SpongeBob Squarepants is a fast-paced children’s cartoon for a dual audience, written by a guy who is also a marine biologist. This is a highly successful and long-running show, with humour that broadly appeals.

This series has been running since 1999. Critics say the show has been declining in quality in the last few years, which is what critics also say of The Simpsons. What is the longest time a comedy series should run for? Are there any examples of comedy series lasting longer than a decade without a serious decline in quality? I can’t think of any myself.

[Update: Sadly, Stephen Hillenburg died September 2018.]

Here I use Scott Dikkers’ 11 Categories Of Jokes to focus on the humour of SpongeBob. I’ve used so many SpongeBob examples in that original post that I’m ready to do an entire SpongeBob post. (If you feel that analysing jokes takes the joy out of comedy, this post is not for you!) Studying humour is a lot like doing tennis drills. Concentrate on form and process during deliberate training sessions, but once you’re playing a game (actually writing comedy) we need to put everything you know aside and get into a state of flow.

It’s also worth looking at other people’s comedy writing to hone your own sense of what’s funny and what’s not. While I find most of SpongeBob’s humour funny, I get annoyed with some of it, too. (Backed up by Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid sales as evidence, sexism sells.)

First a note about the structure.

THE PLOT STRUCTURE OF SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS

A lot of the SpongeBob Squarepants episodes follow a very common plot structure for fast paced comedies of about 11 minutes long. (This is also about the length of a We Bare Bears episode — equally fast paced with a heavy joke density and surprisingly complex plots.)

The double thread plot is popular with SpongeBob writers.

- The plot will begin either with SpongeBob or with his opponent.

- SpongeBob gets into trouble.

- The opponent also faces challenges.

- These two threads come together during the Battle sequence, and the audience learns how the two separate threads are inextricably linked. One thread doesn’t fly without the other.

Seinfeld also uses this structure a lot.

OPPONENTS

The characters who live in Bikini Bottom have their own web of opposition which provides the most layered and interesting conflict of each episode. However, there is usually a big, bad baddie who comes into town. In episode one it’s a hoard of hungry anchovies. In Bubblestand it’s a massive bubble which envelops Squidward’s house and carries him away, suddenly uniting the SpongeBob/Patrick team with Squidward — they (briefly) feel sorry for him.

Related: New Genetic Study Reveals Sea Stars Are Just A Bunch of Heads Smushed Together: How this iconic animal got its shape has been an ongoing mystery for biologists.

SpongeBob’s gang is made up of his best friend Patrick, who is the stupider but kinder version of SpongeBob, much like the Greg Heffley and Rowley friendship in Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Then there’s Squidward making up the threesome, who is sort of part of their gang but not actually because he doesn’t find SpongeBob and Patrick funny. Squidward embodies the seven deadly sins and then some — depending on the episode, Squidward is everything we despise in people. He is haughty, has no sense of fun, sarcastic, selfish and so on.

The threesome/twosome friendship plus an oddball outsider is pretty common in comedy.

In Seinfeld we have Jerry, George and Elaine, plus the unfathomable quirk of Kramer across the hall.

As mentioned above, there’s the Wimpy Kid stars and then there’s Fregley, who would like to be one of the gang but is just too odd for even Greg and Rowley, who get up to plenty of odd stuff in their own right. That’s the raison d’etre of these super odd character of course — Fregley’s weirdness actually provides verisimilitude to whatever those other two get up to. It doesn’t matter how weird Greg’s life is, it’s never as weird as Fregley’s.

Although these characters spend a lot of time conflicting with each other, they do band together when a bigger, badder outsider comes along. This creates a double layer of opposition:

- Opposition within the in-group

- Opposition between the in-group and the outsider (the big, bad baddie who comes into town)

Pilot Episode

SpongeBob wants a job at the Krusty Krab as a cook. He is sent out on an impossible mission to find a super powerful spatula (which he ironically finds easily at the supermarket).

Meanwhile, back at the Krusty Krab, a whole lot of hungry anchovies turn up and create havoc for the restaurant owner and Squidward. (The anchovies are the big, bad outsiders.)

These two plot threads come together as soon as SpongeBob arrives back at the Krusty Krab with his super-powerful spatula, which just so happens to be exactly the unlikely implement needed to knock out meals at a super quick rate, feeding all the hungry anchovies and saving the day.

Bubblestand

This is a quiet story, which is in line with the mesmerising activity of bubble blowing. SpongeBob sets up a bubble stand (like a lemonade stand) right outside Squidward’s house.

Inside his own home, Squidward tries to practise his clarinet, but the bubbles outside are creating an unlikely amount of trouble for him.

The threads come together when a bigger, badder opponent comes into town, suddenly putting these neighbours on the same side. (A massive bubble which carries Squidward away.)

Ripped Pants

This episode does not have the dual plot line going on. It is a simple parable with a clear message for its viewers: If you keep recycling a joke it stops being funny and starts irritating people. You will alienate your friends. This episode therefore has the single strand plot line, like a parable. The New Situation phase is actually a song, explaining the lesson in the way those old parables and Charles Perrault fairytales used to do in a paragraph.

Walking Small

This episode opens with the point-of-view of the opponent — the tiny Plankton, who wants SpongeBob to help him clean up the beach, as he himself is too small to make a difference. Plankton is not a formidable villain, but is still an opponent, because SpongeBob does not want to spend his days cleaning up the beach. SpongeBob’s goals are simply to have fun. Plankton is a fake ally opponent, instructing SpongeBob to be formidable, though SpongeBob obviously doesn’t have it in him, being nice when he’s meant to be assertive. SpongeBob eventually realises what the deal is and decides that if he can’t be aggressively mean, he can be aggressively nice. The entire story takes place on ‘the beach’, which is funny because there can’t be a ‘beach’ at the bottom of the ocean. The outtake shows him enjoying a game of volleyball, and the lesson is that it’s more fun to be nice than to be maniacal.

Notice that the ‘lessons’ in SpongeBob episodes are very obvious ones, and therefore very knowing. Though the youngest viewers might take these lessons to heart, older viewers know that these lessons exist only because SpongeBob is a parody of didacticism itself.

HUMOUR IN SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS

Even the music goes a long way towards setting a comical scene, with a tune by Tiny Tim in the pilot, and an outtake tune which sounds like slightly off-beat banjos. (Country music is easy to make fun of, just as it’s easy to make fun of country hicks.)

1. IRONY

The entire series is ironic on every level. But let’s break it down just a little.

Irony is a ‘meaningful gap between expectation and outcome’.

In that pilot episode, we don’t expect SpongeBob to arrive back with a super powerful spatula, which we have been told doesn’t even exist. On a story level, we didn’t expect SpongeBob to secure his job at the Krusty Krab by saving his new boss from marauding hungry anchovies.

Irony might simply be the opposite reaction from the one expected. For instance, when selling door-to-door, Patrick’s eyeballs pop out of his head like worms and he gets them slammed in the door. Instead of saying “ouch” (the expected reaction) the eyeballs look around and Patrick says, from the other side of the door, “ nice place you got here!” This joke has several funny filters, the other one being he is so stupid he can’t feel pain.

2. CHARACTER HUMOUR

This is where it’s very easy to get mean about certain groups of people. But it’s also where a lot of excellent humour comes from.

GENDER, AGE AND POWER

Much humour derives from power flowing away a character, especially if that character generally has a powerful position in society. Mermaid Man, for instance is a parody on the superhero trope. Mermaid Man has no power at all really because:

- He lives in an old people’s home

- He dresses as a girl

Ageism is a slightly separate issue — we’re all going to get old at some point (if we’re lucky). Sexism, on the other hand, will never affect hetero cis boys in quite the same way so it’s worth taking a much closer look at that.

While Barnacle Boy is neutral and therefore unproblematic, the fact that his sidekick Mermaid Man wears the bikini of shells means that Mermaid Man is doubly disempowered: age and gender expression are against him. At first glance this may seem innocent humour, except that the joke doesn’t work if genders are reversed.

MEANNESS EXERCISE FOR COMEDY WRITERS: This is always a good yardstick to measure by. Does the joke still work if you reverse the genders? If not, it will stand out as horribly dated in a few decades’ time, and as horrible right now to many of your contemporary audience as well.

SpongeBob Squarepants the series gets a lot of mileage out of sexist jokes, which is what inevitably happens when the entire writing team is men — they inevitably write for a male audience.

Why is the town called Bikini Bottom? Because for boys there seems to be some discomfort around female clothing. And anything that causes mild discomfort is ripe for turning into comedy. Pants in general are also generally funny in children’s comedy, but if those pants are related to sexuality, now you’ve got a joke that spans two opportunities for discomfort: bum jokes AND sexual humour, otherwise known as ‘adolescent humour’.

Sandy Cheeks the squirrel is the female sexual opponent, meaning SpongeBob is sexually interested in this character, tries to impress her, and much of the humour derives from him failing as a man. This pokes fun at masculinity, at the same time as reinforcing it. No one is meant to learn from SpongeBob how to be a man, just as no one really takes the didacticism of SpongeBob straight. But this line of jokes remains problematic, not because of its explicit message, but because of the tacit ones. Anyone working in advertising will tell you, tacit messages are the more powerful.

We first meet Sandy in Tea At The Tree Dome. Sandy invites SpongeBob back to her dome where there is no water (because she is a squirrel). SpongeBob has told Sandy that he, too, likes water-free places. This is a joke aimed at the older portion of the audience — an example ‘reference humour’ based on the common phenomenon of trying to make out you like the same things as a sexual target even though you really don’t. It is always revealed over the course of a relationship that you really don’t like the things you pretended to like, which is a great example of transgression comedy, in which the ‘mask’ comes off and we laugh because it is both deserved and uncomfortable, and the reactions of the characters delight.

We next meet Sandy Cheeks at the beach, where Sandy continues to innocently think she and SpongeBob are just friends. She laughs wholeheartedly at SpongeBob’s jokes and SpongeBob thinks he’s well and truly on his way to persuading Sandy that he would make good boyfriend material. But then a big, strong manly crab turns up and Sandy decides to go with him to lift weights. SpongeBob is thoroughly humiliated when it turns out even Sandy can lift heavier weights than he can. Comedy comes from SpongeBob’s extreme shortcoming — even a stick with marshmallows on the ends sends him sinking into the sand. Viewers of all genders are familiar with the male tendency to show off for sexual gain. Everybody gets the reference humour of this dynamic. But it’s only one end of the gender spectrum who sees themselves time and again as the unwitting object of the desire in comedy. Spoiler alert: the femme coded genders.

This seems utterly innocent, until you take a look at SpongeBob’s utter persistence. He believes that so long as he persists, Sandy will eventually become his girlfriend. She’s simply too stupid to realise what he’s trying to achieve. In this super common (bog standard) comedy plot line, the ideology of persistence has a real and damaging effect on how boys are taught to see girls. The audience is taught to empathise heavily with the ‘loss’ of romance (though it was never achieved to begin with). That means we empathise with SpongeBob, but at no point empathise with Sandy. At the extreme real life version of this narrative, we get a boy shooting an ex-girlfriend in school, and the police describe the boy as ‘lovesick’. That’s because we are all taught time and again, from drama to comedy, to empathise with the plight of romantic failure, and not taught to empathise with the object’s wish to be friends, or to be left well alone.

Weirdly, we learn later in the Ripped Pants episode that SpongeBob has ‘lost his best friend’ (owing to bad jokes about ripped pants). Yet he interacts with this ‘friend’ like she’s a sexual target. This is why I don’t buy arguments that SpongeBob Squarepants the show can’t be a sexist show because SpongeBob the character is asexual.

Some of the episodes with Sandy Cheeks are downright weird. In the Texas episode, Sandy is sad. SpongeBob is the last to understand why (long after the viewers), hanging off that trope that men can’t understand women and women’s feelings. Eventually Sandy sings a heartfelt ballad about how much she misses Texas and SpongeBob finally understands her sadness. Sandy gets on a bus to leave Bikini Bottom forever, but SpongeBob and Patrick realise (by accident) that if they insult Texas she will hang around to defend her home state. Earlier, they stand by her bed and watch her sleep. Which, fine, but take all these behaviours together and the entire episode comprises creepy boundary crossing and negging. (Stephenie Meyer catches a lot of crap for the exact same storyline — a male character goes into a female character’s bedroom and watches her sleep.) Because of the (mock) didactic story structure of this series, Sandy learns at the end that home is where there are people who care about you. (Caring = insulting the things you love.)

Mrs Puff, because of her female gender, also becomes a romantic target even though she is initially presented as a middle-aged motherly teacher type. She becomes the romantic object for the older Mr Krabbe, who is so enamoured by her he bankrupts himself buying her gifts. Although the male characters are always presented as inept and slightly crazy for the lengths they will go to for love, the fact remains — if a female character appears in SpongeBob, she is eventually utilised as a romantic target. A female character’s sexuality is therefore her main characteristic.

The character of Squidward is basically an Incel archetype, before the Incel became a thing. At Slate, Christina Cauterucci uses Squidward as an example of a ‘millimeters of bone’ meme. If you’re not sure what that refers to, lucky you. Maybe stay well away.

INTELLECT JOKES

Every comedy needs a stoopid character. SpongeBob Squarepants is pretty stoopid, but Patrick is even stoopider. The jokes get funnier once we realise this is their ‘thing’. Expectation makes humour work even better. It works best when the stoopid character comes up with something even stoopider than the audience themselves can imagine.

The stupidness of Patrick is surprisingly simple and effective. When Patrick announces something which is blatantly untrue, my nine-year-old finds this hilarious. This ironic distance between what the viewer can see versus how Patrick interprets the situation creates an ironic distance which young viewers find very appealing. For instance, Patrick blows a bubble which looks exactly like an elephant. “It’s a giraffe!” he exclaims, making my nine-year-old giggle. [Update: The erstwhile nine-year-old is now a tween and has told her father to shut the hell up with this category of jokes, in fact all jokes, thanks.]

SOCIAL CAPITAL JOKES

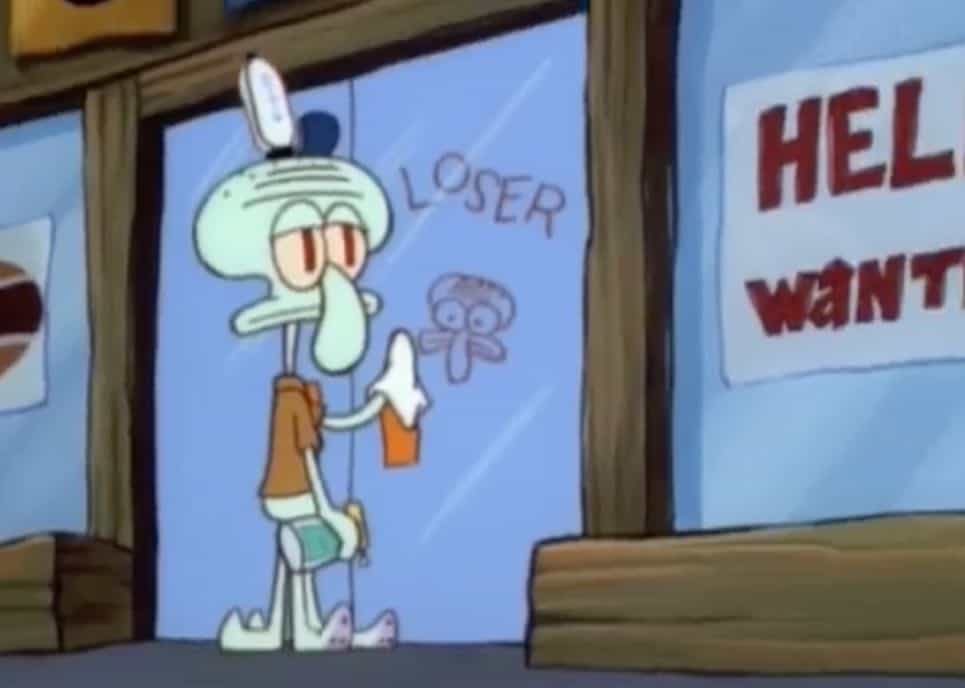

Squidward Tentacles is set up as the Loser character from the very first moment we meet him with this visual gag of him trying to remove some graffiti which won’t come off with rubbing:

Squidward’s nose has a phallic quality to it, drooping in disappointment or whenever his attempts to climb up the social hierarchy have failed.

Kids love making an unreasonably cranky character crankier. In Bubblestand there is a delight seeing the bubble elephant go inside Squidward’s house, disturbing his wind instrument practice. The audience is therefore reminded just how nasty Squidward is at the beginning of each episode. We are never trusted to remember, or rather, his nastiness gives us permission to laugh at him when he ends up in a full-body bandage or whatever. (The film Office Space uses the full-body bandage gag. Being live action, you’d think this’d be disturbing, except the guy who ends up completely incapacitated is wildly happy about it due to receiving compensation — an ironic reaction, hence the joke.)

There is literally no such thing as too many reminders that horrible character is horrible. Even when Squidward isn’t there, SpongeBob is making fun of him to impress Sandy Cheeks (in Ripped Pants). In Jellyfishing, Squidward is horribly sarcastic about not wanting to go jellyfishing with SpongeBob and Patrick. He suffers an accident on his bike and ends up in full body bandages. Patrick’s efforts to look after him end up with further injury to Squidward because of Patrick’s stupidity. Eventually Squidward is stung by an enormous jellyfish. Patrick and SpongeBob are stung by a smaller one so don’t get off scott free. I wonder if the writers thought dishing out all the bodily harm to Squidward and none to SpongeBob and Patrick was too much. I think they made the right choice. In the predictable and conservative sense of justice we all have as audience, SpongeBob’s naivety and Patrick’s stupidity did need punishing, just a little bit.

But because we’ve seen Squidward looking down on our empathetic characters, the writers do their absolute worst. Just when we think Squidward can’t be put through any more pain, the following day Squidward is in a bed on wheels rather than in a wheelchair. Now the audience needs a small reminder that this is cartoon violence. So they show us Squidward chuckling as the big jellyfish turns up again, like a classic horror creature that just won’t quit.

So that’s a case study in how to get away with extreme violence:

- Keep reminding the audience that the suffering creature deserves what they’re about to get

- Punish every character, according to their exact crimes, even the sympathetic ones

- Let the audience know that the terrible injury isn’t that bad.

3. REFERENCE HUMOUR

Reference humour refers to common experiences that the audience can relate to.

As mentioned above, a lot of the reference humour is specific to the heterosexual male experience.

On the other hand, NO ONE gets off scot free in this comedy — everyone is laughed at. But notice how Sandy doesn’t get to make her own jokes. Instead, she’s laughing her head off at SpongeBob. Only the male characters are allowed to be both funny and laughed-at. That kind of asymmetry for the girls — who are always the ‘straight guy’ yet just as often clueless — is what’s problematic here. This dynamic is closely related to the Female Maturity Principle of Storytelling.

There are jokes in SpongeBob which appeal to a mature audience but which safely pass over a child’s head. For instance, one episode opens with SpongeBob intently peering at some sort of tentacled sponge on his TV. When his snail cat walks by Spongebob declares that he wasn’t really watching that, he was only switching between channels.

4. SHOCK HUMOUR

In Ripped Pants, SpongeBob is trying to lift ‘weights’ (marshmallows on a stick) when he rips his pants in front of a much entertained audience. This is both reference humour and slightly shocking, in that it exposes a part of the body not normally exposed.

5. PARODY HUMOUR

The beginning of the Jellyfishing episode features a heist movie parody. Patrick and SpongeBob slide daringly down a rope but have to pause for a long moment to blow on their hands, which are burning in pain — something that never happens to ‘real’ cat burglars.

In the Something Smells episode SpongeBob eats a lot of onion and scares others away. He concludes he is too ugly to exist, at which point Patrick finds him in a dark place playing moodily on a grand piano, reminiscent of The Phantom of the Opera (even though I have never seen that).

In Plankton, a crabby patty pretends to be friends with SpongeBob in order to learn the secret recipe for crabby patties. The plankton baddie makes use of various technology to achieve his aim, including a mind-control device and another machine which tells him exactly what something is made of. He also has a gramophone, which he pulls into the scene whenever he needs some melodramatic music. This is meta humour, and the humour comes from the fact that extradiegetic sound effects are now diegetic. Not something the audience would ever put into words, but we realise the plankton thinks he is in some kind of crime movie, and is loving it.

SUPERHERO PARODY

Superheroes often have a getaway vehicle with some amazing power in its own right, be it a magic carpet, turbo rocket or whatever. In the final episode of the season one, Barnacle Boy and Mermaid Man also have a vehicle with superpowers, but that superpower turns out to be a hindrance rather than a help: it is totally invisible. This means they can’t find it when they want it. They walk into it, walk around feeling for it, and one of them is always getting burnt to a crisp because he accidentally stands behind the exhaust pipe. This ‘burnt to a crisp’ scene happens twice. The first time we see how he gets burnt — the second time he walks onto the stage already crispified, and we feel a little smart knowing how he got that way.

EXERCISE: Can you think of something that is sometimes a help to your characters but is also, more often a disadvantage, getting them into trouble? List all the ways in which they can get into trouble then take two or three and repeat.

The entire Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy episode is about underwhelming jobs for two superheroes, providing one long juxtaposition. At another point in the episode, they are called upon to open a jar for SpongeBob, who has previously been established as a comically weak character.

6. HYPERBOLE

Everything is over the top. So, SpongeBob doesn’t want to be late for his job interview? He’s set up a mechanical Wallace and Gromit type contraption to get himself ready in seconds. It even changes him out of his pants. SpongeBob is scared about the interview? He literally tries to run away as soon as he gets to the place. This is a blend of hyperbole and reference humour, because we all know how we’d like to run away whenever we feel scared.

SpongeBob doesn’t simply trip on a nail sticking out of the floorboards and fall over — he bounces and flips and enters into a never-ending series of smacks, where gravity doesn’t exist (unless it’s required for the scene).

Squidward doesn’t just get a minor injury catching jellyfish — his body is entirely covered in bandages and he wheels around on a gurney.

Sometimes a character gives the wrong (overblown) response to a situation:

“Make him feel good.”

“I love you.”

LAYERING

Sometimes, hyperbole means layering:

“I’m so old I’ve got hairs growing out of the wrinkles on my liver spots.”

7. WORDPLAY

WACKY NAMES

SpongeBob Squarepants itself is a wonderfully wacky name, as is Squidward Tentacles. Notice, however, that not all the characters have wacky names. Sandy Cheeks is kinda sexual. Patrick is aggressively ordinary. So is Gary. It’s this tension between weird names and normal ones that creates the humour — the difference draws attention to the wacky ones. These names also give us a clue about the character’s personality: While Patrick is often funny because he is stupid, he is always well-intentioned. In some ways he plays the ‘straight guy’, starting from the first time we see him, in which he gives SpongeBob a pep talk about how SpongeBob needs to go to his interview even though he’s terrified.

Sometimes wordplay involves drawing attention to language in a way that we may not have noticed before:

“The finest eating establishment ever established for eating!”

“Do you smell it? What’s the smell? A kind of smelly smell that smells… smelly!”

I have no idea why we find phrasal repetition hilarious, but it also explains Boaty McBoatface and all the subsequent snowclones.

Goo Lagoon

“This is my lab!” (Viewer expects to see a science lab but sees a dog) “And THIS is my laboratory!”

EMPHASIS ON NAMES OVER SUBSTANCE

When the recipe-stealing plankton throws seaweed into his ‘ingredients machine’, the machine tells him seaweed is made up of fifty percent sea, fifty per cent weed. This useless information, derived from the name of the product rather than the chemistry, foreshadows how useless the machine will be when trying to decipher what’s in a krabby patty.

EMPHASIS ON THE LITERAL MEANING OF PHRASES

“What? You’re off your rocker!”

‘Camera’ pans out to show an empty rocking chair beside the character.

Character sits in rocker and says the same thing again.Old man (Mermaid Man) buys ice cream from truck.

“A double scoop of prune with bran sprinkles,” he says, which is character humour to emphasis his oldness.

Next, “Goes right through me!” he exclaims. (The food shoots an actual hole through his middle.)

CHARACTERS MISUNDERSTAND WORDS

These work like puns but have no obvious antecedent.

SpongeBob: “We need to become entrepreneurs.”

Patrick: “Is that gonna hurt?”

8. JUXTAPOSITION

Juxtaposition is evident all over the setting, starting from the pet snail that meows like a cat. Another word for this is ‘surprise’. Yet we are not surprised at all, because in the real world, people tend to keep cats, not snails. A lot of the humour in this series comes from the writers and storyboarders pasting modern American life onto marine life — an awkward and funny endeavour.

I put any kind of ‘flip’ joke into this category.

Squidward is a more serious and adult character who occasionally reveals his childlike side by engaging in childish things like blowing bubbles when he thinks no one is looking. The juxtaposition between Squidward’s posing and his inner child provides plenty of humour. In this respect he’s like the Dwight Schrute character of the American version of The Office.

TRICKSTER FLIP

In the pilot, Squidward tells the boss SpongeBob is definitely not right for the position, but instead of a flat no, SpongeBob is sent on an impossible mission to find a thing that obviously doesn’t exist. (Obvious to the viewer, not to SpongeBob himself.) This is the restaurant owner being a trickster. Note that because this is the pilot episode, the audience doesn’t know that this particular spatula doesn’t exist. That’s why we see Squidward and the restaurant owner chuckling about its non-existence after SpongeBob has gone.

Takeaway point for writers: Don’t worry about being too obvious. Joke density allows an audience to accept over-explanations, on-the-nose narration and a host of other storytelling techniques eschewed by other genres.

But soon we’ll see that SpongeBob himself is a trickster, as he finds a way to fulfil his mission. He goes to the supermarket and, believe it or not, they only have one in stock. (Audiences of comedy will also happily accept this kind of deus ex machina solution to a problem.)

Audiences love tricksters, and we don’t mind who the trickster is. In this series, everyone has their turn outwitting each other with tricks, plans and wily scams.

9. MADCAP

SpongeBob doesn’t simply place meat patties onto the grill — he pings them out with his eye sockets. That’s just one example of many.

He regularly kills himself only to pop back up again. e.g. Slicing himself into thirds then immediately reforming into his character. He is literally indestructible.

His body morphs according to his emotions. Like Courage the Cowardly Dog, he can mould his spongey body into any shape that he likes. Whereas Courage does this once per episode, SpongeBob does it frequently, as the story sees fit.

10. META-HUMOUR

DELIBERATELY ON-THE-NOSE NARRATION

SpongeBob Squarepants as a series makes heavy use of what I’ll call ‘on-the-nose narration’. In a straight (non-comedic) story, having a character announce to no one in particular all about the scene and backstory is a definite no-no, but here it is totally accepted. This is almost a kind of parody on stories in general. The writers are asking, “Why are we even telling you all this stuff? Why are you even watching this made-up crap?” The answer, of course, is you’re watching it PURELY for the jokes. There is no higher reason for these stories to exist — no moral, nothing.

As an example, take the pilot episode. SpongeBob stands outside a restaurant and embarks upon a monologue all about the Crabby Patties, telling us that help is wanted and letting us know his reason for going in. (To get a job.)

Throughout the series, each episode is introduced by an ambiguously foreign-sounding narrator who invites us to remember that this is just a silly story and not to be taken seriously.

SATIRE OF HEIST/SPY STORIES

In one episode SpongeBob wears a disguise which is no such thing. Characters within the setting are fooled by his giant Afro wig and headband from the seventies, which is also so big it includes the filter of madcap.

SATIRE OF GET SMART/INSPECTOR GADGET ETC.

One episode features super spy equipment which is a pen that also turns into a pencil.

SPONGEBOB’S DIFFERENT VOICES

Related to this is one of SpongeBob’s character traits: While he has a ‘SpongeBob’ voice which we all recognise immediately, he regularly breaks out in a completely different voice (though voiced by the same actor). When he uses this voice he is usually parodying some other genre.

“I’ve been training my whole life for the day I could join the Krusty crew!” he says, flinging open the doors of the restaurant where he wants to get a job. Visually, this is like an old Western. In terms of dialogue, he is parodying any sort of ‘hero’s journey’ character arc, in which a boy (most often a boy) dreams of being something important and then achieves his wishes, but not without trials and tribulations.

11. MISPLACED FOCUS

Barnacle Boy and Mermaid Man are keeping watch on top of a tower, telling each other how they must always be prepared for when disaster strikes. Importantly, their dialogue comprises a list of cliches about being alert. But when SpongeBob turns up unexpectedly they fall off the tower in fright. That’s when we learn SpongeBob has only brought them donuts.

In Your Shoe’s Untied, the big reveal at the end of the story is that SpongeBob’s cat-snail has feet with shoes on, which we can only see if he lifts up his slimy body. We saw Gary the snail wander into the living room at the very beginning of the episode, so the story feels circular and complete at the end, when it is revealed that Gary is the only creature in Bikini Bottom who is able to tie shoes. Yet we never thought to look.

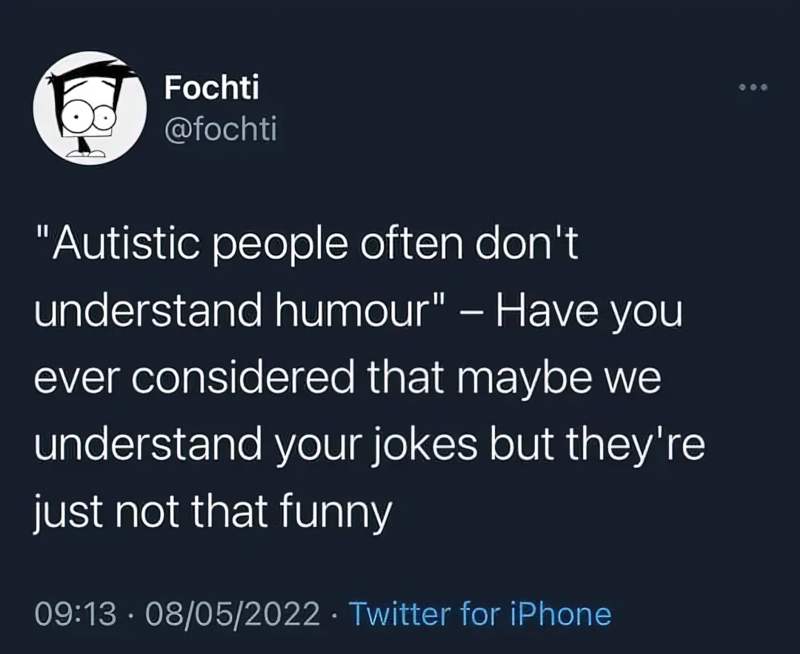

SPONGEBOB AND AUTISM

I hear so much from parents of autistic kids and caretakers of autistic kids, and this happens so much and comes up so often that somebody should write a term paper on it, that SpongeBob in particular is something that speaks to them. It’s the thing that they laugh at, the thing they obsess at, the thing they talk about and know every line of every episode […] And I don’t know what there is in that show that talks to kids that are on the spectrum, I don’t know, but more than other cartoons, that one … maybe because SpongeBob as a character is a little autistic. Obsessed with his job, very hardworking, gets really really deep into something.

Tom Kenny, voice of SpongeBob via the Marc Marron podcast, episode 324

Can SpongeBob be coded as autistic? Tom Kenny describes a stereotype of autism above. (Not all autistic people are obsessed with their jobs, for instance.) While Patrick is the ‘optimistic-happy-stoopid’ archetype, SpongeBob’s comic ‘stupidity’ takes a different form. When it suits the storyline, SpongeBob’s shortcoming looks more like social naivety/obliviousness. This is a gag utilised in the Netflix series Atypical (which I’m not recommending, for various reasons).

SOCIAL NAIVETY

This social naivety stands out in the Graveyard Shift episode.

SpongeBob doesn’t understand that Squidward is making up a scary story on the spot in order to scare him. There are plenty of clues for the audience, putting us in ‘audience superior’ position, a form of dramatic irony which is really enjoyable for kids, especially. Namely, Squidward has to ask SpongeBob what day it is today (Tuesday) before declaring that the spatula handed monster will be turning up today. Squidward is forced to admit he’s joking after SpongeBob won’t stop a lengthy bout of crying. But when SpongeBob learns he’s supposed to laugh, he laughs longer and harder than is natural or comfortable. As a consequence, Squidward is forced to be mean again to stop SpongeBob from laughing. It appears from this scene that SpongeBob behaves in a way that he feels he should, getting it slightly wrong he also fails to pick up he cues that Squidward is joking and needs to be told. This behaviour is known as ‘masking‘ among autists and perhaps explains why some of SpongeBob’s behaviours feel familiar, leading to an extra layer of reference humour for many viewers on the autistic spectrum.

The following gang of three ‘boys’ is pretty common in drama/comedy:

- One is neurotypical but an outcast for some reason (e.g. late puberty for Sam in Freaks and Geeks). This is the guy the audience identifies with. SpongeBob’s extreme shortcoming is the equivalent to Sam’s short stature.

- One is an over-confident but misguided skeeve. (That’d be Neal in Freaks and Geeks.)

- One could be coded as autistic due to his naivety and loveable innocence. (That’d be Bill from Freaks and Geeks.)

EXERCISE: We can paste this triad onto many shows. Try it for The I.T. Crowd or for Seinfeld. Or for kids’ books like Diary of a Wimpy Kid. It’s pretty obvious, right?

ALSO INTERESTING

It’s admittedly a stretch to identify parallels between Star Trek and SpongeBob, but the affinity is stronger than it might first seem. The cartoon’s core emotional triad contains powerful echoes of the anxiety-ridden three-way that gave Star Trek its homoerotic frisson.

Squidward, the new Spock

Stephen Hillenburg was partially inspired while creating the show after listening to Ween’s album The Mollusk. If you know the contents of those lyrics, you may be surprised at the juxtaposition.