Detective stories are as old as police detectives themselves. Unless we count Oedipus as a detective story, the oldest popular detective story is often said to be “The Murders In The Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe (1841). While Charles Dickens isn’t best known for his detective stories, true crime was a serious hobby. He knew a lot about how British police were doing their work, and even shadowed them as they went about their days.

“Hunted Down” was published in instalments across 1859-60, almost 20 years after Poe’s detective story. This allowed time for the subgenre to have kicked off in earnest. Detective mysteries have never stopped being popular, and are today the most successful shows on TV.

So, “Hunted Down” is a crime story, but it is also a dark transgression comedy, which turns into slapstick near the end.

This isn’t an intuitive link, but transgression comedies and thrillers share a story structure in common: A character tries to get away with something and is eventually unmasked.

- Discontent: someone is unhappy about something

- Transgression with a mask: peculiar to comedy (and, incidentally, to noir thrillers)

- Transgression without a mask: midpoint disaster when the mask is ripped off

- Dealing with consequences

- Spiritual Crisis: happens in almost every story but the con man in this one is unrepentant

- Growth Without a Mask

Dickens wrote this story before most readers had even thought of ‘insurance fraud’ as a crime possibility. Pick-pocketing? Yes. Breaking and entering? Sure, everyone understood those. But insurance fraud wasn’t really the realm of the genuinely poor; this is white collar crime, and I imagine it carried the same sense of awe and cleverness as cybercrime does to contemporary readers (most of whom wouldn’t have the first clue of how to go about doing cybercrime). The fraudster in this story is well-dressed, well-spoken and suspiciously ingratiating. The modern reader will predict the nature of the crime early in the story, probably as soon as we learn the narrator sells life insurance.

Unusually, though, Dickens’ insurance broker subsequently embarks upon detective work himself. Got to admit, even today you don’t see many fictional insurance brokers solving crimes. Retired ladies? Yes. Computer hackers? More yes. By my reckoning, when it comes to contemporary works, the insurance salesman is more likely to be the one murdered than crime fighting.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

(Please note, simply listing the cast of this story will contains spoilers.)

MR SAMPSON

The first person narrator. A life insurance broker who turns temporarily into a detective, helping to save the life of a young woman about to be poisoned.

JULIUS SLINKTON

The con man of the story. A poisoner and white collar criminal who dresses in finery and goes about poisoning people after taking out life insurance on them. Is he the blood relative of Miss Niner? I don’t know — didn’t older men used to gad about in the company of young women by telling everyone he was the uncle?

Dickens presents him as an effeminate character. It’s worth pointing that out characters (and people) who transgress gender are historically mistrusted. Slinkton wears clothes which are pretty; too pretty. His manners are nice; too nice. He accommodates; he is too accommodating.

Each of these attributes would be expected of a woman, but because he’s a man, this makes him non-gender conforming. Gender non-conformist as untrustworthy criminal is in Dickens’ toolbox. By creating a man who doesn’t conform to gender, he presents Slinkton as unreliable in general. Appearances deceive; anything other than complete conformity to the gender binary is a deception.

Unless you notice the storytelling pattern, this characterisation may be too subtle to notice. Slinkton is not presented as trans, but trans people get such a raw deal in fiction. Transphobia is the water we’re swimming in, and it is the police force which kicks in for all of us, as soon as we step outside the bounds of compulsory binary gender.

Slinkton’s effeminate, gender non-conforming unreliability is a part of the Gothic clergy archetype, by the way, and Slinkton is thought to pass for a clergyman. The fact that this problematic trope is an established archetype doesn’t cancel out the problem with it.

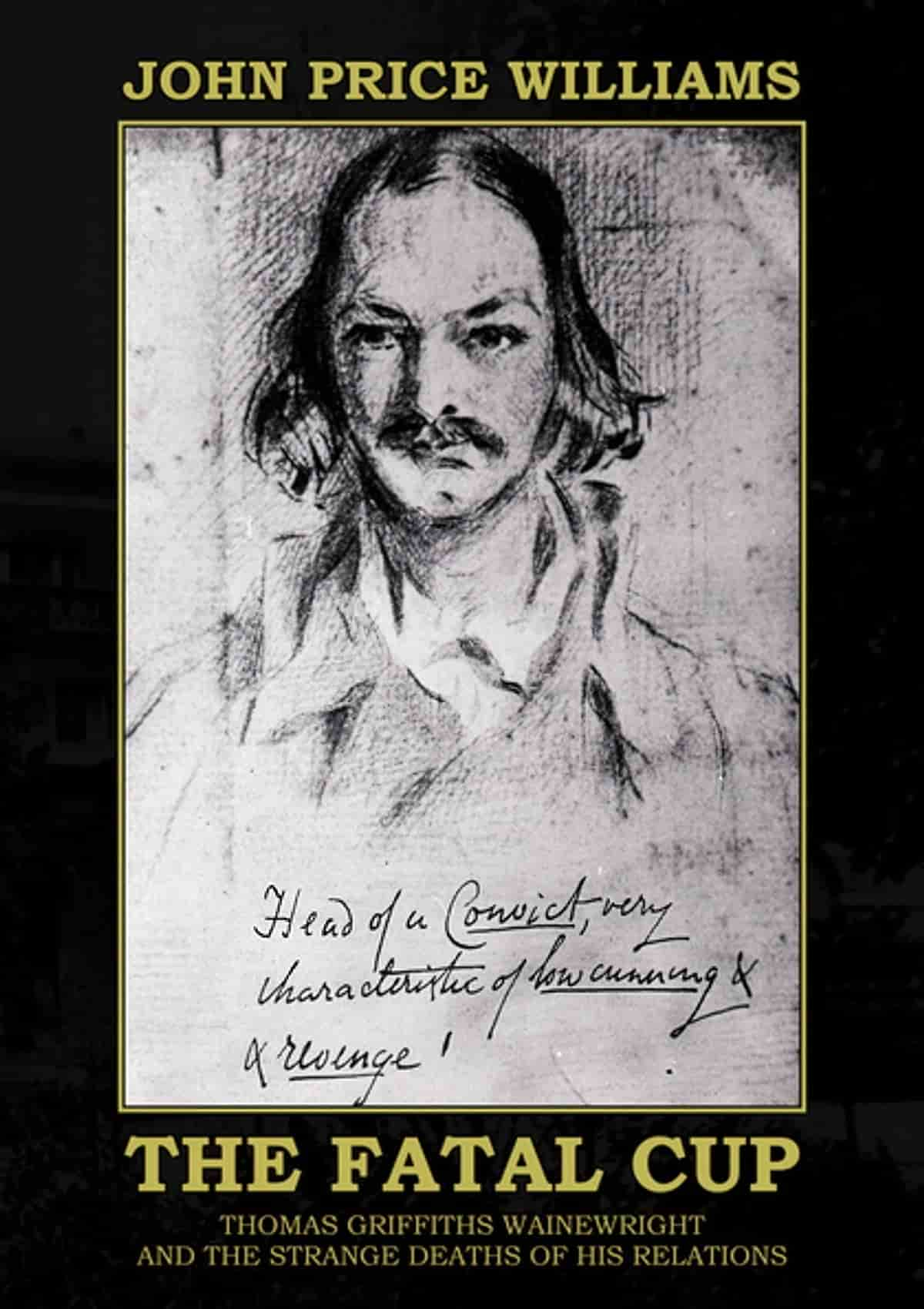

It’s thought that Slinkton is the fictional version real-life suspected poisoner Thomas Griffiths Wainewright. He was called a dandy at the time. He was born in 1794, and was among the criminals sent out here to Australia (specifically to Tasmania, where we can guarantee he would not have had fun). He died at the age of 52.

Part of the reason Dickens was paid handsomely for this story was because of the public enthusiasm for more information on this man, and if they couldn’t have information, they’d settle for a thinly disguised fictional version.

Dickens was also interested in an insurance criminal called Dr. William Palmer. His media name was The Rugely Poisoner. During his trial, he fiddled with his gloves the whole way through. You’ll notice in this story the emphasis on gloves. Other than that, William Palmer was calm, cool and collected.

MISS MARGARET NINER

A woman in her early twenties, about to be saved by the narrator by her predatory “uncle”, Julius Slinkton.

THE DEAD MISS NINER

Miss Niner’s sister is already dead. Poisoned. By Mr Slinkton, who has collected on her life insurance and is moving on to his next victim from the same family.

ALFRED BECKWITH A.K.A. MAJOR BANKS, real name meltham

The dupe of the story. The dupe’s role is to trick con artists into revealing themselves. And in satisfying narratives, con artists must reveal themselves. The unmasking part is a necessary part of the transgression story structure.

This week, Cara is joined by Maria Konnikova, the author of “The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It…Every Time.” They discuss the art of the con artist (including whether Donald Trump fits the bill) as well as Maria’s unique approach to writing, merging psychology and literature.

Con Artists w/ Maria Konnikova

Meltham is the character who gives Julius Slinkton a big surprise. He’s an actuary called Meltham.

A talented actuary around the age of 30 who has disappeared without notice from his regular traps. What’s his stake in all this? He’s the former beau of the dead Miss Niner. Now he aims to save his lover’s sister and bring the poisoner to justice.

In order to catch the poisoner, he’s been posing as two different men, following him around. In London he’s Mr Beckwith, but while Miss Niner is on holiday in Scarborough he poses as an invalid called Major Banks.

Why an invalid? He wants to trick Slinkton into thinking he’s almost dead, and a good target.

“Hunted Down” Annotated

Most of us see some romances in life. In my capacity as Chief Manager of a Life Assurance Office, I think I have within the last thirty years seen more romances than the generality of men, however unpromising the opportunity may, at first sight, seem.

‘Most of us’. It’s not often you see in fiction the acknowledgement that most — but not everyone — is romantic. Was 1860 less amatonormative than the present day? But honestly, by the time this story cranks up, I’ve forgotten it started with a romance.

As I have retired, and live at my ease, I possess the means that I used to want, of considering what I have seen, at leisure. My experiences have a more remarkable aspect, so reviewed, than they had when they were in progress. I have come home from the Play now, and can recall the scenes of the Drama upon which the curtain has fallen, free from the glare, bewilderment, and bustle of the Theatre.

This guy is telling us he’s had time to reflect on events which happened long ago. This mode of narration is quite different from a more immediate retelling by an intradiegetic character. Not every story is so on-the-page about this, though. He thinks of the past as a play which he once saw, and he’s trying to persuade us that he’s about to recount a story in which he is an objective observer rather than a subjective participant. (He doth protest too much?) As a contemporary reader I smell ‘unreliable narrator’ at this point, but that is not what Dickens was going for at all. As the story progresses, we learn that Dickens has been working hard to establish his narrator as a reliable cataloguer of fact.

Let me recall one of these Romances of the real world.

‘Real world’? So there’s another, supernatural realm…? Nope, this is not a supernatural story. Perhaps ‘real world’ refers to the ‘world of crime’, of which most of us know little.

There is nothing truer than physiognomy, taken in connection with manner. The art of reading that book of which Eternal Wisdom obliges every human creature to present his or her own page with the individual character written on it, is a difficult one, perhaps, and is little studied. It may require some natural aptitude, and it must require (for everything does) some patience and some pains. That these are not usually given to it,—that numbers of people accept a few stock commonplace expressions of the face as the whole list of characteristics, and neither seek nor know the refinements that are truest,—that You, for instance, give a great deal of time and attention to the reading of music, Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Hebrew, if you please, and do not qualify yourself to read the face of the master or mistress looking over your shoulder teaching it to you,—I assume to be five hundred times more probable than improbable. Perhaps a little self-sufficiency may be at the bottom of this; facial expression requires no study from you, you think; it comes by nature to you to know enough about it, and you are not to be taken in.

Okay, so physiognomy is a form of bigotry and lookism popularly practised in the 1800s, and was used to prop up and promote racism. Basically, physiognomy is the act of using physical features to determine a person’s character or personality. It goes back to Plato and Ancient China, but was especially popular in the Victorian era.

Physiognomy and phrenology are what are now known as pseudosciences, but during the Victorian era, they were taken as seriously as the laws of physics are today. References to both were made throughout the artifacts they left behind, including novels such as David Copperfield.

Rebecca Mitchell

Mitchell describes how the use of phrenology and physiognomy in Dickens’ 1949-50 novel David Copperfield turns out to be useful in determining a character’s personality and character traits. So it is here.

I confess, for my part, that I have been taken in, over and over again. I have been taken in by acquaintances, and I have been taken in (of course) by friends; far oftener by friends than by any other class of persons. How came I to be so deceived? Had I quite misread their faces?

“Don’t ever trust your friends.” Seriously, are we being gas-lit here? (That is not Dickens’ intention, as the story later reveals.)

No. Believe me, my first impression of those people, founded on face and manner alone, was invariably true. My mistake was in suffering them to come nearer to me and explain themselves away.

The only person you can trust is me, who has learned from my mistakes. If Dickens had been familiar with the pattern of coercive control (which I’m sure goes back centuries), I’m confident he’d have skipped this paragraph, too, since he means his narrator to sound reliable.

CHAPTER TWO

The partition which separated my own office from our general outer office in the City was of thick plate-glass. I could see through it what passed in the outer office, without hearing a word. I had it put up in place of a wall that had been there for years,—ever since the house was built. It is no matter whether I did or did not make the change in order that I might derive my first impression of strangers, who came to us on business, from their faces alone, without being influenced by anything they said. Enough to mention that I turned my glass partition to that account, and that a Life Assurance Office is at all times exposed to be practised upon by the most crafty and cruel of the human race.

The City refers to a small area in London where, historically, privileged white men go to make lots of money for themselves and for others like them.

This guy is an insurance broker. ‘Life assurance’, often known as a whole of life policy, is a type of insurance that continues indefinitely and pays out a lump sum once a policyholder dies (assuming they’ve met their monthly payments).

Many people think their own line of work affords special insight into human nature. This guy is one of them. (I’d argue that any public facing job affords its own special collection of insights into human nature.) I trust he’s right in that life assurance puts you in contact with a particular kind of criminal, and in 1860, there weren’t the checks and balances to stop people taking out life insurance on loved ones then immediately knocking them off.

It was through my glass partition that I first saw the gentleman whose story I am going to tell.

Like the theatre curtain he mentioned earlier, emphasis on this glass partition is an attempt to persuade readers of the narrator’s objectivity. He sees ‘clearly’ but also from a slightly removed, more objective vantage point.

He had come in without my observing it, and had put his hat and umbrella on the broad counter, and was bending over it to take some papers from one of the clerks. He was about forty or so, dark, exceedingly well dressed in black,—being in mourning,—and the hand he extended with a polite air, had a particularly well-fitting black-kid glove upon it. His hair, which was elaborately brushed and oiled, was parted straight up the middle; and he presented this parting to the clerk, exactly (to my thinking) as if he had said, in so many words: ‘You must take me, if you please, my friend, just as I show myself. Come straight up here, follow the gravel path, keep off the grass, I allow no trespassing.’

Stories frequently work on the cognitive bias that people who are handsome and well-dressed must therefore be good people.

This shady character is relying upon people judging him on his dress (which he probably ripped from the dead bodies of rich guys, as we later learn).

Can you think of a fairytale character who does this? I’m thinking of Puss In Boots.

Our narrator believes himself smarter than the regular Joe Blow because he fancies his work affords extra insight into human nature. Bwahaha. That’s exactly what a privileged Victorian white guy would say, isn’t it? Tell you what, if I could travel back in time to get a handle on the ‘real’ shady characters of Victorian London, I’d ask sex workers.

I conceived a very great aversion to that man the moment I thus saw him.

Because he’s good at reading faces, you see. Because physiognomy.

He had asked for some of our printed forms, and the clerk was giving them to him and explaining them. An obliged and agreeable smile was on his face, and his eyes met those of the clerk with a sprightly look. (I have known a vast quantity of nonsense talked about bad men not looking you in the face. Don’t trust that conventional idea. Dishonesty will stare honesty out of countenance, any day in the week, if there is anything to be got by it.)

We put too much stock in eye-contact, as any neurodivergent person will happily tell you. Interesting just how long this conversation has been going on. At one point in ‘human’ history, we stared each other down as an invitation to fight. I guess we’ll be talking about the so-called importance of eye-contact for at least another few hundred years, even though it’s no more reliable than physiognomy. This narrator understands the futility of judging by eye-contact but can’t see the futility of judging by skull shape. Unintended irony.

I saw, in the corner of his eyelash, that he became aware of my looking at him. Immediately he turned the parting in his hair toward the glass partition, as if he said to me with a sweet smile, ‘Straight up here, if you please. Off the grass!’

“In the corner of his eyelash” is an interesting turn of phrase. If you Google it, this very story comes up in all the top search results so the phrase is either a neologism for this work, or was an English idiom which died long before the Internet existed.

In a few moments he had put on his hat and taken up his umbrella, and was gone.

I beckoned the clerk into my room, and asked, ‘Who was that?’

He had the gentleman’s card in his hand. ‘Mr. Julius Slinkton, Middle Temple.’

‘A barrister, Mr. Adams?’

‘I think not, sir.’

Hats often signal that someone is pretending to be someone they’re not. When we wear a certain hat we wear a certain identity. Umbrellas, too, can subliminally suggest obfuscation and are also reminiscent of a bat, flying in and out under the cloak of darkness, with vampiric associations of parasitism. Remember, this guy is dressed all in black, presumably because he’s sad about losing someone. This also makes him a Grim Reaper archetype. As we’ll learn later, Slinkton is the last person dead people have formed a relationship with.

p.s. ‘Slinkton’ is precisely the kind of aptronym Dickens is famous for.

He had the gentleman’s card in his hand. ‘Mr. Julius Slinkton, Middle Temple.’

‘A barrister, Mr. Adams?’

‘I think not, sir.’

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray’s Inn and Lincoln’s Inn. It is located in the wider Temple area of London, near the Royal Courts of Justice, and within the City of London.

‘I should have thought him a clergyman, but for his having no Reverend here,’ said I.

‘Probably, from his appearance,’ Mr. Adams replied, ‘he is reading for orders.’

I should mention that he wore a dainty white cravat, and dainty linen altogether.

‘What did he want, Mr. Adams?’

‘Merely a form of proposal, sir, and form of reference.’

‘Recommended here? Did he say?’

“Reading for orders”: The historic practice of a bishop tutoring a candidate himself.

I’m interested in this use of ‘altogether’ as it seems to refer to a type of clothing, but in relation to clothing, can only find the idiomatic phrase ‘in the altogether’, meaning naked, of course. A search for ‘linen altogether’ returns contemporary women’s one-piece dresses, so I imagine an ‘altogether’ describes any sort of clothing which covers the whole body. Old line drawings by illustrators of this story confirm my guess.

‘Yes, he said he was recommended here by a friend of yours. He noticed you, but said that as he had not the pleasure of your personal acquaintance he would not trouble you.’

‘Did he know my name?’

‘O yes, sir! He said, “There is Mr. Sampson, I see!”’

‘A well-spoken gentleman, apparently?’

‘Remarkably so, sir.’

‘Insinuating manners, apparently?’

‘Very much so, indeed, sir.’

‘Hah!’ said I. ‘I want nothing at present, Mr. Adams.’

It’s a little unsettling when someone knows you but you don’t know them.

This is the first time we learn the narrator’s name: Mr Sampson.

Insinuating: using subtle manipulation to manoeuvre oneself into a favourable position.

Within a fortnight of that day I went to dine with a friend of mine, a merchant, a man of taste, who buys pictures and books, and the first man I saw among the company was Mr. Julius Slinkton. There he was, standing before the fire, with good large eyes and an open expression of face; but still (I thought) requiring everybody to come at him by the prepared way he offered, and by no other.

Now there’s a coincidence.

Large eyes are, by the laws of physignomy, trustworthy eyes. I’m sure this has something to do with how we react to babies. Babies are ‘innocent’; babies have large eyes in proportion to their heads. (How did people not think to question this ‘science’?)

I noticed him ask my friend to introduce him to Mr. Sampson, and my friend did so. Mr. Slinkton was very happy to see me. Not too happy; there was no over-doing of the matter; happy in a thoroughly well-bred, perfectly unmeaning way.

In some cultures it’s still rude to talk to someone directly until after you’ve been formally introduced by the mutual acquaintance (e.g. Japan).

‘I thought you had met,’ our host observed.

‘No,’ said Mr. Slinkton. ‘I did look in at Mr. Sampson’s office, on your recommendation; but I really did not feel justified in troubling Mr. Sampson himself, on a point in the everyday routine of an ordinary clerk.’

I said I should have been glad to show him any attention on our friend’s introduction.

‘I am sure of that,’ said he, ‘and am much obliged. At another time, perhaps, I may be less delicate. Only, however, if I have real business; for I know, Mr. Sampson, how precious business time is, and what a vast number of impertinent people there are in the world.’

I acknowledged his consideration with a slight bow. ‘You were thinking,’ said I, ‘of effecting a policy on your life.’

‘O dear no! I am afraid I am not so prudent as you pay me the compliment of supposing me to be, Mr. Sampson. I merely inquired for a friend. But you know what friends are in such matters. Nothing may ever come of it. I have the greatest reluctance to trouble men of business with inquiries for friends, knowing the probabilities to be a thousand to one that the friends will never follow them up. People are so fickle, so selfish, so inconsiderate. Don’t you, in your business, find them so every day, Mr. Sampson?’

Although Mr Slinkton is one whisker away from creep-stalking our narrator Mr Sampson, he makes out he would never want to bother an important businessman, no, not in a million years!

Then he finds a common ground: Aren’t people fickle and annoying. Oh yes, aren’t they just. Not you and me, though.

I was going to give a qualified answer; but he turned his smooth, white parting on me with its ‘Straight up here, if you please!’ and I answered ‘Yes.’

‘I hear, Mr. Sampson,’ he resumed presently, for our friend had a new cook, and dinner was not so punctual as usual, ‘that your profession has recently suffered a great loss.’

‘In money?’ said I.

He laughed at my ready association of loss with money, and replied, ‘No, in talent and vigour.’

Not at once following out his allusion, I considered for a moment. ‘Has it sustained a loss of that kind?’ said I. ‘I was not aware of it.’

‘Understand me, Mr. Sampson. I don’t imagine that you have retired. It is not so bad as that. But Mr. Meltham—’

‘O, to be sure!’ said I. ‘Yes! Mr. Meltham, the young actuary of the “Inestimable.”’

‘Just so,’ he returned in a consoling way.

‘He is a great loss. He was at once the most profound, the most original, and the most energetic man I have ever known connected with Life Assurance.’

We’ll never truly know whether the narrator was always suspicious of this guy, or is suspicious mostly in hindsight, after learning the true nature of him. When we’ve been had, it’s tempting to imagine we were suspicious all along. By the time he writes this story down, he’s bigging his own self up regarding his insights into face reading.

Now the guy’s cracking on he’s not interested in money.

The first mention of Mr Meltham. Dickens is doing that writerly thing where you introduce a character by having other characters talk about him. This makes the readers want to know more, and is one tool in creating suspense. We also have our attention piqued by the time he does appear on the page.

I spoke strongly; for I had a high esteem and admiration for Meltham; and my gentleman had indefinitely conveyed to me some suspicion that he wanted to sneer at him. He recalled me to my guard by presenting that trim pathway up his head, with its internal ‘Not on the grass, if you please—the gravel.’

‘You knew him, Mr. Slinkton.’

‘Only by reputation. To have known him as an acquaintance or as a friend, is an honour I should have sought if he had remained in society, though I might never have had the good fortune to attain it, being a man of far inferior mark. He was scarcely above thirty, I suppose?’

‘About thirty.’

‘Ah!’ he sighed in his former consoling way. ‘What creatures we are! To break up, Mr. Sampson, and become incapable of business at that time of life!—Any reason assigned for the melancholy fact?’

(‘Humph!’ thought I, as I looked at him. ‘But I WON’T go up the track, and I WILL go on the grass.’)

Some people just have really irritating hairstyles, don’t they? In England, if you visit certain tourist attractions (e.g. the grounds at Oxford University) only the important people who belong to the institution are permitted to walk across the carefully manicured grass. All the other plebs must keep to the path. (Coming from New Zealand, where grass is frequently manicured but not especially revered, this way of categorising people felt super weird to me.)

‘What reason have you heard assigned, Mr. Slinkton?’ I asked, point-blank.

‘Most likely a false one. You know what Rumour is, Mr. Sampson. I never repeat what I hear; it is the only way of paring the nails and shaving the head of Rumour. But when you ask me what reason I have heard assigned for Mr. Meltham’s passing away from among men, it is another thing. I am not gratifying idle gossip then. I was told, Mr. Sampson, that Mr. Meltham had relinquished all his avocations and all his prospects, because he was, in fact, broken-hearted. A disappointed attachment I heard,—though it hardly seems probable, in the case of a man so distinguished and so attractive.’

‘Attractions and distinctions are no armour against death,’ said I.

More deflection: “Most likely a false one.” Slinkton knows she’s been murdered, since he did it, but now he puts it to our storyteller narrator that the ‘false rumour’ involves the shameful state of heartbreak.

‘O, she died? Pray pardon me. I did not hear that. That, indeed, makes it very, very sad. Poor Mr. Meltham! She died? Ah, dear me! Lamentable, lamentable!’

I still thought his pity was not quite genuine, and I still suspected an unaccountable sneer under all this, until he said, as we were parted, like the other knots of talkers, by the announcement of dinner:

We learn later that Mr Slinkton knows full well his lover died. Because, ya know, he moidered her.

‘Mr. Sampson, you are surprised to see me so moved on behalf of a man whom I have never known. I am not so disinterested as you may suppose. I have suffered, and recently too, from death myself. I have lost one of two charming nieces, who were my constant companions. She died young—barely three-and-twenty; and even her remaining sister is far from strong. The world is a grave!’

Not yet obvious, but another non-coincidence. Mr Meltham’s lover and Slinkton’s niece are one and the same person. And yes, the world is a grave when you go around killing everyone. (Dark comedy.)

He said this with deep feeling, and I felt reproached for the coldness of my manner. Coldness and distrust had been engendered in me, I knew, by my bad experiences; they were not natural to me; and I often thought how much I had lost in life, losing trustfulness, and how little I had gained, gaining hard caution. This state of mind being habitual to me, I troubled myself more about this conversation than I might have troubled myself about a greater matter. I listened to his talk at dinner, and observed how readily other men responded to it, and with what a graceful instinct he adapted his subjects to the knowledge and habits of those he talked with. As, in talking with me, he had easily started the subject I might be supposed to understand best, and to be the most interested in, so, in talking with others, he guided himself by the same rule. The company was of a varied character; but he was not at fault, that I could discover, with any member of it. He knew just as much of each man’s pursuit as made him agreeable to that man in reference to it, and just as little as made it natural in him to seek modestly for information when the theme was broached.

In linguistics, this ability is called ‘accommodation’. We all do it as we move from one social situation to another. (If we can’t accommodate, we don’t get on very well in life.)

As he talked and talked—but really not too much, for the rest of us seemed to force it upon him—I became quite angry with myself. I took his face to pieces in my mind, like a watch, and examined it in detail. I could not say much against any of his features separately; I could say even less against them when they were put together. ‘Then is it not monstrous,’ I asked myself, ‘that because a man happens to part his hair straight up the middle of his head, I should permit myself to suspect, and even to detest him?’

It’s amazing how hair partings go in and out of fashion. We even imbue binarist opinions on which is the feminine and which is the masculine side to part one’s hair. For the first fifteen years of the 2000s, side parts were definitely the go But Gen Z are apparently going back to the straight centre part. It makes someone appear more serious. This narrator chides himself for judging someone on how they part their hair, but he clearly isn’t the only one to do this.

Is all this Internet talk about hair partings a modern take on physiognomy? The only minor difference is that people choose (somewhat) where to part their hair, whereas facial characteristics are not chosen.

(I may stop to remark that this was no proof of my sense. An observer of men who finds himself steadily repelled by some apparently trifling thing in a stranger is right to give it great weight. It may be the clue to the whole mystery. A hair or two will show where a lion is hidden. A very little key will open a very heavy door.)

The narrator describes the difference between relying on instinct (beneficial and necessary) vs relaxing into stereotyping and learned bigotry. People who’ve put a lot of thought into not being bigots can sometimes mistrust their own intuitions about bad people, something Gavin de Becker cautions against in his book The Gift of Fear. Both are necessary, insofar as ‘intuition’ is the sum total of (sublimated) life experience.

I took my part in the conversation with him after a time, and we got on remarkably well. In the drawing-room I asked the host how long he had known Mr. Slinkton. He answered, not many months; he had met him at the house of a celebrated painter then present, who had known him well when he was travelling with his nieces in Italy for their health. His plans in life being broken by the death of one of them, he was reading with the intention of going back to college as a matter of form, taking his degree, and going into orders. I could not but argue with myself that here was the true explanation of his interest in poor Meltham, and that I had been almost brutal in my distrust on that simple head.

When Slinkton travelled through Italy with his nieces ‘for their health’ it’s quite likely he’d been poisoning them for ages already, which is why their health was so poor. Guy got a free trip to Italy out of it, as well as collecting on her life insurance.

The narrator starts to doubt himself when he hears Meltham intends to join the church. The church has long conferred trustworthiness upon anyone who wishes to use religion as cover for evildoing, and as a consequence attracts evildoers.

CHAPTER THREE

On the very next day but one I was sitting behind my glass partition, as before, when he came into the outer office, as before. The moment I saw him again without hearing him, I hated him worse than ever.

Seems a bit abrupt, considering last chapter he was trying to be friendly with the guy. What the hell happened?

It was only for a moment that I had this opportunity; for he waved his tight-fitting black glove the instant I looked at him, and came straight in.

‘Tight-fitting’ suggests he murdered the person who used to own it. (Perhaps it is small because it is a woman’s glove? Unclear.)

‘Mr. Sampson, good-day! I presume, you see, upon your kind permission to intrude upon you. I don’t keep my word in being justified by business, for my business here—if I may so abuse the word—is of the slightest nature.’

I asked, was it anything I could assist him in?

‘Obsequious’ is the word to use here. Like Mr Collins in Pride and Prejudice, his over-the-top attempts at humility only serve to highlight an ulterior motive. (Though as far as I know, Mr Collins wasn’t a murderer. I’d read that adaptation, though.)

‘I thank you, no. I merely called to inquire outside whether my dilatory friend had been so false to himself as to be practical and sensible. But, of course, he has done nothing. I gave him your papers with my own hand, and he was hot upon the intention, but of course he has done nothing. Apart from the general human disinclination to do anything that ought to be done, I dare say there is a specialty about assuring one’s life. You find it like will-making. People are so superstitious, and take it for granted they will die soon afterwards.’

‘Up here, if you please; straight up here, Mr. Sampson. Neither to the right nor to the left.’ I almost fancied I could hear him breathe the words as he sat smiling at me, with that intolerable parting exactly opposite the bridge of my nose.

‘There is such a feeling sometimes, no doubt,’ I replied; ‘but I don’t think it obtains to any great extent.’

‘Well,’ said he, with a shrug and a smile, ‘I wish some good angel would influence my friend in the right direction. I rashly promised his mother and sister in Norfolk to see it done, and he promised them that he would do it. But I suppose he never will.’

He spoke for a minute or two on indifferent topics, and went away.

Dilatory: Slow to act, but in a deliberate way, in order to cause some kind of obstruction.

Dickens is using ‘straightness’ as a motif, first in the centre-part of the crooked man’s hair (the ‘crook’), now underscoring the imagery in an instruction from the crook who visits him at his office, demanding the life insurance be put into place.

I had scarcely unlocked the drawers of my writing-table next morning, when he reappeared. I noticed that he came straight to the door in the glass partition, and did not pause a single moment outside.

‘Can you spare me two minutes, my dear Mr. Sampson?’

‘By all means.’

‘Much obliged,’ laying his hat and umbrella on the table; ‘I came early, not to interrupt you. The fact is, I am taken by surprise in reference to this proposal my friend has made.’

‘Has he made one?’ said I.

Notice again the use of ‘straight’.

‘Ye-es,’ he answered, deliberately looking at me; and then a bright idea seemed to strike him—‘or he only tells me he has. Perhaps that may be a new way of evading the matter. By Jupiter, I never thought of that!’

Mr. Adams was opening the morning’s letters in the outer office. ‘What is the name, Mr. Slinkton?’ I asked.

‘Beckwith.’

I looked out at the door and requested Mr. Adams, if there were a proposal in that name, to bring it in. He had already laid it out of his hand on the counter. It was easily selected from the rest, and he gave it me. Alfred Beckwith. Proposal to effect a policy with us for two thousand pounds. Dated yesterday.

‘From the Middle Temple, I see, Mr. Slinkton.’

‘Yes. He lives on the same staircase with me; his door is opposite. I never thought he would make me his reference though.’

‘It seems natural enough that he should.’

‘Seemed to’. This is a rehearsed conversation, replete with a rehearsed epiphany.

This is the first mention of the name Beckwith. We later learn that this is the fake name of the guy who went missing. He’s tricking Slinkton into thinking he’s about to die.

‘Quite so, Mr. Sampson; but I never thought of it. Let me see.’ He took the printed paper from his pocket. ‘How am I to answer all these questions?’

‘According to the truth, of course,’ said I.

‘O, of course!’ he answered, looking up from the paper with a smile; ‘I meant they were so many. But you do right to be particular. It stands to reason that you must be particular. Will you allow me to use your pen and ink?’

‘Certainly.’

‘And your desk?’

‘Certainly.’

Even though the con man asks permission to use the narrator’s pen and desk; even though this is a natural request in an office where documents must be signed, it feels somewhat like a theft of identity. This con man can’t help but worm his way into other people’s skins, using their accoutrements, wearing their clothes, taking their money.

He had been hovering about between his hat and his umbrella for a place to write on. He now sat down in my chair, at my blotting-paper and inkstand, with the long walk up his head in accurate perspective before me, as I stood with my back to the fire.

This guy, and his suspicious centre part!

Before answering each question he ran over it aloud, and discussed it. How long had he known Mr. Alfred Beckwith? That he had to calculate by years upon his fingers. What were his habits? No difficulty about them; temperate in the last degree, and took a little too much exercise, if anything. All the answers were satisfactory. When he had written them all, he looked them over, and finally signed them in a very pretty hand. He supposed he had now done with the business. I told him he was not likely to be troubled any farther. Should he leave the papers there? If he pleased. Much obliged. Good-morning.

If you’ve ever filled out insurance forms you’ll know the invasive questions they ask. They’re basically wanting to calculate when you’re likely to die. If you lie on the forms, insurance companies don’t have to pay out. It’s all grim business.

I had had one other visitor before him; not at the office, but at my own house. That visitor had come to my bedside when it was not yet daylight, and had been seen by no one else but by my faithful confidential servant.

What the hell. If I ever wake up in the morning to find a stranger standing right next to my bed, I’ll be having words with the ‘faithful and confidential ‘servant. (What did the servant think the visitor was there for? “Oh sure, go right on in, the boss has morning bedroom visitors all the time…”)

A second reference paper (for we required always two) was sent down into Norfolk, and was duly received back by post. This, likewise, was satisfactorily answered in every respect. Our forms were all complied with; we accepted the proposal, and the premium for one year was paid.

Wait, what? He’s not going to tell us who WAS CREEPING RIGHT NEXT TO HIS BED LIKE EDWARD FREAKING CULLEN? We have to end the chapter with boring crap about paperwork in the post?

CHAPTER FOUR

For six or seven months I saw no more of Mr. Slinkton. He called once at my house, but I was not at home; and he once asked me to dine with him in the Temple, but I was engaged. His friend’s assurance was effected in March. Late in September or early in October I was down at Scarborough for a breath of sea-air, where I met him on the beach. It was a hot evening; he came toward me with his hat in his hand; and there was the walk I had felt so strongly disinclined to take in perfect order again, exactly in front of the bridge of my nose.

So was it Slinkton who was standing next to his bed that time? I mean, the guy is calling at his house. Who else knows where he lives?

So he takes a holiday in Scarborough, well-known seaside destination on the Yorkshire coast. And who should he bump into but MR SLINKTON, slinking about all over the place. That said, I don’t imagine it’s unusual to go on holiday from London and wind up bumping into your London acquaintances. It’s like living in Christchurch, camping at Kaiteri for Christmas, with your tent accidentally pitched right next to your Christchurch neighbours.

But man, this cracker eating bitch is everywhere. I hate the way he walks, the way he stands right in front of my nose like that.

He was not alone, but had a young lady on his arm.

She was dressed in mourning, and I looked at her with great interest. She had the appearance of being extremely delicate, and her face was remarkably pale and melancholy; but she was very pretty. He introduced her as his niece, Miss Niner.

‘Are you strolling, Mr. Sampson? Is it possible you can be idle?’

It was possible, and I was strolling.

‘Shall we stroll together?’

‘With pleasure.’

He’s on a poisoning holiday. Back then, it was very easy to poison someone. Rat poison was almost entirely arsenic, but in a box with a picture of a rat on it. The only trouble was the taste. It tastes terrible, you see, so you had to sneak it into their food in slow, undetectable quantities.

However, this ain’t no arsenic poisoning. In reality, someone with arsenic poisoning will have red, swollen and warty-looking skin. The real life poisoner Thomas Wainewright was thought to have used strychnine. A massive dose of it will end you life with a seizure.

The young lady walked between us, and we walked on the cool sea sand, in the direction of Filey.

‘There have been wheels here,’ said Mr. Slinkton. ‘And now I look again, the wheels of a hand-carriage! Margaret, my love, your shadow without doubt!’

‘Miss Niner’s shadow?’ I repeated, looking down at it on the sand.

‘Not that one,’ Mr. Slinkton returned, laughing. ‘Margaret, my dear, tell Mr. Sampson.’

‘Indeed,’ said the young lady, turning to me, ‘there is nothing to tell—except that I constantly see the same invalid old gentleman at all times, wherever I go. I have mentioned it to my uncle, and he calls the gentleman my shadow.’

‘Does he live in Scarborough?’ I asked.

‘He is staying here.’

‘Do you live in Scarborough?’

Filey used to be a fishing village, but because of its large beach it became popular with tourists.

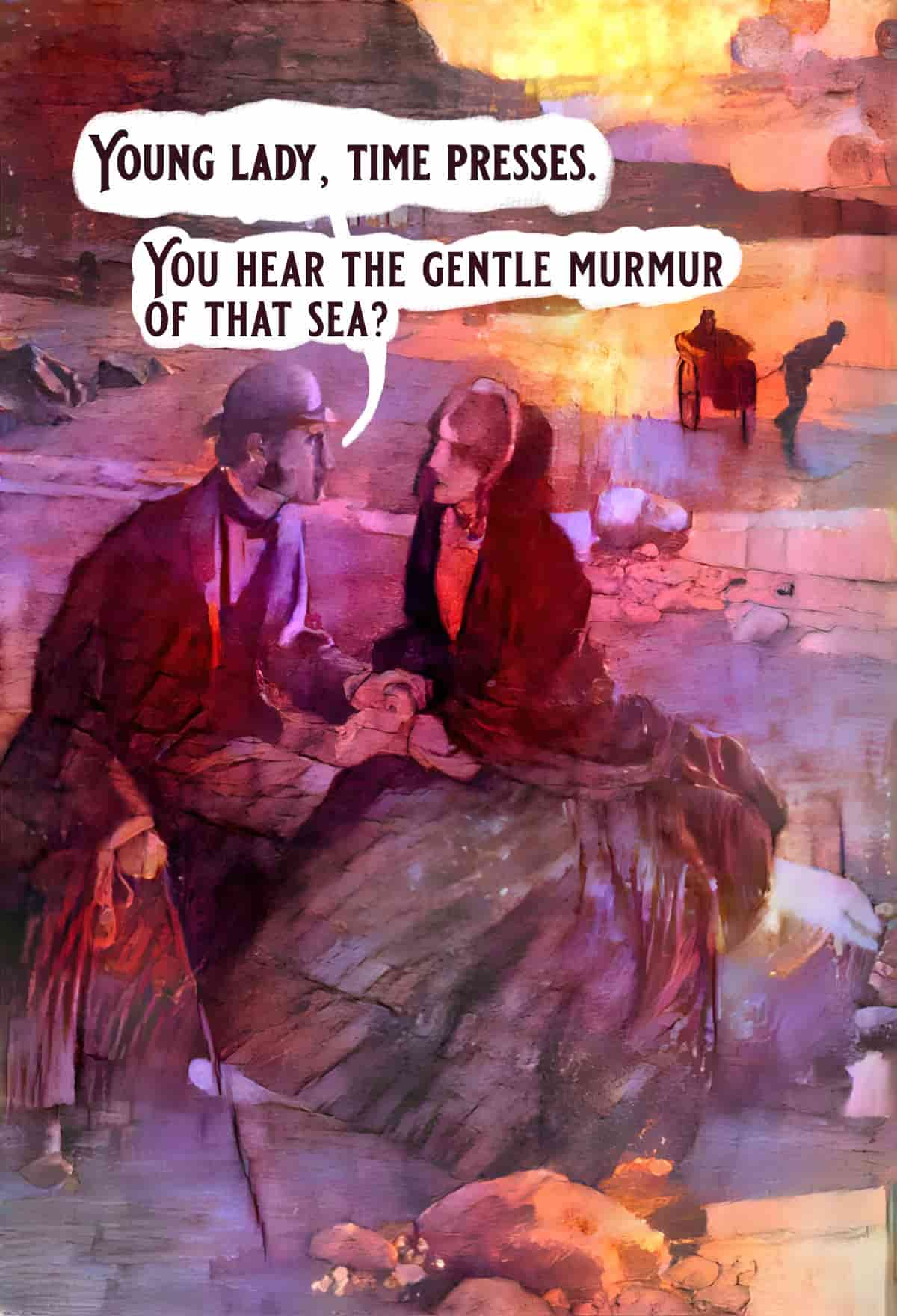

If you’re wondering what a ‘hand carriage’ is, it’s in the background of the illustration below. It’s a small carriage pulled by a person rather than a horse.

Now things get a bit woo-woo. Dickens makes use of a supernatural trope in a non-supernatural, real-world crime story when he talks about this shadow. A shadow can refer to a ghost, but here refers to Mr Meltham (though we don’t yet know it’s Mr Meltham). He’s followed Slinkton and his dead lover’s little sister on holiday so he can keep an eye on Slinkton. He’s clearly not very good at being invisible, or else he wants Slinkton to know he’s being watched.

‘No, I am staying here. My uncle has placed me with a family here, for my health.’

‘And your shadow?’ said I, smiling.

‘My shadow,’ she answered, smiling too, ‘is—like myself—not very robust, I fear; for I lose my shadow sometimes, as my shadow loses me at other times. We both seem liable to confinement to the house. I have not seen my shadow for days and days; but it does oddly happen, occasionally, that wherever I go, for many days together, this gentleman goes. We have come together in the most unfrequented nooks on this shore.’

‘Is this he?’ said I, pointing before us.

The wheels had swept down to the water’s edge, and described a great loop on the sand in turning. Bringing the loop back towards us, and spinning it out as it came, was a hand-carriage, drawn by a man.

‘Yes,’ said Miss Niner, ‘this really is my shadow, uncle.’

The ‘shadow’ has a ghostly quality to it.

As the carriage approached us and we approached the carriage, I saw within it an old man, whose head was sunk on his breast, and who was enveloped in a variety of wrappers. He was drawn by a very quiet but very keen-looking man, with iron-gray hair, who was slightly lame. They had passed us, when the carriage stopped, and the old gentleman within, putting out his arm, called to me by my name. I went back, and was absent from Mr. Slinkton and his niece for about five minutes.

So which of these two men is Mr Meltham? The elderly man being pulled along in the hand carriage, or the slightly lame one with ‘iron-gray hair’ pulling it? Wait, don’t ghosts have a habit of calling you by your name? When our narrator ‘goes back’, does he think he’s encountered a ghost? It seems he’s a little creeped out.

When I rejoined them, Mr. Slinkton was the first to speak. Indeed, he said to me in a raised voice before I came up with him:

‘It is well you have not been longer, or my niece might have died of curiosity to know who her shadow is, Mr. Sampson.’

‘An old East India Director,’ said I. ‘An intimate friend of our friend’s, at whose house I first had the pleasure of meeting you. A certain Major Banks. You have heard of him?’

‘Never.’

‘Very rich, Miss Niner; but very old, and very crippled. An amiable man, sensible—much interested in you. He has just been expatiating on the affection that he has observed to exist between you and your uncle.’

Nope, Mr Sampson the insurance broker narrator knows exactly who ‘the old man’ is.

Oh, I see what he’s up to. He’s in cahoots! As in a heist plot, Dickens has arranged (off-stage) for Sampson and Meltham to get together to hatch a plot to catch Slinkton. When did the pair of them get together to do this? It must have been Mr Meltham who appeared at Sampson’s bedside that morning. He’s posing as a wealthy old man about to die.

Mr. Slinkton was holding his hat again, and he passed his hand up the straight walk, as if he himself went up it serenely, after me.

‘Mr. Sampson,’ he said, tenderly pressing his niece’s arm in his, ‘our affection was always a strong one, for we have had but few near ties. We have still fewer now. We have associations to bring us together, that are not of this world, Margaret.’

‘Dear uncle!’ murmured the young lady, and turned her face aside to hide her tears.

‘My niece and I have such remembrances and regrets in common, Mr. Sampson,’ he feelingly pursued, ‘that it would be strange indeed if the relations between us were cold or indifferent. If I remember a conversation we once had together, you will understand the reference I make. Cheer up, dear Margaret. Don’t droop, don’t droop. My Margaret! I cannot bear to see you droop!’

When this guy takes off his hat to reveal his uncannily straight centre parting, the narrator feels he is revealing his utter badness. The hat itself is a disguise.

I guess when you knock off your entire family, you do end up with ‘few near ties’.

The poor young lady was very much affected, but controlled herself. His feelings, too, were very acute. In a word, he found himself under such great need of a restorative, that he presently went away, to take a bath of sea-water, leaving the young lady and me sitting by a point of rock, and probably presuming—but that you will say was a pardonable indulgence in a luxury—that she would praise him with all her heart.

Modern audiences of crime fiction, largely women, require at least one female character who isn’t an absolute naif, especially since almost every murder story out there also involves the murder of one or multiple pretty young women. That said, I suspect the existence of ‘strong female detectives’ is mistakenly thought to compensate for unnecessary pan shots up and down dead girls’ bodies in mortuaries, and other eroticised forms of visual violence.

She did, poor thing! With all her confiding heart, she praised him to me, for his care of her dead sister, and for his untiring devotion in her last illness. The sister had wasted away very slowly, and wild and terrible fantasies had come over her toward the end, but he had never been impatient with her, or at a loss; had always been gentle, watchful, and self-possessed. The sister had known him, as she had known him, to be the best of men, the kindest of men, and yet a man of such admirable strength of character, as to be a very tower for the support of their weak natures while their poor lives endured.

Worth pointing out: Arsenic toxicity remains a global health problem affecting many millions of people. Contamination from natural geological sources leaches into aquifers, contaminating drinking water. Contamination may also occur from mining and other industrial processes.

‘I shall leave him, Mr. Sampson, very soon,’ said the young lady; ‘I know my life is drawing to an end; and when I am gone, I hope he will marry and be happy. I am sure he has lived single so long, only for my sake, and for my poor, poor sister’s.’

Pretty sure he’s not meant to be interested in women as romantic or sexual partners. Pretty sure Dickens has written Slinkton as on-the-page gay, with his ‘pretty handwriting’ and his pretty clothing in delicate fabrics.

The little hand-carriage had made another great loop on the damp sand, and was coming back again, gradually spinning out a slim figure of eight, half a mile long.

I do wonder if there’s any significance to the number eight, or to the number nine (in the poisoned nieces’ names). Is this how many people Slinkton has poisoned so far? With Miss Niner number nine?

‘Young lady,’ said I, looking around, laying my hand upon her arm, and speaking in a low voice, ‘time presses. You hear the gentle murmur of that sea?’

She looked at me with the utmost wonder and alarm, saying, ‘Yes!’

‘And you know what a voice is in it when the storm comes?’

‘Yes!’

‘You see how quiet and peaceful it lies before us, and you know what an awful sight of power without pity it might be, this very night!’

‘Yes!’

‘But if you had never heard or seen it, or heard of it in its cruelty, could you believe that it beats every inanimate thing in its way to pieces, without mercy, and destroys life without remorse?’

‘You terrify me, sir, by these questions!’

‘To save you, young lady, to save you! For God’s sake, collect your strength and collect your firmness! If you were here alone, and hemmed in by the rising tide on the flow to fifty feet above your head, you could not be in greater danger than the danger you are now to be saved from.’

Instead of telling her straight-up that her uncle murdered her sister and is currently poisoning her to death, too, the narrator chooses instead to speak in heavy metaphor. If he didn’t mean to terrify her, he fails at his task.

The figure on the sand was spun out, and straggled off into a crooked little jerk that ended at the cliff very near us.

Note the word ‘crooked’. This story is full of crookedness and straightness.

‘As I am, before Heaven and the Judge of all mankind, your friend, and your dead sister’s friend, I solemnly entreat you, Miss Niner, without one moment’s loss of time, to come to this gentleman with me!’

He thinks a lot of himself, doesn’t he?

If the little carriage had been less near to us, I doubt if I could have got her away; but it was so near that we were there before she had recovered the hurry of being urged from the rock. I did not remain there with her two minutes. Certainly within five, I had the inexpressible satisfaction of seeing her—from the point we had sat on, and to which I had returned—half supported and half carried up some rude steps notched in the cliff, by the figure of an active man. With that figure beside her, I knew she was safe anywhere.

If this story had been written by a woman, and not by a privileged white man who didn’t go out on the streets of London with the Victorian equivalent of car keys daggered between his fingers as self-protection, she might have written this differently. For a young, sick woman to be whisked away by two men, away from the uncle you (mistakenly) trust, is truly traumatising. Instead, the narrator finds his success in saving Miss Niner ‘satisfying’. He doesn’t see it from her perspective at all. For storytelling purposes, Miss Niner is a one-dimensional ‘perfect victim’.

I sat alone on the rock, awaiting Mr. Slinkton’s return. The twilight was deepening and the shadows were heavy, when he came round the point, with his hat hanging at his button-hole, smoothing his wet hair with one of his hands, and picking out the old path with the other and a pocket-comb.

‘My niece not here, Mr. Sampson?’ he said, looking about.

‘Miss Niner seemed to feel a chill in the air after the sun was down, and has gone home.’

Worse, they’ve kidnapped her just as darkness is setting in. For storytelling purposes, this is metaphorical: The end of a day, the end of a life, yadda yadda.

He looked surprised, as though she were not accustomed to do anything without him; even to originate so slight a proceeding.

‘I persuaded Miss Niner,’ I explained.

‘Ah!’ said he. ‘She is easily persuaded—for her good. Thank you, Mr. Sampson; she is better within doors. The bathing-place was farther than I thought, to say the truth.’

‘Miss Niner is very delicate,’ I observed.

‘Not accustomed to doing anything without him.’ Fortunately, the term ‘coercive control’ is starting to become better known and more widely understood with the huge efforts of a few activists working in sphere of intimate partner violence. But writers have been describing coercive controllers for decades. Forever.

He shook his head and drew a deep sigh. ‘Very, very, very. You may recollect my saying so. The time that has since intervened has not strengthened her. The gloomy shadow that fell upon her sister so early in life seems, in my anxious eyes, to gather over her, ever darker, ever darker. Dear Margaret, dear Margaret! But we must hope.’

The hand-carriage was spinning away before us at a most indecorous pace for an invalid vehicle, and was making most irregular curves upon the sand. Mr. Slinkton, noticing it after he had put his handkerchief to his eyes, said:

‘If I may judge from appearances, your friend will be upset, Mr. Sampson.’

‘It looks probable, certainly,’ said I.

‘The servant must be drunk.’

‘The servants of old gentlemen will get drunk sometimes,’ said I.

‘The major draws very light, Mr. Sampson.’

‘The major does draw light,’ said I.

This is where the story turns to slapstick, with a hand carriage supposedly containing a very sick man doing wheelies on the sand. Comically, the con man has no idea what’s happening and observes, “The major draws very light”, meaning there’s not much heft to him.

By this time the carriage, much to my relief, was lost in the darkness. We walked on for a little, side by side over the sand, in silence. After a short while he said, in a voice still affected by the emotion that his niece’s state of health had awakened in him,

‘Do you stay here long, Mr. Sampson?’

‘Why, no. I am going away to-night.’

‘So soon? But business always holds you in request. Men like Mr. Sampson are too important to others, to be spared to their own need of relaxation and enjoyment.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ said I. ‘However, I am going back.’

‘To London?’

‘To London.’

‘I shall be there too, soon after you.’

This passage ends on what might be interpreted as a threat.

I knew that as well as he did. But I did not tell him so. Any more than I told him what defensive weapon my right hand rested on in my pocket, as I walked by his side. Any more than I told him why I did not walk on the sea side of him with the night closing in.

Mr Sampson and Meltham are one step ahead of the con man now. The good thing about catching con men: They think they’re smarter than everyone else, which leads them to underestimate their opponents. (They’re full of their own confidence. Con is an abbreviation of confidence.) This is their weakness and they are easily caught.

We left the beach, and our ways diverged. We exchanged good-night, and had parted indeed, when he said, returning,

‘Mr. Sampson, may I ask? Poor Meltham, whom we spoke of,—dead yet?’

‘Not when I last heard of him; but too broken a man to live long, and hopelessly lost to his old calling.’

‘Dear, dear, dear!’ said he, with great feeling. ‘Sad, sad, sad! The world is a grave!’ And so went his way.

“Is he dead yet?” Very delicate phrasing. Haha

It was not his fault if the world were not a grave; but I did not call that observation after him, any more than I had mentioned those other things just now enumerated. He went his way, and I went mine with all expedition. This happened, as I have said, either at the end of September or beginning of October. The next time I saw him, and the last time, was late in November.

The pair will next meet when the weather is much colder.

CHAPTER FIVE

I had a very particular engagement to breakfast in the Temple. It was a bitter north-easterly morning, and the sleet and slush lay inches deep in the streets. I could get no conveyance, and was soon wet to the knees; but I should have been true to that appointment, though I had to wade to it up to my neck in the same impediments.

Dickens is juxtaposing the seasons. He’s taken us from a summer holiday at the seaside to bitter cold sleet.

The appointment took me to some chambers in the Temple. They were at the top of a lonely corner house overlooking the river. The name, Mr. Alfred Beckwith, was painted on the outer door. On the door opposite, on the same landing, the name Mr. Julius Slinkton. The doors of both sets of chambers stood open, so that anything said aloud in one set could be heard in the other.

The narrator approaches the evil lair. Remember, Alfred Beckwith is an alias of Mr Meltham. He’s moved in opposite the poisoner to gain proximity, crack on he’s ill, and to trick Slinkton into underestimating him.

I had never been in those chambers before. They were dismal, close, unwholesome, and oppressive; the furniture, originally good, and not yet old, was faded and dirty,—the rooms were in great disorder; there was a strong prevailing smell of opium, brandy, and tobacco; the grate and fire-irons were splashed all over with unsightly blotches of rust; and on a sofa by the fire, in the room where breakfast had been prepared, lay the host, Mr. Beckwith, a man with all the appearances of the worst kind of drunkard, very far advanced upon his shameful way to death.

Storytellers encourage audiences to judge a character by the house in which they live. Given the extent to which housing is dependent on fortune, I sometimes wonder if this is basically another contemporary version of phrenology and physiognomy.

The disgusting state of Slinkton’s house is supposed to reveal the disgusting state of Slinkton’s inner self. We see this all the time in modern storytelling — house as self — yet the most disgusting people in the real world live in towers with golden toilets.

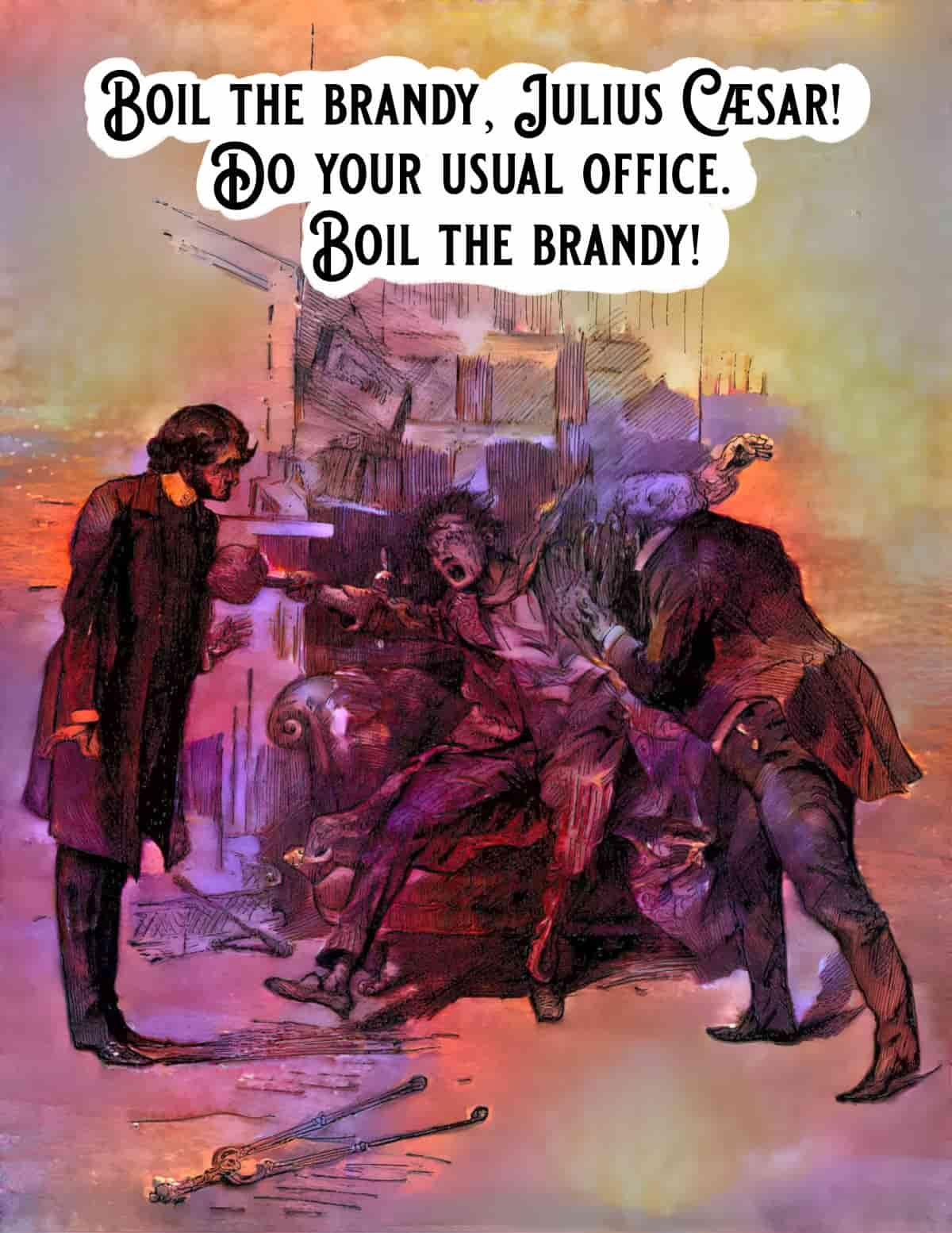

‘Slinkton is not come yet,’ said this creature, staggering up when I went in; ‘I’ll call him.—Halloa! Julius Cæsar! Come and drink!’ As he hoarsely roared this out, he beat the poker and tongs together in a mad way, as if that were his usual manner of summoning his associate.

This is Meltham pretending to be drunk, and because he’s an actuary, not an actor, he’s really hamming it up. This is a slapstick sequence.

The voice of Mr. Slinkton was heard through the clatter from the opposite side of the staircase, and he came in. He had not expected the pleasure of meeting me. I have seen several artful men brought to a stand, but I never saw a man so aghast as he was when his eyes rested on mine.

‘Julius Cæsar,’ cried Beckwith, staggering between us, ‘Mist’ Sampson! Mist’ Sampson, Julius Cæsar! Julius, Mist’ Sampson, is the friend of my soul. Julius keeps me plied with liquor, morning, noon, and night. Julius is a real benefactor. Julius threw the tea and coffee out of window when I used to have any. Julius empties all the water-jugs of their contents, and fills ’em with spirits. Julius winds me up and keeps me going.—Boil the brandy, Julius!’

Meltham calls Julius Slinkton Julius Cæsar as a nickname, but also because Cæsar was an important man, and this comparison is exactly the sort of thing Slinkton would like, reminding him he’s all powerful, very important, an historical figure.

We learn in this paragraph that Slinkton is poisoning this neighbour with liquor. He’s buying it in for him, and also replaces any other beverages with alcohol. That said, boiling brandy would get the alcohol out of it. In Serbia, boiled brandy is akin to mulled wine.

There was a rusty and furred saucepan in the ashes,—the ashes looked like the accumulation of weeks,—and Beckwith, rolling and staggering between us as if he were going to plunge headlong into the fire, got the saucepan out, and tried to force it into Slinkton’s hand.

‘Boil the brandy, Julius Cæsar! Come! Do your usual office. Boil the brandy!’

He became so fierce in his gesticulations with the saucepan, that I expected to see him lay open Slinkton’s head with it. I therefore put out my hand to check him. He reeled back to the sofa, and sat there panting, shaking, and red-eyed, in his rags of dressing-gown, looking at us both. I noticed then that there was nothing to drink on the table but brandy, and nothing to eat but salted herrings, and a hot, sickly, highly-peppered stew.

Slinkton has been feeding Meltham’s character a diet heavy in salt and pepper hoping to create more thirst.

‘At all events, Mr. Sampson,’ said Slinkton, offering me the smooth gravel path for the last time, ‘I thank you for interfering between me and this unfortunate man’s violence. However you came here, Mr. Sampson, or with whatever motive you came here, at least I thank you for that.’

‘Boil the brandy,’ muttered Beckwith.

Without gratifying his desire to know how I came there, I said, quietly, ‘How is your niece, Mr. Slinkton?’

He looked hard at me, and I looked hard at him.

‘Smooth gravel’ is an oxymoron, like the straight hair parting on a crooked man.

‘I am sorry to say, Mr. Sampson, that my niece has proved treacherous and ungrateful to her best friend. She left me without a word of notice or explanation. She was misled, no doubt, by some designing rascal. Perhaps you may have heard of it.’

‘I did hear that she was misled by a designing rascal. In fact, I have proof of it.’

‘Are you sure of that?’ said he.

‘Quite.’

‘Boil the brandy,’ muttered Beckwith. ‘Company to breakfast, Julius Cæsar. Do your usual office,—provide the usual breakfast, dinner, tea, and supper. Boil the brandy!’

The eyes of Slinkton looked from him to me, and he said, after a moment’s consideration,

‘Mr. Sampson, you are a man of the world, and so am I. I will be plain with you.’

‘O no, you won’t,’ said I, shaking my head.

‘I tell you, sir, I will be plain with you.’

‘And I tell you you will not,’ said I. ‘I know all about you. You plain with any one? Nonsense, nonsense!’

Hero and opponent suss each other out. Does the other know what has happened?

‘I plainly tell you, Mr. Sampson,’ he went on, with a manner almost composed, ‘that I understand your object. You want to save your funds, and escape from your liabilities; these are old tricks of trade with you Office-gentlemen. But you will not do it, sir; you will not succeed. You have not an easy adversary to play against, when you play against me. We shall have to inquire, in due time, when and how Mr. Beckwith fell into his present habits. With that remark, sir, I put this poor creature, and his incoherent wanderings of speech, aside, and wish you a good morning and a better case next time.’

Now that Slinkton has been found out, his only recourse is a threat. Like Walter White with Hank in the garage in the famous ‘Tread Lightly’ scene. Don’t mess with me. I’m more powerful than you are.

While he was saying this, Beckwith had filled a half-pint glass with brandy. At this moment, he threw the brandy at his face, and threw the glass after it. Slinkton put his hands up, half blinded with the spirit, and cut with the glass across the forehead. At the sound of the breakage, a fourth person came into the room, closed the door, and stood at it; he was a very quiet but very keen-looking man, with iron-gray hair, and slightly lame.

The tension is broken with this over-the-top slapstick scene, played by a man pretending to be drunk.

Finally we get to meet the guy with the iron-gray hair, who was pulling the hand carriage on the beach.

Slinkton pulled out his handkerchief, assuaged the pain in his smarting eyes, and dabbled the blood on his forehead. He was a long time about it, and I saw that in the doing of it, a tremendous change came over him, occasioned by the change in Beckwith,—who ceased to pant and tremble, sat upright, and never took his eyes off him. I never in my life saw a face in which abhorrence and determination were so forcibly painted as in Beckwith’s then.

‘A tremendous change came over him’, like a supernatural transmogrification. This monsterfies him, reminiscent of Jekyll and Hyde or The Incredible Hulk.

‘Look at me, you villain,’ said Beckwith, ‘and see me as I really am. I took these rooms, to make them a trap for you. I came into them as a drunkard, to bait the trap for you. You fell into the trap, and you will never leave it alive. On the morning when you last went to Mr. Sampson’s office, I had seen him first. Your plot has been known to both of us, all along, and you have been counter-plotted all along. What? Having been cajoled into putting that prize of two thousand pounds in your power, I was to be done to death with brandy, and, brandy not proving quick enough, with something quicker? Have I never seen you, when you thought my senses gone, pouring from your little bottle into my glass? Why, you Murderer and Forger, alone here with you in the dead of night, as I have so often been, I have had my hand upon the trigger of a pistol, twenty times, to blow your brains out!’

Now, in case readers haven’t picked up every last detail, Dickens gives us a summary of what just happened. Unlike you and me, who probably read this story in a single sitting, readers of the mid 1800s had to wait between each instalment and probably forgot what came before.

A note about spiking: We have been taught to associate drink spiking with drugs, but the most common, troublingly workaday form of spiking is to ply someone with more alcohol than they know they’re getting, for example by giving them the drink they ordered but with an extra shot in it.

This sudden starting up of the thing that he had supposed to be his imbecile victim into a determined man, with a settled resolution to hunt him down and be the death of him, mercilessly expressed from head to foot, was, in the first shock, too much for him. Without any figure of speech, he staggered under it. But there is no greater mistake than to suppose that a man who is a calculating criminal, is, in any phase of his guilt, otherwise than true to himself, and perfectly consistent with his whole character. Such a man commits murder, and murder is the natural culmination of his course; such a man has to outface murder, and will do it with hardihood and effrontery. It is a sort of fashion to express surprise that any notorious criminal, having such crime upon his conscience, can so brave it out. Do you think that if he had it on his conscience at all, or had a conscience to have it upon, he would ever have committed the crime?

Dickens gives us some philosophy on the nature of evil men. This idea that some people are simply born bad, and that every single thing they do are bad, is intimately connected to physiognomy. You can’t trust in physiognomy as a measure of character unless you also believe that people are just born that way (as in bad).

Perfectly consistent with himself, as I believe all such monsters to be, this Slinkton recovered himself, and showed a defiance that was sufficiently cold and quiet. He was white, he was haggard, he was changed; but only as a sharper who had played for a great stake and had been outwitted and had lost the game.

Dickens has already shown Slinkton as a monster, now he uses the word. Some men are just monsters, we learn via storytelling, and there’s nothing we can do with them except protect the public from further harm. These ideas continue to influence the carceral system to this day.

‘Listen to me, you villain,’ said Beckwith, ‘and let every word you hear me say be a stab in your wicked heart. When I took these rooms, to throw myself in your way and lead you on to the scheme that I knew my appearance and supposed character and habits would suggest to such a devil, how did I know that? Because you were no stranger to me. I knew you well. And I knew you to be the cruel wretch who, for so much money, had killed one innocent girl while she trusted him implicitly, and who was by inches killing another.’

I’m really not sure why Slinkton doesn’t at least try to make an escape. That’d be in his nature. (It’s all there in the name.) Maybe the three other men would overpower him.

Slinkton took out a snuff-box, took a pinch of snuff, and laughed.

Baddies often laugh while they’re doing something routine, like snuff, or eating a sandwich. They seem more evil that way.

‘But see here,’ said Beckwith, never looking away, never raising his voice, never relaxing his face, never unclenching his hand. ‘See what a dull wolf you have been, after all! The infatuated drunkard who never drank a fiftieth part of the liquor you plied him with, but poured it away, here, there, everywhere—almost before your eyes; who bought over the fellow you set to watch him and to ply him, by outbidding you in his bribe, before he had been at his work three days—with whom you have observed no caution, yet who was so bent on ridding the earth of you as a wild beast, that he would have defeated you if you had been ever so prudent—that drunkard whom you have, many a time, left on the floor of this room, and who has even let you go out of it, alive and undeceived, when you have turned him over with your foot—has, almost as often, on the same night, within an hour, within a few minutes, watched you awake, had his hand at your pillow when you were asleep, turned over your papers, taken samples from your bottles and packets of powder, changed their contents, rifled every secret of your life!’

Now Dickens gives us the backstory of precisely how Meltham foiled Slinkton. I don’t think I needed this backstory. Then again, Dickens was paid by the word (and handsomely).

He had had another pinch of snuff in his hand, but had gradually let it drop from between his fingers to the floor; where he now smoothed it out with his foot, looking down at it the while.

His plans to ‘snuff’ Beckwith have gone.

‘That drunkard,’ said Beckwith, ‘who had free access to your rooms at all times, that he might drink the strong drinks that you left in his way and be the sooner ended, holding no more terms with you than he would hold with a tiger, has had his master-key for all your locks, his test for all your poisons, his clue to your cipher-writing. He can tell you, as well as you can tell him, how long it took to complete that deed, what doses there were, what intervals, what signs of gradual decay upon mind and body; what distempered fancies were produced, what observable changes, what physical pain. He can tell you, as well as you can tell him, that all this was recorded day by day, as a lesson of experience for future service. He can tell you, better than you can tell him, where that journal is at this moment.’

Slinkton stopped the action of his foot, and looked at Beckwith.

‘No,’ said the latter, as if answering a question from him. ‘Not in the drawer of the writing-desk that opens with a spring; it is not there, and it never will be there again.’

‘Then you are a thief!’ said Slinkton.

Without any change whatever in the inflexible purpose, which it was quite terrific even to me to contemplate, and from the power of which I had always felt convinced it was impossible for this wretch to escape, Beckwith returned,

‘And I am your niece’s shadow, too.’

It’s great when mass murderers keep a journal detailing every aspect of their crimes. It will presumably be used as evidence.

With an imprecation Slinkton put his hand to his head, tore out some hair, and flung it to the ground. It was the end of the smooth walk; he destroyed it in the action, and it will soon be seen that his use for it was past.

Imprecation: a spoken curse. The mask is off; his perfect hair-line is now mussed up, a true reflection of the rascal that he is.

Beckwith went on: ‘Whenever you left here, I left here. Although I understood that you found it necessary to pause in the completion of that purpose, to avert suspicion, still I watched you close, with the poor confiding girl. When I had the diary, and could read it word by word,—it was only about the night before your last visit to Scarborough,—you remember the night? you slept with a small flat vial tied to your wrist,—I sent to Mr. Sampson, who was kept out of view. This is Mr. Sampson’s trusty servant standing by the door. We three saved your niece among us.’

We finally learn who the grey haired man is. Mr Sampson’s trusty servant. I’ve been wondering for ages. Not sure how I didn’t work it out. Guess I was thinking of Edward Cullen.

Slinkton looked at us all, took an uncertain step or two from the place where he had stood, returned to it, and glanced about him in a very curious way,—as one of the meaner reptiles might, looking for a hole to hide in. I noticed at the same time, that a singular change took place in the figure of the man,—as if it collapsed within his clothes, and they consequently became ill-shapen and ill-fitting.

Aha. All along, Dickens has been painting Slinkton as one of the ‘meaner reptiles’. A slinking lizard. So many storytellers compare characters to animals, for ages I made up my own word (animalification) but turns out there’s an actual existing word to describe this literary technique.

‘You shall know,’ said Beckwith, ‘for I hope the knowledge will be bitter and terrible to you, why you have been pursued by one man, and why, when the whole interest that Mr. Sampson represents would have expended any money in hunting you down, you have been tracked to death at a single individual’s charge. I hear you have had the name of Meltham on your lips sometimes?’

I saw, in addition to those other changes, a sudden stoppage come upon his breathing.

‘When you sent the sweet girl whom you murdered (you know with what artfully made-out surroundings and probabilities you sent her) to Meltham’s office, before taking her abroad to originate the transaction that doomed her to the grave, it fell to Meltham’s lot to see her and to speak with her. It did not fall to his lot to save her, though I know he would freely give his own life to have done it. He admired her;—I would say he loved her deeply, if I thought it possible that you could understand the word. When she was sacrificed, he was thoroughly assured of your guilt. Having lost her, he had but one object left in life, and that was to avenge her and destroy you.’

Remember, the reader doesn’t yet know that Meltham is playing Beckwith.

I saw the villain’s nostrils rise and fall convulsively; but I saw no moving at his mouth.

‘That man Meltham,’ Beckwith steadily pursued, ‘was as absolutely certain that you could never elude him in this world, if he devoted himself to your destruction with his utmost fidelity and earnestness, and if he divided the sacred duty with no other duty in life, as he was certain that in achieving it he would be a poor instrument in the hands of Providence, and would do well before Heaven in striking you out from among living men. I am that man, and I thank God that I have done my work!’

In case you think this story should’ve wrapped up by about now, here’s the main revelation. The identity of the dupe. In a transgression story like this, the con artist cannot remain masked, and nor can the dupe.

If Slinkton had been running for his life from swift-footed savages, a dozen miles, he could not have shown more emphatic signs of being oppressed at heart and labouring for breath, than he showed now, when he looked at the pursuer who had so relentlessly hunted him down.

A bit of racism thrown in, to remind us of the times

‘You never saw me under my right name before; you see me under my right name now. You shall see me once again in the body, when you are tried for your life. You shall see me once again in the spirit, when the cord is round your neck, and the crowd are crying against you!’

When Meltham had spoken these last words, the miscreant suddenly turned away his face, and seemed to strike his mouth with his open hand. At the same instant, the room was filled with a new and powerful odour, and, almost at the same instant, he broke into a crooked run, leap, start,—I have no name for the spasm,—and fell, with a dull weight that shook the heavy old doors and windows in their frames.

He hits his own face and then… farts? Uh, he drops dead. Okay, so he’s poisoned himself with strychnine, which he carries around with him at all times. Apparently strychnine is odourless (though I’ve never had the chance to sniff it myself). Is the odour something Dickens invented for the story?

That was the fitting end of him.

When we saw that he was dead, we drew away from the room, and Meltham, giving me his hand, said, with a weary air,

‘I have no more work on earth, my friend. But I shall see her again elsewhere.’

Er, ‘fitting’? Is this a mean-ass pun?

It was in vain that I tried to rally him. He might have saved her, he said; he had not saved her, and he reproached himself; he had lost her, and he was broken-hearted.

‘The purpose that sustained me is over, Sampson, and there is nothing now to hold me to life. I am not fit for life; I am weak and spiritless; I have no hope and no object; my day is done.’

In truth, I could hardly have believed that the broken man who then spoke to me was the man who had so strongly and so differently impressed me when his purpose was before him. I used such entreaties with him, as I could; but he still said, and always said, in a patient, undemonstrative way,—nothing could avail him,—he was broken-hearted.