If you want to start with the best of Carson McCullers, focus on the stories she wrote in the 1930s and 40s. Ill-health and issues related to alcoholism made it difficult for McCullers to keep producing the same high quality of life up until her death.

The most prevalent theme in the novels–rejection or unrequited love–repeats itself, as one might expect, in her short fiction. McCullers’s characters must learn again and again the lesson of eros, just as their creator herself had to learn it many times–and to live with it–over the years. The theme is firmly established in her apprentice story, “Sucker.”

Understanding Carson McCullers by Virginia Spencer Carr (1990)

Throughout McCullers’s canon, it is noteworthy that the children she depicts have no strong eemotional ties with their mothers. Lamar Smith believed that his sister “did not want to strip herself ‘that bare’ and reveal her utter dependency” on their mother. “Sister was too vulnerable,” he continued. “She was our mother’s favorite child, and somehow my sister Rita and I understood this. We were convinced that Sister was a genius, and that our mother was, also, for letting that genius flower.” McCullers’s fictional mothers–if they are mentioned at all–either die in childbirth, as does Frankie’s in The Member of the Wedding; are too preoccupied with helping to support the family when the father cannot, as does Micks’ in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter; drink too much, as does Emily Meadows in “A Domestic Dilemma”; or attempt suicide, as does Hugh’s in “The Haunted Boy.” On the other hand, the fathers in her fiction are treated rather compassionately. Like Mick’s and Frankie’s fathers, they suffere because they fail to communicate with their daughters, who are only vaguely aware of their sense of loss and appear reticent to deal with them directly.

Understanding Carson McCullers by Virginia Spencer Carr (1990)

Most of the latent love relationships in McCullers’s short fiction never reach maturity, and for good reason. As her narrator expressed it in The Ballad of the Sad Café (and evident, as well, throughout her writings), “The value and quality of any love is determined solely by the lover himself,” and such myopic vision by very nature destines one’s love to go unnoticed or bitterly unrequited.

To McCullers, a lover was always vulnerable unless he loved someone — or some thing — from whom he expected nothing in return. In “A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud,” a beery tramp confides to a pink-eared newspaper boy, a stranger to him, his “science of love,” which he conceived after being abandoned by his wife. The tramp’s sterile formula has led him to love things that cannot love back–first, a goldfish, then a tree, a rock, a cloud. But he invites the catcalls of mill workers in the all-night café in which he accosts the child and tells him: “Son! Hey Son!… I love you”. Despite his declaration, the tramp knows that he can walk out alone into the predawn silence and never see his so-called “beloved” again. Loving a woman is the “last step” to his science, he tells the boy. “I go cautious. And I am not quite ready yet”. The reader feels intuitively that the dissolute tramp will never be ready for the final step. He will not risk vulnerability to eros.

Understanding Carson McCullers by Virginia Spencer Carr (1990)

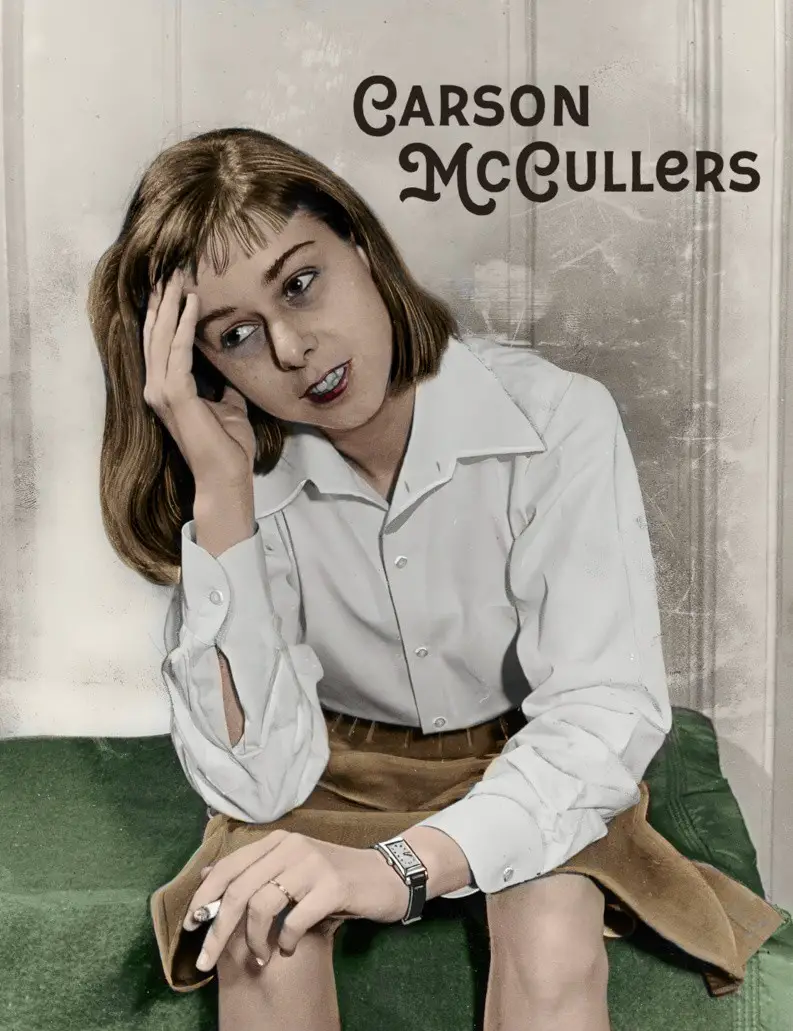

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

Just as well Carson McCullers started young because they also died young. The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter was published in 1940 when McCullers was only 23. The success of this novel propelled them into the realm of a Great American novelist.

Carson McCullers has a few big things in common with John Cheever. Both were alcoholics, both were bi plus.

McCullers suffered from ill-health. They had rheumatic fever at the age of fifteen, though doctors thought it was pneumonia with complications. This weakened their heart, which had the knock-on effect of causing strokes. Because of strokes they lost vision in one eye and had complete paralysis on the left side of their body. McCullers smoked between two and three packets of cigarettes per day. They were also a day-long drinker.

Recently uncovered letters reveal that Carson McCullers was (at least briefly) in love with Marty Mann, considered by some to be the first woman with long term sobriety in Alcoholics Anonymous. However, Marty already had a (woman) partner and had to turn McCullers down.

This probably applies to most novels which become classics (with the exception of Truman Capote, who had an ego to match his success), when Carson McCullers wrote The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter, they had absolutely no idea it was going to become the success that it did. (Likewise, the characters in the novel have no idea that war is about to break out just one week after the end of the novel.)

GENDER AND NEURODIVERGENCE

McCullers never commented directly on their gender and sexuality. Commentators have since noted that McCullers seemed at least emotionally oriented towards women. In the 21st century we may say homoromantic to describe this orientation.

Many neurodivergent people are also genderqueer to the point where one cannot be prized apart from the other, hence the term neuro-queer.

I have made the decision to use they, them pronouns for Carson McCullers, who may have chosen non-binary pronouns had they been born in an era in which this were even an option. Of course, that’s not for certain. I consider they, them neutral, partly because I come from New Zealand, where they, them serves as a perfectly concordant singular pronoun these days.

There’s plenty to suggest Carson McCullers may have been genderqueer.

Carson McCullers was named Lula Carson Smith at birth. Their mother had been expecting a gifted boy due to some fortune teller. The mother was correct about the giftedness, but got a girl instead. Carson dropped “Lula”, ostensibly because their cousins teased them about their double name, but was this also because Carson is less feminine? Perhaps the reason for the taunts was more the observation that someone like Carson McCullers did not suit a girly name such as Lula.

Carson’s siblings were seemingly happy to admit that Carson was their mother’s favourite. Carson was the special child, even from before birth. This was probably very isolating for Carson. There are advantages to being the favourite, but the expectations weigh heavy, and being the Special One is ultimately isolating. Biographers tend to blame Mrs Smith for socially isolating her child from peers, preventing Carson from making friends.

I put it to you that Mrs Smith, like all mothers of her generation, was blamed for Carson’s (highly probable) neurodivergence. Today we might call Carson Autistic. Perhaps it was neurodivergence, not Carson’s mother’s high expectations which led to their isolation as a child.

Autistic people have very little time for rubbish social rules which make no sense. Now here’s what we know about Carson:

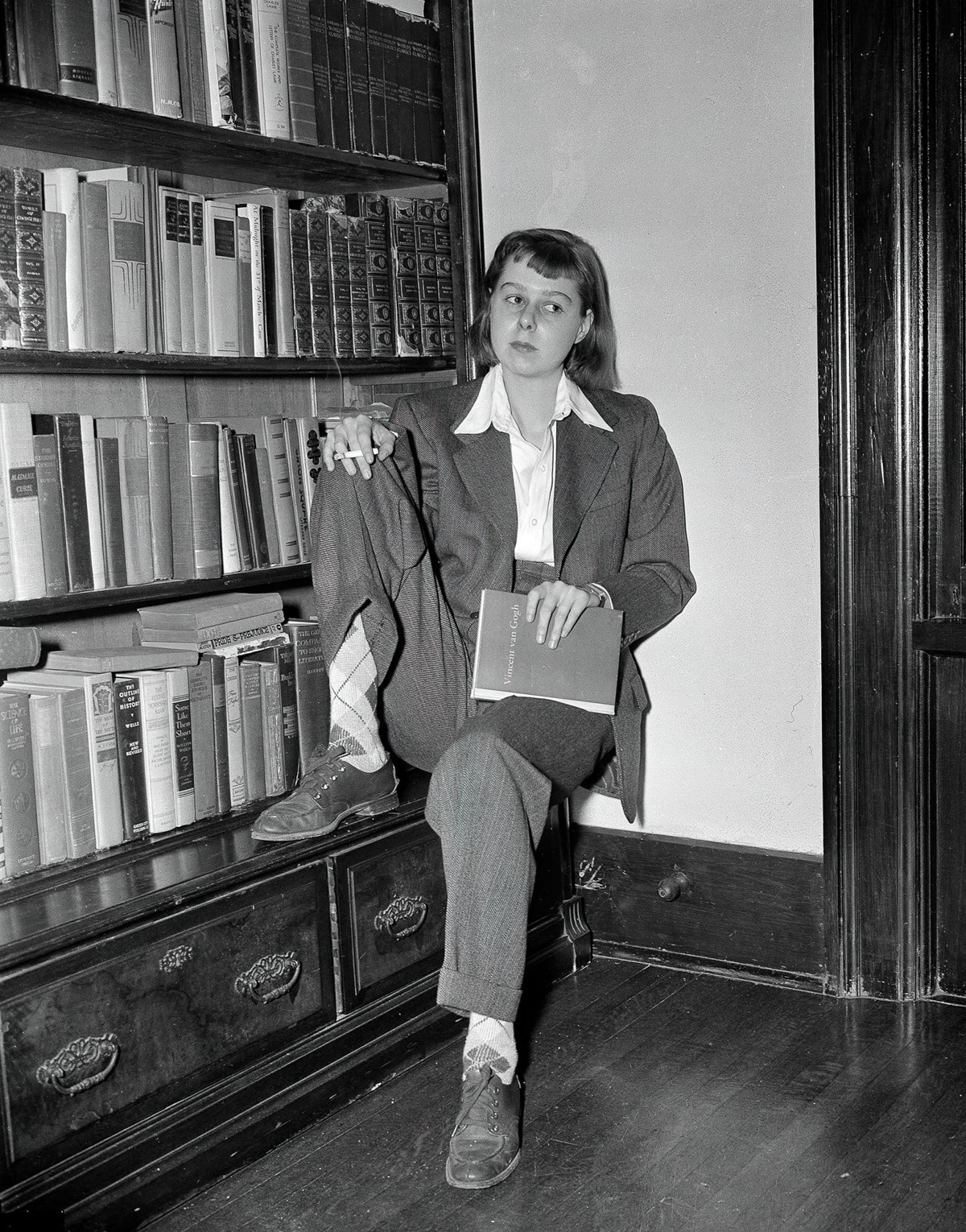

- Carson’s classmates all wore stockings and heels. Carson wore tennis shoes or Girl Scout oxfords instead, probably because they were far more comfortable. (Autistic people don’t wear uncomfortable clothing just to fit in. Sensory issues frequently override everything else.) Carson also wore boys’ white shirts and changed them three times a day.

- Carson didn’t care about grades. Although gifted, this didn’t come through in results, not even in writing. If they didn’t see the point of an exercise, they did the bare minimum. Carson’s mother queried one of Carson’s English teachers why Carson hadn’t been given better grades. The teacher knew Carson was capable of much more, but until Carson decided to put effort into assignments, better grades could not be given. (It is very difficult for Autistic (and ADHD) people to simply decide to direct attention towards something without seeing a point.)

- As an adult, Carson dressed ‘garishly’, meaning, they dressed in socially unexpected ways.

- Like any accomplished musician, Carson spent many hours practising. Reading, writing, practising piano. This was Carson’s happy space, and probably a very necessary part of their life, away from the pressures of social expectations.

- Carson was agoraphobic, which heightened during their time at university taking creative writing classes. (Autism frequently goes hand-in-hand with agoraphobia.)

At Talk Nerdy, Comedian and author Sara Benincasa (“Agorafabulous“, “Great“) opens up to Cara about her struggles with mental illness, including debilitating agoraphobia, and the importance of comedy in our lives.

- Carson married Reeves McCullers in 1937. The marriage lasted until 1942. It’s difficult for outsiders to catalogue reasons for a break-up, but a close friend of them both, David Diamond, put it like this: “Carson did not even seem aware that she had rejected Reeves to the extent that she was now losing him. She appeared far more interested in everything else going on about her, in the celebrities she was meeting, in the hangers-on, in her pseudofriends who swarmed about her. Although her work of course, took her away from Reeves, at least 75 per cent of it was caused by people. Charmed by a smile, adulation, or kind remark, Carson at this time loved almost everyone she met.” It sounds to me like Carson became hyperfocused on fame itself. It also sounds like she struggled to know genuine friendship from the illusory kind, which is interesting, given that they explored this theme in their writing — possibly as a way of analytically thinking through their own relationships in real life. Reeves held the household together while Carson was busy being famous. It was actually Carson who divorced Reeves when they realised he’d been forging their cheques. But that was the last straw. They’d been separated numerous times before that. Then they got remarried as the war came to a close. Eleven years later Carson filed for divorce once again and Reeves ended his own life.

- Once Reeves died, Carson rarely spoke of him, and when they did, spoke of him disparagingly. Close friends believe Carson and Reeves were a great love story, and that Carson probably didn’t recognise it as such. Once Reeves was gone, he was gone. In this respect, Carson reminds me very much of Edward Gorey, who I also believe was Autistic (and neuro-queer).

- The other main person in Carson’s life was a Swiss woman called Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach. Carson dedicated Reflections of a Goldeneye to Annemarie. I highly recommend looking Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach up, because Their Life Was Stranger Than Fiction. People observed that Carson had a ‘monomaniacal’ fixation with Annemarie. (Annemarie was Carson’s special interest.)

One of Schwarzenbach’s most heated and tumultuous relationships was with the American author Carson McCullers, whom she met while traveling in the United States in 1940. McCullers was captivated by her appearance. Hilton Als wrote in the New Yorker, “Schwarzenbach had the kind of androgyny and physical fearlessness that McCullers most admired.” McCullers became obsessed with Schwarzenbach. In conversations with her psychiatrist, she talked about Schwarzenbach endlessly, every anecdote reminding her of something Schwarzenbach said or did. Of the seven transcripts of her sessions, Schwarzenbach is the subject of five. In her unfinished autobiography, she wrote, “I don’t know of a friend whom I have loved more.”

Androgyny was the power and the curse of the tragically glamorous writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach

- Carson also fell deeply in love with writer Katherine Ann Porter (not reciprocated in the slightest, not even when Carson lay down across Porter’s front door, meaning Porter had to literally step over Carson to go out for dinner).

- Injustice sensitivity is a feature of autism. Carson was extremely sensitive to other people’s pain, avoiding the freak show which came to town as a child even though that was the thing to do.

STYLE

Carson McCullers was a musician as well as a writer. Read it aloud and you’ll find this shines through in the rhythm of their sentences. Critics such as Barbara C. Gannon and C.M. Smith have noted similarities between McCullers’s mechanical structure and musical scores.

use of THE GROTESQUE

Carson McCullers made use of the grotesque.

Nowadays, when people talk about “the grotesque,” their meaning is closer to its adjectival form: “very strange or ugly in a way that is not normal or natural.” The grotesque in literature focuses on the human body, and all the ways that it can be distorted or exaggerated: its aim is to simultaneously elicit our empathy and disgust. Very much like the uncanny, the grotesque draws its power from the combination of the familiar and the unfamiliar, or the familiar distorted. Gothic fiction often has elements of the grotesque, such as Mary Shelley’s monster in Frankenstein or the off-kilter characters in Flannery O’Conner’s [and Carson McCullers’s] stories.

The Masters Review

SETTING

Carson McCullers came from Columbus, Georgia, which is near the Alabama border.

Most critics consider McCullers from the “Southern school” of writers, but McCullers had a complicated relationship with the American South. They dreamed of leaving the South and never returning, drawn to big cities such as London and Paris. They finally escaped the South in 1934, and never returned on a permanent basis, but she was forced to return so her mother could take care of her during a bout of bad ill-health. They also quipped this visit back renewed their sense of horror.

McCullers set most of their novels and stories in a provincial town somewhere in the Deep South. (The term Deep South was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery during the early period of United States history. The Deep South stretches from Louisiana in the West to South Carolina in the East.)

These towns are populated with eccentric, dislocated and lonely people.

STORY STRUCTURE

McCullers clearly understood the expected structure of normative storytelling, then went out of their way to reject them. For example, The Member of The Wedding might suggest, on a surface level, that Frankie wants to get married. (She wants no such thing.) On a deeper level, readers might assume that Frankie wants to assimilate with the married couple, since she wants to be a ‘member’. (Again, there’s no evidence she wants any such thing.)

A Member of the Wedding is an inversion on an expected Bildungsroman, which started out as a young man’s coming-of-age, and then for young women was modified to tell the story of the journey towards marriage. Instead, McCullers writes of Frankie’s rich fantasy life, and creates a main character who can’t seem to even remember her own recent history. Omniscient narration shows Frankie constantly circling back on herself. This is no linear journey towards adulthood. A Member of the Wedding is not a Bildungsroman at all, but is instead a white girl’s struggle to deal with the oppressive gender and racial norms of her time.

CHARACTERISATION

A WHITE WRITER, BLACK CHARACTERS

To me the most impressive aspect of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter is the astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern fiction, to handle Negro characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race. This cannot be accounted for stylistically or politically; it seems to stem from an attitude toward life which enables Miss McCullers to rise above the pressures of her environment and embrace white and black humanity in one sweep of apprehension and tenderness.

Richard Wright, The New Republic, August 5, 1940

McCullers had an uncanny ability to empathise with people of colour, at odds with her background as a white person living in an especially racist. McCullers self-identified as different from an early age and experienced significant empathy for anyone considered different.

INJUSTICE SENSITIVITY

We all of us somehow caught. We born this way or that way and we don’t know why. But we caught any how. I was born Berenice. You Born Franky. John Henry born John Henry. And maybe we wants to widen and bust free. But no matter what we do we still caught. Me is me and you is you and he is he. We each one of us somehow caught all by ourself. I’m caught worse than you is. Because I’m Black, because I’m colored.”

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

In their unfinished autobiography they wrote about seeing first hand the humiliation experienced by the Black domestic help. In that, they recall an incident in which a Black domestic employee called a taxi to come pick her up to go home after work in a white neighbourhood. When the taxi pulled up, the white taxi driver refused to take her home and drove away. Watching on, Carson and their brother experienced such terrible second-hand humiliation that they crawled under the house and stayed there for a long time, coming to terms with what they had just seen.

In the early 2020s, the current expectation is that white writers should not attempt to create Black characters in their work. Authors such as Zadie Smith and Lionel Shriver push back against this expectation, and sometimes refer to Carson McCullers as a white writer who did it well. (Zadie Smith pushed back in The New Yorker, in an article called “White Writer“.

It may be the case that Carson McCullers got things wrong about Black experience but because she wrote before this discourse was taking place, has so far mostly escaped criticism. She may get away with this partly due to her choice of narration. She might be criticised for describing the way a Black neighbourhood smells (noticeable only to a non-Black writer), but she puts it on the page through the point of view of Mick, a white character. This makes the character realistically racist, not the author.

Jake and Singer waited on the front porch. When they pushed the doorbell there was no sound of a ring in the darkened house. Jake knocked impatiently and pressed his nose against the screen door. Beside him Singer stood wooden and smiling, with two spots of color on his cheeks, for they had drunk a bottle of gin together. The evening was quiet and dark. Jake watched a yellow light shaft softly through the hall. And Portia opened the door for them.

‘I certainly trust you not been waiting long. So many folks been coming that us thought it wise to untach the bell. You gentlemens just let me take you hats–Father been mighty sick.’

Jake tiptoed heavily behind Singer down the bare, narrow hall. At the threshold of the kitchen he stopped short. The room was crowded and hot. A fire burned in the small wood stove and the windows were closed tight. Smoke mingled with a certain Negro smell. The glow from the stove was the only light in the room. The dark voices he had heard back in the hall were silent.

The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter

WHAT DO CHARACTERS WANT?

McCullers’s characters want to belong. They want to belong so very much, they’ll fall for the wrong people, thinking the objects of their desire are so much more worthy than they eventually show themselves to be.

QUEER ABJECTION

McCullers is able to project herself into her characters, but she still seems restricted in allowing them to come out or to confront these desires and figure out what the desires mean in relation to their lives. Jan Whitt sees…that “while McCullers critiques queer abjections, she certainly does not take the next step of celebrating the pleasures of queer love, sexuality, community, or identification. This can be explained by Kristeva’s explanation of the desire to confront the abject while simultaneously being disgusted by it and wanting to hide it.

Veiling with Abjection: Carson McCullers’ Reflections in a Golden Eye by Sarah Beth Gilbert

One may wonder how much credit we should give to McCullers for being progressive on the subject of gender. In Sarah Gleeson-White’s book Strange Bodies: Gender and Identity in the Novels of Carson McCullers, she points out that McCullers’s sometimes vague and sometimes stereotypical portrayal of homosexuality can be damaging in combination with a novel that portrays the queer as grotesque. However, Gleeson-White also gives credit to McCullers that “her discernible struggle to depict a new configuration of homosexual desire, which is productive, testifies to the difficulty of her radical project and forces us to think more deeply about gender’s complex relation to bodies and sexuality”. This statement is completely true and supportive of the fact that historically it would have been hard for McCullers to push the boundaries any further than she did, and that the complexity of sexuality that she experienced is represented in her writing.

Veiling with Abjection: Carson McCullers’ Reflections in a Golden Eye by Sarah Beth Gilbert

ADOLESCENT CHARACTERS

[McCullers] created a wide array of adolescent and pre-adolescent characters who encounter difficult and sometimes violent circumstances that force them to grow up before they are ready to do so. McCullers creates distinct boundaries between the world of the adolescent and the world of the adult.

Ashley-Ann Woods, Adolescent Transformation in the Short Stories of Carson McCullers

FATHERS

McCullers didn’t write loving, rounded fathers, though some say an exception is Mr Brown of “The Haunted Boy“. (I believe Mr Brown is another example of an emotionally repressed man, though he is a ‘successful’ version of 1950s hegemonic masculinity.)

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL INCOMPLETENESS

To do with the idea that someone who isn’t in love cannot be complete, Carson McCullers’s work is filled with characters who are physically and mentally incomplete as well. McCullers said that the defects in their characters symbolise the “spiritual incapacity to love or receive love”.

MCCULLERS VS FAULKNER

Carson was writing in the wake of William Faulkner. (They lived at the same time, in fact.) When Faulkner writes African American characters he seems to be putting them on the page for exhibitionist purposes. In contrast, McCullers really gets deep into the psyche, thereby treating Black characters in a very human way.

Out of the tradition of Gertrude Stein’s experiments in style and the clipped, stout prose of Sherwood Anderson and Ernest Hemingway comes Carson McCullers’ “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter.” With the depression as a murky backdrop, this first novel depicts the bleak landscape of the American consciousness below the Mason-Dixon line. Miss McCullers’ picture of loneliness, death, accident, insanity, fear, mob violence and terror is perhaps the most desolate that has so far come from the South. Her quality of despair is unique and individual; and it seems to me more natural and authentic than that of Faulkner.

Richard Wright, The New Republic, August 5, 1940

MCCULLERS VS FLANNERY O’CONNOR

Perhaps because of gender, and because the culture loves to pit “women” against each other, these two writers are frequently compared and contrasted. They are, of course, both Southern. They also both write evocative descriptions of Southern settings.

Frank Baldanza said that both writers create “parables on the nature of love”. This critic included McCullers in the same group as William Faulkner, Truman Capote and Eudora Welty.

THEMES

WRITE WHAT YOU KNOW?

McCullers had an interesting take on advice to ‘write what you know’:

A teacher once said that one should write about one’s own back yard; and by this, I suppose, she meant one should write about the things that one knows most intimately. But what is more intimate than one’s own imagination? The imagination combines memory with insight, combines reality with the dream.

Carson McCullers

CENTRAL THEMES

- Love hurts

- Loneliness hurts

- You can still be lonely even when you’re in love

- Normality is tyranny

- Queerness and freakishness as ways of breaking free from tyranny

McCullers was a writer who kept up with political issues of their day. Sometimes they said something about their own work which baffled critics. For example, of The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter, McCullers described it as “an ironic parable of fascism.” Critics are still scratching their heads over that one. (I wonder if McCullers was shit-stirring.) They also said this:

Spiritual isolation is the basis of most of my themes. [The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter] was concerned with this, almost entirely and of all my books since, in one way or another. Love, and especially the love of a person who is incapable of returning or receiving it, is at the heart of my selection of grotesque figures to write about — people whose physical incapacity is a symbol of their spiritual incapacity to love or receive love — their spiritual isolation.

The Flowering Dream: Notes On Writing by Carson McCullers

The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter is more clearly a Depression novel, and one of the last.

Was McCullers pessimistic about love, since it so often fails between their fictional characters? Well, their characters at least give it a go. Better to have loved and lost… Also, you could argue any romance genre writer is a pessimist who just so happened to finish the novel when characters were at their happiest.

Ultimately, Carson McCullers strived for ‘communion’ between people. McCullers was interested in illusion versus reality. Relationships fail because they’re based on illusion. Two types of love: passionate and spiritual. Passionate lovers invent their own love, based on illusion. But spiritual love is the real kind. Spiritual love involves “a new inward world — a world intense, strange and complete in [themself]”.

The spirit does not have a gender, so spiritual love has nothing to do with the gender of the person you love. For McCullers’ characters, spiritual wholeness happens once the passion around sex is out of the way. Across McCullers’s work, look out for characters who think they’ve found spiritual love but they’ve really only found passionate love.

CHAT GPT WRITES A CARSON MCCULLERS SHORT STORY

To test its capabilities, and mostly for fun, in February 2023 I asked Chat GPT to “Write an original short story in the style of Carson McCullers.” I wondered what AI would pick up as distinctively ‘McCullers’. Here’s what it came up with:

The town was small and quiet, with streets lined with old oak trees and houses that had been standing for over a hundred years. It was a place where everyone knew each other’s names, and life moved at a slow and steady pace.

Lena lived in one of these houses, a small cottage on the outskirts of town. She was a solitary person, and she spent most of her days lost in thought, looking out of the window at the world passing by. Lena had always felt like an outsider, as if she didn’t quite fit in with the rest of the townspeople.

One day, a new family moved into the town, and Lena couldn’t help but be curious about them. The family was different from anyone she had ever met – the mother was blind, and the father was a writer who spent most of his days locked away in his study. They had a son, who was unlike any child Lena had ever seen. He was quiet and reserved, with a sadness in his eyes that Lena couldn’t shake.

Lena was drawn to the boy, and she found herself spending more and more time with him. They would sit in silence, watching the world go by, and Lena felt a sense of comfort in his presence. Over time, they grew closer, and Lena found that she was opening up to the boy in ways that she had never opened up to anyone before.

One day, the boy told Lena about his mother’s blindness, and how it had affected their family. He told her about the sacrifices his father had made for his mother, and the love that had kept them together despite their difficulties. Lena was moved by his story, and she realized that the boy was someone who truly understood the complexities of life.

As the months went by, Lena and the boy grew even closer, and Lena found that she was beginning to see the world in a new way. She was filled with a sense of hope and joy, and she realized that she had finally found the love and understanding that she had been searching for.

Lena and the boy spent the rest of their days together, exploring the world and discovering the beauty in the simple things. And as they sat together, watching the sun go down, Lena knew that she had found her place in the world – with the boy, who had shown her the meaning of love and acceptance.

I wasn’t after a cheesy love story, so I asked it to try again:

The sun was setting, casting a warm golden glow over the small Southern town of Millfield. Lila sat on her porch, sipping sweet tea and watching the world go by. She had lived in Millfield all her life, and she knew every person and every street, but she still felt a sense of restlessness.

Lila had always felt like an outsider, even among the people she had known all her life. She was different, and she didn’t quite fit in. As she sat on her porch, she saw a figure walking down the street, and she felt her heart quicken.

It was a young man, a stranger to the town. He was tall and slender, with a sad expression on his face. Lila felt a pull towards him, and she couldn’t explain why. She watched as he stopped in front of her porch, and she felt a sense of anticipation.

The young man looked up, and their eyes met. Lila felt a jolt, as if she had found a piece of herself that she never knew was missing. The young man introduced himself, and they struck up a conversation. He was a musician, passing through town on his way to the city.

As they talked, Lila felt a sense of connection with the young man. They shared a love of music, and they both felt a sense of longing for something more. They talked long into the night, and Lila felt as if she had finally found a friend who understood her.

The next day, the young man left town, and Lila felt a sense of loss. But she also felt a sense of hope, as if she had found a part of herself that she never knew was missing. From that day on, Lila dedicated herself to pursuing her passion for music, and she felt a sense of happiness and purpose.

Years went by, and Lila became a successful musician, traveling the world and playing to sold-out crowds. But she never forgot the young man she had met in Millfield, and she felt a sense of gratitude for the chance encounter that had changed her life.

Nope, that’s a Nicholas Sparks plot.

FURTHER READING

- The Carson McCullers Center’s Weekly We Of Me podcast

- Understanding Carson McCullers by Virginia Spencer Carr (1990)

My Autobiography of Carson McCullers

Jenn Shapland’s My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Tin House Books, 2020) is a fascinating cross-genre book that combines elements of traditional biography with Shapland’s own personal narrative of researching McCullers and discovering the many ways her life and McCullers’ mirror each other. McCullers was a lesbian, but many of her biographers have shied away from this aspect of her life, referring to her partners as “friends” or “obsessions.” Shapland’s book is a bold work of historical reclamation, insisting we view McCullers as a queer writer and drawing attention to previously-obscured elements of queerness in her work. It is also a portrait of a vibrant queer community existing beneath the placid surface of mid-century America: Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Gypsy Rose Lee, and W.H. Auden all make memorable appearances in its pages. My Autobiography of Carson McCullers is a must-read for fans of McCullers, but it will also be of interest to fans of cross-genre writers like Maggie Nelson, Eileen Myles, and Hilton Als.

New Books Network