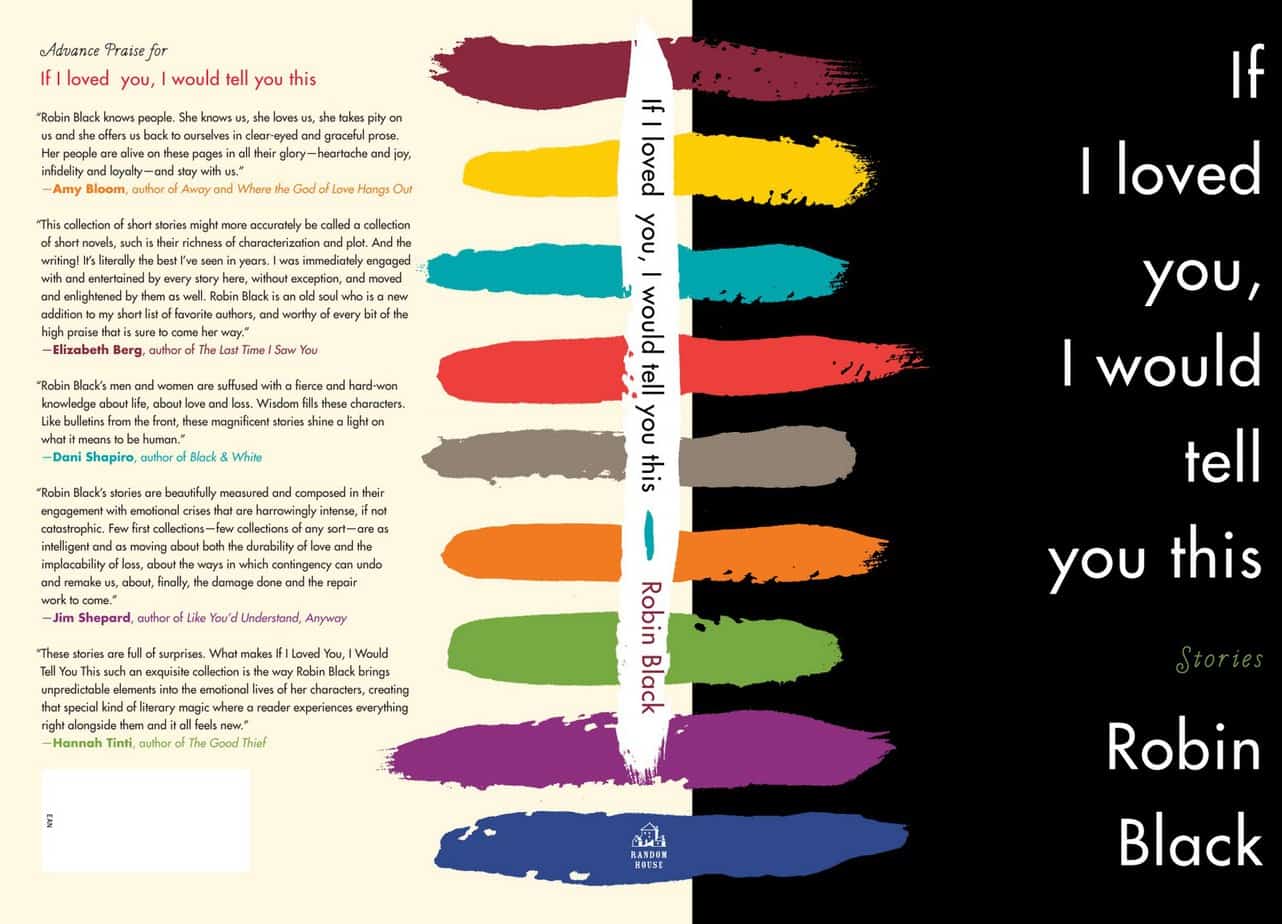

“If I Loved You” is a short story from a collection called If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This (2010), written by American author Robin Black.

A woman dying of cancer writes an imaginary letter to her new neighbour, who has uncharitably built a fence along their boundary line. This fence prevents her from getting conveniently out of her car in the driveway.

Here’s the subtext: this woman’s garage has obviously been built stupidly close to the boundary line, by someone who would never have predicted a future in which a new neighbour would want to build a fence. This is a comment on how we sometimes do things with great optimism. The optimism comes back to bite us later. Instead of optimism, this narrator now goes for ‘maybes’. (This explains the style of narration.)

That surface level plot about the fence offers a fairly didactic message about how we never know what’s going on in someone else’s life, symbolised by the fence itself. We put fences around ourselves to avoid considering other people’s pain.

But the story avoids didacticism because I happen to identify with the neighbour, somewhat. Significantly, this neighbour hasn’t done anything terribly bad. He has simply built a fence along his boundary line. Would you sacrifice a portion of the land you’ve just bought, and which you continue to pay rates on, because a neighbour either built a garage too close to the boundary line, or bought a house without checking the structures conform to council regulation?

MY OWN SIMILAR FENCE STORY

A few years ago our erstwhile neighbours owned three massive dogs — one of them scary and dangerous, and no doubt kept as a guard dog. In summer, with all the windows open, they barked whenever we chopped vegetables in our own kitchen. We needed a solid fence to replace the bamboo screen on wire, which sometimes failed to keep the dogs contained. We had a toddler. I couldn’t let her play outside.

But because the properties are 40m long, we couldn’t justify paying for the entire structure. The council provides forms to fill out when you want a neighbour to pay half of something. We got a quote for a fence, paid a surveyor in full, filled out a form and put it in the neighbours’ letterbox. I was too intimated by the dogs to enter the property and hand-deliver. (Even a police officer knocked on my door one day to ask if the dogs next door were safe.)

Later, the neighbour and I had a bit of a showdown in our kitchen because the neighbour was incensed at receiving such formal notification and insisted he couldn’t pay for any of the fence anyhow. He said we could pay the entire thing if we wanted it. Then he said he was about to move out further to the country anyway. Unsaid at this point: his marriage was breaking down. He had a variety of myalgia which meant he couldn’t work much. He could have written a story like this, had he been a writer, I guess.

Then, in an attempt to regain some power after admitting he could not help out with the fence, no way would he allow anyone to set foot on his property. He wouldn’t keep his dogs inside, either. So that put an end to the fence discussion.

How many of us have a story like that? It’s a highly relatable scenario. Robin Black goes into the psychology of that particular power dynamic, whereby one neighbour wants a fence, the other neighbour does not, so the neighbour in the low-power position wrests what little control they have to forbid anyone step onto their property to actually build it.

POWER AND RATIONALITY

This dynamic plays out in many different ways, even when there are no fences involved — one person loses power, tries to get it back, and takes unexpected action which sounds petty and completely irrational. But these decisions are completely rational when you look at the emotions behind the actions — regaining a sense of control. The same can be said of almost any ‘irrational’ action outside psychosis: Action is driven by emotion.

SUBJUNCTIVE NARRATION OF “IF I LOVED YOU”

The style of narration in “If I Loved You” is very interesting and I’ll do my best to describe it using words which probably aren’t the academic words.

First, the opening paragraph so you know what I’m talking about:

If I loved you, I would tell you this.

I would tell you that for all you know I have cancer. And that is why you should be kind to me. I would tell you that for all you know I have cancer that has spread into my liver and my bones and that now I understand there is no hope. If I loved you, I would say: you shouldn’t be so hard on me. On me and on Sam.

We don’t yet know who this character is talking to. We don’t know if she really has cancer, or if it has really spread. At this point, for all we know, she is a fantasist, or making a point about lack of empathy.

The best phrase I have to describe this style of narration is ‘subjunctive mood‘. If you’ve ever studied Spanish grammar you’ll know exactly what this means — it’s one of the more difficult aspects to master for English speakers because we don’t make much of a distinction in English, and where I come from, some uses are dying out. One day in the early 2000s, while teaching high school in New Zealand, I wrote a sentence on the whiteboard which included the phrase ‘if I were’. A fourteen-year-old put up her hand to tell me I’d gotten my grammar wrong. It should have been ‘if I was’, according to her, and the subjunctive use of ‘were’ (with its emphasis on the hypothetical, overriding the more frequent plural usage) sounded dead wrong to her. I found this language shift fascinating, but felt we were losing something in English if we completely lost modal verb distinctions between subjunctive and indicative mood. But are we really losing anything?

If the subjunctive mood can describe a sentence, perhaps it can describe an entire passage in a story. “If I Loved You” has a subjunctive title and continues from there.

Why this narrative style? I can think of several reasons.

- The story itself achieves some of its narrative drive by presenting information in a ‘is this true or not?’ kind of way, then keeping the ‘yep, it’s all true’ as reveals for the reader. This only works a few times, of course, after which the reader has been trained in the particular narrative style of the piece — though the narrator offers info that sounds like it may or may not be true, it is true. All of it ends up being true, assuming reliable narration. (And yeah, no narrator is 100% reliable.)

- But she’s having trouble saying all this. We learn a lot about the narrator’s psychology. She has a tendency to imagine how different things might have been. (I think this is common to most of us.) This is hardly a recipe for happiness, but it is also one way of coping with impending death. Maybe, some days, she can almost persuade herself that she’s not going to die of cancer at all. She is suspending herself in this permanent subjunctive mood. Some might call it ‘living in the moment’.

- It’s a more interesting way of presenting backstory. Basically, the first page explains to the reader that the narrator has cancer, the nature of the cancer, the backstory of the son. Normally writers are advised not to ‘infodump’ in the opening of a story because it supposedly bores the reader. But this story is an example of an exception to that rule and provides evidence of my preferred maxim — boring passages bore the reader. This is perhaps slightly boring information but its unusual presentation keeps our mind engaged. (“Is this person telling the truth, or not?”)

- The ‘what if’ feeling connects directly to one of the Anagnorisiss. (See below.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “IF I LOVED YOU”

“If I Loved You” is not a linear story — it’s a circular one which curls back onto itself offering deeper insights each time.

Part One is the story of the neighbour and the fence. There’s no epiphany in this one — just a mulling over of ideas.

Part Two is backstory about the cancer, and we are ready for more of that now, because we’re wondering who these people are. A character epiphany and a reader one.

Part Three is set two months after the fence went up and the narrator is closer to death.

Each part is a complete story in its own right, though I have fudged that a little below.

Jane Alison calls these plots Cumulative. For another story with a cumulative plot, though more exaggerated, see “The Fifth Story” by Clarice Lispector.

I’m also reminded of “Free Radicals” by Alice Munro. Both short stories are about women dying of cancer. Both contain a fantasy sequence and the reader is left to figure out how much of it is ‘real’ within the setting.

SHORTCOMING

The narrator is in a very weak position. She is dying of cancer. She has a son who causes her physical harm.

Her only real strength is the fact she’s in a long-term, good marriage.

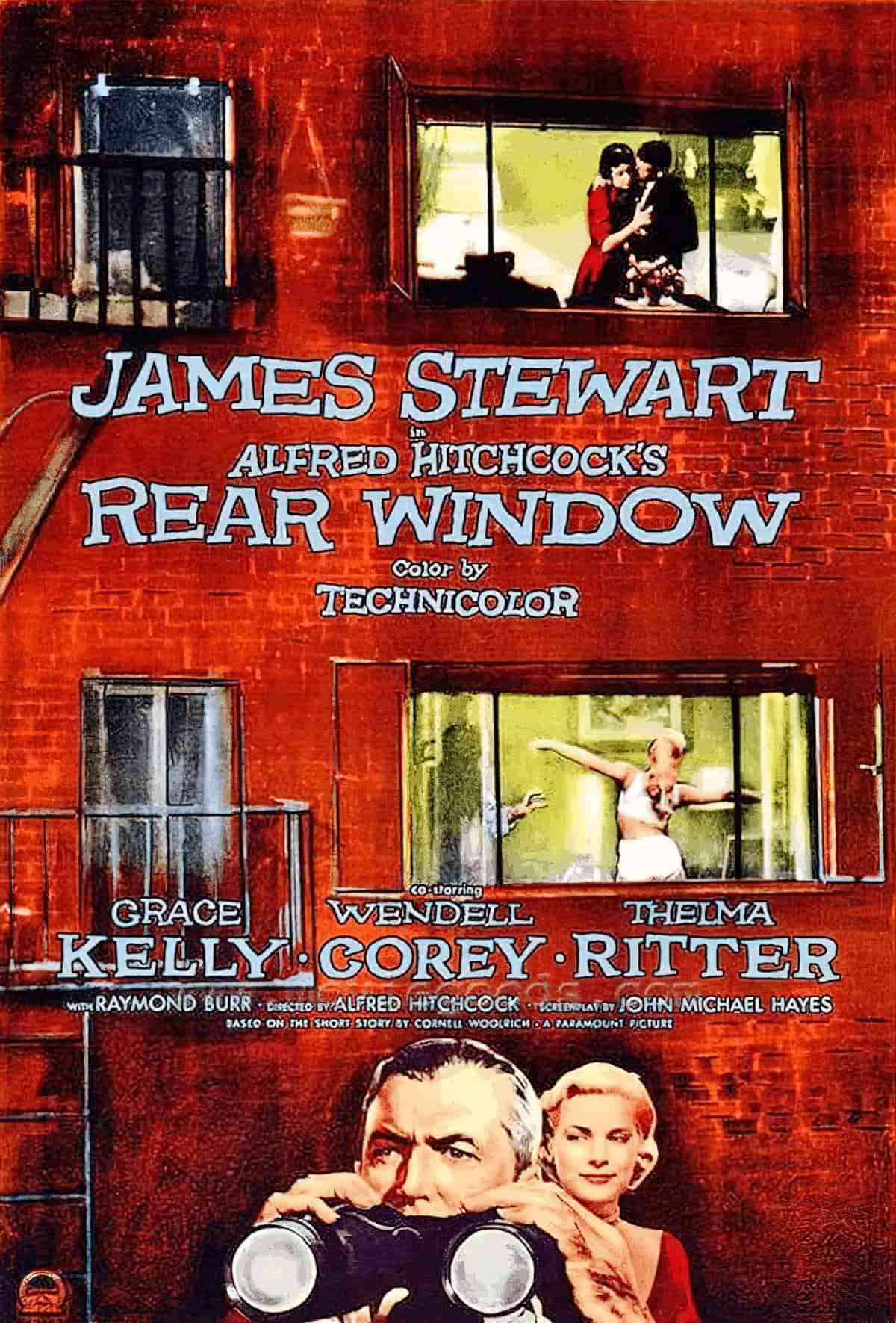

Something happens to her psychology as the story progresses and it’s not great. Though the word has been devalued from overuse, she’s starting to develop a bit of an ‘obsession’ with this neighbour. I’m thinking of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic film Rear Window in which a man with a broken leg notices things happening to his neighbours because he’s laid up with nothing else to do. (A scenario which probably no longer works in the age of smart phone ubiquity.) Interestingly, Rear Window is based on a short story.

I know that you go to work a little after [Sam] leaves—I hear the car door, the ignition. I know the hours you keep, can predict when you’ll come home…

DESIRE

To be able to get back into her own house after her medical appointments.

Also, it would be nice if people could empathise with others. Perhaps she would like to change the world for the better. The following paragraph says a lot about the wish to be seen.

I want to scold you in the harsh, caressing tones of a mother to a child. I want to help you, make you understand more about the way things should be than you do, make you think more, give you some imagination. I want you to imagine that I have a life. A life that matters. You should care about my life.

There’s a human tendency to look away from old age and death. This was perhaps worse in earlier eras, when life was harder in general and if you didn’t earn your keep you were literally causing your people extra work. Look at German fairytales (the ones seldom found in children’s collections) and you’ll find a lot of old women ‘behind the stove’. They were shoved away and forgotten.

In medieval times, if you wanted to get rid of your elderly person you might open the window for them as they lay in their bed, because that way the soul can easily escape. (More scientifically, they may also catch a cold which leads to pneumonia.)

OPPONENT

There’s a conversation that hasn’t been had, I tell Sam. The conversation human beings have with each other. He isn’t quite treating us like people.

He isn’t quite a person, Sam says. He’s a creature. He’s an animal himself. He’s like a yeti or something.

From this point on, Sam and the narrator privately refer to their neighbour as The Yeti. This is a counterstrike — he seems to have dehumanised them, so they’ll do the same back, by way of coping.

Cancer is also an opponent, of course. And the son who can’t control his violence. In this story, as in many others, you can plot opposition on a gradient from ‘natural and uncontrollable’ to ‘plotting, scheming, controllable’. (Only the latter kind of opposition is interesting to read about.)

PLAN

In her weakened position the narrator can do nothing. Her husband tries to reason, then they play out the petty fantasy of painting a wet red line and shooting the legs off builders who cross it.

Precisely because there is no plan of action, the act of writing this down is a plan in itself — first person storytellers are often achieving some sort of psychological resolution through the act of writing their frustrations down.

BIG STRUGGLE

Part Two, the cancer, the son, is the main Battle. In some ways, the neighbour and his fence is a proxy.

I heard someone say the other day that their health is failing terribly and now they have to deal with some annoying paperwork to do with electricity and overbilling. They don’t have the strength to deal with it. Someone else commented that exactly that sort of challenge can function as a good diversion when going through a difficult time. In short, people can respond in various ways to problem heaped upon problem.

ANAGNORISIS

The following sums up the author’s feelings towards anagnorises in fiction. She’s talking about an epiphany she had one day about her long-standing relationship with her husband:

I’m a fiction writer by trade, and these days the sort of epiphanies where characters suddenly understand what their problem has been all along are out of style. It seems so contrived, so unlikely. But the bar for plausibility is higher in fiction than in fact. Real life can be, often is, implausible — yet true.

— from Robin Black’s description of her AD/HD at the Chicago Tribune

In line with this view of story, which isn’t all that new, by the way — Katherine Mansfield wrote her last stories in this realistic style sans anagnorisis — Robin Black offers us ideas that Sam and the narrator turn over between them with no resolution.

This is a method used by YouTube philosopher Natalie Wynn. She explains all this in her XOXO talk, including her reasons for doing so. In making a point she sets up fictional characters who each argue a different side.

The same is done here, with two characters — a husband and a wife — talking through the nature of ‘bad people’, turning over the etiology of this guy’s decision — is he born bad or did something bad happen to him to make him this way? This (non) epiphany concludes part one of the short story.

In Part Two, though, we do have a genuine Anagnorisis. The narrator has always hoped that her disabled son knows who she is. But now she’s about to die, she hopes the opposite. She wishes her son be more like the uncaring neighbour because life seems easier that way.

The best character epiphanies are accompanied by a separate epiphany for the reader. We realise part of the reason for the subjunctive mood of this story. We realise why this mother thinks in ‘what ifs’:

My son is eighteen years old. His head is covered with thick black curls like my own used to be and his eyes are the same bright blue as Sam’s. He would have been a very handsome man. He would have been something wonderful. I’m convinced. But for the travels of a blood clot to his brain, while he burrowed small and silenced in my womb.

This paragraph is given the powerful position as last in Part Two. We are encouraged to pause on it.

By Part Three, the narrator’s relationship to time has changed.

The clock has lost its meaning. My relationship with time is more personal now.

Since time is rendered irrelevant, perhaps any distinction between reality versus fantasy can be rendered irrelevant, adding yet more weight to the subjunctive mood of this story.

What if? When? Who cares?

NEW SITUATION

“If I Loved You” ends with sideshadowing, although we could say this entire story is a sideshadow — an imaginary version of how things might be different.

I sometimes think that when I’m gone Sam will drive the car right into your well-constructed fence. I can picture it so easily: Sam behind the wheel pulling up into the drive, gunning it; and veering left. If the tables were turned, there’s no doubt it’s what I’d do.

That paragraph forms the Battle scene of Part Three (wholly imagined), and is swiftly followed by the final Anagnorisis:

Because who is there left to be angry at? Except you? We used up all the other obvious candidates long ago.