Hud is a 1962 black and white film based on Larry McMurtry’s first novel, Horseman, Pass By. There is a connection to children’s literature here — Patricia Neal who plays the housekeeper was Roald Dahl’s wife. Neal had a severe stroke not long after this film was made. Her recovery meant she had problems with language. The made-up vocabulary of The BFG was inspired by Patricia Neal’s strange communication style after her stroke.

Hud is in many ways similar to Deliverance, appearing in American cinemas ten years later.

- Both are films based on novels

- Written by white American men concerned with themes of masculinity

- They both feature a stereotypical macho man whose bravado is also his downfall

- Both feature a small group of men in a terrible situation, wrestling verbally with each other to make a moral decision

- Each man of the group falls on a continuum from ruthless to morally upstanding

- The morally upstanding character is destroyed by his compassion and ends up in the grave

- While the macho man continues to ‘live’ but he has lost a part of himself, and his victory in getting his way is a pyrrhic one.

- Both are anti-Redemption Stories: “Hud was certainly a unique picture in many ways, but, most significantly, it dared to portray a central character who was a “pure bastard”—and who remained totally unredeemed and unrepentant at the end of the picture.” (William Baer)

Stories of this type continue to intrigue writers and readers.

Jeffrey Eugenide’s first book of short stories, published 2017, is also about men struggling with how to behave:

It’s sort of, you’re caught in the middle of this thing, you want to redefine what it means to be a man in our time, and then going along with that has to involve a lot of self-exposure, and a lot of recrimination and regret for your behaviour. At the same time, there’s maybe some resistance to being told how you’re supposed to behave. So the characters are caught between being good and being bad. That makes for more energetic fiction, when you have someone of two minds trying to figure out a problem, as opposed to being really sure about his way and his conduct.

Vulture

Genre Blend

Hud is not really a blend at all. Hud is a straight drama. You don’t find many of those on IMDb these days — most big films are a mixture of thriller/action/adventure and often with drama thrown in because of the character development.

At the time of release, Hud was said to be a contemporary Western. But here’s what the screenwriter’s response is to that:

BAER: Although Hud is clearly set in contemporary Texas, it’s often cited as one of the films that began the “demystification” of the American Western. It came out a year after The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, in which John Ford began to re-examine the Western hero, and it predated the so-called “revisionist” Westerns of the later sixties, like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) and The Wild Bunch (1969). I wonder how you feel about that?

RAVETCH: To be perfectly honest, I never thought of Hud as a Western. Never. I always thought of it as a domestic drama. Whenever I see Hud listed with Westerns, I wince. Not because I don’t admire Westerns—I wrote a number of them in my earlier days—but because I don’t feel the film is appropriate to that category.

Michigan Quarterly Review

The screenwriter, of course, is absolutely right. Hud is not a Western, nor is it even an anti-Western:

- It doesn’t use the metaphorical symbol web of a Western and nor does it subvert those symbols to make an anti-Western.

- It’s not about the taming of wilderness in order to build a home.

- It’s not about expansion of a nation, or the destruction wreaked under said expansion.

On the other hand, I can see where people might get to thinking this is an anti-Western.

- A Western has a lone warrior hero, leading a group of people to build a new village, and Hud seems like the ironic opposite of that guy.

- It’s set in cowboy country, where death is all around them

- There’s a category of Westerns set on a ranch, and the ranch comes under siege from outside forces.

- There’s a life and death struggle and a pyrrhic victory.

- Paul Newman starred in a bunch of Westerns and came to be associated with the genre. Larry McMurtry, too, also wrote anti-Westerns (later), as well as comical Western parodies, so was obviously influenced by the Western he grew up with when writing Horseman, Pass By.

Setting Of Hud

Place

Hud opens with various pan shots of a small, rural town. This is the fictional Texas town of Thalia, based on the small town where Larry McMurtry grew up, surrounded by uncles like the men in this story. The Last Picture Show was also set in Thalia.

Time

The grandfather is old enough to have lived through The Great Depression as an adult, and knows exactly how it goes down when cattle have to be slaughtered.

For the people living in the mid 20th century, war was a big part of their lives and influenced everything. They were never free from the threat of it, even after the second World War had passed. Here’s another similarity to Deliverance: the images of war in what is technically a non-war movie.

The story opens at the height of summer. It’s six in the morning and bright as midday. When the story ends it is still the end of summer, but dog days. The stench of the dead cattle would have been intense. Summer isn’t all about fun in the sun. For characters in stories, summer is a vulnerable time. In the summer, characters exist in:

- a troubled, vulnerable state or

- in a world of freedom susceptible to attack

Summer stands in symbolically for an snail under the leaf setting.

Characters Of Hud

Character Functions

While Hud Bannon (34 years old) is the title character of the film adaptation, I suspect the change in title is to do with the superstar crowd-drawing power of Paul Newman. The title of the novel suggests this is mainly the story of the old man. The ‘horseman’ of Horseman, Pass By would refer to Hud’s father, Homer, who is strongly connected to horses as a symbol of his tie to nature and simple needs.

“Horseman, Pass By, ” on which the film “Hud” is based, tells the story of Homer Bannon, an old-time cattleman who epitomises the frontier values of honesty and decency, and Hud, his unscrupulous stepson.

advertising copy for Horseman, Pass By

The old man’s tie to his horses contrasts with Hud’s pink Cadillac. Elvis Presley had a 1955 Pink Cadillac, cementing that car as the vehicle of choice for rock and roll wannabes and men-about-town. Because the film is black and white, we are told several times at the very beginning that this is a ‘pink’ Cadillac. A showy colour for a small town farmer.

Most Interesting Character: While Hud is a fascinating character, he is not the viewpoint/focalising character. We know a lot about Hud before we meet him. His nephew is looking for him, and the camera follows Lonny. Despite having lived in Thalia his whole life, Lonny’s function is similar to that of ‘the new guy in town’, because he is embarking on the new-to-him adult world that Thalia might offer. We follow Lonny as he tracks down Hud’s iconic car and then the woman’s shoe on the path, functioning like Hansel and Gretel breadcrumbs leading Lonny to his uncle.

Characters We Like The Most: We sympathise with Homer, who is a good man in a horrible situation. We also sympathise with the witty, attractive and world-wise Alma, especially when we learn more of her backstory, and see her sexually assaulted.

Viewpoint Character: Lonnie is the viewpoint character, obvious from the camera work in the film, but even more so in the novel, in which Lonny is the first person narrator. This is unusual for Larry McMurtry, who mostly wrote in third person. McMurtry has been accused of ‘head hopping’ but I disagree with that — instead, McMurtry probably switched to third person because he really wanted to move in and out of different characters’ heads. For me, he does it seamlessly, writing more like a novelist of the mid twentieth century than like a novelist of today, admittedly, where close third person point of view is the rule.

Off-stage Characters: Oftentimes, the characters who are missing from a story are nonetheless significant. Homer’s wife, Lonny’s mother and Hud’s older brother have all died, leaving these three men to form some semblance of family. For Alma, her missing character is her terrible ex-husband. The dead and missing family function as ‘ghosts‘ to the living (also known as the psychic wound).

Characters As Symbols For Ideas

When Larry McMurtry’s classic novel of the post-World War II era was originally published in 1961, it created a sensation in Texas literary circles. Never before had a writer portrayed the contemporary West in conflict with the Old West in such stark, realistic, unsentimental ways.

advertising copy for Horseman, Pass By

Old West in conflict with the New (mid 20th century) West. It’s not hard to fathom which character in this trio of men represents the Old West and which represents The New.

We sensed a change in American society back then. We felt that the country was gradually moving into a kind of self-absorption, and indulgence, and greed—which, of course, fully blossomed in the ‘eighties and the ‘nineties. So we made Hud a greedy, self-absorbed man, who ruthlessly strives for things, and gains a lot materially, but really loses everything that’s important. But he doesn’t care. He’s still unrepentant.

Screenwriter, Ravetch

Why Writers Can’t Trust Audiences

No matter how obvious you are.

Does this remind anyone else of the popular reaction to King of Assholes, Walter White?

FRANK: In our society, there’s always been a fascination with the “charming” villain, and we wanted to say that if something’s corrupt, it’s still corrupt, no matter how charming it might seem—even if it’s Paul Newman with his beautiful blue eyes. But things didn’t work out like we planned.

BAER: It actually backfired.

RAVETCH: Yes, it did, and it was a terrible shock to all of us. Here’s a man—Hud—who tries to rape his housekeeper, who wants to sell his neighbours poisoned cattle, and who stops at nothing to take control of his father’s property. And all the time, he’s completely unrepentant. Then, at the first screenings, the preview cards asked the audiences, “Which character did you most admire?” and many of them answered, “Hud.” We were completely astonished. Obviously, audiences loved Hud, and it sent us into a tailspin. The whole point of all our work on that picture was apparently undone because Paul was so charismatic.

Michigan Quarterly Review

Stark Good and Evil

While Lonnie is our more nuanced guide throughout this story, there’s nothing at all subtle about the goodness of Homer versus the amorality of Hud. The writing lesson from that: Don’t be afraid to overdo it. We are left in no doubt as to the nature of Hud:

- He has been in a brawl the night before, breaking a shopkeeper’s window

- He drives a big flashy car

- He’s spent the night sleeping with another man’s wife

- When the woman’s husband turns up he immediately blames his nephew

- He doesn’t want the government involved in the business of the sick cow, even though it would be unneighbourly and environmentally tragic to ignore the foot and mouth disease.

- “Sometimes I lean to one side of [the law], sometimes I lean to the other.” Hud tells the audience his philosophy of life.

- “How many honest men you know? You take the sinners away from the saints you end up with Abraham Lincoln.”

That’s just the first ten minutes. In contrast, Homer is a wonderful human being:

- He has concern for the health of his livestock as well as concern for the environment

- He does what is right and legal despite it ruining him

- He doesn’t blame Hud for the death of his other son, even though it was probably Hud’s fault (we see him driving)

- He is kind to Alma “It’s no reflection on your cooking Alma, I just don’t seem to have much appetite.”

- Black birds sitting in a gothically spindly tree are foreboding. Hud is bothered by he buzzards and shoots them away with his gun. “I wish you wouldn’t do that, Hud. They keep the country clean.”

- “You’re an unprincipled man, Hud.”/“Don’t let that fuss you, I mean you got enough for both of us.”

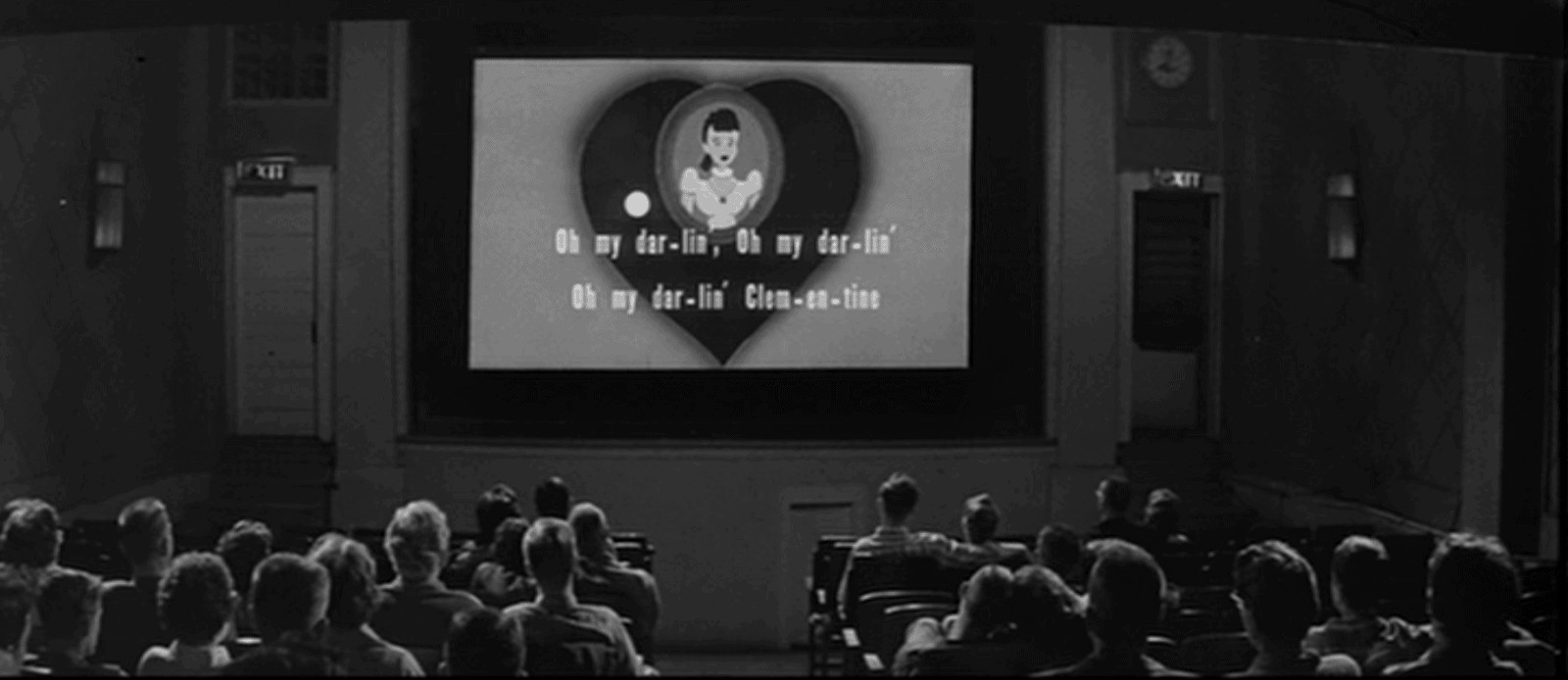

Homer has just learnt his entire livelihood hangs in the balance but he goes to the picture theatre with his grandson. The image of Homer singing loudly to the tragicomic song Oh My Darling Clementine is one of the most emotionally gut-wrenching for me, even worse than the slaughter of the cows, which is memorable but we know that’s coming.

The Romantic Subplot

Though this is a love tragedy rather than a romance or a love story, Alma’s existence shows us how Hud would treat a wife if he had one. For Lonnie, Alma is both a motherly and a sexual figure simultaneously — a hard thing to pull off without it being super creepy. This relationship Lonnie has with Alma shows the age Lonnie is at — still young enough to need a mother figure but old enough to be looking at women with sexual interest.

Larry McMurtry write women very well, considering he’s a man. Women do a lot of crying (though not Alma), and he does love women who go without shoes. He tends to write the same character over and over — Alma is a different outworking of Clara Allen in the Lonesome Dove series and of Molly Taylor in Leaving Cheyenne. (By the way, Leaving Cheyenne is the third novel in what’s known as McMurtry’s Southwest Landmark series — Horseman, Pass By and The Last Picture Show are the other books set in the same place at around the same time, linking together by their shared setting.)

Added to McMurtry’s understanding of women, the screenplay was written by a husband and wife team, which explains why the character of Alma is so well-drawn, so rounded and relatable. The screenwriting team of Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr met while working at MGM and had also collaborated on The Long Hot Summer (1958). After Hud, they wrote Hombre, Norma Rae, The Dark At The Top Of The Stairs and others. As you can probably tell, they were a good fit for Paul Newman.

My main point is that a woman on the writing team leads to better female characterisation. Every single time. A rounded character is especially important here, given the sexual assault scenes. When women are assaulted by men but are given no stories of their own, the violence feels egregious and exploitative.

What makes Alma ’rounded’?

- Alma has her own ghost — a former husband, a gambler, abusive. She’s had trouble with unwanted sexual contact in the past. She’s basically had to run away from her old life and thought she’d found a new family with these three men.

- Alma has her own shortcoming — she’s in a vulnerable position as paid employee, but more than that, she finds Hud attractive despite knowing how terrible he is.

- She has her own anagnorisis — the only way she can overcome her toxic almost-relationship with Hud is by removing herself entirely.

Story Structure Of Hud

Hud is an excellent example of a story driven by a strong moral dilemma. All the best stories have a moral dilemma at some point, but in this particular story the moral dilemma is central. Donald Maass explains the difference between a ‘dilemma’ and a ‘moral dilemma’. You need a moral dilemma for good narrative:

A dilemma is a choice between two equally good or two equally bad outcomes. A moral dilemma elevates such a choice by giving two outcomes equally excellent, or excruciating, consequences not only for a protagonist, but for others. A dilemma is a situation in which none of us likes to be caught, but in which we all sometimes find ourselves. A moral dilemma is a situation nobody wants, and which few must ever face, but which is terrific for making compelling fiction.

Donald Maass

In other words, dilemmas are a day-to-day thing but moral dilemmas are super big, important problems faced only by the unlucky few. Most of us never had to kill our entire livestock. Most of us never have to choose between keeping a son or a daughter (as in Sophie’s Choice).

One way of thinking about mystery comes from Karl Iglesias. In his book Writing For Emotional Impact, Iglesias recommends the following breakdown for creating mystery around characters:

Create a mysterious past Special abilities, secrets. Make the secrets hurtful and embarrassing or dangerous. Your character should be willing to do about anything to protect them.

Create a mysterious present Why is the character behaving in this particular way? Maybe they say something surprising in dialogue. The balancing act for writers is, these actions have to be both surprising and consistent with attitudes and desires. This is where the moral dilemma comes in. As soon as you create a fork in the road for your character this creates curiosity, anticipation and uncertainty in the reader. The mystery is: What on earth will this character do? The harder the choice, the more interesting it is to see the character’s decision.

Create a mysterious future What will be revealed about the character and when? How will the reader be surprised?— Writing For Emotional Impact

Check, check and check.

Hud’s mysterious past: He was responsible for killing his brother in a car wreck. He emerged without a scratch on himself. Turns out Hud is also a war veteran, though he did his darnedest to evade conscription. We never hear what happened to Hud during the war, but it wouldn’t have been great. So there’s his mysterious past (from Lonny’s point of view.)

The mysterious present is the question sustaining the length of the story: Do the cows have foot and mouth disease (we know that they do, because this is a story)

More interesting is Hud’s mysterious future: What is Hud going to do about this tragedy, given as how he’s such an unscrupulous asshole?

Other writers think in terms of ghost/psychic wound, setting up questions, rewarding with reveals.

It’s clear that the character function of Hud is as The Mysterious Character holding our interest. But is it really Hud who is facing the story-worthy moral dilemma? Ostensibly yes, but I’d describe Hud as I’d describe Donald Trump — this is a man whose morality was set long ago, and he’s on his own path. It’s up to everyone else around him to decide which way they roll. It is Lonnie who faces the moral dilemma of the ‘wrapper story’ — the metadiegetic level of story in which he comes to his anagnorisis at the end of the level zero story of the foot and mouth summer, but finishes his processing of it only after retelling. Lonnie must decide whether he’s going to stick by his uncle, becoming more and more like him, or set out on his own, risking everything he has left. The moral decision had by Lonnie is gradual rather than sudden. He doesn’t start the story knowing what’s right and wrong. At first Lonnie sits between Hud and his grandfather — Hud wants to sell bad stock to their neighbours; Homer wants to do the lawful thing, and Lon’s middle-of-the-road suggestion is that they turn the cattle loose. In case the audience is in any doubt about this: “You’re going to have to make up your own mind one day, about what’s right and what’s wrong,” says the grandfather to Lonny after the big struggle of words on the stairs.

Does Hud have his own anagnorisis? If he does, it’s a surface-level realisation that he’s losing people But this is not enough to make him change. He apologises to Alma only because he’s losing her, not because he’s discovered some truth about himself and life, the universe and everything. The tragedy of Hud is that he does not change. Hud is a precursor to Don Draper, having small, almost imperceptible revelations that don’t add up to much.

OPPONENTS

The Minotaur looming over this network of characters is the foot and mouth disease, personified by The Government, who are required to come in and kill their livestock.

Then we have a web of opposition between:

- Hud and Homer

- Hud and Alma (romantic opponents, morphing into abuser/abused relationship)

- Hud and Lonnie (annoying young one, cramping the stud’s style)

- Lonnie and Alma (between motherly interaction and sexual tension)

BIG STRUGGLE

In a story lacking a big big struggle (e.g. a war scene, a natural disaster, a big bad baddie descending on the group) you often get an image of a big struggle, connected to the main plot only symbolically. In Hud we have the pig fight in which Hud manages to adeptly catch a squealing pig. This allows Alma to say, “I’ll stay home. I don’t like pigs,” right after she’s turned Hud down for the second time (and presumably more times than that). It also gives us a good feel for the smalltown rural vibe – this is a very hick kind of entertainment. Hud is very good at catching pigs. This is a guy with skills, such as they are. The sport of pig catching also requires the switching off of empathy because I’m sure the pigs don’t like it, though that may be a personal response, borne of suburbia.

During the contamination experiment with the outside cow Lon is kicked in the head and is knocked out. He throws up. We now know that this can be a sign of brain damage. Hud doesn’t think Lon needs the doctor, though Alma does.

The pig fight foreshadows the brawl Hud enjoys getting into with the man in the bar. The men here are reduced to fighting pigs, fighting over nothing of consequence. Indeed, the men are set up to win. The pigs have no chance.

Lonny exchanges glances with a man’s daughter and enjoys the thrill of the subsequent barroom brawl as much as Hud does. At this point the nephew could swing either way, morally. On the cusp of manhood, he could let go of principles like Hud or he could hold onto them, like his grandfather. Even at this late point, we’re not sure what Lonnie’s going to do.

The main big struggle, the third one of the night, is the one that Hud finally loses. This ghost of Hud’s guilt at killing his own brother is used as a big reveal, though it’s basically been telegraphed earlier when Homer tells the boys to be careful and Hud hands Lonnie the keys. Hud learns that the grandfather was sick of him a long time before the car accident. It’s Hud, as a person, because he ‘doesn’t give a damn’, not because of something he did. This is the rule of threes in storytelling at work. The third big big struggle leads to the real wound. Compared to these words, the fisticuffs was just play fighting. The ironic distance between the level of physicality and the quietness of the conversation on the stairs works well as juxtaposition.

ANAGNORISIS

Homer has a anagnorisis before he dies — that he can’t win against his stronger, less principled son. Evil wins out.

Hud has superficial revelations, never changing.

Alma realises she has to leave physically if she wants to move on psychologically.

Lonnie realises he can’t stay with Hud:

“We might have whooped it up, you and me. That’s the way you used to want it.”

“I used to.”

NEW SITUATION

The extrapolated ending? We’ve been given enough information to know he’s going to get rich drilling into oil on their land. He will be wealthy but completely alone for the rest of his sorry life, damaged from the car accident, from the war, from toxic smalltown masculinity, from rejection from his father, from the death of his mother (“at least my mother loved me”) and rejection from his nephew protege.

The film uses the symbolism of doors and windows — Hud gazes at his nephew driving away, chuffing a smoke and swigging on a beer. These vices will probably play an increasing role in his life. He waves dismissively and slams the door, slamming not just the door but also punctuating the relationship he had with anyone.