**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

Of course, no one but Alice Munro can write like Alice Munro. That is my disclaimer on each of my sporadic series of ‘How To Write Like…’ posts.

If you read a lot of Munro’s works carefully, sooner or later, in one of her short stories, you will come face to face with yourself; this is an encounter that always leaves you shaken and often changed, but never crushed.

Peter Englund, in the Nobel Prize presentation speech

Which Munro story is your ‘shaken but not crushed? I think I know mine, but I’ll keep that to myself.

When Margaret Atwood was selecting short stories for a Best of collection around 1989, Atwood asked for stories to be presented to her with names blacked out. She didn’t want to know who had written them, instead choosing them entirely on merit. However, as soon as she started reading Alice Munro’s short story, she knew immediately who had written it (along with the Mavis Gallant story). Both authors are one of a kind and utterly distinctive.

WRITING PROCESS

Alice Munro has stopped writing now, but she found the work of being a housewife compatible with writing. Housework occupies just the right amount of brain, and is sufficiently mundane to let the gates of creativity open. She nutted many of her stories out while caring for three young daughters. The stories would be well developed before she wrote them down. Munro has never resented housework. She’d been doing significant amounts of it since her early teens after her mother was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. “It gave me a sense of responsibility, purpose, being important. It didn’t bother me at all.”

READING PROCESS

If we really wish to understand how Alice Munro sees story, it helps to know how the author herself reads other work. She doesn’t read from beginning to end!

I don’t take up a story and follow it as if it were a road, taking me somewhere, with views and neat diversions along the way. I go into it, and move back and forth and settle here and there, and stay in it for a while. It’s more like a house. Everybody knows what a house does, how it encloses space and makes connections between one enclosed space and another and presents what is outside in a new way.

Alice Munro, 1982

This suggests that Munro enjoys most the out-of-context flashes of scenes and insights rather than, say, the page-turning qualities of certain genres.

HOW DOES A STORY START?

“Almost any old way at all that I can get into it.”

In interviews, Munro has mentioned that her stories are “elaborations and combinations” that may be difficult to trace back to their original sources.

SELF-EDITING

Munro is well-known as an endless self-editor. She has even paid a penalty fee for insisting on edits after a story has been sent off for printing. (The story was “Who Do You Think You Are?” which she changed from first to third person narration.)

She insists on editing things even when editors disagree that a story needs any more further work.

When she does readings of her own early work in front of an audience, she finds it very difficult not to change the words as she reads. She realises she no longer writes as she did when she first started out.

Every word in an Alice Munro story is doing work. Deborah Treisman, the experienced New Yorker editor and host of The New Yorker Fiction podcast, has shared that she sometimes crosses something out in a Munro story only to realise a few pages later that the sentence is doing a lot of work and must be left in.

There’s never a false or fussy note.

Tessa Hadley

It is a challenge to find an unessential word or a superfluous phrase. Reading one of her texts is like watching a cat walk across a laid dinner table. … She is a virtuoso of the elliptical.

Peter Englund, in his presentation speech when Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize

HOW LONG DOES A SHORT STORY TAKE TO WRITE?

Alice Munro has thrown out almost everything she wrote between the ages of about 25-35, considering it not good enough. She was plagued by writing anxiety. After she took pressure off herself and opened a bookstore with her first husband, that’s when the creative well was able to open up.

She continued to discard stories she wasn’t happy with and hasn’t regretted it. (Other short story writers echo this sentiment. Even for the best of writers, it is very common to write far more short stories than are seen by the public.)

Dance of the Happy Shades (Munro’s first short story collection) was written over the course of 15 years. There was a small gap in her output after “Friend of My Youth”, January 1990, which was followed by “Carried Away”, October 1991. (She spent three months in Scotland that year.) Other than that, she published frequently as soon as she started to get noticed (due to publication in The New Yorker). She had a first refusal contract with The New Yorker.

More typically, though, it would take about a month to write a short story. While writing, she keeps the “door” closed (she doesn’t show drafts to anyone). She didn’t actually have a room of her own, writing at a small desk under a window in the living room which looked out onto the driveway of her house.

HOW LONG ARE ALICE MUNRO SHORT STORIES?

Stories became longer over time. Early stories are typically ten pages, but later ones can run to more than seventy.

AVOIDING APHORISM

Without using the term ‘aphorism‘, Munro seems to be saying what British author Zadie Smith said later about wishing to avoid aphoristic writing:

I want my stories to be something about life that causes people not to say “Oh, isn’t that the truth,” but to feel some kind of reward from the writing.

Alice Munro, 1994

LITERARY INFLUENCES

I chose the writers who seemed to me to have the truest voices and the most reliable skills and who gave me as a reader the most lively and constant pleasure.

Alice Munro, in a 1994 speech

I learned very early to disguise everything, and perhaps the escape into stories was necessary.

Alice Munro

L.M. MONTGOMERY

Being a Canadian girl, she read Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery, though she actually preferred the lesser-known Emily of New Moon.

Munro also read classics such as the Bronte sisters.

CHARLES DICKENS

As a child she read A Child’s History of England by Charles Dickens (probably the one illustrated by F.H. Townsend) and remembers the violent bits e.g. the beheadings. Back then, adventure stories did not star women and girls. Young Alice her had her own workaround: She re-visioned them with herself as the heroine. Also, she didn’t want to be beheaded, so she changed the endings as well.

SMALL TOWN WRITERS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH

Alice Munro is a proud writer of small town life. She doesn’t consider it lesser at all. She credits Southern writers who came before for giving her the confidence to consider small town lives worthy of consideration: Eudora Welty, Katherine Anne Porter, Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers.

These authors demonstrated an ability to turn an ordinary place one might simply drive through into a real place populated with very real-seeming people.

KATHERINE MANSFIELD

New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield was a leader in the Modernist movement and is one of Alice Munro’s influences. For example, Munro utilises the Modernest, Mansfield-esque technique of opening in medias res with characters arriving in statu nascendi (without backstory).

After supper my father says, “Want to go down and see if the Lake’s still there?”

opening line to “Walker Brothers Cowboy” by Alice Munro

When dear old Mrs. Hay went back to town after staying with the Burnells she sent the children a doll’s house.

opening line to “The Doll’s House” by Katherine Mansfield

THE INFLUENCE OF CHEKHOV

Anton Chekhov is a big influence on many great modern authors (including Mansfield, who even plagiarised him). It was Chekhov who gave Munro the confidence to write about “ordinary life and ordinary people”.

Alice Munro is routinely spoken of in the same breath as Anton Chekov. She resembles the Russian master in a number of ways. She is fascinated with the failings of love and work and has an obsession with time. There is the same penetrating psychological insight; the events played out in a minor key; the small town settings. In Munro’s fictional universe, as in Chekhov’s, plot is of secondary importance: all is based on the epiphanic moment, the sudden enlightenment, the concise, subtle, revelatory detail. Another significant feature of Munro’s is the (typically Canadian) connection to the land, to what Margaret Atwood has called a ‘harsh and vast geography.’ Munro is attuned to the shifts and colours of the natural world, to life lived with the wilderness. Her skill at describing the constituency of the environment is equal to her ability to get below the surface of the lives of her characters.

Garan Holocombe’s critical analysis of Munro for the British Council of Literature

Munro has been compared to Chekhov and Tolstoy, but I think her writing is slightly less philosophical and more titillating than is theirs – and better for solitary twilight indulging.

a consumer review of Selected Stories

Like Thomas Hardy and William Faulkner, Munro restricts her canvas to specific geographies, but this does not limit the themes. In fact, this technique allows her to broaden and deepen them. A single town can throw up plots which allow writers to explore themes around coming-of-age, romance and sex, family relationships, social inequalities, the lives of (frustrated) artists.

Overall, Munro has shared in interview her favourite short story writers:

- Eudora Welty

- John Cheever

- Elizabeth Spencer

- Edna O’Brien

- John Updike

- Katherine Ann Porter

- Hannah Green

- Maeve Brennan

- Vladimir Nabokov

- Mary Lavin

- Frank O’Connor

- Mavis Gallant

- Flannery O’Connor

- Grace Paley

- Elizabeth Cullinan

- William Maxwell

Alice Munro’s favourite Canadian authors:

(Noted and noteworthy, though entirely typical of the 20th century: the whiteness of that list. Unusual and forward-looking: The high number of woman authors in a milieu which disproportionately celebrates the voices can concerns of men.)

Alice Munro has been compared to James Joyce. Both authors make use of universal themes but lay them on a foundation of philosophy.

GENERAL NOTES ON ALICE MUNRO’S SHORT FICTION

Canada started to take its short fiction writers seriously in the 1960s, which coincides with Alice Munro’s first published collection. Canadian authors were starting to write a bit differently, with new styles, non-traditional plot structures and new themes. The literary world became very interested in Canadian Identity from the 1970s:

- Butterfly on a Rock: A Study of Themes and Images in Canadian Literature (1970)

- The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination by Northrop Frye (1971)

- Divisions on a Ground: Essays on Canadian Culture (1982)

- Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature by Margaret Atwood (1972)

- Patterns of Isolation in English Canadian Fiction by John Moss (1974)

(These works are now known as the Canadian Thematic School.) Notice that Margaret Atwood is especially interested in themes of survival. This theme extends to Canadian woman writers in general. Does it apply to Alice Munro’s women? Some commentators think yes, because before Munro’s women can achieve their goals there’s almost always some kind of suffering. (Is this not true of every interesting story?)

Alongside Alice Munro writing in the 1960s and beyond were:

- Henry Kreisel

- Norman Levine

- Anne Hébert

- Mavis Gallant

- Ethel Wilson

- Joyce Marshall

- Hugh Hood

- Hugh Garner

- Margaret Laurence

- Audrey Callahan

- Mordecai Richler

These authors all made use of typical Canadian settings and stories reflected social events of the day. Alice Munro remains the most anthologised Canadian author.

But we shouldn’t underestimate what she was up against, breaking into a patriarchal literary world. Early critics dismissed her as an inconsequential author of women’s fiction writing about issues that could only ever be of interest to women. Worse, she was dismissed as a writer who didn’t give man characters due credit for their obvious natural brilliance. The men were said to be heartless. Critics doubted her little books would sell widely. Of course, those early critics were wrong. These days, it’s quite common to hear critics say of other short story authors, “Well, they’re no Alice Munro.”

Alice Munro is mostly known as a short story writer and yet she brings as much depth, wisdom and precision to every story as most novelists bring to a lifetime of novels. To read Alice Munro is to learn something every time that you never thought of before.

Judges’ comments when she won the Man Booker International Prize in 2009

COMPLEXITY

Munro’s stories have grown more complex as she has grown older. Later stories are sometimes a more complex take on an earlier one.

COHERENCE

Munro’s stories don’t cohere in the same way as chapters in a novel but together they form a unified work of art. Short stories may do a better job of highlighting certain aspects of her work than novels would have.

Something from page three will come and hit you on page thirty, but you had not registered the matter when you first read page three.

New Yorker fiction editor Deborah Treisman

By the way, this writing technique is known as delayed decoding, meaning a detail isn’t meaningful until you look back at it. The best writers are expert at this, and short story specialists are especially good at it.

- Munro reveals essential truths about ourselves in an unsentimental, yet deeply humane way.

- Missed opportunities and lies are two themes that Munro approaches from many angles.

- Consider Munro’s beginnings and endings as of a piece — the beginning will foreordain the ending, meaning once you go back and re-read the beginning, you can now see exactly where the story was going and that every single thing mentioned leads us towards the end.

- Munro enjoys experimenting with the gothic.

- Munro has said she sees stories architecturally, as a house whose various rooms one can roam in and out of, forgoing any prescribed order.

- Munro has said that she admires writers of the American South, such as Eudora Welty and Carson McCullers.

- Munro writes with black humour.

- Julian Barnes states that Munro’s short stories ‘have the density and reach of other people’s novels’.

- Some of her stories are unusually longer than typical short stories.

- Munro stories show an interest in love and the often hidden intricacies of marriage.

- A theme is often love, or perhaps romantic notions masquerading as love.

- The complications and cruelties of age and time are other themes that Munro re-visits.

- As she matured as a writer, Munro became more experimental rather than less so.

She reminds us that love and marriage never become unimportant as stories—that they remain the very shapers of life, rightly or wrongly. She does not overtly judge—especially human cruelty—but allows human encounters to speak for themselves. She honors mysteriousness and is a neutral beholder before the unpredictable. Her genius is in the strange detail that resurfaces, but it is also in the largeness of vision being brought to bear (and press on) a smaller genre or form that has few such wide-seeing practitioners. She is a short-story writer who is looking over and past every ostensible boundary, and has thus reshaped an idea of narrative brevity and reimagined what a story can do.

Lorrie Moore, The New Yorker

The particular and careful ways Munro’s themes are laid into her narrative trajectories cause them to sneak up upon the reader

Lorrie Moore, Living in the Story: Fictional Reality in the Stories of Alice Munro, Charles E. May

There are certain things she almost always does (once past her earliest works): begin with a story that isn’t the real story and doesn’t even really illuminate the real story but is just as interesting as the real story; tell us how different characters are approaching a “shared” experience; show how aware and critical many rural Canadians are of deviations from their cultural norms; hint at what deviant secrets are kept by same; display the variety of ways that rural Canadian women have asserted their needs and desires; conclude almost arbitrarily.

from a consumer review of Selected Stories

There is plenty of multivalent detail throughout Munro’s fiction, meaning a particular detail can be read at a literal as well as symbolic level. This is perhaps why Munro’s details seem, at first glance, ‘strange’.

Even when you are surprised by a shift in a character’s thoughts, it seems completely organic. We all make those kinds of transitions in our thinking processes, even though they don’t point to an end the way a story does.

An Appreciation Of Alice Munro

Munro should be honored not just for her immense talent, but for the stereotype-busting subject matter she chooses. Her writing is often dark, gruesome and unabashedly “unfeminine” in the traditional sense, refusing to shy away from the grit and small tragedies of human existence.

Ms. Magazine

Alice Munro has a gift for exposing the strange customs of our realm—the realm I live in & have formed my identity and relationships in- without direct commentary but in a way that as reader, I stand back somewhat aghast at this odd, normalized world.

The London Literary Salon

I am always a bit astonished by how casually Munro uses her artistry to illuminate the everyday—the superficially banal experience of life in small-town Canada in the middle years of the 20th ct. (I know, spoken like an arrogant urbanite)—while gesturing towards the open veins of unspoken truths & sudden transcendence. One minute you are reading about a silver fox farm used to produce skins and next, you are examining the quiet mental violence of gender education. This is, for me, the most succinct response to the subtle art of the short story.

The London Literary Salon

DOPPELGEDANKEN

The Germans must have a term for it. Doppelgedanken, perhaps: the sensation, when reading, that your own mind is giving birth to the words as they appear on the page. Such is the ego that in these rare instances you wonder, “How could the author have known what I was thinking?” Of course, what has happened isn’t this at all, though it’s no less astonishing. Rather, you’ve been drawn so deftly into another world that you’re breathing with someone else’s rhythms, seeing someone else’s visions as your own.

“One of the pleasures of reading Alice Munro derives from her ability to impart this sensation. It’s the sort of gift that requires enormous modesty on the part of the writer, who must shun pyrotechnics for something less flashy: an empathy so pitch-perfect as to be nearly undetectable. But it’s most arresting in the hands of a writer who isn’t too modest — one possessed of a fearless, at times, fearsome, ambition.

from a NYT review of Alice Munro’s work written by Leah Hager Cohen. Published: November 27, 2009

THE SETTINGS OF ALICE MUNRO SHORT STORIES

Alice Munro’s favourite size place is the small town: “the small town is like a stage for human lives.”

WHEN ARE ALICE MUNRO STORIES SET?

Born in 1931 herself, Munro’s stories begin during the era of the Great Depression in Dance of the Happy Shades (1968). The stories in that first collection span many years, as it took Munro many years to write them.

Individual stories can span many decades of a woman’s life across the 20th century, and tend to, sometimes encompassing the lives of mothers and grandmother figures as well as contemporary experiences.

WHERE ARE ALICE MUNRO STORIES SET?

Munro’s setting is sometimes said to be “quasi-regional” or “quasi rural”. The term “quasi-regional” refers to a setting or context that has characteristics of a specific region or locality but is not strictly limited to it. It implies that while the stories in Munro’s Dance of the Happy Shades are primarily set in a particular geographical location (southwestern Ontario and the Pacific coast), they also touch upon broader themes and experiences that extend beyond the boundaries of that specific region. The term “quasi-regional” suggests that the stories capture the essence of a specific locale while also addressing universal themes and experiences that can resonate with readers from different backgrounds.

Southwestern Ontario is sometimes known as Alice Munro Country, but this doesn’t just apply to the geographical location. When people say this, they’re talking about a milieu, a New World, a magical place were readers can step into a story and feel as if we are really there.

Héliane Ventura has said that there are three emblematic sites found across Alice Munro’s work:

- A snow-bound landscape

- A sand-covered beach

- A star-lit swamp

Others, e.g. Sabrina Francesconi, have added the domestic sphere to that list of sematic spaces, notably the linoleum of the kitchens.

- In “Walker Brothers Cowboy“, linoleum indicates the unheimlich nature of Nora Cronin’s home and the uncomfortable reality that, had the narrator’s father married this woman instead, she wouldn’t exist.

- In “Lives of Girls and Women”, “People’s lives, in Jubilee as elsewhere, were dull, simple, amazing and unfathomable—like deep caves paved with kitchen linoleum.”

CANADA

It means something to me that no other country can – no matter how important historically that other country may be, how ‘beautiful,’ how lively and interesting. I am intoxicated by this particular landscape. I am at home with the brick houses, the falling-down barns, the trailer parks, burdensome old churches, Wal-Mart and Canadian Tire. I speak the language.

Alice Munro

- Munro often portrays the Canadian landscape as a significant backdrop in her stories. She vividly describes the rural settings, small towns, and natural surroundings, capturing the essence of the Canadian environment.

- Isolation and Loneliness: Munro’s characters often experience isolation and loneliness, a reflection of the vastness and remoteness of certain Canadian landscapes. This theme resonates with the idea of the individual’s struggle to find connection and belonging within a vast and diverse country.

THE SMALL TOWNS OF ALICE MUNRO’S IMAGINATION

The small town of Jubilee, illuminated most vividly in The Lives of Girls and Women (1971), is not a real place, but rather a fictional small town in southern rural Ontario with similarities to Wingham, where Munro grew up, and to Clinton, where Alice Munro settled with her second husband.

In Munro’s later collections, Who Do You Think You Are? and Open Secrets, this autobiographical town is recapitulated as the small towns of Hanratty (in Who Do You Think You Are?) and Carstairs (in Open Secrets).

ARE ALICE MUNRO’S CHARACTERS BASED ON REAL PEOPLE?

Munro has had a bit of trouble with the residents of Wingham, North Huron. Some feel she is writing about them, and not representing them very nicely. They do not appreciate Munro’s grotesque treatment, her disenchantment and sarcastic style. But Munro herself has said on record that she does not write documentary, and readers should not read with a documentary gaze.

The colophon to a paperback edition of Lives of Girls and Women says this:

This novel is autobiographical in form but not in fact. My family, neighbours and friends did not serve as models.

A.M.

(Also interesting: Munro considers Lives of Girls and Women a novel rather than as a collection of interlinked short stories.)

Sometimes, even critics mistake Munro’s fiction for thinly veiled autobiography. (This is a problem woman writers typically face, as described in How To Suppress Women’s Writing by Joanna Russ. “She wrote it but… it’s not real fiction. It’s autobiography.”)

MUNRO AS REGIONALIST WRITER

Alice Munro is frequently called a regionalist writer because of her attention to details. Regionalism is a largely American term which refers to texts that concentrate heavily on specific, unique features of a certain region including dialect, customs, tradition, topography, history, and characters.

The “entangled bush”, the “flat fields”, the “dusty roads”, the “red-brick unpainted houses” with the “bare yards” are recurring touches that Munro’s readers look for when starting a new story. This location is often selected for the profound attraction and connection the writer feels.

Clearly, small-town Ontario is more a social community strictly embedded in the territory people live in than a mere physical site.

Negotiation of Naming in Alice Munro’s “Meneseteung” by Sabrina Francesconi

[Munro’s stories] are translations into the next-door language of fiction of all those documentary details, those dazzling textures and surface, of remembered experiences.

Catherine Sheldrick Ross, Alice Munro: A Double Life, 1992

[Munro’s] magic lies in the concoction of the sentences—strings of simple words together that produce visceral response. These sentences aren’t ubiquitous, rather, they are put strategically in between pages and shock you out of the blue. And this combination of laid back, introverted sentences interspersed with jolting emotional outbursts is what makes her works stand out.

a consumer reviewer

The Maitland River is important, though Munro tends to avoid calling it that. It might be called the Wawanash River or Meneseteung. She doesn’t even name it in this snippet from a 1974 interview:

I am still partly convinced that this river—not even the whole river but this stretch of it—will provide whatever myths you want, whatever adventures. I name the plants, I name the fish, and every name seems to me triumphant, every leaf and quick fish remarkably valuable.

“Everything Here is Touchable and Mysterious”, Weekend Magazine , Toronto Star, 5 November 1974.

The ‘real worlds’ of Munro’s stories have settings dotted around Canada, focusing on Southwestern Ontario, where Munro has spent the majority of her life. During her first married she lived in West Vancouver and Victoria, so she knows the other side of Canada as well.

Munro’s sense of irony is invariably directed at herself more than at her characters. She has always regarded herself as an anachronism: an old-style writer, writing about a rural world she once knew, which has been transformed. Except that, although society has changed, human nature hasn’t, and this is why Munro’s understanding of life is so compelling.

Irish Times

WHAT’S UNDER THE LINOLEUM?

A Katherine Mansfield scholar talks about ‘the snail under the leaf‘ of Mansfield’s settings. Everything seems fine on the surface, but bend down to lift a leaf (examine the details) and you’ll find something surprising, slightly repulsive, grotesque and shocking, something you were never supposed to see. (No shade to snails, who are blameless in this.)

Munro scholars have a similar analogy, but for Munro they talk about what’s under the linoleum:

The narrator wants readers to see what lies hidden beyond the thin layer of linoleum — to use one of Munro’s recurring domestic metaphors. She wants them to go beyond covers of respectability, and look for the perhaps threatening unheimlich [uncanny]. Not in order to have reasons for condemnation, but in order to appreciate a more vivid and vibrant, less opaque and aseptic character.

Negotiation of Naming in Alice Munro’s “Meneseteung” by Sabrina Francesconi

This linoleum comparison comes from Alice Munro herself, via the narrator of Lives of Girls and Women:

People’s lives, in Jubilee as elsewhere, were dull, simple, amazing and unfathomable—deep caves paved with kitchen linoleum

Lives of Girls and Women

For Munro, linoleum is a symbol of domesticity and the working-class life. Linoleum is often described in detail, along with other sensory details (especially smell and touch). For example, in “The Time Of Death”, Patricia kicks at a crust of porridge that has dried on the linoleum. This starts the cleaning frenzy which leads to the accident. In “Walker Brothers Cowboy“, the linoleum as described by the young narrator creates a unheimlich (unhomeliness).

Linoleum appears in so many of Munro’s short stories that this flooring material creates sense of continuity and intratextuality across Munro’s collections, from Dance of the Happy Shades through to Dear Life.

JUBILEE

It has occurred to me that every small town I have ever read about since Munro has been Jubilee. no other place, fictional or not, has such a hold on me. I know the singular road into town, the fox farm and it’s surrounding field, the dance hall, the cool dark hardwood floors of the schoolhouse. […] Munro is my queen, my first love, my litmus test.

from a consumer review

SOCIAL REALISM

Alice Munro feels the role of her stories is to ‘stay above reality’. She advises short story authors to “pursue their own visions of reality to the deepest — and possibly the darkest — places in their imagination”.

Of course, when artists stay ‘above reality’, they are now dealing in the genre of surrealism or hyper-realism or some other kind of hyper- or super- genre.

Munro is our greatest and most subtle surrealist. The plainest of surfaces ignite with the fugitive erotic undertow. After sex, even a readymade supermarket lemon cake can feel like a miracle.

Allan Gurganus

Some commentators say Alice Munro’s work is ‘documentary’, whereas others go so far as to say it is magical realism. Either way, Alice Munro is heightening realism to a point where the ‘truth’ or a situation (insofar as the truth can be accessed) is self-evident to readers. This applies to both documentary and the hyper- genres. In any case, avoid thinking of ‘realist’ and the ‘fantasy’ genres as belonging to two distinct groups. In everyday life, the two states of mind co-exist. A fantasy imagination illuminates the truth of reality.

Social realism is a literary and artistic movement that aims to depict the realities of society, particularly the struggles and inequalities faced by marginalized individuals or groups. See Munro’s Dance of the Happy Shades collection for excellent examples of social realism. These short stories reflect Munro’s concern for society and portray the societal prejudices faced by women in Canada across early decades of the 20th century (especially the 1940s and 50s).

Munro was part of a larger literary move towards depicting the lives of marginalised people in a time of economic inequality. (Dickens and Thackeray started this trend over in Britain.)

Munro’s own childhood was marked by poverty, parental illness (in which Munro was the young caregiver) and social inequality (in which misogyny affected Munro’s generation of women).

However, Alice Munro doesn’t simply capture “everyday life” of a certain Canadian milieu, but delves deep into characters’ psychology.

IS MUNRO’S WORK MAGICAL REALISM?

The landscape of a Munro short story has been described as a consanguinity between the fictional and the real. (Meaning they both come from a common ancestor.)

The setting of the real is portrayed as affectively meaningless to us. (The fictional is as important, on a psychological level, as the imagined, or the hoped for.)

There’s been a lot of critical interest around the realism of her work, with some people making reference to magical realism.

Munro often creates a world that has all the illusion of external reality, but she pulls the reader deeper and deeper into what becomes a hallucinatory inner world which may include mystery, secrecy, and deception.

Munro deemphasizes physical action in favor of the mind in action. In her stories, the central action is almost always the act of perception itself; other actions, what we might normally consider to be the plot, are subsumed or transformed to this end.

David Crouse, “Honest Tricks: Surrogate Authors in Alice Munro’s Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage.” In Critical Insights: Alice Munro, ed. Charles E. May. Salem Press, 2013

DESTINY AND FATE

In many of Munro’s stories the willing of a destiny is overtaken by a fatality that is unnervingly spectacular. Characters are driven by something they cannot resist because they are certain they are a part of it. Munro explores fatality in many different ways across many of her stories.

TIME

A common Munro device is to begin in the now and hurtle back to the then.

Much has been said about how Alice Munro can write a novel in the space of a short story.

Alice Munro can move characters through time in a way that no other writer can. You are not aware that time is passing, only that it has passed—in this, the reader resembles the characters, who also find that time has passed and that their lives have been changed, without their quite understanding how, when, and why. This rare ability partly explains why her short stories have the density and reach of other people’s novels. I have sometimes tried to work out how she does it but never succeeded, and I am happy in this failure, because no one else can—or should be allowed to—write like the great Alice Munro.

Julian Barnes, The New Yorker

Munro is more experimental than she’s given credit for—her leaps in time are jarring and amazing. Especially in the stories that are connected by character and place, a collage-like effect begins to take hold, and you feel that Munro is filling in the details of a much larger canvas than it initially appeared.

from a consumer review of Selected Stories

NAMES OF PLACES AND PEOPLE

In Alice Munro’s stories, names are much more than labels with the function of positioning the named item—be it a person, a place, or else on a geographical map or on a civic archive. Names are, in fact, sites of negotiation for identity, and historical and cultural issues. They are never accepted as definite products, but questioned as performative and open textual units.

Sabrina Francesconi, Journal of the Short Story in English, Autumn 2010, Negotiation of Naming in Alice Munro’s “Meneseteung”

VOICE

The criticisms for her work primarily focus on a lack of versatility in plot or voice, though I find this part of why returning to her work is always so comforting. While it is true that a vast majority of her stories have the same formula of ‘woman leaving one position of life, be it a relationship, job, living location, religions conviction, eventual death of oneself or a loved one, etc., and begins to forge a new one by critiquing the mistakes of the former’, Munro is able to still keep each story unique, yet familiar in a sense that makes it seem applicable to any reader in some way, shape or form. The voice is often level from story to story, yet, especially with this selected stories collection, she manages to keep the delivery fresh by attempting different story telling devices.

a consumer review of Selected Stories

LANGUAGE USE

Beginner writers are frequently advised to make sparing use of adjectives (advice which can be taken too far and too literally). Alice Munro’s stories offer an excellent case study in adjectives deployed well: Adjectives tend to be unexpected, and deepen a sentence as a result.

Narration can be blunt, harsh and sarcastic. This voice on steroids is frequently utilised by Margaret Atwood, and can also be seen in authors such as:

- Thomas Chandler Haliburton

- William Alexander Thomson

- Stephen P. H. Butler Leacock (Munro’s attitude towards rural Ontario compares to Leacock’s attitude towards smalltown, provincial Ontario cf. Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, 1912.)

- William Ormond Mitchell

- Stuart Ross

- Robert Paul Kroetsch

DIALOGUE

Munro renders dialogue in the colloquial style found around Ontario, and her characters switch register to indicate economic class and so on. Fictional dialogue is never exactly the language of the people, but can only ever be an approximation. Munro’s dialogue conveys a matter-of-factness in keeping with the everyday settings of the stories.

PARADOX

Look for paradox in the work of Alice Munro at all levels, from the structural to the sentence level. Paradox illuminates oppositions which confront us in our everyday lives.

CHARACTERISATION

Writing about her mother is the central topic which has consumed Alice Munro across her career: “If I just relax, that’s what will come up.” After living with severe Parkinson’s disease for many years, Anne Clarke Chamney Laidlaw died in 1959.

Many writers will echo this practice: Alice Munro knows a lot more about her characters than what appears on the page. Audiences see a snapshots of her characters’ lives, but they feel rounded because Munro has already nutted out a whole life in her head, including what clothes they’d choose, what they were like at school, what happened before and what will happen after the part of their lives I’m dealing with.”

That said, Munro does utilise ‘flat characters’. (It’s impossible to populate a short story with characters and flesh them all out.) Examples of flat characterisation:

- Uncle Benny (from The Flats Road)

- Flo (from The Beggar Maid)

- Jack (a good name for a flat character)

- George

Examples of significantly rounded characters:

- Del Jordan

- Rose

- Prue

- Frances

- Louisa

- Maureen

- Gail

- Marietta

- Lydia

See also: Three Ways of Looking at Character

Part of the complexity of Munro’s rounded chararcters derives from the sense that characters have complex motivations and unconscious desires. This is difficult to portray on the page, but Munro manages it beautifully. Oftentimes, characters don’t react as you might expect them to. For example, Del Jordan’s response to the manfriend of her mother’s boarder in the Lives of Girls and Women collection or, similarly, the complex emotions of the new, young housemaid in “Sunday Afternoon“.

Intense emotions and desires can lead to unforeseen directions in life e.g. in “How I Met My Husband“, and also in The Love of a Good Woman collection:

“In these eight stories, a master of the form extends and magnifies her great themes–the vagaries of love, the passion that leads down unexpected paths, the chaos hovering just under the surface of things, and the strange, often comical desires of the human heart.”, “The questions, discussion topics, and author biography that follow are intended to enhance your group’s reading of Alice Munro’s collection The Love of a Good Woman.”

Sara Freedman & T. Louise M. Kidder 1990

Rounded characters all show the capacity to change. This change happens slowly and incrementally, as it does in real life. (People do not change quickly.)

In contrast, flat characters do not change. They remain unchanged. Events happen to the rounded character, but the flat ones remain untouched.

Alice Munro knowingly creates characters who make decisions readers are unlikely to ‘agree with’ or ‘approve of’. Characters behave in very human ways, not necessarily in morally upright ways. We empathise adulterers, fakers, liars, absconders. We are invited to pass judgement and then retract it as we come to the realisation that no decision is made in a vacuum, and everyone has their reasons for doing what they do.

INDIRECT AND DIRECT CHARACTERSIATION

Some commentators think in terms of ‘indirect’ vs ‘direct’ modes of fictional characterisation.

Indirect characterisation

When an author reveals a character’s traits through actions, thoughts, speech, etc., instead of saying it outright.

Direct characterisation

When an author explains character details directly to the reader, indirect characterization shares details through a character’s actions, dialogue, or internal monologue.

Or, showing versus telling. Alice Munro utilises both forms.

Whichever method she uses, Munro reveals character via telling details:

- character names

- their clothing

- their houses and living environment

- dialogue

- their actions

CHARACTERS ARE SUBORDINATED TO MOOD

Characters and events don’t really matter in her stories, she says, for they are subordinated to an overall “climate” or “mood.” In Munro’s best work, the hidden story of emotion and secret life, communicated by atmosphere and tone, is always about something more enigmatic and unspeakable than the story generated by characters and what happens next. Her greatest stories simply do not communicate as novels do.

Charles E. May

The Construction of Characters’ Identities by Interweaving Images of Past and Present

“She constructs her characters’ identities by interweaving images of past and present in multi-layered narratives of individual memory.”, “Munro’s narratives are characteristically intense and condensed character studies, intimate and psychological portraits of women and men, frequently embedded in the dynamic clash between individualism (e.g. figures of outsiders) and community (family, small town setting, etc.).”

Jędrzej Burszta 2016

Women Maintaining Various Selves in the Face of Men’s Control

“Also in Bronwen Wallace’s essay, the focus in on the themes of gender and identity in Munro’s works, including the mother-daughter relationship and the contradictory nature of maternal feelings, women’s bodies, male-female relationships in which women maintain various selves in the face of men’s struggle to control or deny them.

“With the advent of postmodernism attempts to explain apparently universal gender inequalities of power were abandoned and the focus returned to gender as an attribute of individuals constructed through cultural practice.”, “This can be seen as part of the cultural turn within sociology whereby culture displaced society and the economy as a focus of theoretical concern.” (C. Nicolaescu 2014)

Two collections of stories: Lives of Girls and Women and The Progress of Love to be reflective of a writing form defined by French feminist critics as l’ecriture feminine.”, “Inherent in Munro’s thematic interest in the personal construction of identity is an awareness of the significant role played by gender in establishing who we are and how we see the world.”

C. Nicolaescu 2014

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO WRITE ABOUT ORDINARY LIVES?

It’s often said that Alice Munro writes about ‘ordinary lives’, for example:

The real delight of reading Munro—slowly and deliberately—is this: one awakens to the beautiful and perverse in the very ordinary people living among us.

The London Literary Salon

The second-rate writers, the writers manqués, the professional-commercial writers, find it impossible to write about ordinary people in ordinary situations, living ordinary lives, and make the people, their lives and their situations not only plausible and pleasurable but artistically alive. Hence their reliance on the grotesque, the far-out theme, the “different” or snob character, and the exotic or non-existent locale. The literary artist, on the other hand, uses people we all know, situations which are familiar to us and places we know or remember.

Hugh Garner, in the foreword of an edition of Dance of the Happy Shades

And here’s what Munro says about that:

Everyone is extraordinary to themselves. Nurses have about the most dramatic life I can think of… I never consider these people ordinary. But then I never meet anybody that I consider ordinary.

Alice Munro on CBC

A FINE DOUBLE AWARENESS

Munro explores juxtaposed worlds in her fiction…she uses her characters to probe the relationships between psychological spaces and the outside world. Her female characters all have a fine double awareness of community values and of what else goes on outside those limits. They are fascinated by dark holes and unscripted spaces with their scandalous discreditable stories of transgression and desire. The romantic fantasies, the glimpses of interior lives and the rumours and gossip these engender are part of this recognition of other worlds.

The London Literary Salon

Most of Munro’s main characters are women, but not all of them. “Face” (2008) is from the point of view of a young boy.

Claire Thurlow

- Munro has the ability to recreate the mundanities of ordinary lives, but also to gently peel away the layers and reveal the raw emotions submerged beneath.

- There is great poignancy in Munro’s description of individuals who don’t fit in and obvious pleasure in her revelations of their small triumphs.

- Alice Munro writes many stories about women in mid-life, caught between memory and reality. Throughout the narrative they reassess and reflect.

- But occasionally she writes a child character, e.g. “Trespasses”, in which Lauren is a ten-year-old girl.

- For Munro’s characters, to imagine something is to understand it.

- Munro’s work is interested in men with menacing water, especially hoses. (Is this sexual?)

- Munro’s women are perceptive guessers, quiet visionaries, fortuitous survivors.

- Young woman characters pay the price when they do not conform to societal constraints.

Munro is in quest of a body experienced by women as subject of their desires not as object of men’s desires and of the words and literary forms appropriate to this body.

Barbara Godard in “Heirs of the Living Body: Alice Munro and the Question of a Female Aesthetic”, 1984

FAMILY STRUCTURE

Families are usually complicated in Alice Munro stories. Families aren’t nuclear; marriages aren’t lifelong/faithful. In later stories, the wider network is populated with LGBT characters. This is, of course, like life.

MOTHERS

Alice Munro’s mothers have been likened to clowns: Mothers and Other Clowns: The Stories of Alice Munro by Magdalene Redekop (a feminist work).

“Engaging with the distinct significance of this survival for women, Munro’s late fiction revisits the figure of the self-sacrificing mother and the woman who refuses to play a sacrificial role and helps us to describe the gendered contours of a posthumanist ontology.”, “This chapter examines the motif of survival in a pair of stories by Alice Munro that concern women who survive violent men and in a series of stories that involve parents who are abandoned by their children.” (Naomi Morgenstern 2018)

“Munro’s late fiction revisits the figure of the self-sacrificing mother and the woman who refuses to play a sacrificial role and helps us to describe the gendered contours of a posthumanist ontology.” (Naomi Morgenstern 2018)

The Contradictory Nature of Maternal Feelings

“Also in Bronwen Wallace’s essay, the focus in on the themes of gender and identity in Munro’s works, including the mother-daughter relationship and the contradictory nature of maternal feelings, women’s bodies, male-female relationships in which women maintain various selves in the face of men’s struggle to control or deny them. With the advent of postmodernism attempts to explain apparently universal gender inequalities of power were abandoned and the focus returned to gender as an attribute of individuals constructed through cultural practice.”, “For example, Loma Irving refers in her articles to several of Munro’s stories in which the mother-daughter relationship is pivotal.” (C. Nicolaescu 2014)

Is Alice Munro feminist?

Alice Munro is a smart, thinking woman who has lived in the world and she definitely understands how the gender hierarchy works. This is evident from her stories, but also evident from what she says about her life.

As one example, she briefly tried teaching. As it happens, she didn’t enjoy it, and her teaching career didn’t last long. Why did she despise it? The creative writing class was heavily male dominated, and the one young woman participant “hardly got to speak”. Munro considered the writing of the students (overwhelmingly young men) “incomprehensible and trite; they seemed intolerant of anything else”.

It seems to me she’d had a gutsful of reading and hearing nothing but the voices of men by the time she was teaching at Toronto’s York University back in 1973. And because she was around academia at that time, she was clearly exposed to feminist activism in the air. She lived through massive changes, and is of the generation of women who can mark a fairly distinct line between the lives they expected as girls, and the lives they were allowed to live as adult women.

Like Chekhov, Alice Munro never sets out to make a political point. She isn’t sexist, she has no axe to grind. She’s simply bearing witness to the human experience, reporting from the front lines. Yet she is making a political point, one that’s radical because it’s so enormous and so unsettling. The point is that girls and women, even those who lead narrow and constricted lives, those who wield no influence, who have a limited experience in the world, are just as significant and important as boys and men, those who take drugs, ride across the border, drift down the river, or hunt whales. Women’s lives, too, are driven by the great forces that drive all important experience. As it turns out, all those forces are internal: rage, love, jealousy, spite, grief. These are the things that make our lives so wild and dramatic, whether the backdrops are harpoons or swing sets. The great experiences can be set anywhere: a dentist’s office, a neighbor’s living room, a country road at night. It’s those propulsive, breathtaking, suffocating forces inside us that make those moments so vivid and shocking, it’s what’s inside us that cracks the landscape open, shocking and illuminating like a streak of lightning. She showed us that, Alice Munro.

Roxana Robinson

UNSENTIMENTAL WORLD VIEWS

Characters are lacking in sentimentality. Alice Munro has said in an interview regarding the death of her own daughter, soon after giving birth, that she went home and barely talked about it with her first husband because they were not a sentimental couple. This reminds me of my grandparents, who were probably the same after their own stillbirth experience in the late 1950s.

All of Munro’s stories include death, either an actual death or characters dealing with the reality that everyone must eventually die.

- “The Time of Death“: a child dies in a tragic accident

- There are two well-known suicides in the town of Jubilee in The Lives of Girls and Women.

- In “Who Do You Think You Are?” Rose’s father is mortally ill

- “Simon’s Luck”: Simon is mortally ill

- Ralph Gillespie dies unexpectedly

- Flo goes to an old people’s home

- etc.

FANTASIES BUT NOT FANTASISTS

It is reality that awakens possibilities, and nothing would be more perverse than to deny it.

Robert Musil, The Man without Qualities

There are tales featuring out-and-out fantasists, like the short story “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and the film My Summer of Love, but Alice Munro’s characters are not fantasists. Instead, they are firmly reality based on the Continuum Of Imaginative Powers. Characters use imagination to explore alternate realities, to cope with grief and other uncomfortable emotions. When awful things happen in life, they retreat into their imaginative inner lives. This sustains them.

Munro’s characters often grapple with their memories, which can be both a source of comfort and a cause of distress. She explores how memory shapes identity and how it can be both reliable and unreliable.

The difficulty of authentic and complete reconstructions of events in Munro’s fiction is not, on the whole, a problem of history, and much less of an exuberant postmodern sensibility, but of a general conviction that life is comprised of “disconnected realities. […]

Though Munro’s characters are grounded in reality, characters have fallible memories. When Munro takes the reader along on remembrances of the past, at no point are we encouraged to believe every single word. (Wrong) memory can influence someone’s present as much as the past reality.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

The secret of Alice Munro’s short stories is that she is able to suggest universal, unspoken human desires—preferring meaningful fantasy to the insignificant actual, aesthetic disengagement to physical entanglement, the memoried past to the simple present—by describing what seems to be ordinary everyday reality. Her stories are complex and powerful not so much because of what happens in them, but because of what cannot happen except in the mysterious human imagination.

Charles E. May

Memory, however, is fallible. It is incomplete. Munro does an excellent job of recreating how memory really works. Perhaps only older readers will appreciate this particular aspect of her stories; instead of remembering the ‘plots’ of past events, even big events, we tend to be left with resonant imagery. We forget people’s names, even if they were important to us. Minor characters become larger in hindsight. Significant characters can seem almost fictional in hindsight.

In creating a sense of imperfect memory, Alice Munro makes much use of a technique I’ve seen described as ‘side shadowing‘. It’s especially useful to the short story writer because the story seems so much more expansive. Side-shadowing is used in various ways, and Munro has numerous reasons for using it.

Here’s how Ulrica Skagert puts it:

The phenomenon of possibility permeates Munro’s stories. An investigation of this phenomenon shows a curious paradox between possibility and necessity.

It’s not just fallible human memory which toys with the ‘reality’ presented to readers. Characters tend to have the following psychological and moral shortcomings:

Munro’s fiction most often suggests that a determinate set of events lies behind the text, but that the conflicting self-justifications of her characters undermine narrative certainty. Familiar motives and shortcomings—the everyday dishonesty fostered by self-interest; the inclination to suppress what is ugly and disturbing; and the failure to exhibit a systematic sense of responsibility in our dealings with others—animate the accounts of Munro’s characters.

‘Who Was It If It Wasn’t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis

The Use of Multi-Layered Narratives of Individual Memory

“She constructs her characters’ identities by interweaving images of past and present in multi-layered narratives of individual memory.”, “Munro’s narratives are characteristically intense and condensed character studies, intimate and psychological portraits of women and men, frequently embedded in the dynamic clash between individualism (e.g. figures of outsiders) and community (family, small town setting, etc.).” (Jędrzej Burszta 2016)

THE INVERSE OF MELODRAMA

Munro includes details which prevent her stories from slipping into melodrama. The Irish Times describes her as a ‘coolly astute observer of the ordinary’. Alice Munro writes the opposite of melodrama. Instead, terrible and life-changing events happen alongside the mundane events, mostly. Instead, terrible and life-changing events happen alongside the mundane events, mostly. For instance, a husband dies suddenly while at the hardware store (in “Free Radicals”). Instead of the wife at home, wondering what’s happened to him, “She hadn’t had time to wonder about his being late.” Munro’s achievement is that she spins the mundane into metaphor.

[Munro is] simultaneously strange and down-to-earth, daring and straightforward.

Jane Smiley, in her foreword to Family Furnishings

VOCATIONS OF CHARACTERS

Characters are often: housewives, teachers (especially music teachers), university lecturers (philandering), carpenters and doctors (often scoundrels, despite their social standing), pharmacists—not many people have really obscure sounding jobs, but maybe no one did last century?

Piano teachers, divorced professors, country doctors, solitary widows in the country—all those small and insignificant people lead lives of enormous drama. Women lead lives of enormous drama. She has made that into fact.

Roxana Robinson, The New Yorker

EMOTIONAL LABOUR

The women are shown performing emotional labour in a way you don’t tend to find in stories written by men, even when men are creating female characters. Most men simply don’t seem to get the extent to which women are acculturated in this area. The opening paragraph of “Free Radicals” is a perfect example of this:

At first, people kept phoning, to make sure that Nita was not too depressed, not too lonely, not eating too little or drinking too much. (She had been such a diligent wine drinker that many forgot that she was now forbidden to drink at all.) She held them off, without sounding nobly grief-stricken or unnaturally cheerful or absent-minded or confused. She said that she didn’t need groceries; she was working through what she had on hand. She had enough of her prescription pills and enough stamps for her thank-you notes.

“Free Radicals”

Alice Munro famously writes about the lives of caregivers, having been a young caregiver herself to her mother, who had Parkinsons for years before she died.

ALCOHOL

If there’s drug use in her stories, it’ll be alcohol. When asked if she took drugs during the hippie era, Alice Munro replied maybe a little marijuana, but alcohol is the drug of her generation.

CHARACTER DESIRE

Munro has also talked about how women of her generation never developed their own personal desires until the hippie era hit them, and then it hit them with a force. Even at the age of 30, Alice Munro felt 18 again. Likewise, the younger versions of the women in her stories often seem quite passive. By the time these women are old ladies they’ve perhaps become a little more self-actuated, but young women are often propelled along by others, mostly men, who really did run that world. Women of Munro’s generation were expected to get married and have children. Any other kind of desire was considered unfeminine. Munro herself had exactly those desires. (Munro published her first book age 37, before her awakening. If she’d published earlier, we would’ve seen quite different work.)

SEX

I know of nobody who writes as well as Munro about ‘the hardhearted energy of sex.

John McGahern, “Heroines of Their Lives, Times Literary Supplement, 2001

What is it about sex that Munro writes about? Although the physical is important, sex is something more in her stories. It seems to have some to do with the nature of desire, but more than orgasmic desire. Sex has something to do with freedom or control. Desire is not just something you do, but something you think about and something you recall. It always seems to be more important in the past and in the future than in the present.

Charles E. May

The birth and death of erotic love, and the strange places people are led to because of it…is Munro’s timeless subject. [The] arranging of love…and the seismic upheavals of its creation and dismantling…is both a kind of pornography of life as well as the very truth of it: it is often the most pervasive and defining force in the shape of individual existence and individual fate.

Lorrie Moore, “Artship”, The NY Review of Books, 2002

For Alice Munro, desire is never just unruly and destructive. It is also expansive, creating room for experience.

Sebastian Smee, Review of Hateship. Prospect. Oct. 25, 2001

What most interests Munro about adultery is the drama of the self-divided.

Michael Ravitch, “Fiction in Review.” Oct. 2002, vol. 90, Issue 4

See also: The Divided Self (An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness) by R.D. Laing (1964)

YOUNG AND OLD TOGETHER

The cast of characters will most likely contain both young and old, and that’s aside from the narrator’s young and old self. For instance, a young woman will meet an old woman. This reminds her of her own mortality, perhaps, or the older lady from the past connects the main character’s older and younger self in a way that may not have been evident to the character herself. We are constantly reminded as readers that our age is not our identity; at some point we are young and, if we are lucky, at some point we are old.

Independence of Mind is Characters’ Only Weapon Against the Larger Forces of Coercion

Particularly in the Dance of the Happy Shades stories.

“Both coercion and Munro’s strategies of resistance remain live issues, for Canadian and non-Canadian readers alike.” (C. Masel 2014)

CHARACTERS ARE SHAPED BY THEIR CIRCUMSTANCE

In this post I explain the difference between folk psychology and studied psychology: People do not have much in the way of enduring character—how we behave in any given situation depends largely on the situation.

A difference between genre fiction and good literary fiction—in literary fiction characters behave according to their circumstance, as people in real life would. Below, a reader explains this in a review of Munro’s collection, The Love Of A Good Woman:

Loving Munro is … easy because her ethics of care and compassion for others [is] embodied by these stories, for example by Enid, the protagonist of [“The Love Of A Good Woman”]. Yet Munro refuses to paint an icon for worship: Enid can live as she does only because of her enabling circumstances, she experiences poisoned fantasies, and her goodwill is not unconditional. The same is true for other characters: each person in the book is carefully drawn as an individual shaped by histories, enmeshed in social structures that influence, constrain, oppress, enable, direct, oppose and support them in interconnected ways. They are at least partly responsible for their fortunes and failings, but Munro never victim-blames or hero-worships.

from a Goodreads reviewer

QUINTESSENTIAL THUMBNAIL CHARACTER SKETCHES

Here’s the problem with thumbnail character descriptions and why I shy away from writing them myself: By simply describing someone, we are actively encouraging the reader to fall back on stereotypes. Without existing prejudice, character sketches can’t do their job and are useless. Why does a writer give us a character’s BMI? Is it simply to paint a picture in our mind? Or are we meant to map society’s view onto characters?

Yet if writers avoid describing characters altogether, readers may fail to paint a picture. Moreover, they’ll come up with their own picture. I once wrote a short story, put it through critique. Halfway through the story I mentioned the main character’s beard. A critique partner said that I’d ‘sprung the beard’ on them. I found the imagery of that funny, but the reason they felt that way? I hadn’t started with any thumbnail sketch.

How to write character sketches without the inevitable downsides?

Well, Munro doesn’t shy away from telling us someone’s BMI and we can easily deduce where they would fall on the beauty spectrum. (Should we avoid talking about fatness and thinness at all? That’s a whole different issue with arguments both ways.)

Such information is offset by the fact that many of Munro’s character descriptions include a line about how the person we see is not the real person at all.

Mr. Travers never told stories and had little to say at dinner, but if he came upon you looking, for instance, at the fieldstone fireplace he might say, “Are you interested in rocks?” and tell you how he had searched and searched for that particular pink granite, because Mrs. Travers had once exclaimed over a rock like that, glimpsed in a road cut. Or he might show you the not really unusual features that he personally had added to the house—the corner cupboard shelves swinging outward in the kitchen, the storage space under the window seats. He was a tall, stooped man with a soft voice and thin hair slicked over his scalp. He wore bathing shoes when he went into the water and, though he did not look fat in his clothes, a pancake fold of white flesh slopped over the top of his bathing trunks.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

- Mr Travers’ manner of speaking

- His special interests

- Physical description

- Voice description

- How he is different underneath (under his clothes)

Grace was wearing a dark-blue ballerina skirt, a white blouse, through whose eyelet frills the upper curve of her breasts was visible, and a wide rose-colored elasticized belt. There was a discrepancy, no doubt, between the way she presented herself and the way she wanted to be judged. But nothing about her was dainty or pert or polished, in the style of the time. A bit ragged around the edges, in fact. Giving herself Gypsy airs, with the very cheapest silver-painted bangles, and the long, wild-looking, curly dark hair that she had to put into a snood when she waited on tables.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

- Grace’s clothing

- Her sexualisation of herself

- How she is different underneath (she doesn’t feel as sexual as she dresses)

- A description of her ‘falseness’, as viewed from a character’s POV rather than an objective narrator’s. (In the wider context, this would be how same-age men tend to see her.)

- A detail of her clothing (the snood) which marks the earlier era

Mrs. Travers, however, was barely five feet tall, and under her bright muumuus seemed not fat but sturdily plump, like a child who hasn’t stretched up yet. And the shine, the intentness, of her eyes, the gaiety that was always ready to break out in them, had not been inherited. Nor had the rough red, almost a rash, on her cheeks, which was probably a result of going out in any weather without thinking about her complexion, and which, like her figure, like her muumuus, showed her independence.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

There was a change in his voice—a crack in it, a rising pitch that made her think of a television comedian doing a rural whine. Under the kitchen skylight, she saw that he wasn’t as young as she’d thought. When she’d opened the door, she had been aware only of a skinny body, the face dark against the morning glare. The body, as she saw it now, was certainly skinny but more wasted than boyish, affecting a genial slouch. His face was long and rubbery, with prominent light-blue eyes. A jokey look, but a persistence, too, as if he generally got his way.

Alice Munro, “Free Radicals“

- Height

- BMI

- Usual clothing

- Comparison to a child

- Her eyes, as windows into her soul

- The way in which her appearance has been affected by her actions

She was a slim, suntanned woman in a purple dress, with a matching wide purple band holding back her dark hair. Handsome, but with little pouches of boredom or disapproval hiding the corners of her mouth. She left most of her dinner untouched on her plate, explaining that she had an allergy to curry.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

- BMI

- Skin tone

- Clothing

- How her handsomeness does not match her attitude

- Her allergy to curry, which the reader is encouraged not to take seriously

His hands didn’t feel drunk, and his eyes didn’t look it. Nor did he look like the jolly uncle he had impersonated when he talked to the children, or the purveyor of reassuring patter he had chosen to be with Grace. He had a high pale forehead, a crest of tight curly gray-black hair, bright gray but slightly sunken eyes, high cheekbones, and rather hollowed cheeks. If his face relaxed, he would look sombre and hungry.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

- How he is now different from how he presented at first

- His duplicitous way of talking, which is simply a matter of changing register— we all do it, but here we are encouraged to suspect him of something sinister

- The dimensions of his face

- The colour of his hair (indicating middle age)

- How the main character imagines his face might look different. She’s really observing him closely.

She is a lean eager-looking woman with a mop of pewter colored hair and a slight stoop which may come from coddling her large instrument, or simply from the habit of being an obliging listener and a ready talker.

Alice Munro, “Fiction”

- BMI

- hair style and colour

- pose

- two lifestyle possibilities about why she may have adopted that pose, together telling us all we need to know about this character

DESCRIPTION AND WRITING STYLE

If you read a plot summary of an Alice Munro story, sometimes you’ll be left baffled: How can that be a story? What’s the climax? Any story at all can sound ridiculous when summarised, but with Alice Munro it’s often easy to do: A woman visits an old friend and reminisces about the old days. She has a few regrets. That kind of thing.

What elevates Munro’s plots, aside from the fact they are undergirded by a strong metaphorical and symbolic layer, is the detail and writing style. Alice Munro can describe dog poo like no one else. Here she is describing just that:

She didn’t see it while it was fresh, but it was fresh enough to seem an offense. Through the summer, it changed, from brown to gray. It became stony, dignified, and stable, and, strangely, Millicent herself found less and less need to see it as anything but something that had a right to be there.

“A Real Life” by Alice Munro

PLOT SHAPES

Munro resists linear narrative and emphasises multiple perspectives.

“Rasporich states that her resistance to linear narrative gives rise to multiple climaxes and multiple epiphanies: a denial of the transcendent One through the divergent many.3 Her emphasis on alternating perspectives and contingent arrangements undermines any definite position, among those being the authority of patriarchy and its gender stereotypes.Judith Butler conceptualizes gender as a system of signs infused with power.”, “Conceptualizations of gender as performance or as part of the discursive construction of subjectivities has been criticized for its lack of attention to systemic power relations which, it is argued, derives from Foucault’s apparent denial of an extra-discursive, material reality in which power is based.”

C. Nicolaescu 2014

DESCRIPTIONS OF BUILDINGS

Many authors describe buildings, but Alice Munro has a knack for describing all kinds of buildings, from the most remarkable to the most ordinary. In fact, she seems to have a special interest in ordinary buildings you’d normally walk right past.

Further along, towards the main part of town, there is a stretch of sand, a water slide, floats bobbing around the safe swimming area, a life guard’s rickety throne. Also a long dark green building, like a roofed verandah, called the Pavilion, full of farmers and their wives, in stiff good clothes, on Sundays.

“Walker Brothers Cowboy“

There was one street light, a tin flower; then the amenities gave up and these were dirt roads and boggy places, front-yard dumps and strange-looking houses. What made the houses strange-looking were the attempts to keep them from going completely to ruin. With some the attempt had never been made. These were gray and rotted and leaning over, falling into a landscape of scrub hollows, frog ponds, cattails and nettles. Most houses, however, had been patched up with tarpaper, a few fresh shingles, sheets of tin, hammered-out stovepipes, even cardboard.

“A Royal Beating”

Just before six o’clock in the evening, George and Roberta and Angela and Eva get out of George’s pickup truck — he traded his car for a pickup when he moved to the country — and walk across Valerie’s front yard, under the shade of two aloof and splendid elm trees that have been expensively preserved. Valerie says those trees cost her a trip to Europe. The grass underneath them has been kept green all summer, and is bordered by fiery dahlias. The house is of pale-red brick, and around the doors and windows there is a decorative outline of lighter-colored bricks, originally white. This style is often found in Grey County; perhaps it was a specialty of one of the early builders.

opening to “Labor Day Dinner”

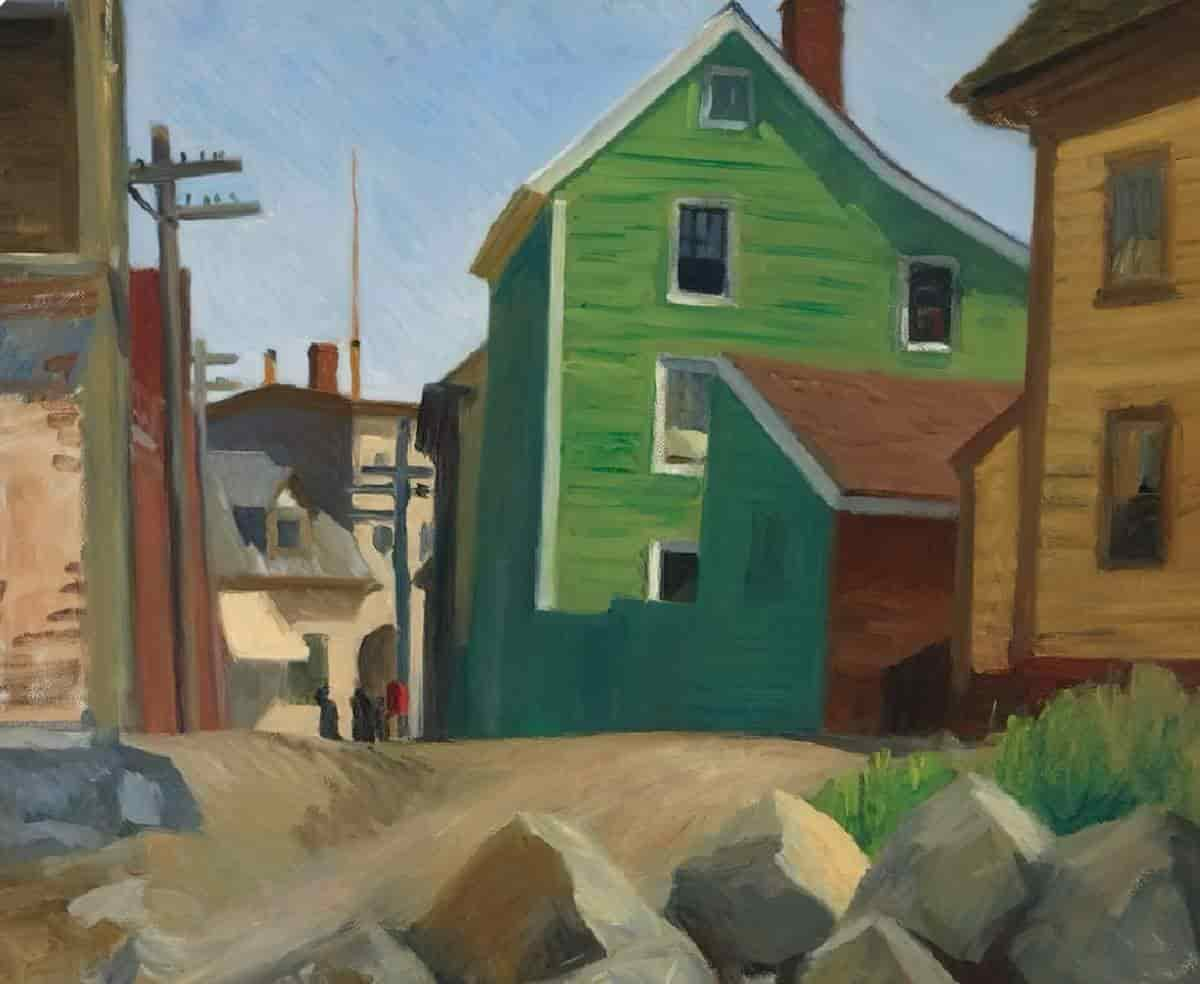

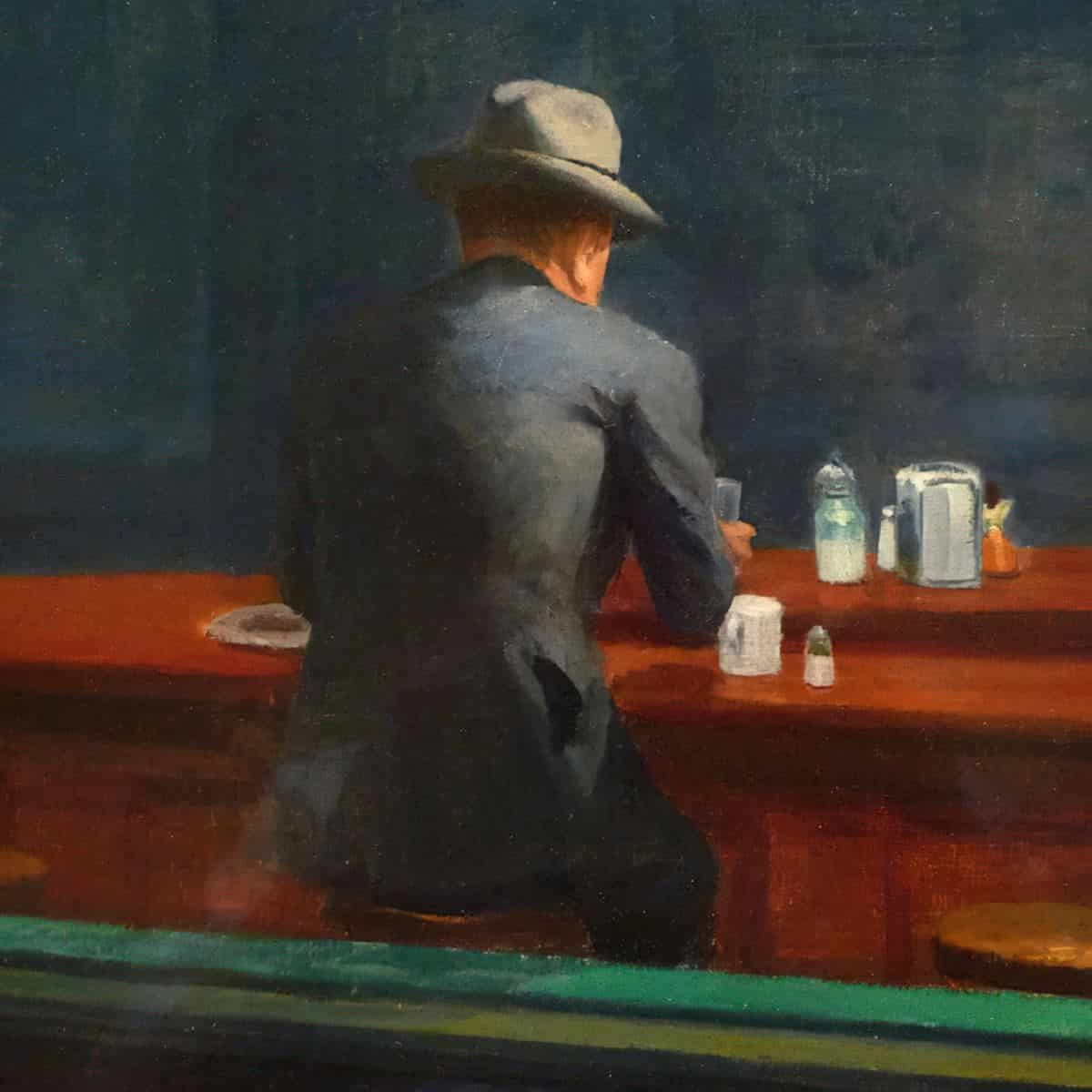

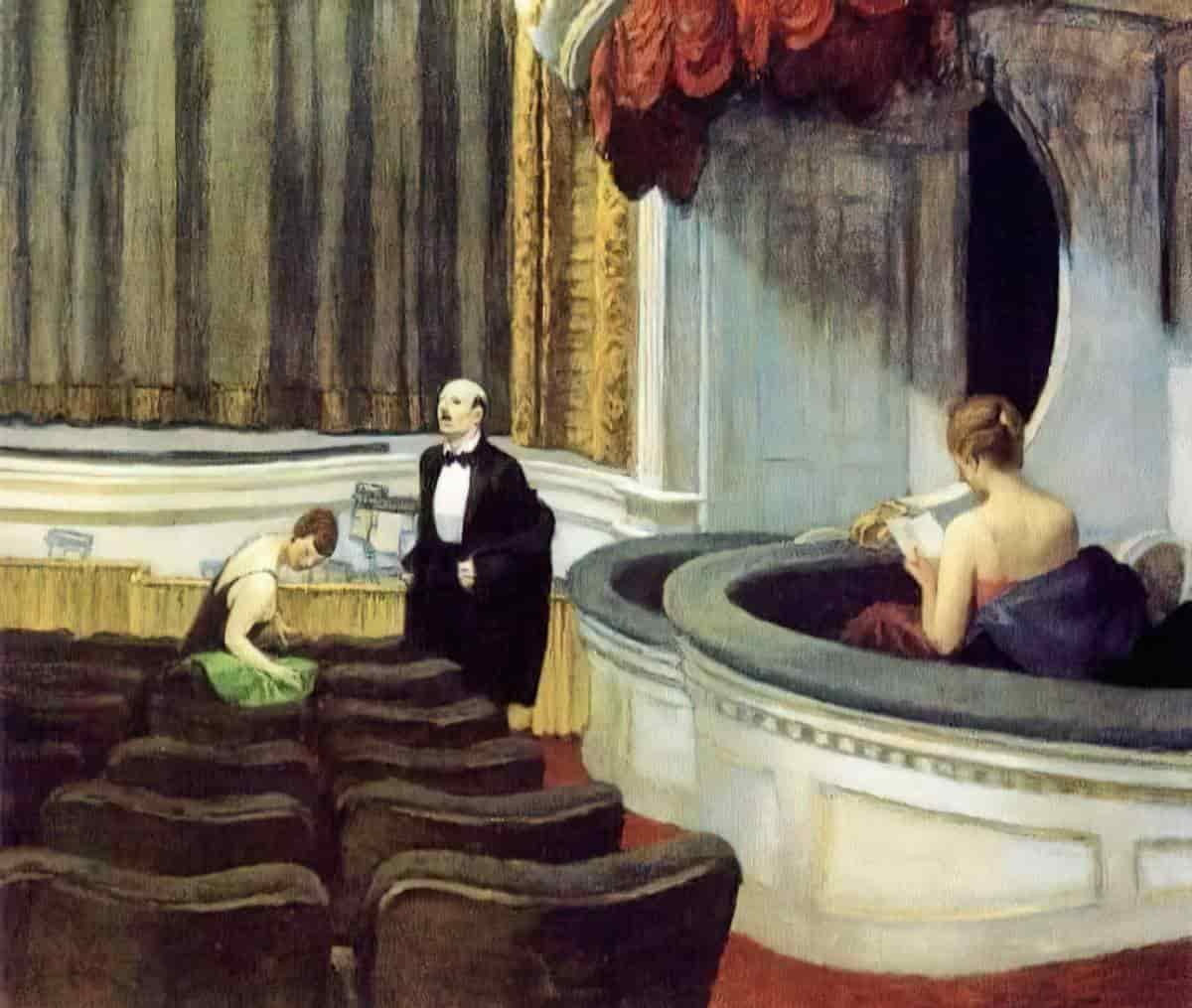

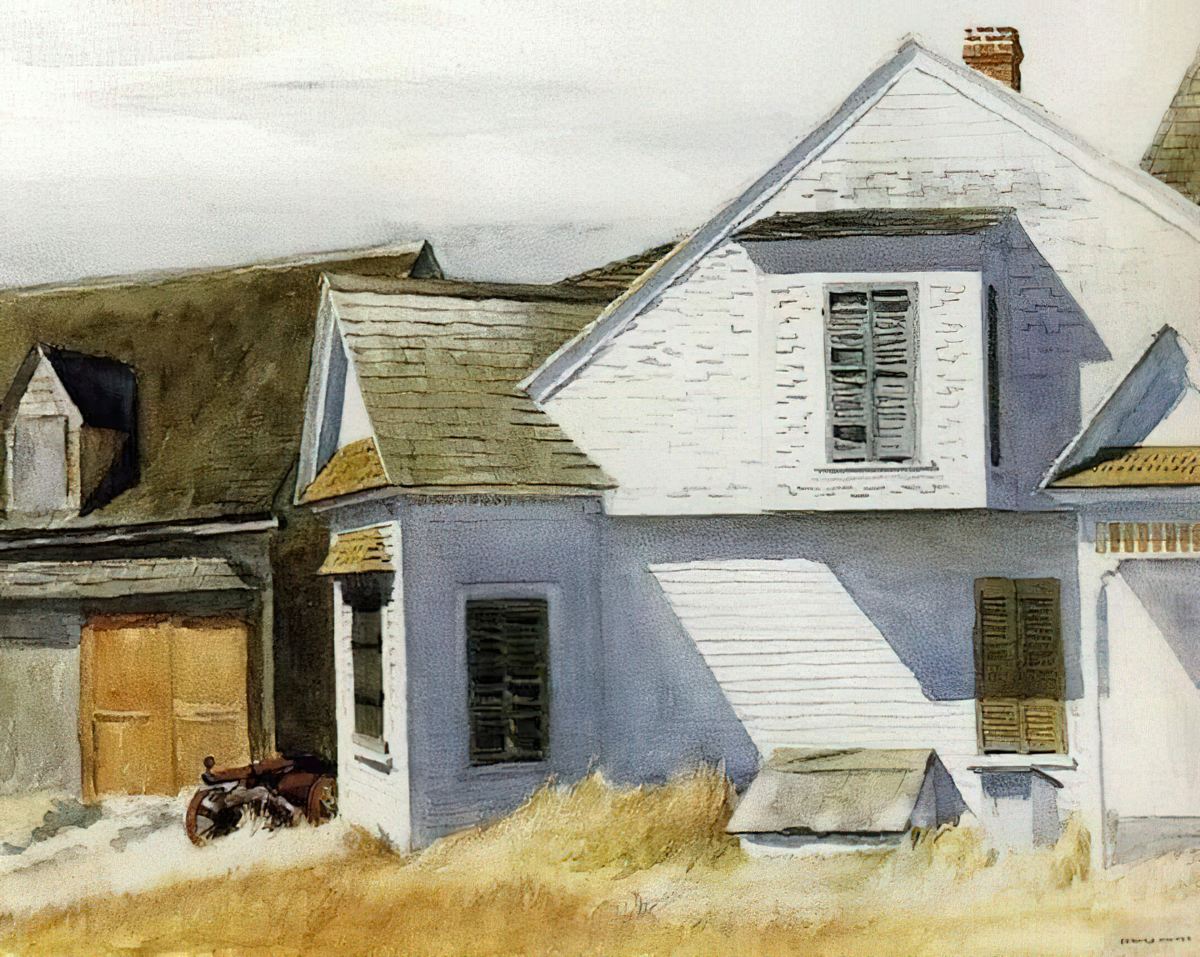

When thinking of an Alice Munro ‘impression’, think photorealistic artists like Canadian painter Ken Danby:

Think also of painter and printmaker Christopher Pratt, a Newfoundland artist whose precise, realistic paintings celebrate the mundane. Alice Munro describes ordinary buildings in great detail, the way Pratt paints them:

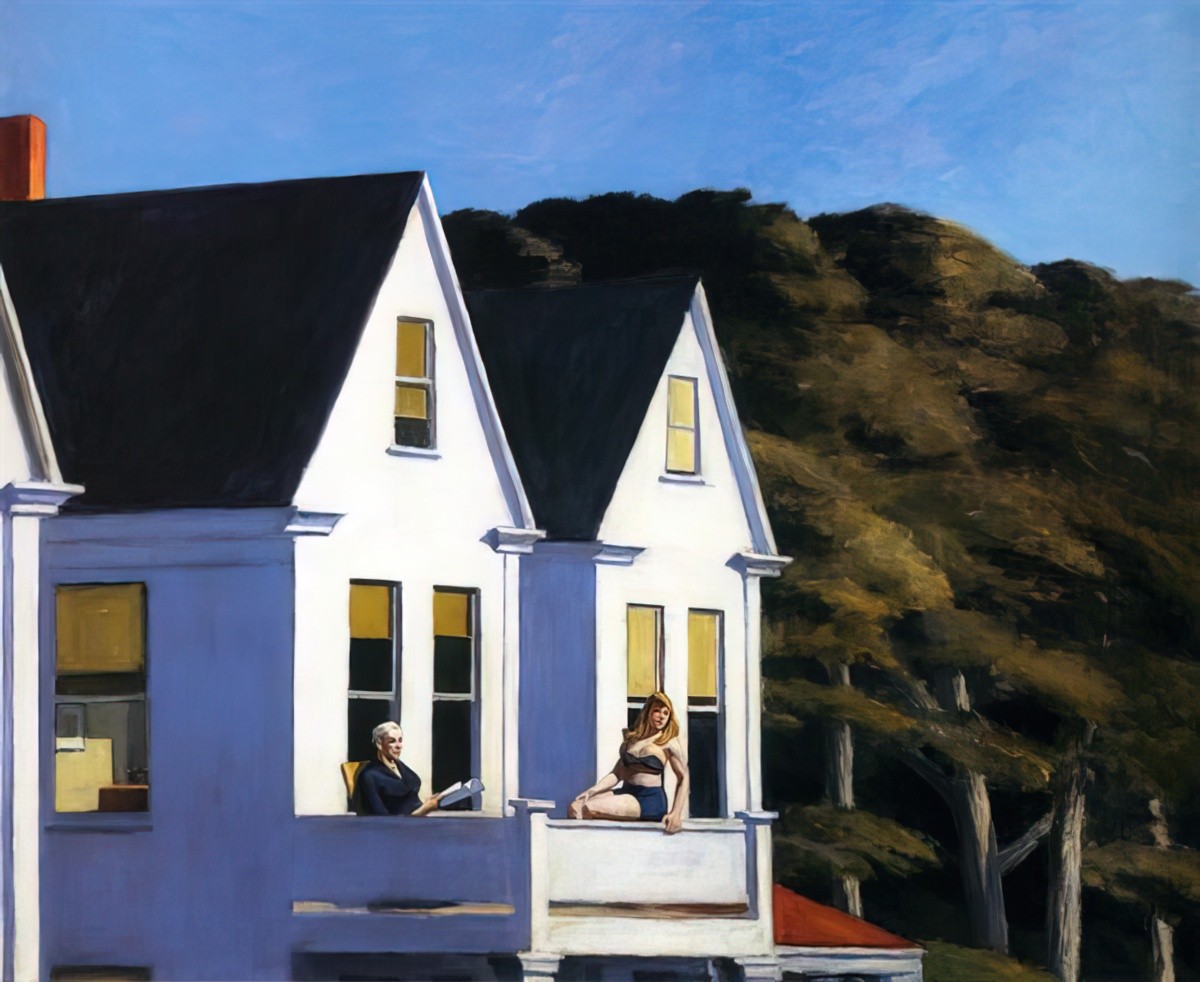

Alice Munro was also a fan of Edward Hopper.

To see a painting by Edward Hopper is often to feel loneliness in scenes from ordinary urban life. He is considered one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century but had only sold one painting by the time he turned 40.

Everything changed during his summer of love in 1923, 100 years ago, when Hopper visited Gloucester Massachusetts north of Boston and met his wife. He found the inspiration that catapulted his career.

The Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester is hosting an exhibition of more than 60 of Edward Hopper’s paintings, etchings and drawings that explore the importance of place as a catalyst for creativity. It’s called Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape Dr Elliot Bostwick Davis is the curator, and talks to Jesse.

Afternoons with Jesse Mulligan (RNZ)

STORY STRUCTURE

Munro explained that when she reads a story she does not take it up at the beginning and follow it like a road “with views and neat diversions along the way.” Rather, for her, reading a story is like moving through a house, making connections between one enclosed space and another. Consequently, Munro declares, “When I write a story I want to make a certain kind of structure, and I know the feeling I want to get from being inside that structure.”

Charles E. May

[Alice Munro] is so thoroughly a master of both structure and plot that the crafting of the work is nearly invisible; he stories often feel like effortless, half-conscious slides into another universe.

Gail Caldwell, Review of Hateship. The Boston Globe. Nov. 4, 2001

NARRATION

Alice Munro makes use of letters and frequently utilises memorized poems. (Poems are a useful means of linking generations.) Poems are also good for embedding rhythms in the mind of the reader.

NARRATIVE VIEWPOINT

Munro writes third person narratives, usually focusing on a woman, moving in and out of her head from close third person to omniscient. Narrators are often a young girl who is a careful observer of life and who has a high emotional IQ. (The stories in Dance of the Happy Shades utilise young narrators. Of the fifteen stories, eleven are told by first person narrators.)

The narrator may be looking back on her life as an older woman after having reflected on past events and gained an enormous amount of insight into humanity. These narrators characterise Munro’s later stories, in which the young woman and the elderly version seem like separate characters.

Munro’s narrator maintains an ironic distance. In this way, the author can keep her thinking (including final moral judgement) to herself, simply painting a picture then standing back, inviting readers to reach their own conclusions. She opens the door to the metaphorical house of her stories and invites us in. We’re welcome to look around, starting at any room of the house.

The girls and women of Munro’s short stories notice everything: minute details of the setting (they are probably on the highly phantasic end of the spectrum). They notice the sort of details that women and girls would more likely notice (e.g. clothing, kitchens). Her viewpoint characters also have a rich and vivid imagination. They’re able to imagine alternate lives for themselves, which can be painful for them. However, characters who lack imagination suffer the more dire consequences. The ability to imagine a better future for ourselves is the very first step towards achieving self-actualisation.

[Alice Munro] acknowledges that she wrote a lot about people’s clothes in her early stories, and credits that to not having the clothes she wanted when she was younger.

90 Things To Know About Master Short Story Writer Alice Munro

And because the rules of etiquette are more stringent for girls and women, they are keenly aware of expected standards of conduct and mannerisms of speech.

Munro also employs first-person narrative perspective, particularly when writing from the viewpoint of a child or adolescent.

Also in Munro’s toolbox: intrusive narrators, who serve to offer further insights into the hidden recesses of the main characters’ psychology. “Intrusive” is a technique, not a moral judgement on a writer’s ability to narrate. Intrusive narration is useful when the author wishes to convey information not realistically available to a character taking part in the story. Intrusive narrators offer clarification as needed, and can also penetrate the psychology of characters who don’t yet know themselves. A character’s actions then become decipherable to the audience.

DOCUMENTARY QUALITY