People do not seem to realize that their opinion of the world is also a confession of character.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Don’t waste your time with explanations: people only hear what they want to hear.

Paulo Coelho

MUCH COMMUNICATION IN FICTION IS MISCOMMUNICATION

HOW TO PUNCTUATE DIALOGUE

For a practical overview of dialogue mechanics, see chapter 5 of ‘Self-Editing for Fiction Writers: How to edit yourself into print’ by Renni Browne and Dave King.

There is plenty of room for poetic licence in fiction but when it comes to punctuating and attributing dialogue, there are rules. First, some technical terms…

1. DIALOGUE ATTRIBUTION

How the writer lets the reader know who is saying what.

‘I gotta take a leak,’ he said.

‘Wait here,’ she whispered.

2. A BEAT

A bit of physical action that lets us know who just spoke and also a little bit about what’s going on.

‘The spuds are boiling over.’ Mary turned down the element.

‘Did you just fart?’ He pinched his nostrils between his forefingers.

THE GUIDELINES

1. Don’t use adverbs in dialogue attribution.

‘Bugger off,’ she said nastily.

‘I love you,’ she said lovingly.

If the dialogue itself doesn’t show the emotion then make the dialogue better. But sometimes you do need an adverb. In that case, it’s the fashion to add it after a comma.

Is there a place for adverbs in dialogue attribution? Absolutely. Just make it unexpected. Also, for whatever reason, it sounds better (more modern) if you add a comma before the adverb.

‘I love you,’ she said, bitterly.

2. It’s ‘Tom said’, not ‘said Tom’.

Unless you’re writing children’s books, in which case there’s a bit more leeway.

3. Dialogue attribution comes AFTER the dialogue, not before.

Tom said, ‘Did you just fart?’

‘Did you just fart?’ said Tom.

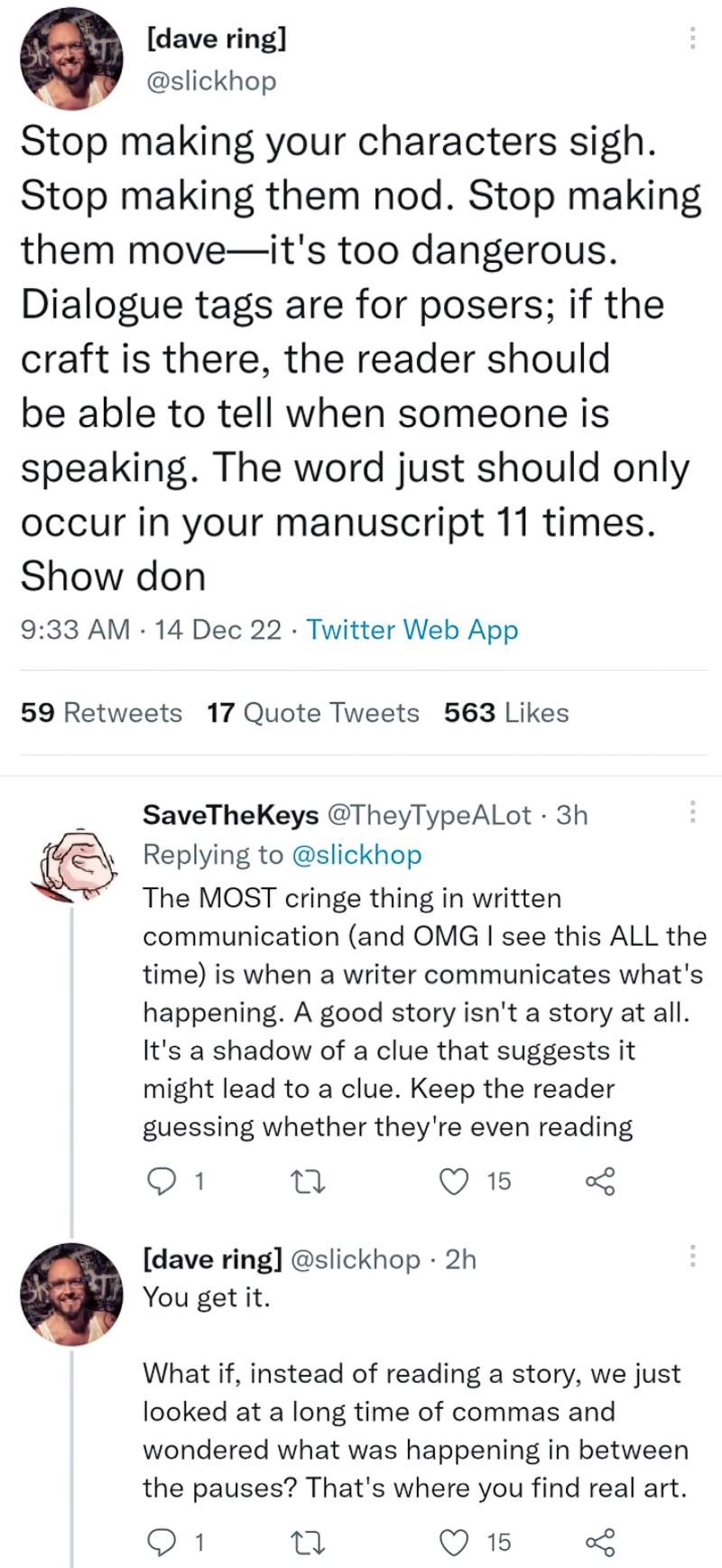

4. Don’t get fancy with synonyms for ‘said’.

“I’m not going to come!” he ejacul*ted.

“That’s the day you won the cricket match,” she chirped.

A writer can get away with a bit of asking and whispering, replying and asking but, most of the time, ‘said’ does just fine. This verb is not subject to the rules applied to other verbs i.e. choose the most descriptive one and vary it. ‘Said’, in dialogue attribution, should be treated more like a form of punctuation. It goes under the radar of readers, allowing them to focus on the dialogue itself.

‘Did you just fart?’ spluttered Tom.

‘The spuds are boiling over,’ exclaimed Mary.

5. When you find you’ve got too many ‘saids’ in your dialogue, leave out some of the dialogue attribution altogether.

This can be done by making use of beats. Put the beat on the same line as the dialogue and the reader will know who just said it.

‘Did you just fart?’ Tom stood up and started fanning frantically with his notepad.

We’re now dealing with irony. Irony makes everything more interesting, even body language beats. The same applies to adverbs in dialogue tags — it’s more likely to work if the detail you give is unexpected.

- “I totally agree,” she said, shaking her head behind his back.

- “Everyone should eat their greens,” he said, “because greens are good for gut flora.” He opened the bin and tipped the salad in.

- “I am listening to you!” She kept her gaze on the guy outside.

There you have it. The five rules writing of dialogue, summarised.

HOW DO YOU USE BEATS IN DIALOGUE?

*Don’t confuse this meaning of ‘beat’ with what theatre folk mean when they say beat — brief pauses in the action. Theatre peeps use the term ‘stage business’ when talking about these kind of beats.

Types of Gestures

Researchers have identified five different types of gestures that most of us use while speaking, although we usually are barely aware that we’re doing it. In deictic gestures, you point or gesture to a (real or implied) person, thing, or direction. Iconic gestures represent things or actions, such as when you make the gestures of turning a reel while describing how you reeled in a fish. Metaphorical gestures help us express abstract concepts, for instance when we spread out our arms to indicate the whole world. Symbolic gestures are gestures whose meaning we’ve all learned, for example, bringing your thumb and forefinger together to signal “OK” or raising your middle finger to signal… well, you know

And then there are motor gestures, some of the most commonly used gestures of all, which work to reinforce the cadence of what we are saying. As an extreme example, think of someone hitting the top of a table while shouting, “Listen to me!” That kind of gesture, called a beat gesture, can also be a simple lifting of the hands to emphasize the most stressed syllables of what you are saying. Beat gestures are a real aid to listeners’ remembering what you said, the study found.

This Simple Change to How You Speak Makes What You Say 20 Percent More Memorable, Research Shows from Inc. Australia

Some writers are more cinematic than others, writing almost as if describing a scene on screen. Cinematic writers will be making heavier use of gestures.

COMMON BODY LANGUAGE BEATS

But it’s easy to go too far in the other direction and cut every single instance of something which can become problematic but which, mostly, isn’t.

EXAMPLES OF BODY LANGUAGE BEATS IN THE WILD

- She mashed her lips into a tight line. (Mashed potato)

- Nina purses her lips in a tight line and rolls her shoulders. (‘Pursing’ is a different action from forming a line. Rolling shoulders sounds like something you do at tennis cool down.)

Body language beats can be especially problematic in first person narratives, though not every reader seems to notice or care about this. The problem some readers have with first person — or even with close third person — is that the character / narrator can’t see into another character’s mind without ‘head hopping’. (I have a few issues with this old writing group chestnut.) So what do writers do to get around this limitation? They do as well all must in real life — their characters interpret others based solely on body language.

BODY LANGUAGE BEATS IN COMEDY WRITING

Comedy gives writers more scope for originality and hyperbole. Like how it’s easy for horror to slip into comedy, it’s also easy for body language to sound unintentionally humorous. But comedy writers can make the most of this.

Squirrel Girl is a Marvel prequel by Shannon and Dean Hale:

- Ana Sofia’s eyes widened even wider. (Intentional repetition, and also a bit meta because these characters have massive, cartoonish eyes.)

- She looked up. She was still frowning, but her eyes weren’t into it. (The eyes deliberately have a life of their own.)

Pax by Sara Pennypacker is a literary, non-funny MG. Despite writing for children, Pennypacker uses strong verbs not often used in spoken English:

- The man had followed him outside. He yanked a thumb over his shoulder. (Pennypacker uses the verb ‘yank’ several times. Other authors say things like ‘hiking a thumb’ in a certain direction.)

- At the corner, he risked a glance over his shoulder. (NOT: At the corner, he glanced over his shoulder. This is doing a lot more work.)

- Vola dropped a handful of nails into an overall pocket and slide a hammer into her belt loop. Then she levelled him a gaze. (NOT: Then she gazed at him. She’s doing this deliberately, sending him a message.)

HOW DO EXCELLENT WRITERS MANAGE BODY LANGUAGE BEATS?

It’s not easy to describe body language and some writers are much more interesting about it than others. Here’s an example I love from Annie Proulx:

“The money is good,” said Verna, giving the porch floor a shove that set the glider squeaking. Her apron was folded across her lap, her arms folded elbow over elbow with her hands on her shoulders, her ankles crossed against the coolness of the night. She wore the blue acrylic slippers Santee had given her for Mother’s Day.

“The Unclouded Day” by Annie Proulx

That reads effortlessly, yet the pose is difficult to describe succinctly.

From the same story we have a different kind of woman altogether:

“Knock those beadies dead, Earl,” said the wife, drawing her fingernail through a drop of moisture that had fallen from her drink onto the chair arm.

Verna is not only cold, but she’s also in opposition to her husband. Even her apron, ‘folded across her lap’ seems against him.

Annie Proulx knows how to weave psychology into body language:

Snipe introduced himself after the song ended and gave them a broad, glad-hand smile like a proof of good intent. They didn’t care who he was, barely looked at him, and he darkened with embarrassment.

“Ah,” said Snipe, grinning like a set of teeth on a dish.

“Heart Songs” by Annie Proulx

Here’s another technique utilised by Annie Proulx:

Walter said there was no point in trying to understand what it mean. “It can’t mean anything to us. It only meant something to the one who puts this negative in the tobacco can.”

Buck, wearing a scratchy wool sweater next to his skin, said something under his breath.

“Negatives” by Annie Proulx

Notice how Proulx didn’t say: ‘Buck said something angrily under his breath’. She told us he was wearing a scratchy wool sweater next to his skin and we deduce that this is part of his anger, perhaps contributing to it. I consider this a form of pathetic fallacy—although it’s not the sweater that’s angry—indeed, it’s not even the reason for his anger, the feeling is transferred/attributed to something tangential—the sweater. I love this technique, as people in real life often don’t realise what’s really bothering them in the moment. This technique would be very well suited to a character who is not good at reading their own emotions.

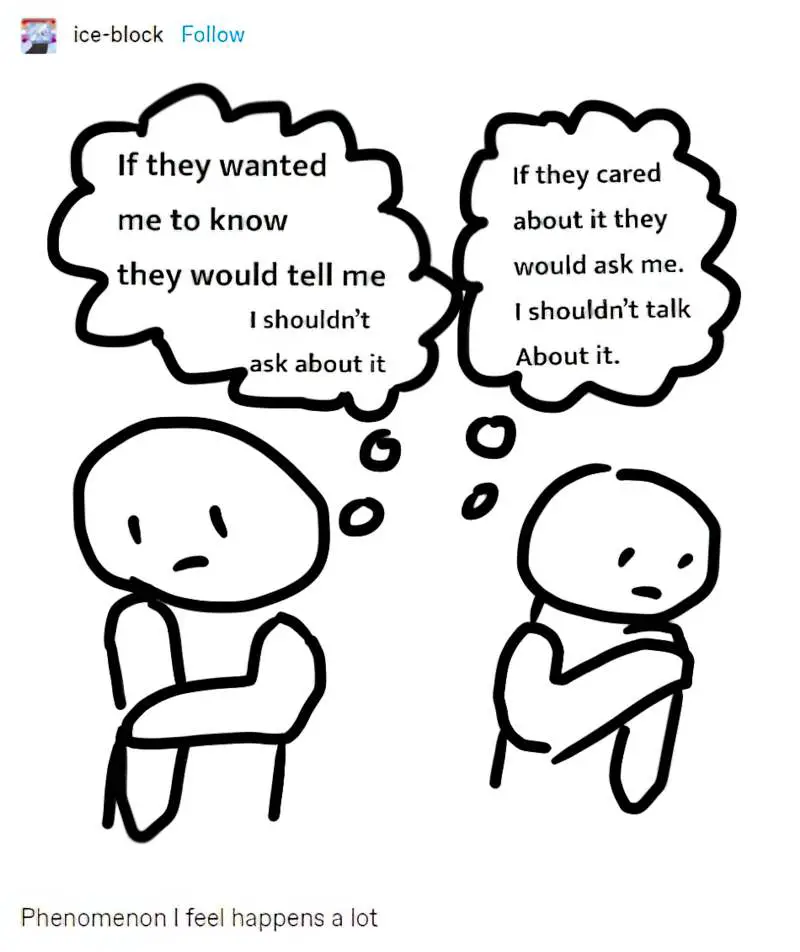

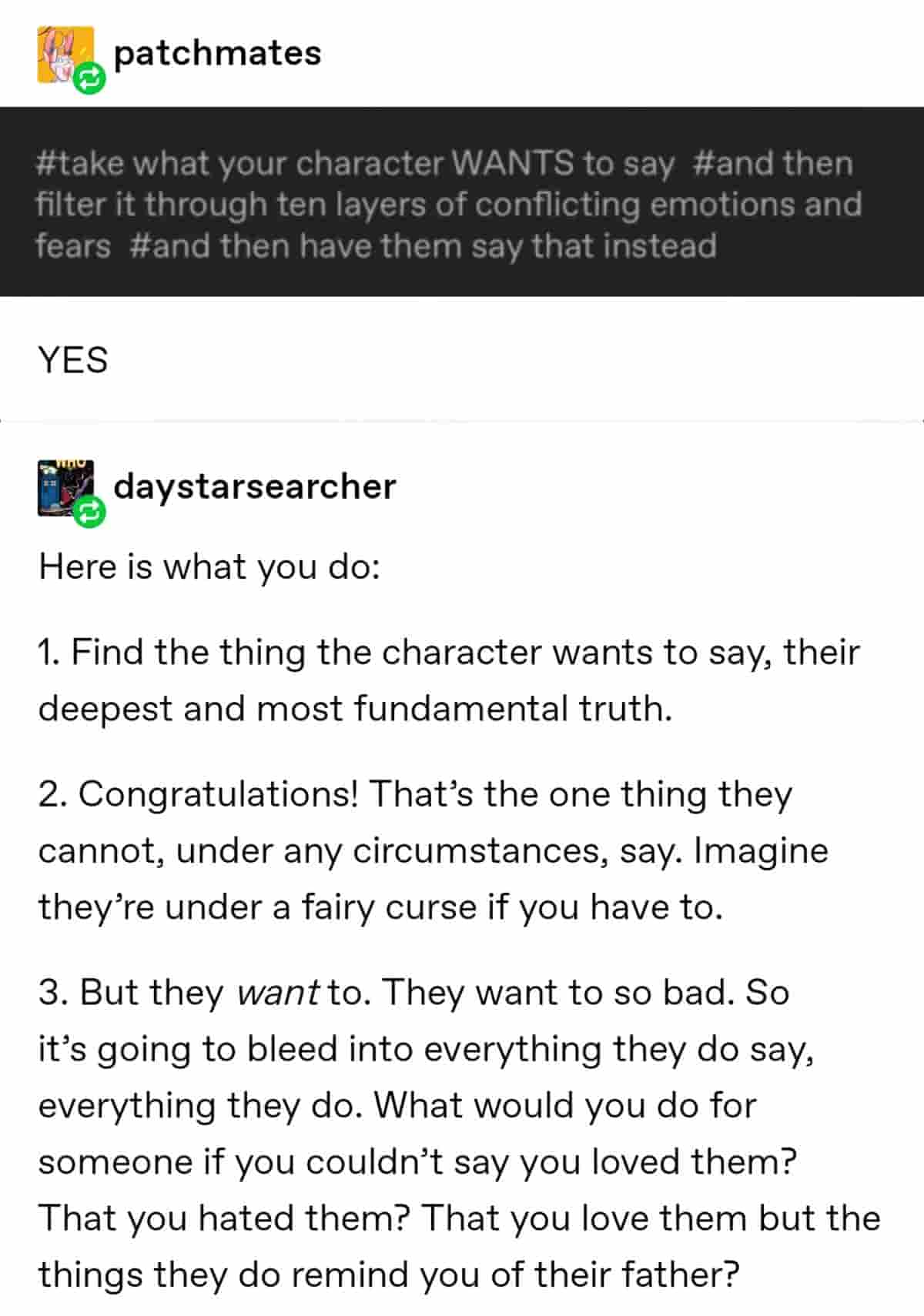

Know your characters. Are they the sort of person who can accurately read their own emotions? How long does it take for them to process how they feel? Even once they’ve worked that out, do they talk about their emotions with others?

In “Runaway“, Alice Munro describes bursting into tears:

She didn’t do anything to avoid Sylvia’s look. She drew her lips tight over her teeth and shut her eyes and rocked back and forth as if in a soundless howl, and then, shockingly, she did howl. She howled and wept and gulped for air and tears ran down her cheeks and snot out of her nostrils and she began to look around wildly for something to wipe with.

“Runaway” by Alice Munro

When writing body language beats it is so easy to fall into accidental comedy or hyperbole. Adelle Waldman avoids hyperbole but skirts close to it in her wonderfully (intentionally) cringeworthy satire of a modern feminist man navigating the dating world. This is a description of Nathaniel’s best male friend:

“Hannah, Hannah, Hannah,” Jason said. He was leaning on the roof’s railing with his arms extended on either side of his body and his ankles daintily crossed. When he smiled, his wide jawline formed a gratuitously large canvas for his fleshy lips. In his head’s narrower, more delicately constructed upper half, his eyelashes fluttered in a show of affability as disingenuous as the upturn of his mouth.

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. by Adelle Waldman

Sometimes, top-notch writers — the writers described as having excellent prose — avoid body language beats entirely. On the other hand, in real life people do nod and grin and shrug. We don’t have to make a seven course meal out of every beat. Excellent literary writers do use them. The trick is to make the boring beats totally invisible and embellish the meaningful ones. Embellishing a body language beat is similar to embellishing ‘said’. If you’re gonna do it, better be good.

Alice Munro:

The doctor looked directly at Meriel. This was not a disagreeable look—it was not aggressive or sly, it was not appraising. But it was not socially deferential, either.

[…]

She had started to cough, tried speaking through the cough, gave up, and hacked violently. The doctor got up and struck her expertly a couple of times on her bent back. The coughing ended with a groan. […] She coughed again, though not so desperately as before. Then she raised her head, breathed deeply and noisily for a few minutes, holding up her hands to stall the conversation, as if she would soon have something more, something important, to say. But all she did, finally, was laugh and say, “Now I’ve got a permanent blindfold. Cataracts. Doesn’t get me taken advantage of, in any debauch that I know about.”

Alice Munro, “What Is Remembered“

Neil looked up from his computer and leaned back in his chair. He joined his hands together and made a steeple of his index fingers, which he placed under his chin, as if he was Confucius contemplating a deep philosophical truth about the universe rather than the boss of a musical equipment shop dealing with a late employee. There was a massive Fleetwood Mac poster on the wall behind him, the top right corner of which had come unstuck and flopped down like a puppy’s ear.

from The Midnight Library, a 2023 novel by Matt Haig

How do excellent writers set out their dialogue scenes?

We’ve already covered how to punctuate (above) but there’s more to creating good dialogue paragraphs than punctuation.

- Body language beats, where used, are original (you won’t have read it elsewhere).

- Body language beats are utilised to either speed up the pace (fewer / zero beats) or to slow it down (longer beats).

- Each beat is meaningful. It tells us something about the character’s desire/motivation/interiority as well as the surface information of stage direction. Never just one purpose. Several, layered. Never just ‘to break up the page’.

- Emphasise irony. A character nods while disagreeing, or folds their arms while agreeing.

- Some of the more experimental writers have a non-standard way of writing dialogue scenes, for instance with dashes and no speech marks. While this can read as irritating and pretentious (what, you too good for standard punctuation?) I’m sure these writers do it to avoid the pitfalls that come with the conventions. Not all genres, categories and publishers will accept non-standard dialogue layout, though.

- They may write with very little dialogue, and when there is dialogue, it lasts no longer than about three lines at a time. This means there’s no need to remind the reader who is saying what. But some types of books are dialogue heavy by their nature. It’s harder craft a book length worth of original body language beats in these stories.

- A tongue-in-cheek tip in episode three of the Print Run podcast: Write every scene like it’s a sex scene. This is because when writing sex scenes, it’s rare to fall into the usual traps. When you’re really focusing on the way bodies move in time and space, you’re giving body language the attention it deserves. Also, when you’re writing dialogue, in the first draft you’re mostly consumed with what your characters need to say, and don’t have the headspace to think of original body language beats at the same time. So unless they’re erased in a subsequent draft, unless they’re horrendous, there’s a danger they’ll stay there. In fictional sex scenes, characters usually aren’t doing much talking to each other (a discussion for another day). #NotAllSexScenes — see also The Bad Sex In Fiction Award, because when beats in sex scenes go wrong, boy to they go wrong.

Characters need a goal in each scene, and the other characters need to be the obstacles in their way, literally and figuratively. You already know human interactions have “push and pull,” so why not physicalize that? Let them actually shove or yank on each other. For physical interactions, I generally stick to a “one-touch” rule: Two characters should touch each other once, and only once, in each scene.

Excerpt From: Matt Bird. “The Secrets of Story.”

DIALOGUE TAGS AND BEATS: A COLLECTION FROM RANDOM READING

These look like nothing much on their own but are taken from famous works of literature. Bear in mind, I’ve left out all the unmarked ‘saids’ and ‘asked’, which form the majority of dialogue tags.

- said X with no emphasis

- … looking for satire

- he said testily/seriously

- His voice was teasing.

- X insisted

- X’s eyes slipped over Y’s face

- without looking around

- X said: “Y”

- stared questioningly at him

- howled out the name of

- regarded it broodingly

- in politeness

- squatted on his hams

- his fingers found a X with which to Y

- He sat up straighter against the X

- waved his X in negation

- explained, a little piqued

- he repeated

- he waved his hand in a X gesture

- he went on softly

- his face looked helpless

- His expression asked for help.

- He doubled up his legs and scratched between his toes.

- X, fumbling with his Y,

- X pulled his hat down low over his eyes

- X surveyed Y critically

- looked at it with some admiration

- came into the X with a swaying strut

- his shoulders relaxed

- X tried to control his question.

- X thrust out his bristly chin, and he regarded Y with his shrewd, mean, merry eyes.

- X looked outward from his seat on the Y.

- X appealed to them all suddenly

- His eyes were wet and shining.

- coughed delicately

- his mind was cataloguing Y

- X looked startled.

- They fell silent while

- said X, speaking to no one, addressing the group

- stirred restively, but held her peace

- made his report solemnly

- was rosy with the compliment

- X looked at the face of Y for dissent

- a muffled voice replied from X

- X’s voice sounded strange to his own ears

- X gave a humourless laugh

- X arranged her expression into one of martyred patience.

- X held Y a beat longer than necessary.

- X said in an undertone

- with a thousand-yard stare

- “[dialogue]” she swallowed, “[more dialogue].”

- X whipped his head around

- X’s eyes wandered over Y, as if trying to memorise it.

- listlessly watching

- X felt something in him relax a fraction

- X looked at Y in distaste

- X aimed for a neutral tone, fell well shy

- X’s defiant look answered Y’s question

- X ran a hand over his face

- “[dialogue],” he had said when X told him Y.

- X studied Y as they followed him towards the Z.

- X took off his Y and fought to keep the look of Z off his face.

- X’s blue-veined hands trembled under the weight of a Y.

- X hastily took the Y from Z.

- X sat down shakily with an irritated sigh.

- X snapped as Y

- X’s vowels carried a trace of a Y [accent]

- X’s laugh sounded like a Y

- X waved at Y to sit down on the Z

- X stared at Y in a shrewd way

- X put on his hat, adjusting it at a rakish angle

- X looks up, as if emerging from a trance, and in a half-distracted way reaches for the Y and waves it in my direction

- X waited, impassive, until…

- with a furtive glance from beneath lowered brows X…

- His lips are pursed. He is holding his breath.

- Said with mild disapproval.

- X raises her hand, palm outward. Y raises his, a mirror of hers.

- His eyes were sharp and interested.

- X looked shyly at him.

- X’s eyes dropped to the ground.

- His eyes were warm.

- His independent hands rolled a cigarette.

- A truculent look

- held his mouth tight and small

- opened his mouth to speak

- face was rigid

- drew up his feet and clasped his legs

- X sat regarding Y

- His half-closed eyes brooded as he looked at the Y.

- yawned and brought one hand back under his head.

- …wonderingly, as if he had told himself the fact.

- “X”. And then, still informing himself: “Y”.

- HIs eyes glittered with malice.

- observed brightly

- raised a shrill voice

- emerged from X, sat up, then stood up and moved towards the Y

- protested

- They walked into the X together.

- X clamoured

- X focused his eyes fiercely until he recognised Y

- ran his fingers through his hair nervously

- X bowed his head

- folded her hands over her stomach

- X kept one mean eye on the Y

- in his tone not supplication but conjecture

- bleated

- she rocked a little, back and forth

- X looked around

- X paused

- There was no talk until…

- X watched Y as he ate, and her eyes were questioning, probing, and understanding. She watched him as though he were suddenly a Y….

- X stood up, his chair squealing against the floorboards.

- X said with a flourish, like a conversational trump card.

- X felt the air go out of him.

- X forced himself not to shake his head.

- His legs felt like they wouldn’t hold him up.

- X felt an ache swell in his chest.

- X took a sip of Y without taking her eyes off the Z.

- X closed her eyes and tilted her head back sharply.

- X took a deep breath, her features creasing.

- X suppressed a smile

- X said with a wan smile

- X glanced up, saw Y’s appraising stare

- X rocked back in her chair. Placed her hands gently upon the table.

- X said, feeling the pulse in her throat.

- X made a point of keeping his voice steady

- X gaped at

- X twisted her face into a picture of innocence

- X smoked slowly, blowing the vapour into the hot night sky.

- X took a drag. Suppressed a cough.

- X paused, remembering.

- A phone intercepts.

- X said, setting her glass down with monumental care.

- X said with arched brows

- X raised her glass, all the acknowledgement and surrender she could manage.

- X gave a diffident nod but Y knew she wasn’t buying it.

- X smiled, enduring Y’s benevolent gaze

- X smiled and for Y it smarted.

- X looked surprised, even concerned

- X stubbed the cigarette out carefully, then doused the butt with a splash of beer.

- With a wave, X headed off into the night.

- X shifted uncomfortably at the thought.

- X sighed and rolled over, his fingers hovering over his phone as he considered Y.

- X held Y’s gaze, but Z felt she was forcing herself.

- X made a little noise of disbelief

- X straightened his spine like a man fortified by the knowledge he’d been right all along.

- X drained her glass in the way of one making a decisive gesture

- X ambles up the Y in her slow, absent-minded gait.

- X lopes down the hallway to Y

- X beams, alive with the wonder of Y

- X has sagged in her chair, nervous and ill at ease

- X sets her cup back on her saucer but her hand trembles

- The words were on my lips but did not escape them.

- X holds up his hands as if to say: Y

- she said, in that affectless way of hers

COMBINING GESTURES AND DIALOGUE

Some writers say that you know you’re ready to start writing when the characters start talking to you. Once characters start talking in your head, it starts to feel like this:

Characters are not created by writers. They pre-exist and have to be found.

Elizabeth Bowen

Although reading and making gestures comes naturally for most people, the study of gestures (kinesics) might bring a few things to into focus.

Questions To Ask About Gestures When Writing

- Are you writing in a low contact or high contact culture? (Would these people be touching each other as part of their communication style?)

- When characters touch others, what does this mean? (Can be multi-layered.)

- Is this in line with what we’d expect from their gender expression/social hierarchy/cultural background?

- When characters touch themselves (no, not like that), does it indicate some psychological state, or is it out of habit?

- Have you differentiated between different characters by giving them different body language? Some might use self-focused adaptors, others might use an object.

- Which of your characters have the most intense eye contact? Which of them avoid eye contact?

A comprehensive Internet resource is A Primer on Communication Studies, available free under a Creative Commons licence.

Interesting Takeaways From Kinesics

Gestures are culturally variable although a few are universal.

The main types of gestures are manual (ie. involve the hands). Peter A. Andersen distinguished between three different types of gestures:

- ADAPTORS: touching behaviours and movements that indicate internal states typically related to arousal or anxiety. These can be self- or object- focused. Throat clearing would be a self-focused adaptor. Fiddling with a pen would be an object-focused adaptor.

- EMBLEMS: gestures that have a specific agreed-on meaning. In other words, emblems are the gestural equivalent of a (universal) symbol. However, emblems are not ‘universal’ because many are so culturally specific.

- ILLUSTRATORS: the most common type of gesture. Illustrates the verbal message they accompany. Using hands to indicate the size or shape of an object is a classic example of an illustrator gesture. Without verbal context they don’t usually have any meaning.

Touch

The study of touch is known as ‘haptics’.

It was English psychologist Michael Argyle who said that touch is a powerful social signal because it is associated with both sex and aggression.

Touching can be divided into self-focused and other-focused. Self-focused touch is not normally intentionally communicative and may reflect the person’s current state of mind (e.g. anxiety). This is useful to writers. But sometimes self-touch can merely be a habit.

Touch and SOCIAL Hierarchy

When it comes to other-focused touch, this relates heavily to hierarchy. Doctors touch patients, ministers touch parishioners, police officers touch the accused etc.

Touch and Gender

There are a lot of self-described pick up gurus on the internet making many generalisations about gender differences in touch and body language, ascribing far too much weight to simple actions and not nearly enough weight to being an all-round decent human being.

The main gender difference to note is itself based on another thing badly wrong with society: Women engage in more same-sex touch than men do, and this is probably because of homophobia. Women offer fuller hugs whereas men tend to shake hands or a back slap before hugging each other, often with quite forceful taps and back slaps.

Studies have noticed other differences between masc- and femme- people. Masculine people do more ‘temple-support’ whereas femme people touch their hair more.

Cultural Differences

Some cultures are high-contact, others low-contact.

High contact cultures include: India, Turkey, France, Italy, Greece, Spain, the Middle East, Parts of Asia and Russia.

Low contact cultures include: Germany, Japan, England, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Estonia, Portugal, Northern Europe and Scandinavia.

These are generalisations of course, because single countries include diverse subcultures.

EXPLAIN UNEXPECTED GESTURES

Notice how Alice Munro only explains what is unexpected:

Jeffrey Toom was his name. “Without the B,” he said, as if the staleness of the joke wounded him.

He asked her if she had ever heard of a play called Euridyce. Pauline said, “You mean Anouilh’s?” and he was unflatteringly surprised.“Sons of bitches,” said Jeffrey between his teeth, but with some satisfaction. “I’m not surprised.”

“The Children Stay” by Alice Munro

An example from Larry McMurtry, which looks simple:

“You want me to live in that tent?” Mary said, with an unfriendly cast to her expression.

The Last Kind Words Saloon, Larry McMurtry

Sally Rooney is especially good at describing gestures.

He puts his hands in his pockets and suppresses an irritable sigh, but suppresses it with an audible intake of breath, so that it still sounds like a sigh.

Rooney is so very good at conveying suppressed emotion in young adults, who don’t yet have the words or confidence within their nascent relationship to express themselves, the TV adaptation of Normal People made for easy spoof fodder:

Further examples from Normal People:

Do you want some of this? Marianne says.

She’s holding out the jar of chocolate spread. He presses his hands down slightly further into his pockets, as if trying to store his entire body in his pockets all at once.

No thanks, he says.

She has a focused expression, like she’s looking through his eyes into the back of his head.

A list of three movements, separated by comma:

He nods, looks around the room for a bit, digs the toe of his shoe into a groove between the tiles.

This chapter is written in close third person with a viewpoint character of Connell, but Sally Rooney doesn’t let us all the way into his head. She reserves the right to tell readers what Connell himself can’t see. So it is with the body language:

He wipes his palms down on his school shirt unthinkingly.

Not just ‘he nods’. The nodding is garnished:

He looks at her to confirm she’s being serious, and then nods.

Juxtapositions are always good. Unless told otherwise, laughing indicates happiness:

He gives a short, unhappy laugh.

He closes his eyes, pushes his tongue against the roof of his mouth. He can hear Marianne laughing.

Stretching out the pauses, making them meaningful, is a Rooney trademark:

For a few seconds he says nothing, and the intensity of the privacy between them is very severe, pressing in on him with an almost physical pressure on his face and body.

Instead of, ‘She put on her coat and paused’:

She puts her arms through the sleeves of her coat and adjusts the collar. She’s beginning to feel nervous now and hopes her silence is communicating insolence rather than uncertainty.

He mimics her face, contorted into an ugly grin, teeth bared. Though he’s grinning, the force and extremity of this impersonation make him look angry.

Instead of ‘they both laughed’:

She had to laugh then, and he laughed because she did. They couldn’t look at each other when they were laughing, they had to look into corners of the room, or at their feet.

‘Always’ does deft work, propelling the reader through time, showing these two have gotten to understand each other a little, off the page:

Connell made the face he always made when she criticised his friends, an inexpressive frown.

Some things are so difficult to describe, reliant upon such minute musculature of the face, the only way to write it succinctly in fiction is to write the interpretation of it:

He paused for a second, like his ears had pricked up at this remark but he didn’t know exactly how to respond.

What’s masterful about this, is Sally Rooney has just described how Marianne is different around Connell, which Connell has observed: ‘If she was different with Connell, the difference was not happening inside herself, in her own person hood, but in between them, in the dynamic.’ So it is with how each character interprets the other’s thoughts and intentions by looking closely.

It always helps to put something in character’s hands:

He shrugged, bending the book cover back and forth.

She was attuned to the presence of his body in a microscopic way, as if the ordinary motion of his breathing was powerful enough to make her ill.

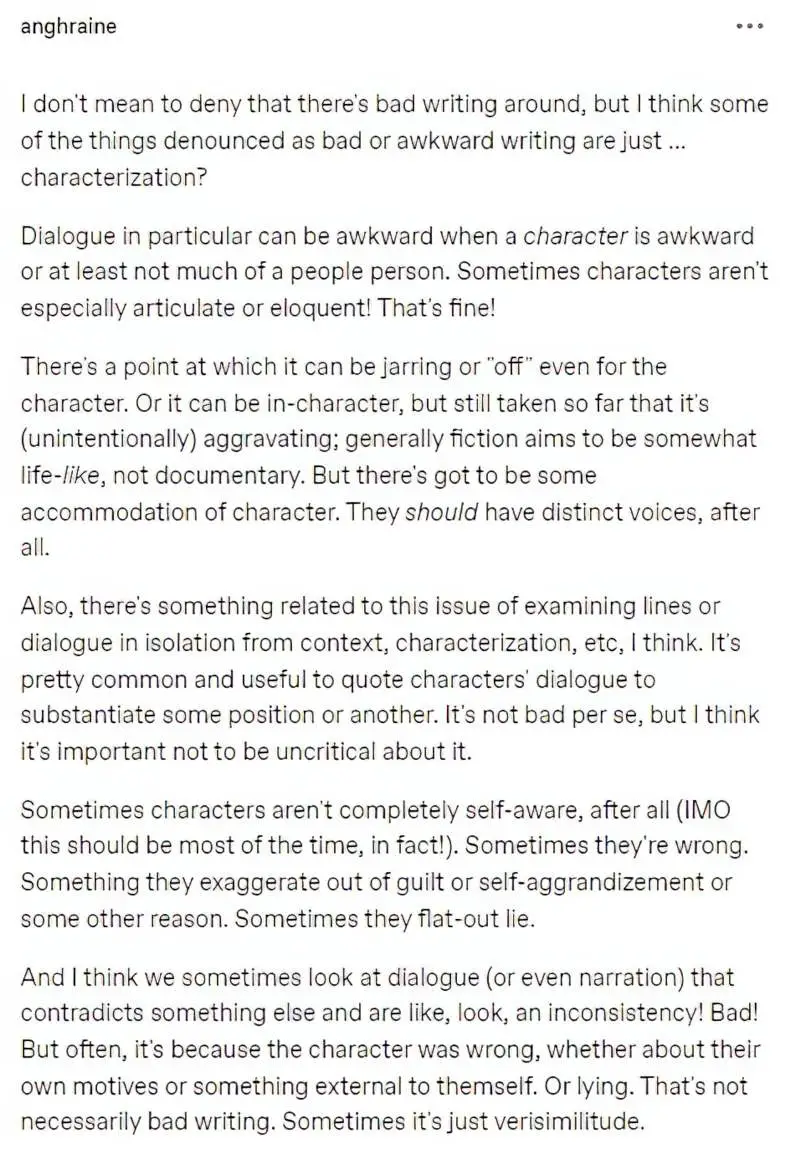

HOW TO LAYER DIALOGUE

SWITCHTRACKING

MODERN DIALOGUE IN AN OLD SETTING

Dialogue is never a transcript of real speech. It is always a believable rendition; done badly, a contrivance. Some writers are linguists who aim for a close approximation of an historical period, all the while knowing that a true transcript would not be understood by the modern reader. But in other types of stories, dialogue is so anachronistic that it draws attention to itself: It then becomes metafictive.

I’m interested in when writers can get away with anachronistic dialogue and when they cannot, because I know from experience in critique groups that there can be low tolerance for modern dialogue in old settings. It will be highlighted. Is this because I’m doing it incorrectly, or because some readers simply don’t like it, always will?

As case study, the TV series Dickinson is interesting. This series is a 2019 story based loosely on the teenage life of American poet Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886). If rendered authentically, the writers would have been writing dialogue reminiscent of upper middle class American English as it sounded in the late 1840s.

However, the writers decided not to go there. Instead, they chose to write much of the dialogue with contemporary idioms and slang, some of it inspired by the Internet.

“You’re really leaning in to this whole housewife thing, aren’t you.”

“Eat shit, Emily.”

In the official teaser trailer below, you’ll even see Emily make use of modern hand signs — signs which an 1840s audience would not understand.

Why write anachronistic dialogue?

The advantages of modern dialogue in an 1840s setting are clear: Emily is now a highly relatable character. Not only that, but Emily uses modern language where the older, less empathetic characters (e.g. her parents) do not. This is a clear clue to the audience: We are to empathise with Emily.

I also happen to be listening to the audiobook of Damascus by Christos Tsiolkas at the moment. Before downloading it I checked out a review, which included this observation, by someone who says Tsiolkas is ‘no prose stylist’:

Fortunately, his characters speak not in the stilted Charlton Hestonisms perilous to biblical fictioneers, but in blasts of steaming vulgarity that breathe pungent life into the ancient setting.

Rob Doyle in The Guardian

This demonstrates demonstrates the tightrope traversed by any writer delving into the past. By writing deliberately anachronistic dialogue, we can at least avoid the pitfall of sounding like Charlton Heston.

Sometimes, to make your characters speak as they would have would alienate them from a modern audience. This is why Downton Abbey actors speak with modern Thames Estuary accents rather than the Queen’s English of the era. Even the Queen’s English has changed within the Queen’s own lifetime. Look up her earliest broadcasts and you’ll hear the difference.

Why does anachronistic dialogue work so well in Dickinson?

For more on Emily Dickinson, listen to episode 147 of the Then Again Podcast with Dr. Christanne Miller: “Emily Dickinson has gone from being a ‘nobody” to taking her place on the world’s stage as a great poet. She was rather reclusive as an adult and therefore there are many myths and legends that have surrounded her life’s story. In this podcast episode, Marie interviews Dr. Cristanne Miller about the fact from fiction of Emily Dickinson’s life.”

MODERN DIALOGUE IS INTRODUCED EARLY

After a voice over introduction, almost the first dialogue we hear out of Emily’s mouth is, “That’s such bullshit!” This phrasing, and the word ‘bullshit’ would not have been in Emily Dickinson’s active vocabulary. Her response to fetching water from the well because she is a girl provokes a chuckle in the audience — her modern dialogue is comically dissonant. Importantly, we will now accept such dissonance, understanding it is deliberate.

THE OVERALL MOOD IS EQUALLY ANACHRONISTIC

In a TV show the storytellers can make use of all sorts of things to create a modern tone: In Dickinson’s case there’s the modern music by Tony K, Khalid, Jerrod Nieman and others.

Then there are lines from Emily Dickinson’s poems which pop up on the screen in handwriting font, reminiscent of other modern shows in which this technique is used to depict text messaging.

THERE IS AN OVERT LINK TO THE PRESENT DAY

Each night the character of Emily Dickinson visits Death, a figure of her Emo imagination, who arrives in a carriage drawn by translucent white horses. In the first episode she gets into the carriage with Death and he gives her some life advice which shows her, and the audience, that he can see into the future. He tells her that in 200 years time she will be the Dickinson everyone remembers. The ‘200 years’ is a clear signal: This version of Emily Dickinson speaks to a modern audience. She was ahead of her time, this says, and she’d have been better off living in the future, with us.

The series becomes less metafictive after the first episode. Having accepted the tone of the show, we are not left to sink fully into the story.

METAHUMOUR

This is subtle, but Emily’s best friend tells Emily during an argument in episode one that she is not lucky like Emily, coming from a well-off background. Her entire family have just died. (This is comically brushed off by Emily’s mother especially — a comment on how death was more normal back then.) Next, Sue says that without marrying Emily’s brother (despite being romantically in love with Emily) she ‘will literally starve’.

This sounds like modern dialogue because the meaning of ‘literally’ has expanded in contemporary English and is used now as a simple intensifier, not as the inverse of ‘figuratively’. At first glance this feels modern, but the (dark) joke is that Sue will indeed starve, because this was the times she lived in.

Anachronistic dialogue works when the audience is encouraged to laugh at it. Perhaps it doesn’t work so well in a story more serious in tone.

DIALOGUE AND CHARACTERISATION

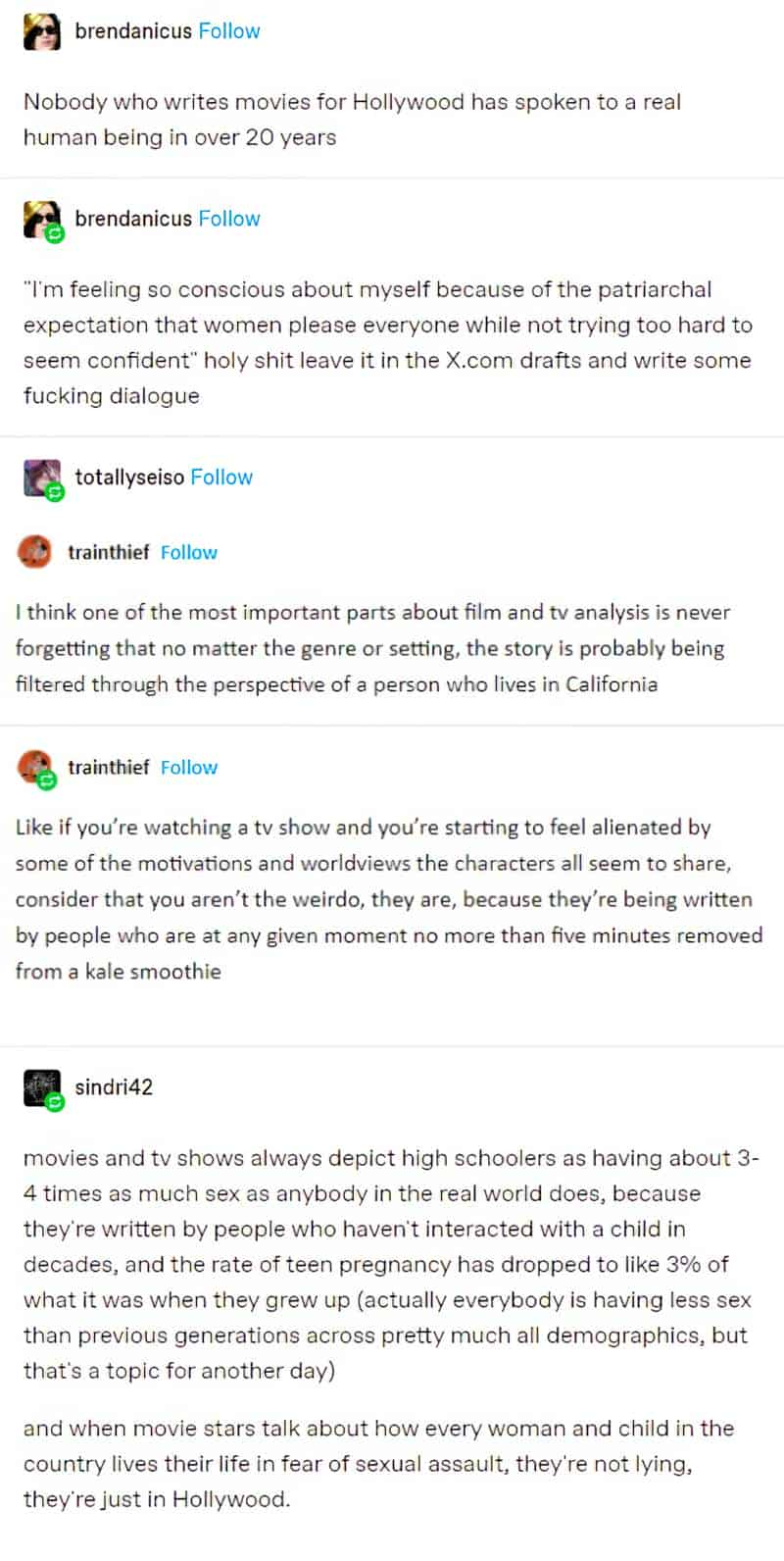

CALIFORNIA DIALOGUE

FURTHER READING

- This nugget of great advice from K.M. Walton

- Dialogue – it’s not just talking from Scott Egan

- How to write effective dialogue in your novel from Bubble Cow

- Rhythm Of The Words: Voice In Dialogue from The Other Side Of The Story

- Dialogue Only Has To Be True To The World Of Your Novel from Nathan Bransford

- 9 Easily Preventable Mistakes Writers Make With Dialogue from The Creative Penn

- 5 Tips For Creating Cheeseless Dialogue from Writers In The Storm blog

- Nods, Smiles, and Frowns: How Can We Avoid “Talking Heads”…and Cliches? from Writers Helping Writers

- Fillers are a necessary part of speech. Here’s a list of fillers from many different languages.