What are psychotropic drugs?

Psychotropic drugs include:

- Antipsychotics (used in the treatment of schizophrenia and mania)

- Anti-depressants (tricyclics, SSRIs, MAOIs etc.)

- Anti-obsessive Agents

- Anti-anxiety Agents

- Anti-panic Agents

- Stimulants (used in the treatment of AD/HD)

Mental health remains highly stigmatized. While adults who need blood thinners, cholesterol-lowering medication and insulin can take their drugs without fear of judgement, making the decision to drug your child with psychotropic drugs is considered controversial.

What does this all have to do with children’s literature? Surely writers are steering clear of the topic. When was the last time you read a best-seller that said anything at all about your child’s AD/HD medication, for instance.

The Incorrect, Dominant Ideology Of AD/HD Drugs In Children’s Literature

Goes something like this:

When children are given AD/HD drugs they lose their creativity along with the very thing that makes them kids. ADHD drugs, if anything, *enhance* creativity by allowing the child some much-wanted brakes on the frontal cortex. The mistaken idea that ADHD drugs take away the wonderful things about ADHD kids mean that, especially in this country (Australia), ADHD drugs are less likely to end up where they’re needed.

There’s also this idea that AD/HD is what can happen to any of us if we’re not careful to exercise our brains, for example by reading long books. Here’s an example of that assumption, this time from an interview (with Ray Bradbury) in The Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think you prefer short stories to novels? Is it an issue of patience? They call it attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder these days.

In fact AD/HD is a matter of different brain wiring. No one is correctly calling ‘short attention span’ attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. This idea goes completely unchallenged in The Paris Review literary magazine.

When it comes to children’s literature, there is also a fetishization of The Natural. This is seen in ‘country kids are more wholesome than city kids’, and extends (of course) to what adults are putting into their children’s bodies:

The wholesome fictional child eats natural, home-cooked, home-grown food, with eggs collected by hand-raised hens. The wholesome fictional child is naturally exuberant and energetic and should never be given chemicals in a capsule to dampen their wonderfully childlike spirit.

Related to that:

Children are naturally energetic. Many AD/HD children move a lot. Therefore, AD/HD children are the epitome of childlike and should be allowed to continue as they are.

An unchallenged assumption:

AD/HD children are always happy to be AD/HD and would not change a single thing about themselves, including the option to put some chemically induced brakes on their oftentimes embarrassing and humiliating impulsivity.

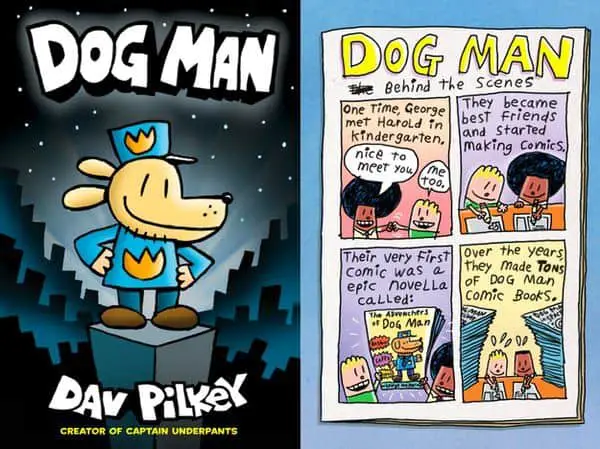

Commentary On Psychotropic Drugs In Dog Man by Dav Pilkey (2016)

Dog Man is a comic by Dav Pilkey (of Captain Underpants fame) who is now writing and illustrating a comic series ostensibly created by his young heroes of Captain Underpants.

Even fun books like this can’t avoid serious ideas at their core. Jokers have to make fun of something, in other words. Who’s going to be the butt? Mostly it’s actual butts, and a whole bunch of dog related jokes, which are safe.

On one page there is a note home from Ms Construde, to Mr and Mrs Beard informing George’s parents of his disruptive behaviour in class. Inspired by Dav Pilkey’s own experience of school, these boy characters are constantly in trouble for drawing comics in class when they should be working on assigned projects. Near the end of this letter it says:

We … believe that you should consider psychological counselling for your son, or at the very least some kind of behaviour modification drug to cure his ‘creative streak’.

By making this joke the teacher obviously oversteps her boundaries. Teachers should not be asking parents to put their children on drugs. This encourages us to dislike Ms Construde. This is evidence of how much this teacher dislikes creative children. She prefers conformist kids.

More problematically: the reader is at no point encouraged to criticise the teacher’s understanding of the drugs themselves. This spreads a widely misunderstood idea about what stimulant medication does for a child with genuine AD/HD. (A separate issue entirely: in some parts of the world children are being misdiagnosed and wrongly medicated.)

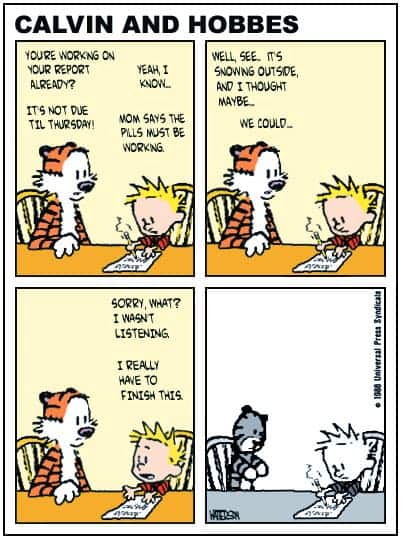

The AD/HD Calvin And Hobbes Meme

There’s a Calvin and Hobbes cartoon which shows the same ideology. Watterson himself did not draw it, but the ‘fake ending’ is widely known across the Internet and is as influential as any of Watterson’s own strips.

Because this cartoon punctuates the end of an era, it really does feel like the saddest thing ever. The ideology is clear: When Calvin is given drugs (a clear reference to AD/HD medication):

- He loses his imagination.

- The world seems less colourful.

- Calvin, as well as his toy, is now less of a human being and more robotic.

This is simply not how AD/HD drugs work. AD/HD medications stimulate an underactive part of the brain. They take nothing away from the person taking them.

Let’s say Calvin is AD/HD. He’s been through an extensive battery of tests conducted by numerous professionals, he’s had a psychologist come to his classroom to observe his behaviour, and he has his medication adjusted every six months by an experienced pediatrician to check he’s still on the best dose for him. This is the reality of AD/HD medication, at least in Austrlia.

Here’s the first thing that would happen: He would indeed be less interesting as a fictional character, mostly because he’d avoid trouble with authority figures. Less conflict means less drama.

If Calvin were a real boy, however, he would also:

- Be more likely to continue his schooling, and his level of education would more closely match his innate abilities

- Be less likely to take street drugs in his teen years

- Be less likely to attempt suicide

- Be less likelihood of depression

- Have more real world friends

- Have higher self-esteem

He may replace his imaginary tiger with a real world friend, but his power of imagination would remain intact. Instead of quitting his most imaginative projects before he’s seen them through, he would be more likely to produce something of value in the world, gaining intrinsic rewards from doing something the neurotypical population takes for granted — finishing something hard and frustrating.

AD/HD Characters Here, There And Everywhere

Children’s literature is chock full of potential AD/HD heroes and heroines. Very few of them are drugged, and rightly so.

I believe Anne Shirley can be read as AD/HD, for example. Anne Shirley is older than the medications themselves.

In modern stories, with Anne Shirley as the grandmother, AD/HD type behaviours are seen more frequently in children’s book protagonists than in the real population. AD/HD is great for storytelling:

- AD/HD kids are proactive. They’re never passive. They will be the kid to get the party started (or the house fire). They aren’t sitting around waiting to be Called To Adventure.

- AD/HD kids are in constant conflict, not only with authority figures but also with peers and siblings. You know the only thing that benefits hugely from plenty of conflict? Popular fiction.

- AD/HD kids are often very smart, articulate and quirky. This makes for great dialogue and also means that however much of a problem they are for ‘bad’ teachers, they tend to be beloved by ‘good’ teachers, who can see beyond their impulsivity and hyperactivity to the smart kid they are. There’s nothing like an AD/HD student to sort out the Trunchbulls from the Miss Honeys. AD/HD kids therefore allow a writer to write in a more black and white fashion.

- AD/HD kids cycle quickly between highs and lows, making for quick and interesting changes in emotional tone.

Without wanting to spread the idea that normal childlike behaviour must be AD/HD, good candidates for different brain wiring include a lot of the girls from chapter books and middle grade series, including:

- Junie B. Jones

- Ramona Quimby

- Pippi Longstocking

- Judy Moody

The same behaviours in boys are often read as ‘typically boyish’ and we’re also in the age of the ‘white every boy’ insofar as middle grade boy heroes go. However, my AD/HD daughter is a huge fan of Diary of a Wimpy Kid* and she says Fregley and Rowley may be AD/HD. (I say ASD for Fregley — it’s impossible to draw a line sometimes, and very common to be both.)

*Without her life-changing AD/HD medications, my daughter may not sat still long enough to read a single book let alone an entire series. There’s a very good reason why these fictional children are not given drugs. Indeed, drugs are not even mentioned. They make for more interesting fictional characters when their young lives are in turmoil.

The Modern Challenge For Authors And Publishers Of Children’s Literature

- AD/HD children who themselves take medications need to see themselves reflected in the stories they read. It seems as though no one else out there in children’s book world takes drugs. The diversity movement needs to include on-the-page neurodiversity and on-the-page drug taking.

- Young AD/HD readers are also entitled to an accurate depiction of their very real-world drugs. We are not seeing that.

FURTHER READING

Last season on Riverdale, it was revealed that Betty, the whip-smart, do-gooder in the group, had been taking Adderall to help her with her school work. This isn’t the first time that this stereotype has been used in a TV show targeting teenagers; even Spencer from Pretty Little Liars had a storyline involving her amphetamine addiction. But while Adderall is often depicted as a secret weapon that smart kids use when they’re under a lot of pressure, there’s a lot more to it than that, which people using it IRL may not know.

4 Questions You Probably Have About Adderall

Carl Hart speaks with Kim about America’s punitive drug laws, and how we might change them for the better. He argues that we should legalize and regulate the sale of all drugs, in the same way we regulate the sale of alcohol, to improve the health, equity, and liberty of our society.

High Theory Podcast