“I Stand Here Ironing” is a 1950s short story by American feminist and activist author Tillie Olsen (1912 – 2007). This is one of those stories which will likely hit differently if you’re a parent, especially a mother. That said, everyone has been parented by somebody, so every reader has the capacity to ‘get’ what this story is doing.

WHO WAS TILLIE OLSEN?

Tillie Olsen was born to Russian-Jewish working class parents in the American Midwest and dropped out of school at the age of 15 to enter the workforce.

I just read an Alice Munro short story about a girl who did the same thing (“How I Met My Husband”). To put the age of Tillie Olsen into context for you, Olsen gave birth to her first daughter (the eldest of four) in 1932, and Alice Munro was born in 1931. So Tillie Olsen is the ‘mother generation’ of Alice Munro, assuming you’re a fan of Alice Munro.

On that topic, Alice Munro wrote a number of feminist short stories about women who wanted to write but who had neither the time, the mental space nor the encouragement. “The Office” is very directly about that, but Munro’s entire Lives of Girls and Women is also about that. Tillie Olsen was very clear-eyed about how men’s writing is treated very differently from women’s writing. She explicates this at the beginning of her book Silences, which she started writing in 1962.

SILENCES BY TILLIE OLSEN

First published in 1978, Silences single-handedly revolutionized the literary canon. In this classic work, now back in print, Olsen broke open the study of literature and discovered a lost continent—the writing of women and working-class people. From the excavated testimony of authors’ letters and diaries we learn the many ways the creative spirit, especially in those disadvantaged by gender, class and race, can be silenced. Olsen recounts the torments of Melville, the crushing weight of criticism on Thomas Hardy, the shame that brought Willa Cather to a dead halt, and struggles of Virginia Woolf, Olsen’s heroine and greatest exemplar of a writer who confronted the forces that would silence her.

Fans of Margaret Atwood should investigate Tillie Olsen’s work. Despite not having a huge body of work to her name (due to the busyness of womanhood explicated by this very story), Margaret Atwood has named Tillie Olsen as a major influence.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “I STAND HERE IRONING”

- Who is the ‘you’ addressed in the narration? Who is narrating this story, and why do you think they are not named?

- Did you find yourself identifying more with Emily, or more with the mother?

- Why does Emily’s mother seem to regret how she has brought up her daughter? Do you think that regret is the appropriate emotion here? How accountable can parents be for how their children turn out?

- Approximately how old was this mother when she gave birth to Emily? (How old is Emily now, and how old does that make Emily’s mother now?)

- How was Emily raised differently from her siblings, and why?

- Why does the mother refuse the invitation to speak with the outsider about Emily? What experience has she previously had with so-called ‘experts’?

- What meaning does the mother ultimately find in her reflections about raising Emily and how she has turned out so far? (Talk about the “seal” Emily has.) What does she decide when it comes to dealing with Emily in the present? What are her reasons for this decision? Do you agree with the mother on this?

- For the mother, what is at stake? Think about how Emily’s wellbeing impacts the mother’s quality of life. The mother arrives at a decision. What does this decision suggest about her resourcefulness and resilience?

- What do you think ironing represents in this story?

- How do you expectations are different today, when it comes to supporting single mothers? In your country, what kind of help can a single mother expect? Which new expectations exist which didn’t exist back then?

SETTING OF “I STAND HERE IRONING”

PERIOD

The ironing part of the story takes place in the 1950s, and the mother reflects on her 19-year-old daughter’s life, starting from birth. So the story begins in the 1930s.

DURATION

About 19 years, over the course of a young woman’s life, summarised.

No class of people experienced more change as a consequence of the [Second World] War than American women.

William H Chafe, author of The American Woman: Her Changing, Social, Economic, and

Political Roles, 1920-1970. London: Oxford University Press. 1972.

LOCATION

In a working class area of 1940s-50s America.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The mother makes use of an iron. Electric irons were first launched in the early 1900s, so it’s likely this mother is using an electric iron, although my own childhood household had one of those old fashioned kinds — heavy and black — which had been inherited from just one generation back. My grandmother used one in her youth, heating it on the nearby oven. The switch from oven-heated to electric powered irons happened in the era Emily grew up, which may be, partly — on a subconscious level — why the task of ironing causes this mother to reflect on her daughter’s life. Things are very different for women in the post war era. How are things different?

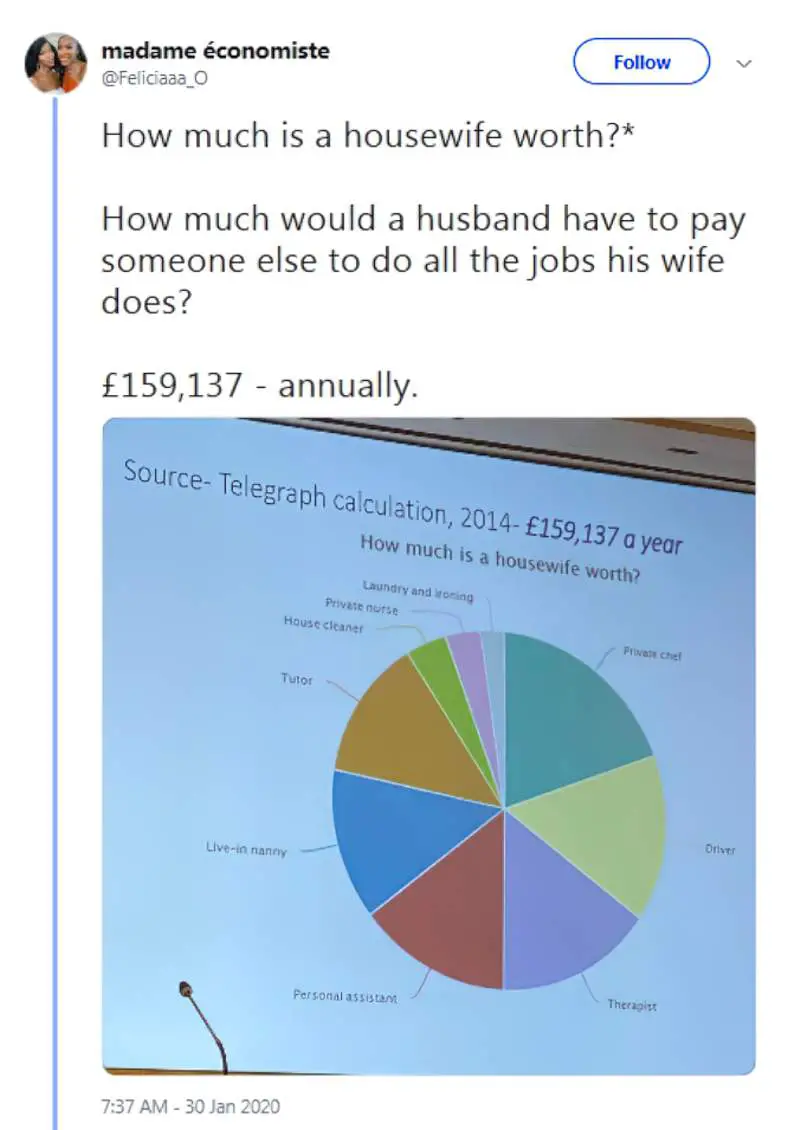

Here’s what 1950s mothers would have noticed: Although an electric iron turns the onerous task of smoothing clothes into a far more meditative one, though mechanisation of washing tasks did not decrease the workload for mothers at all. Mothers were simply expected to keep cleaner houses and cleaner clothes.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

The mid 20th century was an era unto itself — highly unusual compared to all that came before and all that has come after. For the first time, mothers were bringing up large families, and expecting their offspring to make it to adulthood. Previously, families were small because of childhood disease and death.

However, it took decades longer for the work of mothering to be considered work in any sort of compensatory sense — an ongoing battle. If a father suddenly decided he didn’t want to be a parent, he could upsticks and take off and the mother had no social security. But since parenting a young child is, indeed, a full-time job in itself, it’s literally impossible to be a parent and to work outside the home, even if you try to arrange your working hours. Even mothers must sleep.

So the level of conflict in this story is about how mid-century American society treats mothers without husbands. Society imposes an impossible moral dilemma. Hand your child to some second-rate caregiver who will at least keep her alive, or you both starve.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “I STAND HERE IRONING”

This short story is about a community rather than an individual. This mother stands in for mothers in general, especially single mothers. We never learn the mother’s name. When authors choose not to name characters, the reason is sometimes that they don’t want to individuate them unnecessarily, and I believe that’s the reasoning here. (Note that the teacher/counsellor who has made the call is also unnamed.)

As a contemporary comparison, take “Brokeback Mountain” by Annie Proulx. Sure, the characters in Proulx’s story are named (it’s a much longer short story) but “Brokeback Mountain” isn’t about Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar. With flashbacks to a horrific homophobic murder, Proulx elevates her story into a story about hatred with permeates a community.

In the same way, “I Stand Here Ironing” is about how society treats mothers, especially single mothers, and especially single mothers of daughters. The “main character” in such stories is “the community”.

SHORTCOMING

When single mothers are not given the help they need to support their children — emotionally and financially — everyone loses out. In particular, the mother loses out, next her children.

Society had moved away from communal care of children to a model in which mothers are ideally expected to stay in the home with their own children, providing round the clock care while financially supported by a husband.

For the first time in history, mothers were held solely responsible for keeping children alive. Before, if children died, this was thought to be in the hands of God.

It cannot be overestimated the effect this had on mothers. Below is an advertisement for Cream of Wheat, a seemingly benign breakfast food. The mother looks down at her sick little boy, and the copy tells us that she, personally, could very easily kill him. How can a mother kill her darling little boy? By failing to feed him the right amount of Cream of Wheat, introduced into his diet at the right pace. Mothers cannot be trusted to know how to feed their children creamed wheat, but are instead encouraged to ask the advice of their (male) doctors.

A small selection of things 1930s mothers were blamed for:

- If a young man avoided fighting in the war, the mother had been too soft.

- If a mother gave her children too much attention, they would grow up attention-seeking, neurotic and fearful, unable to self-regulate without the mother’s constant soothing.

- If a mother did everything perfectly, her children grew up to be insufferably entitled.

As science advances we learn the importance of maternal health and well-being. Now we know that a mother’s health is important even from before the time of conception. A ‘good’ mother takes folic acid if she means to conceive, and all conception should be on purpose. A ‘good’ pregnant woman avoids cream cheese and soft-serve ice-cream because listeria will kill her baby. A ‘good’ new mother avoids cheap plastic containers, baby wipes, cough medicine and even Bonjela, last I looked at the list of rules. If we give our children peanut butter too young, we might kill them. But if we leave it too late to introduce peanut butter, the child might develop an allergy which might otherwise have been averted… And so on and so forth.

DESIRE

The narrator mother of “I Stand Here Ironing” wants her eldest daughter to have a decent life, with the understanding that ‘decent life’ for Emily may simply mean not being completely ‘flattened’ into a two-dimensional archetypal mother and wife.

OPPONENT

Western society of the early to mid 20th century is wholly against mothers, but under the guise of supporting them. The Ideal Mother was the white middle class mother, and even she wasn’t doing so well.

PLAN

Her whole parenting life, the narrator has scraped by, responding to circumstances rather than making any real choices of her own. When starvation is the alternative, the ‘decision’ to leave Emily in substandard care was really no ‘decision’ at all.

But in this story she does, finally, get to make a decision. Finally, after many years of arduous childcare, she has time to think as she irons with her electric iron, and she decides not to bring in any more outside ‘help’ when it comes to Emily.

Outside help has done neither of them any good. As part of the backstory, the mother tells us she did as the parenting books told her to. Back then, mothers parented according to a schedule set down by the likes of parenting experts (always men). Doctor Spock came along just after Emily’s era and told mothers that they know more than they think they do, which was revolutionary.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Since Tillie Olsen wrote elsewhere that 20th century women were kept in line with the Sisyphean task of housework, mothering and wife-ing, it’s easy to see that idea in this short story. While women were entering the paid labour market at increasing rates through the 1930s, no one was afforded public airspace about what that meant for women with childcare and housework responsibilities.

From a study of magazine articles of the 1930s:

What was most striking in the Great Depression-era magazine articles is what they failed to say about mothers. Despite the unprecedented financial upheaval, the mothers featured in these magazines were stably situated in at least the middle class. Although they might not have household help, they were never someone else’s help.

The magazine mothers went blithely on with their household duties without any need to earn money or even to make sacrifices, and they presumed their readers did the same. Fathers were invisible breadwinners, who rarely appeared and remained voiceless as parents.

Even a brief article entitled “Mothers Need Vacations” recommended that mothers spend a week at a hotel without mentioning whether fathers should come along or what happened to children left at home.

That article not withstanding, magazine mothers rarely ventured outside the home where they wisely but discretely steered their children to make the choices that would shape them into happy, healthy adults.

In fact, virtually all the articles we considered suggested mothers were to solely responsible for whether the child turned out OK. Schools, peers, and the society at large, implied the advertisements and articles in our sample, were powerless against their motherly influence. And they were severely warned against playing the role inappropriately.

Procrustean Motherhood: The Good Mother during Depression (1930s), War (1940s), and Prosperity (1950s)

This short story is also about how lack of societal support has its outworkings in the family, especially between the women in a household — the mother/daughter relationship, the sister/sister relationship. Where respect for personhood is so rare, fraught and hard-won for women, women will turn inwards, against each other.

The daughters of the family don’t get on because neither of them is getting what she needs. Women are taught to blame other women whenever this happens, when care and attention is a precious resource.

Because of all the younger half-siblings that came along, Emily was required to be a little mother, even while still needing mothering herself.

These days we talk about ‘boundaries’, but I believe when Tillie Olsen writes of Emily’s ‘seal’, she is talking about Emily setting her own personal boundaries. No longer to content to do whatever society is asking of her (we never do find out what led to the Concerned Phone Call), Emily has set her own boundaries. She’s simply Not Doing It, whatever ‘it’ is. For the mother, this is a good sign. Her daughter at least has boundaries. She has learned to ‘set her seal’.

ANAGNORISIS

Near the end of the story, readers are encouraged to contemplate the metaphorical significance of the ironing.

First, the act of ironing is a meditative task and provides the mental space for this mother to reflect. This is space she would not ordinarily get, and she tells us this — her thoughts are only just now becoming her own again as her youngest gets to an age where he is not constantly calling out for his mother.

Second, love has manifold expressions. In the case of this harried and consistently overworked, under-resourced mother, the simple act of ironing her 19-year-old daughter’s dress is an expression of love. It’s worth noting that, in the 1940s, a 19-year-old was well-and-truly considered an adult, and mothers did not typically iron their daughters’ clothes for them even if they absolutely would have done washing tasks for their sons. A literary term for how Olsen uses the iron metaphorically in this short story, popularized by T.S. Elliot: The Objective Correlative.

No doubt some readers will have the personal experience of how 20th century mothers routinely treated their sons with more outward signs of love and attention, including in the most practical of ways (cooking for them, expecting less around the house). Alice Munro has written about this dynamic, most obviously in her short story “Forgiveness in Families”, in which an adult daughter must come to terms, somehow, with the reality that the mother will always prefer her mother, despite the brother’s clear lack of reciprocated love.

When this narrator only wishes for Emily that she learns her own worth, rather than be ‘helpless before the iron’, she hopes that the patriarchy and her personal childhood trauma won’t conspire to ‘flatten’ her personhood into that of a dutiful woman.

NEW SITUATION

In “I Stand Here Ironing”, Tillie Olsen writes about how it takes a village to raise a child, but individual mothers are disproportionately expected to take on this immense task, largely unsupported — financially, emotionally and in every other way.

The mother makes the decision not to engage the ‘help’ of the expert on the phone.

- Too little, too late;

- If Emily’s made it this far with her nihilistic sense of humour intact, she can face anything life throws at her;

- Any help offered by this person is piecemeal, when people require wraparound support. Piecemeal support can in fact be worse than useless, especially when it comes from people who don’t know the family. This mother understands full well that in the social milieu of the 1950s, she herself will be disproportionately blamed for Emily’s shortcomings.

- The back and forth motion of the iron mirrors the mother’s back-and-forth thoughts as she considers whether to call the school person back or not.

Ultimately, the mother decides not to call the authority figure back. This the mother’s character arc: She, alone, is the authority figure on her own children. After this much mothering experience, she has seen firsthand how society isn’t going to help her in her mothering role. In this respect, the hot and heavy iron almost functions as a symbolic weapon.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

OLSEN’S PARENTING MESSAGE

Where a mother has numerous children, the health and well-being of the boys will be prioritised, in a system which allows boys to grow up and become breadwinners. That’s where some mothers place their hope. But this particular mother is a role model for 1950s women: You may well have sons too, but don’t lose hope in your daughters. Society pushes them down, but through this process, just hope she has built some resilience.

A HAPPY ENDING

Ultimately, I believe this story ends on a high note. We’ve seen Emily stand up for herself. Unlike her mother, this young woman at least has some agency. WW2 came along and changed up the gender dynamics. Whereas the 1950s was all about forcing women back into the domestic sphere after their important wartime contributions in the paid labour market, feminists like Tillie Olsen could no doubt see that something had changed permanently, and the younger generation of women would not be put back into the box.

Emily’s life won’t be easy, but intervention from a Professional Helper would not have made the young woman’s life any easier, and may quite possibly have made her life worse. I can imagine Emily taking part in the social movements of the 1960s.

RESONANCE

Until we have a universal basic income, this crap will continue. There was a brief period towards the end of the 20th century where social security really did look after mothers in a real, financial way. Single mothers have always raced social discrimination, make no mistake, but to focus on my home country of Australia for a moment, the economic support for single parents (who are overwhelmingly women) is nowhere near what it once was in real terms.

SOCIAL SECURITY IN THE AGE OF LATE CAPITALISM

This was pointed out when Anthony Albanese was elected Prime Minister. In his acceptance speech, Albanese talked about what a great country Australia is, when a single mother on benefits can bring up a son who one day becomes Prime Minister. Albanese has mentioned his roots many times.

Others have pointed out that, were Anthony Albanese born under identical conditions today, he would not have anywhere near the same opportunities as his own childhood self. This is largely due to the changes in social housing:

While there is still stigma [against single mothers], it’s milder than what existed in the 1960s and 1970s, when Maryanne was raising a future prime minister who had been told his very-much-alive father had died. But just as society was different, so was the Australian welfare state.

Albanese grew up in the same home where Maryanne had been born in 1936. He has spoken of his first campaign against a push to sell off his home. He was still a boy; the campaign was a success.

If they had been evicted, it is likely the family would not have faced the long waits that are common for those seeking social housing today.

Sinclair and her two boys waited four years for access to public housing, while research suggests some wait as many as 10 years, if not much longer.

Single mothers hope Anthony Albanese’s upbringing might spur change, The Guardian, May 2022

Has the situation improved for mothers since the 1930s?

Women are disproportionately burdened with the task of keeping children healthy, attending doctors’ appointments, seeking out diagnoses, managing children’s pain, interacting with school teachers, volunteering at schools and so on.

And when a child experiences poor health, neurodivergence or otherwise needs an extra level of care, then all of those old 1930s tropes will come back to bite her.

It’s there all along, just under the surface: “Mum is anxious.”

Fiction such as “I Stand Here Ironing” is super important because it fills a very important role: Only when women understand the systemic injustice at work can they step back from self-blame. This, I believe, is what Tillie Olsen aimed for with this short story, and I think it’s a marvellous feminist work.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

I Stand Here Ironing by Tillie Olsen (US, 1961) — an audio recording

In this episode, we discuss “I Stand Here Ironing” by Tillie Olsen. What can we learn from this timeless story? How can a situation drive a story? What does the structure of the story provide for the overall effect? What does that structure require, and how can we apply those necessities to other stories? How important is narrative movement to a story?

Why Is This Good? podcast

The Big Choice — “I Stand Here Ironing” discussed at the Story Grid podcast

Shawn Coyne of The Story Grid calls this short story a “Status Story”, meaning “a single protagonist’s quest to rise in social standing and the price he or she must pay in order to do so.” To what extent do we go for to earn the respect of some third party?

The woman editors immediately identify with the main character and consider the story a mea culpa. She’s simply doing what she can to raise this child. She feels heartbroken rather than guilty.