Wealth brings out the worst in people. This is the overriding message we get from stories in general, be they for children or adults. Rather, it is the dogged pursuit of wealth which makes people evil.

Noble people don’t do things for the money, they simply have money, and that’s what allows them to be noble.

Margaret Atwood

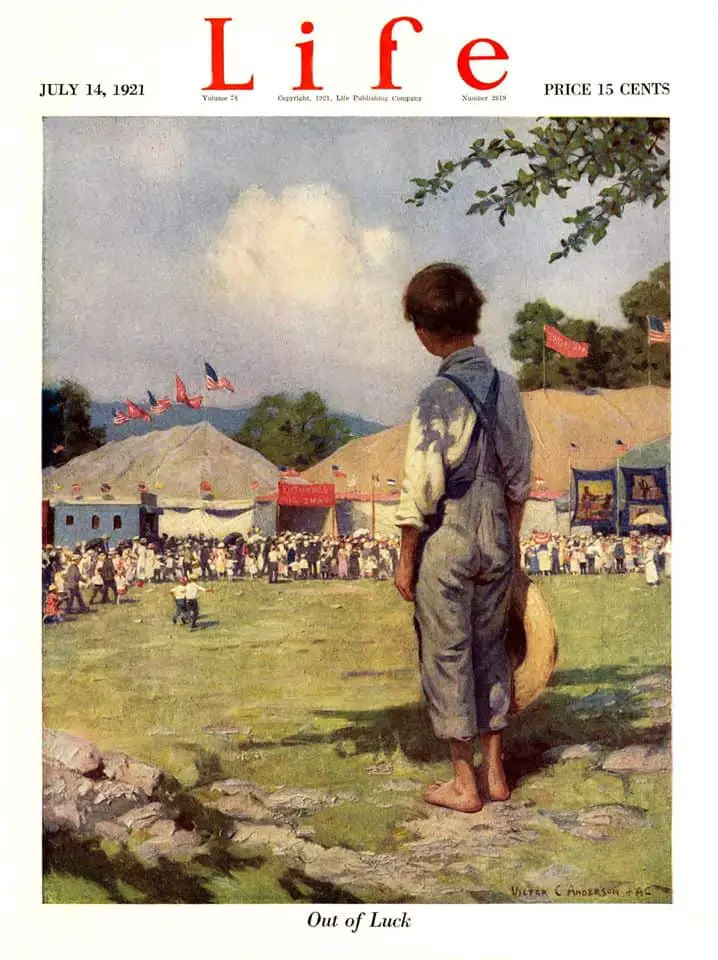

In popular storytelling, sometimes by working hard a hero can become rich. In a Cinderella story goodness leads naturally to riches. This is thought to be Cinderella’s rightful place — after all, Cinderella is not a rags to riches story. It’s a riches to rags to riches again story. The high born are thought to be worthy due to their superior bloodline.

In an attempt at subversion, characters in some stories are eventually revealed to be nice people despite being rich.

The Pursuit Of Wealth As A Story Goal

Of the three principal preoccupations of adult fiction — sex, money and death — the first is absent from classic children’s literature and the other two either absent or much muted. Love in these stories may be intense but it is romantic rather than sensual, at least overtly. […] Money is a motive in children’s literature, in the sense that many stories deal with a search for treasure of some sort. These quests, unlike real ones, are almost always successful, though occasionally what is found in the end is some form of family happiness, which is declared by the author and the characters to be a “real treasure.” Simple economic survival, however, is almost never the problem; what is sought, rather, is a magical (sometimes literally magical) surplus of wealth.

Alison Lurie, The Subversive Power Of Children’s Literature

A lot of children’s literature is set in a kind of utopia where the characters never have to worry about money. Food is always there. A classic example of that is The Wind In The Willows.

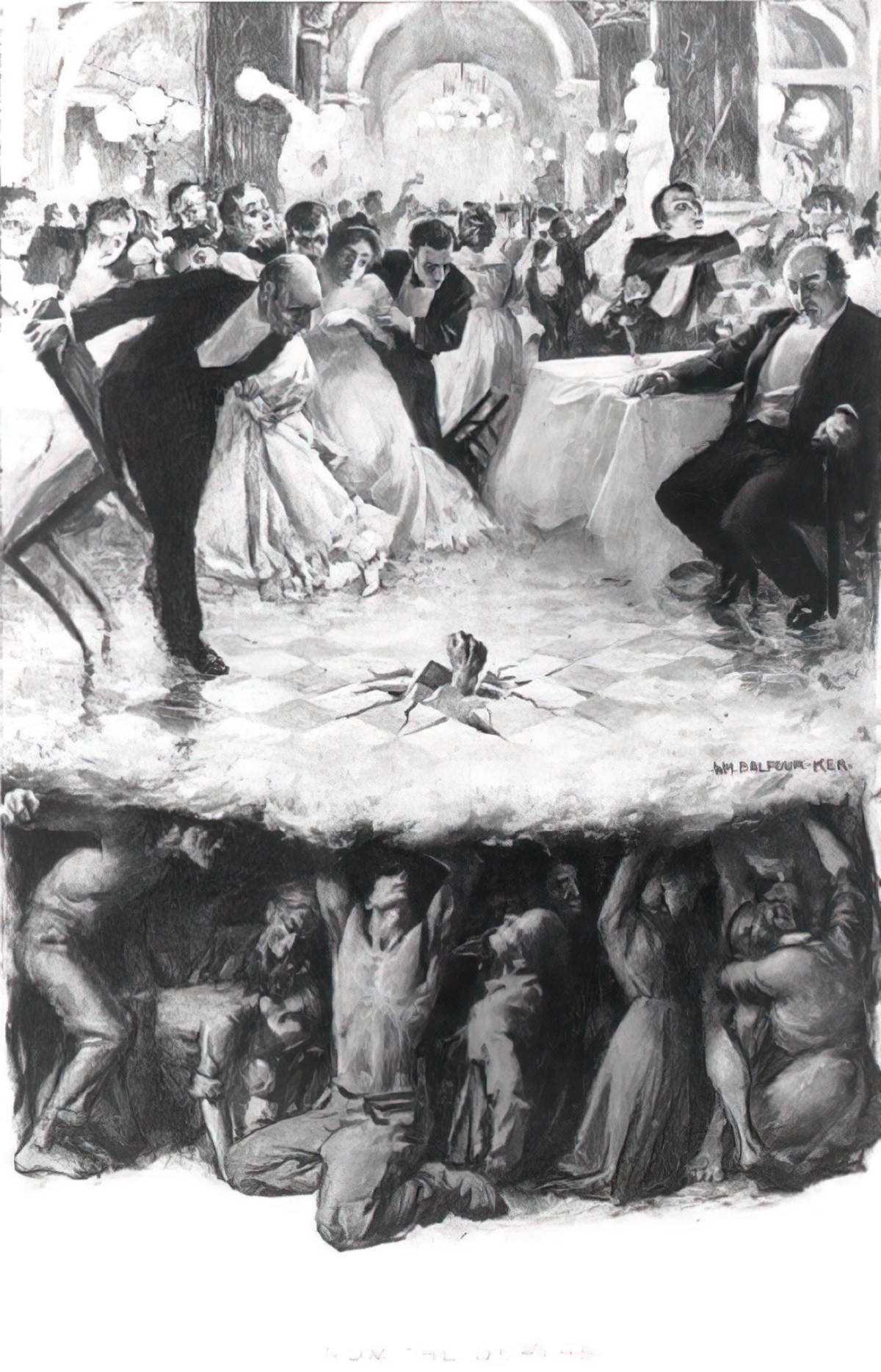

Storytelling Technique: Rich and Poor Together

One technique writers use to add interest and conflict to a story is to put wealthy and poor people in the same closed arena and force them to interact with each other. You’ll find this is done at some point in almost every TV show. Movies do it too.

However, there are a few political pitfalls to avoid when doing this.

Wealth Versus Poverty In Stories For Adults

- Annie Proulx makes use of the rich-poor divide a lot. She takes a rural community comprising simple, rural folk with anti-materialistic values and contrasts them with a rich blow-in. For more on that, see below.

- In Freaks and Geeks, episode four, Lindsay gets her first class culture shock when she visits Kim’s house for dinner. It turns out Kim has invited her only to prove to her parents that she’s responsible and deserves her confiscated car back. Lindsey is shocked by the chaos and by the state of Kim’s house.

- Katherine Mansfield herself was a daughter of the upper middle class but she tackled the rich-poor divide in several stories, most notably “The Doll’s House” and “The Garden Party“.

- Angie Thomas writes about race and class in The Hate U Give. Issues of wealth and privilege come to the fore because the main character is at a private school on academic scholarship.

- The Beverly Hillbillies — The farming Clampett family become suddenly rich when they discover oil in their backyard. This discovery turns a poor family to rich millionaires. They move to Beverly Hills, California. This is a good example of a fish-out-of-water story. These rustic characters clash with the people of one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in America. Rich-poor conflict is useful in Comedies of Manners.

- Pride and Prejudice is an early example of the Comedy of Manners. No one is poor, exactly — it’s all relative. The Bennett sisters are in danger of becoming poor in future. Their mother’s behaviour is crass in comparison to those of the mega-wealthy.

- Titanic — both the real story and the various fictionalisations which have emerged since, work well as stories because, when a boat is sinking, it doesn’t matter whether you’re rich or poor. Everyone goes down with it. This makes for an evergreen metaphor about looking after our planet.

- Stories with dragons (specifically Northern dragons) are metaphors for how hoarded wealth brings one no joy. Dragons have fiery or poisonous breath. They’re often curiously merry or sardonic because they consider themselves invincible. But they can be beaten or more often outwitted via some weak spot. (Eastern dragons are different beasts altogether — they are magical, influence the weather, are godlike and maternal.)

- Tomato Red — the love interest with the red hair feels a grave sense of injustice that they live in a mobile shack whereas other people in their town live in mansions. This fuels her desire to get out of that town, and justifies what she does in order to achieve it.

- Schitts Creek — The Rose family have already lost all their fortune by the time they hit Schitt’s Creek — a hole of a town the father bought the son for a birthday joke. They are now forced to live there among the regular folk. They may have no money but they have brought their rich tastes and attitudes with them. This makes for plenty of conflict.

- Animal Kingdom — J’s druggie mother dies of an overdose. At seventeen years of age he has only ever known poverty. But now he is taken in by his grandmother and uncles, who are running a criminal empire. These are the sorts of people who leave wads of cash lying around.

- Nashville — Juliette Barnes is now rich, having earned oodles of money as a country pop singer, but she has come from nothing. She grew up in a trailer park. The writers make sure the audience is taken back there, to explain some of Juliette’s back story. Juliette still has her mother in her life, which allows the audience to see rich and poor rubbing up against each other. Other characters undergo a rags to riches Cinderella story as part of the show.

- Upstairs Downstairs — Is the ultimate in rich and not rich rubbing up against each other. Downton Abbey is very similar. These shows are about class differences. For some of the characters real destitution is one wrong-doing away. Even the mighty can fall.

- Coronation Street — Even in a working class Northern town where everyone lives from month to month, we still have characters like Mike Baldwin who owns the factory, or Dev Alahan who owns the corner shop. Though these men are far from fabulously wealthy, there is still enough of a discrepancy in wealth to provide interest.

- I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore — our modest main characters make a visit to an ostentatious house with massive lawn ornaments under the guise of cops. When the lawn ornaments get broken this provides some catharsis for the audience because these rich people are not good and the main character is very sympathetic.

- Fargo — our main dude has a rich father-in-law, which causes all sorts of existential male angst, and therefore the impetus to make real money of his own. (Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.)

- Lonesome Dove — Clara’s husband has been a successful horse wrangler. Not only this, he married the love of Gus’s life. Larry McMurtry takes us to Clara’s ranch to make sure we get a taste of The Path Not Taken. Could Gus have had all this, if only he weren’t such a wanderer, basically married to Call?

- Gilmore Girls — This community offers us the full spectrum of wealth (well, right down to middle-class, anyhow). We have Emily and Richard at the top, with all their cronies. Next we have successful small business owners such as the owner of Doose’s market, and eventually Lorelai and Sooki themselves. Then there are the people who work for others.

- My Summer Of Love — Tamsin is the privately educated daughter home for the holidays in her family mansion while Mona is the working class girl from the pub. A little Yorkshire village is the perfect opportunity for these girls to meet — more so than London, probably — because country villages comprise tiny rows of cottages where the poorest people live, with ticky-tacky but newer cottages where middle-class people live (e.g. Mr Fakenham’s lover), but just beyond the town’s border lie the large homes of England’s aristocracy. Rich girl and poor girl legitimately share the same country road, though one rides a white horse and the other scoots along on a motorbike with no motor.

- American Honey — Star joins a ‘mag crew’ — a bus load of young people who have been recruited to sell magazine subscriptions across mid-west America. The bus takes them to wealthy suburbs and then to poor suburbs, juxtaposing them. The matriarch of the group is herself from a poor suburb but through psychopathic means has garnered enough money for herself to wear some of the trappings of wealth. She offers commentary on the people who live in these places as she drops her crew off.

Wealth Versus Poverty In Stories For Children

It’s interesting to see how wealth discrepancy is handled in stories for children. In picture books there is very rarely any social commentary on money. Olivia (by Ian Falconer) lives in a big New York City apartment and must therefore have mega wealthy pig parents, but because she goes through similar dramas as many (white) kids, the reader is not encouraged to mull that one over.

The work of Frances Hodgson Burnett — The phrase ‘rags to riches’ is commonly used to describe an arc in which the main character lives in poverty at the beginning of the story and in wealth by the end. But more commonly in the Victorian era the plot is one in which a disadvantaged person, often a child, is restored to the wealth and positin which are thought to be his/her natural birthright. Even Cinderella isn’t a genuine rags to riches tale — Cinderella must have been at least middle class to begin with or she would not have had those middle class relatives.

Ivy + Bean — Ivy seems to come from a richer family. She has a big bedroom with a craft table set up. Money is not mentioned. It may just be that Ivy’s mother is super organised and particular, and likes to dress her little girl in fancy frocks. But an adult reader assumes some discrepancy in income between the households. Ivy is originally depicted as a prissy, unsympathetic character, but after the first book the two girls realise they have a lot in common and become firm best friends. Not only that, Ivy is revealed to be every bit as devious as Bean. The message: Some kids are rich, others not so much, but they’re all just kids in the end.

Wimpy Kid, Dog Days — Holly Elizabeth Hills is one of Greg’s classmates and also an unrequited love interest. Greg tries to impress her but can’t. Her family is shown to be wealthy, playing on the old folk tales in which lovers are kept apart due to differences in class and status. The sister is portrayed as tyrannical, spoiled and selfish. The message: While being rich doesn’t necessarily make a girl undesirable, the existence of the sister conveys the idea that the riches themselves have contributed to her personality.

“I have dreams about those shoes. Black high-tops. Two white stripes.”

All Jeremy wants is a pair of those shoes, the ones everyone at school seems to be wearing. But Jeremy’s grandma tells him they don’t have room for “want,” just “need,” and what Jeremy needs are new boots for winter. When Jeremy’s shoes fall apart at school, and the guidance counselor gives him a hand-me-down pair, the boy is more determined than ever to have those shoes, even a thrift-shop pair that are much too small. But sore feet aren’t much fun, and Jeremy comes to realize that the things he has — warm boots, a loving grandma, and the chance to help a friend — are worth more than the things he wants.

Harry Potter — It’s impossible to consider the ideology of wealth in the Harry Potter series without thinking of the rags to riches tale undergone by the author herself. In the Harry Potter universe the Black family is one of the mega wealthy. But Sirius Black was not born wealthy — he inherited 12 Grimmauld Place and this made him rich. He is fairly generous with his wealth. Gilderoy Lockhart is worth quite a bit. Harry Potter himself is also rich, especially for a twelve year old. He has inherited. It is extrapolated that after the series ends Harry goes on to become very rich. The Malfoy family and Bellatrix Lestrange are also wealthy. A lot of these rich characters are intermarried and related, keeping wealth in the family, in aristocratic tradition. The message: You don’t have to be all that great of a person to be born rich, but if you’re good like Harry you may well become rich through hard work, humility and dedication to a cause.

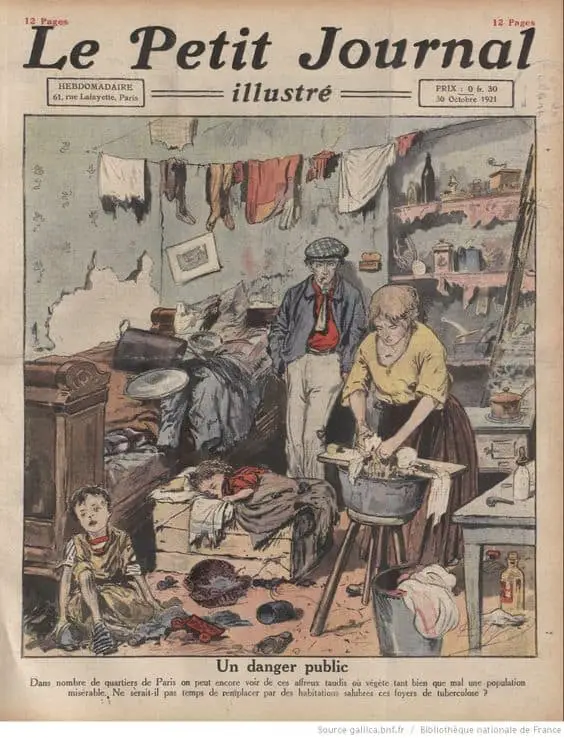

The Hundred Dresses — This book is about a modest, middle-class town whose children are strangers to poverty. Until one day, that is. These days it’s hard to tell the poorest children (in real life) by looking at them — clothing has come down in price and decent chainstore clothing is available cheaply from second hand stores. But in earlier eras clothing was prohibitively expensive and it was easy to tell the poor children at a glance. The message: Don’t judge people on their appearance. There is always more going on than you realise. Show compassion for those less fortunate.

Strays Like Us — Molly Moberly has been poor all her life and is even now living in poverty with a great aunt, but it turns out she has a rich grandmother who will now be her benefactor, of sorts. The grandmother is a lonely hypochondriac who won’t leave her bed. The message: If you have a destitute personality, money can’t buy happiness. You’re better off being modestly poor but mentally well.

Best friends Sofia and Maddi live in the same neighborhood, go to the same school, and play in the same park, but while Sofia’s fridge at home is full of nutritious food, the fridge at Maddi’s house is empty.

POLITICAL ISSUES

- Disenfranchised people with little power make easy targets.

- The main character of classic children’s book Heidi is rewarded by material wealth for moral virtue, with the following implicit message: If you are good, wealth will come your way. Ergo, if you’re not wealthy, you obviously are not good enough.

THE MYTH OF MERITOCRACY

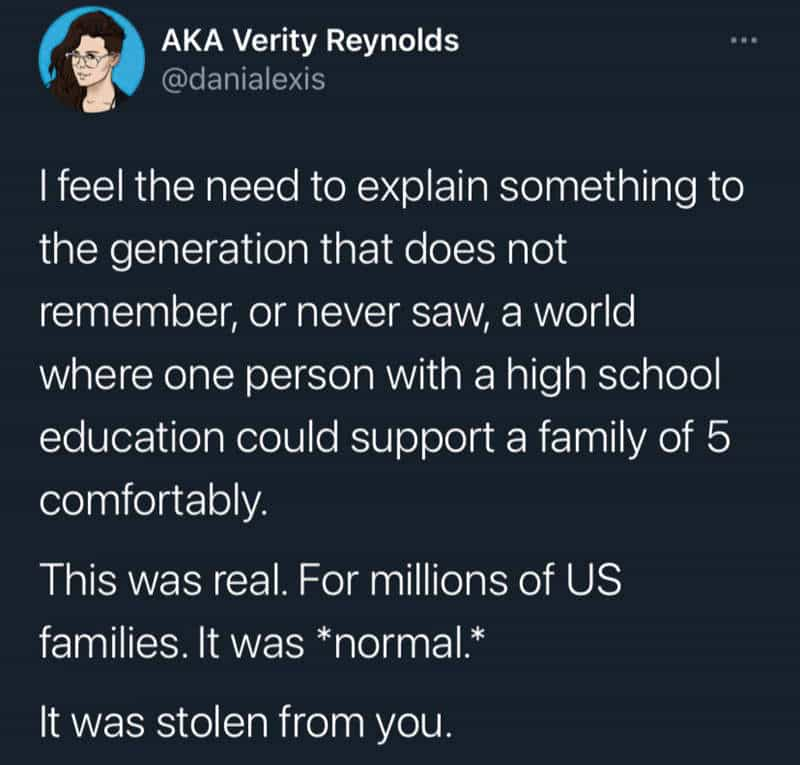

Institutional classism cannot be confronted without dealing with its accompanying myth of meritocracy, which suggests that if a person has a lower social class than they would like, they can “pull themselves up by their bootstraps,” because “anybody can get ahead if they try.” This mentality leads to faulty assumptions that people who have a lot earned it and people who don’t have a lot haven’t tried enough. Debunking this myth presents a challenging dialogue in that it intersects with class privilege, and os those who do have wealth may get defensive that they deserve what they have and have “earned it”.

Reframing Difference in Organisational Communication Studies by Dennis K. Mumby

My schooling gave me no training in seeing myself as an oppressor, as an unfairly advantaged person, or as a participant in a damaged culture. I was taught to see myself as an individual whose moral state depended on her individual moral will.

Peggy McIntosh

Q&A With Lani Guinier: Redefining The ‘Merit’ In Meritocracy at NPR

THE MYTH OF GENTILITY

A Bluebeard retelling like Rebecca feels outdated now because the entire revelation rests on the ‘surprise’ that a genteel, upper-class member of the aristocracy could possibly be a murderer. The ship has sailed if you were hoping to tell that kind of story.

WRITE PRIVILEGE AS AN INVISIBLE KNAPSACK

Privilege is typically invisible for those who have it. This phenomenon has been pointed out by many since, but in 1993 Peggy McIntosh came up with the phrase ‘invisible knapsack’ to describe privilege: an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was “meant” to remain oblivious.

MUST WRITERS ALWAYS ‘PUNCH UP’?

Writers—especially comedy writers—are often told: when mining character for comedy, always punch up.

This bit of advice means, in effect, that the underdog must win. The underdog has the last laugh. Ideally, the poor underdog is also likeable. That papers over a lot.

But in real life, the underdog often loses. What if you don’t want to create comedy? What if you want to create a realist setting in which rich folk often win, precisely because of their resources? What if you need to say something a bit more… true?

Annie Proulx’s short stories make for an excellent case study in how to create a rounded cast of downtrodden characters who neither win nor lose, but who plod along in their lane, no more or less enlightened than the rich bastards who blow in to their natural worlds. Proulx’s fatalistic world view definitely helps her convey the idea that we are all products of our environment, and that wealth or lack thereof is part of what shapes us. Her rugged, harsh landscapes also lead the reader toward an egalitarian view of humankind, in which everyone is the size of the ant in comparison to the mountains and plains, and everyone is therefore equal.

The Beverly Hillbillies gets a pass precisely because the rich milieu is satirised: The culture and society of Beverly Hills is depicted as obsessive and superficial. The locals have an unhealthy obsession with money, social-climbing, and the latest fashions. The Beverly Hillbillies are, in contrast, straight talking honest folks, who never wear a mask. They know exactly who they are, and are therefore happy in themselves, free from pecking-order pressures.

I’ve never given poor people credit for having noble souls, on the pretext that they are poor and only too well acquainted with life’s injustices. But I have always assumed that they would be united in their hatred of the propertied classes. Gegene has set the record straight on that score and taught me this: if there is one thing that poor people despise, it is other poor people.

The Elegance Of The Hedgehog, Muriel Barbery

The psychological effect of poverty is what lasts. You can send in rice to heal them and for energy but beware of giving energy to desperate people. They’re going to use it…. The hunger is bad but then you’d need about nine million therapists, who’d never be equipped anyway.

Frank McCourt on Writing About Poverty

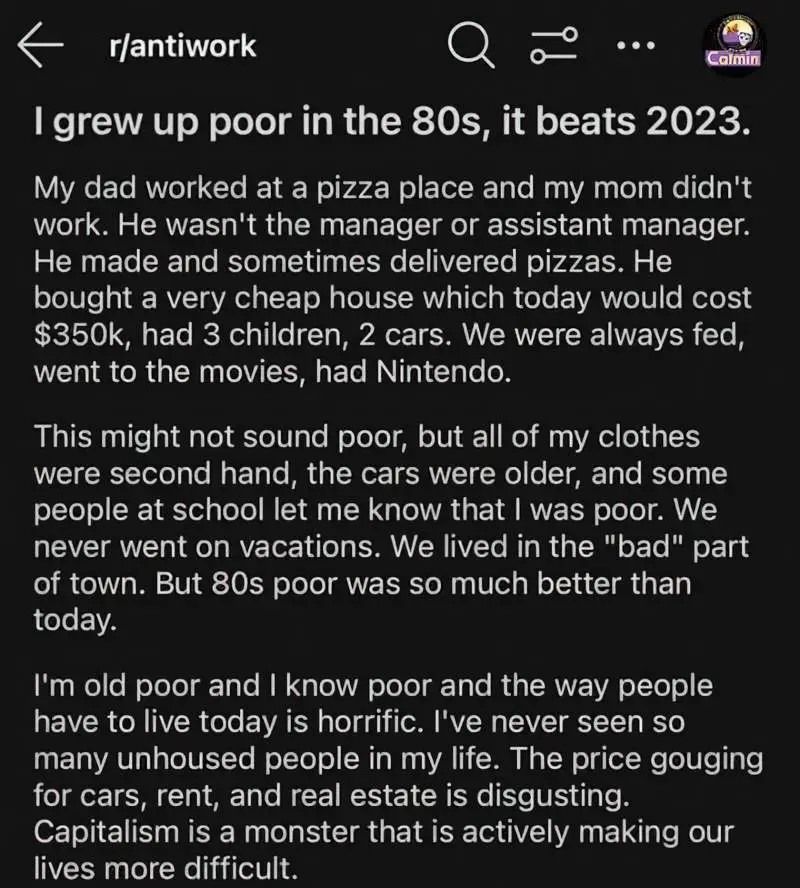

CAPITALISM

- Capitalism – anybody can be rich.

- Communism – nobody can be rich.

- Socialism – anybody can be rich but nobody should be poor.

ALSO INTERESTING

- On Being Broke vs. Being Poor from Jezebel

- Will reading make you rich? from Salon

- The Psychology of Wealth from TSP

- How do you get someone to lose interest in their hobby? Pay them to do it from io9

- 10 Things More Likely To Happen Than Winning The Mega Millions from Untitled Magazine

- The mathematical law that shows why wealth flows to the 1% from The Guardian

- The Queen Of Versailles, a movie length documentary, is perhaps the most depressing thing I have seen this year.

- And this movie-length documentary is the best display of genuine assholery ever.

- College Is Only Good for Helping Rich People Get Richer from GOOD

- Desperately Seeking Sugar Daddies. A young woman looks for a rich man to pay her for being a girlfriend. Yes, that’s a thing and I don’t know why I’m surprised, from Thought Catalog

- Is Money More Important For Men? from Good Men Project

- Researcher finds wealth shapes an ideology of self-interest and entitlement from Psy Post

- The Inequality Map from NY Times

- The Future Of Inequality from Overcoming Bias

- Is Equality Feasible? an article by Lane Kenworthy (Answer is yes.)

- How Class Works (in America) — an interactive guide from NYT

- Crowdsourcing Equality from Foz Meadows

- My Basic Proposition Is Equality, from Anne Summers. Yes this, this exactly.

- Wealth Inequality In America — perceptions versus reality, on YouTube.

- Free Markets and the Myth of Earned Inequalities from 3a.m.

- What ‘Girls’ and ‘Shameless’ Teach Us About Being Broke and Poor from The Nation

- In Rust Belt, a teenager’s climb from poverty, from The Washington Post

- You Can’t Afford To Lose Your Temper When You’re Poor, as well as a few other things, from Blue Milk

- Rachel Hills points out that ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ is a false dichotomy.

- Is there such a thing as ‘the privileged poor’? from Rachel Hills at Daily Life

- Why Do The Poor Become Parents? from The Dish

- Why It’s Not Altruistic To Help The Poor from Sociological Images

- How Poverty Taxes The Brain from The Atlantic

- Bad Decisions Don’t Make You Poor. Being Poor Makes for Bad Decisions, from Slate

- What’s Killing Poor White Women? from The American Prospect

- Assume Your Audience Contains Poor People from Sociolab

- 7 Things No one Tells You About Being Homeless

- Class Navigation: On being poor from The Toast

- Minimum Wage Was Once Enough To Keep A Family Of 3 Out Of Poverty from The Atlantic

- What Does Living In Poverty Really Mean? a podcast from NPR

- For 50 years, films have largely failed to fight the war on poverty, from Film School Rejects

Header painting: Arthur Dixon – The King’s Daughter

The bestselling, comprehensive, and carefully researched guide to the ins-and-outs of the American class system with a detailed look at the defining factors of each group, from customs to fashion to housing. Based on careful research and told with grace and wit, Paul Fessell shows how everything people within American society do, say, and own reflects their social status. Detailing the lifestyles of each class, from the way they dress and where they live to their education and hobbies, Class is sure to entertain, enlighten, and occasionally enrage readers as they identify their own place in society and see how the other half lives.

[The] debate about who gets to tell ‘authentic’ working-class stories – or even who watches them – is emblematic of a common trajectory of broader arguments about social class, which we argue frequently slip into the much narrower framework of ‘cultural authenticity.’ Commonly, such debates centre around the question of what (or who) counts as working-class, a heightened issue in Britain where unusually large numbers of people self-identify as such – illustrated most recently by research highlighting the discursive strategies adopted by middle-class Britons to position themselves as working-class.

Who Can Tell A Working-Class Story? Examining the representational limits of class in I, Daniel Blake (2016) and beyond by Jacqueline Gibbs and Aura Lehtonen

16th April 2021